Abstract

The German administrative system is well known for its time-honoured subsidiarity principle regarding the delivery of social and welfare services, especially at the local level. The public (municipal) sector is only allowed to provide these welfare services if the civil society, welfare organisations and citizens’ initiatives are not able to do it on their own. Against this background, the co-production of public services is deeply rooted in the German administrative culture. However, in more recent times, often prompted by fiscal problems, but also triggered by an increasing demand for more citizen participation, the co-production of services and the involvement of multiple actors have gained increasing importance. Against this backdrop, the chapter outlines these shifts from ‘traditional’ modes of service delivery and decision-making to co-producing features and participatory elements. It also addresses some of the resulting key problems and pitfalls, such as accountability, transparency and legitimacy.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Citizens face ‘their’ public administration in different roles: as more or less passive ‘subjects’ and ‘customers’, as passive ‘financiers’ (taxpayers), as active political ‘principals’ and ‘co-producers’ of public goods. Additionally, in some of their interactions with the public sector, citizens act as individuals, in others as members (or users) of organisations such as associations, citizens’ initiatives and non-profit organisations. On the one hand, the German state tradition has long been described as seeing the state as being superordinate to society and conceiving citizens primarily as subjects (Untertanen) (Dyson 2009). On the other hand, influenced by Catholic social ethics, Germany developed early a strong tradition of ‘subsidiarity’ with voluntary organisations from the ‘third sector’ (Evers and Laville 2004) producing public goods alongside public bodies. These voluntary organisations were united under umbrella organisations, the so-called welfare associations, which also have a strong role in the formulation and implementation of policies. This dense partnership between the voluntary sector and the state has often been labelled ‘neo-corporatism’ (Heinze and Strünck 2000; Zimmer 1999).

The ambiguous relationship between state and society has changed considerably in recent decades—at both the micro level of individual citizens (Bogumil and Holtkamp 2004) and the meso level of third sector organisations (Grohs 2014; Grohs et al. 2017; Zimmer and Evers 2010). Since German reunification, ‘participation’ has gained increased attention from policymakers. First, citizens claimed their roles as active citizens in demanding more participatory rights. With the general increase in levels of educational attainment and value shifts towards post-materialistic orientations, the expectations of citizens to participate in public affairs increased (Evers 2019). After reunification, every German state (Länder) introduced new forms of direct democracy and many local governments experimented with stronger participatory processes, for example in planning decisions and budgeting. Second, established ‘corporatist’ modes of co-production have been challenged by new forms of citizen engagement and private for-profit actors criticising the old ‘oligopolies’ of welfare production. Third, there are functional reasons for actively promoting co-production. Fiscal constraints, especially at the local level, and problems associated with shrinking rural areas in some parts of Germany pose additional challenges for the provision of public services. Finally, new challenges, especially the integration of refugees since 2015, have paved the way for new forms of citizen involvement in public affairs.

The new relationship between state and citizens has been categorised under different, more or less synonymous, labels: ‘participatory administration’, ‘co-production’ and ‘cooperative democracy’. Whereas the latter term is more common in the German debate (Holtkamp et al. 2006), the term ‘co-production’ is used throughout this article, as it is more familiar to an international readership (Bovaird and Loeffler 2012; Brandsen and Pestoff 2006). ‘Co-production’ describes different practices of cooperation between individual or organised citizens and the public sector in developing and implementing public goods. Apart from the classic distinction of state and society, co-production means a productive interpenetration of both spheres, ideally in a symmetric and reciprocal way. Citizens are seen as active producers and not as passive recipients of public goods. Administrative actors do not react on ‘disturbances’ by citizens claiming their rights, but actively develop citizens’ competences and opportunity structures to act for a common cause (Bovaird and Loeffler 2012).

