Abstract

This chapter explores the obstacles and opportunities that digital entrepreneurs encounter when they operate in developing countries. Drawing on the varieties of institutional systems framework and on three interviews (two digital entrepreneurs and one consultant), this chapter chalks out the idiosyncratic challenges and opportunities for digital entrepreneurs operating in a developing context. Our findings indicate that digital entrepreneurs face a weak institutional infrastructure and an environment characterized by corruption that obstructs their operations. These weak infrastructures result in the inaccessibility to necessary start-up funds, the lack of policies and regulations that protect and support e-commerce, a weak digital infrastructure, and to a deficiency in digitally competent and experienced labor capital. At the same time, our findings indicate some opportunities stemming from the unique institutional setting in which digital entrepreneurs operate. The opportunities translate into the use of family wealth as a source of start-up financial capital, the use of personal connections as a source of social and human capital, and the rising education on digital entrepreneurship and its benefits. We conclude with some suggestions to improve the current institutional infrastructure for digital entrepreneurs in developing countries.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Digital entrepreneurship is defined as the identification and pursuit of entrepreneurial opportunities based on the creation of digital artifacts, platforms, and infrastructures that provide services through technology (Schmidt 2011; Giones and Brem 2017). Digital artifacts consist of applications or any media component that offers a specific function to users (Ekbia 2009; Kallinikos et al. 2013). A digital platform is the collection of a common and shared set of digital artifacts that provide entrepreneurs with a venue for production, marketing, and distribution processes. In the last two decades, digital entrepreneurship has opened new venues for entrepreneurial activities and has transformed the nature of uncertainty inherent to entrepreneurial processes and outcomes (Nambisan 2017).

In a world witnessing continuous and radical innovations, entrepreneurs are developing business ideas that capitalize on the power of technology. Entrepreneurs have the opportunity to offer new products and services to consumers through social media platforms and to use artificial intelligence to measure their impact and reach. Nevertheless, there exists a heterogeneity among digital businesses, where some are entirely tech-dependent (e.g., Web design, e-retail), while others just use digitalization in their marketing and communications operations. In this chapter, we focus on entirely tech-dependent businesses.

Digital start-ups have very low barriers to entry, more porous and fluid boundaries, and do not require costly equipment (Nambisan 2017).They are characterized by flexibility of products or services such that there is no fixed product or service whose features remain constant; rather, product offerings, features, and scope continuously evolve and expand. Furthermore, digital entrepreneurship is no longer restricted to privileged capitalists. Digital entrepreneurs gain access to funding and resources through venture capitalists, crowdfunding, and bank loans (Lingelbach et al. 2005). Crowdsourcing and crowdfunding systems allow the engagement of collective stakeholders in the venture creation process, where entrepreneurs interact with customers, who provide ideas, and with investors that provide capital.

Despite the many opportunities that digital entrepreneurship brings, it has also been linked with high risks of failure given the continuous and radical technological innovations and since the role of employees in a digital business is ambiguous and undefined. Thus, the absence of a mechanic or solid structure makes it more difficult for entrepreneurs to decide and plan a clear operations process that assigns each employee to its corresponding tasks (Brem et al. 2016). The previously mentioned challenges and opportunities for digital entrepreneurship are well documented in the literature, which was mostly conducted in developed countries. However, knowledge about the obstacles and opportunities for digital entrepreneurship in developing countries remains scant.

While the above-mentioned challenges and opportunities to digital entrepreneurship can persist when entrepreneurs operate in developing countries, the embeddedness of a country in a developing context adds additional complexities that may create new challenges and opportunities not usually encountered in developed countries. Indeed, developing contexts are hurdled by the presence of institutional voids, with the state having low law enforcement capacity, and low generalized trust within society (Fainshmidt et al. 2018). Nonetheless, these countries are also characterized by supportive family capital (Samara and Arenas 2017) and sometimes by a high level of knowledge capital, both of which can create opportunities for digital entrepreneurship.

In the following, we first draw on institutional theory and the varieties of institutional systems to describe how the developing context can affect the obstacles and opportunities for digital entrepreneurs. Then, we present two case studies coupled with one expert opinion, to have a closer look on whether the theorized obstacles and opportunities fit with the reality that digital entrepreneurs encounter when they operate in a developing country. While the empirical setting is contextualized in Lebanon; we argue that the findings can be extrapolated to other developing contexts that are subject to similar institutional pressures.

2 Institutional Theory and Varieties of Institutional Systems: Digital Entrepreneurship in a Developing Country Context

Institutional theory emphasizes the role of the social context in determining the behavior of individuals and organizations (Meyer and Rowan 1977). According to institutional theory, individuals are embedded within a social context that has distinct formal and informal rules and regulations that determine the cognitive process through which individuals and organizations behave (Fainshmidt et al. 2018).

In this context, the Varieties of Institutional Systems (VIS) framework has been advanced to discuss how institutions in developing countries may have a distinct impact on individuals and organizations. According to the VIS, there are five institutional dimensions affecting organizational behavior in developing countries: The role of the state, the role of financial markets, the role of corporate governance institutions, the role of human capital, and the role of social capital (Fainshmidt et al. 2018).

