Abstract

Guatemala is a country particularly susceptible to the effects of climate change. Residents of the country are increasingly experiencing frequent natural hazards, witnessing rising temperatures, and grappling with maintaining sources of income and nutrition. For these and other reasons, it is crucial that Guatemalans have access to effective climate change education in order to be equipped with the skills and knowledge necessary to appropriately adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change in their communities. With Atitlán Multicultural Academy, a K-12 school located in Guatemala’s Western Highlands, as our pilot school, we have created the blueprint for a region-specific guidebook focused on incorporating the spirit of climate action into the areas of leadership, curriculum, community partnerships, and professional development within the school. It is our hope that this guidebook can continually be adjusted and made relevant for schools around the globe as they work to create a culture of shared responsibility for climate action.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

3.1 Introduction

In Chap. 1 of this book, Fernando Reimers explains that climate change education (CCE) is one of the most critical avenues available to prepare individuals to understand the science behind changing climate trends and the impact of human action on the environment, as well as learn strategies for adapting to and mitigating the effects of climate change in their communities. This idea has been emphasized by leaders in international education and climate action, who have proclaimed that “education can bring about a fundamental shift in how we think, act, and discharge our responsibilities toward one another and the planet” (UNESCO 2017, p. 2). In Guatemala, a country particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, the groundwork has been laid for using education to combat these effects, both through the integration of environmental and climate topics into the country’s Basic National Curriculum, as well as through proclamations by the government on the need to make climate change education a national priority. Unfortunately, these efforts have yet to create a culture of climate action and shared responsibility, according to the country’s Minister of Education and its Minister of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN 2017). For this reason, it is essential to identify the gaps that have resulted in this failure. It is only through this examination that solutions can be crafted and implemented in order to meet the goal of creating a culture of shared responsibility and action against climate change in Guatemala.

To that end, this chapter first elaborates on Guatemala’s vulnerabilities to the impacts of climate change and discusses educational efforts currently in place to equip communities with relevant climate adaptation and mitigation skills. Subsequently, it presents an overview of the literature identifying gaps in these efforts and describes an approach within the formal education system which works to address these gaps. More specifically, it will present the blueprint for a region-specific, school-centered guidebook that aims to explain how four particular components of a school’s system can work together towards mitigating and adapting to climate change. The blueprint will also provide examples of the types of activity recommendations included in the guidebook, geared specifically towards helping a pilot school in Guatemala create a schoolwide culture of climate action.

3.2 Impact of Climate Change on Guatemala

As a country, Guatemala faces many concerning challenges, including an immense vulnerability to natural hazards, staggering numbers of people living in poverty, and malnourishment. These challenges will continue to worsen, as the climate continues to change through increased temperatures, extreme rainfall, droughts, floods, and other climate-related changes (USAID 2017). These climate changes pose a particular risk to the people of Guatemala, as they threaten to impact the country’s agricultural sector, an industry which is both reliant on climate conditions and crucial for economic growth and stability. According to the Food and Agriculture (FAO) Policy Decision Analysis, “70 percent of [the country’s] total land area [is] dedicated to agricultural and forestry activities” (FAO 2014, p. 1).

Guatemala has long been vulnerable to climate hazards. According to the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR 2009), it is ranked fifth among countries with the highest economic risk to three or more hazards, particularly due to the vulnerability of its gross domestic product (GDP) to hazards. The GFDRR estimates that about 83.3% of the country’s GDP is located within areas of risk. These areas are vulnerable to both low frequency-high impact events, including earthquakes, volcanoes, and hurricanes, and high frequency-low impact events, such as floods and landslides (GFDRR 2009).

Due to the great levels of inequality within Guatemala, a large part of the population actually lives in places that are not suitable for human habitation. In the Guatemala City metropolitan area, for instance, close to 600,000 people live in landslide-prone hillsides, while an additional 350,000 people live in plains located within flood zones on the Pacific coast and in the departments of Izabal and Petén (Alcarraz et al. 2012). According to the European Commission Humanitarian Aid Department’s Disaster Preparedness Programme, a total of three million people live in high-risk areas within the country (Alcarraz et al. 2012). Making matters worse, these individuals often lack access to basic needs such as water and sanitation, as well as to public services such as education, health, security, and criminal justice. As a result of all these factors, it is in these places that the impact of climate change is the greatest (Hernández 2012).

Additionally, these climate hazards threaten to affect many key areas of individuals’ lives, including children’s schooling. Following the eruption of Volcano Pacaya in 2010, along with the subsequent tropical storm Agatha which brought tremendous rainfall, Guatemala suffered losses of around 640.3 million quetzales (USD 82.9 million) within the education sector alone, mainly as a result of damages to school buildings and infrastructure (CEPAL 2011). According to estimates from the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL 2011), about 6.9% of students enrolled within the country, which constitutes around 229,940 students, as well as 7810 teachers, were affected by these events.

Clearly, climate change poses a considerable risk to Guatemalans and, therefore, a great need exists for communities to become better informed about the impacts of climate change and better equipped with the skills to effectively mitigate these impacts. In 2017, the Guatemalan government stated that “education is one of the pillars of development of communities, with environmental education being particularly essential for the construction of sustainable and resilient societies, committed to the care, protection, and betterment of the environment” (MARN 2017, p. 16). In fact, the government has successfully integrated sustainable development and climate change topics in the Basic National Curriculum (MARN 2017). As a result, environmental education has become a permanent fixture in the national education system, and a commitment to adapting to and fighting against climate change using education as a vehicle for change has been established (CALAS 2010, Congress of Guatemala 2013).

Yet, despite the elevation of this topic to the policy agenda of the national government, the government has acknowledged that these efforts have been insufficient and have largely failed to create a culture of shared responsibility and climate action within society (MARN 2017). In a joint letter published within the 2017 Guatemalan National Policy on Environmental Education, the Ministers of Education and of Environment and Natural Resources stated that “every day, the population is more exposed to… the impact of climate change, a consequence of a social, economic and political system that fails to take into account our shared responsibility for the care and betterment of the environment” (MARN 2017, p. 7). The two ministries have also condemned society’s inaction and particularly its lack of attention to the ways in which climate change is affecting the country’s most marginalized groups (MARN 2017).

Building on the ministers’ claims, we investigated the types of CCE programs currently being carried out within the country and found that the ministers’ concerns are indeed reflected in large part within the Guatemalan education system. On one hand, the severe lack of CCE programming directed towards the country’s most vulnerable populations, including Indigenous groups and its very large out-of-school population, evidences an indifference towards the experiences of those who have the most to lose from the country’s inaction on climate change. Similarly, the overall lack of interdisciplinarity within the Basic National Curriculum, and of teacher professional development opportunities geared towards building competencies on environmental and climate topics, indicate a lack of acknowledgement among the country’s educational authorities about the complex and interdisciplinary nature of this issue. The following section expands upon the gaps that have contributed to the inadequate sense of a climate action-oriented culture and to propose potential solutions to addressing these gaps.

