Abstract

Trade and access to international capital markets are often assumed to support countries’ development, notably through technology transfers that support convergence. In this chapter we review economic developments in the EU Central, Eastern and Southeastern (CESEE) countries (namely Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia and Slovakia) since the late 1990s, linking their take-off to the opening to trade and infusion of foreign direct investment (FDI), largely facilitated by the EU accession and geographical proximity. The region has had one of the most significant growth of foreign investment as a share of GDP in the recent global history, and this has contributed to productivity convergence. We argue that FDI increased the well-being of people, by bringing in new jobs and higher wages, led to technological spillovers to domestic firms and increased efficiency and innovation in the market. Various trade-offs, particularly regarding the political implications of privatising national resources, repatriating profits and agglomeration effects are also acknowledged. We conclude that FDI can act as a force of growth and convergence when it comes alongside with a strong institutional, legal and regulatory environment, on the likes of the EU Single Market.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Poland and Hungary were the first countries to sign the Association Agreements in 1994. Croatia signed it in 2005.

- 2.

At various times in the 1990s, inflation in Romania or Bulgaria reached more than 300% but Slovenia, Poland or Czechia also witnessed rates of 30% to 50% in the early 1990s.

- 3.

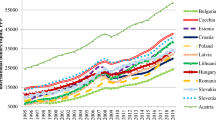

See Annex A with some basic charts. The Baltics are Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania; Visegrád is the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland and Hungary; the South is Bulgaria, Romania, Slovenia and Croatia.

- 4.

For consistency with UN data, we use US Dollars when comparing the CESEE countries with the rest of the world. We use euro when comparing the countries at the EU level.

- 5.

Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Georgia, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Ukraine.

- 6.

The Netherlands appears often among top investors because of their intermediate role: many investment projects are channelled via special purpose vehicles and entities for fiscal and regulatory reasons (see, e.g. Weyzig 2013).

- 7.

An SPE is legal entity with no or few non-financial assets and employees, little or no production or operations and sometimes no physical presence beyond a ‘brass plate’ confirming its place of registration. Half of EU’s FDI is channelled via SPEs, particularly in Netherlands, Luxembourg and Malta.

- 8.

Figures for Bulgarian regions only include non-financial FDI.

- 9.

However, some of the data may be misleading. A case in point is Estonia where outward FDI in the financial sector is driven by local branches of Swedish banks operating in the region (see, e.g. Durán 2019).

- 10.

Due to data availability, all data in this section include FDI generated via SPEs.

- 11.

Lithuania has higher productivity levels, but the car manufacturing sector is very small in the country.

- 12.

- 13.

This is, of course, not mechanical. Borenszteina et al. (1998) explore the conditions under which FDI increases productivity more than domestic investment. Not surprisingly, the formation of human capital turns out to be a critical factor.

- 14.

See Chiacchio et al. (2018) for the effect of FDI on the absorptive capacity of frontier firms and the trickle-down effect on laggards.

- 15.

For a more nuanced view on FDI in general, see Mencinger (2003) and references therein.

- 16.

In general, foreign firms often perform better in terms of capital, labour and corporate governance.

- 17.

In this regard, the EU has recently adopted a new EU framework for the screening of FDI in order to better scrutinise purchases by foreign companies that target Europe’s strategic assets. The area remains a national competency but it will enhance cooperation among member states on these matters.

- 18.

Contessi et al. (2013) note that FDI inflows are countercyclical in developing countries, most likely because of the low price of local firms for potential foreign owners during recessions, particularly during large devaluations or depreciations of the local currency.

- 19.

Javorcik and Poelhekke (2017) show for a sample of Indonesian firms that disinvestment is associated with a drop in total factor productivity, output, mark-ups and export and import intensities.

References

Borensztein, E., De Gregorio, J., & Leec, J.-W. (1998). How Does Foreign Direct Investment Affect Economic Growth? Journal of International Economics, 45 (1), 115–135.

