Abstract

The predominant communication disorders post-stroke include aphasia, dysarthria and apraxia of speech. These disorders and their impacts are briefly outlined. The chapter then focuses on the results of an evidence synthesis resulting in 18 evidence-based recommendations for the assessment and treatment of communication disorders acquired after stroke.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Post-stroke aphasia

- Dysarthria

- Rehabilitation

- Behavioural therapy

- Biological therapy

- Evidence base

- Recommendations

1 Introduction: The Clinical Problem

Speech, communication and language disorders are many and heterogeneous. The modalities of communication affected include spoken understanding and expression, reading, writing and gesture. The three predominant speech and language disorders that can be acquired post-stroke are as follows:

1.1 Aphasia

Aphasia is a language disorder affecting understanding of spoken language; the ability to express thoughts verbally, including difficulties with word retrieval (anomia), and sentence production; the ability to read and understand written words and sentences and the ability to write including spelling and structuring written sentences. These difficulties result from damage to the left side of the brain in the majority of people. The extent of impairment to each of the four language domains varies from person to person depending on the locations and extent of neurological damage. Flowers et al. (2013) estimated the incidence of aphasia post-stroke to be 30%.

1.2 Dysarthria

Dysarthria is a motor speech disorder resulting from impaired movement of the muscles used for the production of speech. The main parameters of speech are respiration, phonation, resonance, articulation and prosody. One or more of these parameters can be affected leading to reduced speech intelligibility and reduced communication effectiveness. These parameters can be impaired in different ways (for example muscles may be more or less paretic, become hypotonic or hypertonic), and they may each be impaired to different extents. This results in different dysarthria profiles (e.g. Darley et al. 1975). Flowers et al. (2013) estimated the incidence of dysarthria post-stroke to be 42%.

1.3 Apraxia

Apraxia of speech (AOS), also known as verbal apraxia or dyspraxia, is also a motor speech disorder. AOS results from a reduction in the ability to co-ordinate the gestures required for speech leading to difficulty producing the right sounds in the right order when speaking. It is characterised by multiple different attempts to articulate words accurately. AOS can occur in isolation, but frequently coincides with expressive aphasia. AOS is acquired with lower frequency following stroke than aphasia or dysarthria.

Aphasia, dysarthria and apraxia are not mutually exclusive, and more than one speech and language disorder may need to be treated.

Communication impairments affect everyday activity, for example the ability to have conversations, make phone calls, listen to the radio, write letters, construct emails and text messages and read for pleasure, for information or for work. They may also affect the use of sign language for people in the deaf community. In turn, they restrict participation: the ability to carry out pre-stroke employment, loss of roles within the family and community and withdrawal from participating in usual activities both outside of and within the family. These changes affect the well-being of both the person with a communication disability and their family/carer with increased frustration, misunderstandings and breakdown/strain on relationships. For the carer, increased responsibilities, mending communication breakdowns and misunderstandings, loss of the person to talk to and dealing with frustration of both the person with the communication difficulty and their own have significant impact on their well-being. It is recognised that the impact of a communication impairment is not always proportional to its severity. For example people with relatively mild dysarthria may be intelligible, but sound different thus challenging their identity and self-confidence. Communication disorders also place a burden on society due to increased dependence, loss of employment of both the individual and the carer who may need to give up work to look after the person and reduced ability to perform previous caring roles, looking after other dependent family members for example.

2 Recommendations for the Assessment and Treatment of Post-Stroke Communication Disorders

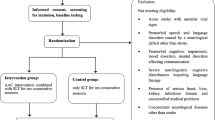

Recommendations have been based on evidence from Cochrane reviews in aphasia, dysarthria and AOS and supplemented with evidence from other systematic reviews and recent RCTs. The Cochrane library was searched for reviews of aphasia/dysphasia, dysarthria, apraxia of speech/verbal dyspraxia and motor speech. Twelve reviews were returned and five (those referring to stroke) were used to inform the recommendations. Additional systematic and narrative review evidence is drawn upon in each section where useful in providing additional clinical direction. An information specialist performed searches for reviews in Medline published from 2010 to December 2017 including aphasia OR dysphasia AND speech and language therapy OR therapy OR treatment OR assessment AND stroke AND meta-analysis OR review. A second search was performed replacing aphasia/dysphasia with apraxia of speech OR dysarthria. Thirty-two results were returned for aphasia and 86 for apraxia or dysarthria. A third search was performed for recent RCTs from 2015 to December 2017, replacing the terms meta-analysis OR review with RCT returning 46 results. The first author reviewed the abstracts of all returned papers and excluded non stroke, non-systematic method, known Cochrane reviews, non-treatment or assessment studies, non SLT interventions and non RCT design (for RCT search only). Eleven reviews for aphasia, two reviews for dysarthria and apraxia of speech and eight recent RCTs were identified. Information from selected reviews and RCTs was used if it added information to that already identified in Cochrane reviews. An additional known review of dysarthria treatment was included, published in 2009. Evidence from adequately powered RCTs published between December 2017 and publication of this chapter have also been added.

