Abstract

This article first presents reflections on the joint work carried out by Michael Cernea and this chapter’s author over 8–9 years for gaining “room, recognition and resources” within the CGIAR for sociological and socio-anthropological research on farmers, their practices and needs. The status of social research inside the CGIAR has gone through ups and downs in the uphill battle for expanding social research and feeding its findings into the Centers’ biophysical and genetic improvement research has been a constant in CGIAR’s history. The chapter then documents the contribution of Michael Cernea, the first sociologist who acceded to CGIAR’s top science and policy bodies, to strengthening the presence and influence of sociological and anthropological knowledge within the CGIAR’s institutional architecture and scientific products and outcomes.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Anthony Bebbington’s essay profiling the development thinking and contributions of Michael Cernea in the anthology dedicated to Fifty Key Thinkers on Development (Simon 2006) described how Cernea explains to his students both the attractions and the challenges of practicing development anthropology and sociology, by using a metaphor from athletics. “Practicing development anthropology—Michael is warning them—is a contact sport” (Bebbington 2006).

Really?! How could this elegant and reflexive academic discipline be seen and compared to a “contact sport” ? Therefore, when I myself also heard Michael Cernea using the same metaphor, I asked him, point blank, to be more explicit. He answered: “Practicing development social science needs people who not only have brains, but also are ready to stand and fight for their convictions; people who not only have knowledge, but also do have action-oriented minds; and people whose social science knowledge is doubled by a fair and moral compass. In sum, development anthropology demands sharp insight and character.”

I had the privilege of working closely for nearly one decade with Michael Cernea and saw first-hand how the work of a militant “contact anthropologist” is unfolding. This article will share my reflections on our joint work in the CGIAR, during which we battled for getting CG’s Centers to employ sociological and anthropological research on agriculture’s central actor: the farmers, their production systems, households, communities, and institutions, not only research on the, biophysical, genetic and technical variables of the agricultural process.

The CGIAR (Consultative Group on International Agriculture Research) was established in 1971 as a global consortium of pre-existing agricultural research centers.Footnote 1 Each center had a different specialization, but they shared a common goal: to enable the world’s agriculture to feed the world and eradicate hunger. However, their common characteristic was that all were limiting themselves to carry out only technological research on plants, animals, soil, and water.

What was missing, both conceptually and in terms of staffing, was the deliberate orientation and a robust professional capacity to research agriculture’s most important component: its human actor, the farmers themselves, their production systems, and farmers’ behavior as producers. Those disparate centersFootnote 2 were staffed only with technical specialists—e.g., geneticists, plant breeders, agronomists, biologists, crop physiologists, water specialists and other technical experts, each outstanding in his or her specialty; however, paradoxically, they were totally lacking social researchers such as anthropologists or rural sociologists. In sum, CGIAR’s initial paradigm for improving the developing countries’ agriculture was narrow, in that it was conceived to do research only on agriculture’s natural and technical variables.

Consistent with the general theme of the present volume, this chapter attempts to reconstruct in broad lines the gradual process through which the CG consortium of research institutions and scientists has evolved—I must say, rather slow, and with fits and starts—towards the recognition that CG’s narrow paradigm of technical research must necessarily be broadened to encompass also the social, economic, and cultural/behavioral variables of agricultural development. That process included the recognition that CGIAR must also rely on knowledge available from social sciences, and also that CGIAR as a comprehensive system must itself produce such social knowledge, to complement its biophysical and technological research. In other words, CGIAR had to complement its staff with scholars in social sciences and with professional social researchers, in order to gain additional ‘lenses’ trained upon the farmer as agriculture’s central actor, his production systems, family, and the knowledge farmers have—or lack—about how to self-organize and carry out their hard and incessant work.

A Brief Comparative Look at CGIAR and the World Bank

Both the World Bank and the CGIAR are major global institutions which have influenced and contributed—in different ways and proportions—to the fundamental international shift from the initial narrow pursuit of economic development (the WB) and, respectively, the narrow pursuit of technological development (the CG), to today’s broader paradigm of social development.

Some of these ways have been partly interdependent and converging, and, over time, the World Bank as a major institution and its community of its social specialists have tenaciously ‘nudged’ the CG to also move in the same direction.

An eminent anthropologist, Scott E. Guggenheim, who has worked for years in both the CG and in the World Bank, observed that “the two institutions may be usefully compared”. He outlined this comparison retrospectively, in 2006, writing:

Both institutions have global mandates. Both have gone through far-reaching reorganizations and introspective examinations of their role, whose objective has been to align institutional mandates and procedures to the global objective of poverty reduction. Both institutions first began experimenting with using social scientists in mid-1970s (World Bank on its own decision, and CGIAR due to some pump-priming support offered by the Rockefeller Foundation which financed a post-doctoral programme that would, in principle, later to be taken up by CGIAR core budgets).

However, the trajectory of social scientists in the two institutions has diverged. In the World Bank the leading social scientists have moved from only supporting operational projects towards playing a growing role in formulating social policies and development strategies, so much so that even IMF-World Bank macro-level adjustment programs increasingly incorporated social science team members. Social scientists have also come to play a bigger role in rural development programs.... By contrast, CGIAR doesn’t appear to have capitalized well on the splashy start enabled by its generous Rockefeller support... In addition, while the World Bank has funded a Social Development Department and Network at the World Bank’s center to offer guidance across the Bank’s system, CGIAR has nothing of this kind at its headquarters (see more on this comparison in Guggenheim 2006, pp. 425–426).