In developing countries, institutional voids, which are defined as weak or non-functioning market mechanisms (Jamali et al. 2017), are prevalent. While these voids may lead to challenges for digital entrepreneurs, they may also open new opportunities. Using the VIS framework, we are able to classify institutional voids into internal factors, which are part of the microenvironment, and external factors, which are part of the macroenvironment. Internal institutional voids of a business include human capital, along with their exposure to Information and Communications Technology (ICT) skills, their level of technological awareness, skill-based resources, financial status, and perceptions and attitudes toward society and technology. The external institutional voids include the government, market e-readiness, level of trust in society, the financial market, and supporting industries e-readiness. Despite the fact that successful online venturing is associated with the preceding institutional elements, material and cultural aspects are essential to account for when discussing the success or failure of digital entrepreneurial ventures.

The State can influence the economy through its direct and indirect interventions in the market and through the diverse forms that it can take. There can be four types of states: Welfare State, Developmental State, Predatory State, and Regulatory State, the latter being the state that sets and enforces rules, thus, directly impacting economic activity (Rosecrance 1996). A Welfare State protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, mainly through the redistribution of wealth by the government. A Developmental State is concerned with engaging in advancement of business sectors through industrial policy. Within a Developmental State, governments strategically monitor and facilitate business activities, transactions, and e-commerce initiatives. If present, developmental states can develop the needed infrastructure for the reinforcement of new digital infrastructure, hence allowing the necessary ground for entrepreneurs to share and edit their ideas in the process of opportunity formation. Unfortunately, development states are scarcely found in developing countries, where, more often than not, Predatory States dominate. Predatory States are known for being elites who monopolize power through the absence of market competition, discreet decision-making processes, and weak institutional supportive capacity, which translates into the state withdrawing from any activity that can assist, organize, and protect digital entrepreneurs (Carney and Witt 2012).

Financial markets are the core element of institutional systems as they acquire and distribute capital (Davis and Marquis 2005). Developing economies tend to substitute financial markets with internal capital markets, usually based on accumulated family wealth (Steier 2009); thus, limiting in part the growth of businesses as family capital is considered as a finite source. Financial resources play a critical role in digital entrepreneurship. Although online ventures require lower entry cost than that of a bricks-and-mortar business, the lack of financial resources present significant challenges, specifically to those belonging to lower socioeconomic social class.

Corporate governance relates to how companies are managed and controlled. In developing countries, ownership of companies is concentrated within family hands (Khanna and Palepu 1997; La Porta et al. 2000). Therefore, ownership concentration affects how owners, labor, and management interact with each other. The existence of wealthy families is well noted in the Middle East, Latin America, Northern Africa, and Asia. This leads to family firms being the predominant organizational, and the latter are not only concerned with financial returns, but also with nonfinancial benefits such as the family’s identity and preserving family influence in the business (Samara and Paul 2019). In the context of digital entrepreneurship, corporate governance levels refer to the extent to which top management leads and organizes a business through incorporating technology and e-commerce ideas and projects. Creating a family supportive environment in which corporate digital entrepreneurship can thrive therefore becomes a double-edged sword. On one hand, digital entrepreneurs may have easy access to family wealth to pursue their entrepreneurial endeavors, but on the other hand they may be faced with family seniors that are reluctant to fund such unknown and uncertain entrepreneurial paths.

The fourth aspect of the VIS taxonomy includes the formation of knowledge and skill within an institutional context and how labor is organized. Labor relations are essential to optimizing human capital and predict whether or not employees in organizations will have the necessary knowledge and skills to engage in strategic activities. More fragmented labor markets result in higher employee turnover rate and flexibility, thus making labor less efficient and effective and shifting the organizing principle to political and/or family connection-based foundations (Aguilera and Jackson 2014). Furthermore, technical knowledge is considered as human capital resource. Particularly in the developing context, acquiring knowledge on digital selling tools and technologies is necessary in developing an online presence and effective communication with Web site developers, industry professionals, and tech-support providers. The level of technical knowledge and resources acquired can be contingent on the availability of a qualified workforce capable of providing digital businesses with the required human capital support. Furthermore, the level of knowledge capital within a nation determines how productively organizations engage with employees. For instance, the availability of knowledge capital in companies allows organizations to invest in firm-specific skills (Jackson and Deeg 2008), while scarcity in knowledge capital may reduce incentives to invest in specific sectors or competencies. In this context, the scarcity of certified and highly skilled ICT specialists might be attributed to the high cost of recruiting and retaining them. Subsequently, the availability of employees with adequate experience and exposure to ICT skills required to successfully undertake e-commerce projects indicates the formation of entrepreneurial prospects. This means that entrepreneurs in developing countries might have to incur the additional cost of recruiting expert-level employees. The low level of ICT awareness among staff members refers to the low level of awareness of e-commerce potential, which could be due to the lack of long-term strategic planning. Moreover, small businesses may not benefit from ICTs due to their lack of knowledge, skills, and resources necessary to excel in the world of digital entrepreneurship. The adequacy of ICT skills such as the number of local content creators and communication and software engineers is an important factor in the level of adoption of technology in entrepreneurship. Furthermore, the adequacy of technical support also plays a role in determining the level of technological incorporation.