Levels of evidence for recommendations are indicated using CEMB (levels 1a to 5 according to the ‘Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine—Levels of Evidence’, last version from March 2009, http://www.cebm.net/Oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine).

The quality of evidence was rated with four categories according to ‘GRADE’ (‘Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation’) (Owens et al. 2010):

-

High quality: further research is unlikely to affect our confidence in the estimation of the (therapeutic) effect.

-

Medium quality: further research is likely to affect our confidence in the estimation of the (therapeutic) effect and may alter the estimate.

-

Low quality: further research will most likely influence our confidence in the estimation of the (therapeutic) effect and will probably change the estimate.

-

Very low quality: any estimation of the (therapy) effect or prognosis is very uncertain.

The grading of the recommendations according to GRADE (Schünemann et al. 2013) corresponds to the categories ‘ought to’ (A) (strong recommendation), ‘should’ (B) (weak recommendation). As a third category had been introduced ‘can’ (0) (option) (Platz 2017). Recommendation category A is granted for clinically effective interventions with high-quality evidence support; with medium-quality evidence category B and with low- or very low-quality evidence category 0 can be appropriate; deviations might be indicated based on clinical judgement, individually applying reasons are denoted in [brackets]. A+ and B+ denote a strong or weak recommendation in favour on an intervention, A− and B− against its use.

2.1 Clinical Assessment of Communication Disorders

With increasing globalisation, the proportion of people who speak more than one language is rapidly expanding with each language potentially being differently affected (Lekoubou et al. 2015). The clinical profile of aphasia may differ to a variable extent, in the two or more languages used by an individual. Aphasia needs to be assessed in all languages spoken by an individual to assist therapeutic planning.

A systematic review by Hachioui et al. (2017) identified screening tests that have been validated for aphasia, with varying methodological quality and levels of bias. These include the Frenchay Aphasia Screening Test (FAST) (Enderby et al. 1987), Language Screening Test (LAST) (Flamand-Roze et al. 2011), Mississippi Aphasia Screening Test (MAST) (Nakase-Thompson et al. 2005), the Mobile Aphasia Screening Test (also MAST) (Choi et al. 2015), ScreeLing (Doesborgh et al. 2003), Sheffield Screening Test for Acquired Language Disorders (SST) (Al-Khawaja et al. 1996), Semantic Verbal Fluency (SVF) (Kim et al. 2011) and Ullevaal Aphasia Screening Test (UAS) (Thommessen et al. 1999).

Recommendation: Screening tests should be used to identify the presence of aphasia (evidence level 2a, very low quality, B+ (clinical importance)).

No validated screening tools have been published for dysarthria or dyspraxia.

The World Health Organisation endorsed the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF) in 2001, recommending assessment of a patient’s impairment, activity and participation. For communication, impairment refers to the speech or language disorder itself and the profile of this. Activity refers to having a conversation, reading and writing. Participation refers to carrying out daily activities that are usual for the individual and the degree to which these have been affected by the communication disorder. Additionally, the ICF encourages assessment of the environment (or context) in which the disability is experienced. The quality of life of both patients and their carers/family members is also an important focus of assessment. Detailed assessment should therefore address all areas identified by the ICF.

Commonly used assessments of impairment that have been validated or shown to be reliable include the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB), Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE-2) and the Comprehensive Aphasia Test (CAT), Aachen Aphasia Test (AAT), Minnesota Aphasia Test (MAT), Porch Index of Communication Ability (PICA) and the Frenchay Dysarthria Assessment (FDA-2).

Recommendation: Published assessments of speech and language should be used to provide a profile of the speech or language disorder in patients with a positive screening result (evidence level 2b, very low quality, B+ (clinical importance)).

A systematic review by van Dijk et al. (2016) reviewed instruments available for assessing depressive symptoms in people with aphasia. The majority were not sufficiently investigated and those that were generally had low methodological quality. However, the authors recommended the Stroke Aphasia Depression Questionnaire–10, the Stroke Aphasia Depression Questionnaire–H10 and the Signs of Depression Scale as most feasible for use in clinical practice.

Recommendation: Published assessments of depression in aphasia can be considered (level of evidence 2a, very low quality, 0).

Goal setting can help with therapy planning. This is usefully conducted with the person with communication difficulties and their families. Goals can be informed by a screening or detailed assessment in combination with what the patient and family wish to achieve from rehabilitation.