Given that a comprehensive history of the CGIAR, regretfully, has not yet been written, this rich history is far less known than it fully deserves, due to CG’s immense contribution to increasing our world’s capacity to feed itself. Therefore, this essay attempts also to reconstruct several key pages from CG’s overall history. These pages are capturing and describing with their factual evidence significant events and moments of the gradual shift of CG from its initial technical research model oriented exclusively on biophysical and genetic components of the agricultural production process toward embracing and practicing a more encompassing research paradigm—one that took account and included also the study of the determinant social and cultural drivers of agricultural development.

The “Rocky-Docs” and the Fight to Overcome the Absence of Social Research in CGIAR

Soon after CGIAR was created in the early 1970s, discussions started among donors regarding the need to complement CG’s agro-technical research with anthropological and sociological research on farmers, their needs and productive behavior. Nonetheless, the Centers weren’t quite acting in this direction.

Therefore, in 1974 the Rockefeller Foundation (RF), in consensus with the World Bank and the UNDP, launched a strategically tailored initiative: it conceived and funded a Social Science Fellowship Program that aimed to create inside the CGIAR the professional capacity able and indispensable for carrying out social research focused on farmer’s work, practices, needs and knowledge. This critical RF external initiative created a range of slots across the CG Centers to be staffed by specially recruited young and promising PhDs in social sciences. They became the first cohort of professionally trained social specialists working in the CG Centers: sociologists, anthropologists, economists, social geographers and cultural ecologists. They brought along a body of new knowledge: social knowledge and social methodologies, that is, capabilities previously missing in the CG’s Centers. By joining the traditional pattern of multidisciplinary teams of eminent scholars and researchers specialized in other disciplines. Overall, as an evaluation paper authored by RF experts assessed after a number of years, the substantial contributions of this cohort of social specialists has broadened and enhanced CGIAR’s capacities to understand and address the human-behavioral complexities of agricultural improvement (see Conway et al. 2006).

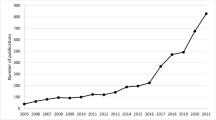

Over the next 22 years this program placed 114 young ‘Rocky-Docs’ in CGIAR and its associate centers. Some of these social researchers were retained in the core staff by the Centers themselves. Yet, considering that the CGIAR had 15–16 Centers, and that most of the social researchers stayed on their RF fellowship slots only between 1 and 3 years, their spread inside the CG was still pretty thin and insufficient. On an annual basis, the average number of social researchers working at the same time each year in the entire CGIAR amounted to about 30–35, which still was by far less than reaching the needed “critical mass”. The RF initiative also helped the CG Centers to extend their outreach to some national agricultural research systems and incorporate farmers into problem identification. The RF program also had the distinction of long being the single major source for channeling female scientists, some 43 of them, into the CGIAR centers.

Nonetheless, the newly recruited Rocky-Docs, social anthropologists and sociologists, didn’t have it easy in their first years. One substantive difficulty was comparable with the difficulty that, at the World Bank, was encountered by its first sociologists and anthropologists. That difficulty was properly described by Scott Guggenheim, an anthropologist who worked alternatively in both institutions (World Bank and CGIAR) and coined the concept of “trained inattentiveness” of many excellent economists to the social variables of projects and, respectively, many excellent biophysical scholars and researchers. Guggenheim wrote:

If keeping an eye on the technological ball was a key virtue of CIAT’s excellent biophysical scientists, their trained inattention to the sociological and organizational determinants of what makes technology useful to poor farmers was an eye-opening experience... (Guggenheim 2006, p. 426).

Moreover, in most CG Centers the Rocky-Docs were long still prejudged and seen as “imported”, rather than intrinsic and essentially relevant to the processes to be dealt with.

A consequence inside the CGIAR of this kind of second rank, ‘late comer’ and ‘secondary status’, the social sciences did not have a “voice” in CGIAR’s top forum and the CG’s central brain-trust, the Technical Advisory Committee. By “voice” I mean a member of that top guidance body, a scholar in sociology or anthropology who would knowingly speak for the potential and the role of the social scientists in the research programs and working plans of each CG Center. This, of course, did not help their work and roles, and limited their influence in the CG’s research projects.

The first large, collectively prepared, and widely noticed affirmation of the research “products” of the Rocky Docs was the conference they organized at end of the 1970s with UNDP support titled “Exploratory Workshop on the Role of Anthropologists and Other Social Scientists in Interdisciplinary Teams Developing Improved Food Production Technology”, held at IRRI, reflected also in a publication (IRRI 1981). The workshop was attended, among others, by some of the standard bearers of social research in the CGIAR and by some outside scholars: Susan Almy, Jacqueline Ashby, Benjamin Bagadion, Gelia Castillo, Grace Goodell, Robert Herdt, Romana de los Reyes, Robert Rhoades, Richard Sawyer and Robert Werge.