From a cultural perspective, in developing countries, societal perspectives on gender play an important role in the credibility and validation of women’s resources, which create disadvantages to their entrepreneurial success. Even in the digital workspace and in terms of professional qualification, women face sexism and hostility. There is a disadvantaged stereotype about femininity and beliefs about technological competence (Kelan 2009). Other views on race and social class demonstrate how in advanced Western countries, white elite and upper middle-class males dominate positions of power; so, whiteness and masculinity form the “ideal” entrepreneurial type and consider to be intangible resources to entrepreneurial legitimacy (Ahl 2006).

The role of social capital refers to the degree to which members of society trust other members, also known as the level of generalized trust (Inglehart 1999; Putnam 1993). Prior studies have shown that trust plays an important role in a country’s economic activity (Knack and Keefer 1997). The lack of generalized trust implies that individuals and organizations depend on informal networks that are centered on more specific trust, such as family ties. When applied to digital entrepreneurship, market e-readiness refers to the company’s, customers’ and suppliers’ willingness to conduct business electronically. Supporting industries e-readiness consists of the assessment of the development level and cost of support-giving institutions such as IT, telecommunications, and financial ones, whose activities might influence e-commerce adoption and initiatives in developing countries. Hence, trusting a business partner through an e-platform may be a significant factor affecting digital entrepreneurship in developing countries. For example, given that the level of corruption in developing countries is high, people often question whether a business is reliable, safe to deal with, or will accomplish the task given at hand. Trust is built upon “long-term experience of social organization, anchored in historical and cultural experiences.” (Rothstein and Stolle 2008, p. 311). This especially applies to developing economies, where corruption is prevalent and has consequences on the trust of the government, in business, and in society. Prior studies have found discrepancies in the level of trust and corruption in developing economies. From the digital entrepreneurship perspective, instead of being a neutral space where all stereotypes differences, or labels are eradicated, the online environment shows to be reflecting social inequalities among aspiring entrepreneurs. Therefore, citizens might find it difficult to trust the validity and fairness of systems in society. Additionally, the importance of social and human capital gathered in previous higher status employment challenges the idea that just about “anyone” can start a credible online business with minimal investment.

3 Cases and Expert Opinion

Below, we present two cases and an expert opinion, which exemplify how embeddedness in a developing context affects the obstacles and opportunities encountered by digital entrepreneurs. The expert opinion provides a wider perspective as our expert has more than ten years of experience working with digital entrepreneurs across the Middle East. Furthermore, the two cases, that we purposefully choose, exhibit the situation of a large business as well as a small business. This allows to show a holistic perspective on the various challenges and opportunities that digital entrepreneurs can face when operating in developing contexts.

3.1 Expert Opinion

We interviewed Dr. Diala Kabbara, a Lebanese emigrant who works in Italy as a consultant for some local and Middle-Eastern companies and is a professor of Entrepreneurship in University of Pavia, Italy. Dr. Kabbara shared her insight and expert opinion via Skype, during the course of an hour-long interview.

According to Dr. Diala., a primary driver to opening any online store is creating a high-value proposition that is customer-oriented targets to solve problems that customers face and eases their pain points.

-

1.

Role of the “3F”s:

Dr. Diala highlights the opportunities that digital entrepreneurs have through capitalizing on the “3F”s: family, friends, and funds. Family and friends are considered as social and/or human capital, and funding includes raising money through crowdfunding, which is exposing one’s innovative idea to the public and getting supported financially. Another way to get funded is through creating relationships with accelerators and incubators.

It is crucial for digital entrepreneurs to have capital for their start-ups. Dr. Diala speaks about the importance of financial markets in digital entrepreneurship and introduces the term financial “bootstrapping,” which refers to, “launching new ventures with modest personal funds” (Winborg and Landström 2001, p. 235), and satisfying the need for resources without depending on debt or external finances (Smith 2009). Financial bootstrapping techniques are essential for business start-ups, particularly tech-based ones, and include making deals with customers, borrowing from suppliers, low-cost labor, and creating special relationships with individuals and organizations (Smith 2009).

A challenge of digital entrepreneurship in developing countries is funding. In developed countries, you may have a lot of grants to fund businesses. Here, we can refer to the role of the state. The state can either be a barrier to digital entrepreneurship by imposing heavy regulations and bureaucracy, or a supporter, by providing financial support. The government could financially support a specific age or gender group. For instance, in developed countries, the state can hold events and competitions for a specific age or gender group (e.g., female entrepreneurs under the age of 30), where a selected applicant gets funded by the government.

-

2.

Customer Expectations:

Customers in developing countries are accustomed to purchasing items in physical stores, having the experience of trying things on, and using their senses. Virtual purchasing is still a somewhat foreign concept, contrary to that prevalent in developed countries. This could be due to cultural differences nested therein. Developed countries tend to value “the hustle and the grind” and can’t afford to waste time or effort. So, it’s easier and quicker for them to purchase things online, whereas in less individualistic countries or developing counties, people don’t mind and might even be excited to do things the “physical way.”

Internet issues pose challenges to digital entrepreneurship in developing countries. For example, Internet fees in Lebanon are very high compared to that in other developed countries. Dr. Diala says, “in Italy, Wi-Fi is even sometimes free in parks, whereas in Lebanon, Internet is expensive and very slow.”

Cultural differences among target audiences can play a role in expanding an online company to other regions. As our interviewee mentions, “you can’t just scale your online business to another country in the Middle East. Maybe an app in Lebanon may not be accepted in the gulf area.”