There is a rich literature about imaging in aphasia, including predicting outcome and suggesting individual therapy (Faroqi Shah et al. 2013). For the time being, however, imaging techniques still need to be considered research tools, and while they have the potential to eventually become relevant for clinical management, they are currently investigational.

2.2 Behavioural Therapy Interventions

Behavioural therapy interventions can focus on the ICF levels of impairment, activity and participation. Impairment-based interventions can be carried out in order to underpin improvements in activity and participation level goals.

2.2.1 Aphasia Therapy

2.2.1.1 Impairment Focus

The Cochrane review of speech and language therapy for aphasia post-stroke (Brady et al. 2016) included impairment-based interventions based on cognitive neuroscience/psycholinguistic models. For example semantic therapies focussing on interpretation of meaning to improve semantic processing; phonological therapies aiming to improve the sound structure of language; sentence mapping matching meaning to sentence structure and narrative therapy to provide a macrostructure for sentences and discourse. Many impairment-based therapies focus on improving specific domains of language such as reading, writing, comprehension and expressive language and more targeted approaches like semantic-based treatment.

2.2.1.2 Activity/Participation Focus

Constraint-induced aphasia therapy (CIAT) (Pulvermuller et al. 2001), also known as intensive language action therapy (ILAT), is one example of therapy focusing on the activity of using language. The intervention employs constraint, encouraging patients to only use spoken language to communicate during activities such as making requests from other group members.

Functional therapy specifically targets improvement in communication tasks considered to be useful in day-to-day functioning.

Brady et al. (2016) provide evidence from a meta-analysis of RCTs for the effect of speech and language therapy (SLT). Twenty-seven RCTs (1620 participants) assessed SLT versus no SLT. According to these meta-analyses, SLT resulted in clinically statistically significant weak-to-moderate benefit to patients’ functional communication (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.28, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.06 to 0.49, 10 trials, 376 participants), reading (SMD: 0.29 (0.03 to 0.55); 8 trials, 254 participants), writing (SMD: 0.41 (0.41 to0.67); 8 trials, 253 participants) and expressive language (SMD: 1.28 (0.38 to 2.19); 7 trials, 248 participants). However, there is currently no evidence for one type of therapy being superior to another or of long-term effects of therapy.

Recommendation: Speech and language therapy should be provided to people with aphasia as individually indicated to reduce communication difficulties and enhance functional communication (level of evidence 1a, very low-to-moderate quality, B+).

The activity-based ‘constraint-induced therapy’ has been the subject of several studies enabling meta-analysis of results for this therapy specifically. In the Cochrane review (Brady et al. 2016), five RCTs (160 participants) compared CIAT to other forms of therapy. The comparisons showed no evidence of greater improvement with CIAT than with other types of therapy in functional outcomes (SMD: 0.15 (−0.21 to 0.50); 3 trials, 126 participants) or aphasia severity (SMD: 0.11 (−0.57 to 0.79); 2 trials, 34 participants), although the quality of evidence for these findings was low and very low, respectively. Zhang et al. performed a more recent systematic review of RCTs of CIAT in 2017. Eight RCTs were found but conclusions were similar to the Cochrane review, in that CIAT may be useful for improving chronic post-stroke aphasia although there is no evidence of superiority to other techniques.

Recommendation: Constraint-induced aphasia therapy can be considered for the treatment of people with aphasia, especially when promotion of verbal communication activity is the aim (level of evidence 1a, very low to low quality, 0).

2.2.2 Dysarthria Therapy

In a Cochrane review of interventions for dysarthria due to stroke including five small RCTs with 234 participants (Mitchell et al. 2017), there was a statistically significant effect of therapy at the level of impairment immediately post-therapy when comparing treatment to another intervention, placebo or control (SMD: 0.47 (0.02 to 0.92, 4 trials, 99 participants)) but no evidence of a persistent effect (SMD 0.07, (−0.91 to 1.06); 2 trials, 56 participants). There was no evidence of effect of therapy at the level of activity or participation immediately post-therapy (activity SMD: 0.29 (−0.07 to 0.66); 3 trials, 117 participants) (participation SMD: −0.24 (−0.94 to 0.45); 1 trial, 32 participants) or of persistent effects (activity SMD: 0.18, (0.18 to 0.55); 3 trials, 116 participants) (participation SMD: −0.11 (−0.56 to 0.33); 2 trials, 79 participants).

Recommendation: People with dysarthria should receive rehabilitation to try to improve their speech impairment. (level of evidence 1a, very low to low quality, B+ (clinical relevance)).

A narrative review of non-randomised studies outlines impairment-based techniques that have demonstrated some qualitative benefit in improving the clarity of speech (Palmer and Enderby 2007). These include articulation exercises practising precision in the production of single sounds, words and sentences; modelling correct pronunciation of words and sentences and providing feedback ‘clear’ or ‘unclear’ on repeated attempts; use of visual feedback to increase the use of pitch, loudness and intonation (prosody) and use of the Lee Silverman technique to increase loudness.