There are several functional and political reasons for the support of the public sector for co-production. First of all, the inclusion of additional knowledge (especially from those directly affected) fosters an effective design and participation in the decision-making processes of policies. Second, the activation of additional resources (especially voluntary work and the provision of rooms or equipment) reduces (public) costs. Third, the involvement of citizens and relevant groups can enhance the acceptance of programmes and increase the compliance of target groups. Fourth, activating citizens to participate can strengthen solidarity and ‘social capital’. Finally, the experience of participation can strengthen (local) democracy and enlarge the pool of candidates for classic representative democracy (Bogumil and Holtkamp 2004; Bovaird and Loeffler 2012). To structure the following assessment on the state of co-production in Germany, I will refer to four aspects of co-production according to Bovaird and Loeffler (2012):

-

co-design: participation in planning and the preparation of decision-making;

-

co-decision: legislation and other forms of binding decision-making;

-

co-implementation: co-production of public value through cooperative implementation; and

-

co-evaluation: assessment of public performance through public consultation and evaluation mechanisms (as this dimension is still underdeveloped in Germany, its own section has been omitted in the following).

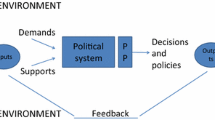

In the following sections, I provide an overview of the major reform developments since the beginning of the 1990s and focus first on participatory reforms on the ‘input side’ of the politico-administrative system, that is the strengthening of co-design (see Sect. 2 below) and co-decision-making (see Sect. 3 below). Second, I survey developments in matters of co-implementation (see Sect. 4 below). Each chapter first sketches out the status quo ante, then addresses major reforms, which is followed by a discussion on the experiences and problems of the new ‘participatory state’. The concluding paragraph resumes the arguments, discusses future challenges of participatory public administration in Germany and identifies potential for transfer (see Sect. 5 below).

2 Co-design: From Expert Knowledge to Citizens’ Expertise?

Surely one of the most common forms of co-production is the participation of citizens in the design and planning of policies in binding or mostly non-binding forms. This form of participation has its roots in formal participation in planning procedures. For example, Section 3 of the German Building Code (Baugesetzbuch) stipulates that the public should be informed early about the aims, purposes, alternatives and impacts of planning procedures, and is given the opportunity to comment and participate in discussions. Similar regulations apply in the context of planning procedures (Planfeststellungsverfahren; Section 73 of the Administrative Procedures Act, VwVfG, see Chap. 8) and within the scope of environmental regulations, for example the Federal Nature Conservation Act (Grohs and Ullrich 2019). In Bavaria, the municipal code (Gemeindeordnung) specifies that a citizens’ assembly to deliberate on all local issues is held (at least) once a year.

In addition to these mandatory forms, voluntary non-formal participation is becoming increasingly important as part of administrative governance (Bogumil and Holtkamp 2004; Kersting 2016; Vetter et al. 2016). In these arrangements, governments and political bodies not only seek support and legitimisation for their decisions but also the specific expertise of citizens in their own affairs. Today, a plethora of non-formal and voluntary forms of participation exists, especially at the local level, but also in other public institutions. They vary especially according to the level of citizens’ involvement and deliberation. At one extreme, certain participatory formats are merely informational and asymmetric in nature (e.g. citizens’ assemblies and other information events that have very little room for questions concerning proposals put forward by public institutions). Examples of more dialogue-oriented instruments include ‘citizen forums’ (e.g. round tables, citizens’ conferences and workshops, etc.), ‘planning cells’ (a randomly selected group of people work together to develop proposals in a limited period of time—and often learn from citizens’ expertise) and mediation procedures to address escalating conflicts.

These participatory events typically focus on a specific issue and are conducted during a fixed and narrowly defined time period. More general and holistic processes are seldom. As an exception, so-called citizens’ budgets have become popular in many local governments (Sintomer et al. 2016). They address the cross-cutting issue of budgeting and develop proposals for the prioritising of budget items in a regular time frame. Examples of other ongoing participation processes include municipal advisory councils dealing with different issues (e.g. environment or health) and boards for specific status groups (e.g. juveniles, immigrants and senior citizens). In these councils, interested members of the public have the opportunity to provide input throughout the decision-making processes of the authorities with a long-term perspective. Some of them are obligatory and anchored in municipal law, others are voluntary.

