Abstract

Prior to the mid-1970, India’s non-economic social scientists had no role in policy, planning or implementation of resettlement, though their skills were relevant for the purpose and anthropologists had the requisite expertise. But anthropologists remained only distant onlookers of the terrible things that were happening in the name of development. In 1974 a historic change took place in the World Bank. This was the appointment of anthropologists and sociologists as regular staff. Thereafter, social concerns began receiving increasing attention in the Bank. This also resulted in a sudden demand for anthropologists and sociologists to prepare projects for Bank financing. India then also began involving anthropologists and sociologists in preparing projects involving social issues. From mere onlookers, they then became active participants in development activities.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

In the 1970s, the long ignored social and cultural factors in development gradually began to gain recognition in the World Bank. This was no small change. It was significant particularly because till then the World Bank had a strictly economic orientation, and there was little understanding of social issues that often arise in development work and which also need to be addressed.

In the wake of the Bank’s turning its face toward poverty reduction, an historic change took place inside the World Bank itself. This was the appointment of anthropologists and sociologists as regular staff, to help the Bank understand what it defined as the 40% poorest rural population. In 1974, the Bank created its first position of staff sociologist and Michael Cernea joined the Bank as its first social scientist, slowly followed by others. Thereafter, social concerns began receiving increasing professional attention in the Bank’s approach to development. This was then reflected in its concern to prevent social disasters resulting from infrastructure projects. With the support of his managers, Michael Cernea then proposed and drafted the first resettlement policy in the entire international donor and development community (World Bank 1980; Cernea 1993).

Social Scientists and Development in India

The impact of this and other subsequent social policies adopted by the World Bank was felt globally. The new social policies changed the social science scene in India as well. The big potential of India’s social scientists to work for development began to be used in very consequential ways.

Mere Observers

Prior to mid-1970, India’s non-economic social scientists had no role in policy, planning of development projects, or implementation of resettlement, though their skills and knowledge were relevant for these purposes. With few exceptions, anthropologists were distant observers of the socially terrible effects left behind by development projects. They were called to do little else besides teaching and studying. Anthropologists were just not needed in India’s major programs for development.

Active Participants

The World Bank issued in 1984 another operational policy, the OMS 2.20 on Project Appraisal, which contained the innovation-prone requirement that all Bank financed projects should incorporate in their preparation process (pre-appraisal and appraisal) a professional sociological analysis and an institutional analysis to complement the one-sided traditional economic and financial analyses required by the Bank before. This recognition of development variables previously neglected resulted in a sudden demand to borrowing countries for preparing more completely their projects for Bank financing; in turn, India also needed to involve Indian anthropologists and rural sociologists in the project preparation teams for social surveys, demographic and cultural assessments, resettlement planning, impact evaluation analyses. From mere onlookers, they then began to become active participants in development activities, including resettlement.

Anthropology in Government

The history of anthropological use in government programs in India were colored by its colonial status that ended when India became independent in 1947 (Vidyarthi: 1971). However, for the most part that history was confined to providing descriptive portrayals of tribal, caste, and minority groups, leaving to others the job of defining and promoting development. For example, the Anthropological Survey of India (an old institution established by the British colonial anthropologists in 1905) has been functioning uninterruptedly, but still remains focused on tribal ethnographies, as before. Academic anthropologists, too, have mostly continued to follow their interests largely around documenting the lifeways of tribal people and socially backward groups. Even most universities and independent researchers have chosen to follow the same path—so strong is the ethnographic research tradition that prevails even today, although more recently a dozen or so Tribal Research Institutes established in tribal dominated states are doing applied anthropological research on development issues of and for tribal people.

Role in Development

Gradually, the role of anthropologists expanded to the field of development, which then mostly meant programs of community development and tribal welfare (Majumdar 1960). But even there, the opportunities to introduce social knowledge into development policies and large programs were very limited. Only a handful of anthropologists were employed in various development agencies. In early 1950s, D. N. Majumdar, an eminent anthropologist from the Lucknow University, was invited to serve on the Planning Commission’s Research Programmes Committee. At about the same time, the Planning Commission set up a Programme Evaluation Organization to report independently on the performance of community development projects. The Commission went on to appoint anthropologist consultants. Similarly, S. C. Dube, a reputed anthropologist, was appointed to head the National Institute of Community Development. Some positions were also filled in at the Tribal Research Institutes (Mathur 1976). But the zest with which these development-oriented programs involving anthropologists were begun did not last long, and most soon lost steam (Mathur 1985).