3.3 The State of Climate Change Education in Guatemala and Opportunities for Improvement

There is currently ample will within Guatemala to find ways to leverage education as a means of empowering communities to protect themselves against the effects of climate change. The inclusion of CCE topics into the Basic National Curriculum, particularly, has made an understanding of climate change and its mitigation a priority and has created a space within which additional CCE efforts can be tested and implemented. The following section further explores the reasons why, despite this, a culture of shared responsibility and climate action has yet to be achieved. In particular, it presents a review of literature identifying gaps and failings in Guatemala’s current CCE efforts and then presents what we believe to be the most appropriate solution for creating this culture of climate action within Guatemalan communities. Ultimately, we deemed the whole-school model to be the optimal approach for reaching this goal, given the scope of our project and our overall goal. In the sections that follow we hope that the reasons for our choice to move forward with the whole-school model will be made evident.

3.4 What Are the Major Gaps in Climate Change Education in Guatemala?

There are multiple sources of fragility in equipping the Guatemalan population with the knowledge and skills necessary to mitigate the impact of climate change. These include the lack of bilingual education and of adequate opportunities to educate the large Maya population, the considerable proportion of youth and adults who are out of school and who have achieved very limited formal education, and the lack of coherence and alignment among various components of the education system and a climate change curriculum.

3.4.1 Lack of Adequate Bilingual Education

One of the main concerns expressed by the Guatemalan administration about CCE was the lack of focus on the experiences of underrepresented and underprivileged groups in Guatemala. Indeed, the literature (Patrinos and Velez 2009; de la Garza 2016) confirms that the marginalization of these groups through inequalities within the education system continues to be an enormous challenge for the sector as a whole. One group of particular concern is the large number of students in the country’s Indigenous schools, which experience the highest illiteracy rates in the country and generally perform the worst in key achievement indicators (Patrinos and Velez 2009). A 2009 study published by the Center for Economic and Social Rights for instance, revealed that literacy rates for rural, Indigenous young adults were at around 76%, compared to 96% for urban, non-Indigenous youth (2009). These data illustrate the clear necessity for institutions to devote significant resources to creating programs and policies aimed at meeting this population’s needs for environmental and climate change education.

A 2016 study by de la Garza on the effectiveness of pedagogical mentorship programs in rural and Indigenous schools found that in these schools,

multiple cultural and structural impediments, such as inadequate teacher training on [bilingual intercultural education]… [and] viewing Indigenous languages as a problem… prevented linguistically and culturally relevant education from being enforced… (de la Garza 2016, p. 54)

The lack of relevant bilingual educational offerings is potentially the biggest area of concern when it comes to expanding access to climate change content for Indigenous populations, as even teachers who attend Bilingual Normal Schools for their pre-service teacher education report feeling mostly unprepared to teach the subjects within the Basic National Curriculum (de la Garza 2016). Since many Indigenous communities are located in parts of the country that are immensely susceptible to climate risks and this population is likely to be among the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, it is essential to consider the issue of inadequate bilingual education when considering interventions to creating resilient, climate action-oriented communities.

3.4.2 Out-of-School Youth

A second gap identified in reviewing Guatemala’s existing climate change education efforts is the country’s large, out-of-school youth population and the limited access this population has to information on climate change. In order to understand this challenge in context, it is important to note that the Guatemalan constitution, enacted in 1985, guarantees freedom of education and establishes the obligation of the State “to provide and facilitate education to its inhabitants” (Congreso de la República, 1985, p. 25). More specifically, Guatemalans have “the right and the obligation to receive [free] initial, pre-primary, primary, and basic education within the age limits established by the law” (Congreso de la República 1985, p. 26).

In the more than three decades since the establishment of free basic education in Guatemala, the average length of schooling for youth in the country is still extremely low, at 6.5 years (UNDP 2018). According to USAID (2018), there are currently 1.7 million out-of-school youth, aged 15–24, in the country, many of whom failed to complete a primary education and have limited options for entering the workforce. More than 660,000 of these young people are located in the country’s Western Highlands, a majority-Indigenous region where 60% of the population lives in poverty and which is among the world’s most vulnerable areas to climate impacts (Rainforest Alliance 2017).

Within the aforementioned National Policy on Environmental Education, the government acknowledged that this is yet another societal issue the country has yet to address in its efforts to promote environmental education (MARN 2017). Despite this acknowledgment, there is very little evidence to suggest that it has focused any effort on targeting this population for provision of CCE. Instead, the evidence suggests that the government’s efforts have largely been focused within the country’s formal education system and specifically on reforming the national curriculum to include these topics. Based on this lack of information regarding efforts targeting out-of-school youth, and based on the fact that a large portion of this population is largely Indigenous and lives in some of the world’s most vulnerable regions, we believe that there is yet more reason to be concerned about the equitable distribution of CCE in Guatemala.

3.4.3 Lack of Coherence and Alignment Between Different Components of the School System and Climate Change Education

A last major gap identified in Guatemala’s CCE efforts is the lack of interdisciplinarity in curriculum content on the topic, as well as a general lack of cohesion between this curriculum and other components of school systems. As previously discussed, the Guatemalan Ministry of Education has made the incorporation of climate themes into the country’s Basic National Curriculum a priority. However, a detailed review of this curriculum reveals that climate change-related competencies are only targeted within its natural sciences section, despite research on education for sustainable development that stresses the need for an interdisciplinary approach to these topics (Ministerio de Educación 2007; Annan-Diab and Molinari 2017). Multifaceted issues such as climate change, Annan-Diab and Molinari argue, “require knowledge and skills from distinct disciplines in an integrated manner. Interdisciplinarity promotes the ability to understand complex problems and act on them.” (Annan-Diab and Molinari 2017, p. 11).

Emphasis on climate change topics and the need for this type of interdisciplinary approach is also largely missing from other aspects of the education system, including its teacher professional development structure. Despite advocating for a vision of education that “promote[s] and develop[s] the ideals for a sustainable Earth: a world that is just, with equity and peace, in which individuals take care of the environment to contribute to achieving intergenerational equity,” (Universidad de San Carlos Guatemala 2009, p. 5) the national in-service teacher training program, run through the University of San Carlos, has largely failed to reflect this vision. The training program reflects the same lack of interdisciplinarity towards environmental topics that is present in the Basic National Curriculum, with these topics only being mentioned within the natural sciences portion of the teacher preparation plan. Further, the plan includes no mention of preparation for teachers in topics specifically related to climate change, global warming, or related subjects (Universidad de San Carlos Guatemala 2009).

Despite these concerns regarding the content of the teacher professional development program, an even bigger concern may be the number of teachers the program is actually reaching. A 2011 study found that, when given the same assessment as their students, teachers in sample schools in Guatemala were unable to answer 80% of questions related to the topics they were expected to teach their students (Rojas 2011). In a separate survey, only 18% of teachers in the Western Highlands of the country reported having received in-service training on curriculum topics (Rubio et al. 2017). While the Ministry of Education has dedicated special efforts to incorporating climate change into the curriculum, it has failed to not only acknowledge its complex and interdisciplinary nature, but also to reinforce other components of its education system in an effort to ensure that these curriculum efforts can be effective.

3.5 Moving Forward with a Solution

In light of the multipronged nature of the causes of the limited extent of climate change education in Guatemala, we considered several options to address these deficiencies. In order to address the lack of bilingual education, we explored the possibility of creating early literacy Indigenous language instruction materials focused on environmental themes. Similar to Bazin and Saintis in Chap. 4 of this book, we also recognize the great need to educate out-of-school populations in Guatemala and thus also considered creating a leadership development program focused on the theme of leadership for climate action. Finally, in an effort to remedy the lack of cohesion and interdisciplinarity towards climate topics in the school system, we investigated developing a guidebook utilizing a whole-school approach to creating a culture of climate action within schools.