In addition to these challenges, in developed countries, the types of industries are wide and diversified, whereas in developing counties, industries are narrower and more limited to specific sectors.

-

3.

Network Opportunities:

A network can have two dimensions: personal and professional. Personal links such as family and friends can spread awareness and share one’s business through media. Professional connections are crucial, especially in digital entrepreneurship, for they can also provide mutual benefit for both parties. As Dr. Diala mentions, “personal connections are important for creating partnerships with other companies in the future, such as alliances or collaborations.” Dr. Diala mentions, “personal connections determine the quantity of people in a network, and social capital determines the quality and variety of your connections.” Personal connections can also count as human capital and/or a source of knowledge. Dr. Diala says, “if some of your personal connections have had experience in digital entrepreneurship, then they can give you valuable and useful insight, and share their experiences with you.”

The family plays a role in digital entrepreneurship, for it provides financial support, as well as moral support like trust. Families can tolerate and support the trials of their next of kin despite the risk. The family could help in idea generation and may provide consultation in various matters. Dr. Diala mentions, “the family could play an even more important role if a member in the family has had experience in the field of digital entrepreneurship.” Families can also pave the way for various networking opportunities.

Increasing one’s social capital, being the number of network relationships among people who live and work in society, is crucial for the success of a digital company. That means it is preferable to diversify one’s networks, for instance, by making personal connections in different professional fields to gather a variety of suggestions and ideas. Dr. Diala says, “the more networks you have, the more the possibility to get funded.”

-

4.

Rise of Tech Devices:

Dr. Diala pointed out an opportunity in the digital industry, being the rise in the number of tech-device (smartphones, computers, etc.) users. Students are being educated on the use of technology, and it is observable that the younger generations avidly use their smart devices.

-

5.

Syndicate and Lack of Human Capital as Challenges:

Dr. Diala discusses the role of syndicates by suggesting that syndicates are not as necessary for freelance jobs such as digital entrepreneurship as it is for other fields. She says, “for digital entrepreneurship, syndicates would mainly be used to share risk, or to provide funds for digital entrepreneurs, and for security or insurance.”

Another challenge might be the lack of competent, digitally skilled, and experienced labor capital. According to Dr. Diala, employees should have a set of specific digital skills, competencies and knowledge, such as skills in SEM (search engine marketing), content marketing, social media marketing, and social selling. As Dr. Diala says, “if you don’t have these skills, you may not be the right person to go into digital entrepreneurship.” For recruitment, it is preferable to recruit technologically competent people, rather than only entrepreneurially competent or “business-minded” people. Thus, education is crucial for this matter. The sources of education could be the information and skills acquired during higher degree education, such as courses on data analysis, artificial intelligence (AI), e-computing, digital entrepreneurship, or through paying for online learning, tutorials, and software.

3.2 Case Studies

3.2.1 LebMall Start-up

We interviewed the founder of a start-up called LebMall.com, John (the name of the company and the interviewee has been changed to ensure anonymity). LebMall.com is an e-commerce, multi-vendor Web site that offers brands a platform to sell their items and make commission off of sales. LebMall company has twelve employees that can support up to 1000 orders per day. In addition, LebMall.com offers shipping of its products. In the founder’s terms, it’s like the “mini-Amazon” of Lebanon. LebMall.com management is currently focusing on the growth of two departments, which are those of electronics and apparel.

-

1.

John’s Vision:

The main driver behind starting this digital enterprise was the founder’s and his family’s search to start a new project that would satisfy the market demands and gaps in the market. John says, “it all started when I witnessed the crisis of brick-and-mortar clothing stores in Jounieh,” the city where John was raised, where shops were shutting down. “It is true that there is an economic crisis in Lebanon, in real estate and in big companies, but this crisis can’t be applied on clothes since the demand for apparel is a constant.” He adds, “stores in malls are also closing, not because people stopped buying clothes, but because people are purchasing them through online platforms such as Aliexpress.com.” John elaborates by saying, “one day, my family and I had gathered for a family meeting, where we concluded that the Lebanese economic situation had been declining, negatively impacting our real estate business.” Thus, leaving their real estate business on hold, John and his family decided to come up with a new business venture. John suggested e-commerce, and the family board agreed.

-

2.

Personal Connections/Family as Opportunities:

Personal connections can be considered as part of social capital and can serve digital entrepreneurs during their journey. John ardently emphasizes the role of his personal connections in the process of setting up his business. He says, “had it not been for my personal connections, I wouldn’t have the number of vendors that my business has, nor would I have been able to equip relatively fast Wi-Fi to LebMall as quickly as I did, through the help of my connections. It would’ve taken me a year.” His family’s reputation played an essential role in building those connections and on capitalizing on old connections. Therefore, John’s privileged position provided him with sufficient preceding social and financial resources that overcome knowledge limitations to develop his entrepreneurial ideas.

Family can be regarded as a source of both social and financial capital. The level of trust among family members, as well as their moral and financial support, benefits digital entrepreneurs. Family wealth provides advantages in the launch of any type of business. For instance, John attributes the launch of LebMall.com to his family’s tremendous support with financial resources. John mentions that the basis of his family profession is real estate. His family enterprise provided the necessary capital to launch LebMall.com; hence, he did not need to search for funding. He says, “if it weren’t for my family’s enterprise, LebMall would’ve shut down by the end of the first day.”

-

3.