Opportunities Lost

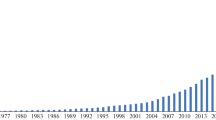

The large dam era began in India with a bang. From 1947 onwards, dam building started in a massive way, and within a short time a number of big dams came up. “Nearly 900 big dams were completed between 1951 and 1982” (Khagaram 2004: 37). Among the first dams built were Hirakud, Bhakra, Chambal, and Pong Dam. The human displacement caused by these dams was on an unprecedented scale, depriving millions of their homes, their livelihoods, often even their identity.

Here was a chance for the government to utilize anthropological expertise to resettle dam-displaced populations. Not only were the agencies unwilling to hear about the problems stemming from projects, but even national planners and representatives appeared to be uninterested in consulting Indian social specialists who could have at least flagged some of the most likely ways that these projects adversely affect their constituents. Preparing a national policy on resettlement was also a task for which anthropologists were best fitted. However, their role was not considered; the policy was seen as too important a matter to be left to anthropologists. Instead, the government preferred its own bureaucrats and other technical experts for the job, many of whom lacked any understanding or field experience with the complex social issues that were involved.

Surprisingly, anthropologists had no role in even such simple tasks as surveys to collect data required for planning purposes and for the evaluation of resettlement outcomes. They not only did not participate in externally funded projects, but they were left out even from those that the government funded itself. The frightening fact, however, is that the government often went ahead building dams with no consideration of their possible adverse social impacts (Singh and Banerji 2002). Unfortunately, such a situation has remained unchanged till today. A case study of a dam project in Orissa vividly documents the disastrous consequences of such a callous attitude on the poor tribal people (Agnihotri 2016).

Exclusion of Social Scientists

Often, the exclusion of social scientists occurred due to a plain desire of economists, bureaucrats and others to maintain their dominance in their organizations. In some cases, the cause of exclusion is also pure ignorance of the value and potential of anthropological knowledge for development work. There are also examples where anthropologists were brought in by organizations, but their expertise was not utilized for the purpose for which it was meant. For example, in 1995 the National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC), under World Bank pressure, turned to social science expertise for assistance in easing obstacles to its resettlement plans and the increase of farmer protests. They hurriedly inducted anthropologists and other social scientists to fix the problem. However, the lack of clarity in NTPC on the role of anthropologists led to their use as mere additional hands to assist project officials in carrying out displacement in ways usual to the NTPC organization with emphasis on simple removal of affected people to new sites rather than on simultaneously reconstructing their livelihoods. Unhappy with their other job conditions, most anthropologists soon left the organization, and the contracts of those remaining were cancelled once the World Bank project ended (Mathur 2013, also Mathur 2006).

Criticism of Flaws Is a Service for Better Development

Even when excluded from any role in government development projects, social scientists did not get passive and disheartened. They didn’t start grumbling over the rejection of their expertise—an understandable response. Instead, they responded positively and turned their expertise to serve the cause of development in pragmatic ways. Anthropologists and other social scientists provided on their own free services to development agencies by writing about the projects that were performing poorly (and there was no shortage of such projects). They looked into resettlement failures through their critical social scientists’ lens, offering constructive and detailed analyses that pointed out design or implementation flaws, together with the ways such shortcomings could be remedied. India’s resettlement literature abounds in such constructive critical anthropological studies. Examples include the detailed studies by Roy Burman (1961) and Karve (1969), to mention but a few. These studies did create some awareness that anthropologists do have the knowledge and skills to improve resettlement. But this awareness came too slowly to change the hardened bureaucratic mindsets in the short-run.