At the activity level, compensatory strategies to increase intelligibility through purposeful speech production such as over-articulation or slowing rate of speech can be used. Visual feedback and pacing techniques to slow rate (using a metronome or pointing to the first letter of each word on an alphabet chart) have been described (Palmer and Enderby 2007). Evidence is needed to understand the effectiveness of these therapy options.

Recommendation: Techniques to try and improve clarity of speech described in the literature can be considered (level of evidence 3–4, very low quality, 0).

2.2.3 Apraxia of Speech

The Cochrane review of treatments for apraxia of speech post-stroke found no trials had been conducted (West et al. 2005). In 2015, Ballard et al. conducted a systematic review of studies in AOS and included 26 within-participant experimental designs. The review indicated potential benefit at the level of impairment of articulatory-kinematic and rate-rhythm approaches to treatment, although there is no evidence of effect of AOS interventions on activity and participation.

Kinematic approaches involve motoric practice (repetitive practice of phonemes building in complexity), modelling and repetition (watching listening and speaking with the therapist) and articulatory cuing (involving sound production treatment using minimal pair words and prompt for restructuring oral muscular phonemic targets, e.g. tactile cues for accurate articulation placement (PROMPT). Rate-rhythm approaches use prosodic patterns, e.g. melody, rhythm and stress to improve speech production. In addition, Varley et al. published a small RCT (50 participants) in 2016 and showed single word production benefited from a behavioural speech treatment involving hierarchical exercises from understanding word meanings to imagery of word production to repetition to autonomous word production in words then sentences with the exercises presented on a computer. This was compared to a visuospatial sham treatment.

Recommendation: Behavioural treatment approaches can be used to treat the impairment in AOS (level of evidence 2a, very low quality, 0).

2.3 Biological Therapies

2.3.1 Pharmacological Treatments

A number of drugs have been used to try and improve language recovery after stroke. A Cochrane review of pharmacological treatments (Greener et al. 2001) found 10 RCTs evaluating the effect of six different drugs. There was weak evidence that Piracetam may be effective in the treatment of aphasia (odds ratio: 0.46 (0.3–0.7); 5 trials, 661 participants). Patients who were treated with Piracetam were no more likely (considering statistical significance) than those who took a placebo to experience unwanted effects, including death (odds ratio 1.29, 95% confidence interval for difference 0.9 to 1.7). However, despite not reaching statistical significance, the difference in death rate between groups does give rise to some concerns that there may be an increased risk of death from taking Piracetam. A further review and meta-analysis of Piracetam was conducted by Zhang et al. (2016) showing no overall improvement in aphasia severity but pronounced improvement in written language (SMD: 0.35 (0.04 to 0.66); 7 trials, 261 participants).

Recommendation: On the whole, drugs cannot yet be recommended to augment the effects of behavioural therapy for aphasia. Piracetam can be considered to improve aphasia, notably written language but further investigation of long-term effects and safety are needed (level of evidence 1a, very low quality, 0). Pharmacological licensing issues need to be considered based on regional regulatory affairs.

2.3.2 Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation (NIBS)

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) have been employed in chronic aphasia either to suppress the maladaptive and inhibitory right-hemisphere activity or to stimulate compensatory left-hemispheric peri-lesion areas. Elsner et al. (2015) conducted a Cochrane review and meta-analysis of trials that compared the effect of tDCS to control interventions on correct picture naming and found that tDCS did not enhance picture naming (SMD:0.37 (−0.18 to 0.92); 6 trials, 66 participants). Li et al. (2015) conducted a meta-analysis including four RCTs showing that low-frequency rTMS was beneficial for post-stroke patients in terms of naming (SMD: 0.51 (0.16 to 0.86)) with no adverse effects. In 2016, Shak-Basak et al. conducted a systematic review of between and within-subject studies of rTMS and tDCS and concluded that the magnitude of effect on picture naming was similar: rTMS—SMD: 0.448 (8 trials, 143 participants) and tDCS—SMD: 0.395 (8 studies, 140 participants). However, Al Harbi et al. (2017) identify a range of methodological issues with existing studies and consider evidence to be at the pre-efficacy level with emerging evidence at the efficacy level.

Caution must be exercised as non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) may lower the threshold for epileptic seizures, and individual contraindications need to be taken into account (Lefaucheur et al. 2014).

No systematic reviews of non-invasive brain stimulation have been conducted specifically for dysarthria or AOS.

Recommendation: tDCS or rTMS to enhance verbal production in aphasia can be considered (level of evidence 1a, low quality, 0). Licensing of specific medical devices needs to be considered based on regional regulatory affairs and safety standards ought to be followed (level of evidence 1a, level of evidence high, A+).