Weak Institutional Infrastructure as a Challenge:

John emphasized the weak institutional infrastructure of Lebanon, which leaves the digital entrepreneur unprotected. In Lebanon, there isn’t a law or database that protects e-commerce. John says, “for example, if I lose my password, there is no backup.” Nobody can complain about the mishaps or errors that occur in the online world in Lebanon. Additionally, there is a lack of protection for consumers in e-commerce. He says, “if you receive a broken or malfunctioning product, there is nothing you can do about it.” As a result of the absence of law for digital entrepreneurship, there isn’t a syndicate for e-commerce in Lebanon. This absence indicates that there are no forces that can instill pressure on the government for the declaration of the rights of digital entrepreneurs, such as protection laws or services.

The founder was not hesitant to express the challenges he had faced along his process of launching LebMall. He states that these challenges range from cultural differences to a lack of an online payment system and the deficiency in digital infrastructures for online business transactions. John says, “in developed countries such as the U.S., vendors communicate and sign contracts with the e-commerce platforms via email, whereas in Lebanon, I have to prepare a hard copy version of the contract with a customer. This consists of a lengthy process of going to lawyers, making the contract official, and giving them commission; thus, increasing the probability of customers backing out of their online purchase.” He continues by saying, “the stock in Lebanon is not electronic and it’s not easy for someone to prepare a feasibility study for investors to invest in or fund online businesses.”

John states that the Lebanese bank has prohibited PayPal (the most popular online payment and monetary transaction system), and that the only payment system available in Lebanon is “Ariba,” which takes 3% commission on each transaction, when it should only be taking 0.5%, again hinting at corruption disrupting business affairs.

Another difference that John states is that the concept of “e-signature” is not acknowledged in Lebanon: “we send contracts by PDF and ask our vendors to print it out and send it to us by Aramex. So, whereas others do this in a minute, this process takes us two weeks.” John adds, “in other countries, it is very simple and easy for anyone to upload a product they want to sell online, whereas, in Lebanon this process is more complicated and time-consuming.” In addition, John pays $2000 per month for Wi-Fi, whereas in developed countries, the price of even faster Wi-Fi is $50 per month.

Despite all the disadvantages that digital entrepreneurs face in Lebanon, the founder still wants to make a business footprint in his country: “to begin with, Lebanon is my home. Secondly, in developed countries such as the USA, there exists a lot of monopoly and competitors in e-commerce, like Amazon.com. So, launching LebMall.com in Lebanon gave me an advantage of being a first mover.”

John elaborates by saying, “Lebanese citizens consider the price of their online shopping items expensive since they aren’t accustomed to paying a large amount of money online; however, little do they know that they already spend its equivalent sum in daily activities or expenditures such as fuel and groceries.” He states that Lebanese citizens aren’t well informed about e-commerce and digital entrepreneurship isn’t well integrated in the Lebanese culture.

The founder also states that LebMall.com has been facing challenges in the apparel department. LebMall.com imports clothes for women in containers from Turkey. During the importing process, they pay shipping taxes on these containers from Turkey to Lebanon, as opposed to people who bring clothes from Turkey in vans or suitcases without paying taxes.

-

4.

Competition as a Challenge:

John expresses that the biggest problem that e-commerce, specifically his company, faces is the competition that imposter stores set by selling knock-off products and fooling customers.

LebMall.com wouldn’t be settled in Lebanon if it’s not registered in the ministry of economy. John says, “every picture owned by the business has to be registered for copyright; regardless, these pictures are being “stolen” and copied by other stores.”

John brought and installed Internet servers from abroad called “Cloudflare” into LebMall.com, which costed him $2000 per month since he realized that with Lebanon’s relatively slow internet, customers won’t wait more than twenty seconds to press a button and place an order online. Additionally, the financial sector in Lebanon poses a threat to John’s online business through imposing high bank interest rates.

Due to weak institutional structures and the prevalence of corruption, people in Lebanon are often not propelled/compelled to properly follow procedures. So, to get things done as efficiently as possible, John likes to keep people motivated by engaging in gift-giving to those who assist him. This can be considered as an additional cost to the business.

-

5.

Human Capital as an Asset:

With respect to the role of human capital, the founder emphasizes on the efforts he and his team have been making to study the Lebanese market and grow the business. For example, they conducted feasibility studies regarding the success of LebMall.com prior to its launch.

This is an indication of his individual drive that led him to train himself. He says, “I know how to develop Web sites through my personal education and curiosity.” The founder demonstrated signs of passion for entrepreneurship, determination, will to succeed, and a strive for knowledge and growth during his interview. John, as well as other entrepreneurs operating in developing countries must be willing to take risks, be able to bounce back from failure, and have thorough knowledge of the market and its demands. They must step out of their comfort zones and push themselves to improve their skill-set to attract their customers’ attention and engagement. John stated that he’s eager to learn, and as a compensation for the low levels of knowledge capital, he and his team are ready to go out of their way to learn further and excel in this endeavor.

Digital entrepreneurs have different approaches and intentions for each of their businesses. For instance, John expanded his company within several industries (electronics, apparel, etc.) with LebMall.com, since he had the capital to do so, whereas below entails how Lynn, the founder of WIB.com (WIB stands for “Women in Business”), targeted a specific industry (beauty industry), having a more limited capital. In addition, John communicated with his costumers solely in the digital space, whereas Lynn, other than using social media and online tools to advertise, adopted a technique dependent on human contact and face-to-face interaction with her customers.