The Narmada Controversy

In the beginning of the dam era, government was able to build dam after dam, evicting hundreds of thousands of people from their homes and livelihoods without strong opposition. The dam-impoverished people felt the pain, but they didn’t openly express their accumulating anger. The affected people would take the paltry cash compensation on offer, hand over possession of their land for developmental uses, and move on to resettle at new places, often with drops in the quality of livelihood that lasted for generations (Mathur 1977). Opposition to dams was then almost non-existent. Gradually, things began to change as popular protests against dams surfaced from various Indian states. Initially, protesters’ demands were simple—better compensation for losses—and the methods of protest were entirely peaceful. As time went by, though, initial protests got bigger and better organized, and, with the infusion of much CSO support, they also became better organized and more militant,

Although displacement has gone on in India for decades, the resettlement issue came to the fore in a big way when controversy over the Narmada dam projects erupted in mid/late 1980s. Sardar Sarovar, one of the dams on the Narmada river, was causing massive displacement and relocation issues. As documented by Robert Wade’s in his Narmada paper in this volume, cracks and contradictions between the three affected states created opportunities for new political alliances. Medha Patkhar, a tenacious activist, led a powerful campaign against the Narmada projects, primarily Sardar Sarovar, denouncing both the Indian Government’s and the World Bank’s violations of its own poverty reduction and resettlement policies. This turned into a rallying cry calling for the complete stoppage of its construction, not just a better resettlement package. The agitation rapidly snowballed into something never previously anticipated—a social movement that was demanding a total ban on the building of dams not only in India, but all over the world.

In June 1991, the World Bank’s management, responding to this well organized and unstoppable protests,, appointed David Morse, formerly a head of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Thomas R Berger, a highly reputed Canadian jurist, and Hugh Brody, a British Anthropologist, to carry out an independent review of the Narmada Sardar Sarovar Dam’s social and environmental impacts, and on how India and the World Bank carried out their social and environmental responsibilities. On 18 June 1992, the Independent Review submitted its report on the Sardar Sarovar projects to the President of the World Bank. It confirmed the worst of the Narmada protesters’ criticisms. The report concluded, that the World Bank resettlement policy was adequate, but the World Bank and India’s central and state governments had ignored and violated it, and, by doing so, had violated the rights and destroyed the livelihoods of the affected populations, Morse et al. 1992: p. xii).

Impacts of the Independent Review’s Indictment on India

India felt the impact of Independent Review’s indictment directly. Following the success of protest against the Sardar Sarovar dam, strong protests against other dams sprang up in almost every nook and corner of the country. And no longer were the protests directed against dams alone; protests in other sectors, including industrial, mining, power, highways, and urban development also became the targets of NGO protests. In fact, against any project that caused displacement and ignored its resettlement obligations became their target. Today, no development project that fails to resettle displaced people adequately can escape the critical eye of one vigilant NGO or another.

The other consequences of the Independent Review include the following: Writing on resettlement issues has become something of a growth industry since the controversy over the Narmada dam projects broke out, intensifying long after the 1980s. Books, journal articles, conferences, and other research documents kept coming out. Examples include: Paranjpye (1990), Baviskar (1996), and Dreze et al. (1997). India’s resettlement literature became the largest in the world, and remains so today. The university departments of anthropology also saw the need to adapt their curricula to changed circumstances. With a rising number of students getting consultancy appointments on resettlement projects without any resettlement training or experience, most often with a mere degree in anthropology or sociology, forced them to include displacement and resettlement issues in their syllabuses. Consequently, the number of students pursuing resettlement as an optional subject because it opens up employment opportunities has steadily shown an upward trend. It is now quite common for students to select resettlement as a research topic for PhD in many other institutions, including even in such highly respected technical centers such as the Indian Institutes of Technology.

The most significant impact of protests, and the growing research output generated in its aftermath, though not immediately visible then, was slowly changing the mindset of India’s bureaucracy. They began to see the need for a law for better planning of resettlement. For example, the slow process of formulating a national policy on resettlement lingering for a long time, now began to be seen as a matter of some priority, but it dragged through several weak versions in 2004 and 2007 that did not go down well with the public, the NOGs, and the social scientists. Eventually, in 2013 India’s Parliament adopted a Law that for the first time brought land acquisition and resettlement within the same normative framework (GOI 2013), replaced the obsolete colonial 1894 Land Acquisition Act (Singh 2016). The extraordinary bargaining process and political battle for “the making of the 2013 Law” is described in detail in Ramesh and Khan’s 2015 book “Legislating for Justice”.