2.4 Timing, Intensity, Dose and Duration of Therapy

2.4.1 Timing

In a pilot RCT (N = 59), people with moderate and severe aphasia were recruited from 3 days post-stroke. Those who received daily impairment-based therapy of 45 min per day scored 15.1 more points (P = 0.010) on the aphasia quotient and 11.3 more points (P = 0.004) on the functional communication profile than those receiving usual care therapy (which averaged 10.5 min a week) (Godecke et al. 2012).

Recommendation: Early intensive therapy should be considered for people with moderate-to-severe aphasia immediately post-stroke if the individual can tolerate it (level of evidence 2b, low quality, B (clinical relevance)).

Traditionally, it has been thought that recovery from language can reach a ‘plateau’ which has led to intervention not being offered, if a patient is more than 6 months or a year post-stroke in many places. However, there is evidence to suggest people can improve their communication with therapy in the chronic phase. In a review of 21 RCTs, Allen et al. (2012) found evidence to support the use of computer-based treatments, constraint-induced language therapy, group therapies and training of communication partners more than 6 months post-stroke. Further to this, in a computerised word finding therapy RCT (n = 278), Palmer et al. (2019) found that improvement in word finding was not affected by time post-stroke (up to 36 years in this study).

Recommendation: Therapy should be provided to people with aphasia who still wish to have therapy in the chronic phase post-stroke to improve their communication (level of evidence 1a, very low-to-medium quality, B+ (clinical relevance)).

2.4.2 Intensity, Dose and Duration

In the Cochrane review for aphasia (Brady et al. 2016), functional communication was significantly better in people with aphasia that received therapy at a high intensity, i.e. 4 to 15 h a week (MD: 11.75 (4.09 to 19.40); 2 trials, 84 participants), or over a long duration, i.e. 3 to 22 months (SMD: 0.81 (0.23 to 1.40); 2 trials, 50 participants), compared to those who received therapy at a lower intensity, i.e. 1.5 to 5 h a week, or over a shorter period of time, i.e. 2 weeks to 9 months. However, more people stopped attending these highly intensive treatments (of up to 15 h a week) than those who had a less-intensive schedule. People were often more able to tolerate intensive therapy later post-stroke.

An example of intensive speech and language therapy in the chronic stage post-stroke (>6 months) from a high-quality RCT showed significant statistical and clinical benefit of intensive speech and language therapy compared to waiting list controls in 19 rehabilitation centres in Germany (Breitenstein et al. 2017). The intensive therapy was delivered in clinical settings for 10 h or more per week for at least 3 weeks (minimum dose 30 h) and combined one-to-one speech and language therapy, group therapy with an SLT and self-managed computer therapy or pencil and paper linguistic exercises prescribed by an SLT.

Recommendation: People with aphasia who want to improve their language and communication abilities should be offered intensive therapy of a long duration in both the acute and chronic stages post-stroke, if they can tolerate it (level of evidence 1a, medium quality, B+ (clinical relevance)).

There is no Cochrane or systematic review level evidence for timing, intensity, dose or duration of therapy for motor speech disorders acquired after stroke, but neuroplasticity and motor learning principles would suggest that ‘more is better’ for motor speech as well as aphasia.

2.5 Methods of Therapy Delivery

Speech and language therapy is often delivered by a qualified speech and language therapist in a one-to-one, face-to-face therapy session. However, other methods of delivery exist that may make delivery of therapy more efficient:

2.5.1 Group Therapy

Groups of people with communication disorders can be an advantageous way of providing communication therapy, providing exposure to a range of communication partners. The Cochrane review for aphasia (Brady et al. 2016) concluded that there was no difference in functional outcome (SMD: 0.41 (−0.19 to 1.00); 3 trials, 46 participants) or aphasia severity (SMD: 0.15 (−0.21 to 0.50); 4 trials, 122 participants) between therapy provided in a group or one to one.

2.5.2 Use of Volunteers

The Cochrane review for aphasia (Brady et al. 2016) found little indication of a difference in the effectiveness of therapy facilitated by trained volunteers than therapy delivered by an SLT. The volunteers were trained, had access to therapy materials and were delivering interventions designed and overseen by a qualified speech and language therapist. Volunteers could include family members. In addition, Teasell et al. (2016) found limited evidence that suggests CIAT delivered by trained volunteers may be as effective as delivery by experienced speech and language therapists.