Besides the fieldwork research findings reported in the workshop’s papers, participants together with some of the CG managers agreed upon a set of policy recommendations to address fundamental questions related to the role of anthropologists in interdisciplinary teams developing improved food production technology. In this way, the event marked a step forward in the status of social scientists in CGIAR, defining the area of CG’s social problems and pointing out specific social methodologies beneficial for CGIAR:

Specific research topics in agricultural development, which directly or indirectly involve human beings in their physical, social, or cultural nature, are as numerous as the concerns of the research institutions as a whole. Anthropologists and other social scientists must contribute to the definition and solution of these problems at all stages. They must work jointly with the institution’s scientists of other disciplines....The social anthropologist has a role to play in an organization developing improved food production technology by increasing efficiency through process-oriented rather than product-oriented activities. (IRRI 1981)

Following that very good workshop, research by CG’s social specialists gained a lift and diversified during the 1980s. Examples of such research are described in detail by their authors in the volume edited by Cernea and Kassam (2006), such as CIP’s incorporating a new path—‘from farmer back to farmer’—into the center’s research strategies; CIAT’s research experiments on farmers’ fields, that expanded afterwards to farmer-managed experiments and to farmer-led participatory plant breeding; the pioneering sociological research done by Murray and Vermillion (IWMI) on farmers’ organizations proven potential for managing irrigation systems; the methodological contribution to the research methods of CGIAR, produced by the sociologists working at CIAT, led by Ashby (see Ashby 1986) who dealt with the participation of small farmers; the research at IFPRI, led by Meinzen-Dick, who dealt with collective action and property rights issues, and research that continued for many years (see Meinzen-Dick 2006)

However, as will be seen later, the flowering of interest in social research in the CGIAR system generated by the ‘Rocky-Doc’ initiative did not take permanent and deep roots in the system. When the RF funding ended, several CG Centers did not take over the costs of the Rocky-Docs positions, as was the premise of the RF’s early support strategy. Many had to leave. As a result, the CGIAR system remained weaker than it could be today through organically integrating social research, and ecological research, into the mainstream CGIAR agenda. For this, as will be evident from this chapter’s end section, it is regarded quite critically in the outside academic community of social scientists specialized in agriculture, who are university based.

The World Bank’s Influence on CG’s Research

It was for the first time in the history of the CGIAR, after 27 years of existence, when an eminent sociologist, Michael Cernea, was appointed to its top scientific council: the TAC (Technical Advisory Committee), later renamed as CGIAR’s Scientific Council (SC). Cernea’s appointment to the TAC was recommended in 1997 by the three international organizations sponsoring the CGIAR: the UNDP, the FAO, and the World Bank. At that time I was the senior staff specialist in the Secretariat of CGIAR’s TAC, located at FAO in Rome, and interacted with Cernea since his joining the TAC.

Even before joining the World Bank Michael Cernea already had a prominent national and international status as a sociology scholar specialized in rural societies. Europe’s rural sociologists had elected Cernea in 1973 as Vice-President of the European Society for Rural Sociology.Footnote 3 In fact, his rural research-focus and specialization—‘the economic thinking and rationality of peasants’—had weighed heavily in his hiring in 1974 by the World Bank’s central agricultural department. Thus, Michael came to CGIAR after a long and brilliant career of nearly a quarter century in the World Bank, which earned him the high responsibility of Senior Advisor for Social Policies and Sociology to the World Bank’s management; he also had the principal role in building and leading the Bank’s large community of social specialists; (at his retirement in 1996 there were already 160 regular staff social specialists; “As of 2020, social development could count on more than 300 professional staff throughout the World Bank Group” (pers. comm. Louise Cord, Director, Social Development, World Bank, October 2020). He had been known in CGIAR long before he joined it, too, because during his decade of work in the Bank’s central AGR Department he interacted with CG’s social researchers and did involve some in Bank projects and joint social studies (see Meinzen-Dick and Cernea 1984).

The natural basis of CG-World Bank continuous collaboration was the commonality of their central objectives of improving agriculture and reducing rural poverty. Over the years, the Bank became the institution which supported and influenced intellectually and supported financially the CGIAR more than any other organization in many respects, including also in broadening its social research on farmers’ needs and capacities. What CG’s social specialists placed by RF in CGIAR were advocating—a broader and more intense focus on farmers—was what the Bank was already doing; and this became an impetus for CG too.

On the Bank’s side, the main engine driving this Bank-intended influence was the Bank’s central agricultural department, led by Montague Yudelman, himself a highly reputed South-African agricultural researcher of small farmers’ productivity; AGR’s deputy directors, Leif Christoffersen and Don Pickering, as well as its senior advisers on crops and research, John Russell and John Coulter, and later another senior adviser, Jock Anderson, were largely focused on the Bank’s numerous projects in Asia and Africa that financed the creation of state managed social systems for the organized extension to farmers of science-based recommendations for their practices. In this context, Michael was tasked to study on-the-ground in India how India’s extension projects were implemented and performing, and to design a system for monitoring the extension apparatus and its impact of the farmers’ knowledge; monitoring was still an innovation at that time. Written jointly with a statistician, the study that outlined a comprehensive monitoring system became Cernea’s first Bank publication (Cernea and Tepping 1977). Shortly thereafter, Michael initiated two collective books on “knowledge from research to farmers” (Cernea et al. 1983), which were sent by the Bank to all the countries with Bank-financed extension projects, and to all CG’s research centers. Encouraged after these three publications Michael started working on what was to become in the following years the classic, landmark book “Putting People First. Sociological Variables in Rural Development” (Cernea 1985/1991), with wide international impact.