Impact of the Independent Review on the World Bank

Following the Independent Review, the World Bank moved fast and initiated several corrective measures to improve the resettlement work in the Bank. Another key area where the need to eliminate weaknesses was seen as a high priority was to ensure strict compliance with all its other social policies too. Another major concern was to improve implementation of projects in India. These initiatives meant much for India’s anthropologists, and sociologists, especially their role in development.

Implementing mandatory social policies, especially those related to the resettlement of those displaced, had opened vast new opportunities for anthropologists. But there were no takers for them, as the requisite expertise then did not exist on the scale required. In the beginning, the Bank attempted to carry out many of the resettlement and other poverty-oriented project assignments in India by sending out missions from its headquarters in Washington DC. Michael M. Cernea, William Partridge, Scott Guggenheim, Thayer Scudder, and Maritta Koch-Weser were among the staff and consultants who spent time working on resettlement projects in India.

The Bank, however, soon realized that it was not a practical or desirable solution to use the limited Bank staff from its headquarters to do the tasks that could well be done by local experts. But the lack of sufficient local capacity proved to be a big stumbling block. The first priority task, then, was to create it.

Building Capacity for Development Management

In India, development and resettlement issues emerged as a matter of overarching concern in the aftermath of Independent Review. Hence, the Bank turned its particular attention to equipping social scientists to capacity building for resettlement implementation, and took several measures, as follows.

-

(a)

Developing Resettlement Policies: Until 2004, India had no national policy. (States had their own ad hoc guidelines to address the resettlement problem). In the absence of a national policy on resettlement, the Bank applied its own resettlement policy to all projects in India that it financed. The Bank moved further. It soon began assisting the preparation of resettlement policies for those organizations to which it made big loans. Examples of World Bank projects that supported sectoral policy development include the; Orissa Water Resources Development Project, Mumbai Urban Transport Project, National Thermal Power Corporation Project, Coal India Project, and several others.

-

(b)

Hiring and Training National Staff and Short-term Consultants in the Bank’s New Delhi Office. In pursuance of its decision to build local capacity, the Bank created some staff positions for resettlement experts from India within the Bank’s New Delhi Office. Consequently, Sam Thangaraj, IUB Reddy, Mohammad Hasan, S Satish, Shankar Narayanan were among those appointed to the Social and Environment Division of the Bank’s New Delhi Office. This Division flourished under David Marsden, Elllen Schaengold, and others who followed them.

The New Delhi Office also engaged many local consultants on a short-term basis to carry out resettlement tasks as and when required. For example, they were employed to carry out a variety of tasks that included: social impact assessments, resettlement planning, implementation, evaluation, supervision, monitoring, preparation of project completion reports, assisting Bank’s inspection panel, and so on. It is impossible to estimate in retrospect the number employed as short-term consultants, but the number must be huge.

-

(c)

Building a Resettlement Curriculum: The scarcity of relevant training material was immediately recognized as a big hurdle in conducting this programme. No training material, no other publication existed, explaining involuntary resettlement issues for resettlement practitioners in an easily comprehensible way. The World Bank, at the very start, took a decision to commission such a publication consisting of a series of case studies on resettlement experience in different project types in India, which could be used for training purposes. As part of my own first assignment with World Bank, I worked to produce a casebook on managing resettlement caused by dams, mining and other kinds of projects.

-

(d)

Training for Resettlement Practitioners: The next major step that the World Bank took to fill in the expertise lacunae was the launch of a training programme for planners, practitioners, researchers and NGOs involved in resettlement activities. In 1993, the Economic Development Institute (EDI) of the World Bank, Washington, was assigned this responsibility for the entire world, but this particular training programme focused on India and China for the obvious reason—these two countries were causing the most resettlement issues. EDI appointed Gordon Appleby, an anthropologist, as the overall coordinator for the EDI training programme, with two separate consultants, one each for India and China. For India, I was appointed as consultant and served intermittently from 1995 to 1999.

Resettlement training workshops were initiated in 1994, in Hyderabad, and were then extended to most state administrative training institutes in India, including Udaipur (Rajasthan), Mysore (Karnataka), Bhopal (Madhya Pradesh), Pune (Maharashtra), Bhubaneswar (Orissa), Nainital (Uttar Pradesh), Kolkata (West Bengal), and also Mussoorie (National). One workshop was also conducted for industry manages in collaboration with the Confederation of Indian Industry, as the private sector’s role in development was becoming increasingly important. By the time the EDI programme ended in 1999, it had produced a large pool of trained resettlement practitioners, trainers, NGOs, resource persons and a useful publication for training purposes (Mathur 1997).