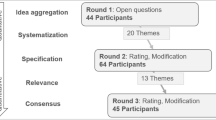

After considering each of these three alternatives and evaluating these different programs ideas using criteria such as efficiency, equity, sustainability, and feasibility, we concluded that working within the formal education system and using a whole-school approach to climate change education was the most promising option to create a culture within communities of shared responsibility towards the environment and action towards mitigating the effects of climate change. While we discovered glaring gaps in the provision of climate change educational topics to certain groups, including Indigenous communities and out-of-school youth, our criteria indicate that the most realistic and feasible problem for us to address at this time is the lack of interdisciplinarity and cohesion between different school elements in the provision of these topics in formal school settings. Additionally, we feel that while programs targeted towards marginalized groups address important symptoms of the problem we have identified, the whole-school approach more directly targets the root cause of the problem, which is the lack of a culture of shared responsibility towards the environment and fellow citizens in Guatemalan society.

Ultimately, our hope is that by presenting schools with a focused resource to guide them in incorporating the idea of climate action into different components of school life, these different components will continually reinforce and strengthen each other in a way that will ultimately create a culture of climate action within the school environment and subsequently, in individual communities and in the country as a whole. As school leadership focuses on sustainable practices and improving the school culture, for instance, teachers are supported to incorporate such lessons into their own teaching, using innovative and impactful practices, all while students are encouraged to learn these topics through project-based learning and by engaging in relevant climate issues with local organizations. As each of these components work together towards the goal of improving the local environment, students will become engaged and motivated to make change outside of school, and a culture of climate action will emerge.

3.6 Preparing a Whole-School-Centered Guidebook for Schools

Given that the goal of providing schools with a resource to guide them in implementing a whole-school approach will be the most effective in creating a culture of shared responsibility and climate action in Guatemalan communities, how can existing resources and best practices on this kind of approach be incorporated and implemented within a school? In the next section we present a review of UNESCO’s Getting Climate Ready (Gibb 2016) report in an effort to identify its most relevant strategies for the Guatemalan communities and schools our guidebook will target. Concurrently, the section will review additional literature on the global “green school” movement in an attempt to identify and consider additional applicable elements to the whole-school approach not discussed within UNESCO’s report. As these elements are identified, each is then elaborated on using an understanding of current best practices and educational research on its effectiveness. Finally, we present a set of proposed activities for a pilot school in Guatemala to implement, alongside expected outcomes for these activities and their relevance to the overall purpose of our project.

UNESCO’s Getting Climate Ready (Gibb 2016) report draws upon extensive research on the effectiveness of adaptable models of school organization in Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), as well as on work being done by schools around the world to take action against climate change. Specifically, it complements this research by suggesting an array of specific actions schools can take to build climate resilience. The report explains that “the whole-school approach to climate change means that an educational institution includes action for reducing climate change in every aspect of school” (Gibb 2016, p. 3). In an effort to create a culture of sustainability within schools, the report presents general guidelines for school governance, teaching and learning, community partnerships, and facilities and operations. These guidelines include ideas such as ensuring everyone in the school has a role to play, addressing climate change in an array of subject areas, providing opportunities for critical, creative, and future thinking, and enabling students to take action (Gibb 2016).

The feasibility and effectiveness of UNESCO’s approach can first be assessed theoretically through the general lens of research done into both large-scale, system-wide reforms, as well as into smaller-scale approaches to school organization and improvement. On the one hand, the literature on successful system reforms find that similarly to the whole-school perspective, such reforms combine both alignment and coherence, meaning that learning, “is the goal of the various components of the system… [and] that the components reinforce each other in achieving whatever goals the system has set for them” (World Bank Group 2018, p. 13). Likewise, school organization and improvement literature ultimately challenges the role of traditional pedagogies in promoting global sustainability and suggests that instead, more adaptable models of school organization that respond at all levels to new research and social movements are better suited to realizing the Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) vision of creating aware and responsible individuals (Morgen et al. 2019). Notably, it has been found that schools which adopt an interdisciplinary, multidimensional ESD implementation strategy have more supportive organizational structures, are better able to leverage community relations, and are ultimately more effective in translating ESD’s objectives into practical reality (Morgen et al. 2019).

Complementary to these findings are the more practical results that have emerged from schools around the world operating under the umbrella of what some call the “green school,” or “eco school,” movement. These green schools have adopted the kind of whole-school approach advocated for in UNESCO’s guidebook, and “aim to include everyone (students, teachers and the local community)… to motivate students to take on environmental problems and seek resolutions particularly at a local level but also thinking globally…” (Gough et al. 2020b, in press). To that end, schools within these networks focus on developing environmental policies and strategies, providing teacher professional development, involving key stakeholders in sustainability decision-making, and other related actions (Gough et al. 2020a). While measuring the broader impacts of these schools has been difficult, many countries have reported evidence of the development of more sustainable practices, an increase in ESD curricular content, increased student action in influencing government policy, and more (Gough et al. 2020a).

Unfortunately however, little additional information exists on the long-term impact of green schools centered primarily around climate action, especially in developing countries contextually similar to Guatemala. Regardless, short-term evaluations of green schools completed in other developing contexts do provide some hope that a similar approach might be able to take root and have an impact in the country. For instance, a recent evaluation of an Eco-School network in the Small Island Developing Countries (SIDS) of Mauritius, Madagascar, Comoros, and Zanzibar found that such an approach was able to foster positive attitudes towards the schools’ role in equipping individuals to address critical challenges by inspiring changes in teaching methods and emphasizing place-based and problem-based learning. Additionally, evaluators observed physical improvements in the schools’ grounds and in their wider communities, as well as improvements to key student outcomes such as school attendance (Copsey 2020).

In light of this additional research on school organization and the green school movement, we have concluded that while the recommendations included in UNESCO’s report constitute a sound basis for thinking about preparing schools to meet the climate challenges facing their communities, there is a critical need to enhance these guidelines to suit the specific needs and opportunities of Guatemalan schools. Furthermore, in an effort to make this guidebook even more context-specific, our enhanced recommendations, presented in the following sections, will be tailored to a school we have identified in Guatemala’s Western Highlands, Atitlán Multicultural Academy (AMA).

AMA is located in a largely Indigenous community located within the department of Sololá, which in the last few years has suffered the impacts of climate change primarily in the form of excessive rainfall and severe droughts (Asociación Amigos del Lago de Atitlán 2018). The school itself is a “K-12th grade, English-immersion school serving students from all backgrounds representative of the Guatemalan Highlands” (Atitlán Multicultural Academy 2020a), with a population of no more than 100 students and a curriculum that strongly emphasizes project-based learning (Atitlán Multicultural Academy 2020b). Our reasons for selecting AMA as our target school include the region’s elevated vulnerability to climate change, as well as the added feasibility afforded to us by the school’s instructional language, existing curriculum and partnerships, and small student population.