3.2.2 WIB Start-up

We interviewed the founder of WIB.com (WIB stands for “Women In Business”) Lynn (the name of the company and the interviewee have been changed to ensure anonymity). WIB.com is an online beauty and health shop. Lynn is a young entrepreneur, who started by selling and managing a single makeup brand, which was the official provider of an original makeup brand in Lebanon. She later decided on incorporating a variety of beauty and skin care brands, and health and fitness items, expanding it into WIB.com.

-

1.

Lynn’s Vision:

Lynn’s vision was selling good-quality makeup at very fair and reasonable prices compared to other makeup brands. She says that she’s been working on the main beauty brand in WIB.com for two years. She spent this time positioning and advertising the brand, in addition to testing the waters with her overseas supplier to make sure she could trust them. Therefore, WIB.com started as a small-scale business at first, but after gathering feedback from customers regarding the quality and the packaging of the products, Lynn has been rapidly growing her business. The founder points out that she associated her drive for starting and succeeding at her venture with the concept of self-actualization, which is “end-goal” in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Self-actualization includes personal development and satisfying one’s inner needs of achievement. She says, “as a woman in the Middle East, I am achieving something and contributing to society.”

-

2.

Role of Education:

With respect to her education, Lynn has a bachelor’s degree in marketing and is currently finishing up her master’s degree in finance. The university she received her higher education from did not offer any courses on digital entrepreneurship. Lynn, not having a business background, was motivated to start her online shop by being influenced by her friend who is an entrepreneur and also hadn’t studied business. Hence, Lynn participated in workshops and received certificates on online marketing (e.g., the tools to use to promote a brand on social media). Lynn’s marketing degree helped in marketing the brand and her store. Additionally, Lynn taught herself some necessary entrepreneurial and technical skills by watching videos and tutorials on online shopping and trend marketing.

-

3.

Role of Social Capital:

Lynn’s family was very supportive of her decision to start a business: “my family has always supported me in everything I do that they deem feasible.”

In addition to her family’s moral support, Lynn’s family ties provided her with an opportunity to expose her business to the public. At a dancing event organized and hosted by her brother, where most of her dance students and friends had attended, Lynn found and used the opportunity to promote and sell her brand. During the event, Lynn sold makeup products at a stand near the entrance, where everyone who walked in was introduced to the what WIB has to offer, along with its quality level and price ranges.

Lynn states that, “personal connections really help in Lebanon; that’s just how the way things work here. If you need something, you refer to someone.” She gives the example of the time when she needed and was in search for a delivery agency for her business. One of her acquaintances had worked with a particular delivery agency and recommended them to her; so, she didn’t face any hesitation in choosing, trusting, and working with this agency.

Moreover, Lynn’s close friends supported her and offered various ideas and suggestions regarding her business.

Our interview with Lynn hinted at an important link between social and human capital. The social capital, including personal connections, can serve to form a company’s human capital. This is the case with Lynn, as her friends and herself make up WIB’s team. When asked about her employees, the founder states that she doesn’t refer to them as employees, but rather as members of a team comprised of herself, an editor who is responsible for graphic design and Photoshop, an entrepreneur who also has a cinematography (photography and videography) background, a person responsible for customer support, and another for answering messages on social media. This small team built her Web site and keeps track of inventory. All members of the team constantly work on developing and expanding their skill-set.

In addition to Lynn’s personal connections contributing to the company’s human capital, they ended up being a big part of the clientele and supporters of her online shop. Lynn says, “in Lebanon, everything is based on Public Relations.” When Lynn first introduced WIB to her friends, family, students, and other acquaintances, they weren’t reluctant to purchase its products, for they trusted that she wouldn’t sell and promote an arbitrary brand of bad quality; thus, they weren’t dubious of it being a rip-off due to her good relationships with students and friends and assumed the brand to be of good quality.

Thus, Lynn’s asset was her social capital and the trust that comes with it. She gained a lot of customers through her friends, students, and other personal connections. Due to their trust in Lynn and her assessment of quality and standards, many ended up purchasing products to try them out. As she says, “because they know me and trust me, they trusted the brand.” So, upon hearing Lynn being associated with the brand, more people were inclined to try out the brand, but this really only goes so far as a “first impression.”

Hence, according to Lynn, the key to creating long-lasting customer relationships, maintaining customers’ trust, and having loyal customers is not only to consistently deliver of-value products and show them their quality level, design, and packaging, but also to provide them with after-sale services such as customer support and delivery.

The founder points out that for her, “it’s also a matter of self-satisfaction or self-esteem.” If people were to be dissatisfied with the products and started giving bad reviews or feedback, not only would people lose trust in the brand but also in her judgment. She tries to avoid disappointing people’s expectations of anything she promotes and sells for this would affect her self-esteem as an entrepreneur. She says, “that’s why I took the time to really work on this brand.”

During the process of building customer-brand trust, a crucial step is to be able to experience a product “hands on”; thus, customers use their senses to assess quality. Lynn says, “in the online world, and especially in the makeup business, customers want to see, smell, and touch the product for themselves.” Another challenge for Lynn has been the willingness of customers to pay delivery fees. She expresses that due to Lebanon’s unemployment crisis, weak economy, and corruption, citizens tend to find delivery charges inconvenient (She charges $5 for delivery and free delivery if a purchase exceeds $75). Lynn mentions that a challenge she faced at the start was her lack of contacts and know-how to go about things.