2.5.3 Use of Computers/Telepractice

Computers, tablet computers and smartphones can be used to provide therapy materials for communication practice during a therapy session with either a speech and language therapist or a volunteer or can provide an option for independent or self-managed practice between sessions with a therapist to increase the amount of therapy or to increase the duration of therapy where the amount available from a speech and language therapist is limited. Where internet connections are available, it is often possible for the therapist to monitor the progress of the patient remotely and update therapy exercises. In the Cochrane review of aphasia (Brady et al. 2016), there was no difference shown between therapy delivered on a computer and one-to-one therapy from a speech and language therapist in functional communication (SMD: 0.44 (−0.10 to 0.98); 3 trials, 55 participants). In another systematic review of computerised aphasia therapy, Zheng et al. (2016) conclude that therapy delivered using a computer is more effective than no therapy, and potentially as effective as therapy delivered by a speech and language therapist, although they acknowledge the low quality of the evidence due to including only seven small studies. Marshall et al. (2016) also reported a small quasi-randomised study (n = 20) showing potential benefits of using a virtual reality environment for aphasia therapy.

Recommendation: Individual, one-to-one or group therapy from a qualified SLT, computer-mediated therapy and volunteer-supported therapy can all be considered for the provision of speech and language therapy (level of evidence 1a, very low to low quality, 0).

The recommendation for use of computerised aphasia therapy is augmented by an RCT (n = 278) of daily self-managed word finding practice on a computer at home, tailored by a speech and language therapist and supported by monthly volunteer/speech therapy assistant visits (Palmer et al. 2019). Word finding improvement was 16.2% (95% CI 12.7 to 19.6; p < 0.0001) higher in the computer therapy group than in the usual care group and was 14.4% (10.8 to 18.1) higher than in the attention control group. There were no significant differences between groups in conversational ability however.

Recommendation: Use of self-managed computerised therapy for word finding practice should be considered as a method for delivering repetitive practice to improve word finding ability. However, combination with additional techniques to promote functional use of newly learned vocabulary in conversation need to be considered (level of evidence 1b, medium quality, B+).

2.6 Alternative and Augmentative Communication

Communication aids can be low tech, for example alphabet boards to spell out words, picture charts to point to pictures that indicate wishes or E-tran frames that enable a patient to use eye gaze to communicate. Many high-tech aids and apps are also available using advances in technology. Baxter et al. (2012) reviewed the evidence for high-tech communication aids and concluded that although benefit is reported, existing studies use designs that are at a high risk of bias and that the high level of individual variation in outcome requires a greater understanding of patients who may benefit from high-tech communication aid solutions.

Recommendation: Augmentative and alternative modes of communication can be considered (level of evidence 2a, very low quality, 0).

2.7 Communication Environment

2.7.1 Conversation/Communication Partner Training

Several different approaches to communication partner training exist and training has been provided to usual communication partners, volunteers providing opportunities for conversation and healthcare staff. Systematic reviews (including all study designs) by Simmons-Mackie et al. (2016) conclude there is sufficient evidence that communication partner training can improve partner skill in using strategies to facilitate the communication of people with chronic aphasia, although higher quality randomised trials are needed to strengthen this recommendation.

Recommendation: Communication partner training should be considered to facilitate communication (level of evidence 2a, very low to low quality, B+ (clinical relevance)).

2.8 Psychosocial Interventions to Manage Mood Disorders Secondary to Aphasia

It is recognised that people with aphasia and their carers are at high risk of developing depression (Worrall et al. 2016). A systematic review of rehabilitation interventions to prevent and treat depression in aphasia post-stroke from 45 studies (Baker et al. 2017) suggested that for people without depression, interventions such as goal setting and attainment, psychosocial support and communication partner training may be helpful in preventing depression. People with mild depression may benefit from behavioural therapy, psychosocial support and problem-solving. More research is needed in this area however to make strong recommendations.

Recommendation: A range of techniques to support people with mild symptoms of depression can be considered (level of evidence 2a, very low to low quality, 0). People with moderate-to-severe depression require specialist intervention from mental health services in collaboration with stroke specialists.

3 Top Ten Best Practice Recommendations for Aphasia and Forthcoming Information

In this chapter, the authors discuss the evidence base and recommendations for the assessment and treatment of aphasia, dysarthria and apraxia based on a synthesis of Cochrane reviews, other systematic and narrative reviews of randomised and non-randomised studies, and of definitive RCTs conducted since the Cochrane reviews were published.

The Aphasia United Best Practices Working Group and Advisory Committee developed and published ten best practice recommendations for aphasia that are applicable across multiple countries (Simmons-Mackie et al. 2017). This entailed crafting a set of recommendations drawing from research evidence and stroke guidelines and using a Delphi procedure to obtain consensus on wording from healthcare experts from the United States, Canada, Australia, UK, Ireland, China, Germany, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Korea, Greece, Turkey, Japan, Argentina, Israel, South Africa, Russia and India. This chapter would not be complete without making reference to these rigorously developed, internationally applicable recommendations that consider assessment and treatment in the broader context of aphasia management:

-

1.