As an additional note before presenting our final recommendations, we want to emphasize the importance of two-way communication in crafting this final product. As authors of these recommendations, we have communicated our thoughts and rationale with AMA and have received valuable feedback from faculty and staff in response, much of which has been incorporated into our suggestions. The success of a program like this can only be possible if the school can communicate what works for them and is encouraged to make adjustments as necessary. Schools work hard to address a multitude of priorities, so it is our hope that the whole-school approach can be integrated into systems and structures that schools already have in place.

Additionally, we want to make clear that this is just the beginning of an iterative process. Again, for a program such as this to be successful, it is crucial that our partnership with the school remain open and ongoing in order to make continued necessary adjustments so that implementation of the following components can be achieved, and to ensure continual support so that the whole-school approach can be sustained. As the school begins to implement various aspects of this model, we acknowledge that further revisions will be necessary and we remain committed to eliciting feedback from the school throughout the process in order to create the optimal approach. With that in mind, the following sections present an early-stage version of the recommendations for establishing a whole-school approach based on feedback from members of the AMA community along with some example accommodations that other schools may also consider in implementing the whole-school approach to climate change education.

3.7 School Leadership

The first major element of a whole-school approach addressed within the UNESCO guidelines is the role of school leadership in creating a school culture of climate action. As Gibb (2016) explains, the kind of culture this approach aims to cultivate is one in which responsibility for achieving a schools’ climate action goals are distributed at all levels and not simply concentrated at the top. This form of equitable, distributed leadership aligns with the argument that the successful promotion of sustainability through education necessitates the involvement and action of people in different positions who embrace the idea of change (Wals and Benavot 2017). Specifically, the idea has been shown to effectively engender a school culture that is conducive to conversations on climate action and sustainability, and supportive of related initiatives (Morgen et al. 2019).

In practice, this type of governance structure has already been implemented in green schools around the world and is actually one of the most critical components of the Foundation for Environmental Education’s (FEE) Eco-Schools framework. Like in UNESCO’s guidelines, the creation of an Eco Committee is the first step in FEE’s program, and aims to be as representative of the whole school as possible. According to FEE, the purpose of these committees is to ensure that the voices of all members of the school community are heard, and to ensure that the other facets of the program are successfully implemented (How FEE EcoCampus Worksn.d.). Reviews of FEE’s specific approach have found that such committees help to address one common concern related to the implementation of school-wide sustainability programs, which is the fact that they are typically introduced by a science teacher and thus become disintegrated from other disciplines in the school (Lysgaard et al. 2015). Involving different disciplines and actors of the school community in a student-led committee and giving them ownership over its initiatives allows schools to tackle this problem (Gough et al. 2020b).

In light of this research, our guidebook incorporates the distributed leadership strategy and largely resembles FEE’s and UNESCO’s frameworks for implementing this key aspect of the whole-school approach. Within this component, the major activity we advocate for is the creation of a Climate Action Committee to coordinate the development and implementation of the school’s climate action plan (Gibb 2016). More specifically, the role of this committee would be to plan for the school’s climate-related projects, collaborate on their execution, and work throughout the year to assess their progress and adjust activities accordingly (Gibb 2016). In terms of actually creating the committee, school leaders must ensure to recruit individuals from both inside and outside the school who might have a stake in its climate activities, including students, teachers, administrators, custodial staff, and local community leaders. Finally, leaders must ensure that the group of individuals participating in this activity are also representative of the diversity in age, gender, race, and socio-economic background of the greater school population (Gibb 2016). Figure 3.1 shows a guidebook recommendation for the first stage of this activity, addressed specifically to school leaders.

In speaking with AMA staff about this proposed activity, it was raised to us that the biggest challenge to its successful implementation at the school would be the time commitment required from all parties involved, particularly from the school director. This notion is particularly concerning given existing research on challenges to the implementation of a whole-school approach in green schools, which finds that “programs can often not succeed or be sustained when there is a lack of ownership of the program by the whole school community, or when the program leaders in the school burn out or leave” (Gough 2020, in press). Therefore, with an understanding that success of the whole school approach and of this activity in achieving their intended outcomes relies primarily on the assumptions that there will be active and sustained interest from all stakeholder groups, and that individuals will have the ability to commit the amount of time necessary to carry it out, we found it important to consider ways to then align our recommendation with structures and activities already in place within this specific school.

One potential accommodation that resulted from these conversations is for AMA to incorporate the idea of a Climate Action Committee into its already existing club program. Within the school, students currently meet for one hour per week, during school hours, in interest-based clubs with other students from different grade levels and a classroom teacher in order to undertake activities related to this interest. Adding the Climate Action Committee as a club option for students to join at AMA will free the school director and teachers from the burden of having to schedule time outside of school hours for the committee to meet. Students, too, will be more likely to participate in the committee and be engaged if it is an activity they were able to opt into and one that does not require them to stay past regular school hours.

Once this club or committee is created, our expected output is the presence of an active Climate Action group in the school, within which leadership and responsibility for the school’s climate goals are distributed in a representative manner, and within which concrete action is being taken towards achieving these goals. The main indicator we propose for determining that this output has been successfully achieved is that the committee has decided what these climate action goals are and within a year of its creation has carried out a predetermined number of activities in the pursuit of these goals. The means of verification for this indicator will come from reports drafted by a designated member of the committee detailing the committee’s activities for the year, including attendance numbers and cost summaries.

If the Climate Action Committee is created as planned and successfully executes its activities, and assuming that attendants to these activities see the value of participating and feel motivated to replicate these actions in their wider community, then this committee will serve towards our larger purpose of creating a community of individuals who understand their responsibility towards the environment and use their skills and knowledge to take action against climate change. Additionally, its successful implementation will be vital in reinforcing the other components of the whole school system. Involving teachers and students in this committee, for instance, should make them feel more invested in participating in the professional development and curriculum aspects of our program.

3.8 Community Partnerships

Another aspect UNESCO identifies as crucial to the whole-school approach is the formation of partnerships between schools and community organizations. Through such partnerships, students are able to both learn about the climate and apply said learning outside of the classroom. These relevant, hands-on learning experiences can help students feel better connected to their communities and can create an experience that is a “more effective and long-lasting form of learning” (Beard and Wilson 2006, p. 1). Research indicates that as a result of these experiences, students may be more likely to take action towards solving real problems their communities are facing (Karpudewan and Khan 2017).

Community partnerships also present potential opportunities for professional development for teachers. For example, Marlow and McLain (2011) found that teachers reported a multitude of benefits when participating in experiential learning experiences within various community settings themselves. Experiential learning for educators can, much like for students, serve as “potentially transformative experiences and provide numerous opportunities to touch teachers in unique and highly personal ways” (Marlow and McLain 2011, p. 9). Such experiences for teachers also help to address any worries about implementing these methods in their classrooms (Girvan et al. 2016). In this case, experiential learning in conjunction with local organizations could potentially increase teacher comfort with incorporating climate-action objectives into their curriculum. As a result, schools observe increased implementation in classrooms (Girvan et al. 2016).

Upon review of whole-school approaches to sustainability worldwide, Henderson and Tilbury reported that “partnerships are key components of program design and implementation and in many cases are seen as critical to the program’s success” (2004, p. 19). These partnerships vary, in that some partnerships exist between a school and government authorities, while other schools may partner with civil sector organizations. Additionally, schools’ motivations for establishing partnerships may differ. Some partnerships may be intended to increase financial support, while other partnerships may serve as vehicles to serve the local community (Henderson and Tilbury 2004). New Zealand’s Enviroschools Program utilizes partnerships with a variety of stakeholders. Through their partnership with the Ministry of Education, for example, Enviroschools are able to “strengthen the capacities of teachers and professionals to work effectively in [environmental education]” (Henderson and Tilbury 2004, p. 21). Partnerships create valuable opportunities for schools committed to mitigating climate change.