-

4.

Role of Weak Digital Infrastructure and Risk:

According to Lynn, the payment process has caused her some hurdles: “in Lebanon, it’s very difficult to have online money transactions like PayPal; so, I’m using a cash-on delivery system, which slows the process.”

Lynn also expresses that as some parts of her entrepreneurial journey got easier, such as getting accustomed to the process of it all (logistics, new-item negotiation, delivery, relationship with supplier, etc.), other areas like customer satisfaction got more challenging, for she had to perform analysis on customer demand.

When it comes to risk management, Lynn says that at first, the risks facing the success of her business were high, but they decreased since she started selling in small quantities, which come with low cost of loss. Moreover, Lebanon has a weak infrastructure and is continuously hurdled with uncertainty and disruption. All of these are obstacles to Lebanese citizens’ creativity because they are too preoccupied with such problems that restrict them from devoting their mental energy to innovate ideas and from tackling their creative sides. As Lynn further explains, “an observation for this could be that that Lebanese citizens who immigrate to another country end up being entrepreneurs or innovators and excel in their fields.” Moreover, there aren’t any bank-loan offers for entrepreneurs to start their business and borrow money from banks as their initial capital. Lynn says, “banks don’t support entrepreneurs or digital entrepreneurs. And even if some do, they have really high interest rates. So, it’s basically just advertising. Nothing more.”

Despite the mentioned impedances, Lynn states that an online business is portable: “the advantage of having an online business is that it can be run from anywhere around the world; so, when I travel, I can take the Web site and online shop with me and simply change my target market and/or language.”

-

5.

Role of Financial Capital:

Lynn said that she saved up a bit to gather the necessary financial capital. Furthermore, she states that she didn’t need a lot of money as investment for she found that with her digital business, the majority of her costs weren’t monetary, rather, they were the time and effort she devoted to grow her store. The founder says that it’s much cheaper for one to open an online shop than a brick-and-mortar store, to save oneself from the additional costs it incurs, such as rent and electricity bills.

-

6.

Social Issues:

The terms “young” and “female” are certainly not the standard and typical notions that come to Lebanese citizens’ minds when they think of entrepreneurship. Lynn finds it puzzling that the Lebanese don’t find being accomplished at a relatively young age usual or normal.

Moreover, gender discrimination is an issue that forms a barrier to women’s success in digital entrepreneurship. Lebanon, though can be regarded as a modern country, is still part of the Middle East, where traditional male-dominating mindsets and societies are prevalent. People view women’s work as an “attempt,” rather than legitimate, added value to society, and this could be demotivating for female entrepreneurs. Lynn says, “in some aspect, I can still sense that because I’m a woman, since whatever I do, people will still think my job is less competent than that of men’s. Nevertheless, I’m glad that my team and I are still achieving something.” Furthermore, Lynn says, “obviously, I feel a sense of achievement, being a 24-year-old entrepreneur, but people often get shocked when I tell them about my career and academic path, considering my young age.”

4 Discussion and Conclusion

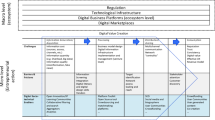

We started this chapter by highlighting that we know little about the obstacles and opportunities encountered by digital entrepreneurs embedded in developing countries. Through our study, we unpack these obstacles and opportunities and we present a comprehensive framework highlighting them (see Table 1).

As shown in Table 1, digital entrepreneurs encounter a variety of challenges when operating in developing countries. These challenges include a deficit in funding, lack of policies and regulations that protect and support e-commerce and digital entrepreneurs, deficiency in digitally competent and experienced labor capital, lack of adequate online payment systems, and cultural differences among target audiences. Digital entrepreneurs in developing countries face the challenge of inaccessibility to the necessary funds, due to the scarcity of venture capital markets and “business angels.” The state hasn’t established laws that provide security for digital entrepreneurs. Syndicates organizing the work of digital entrepreneurs are absent and digital entrepreneurs are left to gather financial resources through crowdfunding, investors, or through family supported funds. The main obstacles for the success of digital entrepreneurship in developing countries are the lack of digital competence, the lack of adequate skills of the workforce, and the lack of information about appropriate laws and regulations. Therefore, recruiting the right human capital with the right skill-set, background and education (self-teaching or university courses) is essential. Another challenge is the absence of online payment systems, which causes issues during delivery of products. Cultural differences among areas of consumer behavior and societal norms are obstacles to the growth and expansion of digital companies in various developing countries. Lebanon’s weak digital infrastructure, slow Internet, and limited industry are all barriers to digital entrepreneurship. Another challenge is the absence of online payment systems, which causes issues during delivery of products for the success of an online business. Therefore, recruiting the right human capital with the right skill-set, background and education (self-teaching or university courses) is essential. Cultural differences among areas are obstacles to the growth and expansion of digital companies in various developing countries. Lebanon’s weak digital infrastructure, slow Internet, and limited industry are all barriers to digital entrepreneurship. In addition, as seen in the first case study, high tax rates on importing goods create resistance among digital entrepreneurs to import and in turn to sell their products.