Brada, J., & Tomšík, V. (2009). The Foreign Direct Investment Financial Life Cycle: Evidence of Macroeconomic Effects from Transition Economies. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 45(3), 5–20.

Canton, E., & Solera, I. (2016). Greenfield Foreign Direct Investment and Structural Reforms in Europe: What Factors Determine Investments? European Commission, European Economy Discussion Paper 33.

Chiacchio, F., Gamberoni, E., Gradeva, K., & Lopez-García, P. (2018). The Post-Crisis TFP Growth Slowdown in CEE Countries: Exploring the Role of Global Value Chains (European Central Bank Working Paper No. 2143).

Contessi, S., De Pace, P., & Francis, J. L. (2013). The Cyclical Properties of Disaggregated Capital Flows. Journal of International Money and Finance, 32, 528–555.

Durán, J. (2019). FDI and Investment Uncertainty in the Baltics. European Commission Economic Brief No. 043, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Parliament. (2016). Cost of Non-Schengen: The Impact of Border Controls Within Schengen on the Single Market. European Parliament: European Parliamentary Research Service.

Hansen, H., & Rand, J. (2006). On the Causal Links Between FDI and Growth in Developing Countries. The World Economy, 29(1), 21–41.

Javorcik, B. S., & Poelhekke, S. (2017). Former Foreign Affiliates: Cast Out and Outperformed? Journal of the European Economic Association, 15(3), 501–539.

Keller, W. (2004). International Technology Diffusion. Journal of Economic Literature, 42(3), 752–782.

Mencinger, J. (2003). Does Foreign Direct Investment Always Enhance Economic Growth? Kyklos, 56(4), 491–508.

Szabo, S. (2019). FDI in the Czech Republic: A Visegrád Comparison, European Commission Economic Brief. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Weyzig, F. (2013). International Finance and Tax Avoidance Via Dutch Special Purpose Entities. Paper for Presentation at Research Seminar, Radboud University Nijmegen.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this chapter are those of the authors and should not be attributed in any way to the European Commission. We thank Jolita Adamonis, Judita Cuculic Zupa, Natalie Lubenets, Janis Malzubris, Ana Xavier, István P. Székely and others for many discussions, comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Annex A: Some Basic Figures

Trade and investment in CEE countries. (a) Real exports per capita, (b) share of intra-EU exports, (c) investment rate, excluding dwellings, (d) balance of FDI flows. Notes: (i) The Baltics are Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania; Visegrád countries are Czechia, Slovakia, Poland and Hungary; the South is Bulgaria, Romania, Slovenia and Croatia. (Source: Own calculations based on the AMECO database and UNCTAD)

Annex B: Some Tables with Detailed Data

Annex C: Value Added, Productivity and FDI in NUTS3 Regions

Code | NUTS 2 region | Significant city | Top employment sector | Change of GDP vs EU 2007–2016 | GVA/h | Wages and salaries per number of employees | Largest foreign investor | FDI stock (mil. EUR) | GDP (mil. EUR) | FDI stock/GDP (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1st sector | 2nd sector | Industry | Construction | Wholesale, retail, transport, hotels & rest | ITC | Controlling group | From | Rank Coface500 | ||||||||

BG31 | Northwestern | Pleven | Textiles | Food | 2.4 | 15.3 | 2982 | 2714 | 1851 | N/A | Great Wall Motors | CN | N/A | 521 | 3486 | 15 |

BG32 | Northern Central | Ruse | Textiles | Food | 5.0 | 15.3 | 3818 | 1976 | 2614 | 2923 | HSE | SI | N/A | 1023 | 4017 | 25 |

BG33 | Northeastern | Varna | Food | Textiles | 4.3 | 16.7 | 4495 | 3269 | 2563 | 5000 | Energo Pro | CZ | N/A | 2568 | 5457 | 47 |