-

(e)

Support to Training by Correspondence The Bank’s New Delhi Office also provided support to an Open University in New Delhi to run a correspondence course. With Shobhita Jain as the Director of this programme and Madhu Bala as her associate, the programme ran well and trained many in-service resettlement staff doing resettlement without any prior training.

-

(f)

The World Bank’s Support to National Seminars: The World Bank headquarters sponsored several resettlement seminars in India. These included the following:

-

Seminar at ISEC Bangalore: One such early seminar was held at the Institute of Social and Economic Change in Bangalore in 1979. The key presenter in this Seminar was Scott Guggenheim from the Bank who elaborated on Cernea’s Impoverishment Risks Model. The seminar also came up with a set of recommendations for preparing a National Resettlement Policy. A summary of this seminar was later published by ISEC for wide distribution (Aloysius 1990).

-

Seminar on Impoverishment Risks, New Delhi: 1994, another important seminar was held in New Delhi. This took place at the initiative of David Marsden who was then heading the Social and Environment Division in the Bank’s New Delhi Office. The seminar was focused on Cernea’s Impoverishment Risks Model. Later, David Marsden, at Michael Cernea’s suggestion, invited me to prepare a volume based on the papers presented at this seminar, which was published with the title Development Projects ad Impoverishment Risks.

-

The Simla Seminar on South Asia Region R&R Sourcebook; Ms Ellen Schengold, who succeeded David Marsden as Chief, Social and Environmental Division in the Bank’s New Delhi Office, organized yet another important seminar in Simla in June 1998. The purpose was to familiarize the seminar participants with the World Bank’s just published ‘South Asia Region R&R Sourcebook’. Participants attended the Seminar from all over India from a variety of backgrounds: government, research organizations, NGOs, and consultants. From the Bank headquarters, several staff members and consultants also came over to serve as faculty.

-

The National Seminar on the South Asia Region Resettlement & Rehabilitation Sourcebook: The Bank recently supported the Council for Social Development to organize a national seminar to discuss the draft Land Acquisition Rehabilitation and Resettlement Bill 2011. The objective of the workshop was to formulate comments and recommendations on the draft bill from the perspective of both the people affected by land acquisition and resettlement, and that of the land requiring agencies, and to send these to the government for their consideration while finalizing the Bill. The participants included experts from the Council and elsewhere, social activists, academics, representatives of project authorities and land requiring agencies, NGOs, serving and retired civil servants, and World Bank staff.

-

-

(g)

Participation in International Seminars and Conferences—The Bank supported the participation of a large number of India’s social scientists, consultants and NGOs in international conferences held at various places around the world. Examples include the following:

-

World Bank Seminars on Involuntary Resettlement in Bank-financed Projects in Asia: An International Seminar titled ‘World Bank Consultants Seminar on Involuntary Resettlement in Bank-financed Projects in Asia’ took place in Washington DC at the Bank’s headquarters and also at Baltimore, Maryland in June 1990. Participants from several Asian countries attended this seminar, including participants from India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Vietnam. This training seminar was designed to develop local capacity for managing Bank-funded and other resettlement projects. A volume jointly edited by Mathur and Cernea (1994) based on Asian resettlement papers presented at this training programme was later published.

The World Bank also extended support for Indian social scientists to attend international conferences organized by other professional organizations, where participants could exchange knowledge and build cross-country networks. Among these were: (a) Xth World Congress of Rural Sociology, held at Rio de Janeiro (30 July 5 August 2000), and (b) A session on ‘Population Resettlement and Environmental Risks’ which was part of the larger IAPS/Biblex Conference on ‘Environment, Health and Sustainable Development’, held at Alexandria (11–16 September 2006).