The opportunities of digital entrepreneurship in developing countries include family and personal connections as a source of social, human, and financial capital. Other prospects include an increase in the users of digital devices and excelling in digital entrepreneurship in Lebanon through selling niche products via online stores, for they are high in demand. Furthermore, starting up a digital business in developing countries, where online businesses are scarce provides digital entrepreneurs with the first-mover advantage, as opposed to in developed countries, where there exists a lot of monopoly and high competition in the e-commerce industry (such as Amazon.com).

The two case studies and expert opinion indicate that digital entrepreneurship is a relatively novel concept in developing countries such as Lebanon and requires further development. Digital entrepreneurship requires a variety of competencies and skills, ranging from technical, financial, and managerial to risk-taking, and having an entrepreneurial and innovative culture. Therefore, we suggest that the state needs to mandate more protective laws to digital entrepreneurs and fill the digital skills gap, through education on digital entrepreneurship (technical skills, online marketing, etc.)

To overcome the digital infrastructure through, digital entrepreneurs could spot areas where the Internet is relatively faster and base their businesses around those areas, or pay an additional amount for instilling faster Internet, such as 5G Internet infrastructure. Another challenge is the lack of an adequate legal infrastructure that allows, for example, for an “e-signature,” where entrepreneurs have to deal with a time-consuming process of printing, scanning, and faxing. In addition, digital entrepreneurs would benefit from getting funded through both public and private sectors to finance risky, early-stage ventures, and ensure persistence and continuity of funding to these technological projects (Fig. 1).

References

Aguilera, R. V., & Jackson, G. (2003). The cross-national diversity of corporate governance: Dimensions and determinants. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 447–465.

Ahl, H. (2006). Why research on women entrepreneurs needs new directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 595–621.

Brem, A., Maier, M., & Wimschneider, C. (2016). Competitive advantage through innovation: the case of Nespresso. European Journal of Innovation Management, 19(1), 133–148.

Davis, G. F., & Marquis, C. (2005). Prospects for organization theory in the early twenty-first century: Institutional fields and mechanisms. Organization Science, 16(4), 332–343.

Ekbia, H. R. (2009). Digital artifacts as quasi-objects: Qualification, mediation, and materiality. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(12), 2554–2566.

Fainshmidt, S., Judge, W. Q., Aguilera, R. V., & Smith, A. (2018). Varieties of institutional systems: A contextual taxonomy of understudied countries. Journal of World Business, 53(3), 307–322.

Giones, F., & Brem, A. (2017). Digital technology entrepreneurship: A definition and research agenda.

Inglehart, R. (1999). Trust, Well-being and Democracy. In M. E. Warren (Ed.), Democracy and Trust (pp. 88–120). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jackson, G., & Deeg, R. (2008). Comparing capitalisms: Understanding institutional diversity and its implications for international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(4), 540–561.

Jamali, D., Karam, C., Yin, J., & Soundararajan, V. (2017). CSR logics in developing countries: Translation, adaptation and stalled development. Journal of World Business, 52(3), 343–359.

Kallinikos, J., Aaltonen, A., & Marton, A. (2013). The ambivalent ontology of digital artifacts. Mis Quarterly, 357–370.

Kelan, E. (2009). Performing gender at work. Houndmills: Palgrave-MacMillan.

Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. (1997). Why focused strategies may be wrong for emerging markets. Harvard Business Review, 75, 41–54.

Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1251–1288.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (2000). Investor protection and corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(1–2), 3–27.

Lingelbach, D. C., De La Vina, L., & Asel, P. (2005). What’s distinctive about growth-oriented entrepreneurship in developing countries? UTSA College of Business Center for Global Entrepreneurship Working Paper (1).

Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American journal of sociology, 83(2), 340–363.

Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 1029–1055.

Putnam, R. D. (1993). The prosperous community: Social capi- tal and public life. American Prospect, 13, 35–42.

Rosecrance, R. (1996). The rise of virtual state. Foreign Affairs, 47(1), 45–46.

Rothstein, B., & Stolle, D. (2008). The state and social capital: An institutional theory of generalized trust. Comparative politics, 40(4), 441–459.

Samara, G., & Arenas, D. (2017). Practicing fairness in the family business workplace. Business Horizons, 60(5), 647–655.

Samara, G., & Paul, K. (2019). Justice versus fairness in the family business workplace: A socioemotional wealth approach. Business Ethics: A European Review, 28(2), 175–184.

Schmidt, E. (2011, May 16). The internet is the path to Britain’s prosperity. The Daily Telegraph.

Smith, D. (2009). Financial bootstrapping and social capital: How technology-based start-ups fund innovation. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 10(2).

Steier, L. (2009). Where do new firms come from? Households, family capital, ethnicity, and the welfare mix. Family Business Review, 22(3), 273–278.

Winborg, J., & Landström, H. (2001). Financial bootstrapping in small businesses: Examining small business managers’ resource acquisition behaviors. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(3), 235–254.

Wu, B. (2015, August 21). A moment that changed me—Gamergate. The Guardian.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Samara, G., Terzian, J. (2021). Challenges and Opportunities for Digital Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries. In: Soltanifar, M., Hughes, M., Göcke, L. (eds) Digital Entrepreneurship. Future of Business and Finance. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53914-6_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53914-6_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-53913-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-53914-6

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)