BG34 | Southeastern | Burgas | Food | Metals | 9.8 | 17.2 | 5419 | 3333 | 2582 | 2339 | Lukoil | RU | 35 | 2983 | 6685 | 45 |

BG41 | Southwestern | Sofia | Textiles | Food | 11.5 | 26.0 | 5958 | 4638 | 5902 | 14,901 | Aurubis | DE | 43 | 14,496 | 24,742 | 59 |

BG42 | Southern Central | Plovdiv | Textiles | Food | 4.9 | 14.8 | 4023 | 1789 | 2409 | 5411 | Molson Coors | US | N/A | 2842 | 7258 | 39 |

CZ01 | Prague | Prague | Wood | Metals | 2.7 | 67.5 | 16,909 | 10,532 | 18,169 | 27,208 | Alpiq | CH | 11 | 80,185 | 48,751 | 164 |

CZ02 | Central Bohemia | Mlada Boeslav | Motor | Metals | 2.8 | 47.3 | 11,461 | 3842 | 6525 | 2344 | VW | DE | 2 | 10,306 | 22,784 | 45 |

CZ03 | Southwest | Plzeň | Metals | Motor | 4.0 | 42.8 | 9261 | 5746 | 6298 | 7968 | Robert Bosch | DE | 209 | 7399 | 19,090 | 39 |

CZ04 | Northwest | Ústí nad Labem | Metals | Plastics | −1.2 | 38.8 | 8724 | 4591 | 4729 | 5309 | PKN Orlen | PL | 16 | 4186 | 14,315 | 29 |

CZ05 | Northeast | Liberec | Motor | Metals | 4.3 | 41.3 | 8807 | 4643 | 6277 | 7540 | IVECO | IT | 234 | 6727 | 22,981 | 29 |

CZ06 | Southeast | Brno | Metals | Machinery | 8.2 | 44.2 | 9321 | 6209 | 7431 | 18,170 | Automotive Lighting | DE | 334 | 8364 | 27,760 | 30 |

CZ07 | Central Moravia | Olomuc | Metals | Plastics | 8.0 | 40.0 | 8665 | 5348 | 6061 | 9940 | Continental | DE | 58 | 4484 | 18,024 | 25 |

CZ08 | Moravian-Silesia | Ostrava | Metals | Motor | 6.8 | 43.7 | 9927 | 4963 | 6649 | 9635 | Hyundai Motor Group | KR | 12 | 8334 | 18,017 | 46 |

EE00 | Estonia | Tallin | Wood | Food | 5.7 | 43.1 | 11,558 | 8130 | 10,286 | 13,485 | Ericsson | SE | 245 | 19,924 | 23,615 | 84 |

HR03 | Adriatic Croatia | Split | Food | Metals | −2.8 | 36.5 | 10,965 | 8226 | 7956 | 11,053 | OTP | HU | N/A | 28,108 | 15,750 | 57 |

HR04 | Continental Croatia | Zagreb | Food | Wood | −0.3 | 36.5 | 10,670 | 7937 | 9373 | 15,156 | Deutsche Telekom | DE | 239 | 33,240 | ||

LV00 | Latvia | Riga | Wood | Food | 7.3 | 35.6 | 8434 | 6446 | 8013 | 14,510 | Uralchem | RU | 226 | 14,605 | 27,033 | 54 |

LT00 | Lithuania | Vilnius | Wood | Food | 15.0 | 38.4 | 8278 | 6758 | 7390 | 14,678 | PKN | PL | 20 | 14,816 | 42,191 | 35 |

HU10 | Central Hungary | Budapest | Food | Metals | 2.3 | 38.3 | 10,836 | 5583 | 9535 | 19,548 | General Electric | US | 55 | 43,261 | 53,045 | 82 |

HU21 | Central Transdanubia | Székes-fehérvár | Motor | Metals | 8.4 | 34.4 | 9233 | 3309 | 5235 | 6000 | Suzuki | JP | 66 | 7795 | 11,646 | 67 |