-

Overall Feedback on Training Workshops and Seminars: The feedback from participants from these training workshops and seminars can be summed up as follows: Participants were unanimous in their view that what they had learned was going to be of immense help in efforts to improve their performance on resettlement operations in India. In addition, they felt that such programmes provided an excellent platform for Indian social scientists to meet and interact with their colleagues from different projects, places and backgrounds. Among those who participated in these various seminars, included Aloysius Fernandes, Vasudha Dhagamwar and L. K. Mahapatra, Ramaswamy Iyer, N. C. Saxena, A. B. Ota, IUB Reddy, Balaji Pandey, Anita Agnihotri, Walter Fernandes, Enakshi Ganguli Thukral, Malika Basu, Achyut Das, S. M. Jammdar, S. Parasuraman and several others.

-

Enriching Resettlement Knowledge

Social scientists of India and the World Bank together have contributed enormously to the publication of research-based books, articles and other publications on resettlement issues. The research output carried out both in India and the World Bank is indeed very impressive and also of a high quality. The difference is that while literature produced in India is more rooted in on the ground situations, the Bank’s contribution is more tilted towards the macro side, both complementing each other’s efforts.

Much contribution from the Bank is relevant to the Indian situation as well. Cernea himself has contributed several chapters and articles to many publications in India. These include: Mathur (1985, 1994, 1995, 1997, 1998, 2006, 2008, 2016), Parasuraman (2000) and Jain and Bala (2006), among others. He also contributed to a number of articles in Indian journals including Economic and Political Weekly (1996, 2007), The Eastern Anthropologist (2000), and Social Change (2006). In addition, Cernea also jointly edited a couple of books (Mathur and Cernea 1995; Cernea and Mathur 2008)

In turn, many Indian anthropologists and sociologists have written for World Bank publications. They include: Behura and Nayak (1993), Mahapatra (2000), Fernandes (2000), Hakim (2000), Nayak 2000), Appa and Patel (1996) and Thangaraj (1996). In addition, Mathur (1977) prepared a publication based on resettlement experience in Rajasthan, which was published by World Bank/EDI).

Initially, most research in India was “damcentric”. Later, as projects in other development sectors began overtaking dams as a major driver of displacement, the area of research expended to cover them as well. Examples include, dams (Ganguly Thukral 1992) industry (Dhagamwar et al. 2000), mining (CSE), urban (Modi 2009), highways (Mridula Singh), women and displacement (Mehta 2000), development impact on tribal cultures (Felix and Das 2010), and conservation in protected parks (Kabra 2018), among several others. Several specific resettlement issues too have figured prominently, and these include: Impoverishment risks (Mathur and Marsden 1998; Mahapatra 2000; Bharali 2015), Ethnography of land acquisition (Guha 2011), and, Social Impact Assessment (Mathur 2016).

Finally, a widely known contribution from India is the Resettlement News. Edited by Hari Mohan Mathur, it reports on current operational, research and capacity building work in resettlement from around the world. The aim is to disseminate practical experience, ideas and information among those working in resettlement agencies, development research centers and management training institutes. This newsletter is published twice a year in January and July, and is regularly uploaded on the INDR website (www.displacement.net).

Summing Up

The building of big dams began in India soon after India became independent in 1947. Big dams together with a number of projects in other development sectors that followed soon resulted in displacement, which was truly unprecedented and on a vast scale. Yet, resettling affected people remained a low priority in development planning. Initially, anthropologists who could contribute to resettlement effort were not involved in any such activity; their participation in government development programmes remained confined mostly to planning and implementing tribal welfare schemes. Anthropologists felt left out at their role reduced to that of mere observers of development. They gave expression to this frustration in the form of their analytical studies critical of the unfolding disastrous events.

Around 1970s, things took a turn for the better for India’s social scientists when finally they got an opportunity to do resettlement as active participants, a significant change from being mere observers for so long. In India, the research findings by its own anthropologists also slowly brought about a change in the perception prevailing about the relevance of anthropological knowledge to development and resettlement, though this change was at a pace too slow to make any immediate difference to the situation. But the trigger that made the real quick difference was the Bank policy on resettlement, first issued in 1980, and the follow-up work undertaken to help turn the overall policy into operational procedures, skills, and practices. This created a huge demand for anthropologists who could help reduce the damage stemming from the problem of resettling displaced people.