To conclude this too rapid overview on how the World Bank’s worked with, nudged and influenced CG’s gradual paradigm shift and broadening, I’d like to mention another most potent Bank lever for influencing CG’s research orientation. CG’s founders agreed from the outset, in 1971, that the Chairman of the CGIAR should always be a Vice-President (VP) of the Bank, namely the VP in charge of the Bank’s lending for agriculture. Certainly, not everyone of the successive Bank VPs/CG Chairmen personally pushed the social envelope. The big exception was Ismail Serageldin, who became CG’s Chairman in 1993; from his very start, he regularly directed all CG Centers to conduct their work along the principle that “CGIAR’s main clients are people” (Serageldin 1996) (see also Serageldin’s chapter “Social Sciences at the World Bank and the Broadening of the Development Paradigm” in this book).

Once entering in CGIAR, and in an influential position, Michael took a pro-active, militant stand in championing the social science disciplines, sociology and anthropology, searching in every adequate occasion to resource better and expand its assignments of social research projects.

The changes that had occurred even earlier in the CGIAR due to its interaction with the World Bank were also helped by the fact that Cernea and other supporters, mentioned further below, were located in the Bank’s central agricultural department (AGR) which was the part of the World Bank most directly connected to the CGIAR Centers. Thus, this point of departure became the turning point at the CGIAR towards the same direction in which agriculture and general lending of the World Bank were going. A comprehensive reflection of what had happened (Cernea 2016) suggests that efforts and changes in various parts of the development aid process amounted to a “broadening of the economic development paradigm” that reigned in the 1960s and beginning of 1970s at the World Bank and elsewhere towards a more encompassing “social development paradigm”. The impact of this achievement has continued globally ever since, as captured by Cernea (2016).

However, as will be seen in the last section, the flowering of interest in social research in the CGIAR system resulting from the ‘Rocky-Doc’ initiative did not take permanent roots in the entire system. As a result, the CGIAR system remains weak not only in the integration of social research into the mainstream CGIAR work but also in ecological research and knowledge which can only function effectively at the practice level with farmers in the presence of social research on farmer innovation, social organizations, and farmer-driven stewardship initiatives for natural resource management and rural development.

He thus became the first-ever sociologist to receive membership in it in the 20-year existence of CGIAR. Further, from 2000 onwards, Michael became also an active member in TAC’s Standing Panel on Priorities and Strategies (SPPS) led by Alain de Janvry, of which I was the Coordinating Secretary. I worked closely with Michael Cernea throughout his CGIAR tenure on numerous sessions of the TAC and of the SC, and we much intensified our collaboration in 2001–2002 when Michael and I were in charge of preparing and organizing a system-wide conference of the social scientists (non-economists) working in the CGIAR. Michael had initiated that conference by proposing repeatedly its organization until TAC finally agreed. The Conference on Social Research took place at CIAT, in Cali, in 2002, the largest in CGIAR history. Subsequently, I worked with Michael for editing a substantial volume on the status, accomplishments, weaknesses, and future perspectives of social research in the CGIAR (Cernea and Kassam 2006). It remains to date the most comprehensive volume about the history and contribution of sociological and anthropological research to the CGIAR system.

It was not difficult for me to feel sympathetic and in-tune with what Michael Cernea was concerned about in TAC because, despite my different scientific background, his arguments always made eminent sense from an agro-ecological viewpoint. Michael acted on his belief that social researchers’ mission was to produce knowledge usable as an international public good, by, and for, farming communities. I do not believe that TAC had ever experienced anyone like Michael before. He conceived his role in CGIAR as being the lead militant for promoting non-economic social science knowledge as an indispensable component of the broader body of knowledge that had to be generated for the farmers’ world, as the Centre’s scientific products and recommendations. As a consequence, Cernea was deeply concerned about the relevance and effectiveness of CGIAR research in real life, particularly because often CGIAR’s social research, with some exceptions, received little support from cost Centers’ managers, and was often marginalized and chronically underfunded. This was happening despite the fact that the social research that had been carried out in prior years in CGIAR had proven many times its value and indispensability, beyond any doubt. A good number of truly excellent social scientists had joined in earlier years the CGIAR ranks through the “post doc” program financed by the Rockefeller Foundation, and many of them proved their mettle brilliantly by producing insightful research and findings highly relevant to CGIAR objectives. The names of stalwart social anthropologists and sociologists such as Robert Rhoades, Jacqueline Ashby, Ruth Meinzen-Dick, Joachim Voss, Carol Colfer, Pablo Eyzaguirre, Douglas Merrey and some others had written important pages in the annals of CGIAR research. One of them, Joachim Voss, acceded even to the position of Director General for the major CIAT Center, but altogether, despite successes and demonstrated usefulness and usability, social research had been constantly under pressure and gradually squeezed in terms of its institutional position. When the “Rocky-Doc” program stopped, the CGIAR defaulted on its prior commitment to continue expanding and funding more social researchers from its own resources.