HU22 | Western Danubia | Gyor | Motor | Wood | 15.2 | 37.4 | 10,093 | 3795 | 6035 | 9333 | VW | DE | 6 | 11,846 | 12,452 | 95 |

HU23 | Southern Danubia | Pecs | Food | Electronics | 3.9 | 30.0 | 6636 | 3774 | 5419 | 12,139 | Flex | US | 74 | 1002 | 6847 | 15 |

HU31 | Northern Hungary | Miskolc | Electronics | Metals | 6.4 | 31.8 | 7737 | 3691 | 5276 | 9633 | Robert Bosch | DE | 23 | 3489 | 8732 | 40 |

HU32 | Northern Great Plain | Debrecen | Food | Electronics | 5.3 | 29.1 | 6136 | 3366 | 5205 | 8506 | Teva | IL | 215 | 4545 | 10,801 | 42 |

HU33 | Southern Great Plain | Szeged | Food | Plastics | 8.5 | 30.5 | 6811 | 4047 | 5273 | 8485 | Mercedes | DE | 25 | 2776 | 10,374 | 27 |

PL12 | Masovian | Warsaw | Food | Wood | 26.4 | 42.1 | 7811 | 6050 | 11,524 | 15,734 | Orange | FR | 40 | 95,721 | 94,978 | 101 |

PL21 | Lesser Poland | Krakow | Metals | Food | 14.7 | 33.4 | 7905 | 4166 | 6207 | 14,380 | Tesco | UK | 36 | 8106 | 33,943 | 24 |

PL22 | Silesian | Katowice | Metals | Motor | 14.8 | 36.7 | 10,298 | 5570 | 5358 | 8553 | ArcelorMittal | LU | 21 | 18,718 | 52,498 | 36 |

PL31 | Lublin | Lublin | Food | Wood | 10.0 | 20.4 | 4276 | 3071 | 2895 | 4586 | Maxima Group | LT | 348 | 1386 | 16,334 | 8 |

PL32 | Subcarpathian | Rzeszów | Plastics | Wood | 10.7 | 27.8 | 8389 | 3970 | 3704 | 6971 | Goodyear | US | 466 | 3619 | 16,631 | 22 |

PL33 | Holy Cross | Kielce | Metals | Plastics | 6.8 | 21.8 | 6531 | 2968 | 3348 | N/A | CELSA Group | ES | 327 | 1665 | 9957 | 17 |

PL34 | Podlaskie | Białystok | Food | Wood | 9.1 | 23.3 | 6118 | 3796 | 4087 | 4889 | BAT | UK | 128 | 514 | 9335 | 6 |

PL41 | Greater Poland | Poznan | Wood | Food | 18.5 | 39.0 | 9440 | 4932 | 9102 | 12,797 | Jerónimo Martins | PT | 4 | 15,842 | 42,120 | 38 |

PL42 | West Pomeranian | Szczecin | Wood | Food | 10.3 | 36.0 | 7148 | 3815 | 5202 | 13,136 | IKEA | SE | 163 | 3530 | 15,899 | 22 |

PL43 | Lubusz | Zielona Góra | Wood | Motor | 10.0 | 29.6 | 7161 | 2203 | 3668 | N/A | Krono Holding | CH | 435 | 1795 | 9476 | 19 |

PL51 | Lower Silesian | Wroclaw | Motor | Plastics | 17.9 | 39.3 | 10,126 | 4628 | 6294 | 10,287 | Schwarz Gruppe | DE | 49 | 9970 | 35,712 | 28 |

PL52 | Opole | Opole | Metals | Food | 9.9 | 30.5 | 7150 | 3792 | 3734 | N/A | Brenntag | DE | 482 | 1396 | 8786 | 16 |

PL61 | Kuyavian-Pomeranian | Bydgoszcz | Wood | Metals | 10.1 | 27.5 | 7031 | 4098 | 4327 | 3636 | Framondi | NL | 264 | 2605 | 18,872 | 14 |