A partnership already exists between AMA and local organization, Amigos del Lago. The organization is a non profit association that works to “educate, research and ensure [Lake Atitlán’s] conservation” (Asociación Amigos del Lago de Atitlán 2018). Amigos del Lago has already helped to enhance environmental science lessons at the school through providing hands-on activities, and representatives from the organization have previously assisted with the school science fair as judges. We see that this partnership has the opportunity to expand, and is also an indication of the school’s willingness to partner with other organizations.

With this in mind, our guidebook recommends that schools should partner with various local organizations that share “a common vision” with the school and that prioritize sustainable practices, (Blank et al. 2012). Through these sustained partnerships, an array of hands-on and authentic learning experiences can be offered to students in a manner that “encourage[s] each stakeholder to clearly define its role in meeting specific goals” (Blank et al. 2012, p. 13). Rather than simply suggesting schools “have students learn through experience,” (Gibb 2016, p. 16) we provide information about specific local organizations who provide hands-on learning experiences in and out of the classroom for students throughout Guatemala.

Given AMA’s preexisting relationship with community organizations, recommendations regarding this portion of the whole-school approach was well-received by the staff. In fact, faculty members were in the process of initiating additional partnerships, specifically with organizations that could help make clear the importance of advocacy when it comes to matters of climate change in the region. For schools that may not be located near community organizations such as Amigos del Lago, we suggest they look to local colleges and universities, who may have courses or student-led organizations with climate-oriented missions, just as Lee and Nam suggest in Chap. 6. Yet another option may be to reach out to organizations whose missions may not be directly tied to the environment, but who value sustainable practices, such as markets that use sustainable practices.

For those schools just beginning the process to establish partnerships, a reality exists that challenges may arise during these efforts. For example, as experienced by the Eco-Schools Programme in Kenya, “it takes a long time to build relationships with partners due to different priorities and bureaucracy, thus slowing down effective project implementation” (Otieno et al. 2020, in press). This can be particularly problematic for schools who rely on these partnerships to provide resources associated with other components of the whole-school approach, such as professional development or curriculum materials. Other schools have found the “lack of support for community partnerships and competition between various initiatives within the school” (Gough 2020, in press) to be additional challenges in this realm.

Once schools have initiated a partnership with a local organization, and our assumptions are met, we expect the outcomes of the sustained partnership to include increased student engagement within their communities and improved skills among students in regards to climate action. The partnership serves the organization as well, as working with schools generates increased support for the organization’s work and contributes to their work in combating climate change. Indicators by which schools can evaluate their progress within this aspect of the whole-school approach is the number of community partnerships initiated. Schools should also hold themselves accountable to maintain the partnership through engaging their students with the organization, which can be verified through written agreements between the school and organization. Ideally, within the first year of establishing this whole-school approach to becoming a climate action-oriented school, schools should be able to report at least one community partnership.

In an effort to provide a guidebook that is relevant in the sense that it is context-specific, the community partnerships section profiles local organizations for local schools to reach out to. The organization’s name and information is provided, along with a brief overview of some of the organization’s work and any school programs they have in place. Figure 3.2 provides an example of what a community partnership profile might look like in the guidebook.

If community partnerships are created and sustained in a way that allows students to interact and become engaged with the community, assuming students see the value of the work they are doing, then these community partnerships will contribute to the overall purpose of creating a community that uses their skills and knowledge to combat climate change and understands their shared responsibility to protecting the environment. As previously stated, these partnerships will also aid in advancing the other components of the whole school approach. Community partnerships provide unique opportunities for quality teacher development and infuses environmental lessons into the school’s curriculum in multiple ways.

3.9 Curriculum

Curriculum is another important factor in the creation of a whole-school approach to combating climate change. Namely, UNESCO (2017) suggests that schools identify core competencies their students need in order to work towards sustainable development. Schools are then encouraged to incorporate these competencies into the curriculum as it already exists. These objectives are divided into three domains: cognitive, socio-emotional, and behavioral (UNESCO 2017). Respectively, some competencies outlined in these objectives include: knowledge of how human actions contribute to the promotion or prevention of climate change, collaboration towards fighting climate change, and the evaluation of the effects of actions on the climate (UNESCO 2017).

Oldakowski and Johnson (2018) determined that an integrated curriculum, specifically a curriculum that incorporates matters of climate change into core subjects such as math, “leads to improved learning outcomes in the short-term for all…subjects.” (p. 22), and concluded that content-specific skills supported climate-action skills, and vice versa. Results also indicated that schools with great demographic, socioeconomic, and academic diversity among their student populations “improved at the same and sometimes greater magnitude” than their counterpart schools, when given the opportunity to learn in an integrated setting (Oldakowski and Johnson 2018, p. 22).

This integrated approach to curriculum can be seen modeled in green schools around the world. In Israel, one component the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) and Ministry of Education (MoE) look for when certifying a school as a Green School is an integrated curriculum (Tal 2020). In this way, Green Schools in Israel ensure that “environmental topics and concepts are included in various subjects” (Tal 2020, in press). This approach to curriculum can also be seen in Green Schools located in India. Integrating environmental education into other subject areas aids in “ensuring that adequate time is earmarked for pertinent activities” (Sharma and Kanaujia 2020, in press), while also presenting the content in a relevant way.

Our target school, AMA, acknowledges the importance of thinking in an interdisciplinary manner. Students are encouraged to ask questions in ways that can only be answered by drawing upon knowledge from multiple subject areas. The school also conveys to students that knowledge that spans across subject areas empowers and enables them to make positive change in the world (Atitlán Multicultural Academy 2020a). AMA prioritizes creating opportunities that enable students to construct their own knowledge through the use of a hands-on, project-based curriculum. This approach to teaching and learning, paired with the volunteer opportunities provided to students, creates AMA’s “Whole People, Whole Planet” approach, which aims to foster a “wide and inclusive world view” in students (Atitlán Multicultural Academy 2020a).

Given the research and the way in which AMA values interdisciplinarity, this section of our guidebook provides sample lesson plans which model the integration of climate change matters into content area lessons. The previously mentioned objectives for climate change were used as a guide, along with climate matters of great relevance to Guatemalan communities, in order to unite lessons in climate-action with content-specific work. We additionally encouraged teachers to provide students opportunities to develop and improve the cognitive competencies necessary for sustainable development through the study of local environmental concerns. In this way, teachers may address multiple content area standards, along with major objectives addressing climate action.

In speaking with teachers at AMA, we found that many classrooms were already working to incorporate themes of climate change into content area lessons. However, like many teachers in an array of contexts, the biggest roadblock to carrying out such integrated lessons was the lack of appropriate resources. AMA teachers aim to deliver engaging, relevant, and developmentally appropriate lessons to their students. However, finding resources specific to the region’s climate that are appropriate for the age group is challenging. Therefore, it is very important for the guidebook to include not only sample lessons, but also accompanying materials, such as those presented by Rhodes and Wang in Chap. 2. In fact, we suggest schools working to introduce the whole-school model look to Chap. 2, as well as Japanwala’s work in Chap. 5 for further assistance in the realm of curriculum development.