From the outset, Cernea developed close links with these and other social researchers, and relied on them and his advocacy and organizational initiatives taken as a member of the TAC or Science Council. This collaboration helped reinforce the cause of social research but the high days of the “Rocky-Doc” program were over, and competition for resources inside the CGIAR was acerbic and the “climate” was not favoring social research expression by any measure. The struggle continued to be an uphill struggle. A key argument was that social research findings should not be seen as just an add-on, but rather as a quality-enhancing intrinsic part of any research and any resulting strategy. We also co-authored a paper on ‘Guarding the Relevance and Quality of Science in the CGIAR’ (Kassam et al. 2004). In it, among others, Cernea argued that CGIAR must put in place a vastly more “biting” and effective ex-ante peer review process of all research proposals to ensure that from the very start of a research project, the social dimensions are incorporated in the research plan and that every new research project is justified by its social and economic relevance to farming communities.

Our typical work pattern in TAC’s 2–3 annual sessions included the analysis of the comprehensive external evaluation reports on scientific research by one or another of the CGIAR Centers. It was quite frequent for Michael to challenge the Director General or Board-Chair of the analyzed Center, for marginalizing social research and underestimating its value. Since certain weaknesses were almost chronic rather than temporary or contextual, sparks were flying quite often. It was difficult to imagine a better-crafted argument in favor of social research than Cernea was able to provide based deeply on his familiarity with agricultural development projects in different countries in which he had worked over the years on behalf of the World Bank. The dominant feature was the constructiveness of his discussion, which invariably offered substance for including in the meetings’ decision recommendations and commitments to expand the scope of social research and the resources allocated to the Center’s social scientists.

His analyses revealed not just passing weaknesses but structural ones in the way research was designed or on the tenure and management over natural resources—water, trees, soil—that were studied by CGIAR’s physical scientists. Michael would often argue that high-yielding varieties cannot succeed if we do not create for them “high-yielding patterns of social organization” through which farmers would get the adequate means required for cultivating them.

The allocation of social researchers to the Center’s key themes was also an object of frequent controversy. Often, Center Directors tended to assign the social scientists excessively to the tail-end of the research process, simply to measure impact, while Michael would argue that their contribution should be incorporated from the very start of the research process so as to factor in farmers’ needs, constraints, and factors like access to credit and markets. Only ex-ante factoring in knowledge on such social values, argued Cernea, could the biological and physical research become germane to the potentials and capabilities of local farming systems and communities.

The Resonance of the CGIAR’s Social Research Conference. An Illuminating Public Discussion

The brief description above, however, elaborates on the structural parameters of Michael Cernea’s work in the CGIAR. However, the most interesting question is: what did he actually do and accomplish? What were Cernea’s views about the status, vocation, the successes and the failures, and mostly the challenges of doing social research within a set of scientific institutions dominated by biological and natural resource scientists as well as economists who claimed to do research on crops, animals, fish, trees, etc. and on natural resource and ecosystem management etc. all in the name of poverty alleviation, food and nutrition security?

The answer is not simple. Summarizing in just a few pages the content of some 8–9 years of work that Michael Cernea invested in CGIAR and in the valedictorian volume he left behind is a hard test. To confront this challenge, I will not follow the chronological path but rather go straight to that interval’s end, when Cernea wrote his summing-up valedictorian assessment of social research in CGIAR. And I take permission to not put forward here only my personal opinions on Cernea’s contributions, but instead rely on a public discussion and assessment by other academics, from outside CGIAR, of Cernea’s leading role and ideas-impact. I can do this because Culture & Agriculture, a specialized journal of the American Anthropological Association, published in its pages the lead chapter that Michael wrote for our jointly-edited volume on social research in CGIAR (Cernea and Kassam 2006) and invited its readership to participate in a public debate of its content.

The “Call to Open Discussion” was signed by the journal’s Chief Editor, Prof. James McDonald (McDonald, 2005). About a dozen scholars sent articles and Culture & Agriculture published them in three issues spanning three years (Fall 2005, vol. 27 no. 2; Spring 2006, vol. 28 no. 1; and Spring 2007, vol. 29, no. 1). A lot of scholars responded promptly: Murray Leaf (Leaf, 2006), Stephen Brush (Brush, 2006), William Loker (Loker, 2006), Ben Wallace (Wallace, 2006), Donald Cleveland (Cleveland, 2006), Jude Fernando (Fernando, 2007), Kendall Thu (Thu, 2006), Lois Stanford (Stanford, 2006), Mina Swaminathan (Swaminathan, 2007). Their comments are particularly relevant also because their authors are prominent social scientists who are independent of CGIAR, as full professors and scholars in various U.S. universities, who observe CGIAR as part of the academic community.

Michael’s study ignited the public discussion because it was an expression of the personal creed of a well-known scholar a true “manifesto” on behalf of social science’s entitlement to solid “citizenship” in the CGIAR. Without mincing words, he protested the fact that social research, despite its indispensability, was nonetheless “a domain that still today has to keep fighting hard for asserting itself against institutional barriers, against scholarly biases from other researchers or some centers’ managers and against virtually constant underfunding.” He documented the innovative contributions of social research to improving farmers’ livelihoods, while also blasting the “major obstacles and institutionalized weaknesses in how social research is being carried out.”