The capacity required to couple field research with policy development and operational support to programs was scarce, and had to be built up almost from scratch. While NGO advocacy and demands for accountability continue to press for better standards and more careful consideration of the human costs of displacement, India’s social scientists also worked closely with their counterparts in the Bank to build capacities and skills. While there is still a long way to go, this partnership succeeded in strengthening the required planning and management skills in resettlement and other social policies and projects in India, which has helped mitigate the worst effects of displacement and offered displaced communities a better chance at recovering their livelihoods and future prospects.

References

Agnihotri, A. (2016). Building Dams, ignoring consequences: The Lower Suktel Irrigation Project in Orissa. In H. M. Mathur (Ed.), Assessing the social impact of development projects: Experience in India and other Asian countries (pp. 75–86). Cham: Springer.

Aloysius, F. P. (Ed.). (1990). Workshop on rehabilitation of persons displaced by development projects. Bangalore: Institute for social and economic change.

Appa, G., & Patel, G. (Eds.) (1996). Unrecognized, unnecessary and unjust displacement: Case studies from Gujarat, India. In C. McDowell (Ed.), Understanding impoverishment: The consequences of development-induced displacement (pp. 139–150). Oxford: Beghahan Books.

Baviskar, A. (1996). In the belly of the river: Tribal conflicts over development in the Narmada Valley. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Behura, N. K., & Nayak, P. K. (1993). Involuntary resettlement and the changing frontiers of kinship: A study of resettlement in Orissa. In M. M. Cernea & S. E. Guggenheim (Eds.), 1993 Francesco, Oxford (pp. 283–306).

Bharali, G. (2015). The application of IRR model in involuntary resettlement research in India. Paper presented at the SFFA 2015 annual meeting held in Pittsburgh PA.

Cernea, M., & Mathur, H. M. (Eds.). (2008). Can compensation prevent impoverishment? Reforming resettlement through investments and benefit-sharing. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Cernea, Michael M 1993 “Anthropological and Sociological Research on Policy Development on Population Resettlement” in Michael M Cernea, and Scott E Guggenheim (Eds) 1993 Anthropological Approaches to Resettlement: Policy, Practice, and Theory Boulder, CO: Westview Press (pp 13–38)

Dhagamwar, V., De, S., & Verma, N. (2000). Industrial development and displacement. New Delhi: Sage.

Dreze, J., Smson, M., & Singh, S. (Eds.) (1997). The dam and the nation: Displacement and resettlement in the Narmads Valley New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Fernandes, W. (2000). From marginalization to sharing project benefits. In: M. M. Cernea & C. McDowell (Eds.), Risks and reconstruction: Experiences of resettlers and refugees (pp. 205–226). Washington, DC: World Bank.

GOI. (2013). The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act 2013. New Delhi: Department of Land Resources, Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India.

Guha, A. (2011). Special economic zones, land acquisition and civil society in West Bengal. In H. M. Mathur (Ed.), Resettling displaced people in India: Policy and practice in India. New Delhi: Routledge (London and New York).

Hakim, R. (2000). The creation of community: Well-being without wealth in an Urban Greek locality. In M. M. Cernea & C. McDowell (Eds.), Risks and reconstruction: Experiences of resettlers and refugees (pp. 229–252). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Jain, S., & Bala, M. (2006). The Economics and politics of resettlement in India. New Delhi: Dorling Kindersley (India) Pvt Ltd., (Licensees of Pearson Education in South Asia.

Kabra, A. (2018). Dilemmas of conservation displacement from protected areas. In Cernea, M. Michael, & J. K. Maldonado (Eds.), Challenging the prevailing paradigm of displacement and resettlement: Risks, impoverishment, legacies, solutions. London and NewYork.

Karve, I. (1969). A survey of the people displaced by Koyna Dam. Poona: Deccan College.

Khagaram, S. (2004). Dams and development: Transnational struggles for water and power. New York: Cornell University Press.

Mahapatra, L. K. (2000). Testing the risks and reconstruction model on India’s resettlement experiences. In M. Cernea (Ed.), The economics of involuntary resettlement (pp. 189–230). World Bank.

Majumdar, D. N. (1960). Social contours of an industrial city: Social survey of Kanpur 1954-56. New York: Asia.