Gough’s review of the challenges green schools face highlights this challenge. Existing curriculum materials that schools may have access to “often do not support green school programs” (Gough 2020, in press). Schools embarking on the journey to adopting a whole school approach to sustainability should be cautioned that it is often the lack of such resources that lead to burn out (Gough 2020). While this guidebook encourages teachers to integrate climate themes into their lessons as they see fit, it is crucial that schools do not burden their teachers by doing so, leading to “eco-fatigue” (Gough 2020, in press). As schools work towards creating an integrated curriculum as part of their whole-school approach, they should be acutely aware of these challenges.

The curriculum section of the guidebook provides several sample lesson plans. These plans are intended to model the creation of integrated lessons, incorporating subject matter content with climate-action objectives using relevant climate topics. Figure 3.3 provides just a portion of one example lesson plan from the guidebook. Not included in this example is the detailed sequence of activities, which provides teachers step-by-step plans for carrying out such an integrated lesson.

In order to achieve this integration of climate-action skills into the school’s curriculum, several assumptions must be met. Specifically, in order for this integrated curriculum to be effectively carried out in schools, we assume that teachers will be willing to address climate themes in their lessons. There is also an assumption that teachers will feel motivation towards creating and carrying out climate-related lessons. The successful integration of this curriculum also relies on an assumption that students will willingly participate in these types of lessons.

Once climate-action competencies are integrated into the school curriculum, and our assumptions are met, our expected outputs include improved student content knowledge about the climate, increased knowledge about sustainable practices, and a rise in student engagement. We propose that the success of the outcomes be measured by student growth in the area of climate change content knowledge. As a means of verification, we suggest schools use data from pre- and post-tests in order to track student improvement in knowledge about climate change and sustainability.

If schools and teachers have access to climate change related activities and lesson plans, and teachers make use of these resources effectively in their classrooms, assuming students are positively impacted by and engaged with the material, this integrated approach to curriculum will contribute to the overall purpose of the program of increased understanding of responsibility for the environment and use of knowledge and skills to fight the effects of climate change. Moreover, an integrated curriculum will reinforce the other aspects of the whole school system in a way that makes the message of shared responsibility clear. An integrated curriculum, in particular, will support student work with community partners in a meaningful way.

3.10 Teacher Professional Development

One final dimension mentioned within the UNESCO guidelines is that of teaching and learning. The guidelines acknowledge that addressing climate change is complex and involves addressing not simply scientific and environmental issues, but also social, cultural, and political issues (Gibb 2016). For this reason, and as previously discussed in the section on curriculum reform, schools should aim to integrate climate action into all subjects and help students develop critical thinking skills to enable them to address these issues (Gibb 2016). Yet, simply infusing new content into the curriculum will be meaningless without one additional, critical action not discussed in the UNESCO guide: adequately preparing teachers to teach these topics and skills in dynamic ways (Gough 2016; Karrow and DiGiuseppe 2019).

While not a component of UNESCO’s approach, it has generally been shown that the promotion of good teaching methods clearly has a significant impact on student outcomes, and that these methods develop as a result of the acquisition by teachers of specific content knowledge, the promotion of certain ethical values and attitudes, and the development of practical skills under the guidance and supervision of experts (Villegas-Reimers 2003). In regards to environmental education specifically, the importance of reaching teachers through pre-service and in-service environmental education programs has long been understood, with UNESCO itself declaring as early as 1977 the need for teachers “to understand the importance of environmental emphasis in their teaching” (UNESCO 1978, pp. 35–36).

For this reason, schools committed to effectively instituting a whole-school approach on climate action must therefore make an intentional effort to equip teachers with the skills and knowledge necessary to effectively carry out their responsibilities within this model. In fact, many environmentally-minded schools around the world are already stressing the professional development of teachers as an important component of ESD, in order to develop and improve educator competencies around teaching climate change (Henderson and Tilbury 2004; Gough 2016). The Eco-Schools program in Malawi, Uganda, and Tanzania, for instance, leverages partnerships with local education authorities and organizations to deliver intensive training for teachers on the Eco-Schools concept and methodology. A recent evaluation of this program completed by the Danish Outdoor Council found that these activities resulted in an increase of both teachers and students applying new environmental learnings at school and at home, an improvement in teaching techniques, and improved academic performance (Danish Outdoor Council 2017).

Within the context of AMA, teacher professional development takes several different forms. Before the beginning of each school year at AMA, new and returning teachers participate in a two-week teacher preparation period, during which they each create and present their own professional development workshops to the rest of the faculty, receive guest lectures from community leaders on topics pertaining to pedagogy and curriculum content, and are given time to collaborate on curriculum development and lesson planning (personal communication, December 7, 2019). During the school year, teachers are then paired up and encouraged to visit each other’s classrooms and give feedback. While there is certainly room for improvement in terms of continued professional development for teachers throughout the school year, the school has shown a commitment to supporting the improvement of its teachers in a variety of ways (personal communication, December 7, 2019).

Based on both the research supporting teacher professional development in CCE and the supportive culture built around teacher improvement at AMA, we intend for our guidebook to stress the importance of teacher professional development as a component of the whole-school approach. In our attempt to do so, we propose several activities for the school to implement in order to develop all teacher’s competencies in climate change topics, not just science teachers. Our first recommendation is for schools to have teachers regularly participate in in-service training workshops on environmental and climate change education. The topics of these workshops can range from understanding the science behind climate change, to guidance on incorporating climate change topics into non-science subject lesson plans.

In speaking to the staff at AMA, we once again received the feedback that the biggest challenge to the implementation of these workshops will be the time requirement for teachers. Currently, staff meetings are held only once per week for 45 minutes at the school, meaning that any workshops that take place during this time would have to be quite short. The staff agreed that teachers would be reluctant to attend additional workshops outside of this time. For this reason, our guidebook still provides workshop recommendations, but it also stresses additional teacher PD activities that will have the aim of allowing teachers to become active participants in their own development and that of their colleagues without adding to the hours they need to work. An example of how one such recommendation will look is in Fig. 3.4.

As with the previous elements we have discussed, the success of these activities in achieving our preferred outcomes relies on several assumptions we are making about the teachers that will be participating in this professional development. The first big assumption we are making is that teachers will see the value in additional professional development opportunities specifically focused on climate change topics and feel invested in increasing their knowledge on these topics. An additional assumption is that both teachers and the administration will be on board with changes in pedagogy that might result from these opportunities, namely, a shift to more project-based learning activities in the classroom. Finally, one last, large assumption is that once teachers have learned new skills and knowledge related to teaching climate-related topics, they will actually feel comfortable in delivering this content in the classroom.

Once teacher professional development activities are implemented in schools and our assumptions about teacher motivation and comfort are met, our expected outputs include increased teacher content knowledge of climate change and increased incorporation and delivery by teachers of climate change-related topics in lessons in all subject areas. The main indicator we propose for determining whether these outputs have been achieved is that teachers are indeed increasing their delivery of climate-related lessons and are doing so in a competent manner. The primary means of verification for these indicators would be classroom observations and teacher evaluations by the school principal, who would first verify that these lessons are being delivered, and then determine whether it is being done skillfully.