PL62 | Warmian-Masurian | Olsztyn | Wood | Food | 9.5 | 24.7 | 6712 | 3288 | 3208 | N/A | VH Group | CN | 130 | 993 | 11,373 | 9 |

PL63 | Pomeranian | Gdansk | Wood | Metals | 13.7 | 30.3 | 7172 | 4126 | 4880 | 12,598 | Glencore | CH | 200 | 6415 | 24,855 | 26 |

RO11 | North-West | Cluj | Textiles | Wood | 9.7 | 21.8 | 4350 | 2515 | 2965 | 12,343 | MOL | HU | 148 | 4108 | 20,065 | 20 |

RO12 | Centre | Sibiu | Textiles | Motor | 10.2 | 26.6 | 5406 | 2432 | 3626 | 5292 | Daimler | DE | 102 | 6379 | 19,255 | 33 |

RO21 | North-East | Iasi | Textiles | Food | 8.1 | 14.8 | 3579 | 1318 | 2378 | 6192 | Delphi Technologies | UK | 498 | 1606 | 17,180 | 9 |

RO22 | South-East | Constanta | Textiles | Food | 14.1 | 24.2 | 4386 | 2497 | 3440 | 6280 | KazMunayGas | KZ | 51 | 3477 | 17,789 | 20 |

RO31 | South Muntenia | Ploiesti | Motor | Textiles | 10.4 | 23.9 | 5189 | 1693 | 2514 | 3973 | Renault | FR | 14 | 4837 | 20,859 | 23 |

RO32 | Bucharest-Ilfov | Bucharest | Food | Textiles | 37.2 | 50.0 | 11,414 | 6121 | 6895 | 16,954 | OMV | AT | 31 | 42,021 | 46,262 | 91 |

RO41 | South-West Oltenia | Craiova | Textiles | Food | 9.5 | 20.2 | 5009 | 3095 | 3231 | 5880 | Ford | US | 181 | 2080 | 12,328 | 17 |

RO42 | West | Timisoara | Motor | Textiles | 12.4 | 27.8 | 4916 | 3680 | 3478 | 14,536 | Louis Delhaize | BE | 187 | 5605 | 16,539 | 34 |

SI03 | Eastern Slovenia | Maribor | Metals | Wood | −2.9 | 54.5 | 17,185 | 13,477 | 11,642 | 9629 | Renault | FR | 98 | 2205 | 17,092 | 13 |

SI04 | Western Slovenia | Ljubliana | Metals | Electronics | −7.8 | 64.5 | 19,327 | 16,053 | 17,957 | 19,319 | Mercator | HR | 144 | 9121 | 21,772 | 42 |

SK01 | Bratislava Region | Bratislava | Motor | Other & repairs | 25.9 | 73.5 | 19,652 | 11,677 | 17,843 | 30,268 | VW | DE | 7 | 29,041 | 22,283 | 130 |

SK02 | Western Slovakia | Trnava | Metals | Plastics | 7.0 | 46.0 | 7542 | 2678 | 4737 | 3883 | Peugeot | FR | 41 | 5995 | 24,663 | 24 |

SK03 | Central Slovakia | Žilina | Metals | Wood | 8.6 | 43.0 | 7658 | 2293 | 5322 | 4386 | Hyundai Motor Group | KR | 13 | 3836 | 15,696 | 24 |

SK04 | Eastern Slovakia | Košice | Metals | Motor | 7.9 | 45.7 | 6659 | 2433 | 3252 | 7217 | US Steel | NL | 489 | 3392 | 16,497 | 21 |

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Szabo, S., Laguna, J.D. (2021). FDI as Force of Convergence in the CESEE Countries. In: Landesmann, M., Székely, I.P. (eds) Does EU Membership Facilitate Convergence? The Experience of the EU's Eastern Enlargement - Volume II. Studies in Economic Transition. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57702-5_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57702-5_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-57701-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-57702-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)