Cernea also postulated another important idea that critiqued the dominant practice in most CGIAR Centers: namely, that social research should not be exclusively a “component” immersed in the vaunted inter-disciplinary research in the CGIAR but must be empowered to also do full-scale stand-alone studies on certain independent social variables of agricultural production and development. He had no hesitation to denounce the “shrinkage of human and financial resources allocated to social research in various centers” on the grounds that “behavioral and social cultural variables of resource management are no less important for sustainability than physical parameters.” “The actual human capacity for social research in the CGIAR system at large and in some centers in particular” he wrote, “is either long-stagnant or has been severely depleted.” He hailed the function of social researchers as “human knowledge conveyer-belts” between the CGIAR and outside scientific research and practice. He also constantly argued for bringing into the CGIAR some of the “important developments taking place in outside research in sociology, anthropology and social geography.” To Michael, CGIAR’s goal of germplasm enhancement, production intensification and natural resources management would not be complete without intensified socio-cultural research that would keep CGIAR’s research programs and strategies relevant to pro-poor development and impact oriented.

Throughout his tenure in the TAC and in the Science Council, Michael Cernea was consistent in taking an exacting analytical position to evaluating the contribution provided by social research to the objectives of each international research center, while at the same time incisively examining the usually scarce support provided by the respective center to social researchers and to integrating the social findings with the finding of biological and natural scientists.

Cernea’s valedictorian study submitted for public discussion was, as usual, provocatively titled, critiquing closed “entrance gates” and claiming the right to recognized status for sociological research: “Rites of Entrances and Rights of Citizenship: The Uphill Battle for Social Research in CGIAR” (Culture & Agriculture, 73–87). He critiqued the obstacles to a broader “entrance” of social research in CGIAR, arguing that the nature of the agricultural process, performed by the widest profession in human history—the profession of farmer—gives social sciences a preeminent and legitimate “right of citizenship” inside CGIAR Centers.

The discussants liked Cernea’s key ideas and conclusions, and embraced the entire book, which in the words of Mina Swaminathan from India,

gives rich and comprehensive image of the heroic contributions of social scientists in the CGIAR over three decades, accomplished against many odds and obstacles. But the book and [Cernea’s] article also paint a dismal picture of the structured institutional constraints and deep-seated intellectual biases against social research in many centers belonging to the international agricultural research system (Mina Swaminathan, 1).

It was no surprise that others joined, in their own words. The breath of fresh air coming out from Cernea’s sharp and candid study was received very well by the scholars outside of the CGIAR, no less than by those inside of it, expressing extraordinary support from CGIAR scholars to his critique and recommendations:

“…Cernea has done the readers of Culture & Agriculture a great service by publishing this piece in our journal”—wrote William Locker, Professor of Anthropology and Dean at the California State University—“And the editors deserve congratulations for inviting debate and discussion on the important topics raised […] in Cernea’s article. Most of us…retain a belief in the power of methodologically sound empirical research as a public good: when deployed intelligently, it has the potential to ameliorate social problems. [This]…bears out the need to focus our intellectual energies on understanding and resolving the social and environmental crises affecting broad swaths of the globe” (William Loker, 17–19).

To this another discussant, Kendall Thu from Northern Illinois University, added:

…The challenges posed by Michael Cernea’s thought-provoking article on social research in CGIAR reflect a broader ongoing challenge in anthropology to make our efforts resonate more widely with a greater impact on policy…My primary theme takes a cue from Michael Cernea’s ontological point that culture has a reality in the everyday lives of agricultural practitioners. My view is that we would do well to turn this around and not just reintegrate culture into agriculture but also integrate agriculture and food systems into broader cultural research, theory, and practice (Kendall Thu, 25–27).

The participants in the public discussion appreciated Cernea’s role in CGIAR in promoting social research, emphasizing the intellectual continuity between what Michael as social scientist militated for and achieved previously at the World Bank and what he undertook to do to change CGIAR patterns as well. Murray J. Leaf, professor of anthropology and political economy at the University of Texas, noted that,

Cernea has been central to the effort of urging the Bank to incorporate more noneconomic social science expertise in the design of projects. He also had a central role in organizing external scholars around themes that the Bank leadership could find intelligible. These primarily revolved around the problem of letting the Bank staff see the projects from the prospective of the intended […] beneficiaries.

Cernea’s article raises concern about the use of social scientists across the entire development spectrum and entails fundamental issues of social theory. Note that Cernea is not calling for just any kind of social theory, but theory that will provide: better understanding of the decision-making process of individuals and groups; identifying the characteristics and needs of the ultimate beneficiaries, poor farmers and poor urban food consumers; the institutional arrangements needed to foster social capital creation; and improved property rights and custodianship regimes and their management and distributional implications. It also should be theory that ‘puts people first’ and facilitates the design of development projects which do so … [We know] what CGIAR could do. What could anthropology do? (Murray Leaf, 11, 14)

Cernea’s robust argument obviously prompted CGIAR’s outsiders to do their own self-questioning about the future of their own research.

Murray Leaf’s “What could anthropologists do?” was further echoed by Kendall Thu:

Cernea’s insights from his experiences in CGIAR raise fundamental questions about the future of agricultural research in anthropology. The challenge Cernea poses transcends agriculture and resonates within our field as a whole. As such, the issue should not be what we can do to increase the viability of social research in agriculture. Rather, I believe our research, methods, and findings will lead the way, but what are the overarching questions and issues we are tackling?