As with the previously discussed components of the whole-school approach, teacher professional development is vital to the eventual achievement of our project’s larger purpose. If the teachers’ content knowledge on climate change increases and they incorporate this knowledge into lessons in the classroom, assuming that students feel more engaged with the material as a result of their teachers’ increased comfort, then this will also serve towards our larger program purpose. Further, increased teacher PD and consequently, increased incorporation of these topics into classroom lessons will also serve to complement the whole school’s other components. Increased teacher content knowledge, for example, will allow teachers to be more engaged and productive members of the distributed leadership structure. Teachers who are members of the Climate Action Committee will be able to make more informed recommendations regarding the committee’s activities and be able to better guide and support the rest of the members in their pursuit of established climate goals.

3.11 Conclusion

Climate change education is increasingly becoming one of the world’s best hopes for preparing individuals to adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change impacting their communities. While the Guatemalan government has acknowledged its importance and made significant progress in incorporating climate change topics into its national curriculum, the country has yet to achieve a culture of shared responsibility and action towards the environment, according to the country’s Ministers of Education and the Environment. One of the primary reasons for this is that the government’s CCE efforts have largely ignored the functioning of schools as systems whose different components constantly interact and reinforce each other. In response to this failing in Guatemala’s CCE efforts, we have created a guidebook, meant to enable schools to create and fulfill their own climate action goals through attention to four key areas of school life: school leadership, community partnerships, curriculum, and teacher professional development. Our ultimate hope is that by incorporating climate action into these different components, they will reinforce and strengthen each other in a way that will ultimately create a culture of climate action within the school environment and subsequently, in individual communities, and in the country as a whole.

References

Alcarraz, I.C., Calderón Moreno, L.E., & Barillas, E.M. (2012, January 23). Documento de Prioridades DIPECHO VII. Retrieved October 2, 2019, from: https://issuu.com/achcentroamerica/docs/documento_de_referencia__17._documento_pais_guate

Annan-Diab, F., & Molinari, C. (2017). Interdisciplinarity: Practical approach to advancing education for sustainability and for the Sustainable Development Goals. The International Journal of Management Education, 15(2, Part B), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2017.03.006.

Asociación Amigos del Lago de Atitlán. (2018, January). Educando Para Conservar—Material de referencia para el desarrollo de la educación ambiental en el departamento de Sololá y la Cuenca del Lago de Atitlán. Retrieved December 13, 2019, from https://amigosatitlan.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/educando-para-conservar-2018-br.pdf

Atitlán Multicultural Academy. (2020a). About Atitlán Multicultural Academy. Retrieved December 13, 2019, from http://www.ama.edu.gt/about-2/

Atitlán Multicultural Academy. (2020b). Curriculum. Retrieved from http://www.ama.edu.gt/curriculum-2/

Beard, C. M., & Wilson, J. P. (2006). Experiential learning: A best practice handbook for educators and trainers. London: Kogan Page.

Blank, M. J., Jacobson, R., & Melaville, A. (2012). Achieving results through community school partnerships: How district and community leaders are building effective, sustainable relationships. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. Retrieved from http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education/report/2012/01/18/10987/achieving-results-through-community-school-partnerships/.

Center for Economic and Social Rights (CESR). (2009). Guatemala: Rights or privileges? Fiscal commitment to the rights to health, education and food in Guatemala. Retrieved October 2, 2019, from http://www.cesr.org/guatemala-rights-or-privileges

Centro de Acción Legal - Ambiental y Social de Guatemala (CALAS). (2010). Decreto Numero 74–96. Retrieved October 2, 2019, from http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/gua60658.pdf

CEPAL. (2011, April). Guatemala: Evaluación De Los Impactos Económicos, Sociales Y Ambientales, Y Estimación De Necesidades A Causa De La Erupción Del Volcán Pacaya Y La Tormenta Tropical Ágatha. Retrieved October 2, 2019, from https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/26047/S2011022_es.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Congreso de la República. (1985). Constitución Política de la República de Guatemala. Retrieved October 2, 2019, from https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Guatemala_1993.pdf?lang=en

Congress of Guatemala. (2013, September 5). Framework law to regulate reduction of vulnerability, mandatory adaptation to the effects of climate change, and the mitigation of greenhouse gas effects (Decree of the Congress 7–2013). Retrieved December 13, 2019, from http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/GUATEMALA.pdf

Copsey, O. (2020). A regional approach to eco-schools in the Western Indian Ocean. In A. Gough, J.C-K. Lee & E.P.K. Tsang (Eds.), Green schools globally: Stories of impact on education for sustainable development. Cham: Springer.

Danish Outdoor Council (2017). Eco-Schools Best practice in Uganda, Tanzania and Malawi. http://www.groentflag.dk/media/1737659/doc_best-practice-study_20-june_print-10.pdf

de la Garza, K. (2016). Pedagogical mentorship as an in-service training resource: Perspectives from teachers in Guatemalan rural and Indigenous schools. Global Education Review, 3(1), 45–65.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (FAO). (2014). Country fact sheet on food and agriculture policy trends—Guatemala 5.

Gibb, N. (2016). Getting climate-ready: A guide for schools on climate action. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000246740.

Girvan, C., Conneely, C., & Tangney, B. (2016). Extending experiential learning in teacher professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 58, 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.04.009.

Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR). (2009). Disaster risk management programs for priority countries. Washington, DC: The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0484-7. Retrieved from https://www.unisdr.org/files/14757_6thCGCountryProgramSummaries1.pdf.

Gonzalez, J. (2016, September 25). How pineapple charts revolutionize professional development. Cult of Pedagogy. https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/pineapple-charts/

Gough, A. (2016). Tensions around the teaching of environmental sustainability in schools. In T. Barkatsas & A. Bertram (Eds.), Global learning in the 21st century (pp. 83–102). Sense Publishers.

Gough, A. (2020). Transforming education through green schools: Trials, tribulations and tensions. In A. Gough, J. C.-K. Lee, & E. P. K. Tsang (Eds.), Green schools globally: Stories of impact on education for sustainable development. Cham: Springer. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783030468194

Gough, A., Lee, J. C.-K., & Tsang, E. P. K. (Eds.). (2020a). Green school globally: Stories of impact on education for sustainable development. Cham: Springer.

Gough, A., Lee, J. C.-K., & Tsang, E. P. K. (2020b). Green school movements: An introduction. In A. Gough, J. C.-K. Lee, & E. P. K. Tsang (Eds.), Green schools globally: Stories of impact on education for sustainable development. Cham: Springer.

Guatemala Sector Brief—Education. (2017, December 1). Retrieved December 13, 2019, from https://www.usaid.gov/guatemala/education

Henderson, K., & Tilbury, D. (2004). Whole-school approaches to sustainability: An international review of sustainable school programs. Report Prepared by the Australian Research Institute in Education for Sustainability (ARIES) for The Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australian Government. Retrieved from http://aries.mq.edu.au/projects/whole_school/files/international_review.pdf

Hernández, A. (2012). Cambio climático en Guatemala. Efectos y consecuencias en la niñez y la adolescencia. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/guatemala/media/1391/file/Cambio%20clim%C3%A1tico%20en%20Guatemala.pdf.