Mathur, H. M. (1976). Anthropology, government, and development planning in India. In: D. Pitt (Ed.), Development from below: Anthropologists and development situations (pp. 125–138). The Hague: Mouton.

Mathur, H. M. (1977). Managing projects that involve resettlement. Case studies from Rajasthan, India. Washington DC: World Bank: EDI.

Mathur, H. M. (1985). Anthropology in government of India’s development programmes. Development Anthropology Network (Bulletin of the Institute for Development Anthropology, New York), 3(1), 10–13.

Mathur, H. M. (1994). Resettling development-displacement populations: Issues and approaches. The resettlement of project-affected people; proceedings of a training seminar. Jaipur, The HCM Rajasthan state institute of public administration.

Mathur, Hari Mohan 1995 The Resettlement of Project-Affected People: Proceedings of a Training Seminar Jaipur: The HCM State Institute of Public Administration, Jaipur

Mathur, Hari Mohan 1997 Managing Projects that Involve Resettlement: Case Studies from Rajasthan, India Washington DC:The World Bank/EDI

Mathur, H. M. (1998). The impoverishment risk model and its use as a planning tool. In H. M. Mathur & D. Marsden (Eds.), Development projects and impoverishment risks: resettling project-affected people in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Mathur, H. M. (2006). Managing resettlement in India: Approaches, issues, experiences. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Mathur, H. M. (Ed.). (2008). India social development 2008: Development and displacement. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Mathur, H. M. (2013). Displacement and resettlement in India: The human cost of development. London: Routledge.

Mathur, H. M. (Ed.). (2016). Assessing the social impact of development projects: Experience in India and other Asian countries. Cham: Springer.

Mathur, H. M., & Cernea, M. M. (Eds.). (1994). Development, displacement and resettlement: Focus on Asian experiences. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House.

Mathur, H. M., & Cernea, M. M. (Eds.). (1995). Development, displacement and resettlement: Focus on Asian experiences. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House.

Mathur, H. M., & Marsden, D. (Eds.). (1998). Development projects and impoverishment risks: Resettling project-affected people in India. New Delhi: Oxford University.

Mehta, Lyla (Ed) 2000 Displaced by Development: Confronting Marginalisation and Gender Justice New Delhi: SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd

Modi, R. (2009). Resettlement and rehabilitation in urban centres. Economic & Political Weekly, 44(6), 20–22.

Morse, B., Berger, T., & Brody, H. (1992). Sardar Sarovar: The report of the independent review. Ottawa: Resources Futures International.

Nayak, R. (2000) Risks associated the landlessness: An exploration toward socially friendly displacement and resettlement. In M. M. Cernea & C. McDowell (Eds.), Risks and reconstruction: Experiences of resettlers and refugees (pp. 79–107). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Padel, Felix and Samarendra Das 2010 Out of this Earth: East India Adivasis and the Aluminium Cartel New Delhi: Orient Blackswan

Paranjpye, V. (1990). High dams on the Narmada: A holistic analysis of the river valley projects. New Delhi: Indian National Trust for Arts and Cultural Heritage.

Parasuraman, S. (2000). The dilemmas of development: Displacement in India. Delhi: St. Martin Press.

Roy Burman, B. K. (1961). Social processes in the industrialization of Rourkela. New Delhi: Census of India.

Singh, S. (2016). Turning policy into law: A new initiative on social impact assessment in India. New York, London: Springer Cham, Heidelberg, Dordrecht.

Singh, S., & Banerji, P. (Eds.). (2002). Large dams in India: Environmental, social and economic impacts. New Delhi: Indian Institute of Public Administration.

Thangaraj, S. (1996). Impoverishment risks: A methodological tool for participatory resettlement planning. In C. McDowell (Ed.), Understanding impoverishment (pp. 201–252). Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Thukral, E. G. (Ed.). (1992). Big dams, displaced people: Rivers of sorrow rivers of change. New Delhi: Sage.

World Bank. (1980). Social issues associated with involuntary resettlement in bank-financed projects, OMS 2.33. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Mathur, H.M. (2021). From Onlookers to Participants: How the Role of Social Scientists Has Changed in India’s Development in the Last 70 Years. In: Koch-Weser, M., Guggenheim, S. (eds) Social Development in the World Bank. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57426-0_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57426-0_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-57425-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-57426-0

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)