I agree wholeheartedly with poverty reduction as a research goal of CGIAR and anthropologists in general. However, the fact that we face obstacles in becoming systemically effective in policy matters raises the question: why is this and what do we do about it? (Kendall Thu, 25–27)

Ben Wallace, a professor at Southern Methodist University, added to this strand of the debate a mobilizing comment addressed to the world’s anthropological community at large about the overriding responsibility of social scientists to their ultimate “clients”—the people. In a remarkably strong statement, he said:

…In conclusion, the call here is for those of us who work in the field of rural development to remind ourselves occasionally, and others, that while we may work as an anthropologist, a plant pathologist, or an entomologist, and although we are paid by a particular institution, we are fundamentally responsible to the people of the world. If we fail them, we have failed not only ourselves but also those who are most dependent on us for help. Those of us who have chosen to work in the applied environmental sciences have a client—the people of the world. The only way to ensure that our clients are served is to ensure that people remain the central focus of our research and development endeavors (Ben Wallace, 31).

To which Murray Leaf memorably concluded his powerful article with:

To change the place of anthropology in development and in development policy, we have to change anthropology [itself] (Murray Leaf, 16).

Other participants extended the debate to another very relevant area: the insufficient attention to social research in the National Agricultural Research Systems (NARS). Despite the abundance of rural sociologists in developing countries, the NARS did not use their skills within the national research centers. The strongest critique of this situation was formulated by Mina Swaminathan, an advisor of India’s major M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, who wrote that that situation would be “laughable if it were not so tragic.”

…Ignoring the content and methods of social science research has been damaging enough for national research systems, damage many times multiplied in the case of international systems. Just imagine dozens of highly trained and well-equipped scientists, arriving with all sincerity, zeal, and commitment in various parts of the developing world, and attempting to solve their agricultural problems without any understanding of those societies, their structures, and systems! It would be laughable if it weren’t so tragic (Mina Swaminathan, 3).

The above excerpts are only a partial image of the intellectual richness of C&A’s public discussion. This debate showed that Cernea’s analyses resonated with the anthropological profession at large. It also offers a robust platform to the CG management for follow up.

The book ‘Researching the Culture in Agri-Culture’ did not embrace the official rhetoric pretending that all is well with social sciences research in the CGIAR. The CGIAR system would do well to recognize the gaps that persist in its current performance in social science research and take the necessary measures to overcome them. Moreover, many of the substantive issues raised by the above mentioned outside scholars, who are specialists in their topics, and most powerfully by Cernea, are still valid and unaddressed.

His own interest in continuing to write and publish academically the lessons and generalizations he was deriving from his operational development work and field research in many countries had strengthened also his scholarly status.

Concluding Remarks

Today, we have more reasons than ever to drive further the needed paradigm change in agriculture, for both social and ecologically reasons. This applies to the developing world as well as to the industrialized world. Social and ecological research for sustainable production intensification and for environmental stewardship is a reality and must be made to become a greater force for good for all mankind.

Many of us have learned from Michael Cernea that in any human development activity, including those related to agricultural research, the object and the subject must merge and remain united to ensure ‘positive-sum outcomes’ as much as possible. There is indeed much to rethink, learn and teach about the future multi-functional role of agricultural land use which must respect and use the resources of the socio-cultural environment as much as the ecological and economic environment, and to reflect upon past short-comings and achievements. The combat is far from over! For example, for the alternate agro-ecological paradigm involving Conservation Agriculture to spread and replace the old intrusive and narrow out of date Green Revolution paradigm will require, as Cernea has urged, “people who have not only brains but who can fight, people who have not only knowledge but also have conviction, and people whose anthropological knowledge is accompanied by a moral dimension”.

This is Cernea’s challenge to us all—to carry on our work with readiness to engage scientifically and proactively, in the spirit of “militant social scientists”, with farmers and their communities.

Notes

- 1.

The financing of CGIAR’s network of scientific centers is provided by the Governments of developing and industrialized countries, foundations, the World Bank, the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization), the UNDP (United Nations Development Program) and a series of other international and regional organizations. The consortium consists now of 15 International Agricultural Research Centers, which collaborate with hundreds of partner organizations, including national and regional research institutes, civil society organizations, academia, and the private sector (See also footnote 2).

- 2.

The organism that advises on and guides CGIAR’s policies and scientific research work has been initially its TAC (Technical Advisory Committee), then renamed as its Science Council (SC) and recently as its Independent Science and Partnership Council (ISPC); it consists of 10–12 scholars of high international reputation specialized in sciences crucial for CGIAR’s mission. The multidisciplinary research staff of each Center is also multinational. The Centres include: CIMMYT—Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maiz y Trigo; CIP—Centro Internacional de la Papa; ICARDA—International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas; ICRISAT—International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics; IFPRI—International Food Policy Research Institute; IITA—International Institute of Tropical Agriculture; ILRI—International Livestock Research Institute; IRRI—International Rice Research Institute; CIAT—Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical. The new wheat varieties from CIMMYT and rice varieties from IRRI, created after years of extraordinarily painstaking genetic research have triggered the Green Revolution, making possible gigantic increases in agricultural production and productivity.