How FEE EcoCampus works. (n.d.). Eco schools. Retrieved April 30, 2020, from https://www.ecoschools.global/how-it-works

Karpudewan, M., & Khan, N. S. M. A. (2017). Experiential-based climate change education: Fostering students’ knowledge and motivation towards the environment. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 26(3), 207–222.

Karrow, D., & DiGiuseppe, M. (Eds.). (2019). Environmental and sustainability education in teacher education: Canadian perspectives (pp. 2–18). Cham: Springer.

Lysgaard, J., Larsen, N. and & Læssøe, J. (2015). Green Flag Eco-Schools and the Challenge of Moving Forward. In V. Thoresen, D. Doyle, J. Klein, & R. Didham (Eds.), Responsible Living (pp.135–150). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15305-6_10.

Marlow, M. P., & McLain, B. (2011). Assessing the impacts of experiential learning on teacher classroom practice. Research in Higher Education Journal, 14, 1–15.

Ministerio de Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. (MARN). (2017, August). Política Nacional De Educación Ambiental De Guatemala. Retrieved October 2, 2019, from http://www.marn.gob.gt/Multimedios/10363.pdf

Ministerio de Educación. (2007). Curriculum Nacional Base Sexto Grado. Retrieved December 9, 2019, from http://www.avivara.org/images/CNB_Sexto_Grado-reduced.pdf

Morgen, A., Gericke, N., & Scherp, H.-Å. (2019). Whole school approaches to education for sustainable development: A model that links to school improvements. Environmental Education Research, 25(4), 508–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2018.1455074.

Oldakowski, R., & Johnson, A. (2018). Combining geography, math, and science to teach climate change and sea level rise. Journal of Geography, 117(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221341.2017.1336249.

Otieno, D., Wandabi, D., & Dixon, L. (2020). Eco-schools Kenya: Practising education for green economy and sustainability. In A. Gough, J. C.-K. Lee, & E. P. K. Tsang (Eds.), Green schools globally: Stories of impact on education for sustainable development. Cham: Springer. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783030468194

Patrinos, H. A., & Velez, E. (2009). Costs and benefits of bilingual education in Guatemala: A partial analysis. International Journal of Educational Development, 29(6), 594–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.02.001.

Rainforest Alliance. (2017, September 12). Getting ahead of climate change in Guatemala’s Western highlands. Retrieved December 12, 2019, from https://www.rainforest-alliance.org/articles/getting-ahead-climate-change-guatemala-western-highlands

Rojas, A. (2011, November 16). Educación afronta graves deficiencias – Prensa Libre. Retrieved December 9, 2019, from https://www.prensalibre.com/guatemala/educacion-afronta-graves-deficiencias_0_592140806-html/

Rubio, F., de Véliz, L. R., Mosquera, M. C. P., & López, V. S. (2017). Impact of teachers’ practices on students’ Reading comprehension growth in Guatemala. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2017(155), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20191.

Sharma, P. K., & Kanaujia, P. R. (2020). Journey of green schools in India. In A. Gough, J. C.-K. Lee, & E. P. K. Tsang (Eds.), Green schools globally: Stories of impact on education for sustainable development. Cham: Springer.

Tal, T. (2020). Green schools in Israel: Multiple rationales and multiple action plans. In A. Gough, J. C.-K. Lee, & E. P. K. Tsang (Eds.), Green schools globally: Stories of impact on education for sustainable development. Cham: Springer. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783030468194.

UNESCO. (1978). Intergovernmental conference on Environmental Education: Tbilisi (USSR) (Final Report). 14–26 October 1977. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2017). Changing minds, not the climate: The role of education. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000266203.locale=en

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2018). Human development indices and indicators: 2018 statistical update. New York: UN. https://doi.org/10.18356/656a3808-en.

Universidad de San Carlos Guatemala. (2009, June). Rediseño curricular Del Programa de Desarrollo Profesional del Recurso Humano del Ministerio de Educación. http://www.mineduc.gob.gt/portal/contenido/banners/profesionalizacionDocente/documents/PADEP_D_curriculo_USAC-EFPEM.pdf

USAID. (2017). Climate change risk profile: Guatemala. Washington, DC: USAID.

Villegas-Reimers, E. (2003). Teacher professional development: An international review of the literature. Paris: International Institute for Educational Planning. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000133010.

Wals, A. E. J., & Benavot, A. (2017). Can we meet the sustainability challenges? The role of education and lifelong learning. European Journal of Education, 52, 404–413. https://doi-org.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/10.1111/ejed.12250.

World Bank Group. (2018). Learning to realize education’s promise. World Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

According to UNESCO (Gibb 2016), the key to a whole school approach to climate action is a commitment to continual improvement. In many ways, this commitment has been reflected in the process of the creation of our guidebook, which has been the result of deep collaboration and continual back-and-forth feedback between the parties involved in its creation. Going forward, this commitment must also be reflected in the implementation of the whole-school approach. This means that schools must be sure to engage in a process of carefully and intentionally planning for, executing, and reflecting on the incorporation of climate action into the four key elements of the whole school (Gibb 2016). Below is a checklist, adapted from one within UNESCO’s guidebook, to help schools ensure they are properly engaging in this process.

Climate Action Checklist – Steps to build a culture of climate action in your school

PLAN |

School Leadership |

⃞ Stakeholder Mapping by School Leadership |

The first key step in the creation of a distributed leadership structure is a thorough mapping of all actors, both internal and external, who may have a stake in the school’s climate action activities. These individuals may include students, teachers, principals, school staff, community members, and others. |

⃞ Creation of a Climate Action Committee or Club |

In the creation of the school Climate Action Committee, school leaders must ensure to recruit individuals from both inside and outside the school who might have a stake in its climate activities, and must ensure that the group of individuals participating in this activity are representative of the diversity in age, gender, race, and socio-economic background of the greater school population. |

⃞ Assessment of school needs in relation to climate action |

Once created, the school Climate Action Committee or Club must collaborate on an honest assessment of the school’s current needs and performance in the area of climate action. This will be critical for setting ambitious, yet realistic and feasible priorities for climate action. |

⃞ Development of a climate action plan for the year |

The school’s climate action plan should outline the school’s priorities and planned activities for the years, state the budget and expected costs for these activities, and lay out their expected outcomes and timelines. |

Community Partnerships |

⃞ Research into local organizations |

The Climate Action Committee will research local organizations who have missions to combat climate change. The committee might look into environmental organizations, small businesses, large corporations, or other organizations nearby. |

Integrated Curriculum |

⃞ Assessment of existing curriculum resources and needs |

School leadership and the Climate Action Committee will create and administer surveys to all teachers to gather information regarding the existing climate-related resources in the school, as well as the needed resources for incorporating climate-themes into the curriculum. |

⃞ Conversation with implementing partner regarding outside research and resources |

After identifying the resources needed, the committee will share these findings with partners and other stakeholders. |

Teacher Professional Development |

⃞ Assessment of teacher needs, time availability, and existing PD resources |

School leadership will assess teacher competencies in climate topics, and administer surveys to all teachers to gather information regarding their needs, interests, and time availability for professional development on the topic. |

⃞ Conversation with implementing partner regarding outside research and resources |

In addition to sourcing recommendations and ideas regarding curriculum integration for local organizations, school leadership should also engage in an assessment of partner capacity to provide resources and assist in teacher PD. |

ACT |

School Leadership |

⃞ Execution of planned activities for the year |