All patients with brain damage or brain disease should be screened for communication deficits.

-

2.

People with suspected communication deficits should be assessed by a qualified professional (determined by country); Assessment should extend beyond the use of screening measures to determine the nature, severity and personal consequences of the suspected communication deficit.

-

3.

People with aphasia should receive information regarding aphasia, aetiologies of aphasia (e.g. Stroke) and options for treatment. This applies throughout all stages of healthcare from acute to chronic stages.

-

4.

No one with aphasia should be discharged from services without some means of communicating his or her needs and wishes (e.g. using AAC, supports, trained partners) or a documented plan of how and when this will be achieved.

-

5.

People with aphasia should be offered intensive and individualised aphasia therapy designed to have a meaningful impact on communication and life. This intervention should be designed and delivered under the supervision of a qualified professional.

-

6.

Communication partner training should be provided to improve communication of people with aphasia.

-

7.

Families or caregivers of people with aphasia should be included in the rehabilitation process.

-

8.

Services for people with aphasia should be culturally appropriate and personally relevant.

-

9.

All health and social care providers working with people with aphasia across the continuum of care (i.e. acute care to end of life) should be educated about aphasia and trained to support communication in aphasia.

-

10.

Information intended for use by people with aphasia should be available in aphasia-friendly/communicatively accessible formats.

Further insights into factors affecting success of treatments for aphasia are forthcoming from the RELEASE collaboration meta-analysis of individual patient data from aphasia trials internationally (Brady et al. 2020).

References

Al Harbi M, Armijo-Olivo S, Kim E (2017) Transcranial direct current stimulation (Tdcs) to improve naming ability in post stroke aphasia: a critical review. Behav Brain Res 322:7–15

Al-Khawaja I, Wade D, Collin C (1996) Bedside screening for aphasia: a comparison of two methods. J Neurol 243:201–204

Allen L, Mehta S, McClure J et al (2012) Therapeutic interventions for aphasia initiated more than six months post stroke: a review of the evidence. Top Stroke Rehabil 19(6):523–535

Baker C, Worrall L, Rose M, Hudson K, Ryan B, O’Byrne L (2017) A systematic review of rehabilitation interventions to prevent and treat depression in post-stroke aphasia. Disabil Rehabil 19:1–23

Ballard K, Wambaugh J, Duffy J et al (2015) Treatment for acquired apraxia of speech: a systematic review of intervention research between 2004 and 2012. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 24(2):316–337

Baxter S, Enderby P, Evans P, Judge S (2012) Barriers and facilitators to the use of high-technology augmentative and alternative communication devices: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Int J Lang Commun Disord 47(2):115–129

Brady M, Kelly H, Godwin J et al (2016) Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (5):CD000425

Brady M, Ali M, VandenBerg K, Williams LJ et al (2020) RELEASE: a protocol for a systematic review based, individual participant data, meta- and network meta-analysis, of complex speech-language therapy interventions for stroke-related aphasia. Aphasiology 34(2):137–157

Breitenstein C, Grewe T, Flöel A et al (2017) Intensive speech and language therapy in patients with chronic aphasia after stroke: a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint, controlled trial in a health-care setting. Lancet 389:1528–1538

Choi Y, Park H, Ahn K et al (2015) A telescreening tool to detect aphasia in patients with stroke. Telemed E Health 21:729–734

Darley F, Aronson A, Brown J (1975) Motor speech disorders. Saunders, Philadeliphia

Doesborgh S, van de Sandt-Koenderman W, Dippel D et al (2003) Linguistic deficits in the acute phase of stroke. J Neurol 250:977–982

Elsner B, Kugler J, Pohl M, Mehrholz J (2015) Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for improving aphasia in patients with aphasia after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (5):CD009760

Enderby P, Wood V, Wade D et al (1987) The Frenchay aphasia screening test: a short, simple test for aphasia appropriate for non-specialists. Int Rehabil Med 8:166–170

Faroqi Shah Y, Kling T, Solomon J, Liu S, Park G, Braun A (2013) Lesion analysis of language production deficits in aphasia. Aphasiology 28:258–277

Flamand-Roze C, Falissard B, Roze E et al (2011) Validation of a new language screening tool for patients with acute stroke: the language screening test (LAST). Stroke 42:1224–1229

Flowers H, Silver F, Fang J et al (2013) The incidence, co-occurrence, and predictors of dysphagia, dysarthria, and aphasia after first-ever acute ischemic stroke. J Commun Disord 46:238–248

Godecke E, Hird K, Lalor E et al (2012) Very early poststroke aphasia therapy: a pilot randomized controlled efficacy trial. Int J Stroke 7(8):635–644

Greener J, Enderby P, Whurr R (2001) Pharmacological treatment for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD000424