- 3.

In his country of origin as well, Romania, Cernea had pioneered in the mid-1960s the resumption of empirical field-based rural sociology, helping revive the long and rich tradition of rural sociology in Romania, a discipline that had been for years denied as a “bourgeois science” under the then socialist regime in Romania; his pioneering role in that revival was recognized domestically and internationally. Among other initiatives, Cernea also organized a comparative monographic research on two villages, one of which had been researched and monographed by Romanian sociologists during the 1930s. The book became a landmark: it was the first such comparative research done in Romania and one of the few of this kind produced in the world at large (Cernea et al. 1970).

References

Ashby, J. (1986). Methodology for participation of small farmers in design of on-farm research. Agricultural Administration, 22(1), 1–19.

Bebbington, A. (2006). On Michael Cernea. In D. Simon (Ed.), Fifty key thinkers on development (p. 67). Abingdon, UK: Routledge, Tyler and Francis.

Brush, S. B. (2006). Cernea comment. Culture & Agriculture, 28(1), 1–3.

Cernea, M. M. (1985/1991). Putting people first. Sociological variables in rural development. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cernea, M. M. (2005). Rites of entrance and rights of citizenship: The uphill battle for social research in the CGIAR. Culture & Agriculture, 27(2), 73–87.

Cernea, M. (2016). The state and involuntary resettlement: Reflections on comparing legislation on development-displacement in China and India. In E. Padovani (Ed.), Development-induced displacement in India and China: A comparative look at the burdens of growth. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Cernea, M. M., & Kassam, A. H. (Eds.). (2006). Researching the culture in agriculture: Social research for international development (p. 497). Wallingford: CABI.

Cernea, M. M., & Tepping, B. J. (1977). A system for monitoring and evaluating agricultural extension projects in India. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Cernea, M., Kepes, G., Larionescu, M., et al. (1970). Două Sate: Structuri Sociale si Progres Tehnic [Two villages: Social structures and technical progress] (Under the editorship of H. S. Henri, M. M. Cernea, & G. Kepes). Bucuresti: Editura Politica.

Cernea, M. M., Coulter, J. K., & Russell, J. F. A. (Eds.). (1983). Agricultural extension by training and visit: The Asian experience. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Cleveland, D. A. (2006). What kind of social science does the CGIAR, and the world, need? Culture & Agriculture, 28(1), 4–9.

Conway, G., Adesina, A., Lynam, J., & Mook, J. (2006). The Rockefeller Foundation and social research in agriculture. In M. Cernea & A. Kassam (Eds.), Researching the culture in agriculture: Social research for international development (pp. 373–381). Wallingford: CABI.

Fernando, J, L. (2007). Culture in agriculture vs. capital in agriculture: CGIAR’s challenges to social scientists in culture, Culture in Agriculture, 29(2)

Guggenheim, S. (2006). Roots: Reflections of a “Rocky Doc” on social science in CGIAR. In M. Cernea & A. Kassam (Eds.), Researching the culture in agriculture: Social research for international development (pp. 421–430). Wallingford: CABI.

IRRI. (1981). The role of anthropologists and other social scientists in interdisciplinary teams developing improved food production technology. Los Banos, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute.

Kassam, A., Gregersen, H. M., Fereres, E., Javier, J. Q., Harwood, R. R., de Janvry, A., & Cernea, M. M. (2004). A framework for enhancing and guarding the relevance and quality of science: the case of the CGIAR. Experimental Agriculture, 40, 1–21.

Leaf, M. J. (2006). Michael Cernea’s excerpt: What it means for us. Culture & Agriculture, 28(1), 10–16.

Loker, W. (2006). Comments on Cernea: ‘Keeping agriculture in anthropology’. Culture & Agriculture, 28(1), 17–19.

McDonald, J. H. (2005). Keeping culture in agriculture. Culture & Agriculture, 27(2), 71–72.

Meinzen-Dick, R. (2006). Studying property rights and collective action: A systemwide programme. In M. Cernea & A. Kassam (Eds.), Researching the culture in agriculture: Social research for international development (pp. 285–298). Wallingford: CABI.

Meinzen-Dick, R., & Cernea, M. (1984). Design for water users associations: Organizational characteristics. Environment department. Washington DC: World Bank.

Serageldin, I. (1996, July 22). The challenge for rural sociology in an urbanizing world. Keynote address delivered at the 9th world congress of rural sociology on rural potentials for the global future held in Bucharest, Romania.

Simon, D. (2006). Fifty key thinkers on development. New York: Routledge.

Stanford, L. (2006). Response to Michael Cernea. Culture & Agriculture, 28(1), 20–24.

Swaminathan, M. (2007). Cernea’s thesis: A perspective from the South. Culture & Agriculture, 29(1), 1–5.

Thu, K. (2006). Agriculture in culture. Culture & Agriculture, 28(1), 25–27.

Wallace, B. J. (2006). Keeping people in culture and agriculture. Culture & Agriculture, 28(1), 31–34.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kassam, A. (2021). The Need for Social Research and the Broadening of CGIAR’s Paradigm. In: Koch-Weser, M., Guggenheim, S. (eds) Social Development in the World Bank. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57426-0_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57426-0_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-57425-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-57426-0

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)