Hachioui H, Visch-Brink E, de Lau L et al (2017) Screening tests for aphasia in patients with stroke: a systematic review. J Neurol 246(2):211–220

Kim H, Kim J, Kim D et al (2011) Differentiating between aphasic and non-aphasic stroke patients using semantic verbal fluency measures with administration time of 30 seconds. Eur Neurol 65:113–117

Lefaucheur JP, Andre-Obadia N, Antal A et al (2014) Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Clin Neurophysiol 125:2150–2206

Lekoubou A, Gleichgerrcht E, McGrattan K et al (2015) Aphasia in multilingual individuals: the importance of bedside premorbid language proficiency assessment. eNeurol Sci 1(1):1–2

Li Y, Qu Y, Yuan M et al (2015) Low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for patients with aphasia after stroke: a meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med 47(8):678–681

Marshall J, Booth T, Devane N et al (2016) Evaluating the benefits of aphasia of aphasia intervention delivered in virtual reality: results of a quasi-randomised controlled study. PLoS One 11(8):e0160381

Mitchell C, Bowen A, Tyson S et al (2017) Interventions for dysarthria due to stroke and other adult-acquired, non-progressive brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD002088

Nakase-Thompson R, Manning E, Sherer M et al (2005) Brief assessment of severe language impairments: initial validation of the Mississippi aphasia screening test. Brain Inj 19:685–691

Owens DK, Lohr KN, Atkins D, Treadwell JR, Reston JT, Bass EB, Chang S, Helfand M (2010) AHRQ series paper 5: grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions--agency for healthcare research and quality and the effective health-care program. J Clin Epidemiol 63:513–523

Palmer R, Enderby P (2007) Methods of speech therapy treatment for stable dysarthria: a review. Adv Speech Lang Pathol 9(2):140–153

Palmer R, Dimairo M, Cooper C, Enderby P, Brady M, Bowen A et al (2019) Self-managed, computerised speech and language therapy for patients with chronic aphasia post-stroke compared with usual care or attention control (big CACTUS): a multicentre, single-blinded, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 18(9):821–833

Platz T (2017) Practice guidelines in neurorehabilitation. Neurol Int Open 1:E148–E152

Pulvermuller F, Neininger B, Elbert T et al (2001) Constraint induced therapy of chronic aphasia after stroke. Stroke 32:1621

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A (2013) GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The GRADE Working Group. Updated October 2013. www.guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook

Shak-Basak P, Wurzman R, Purcell J et al (2016) Fields or flows? A comparative meta-analysis of transcranial magnetic and direct current stimulation to treat post stroke aphasia. Restor Neurol Neurosci 34(4):537–558

Simmons-Mackie N, Raymer A, Cherney L (2016) Communication partner training in aphasia: an updated systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 97(12):2202–2221

Simmons-Mackie N, Worrall L, Murray L et al (2017) The top ten: best practice recommendations for aphasia. Aphasiology 31(2):131–151

Teasell R, Foley N, Salter K et al (2016) The stroke rehabilitation evidence-based review, 17th edn. Canadian Stroke Network, Ottawa

Thommessen B, Thoresen G, Bautz-Holter E et al (1999) Screening by nurses for aphasia in stroke—the Ullevaal aphasia screening (UAS) test. Disabil Rehabil 21:110–115

van Dijk MJ, de Man-van Ginkel JM, Hafsteinsdóttir TB, Schuurmans MJ (2016) Identifying depression post-stroke in patients with aphasia: a systematic review of the reliability, validity and feasibility of available instruments. Clin Rehabil 30(8):795–810. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215515599665

Varley R, Cowell P, Dyson L et al (2016) Self-administered computer therapy for apraxia of speech: two –period randomized control trial with crossover. Stroke 47(3):822–828

West C, Hesketh A, Vail A et al (2005) Interventions for apraxia of speech following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD004298

WHO (2001) International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: ICF. World Health Organization, Geneva

Worrall L, Hoffmann T, Power E, Togher L, Rose M (2016) Reducing the psychosocial impact of aphasia on mood and quality of life in people with aphasia and the impact of caregiving in family members through the aphasia. Trials 17:153

Zhang J, Wei CZ et al (2016) Piracetam for aphasia in post stroke patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. CNS Drugs 30(70):575–587

Zhang J, Yu J, Bao Y et al (2017) Constraint-induced aphasia therapy in post-stroke aphasia rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 12(8):e0183349

Zheng C, Lynch L, Taylor N (2016) Effect of computer therapy in aphasia: a systematic review. Aphasiology 30(2–3):211–244

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Palmer, R., Pauranik, A. (2021). Rehabilitation of Communication Disorders. In: Platz, T. (eds) Clinical Pathways in Stroke Rehabilitation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58505-1_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58505-1_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-58504-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-58505-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)