While citizens’ petitions and referendums, which are discussed in the next section, can produce binding decisions, the voluntary forms of participation are only consultative for political actors and the administration. With their expansion, the politico-administrative system hoped for a stronger input legitimacy, aiming to increase the acceptance of controversial projects. Several problems arise from the expansion of such participatory processes. On the one hand, supplementing representative democracy with elements of dialogue-oriented participatory democracy arouses the grievances of councillors and members of parliaments concerning their future role as elected representatives. On the other hand, the non-binding character of results can lead to frustration among participants if their proposals are not ratified by councils or parliaments. This can subvert the legitimacy of decision-making and damage the (local) political culture. The legitimacy of the results of these processes is especially challenged by an asymmetric mobilisation, that is the selective participation of certain citizen groups. The ‘usual suspects’ in all kinds of voluntary participatory formats can be divided into two groups: in one group the well-off, well-educated citizens with enough spare time (i.e. mostly elderly academics) and those directly affected by the disputed measures (i.e. the famous NIMBYs) in the other. Whereas the first group tends to reproduce social inequalities (middle-class bias), the latter dilutes the common good with private concerns. In complex matters, citizens are often overwhelmed by the problems at stake (which can be solved by administrative actors having a competent moderator).

Some instruments (e.g. planning cells) try to avoid a misrepresentation by selecting a more or less representative sample of citizens. Nevertheless, these approaches remain isolated and are comparatively expensive. Especially at the local level, administrations are meanwhile experimenting with digital solutions (e-participation, citizen panels, online fora, etc.) and new forms of participation (‘gamification’; Masser and Mory 2018) to attract broader groups of citizens and to foster the participation of younger people. Even if these procedures are controversial in terms of representative democratic theory, they can improve the quality and acceptance of decisions and introduce elements of deliberation into decision-making processes, insofar as they are supported by democratic majorities. At the same time, participation binds administrative resources and, in some cases, extensive participation can impede decision-making considerably. Therefore, increased participation is not a panacea for modern democracy and the pros and cons should be weighed up in each case.

3 Co-decision-making: From Representative Democracy to a New ‘Power-triangle’?

Since the 1990s, the rights of citizens to participate in binding decisions at the local and state level have been strengthened. These reforms, primarily directed towards the municipal level (Bogumil and Holtkamp 2004; Vetter et al. 2016), were based on the introduction of elements of direct democracy through the introduction of citizens’ petitions and referendums, and the direct election of mayors and heads of counties. With the exception of Baden-Württemberg and Bavaria, where both features have a long tradition, both elements were introduced by all states between 1990 and 1997 at both the state and the local level. Nevertheless, state regulation for petitions and referendums differs considerably regarding the range of topics allowed and the requirements in terms of quorums (Mehr Demokratie 2018). The federal level still denies direct democratic elements (with the exception of a revision of state territory boundaries according to Article 29 of the Basic law).

A referendum can be initiated by citizens (citizens’ referendum: Bürgerbegehren) and by the parliament or the local council (council’s referendum: Ratsreferendum) (see Chap. 6). For a referendum initiated by citizens on factual issues to succeed, citizens have to overcome several hurdles. First, a defined number of valid signatures are necessary. This threshold varies from state to state and depends on the size of the municipality (the larger the municipality, the lower the quorum) and varies between 2% to 3% in Hamburg and 10% in Brandenburg. Saarland, one of the smaller municipalities, requires 15% of citizens to sign (Bürgerbegehrensbericht 2018: 11). Second, if a sufficient number of valid signatures are obtained, the council must then decide on the applicability of the referendum. The most important question here is whether the issue of the initiative falls within the legally defined range. Usually, issues with direct relevance to the budget are excluded. Some states like Bavaria, Berlin and Hamburg allow referendums on a wide range of issues, while others are quite restrictive (e.g. Brandenburg, Saarland and Rhineland-Palatinate) (for details see Bürgerbegehrensbericht 2018: 11). Finally, to be accepted, a referendum must reach a certain quorum of votes to be successful. Again, the quorum depends on the size of the municipalities and the height of this hurdle differs from state to state. The lowest hurdles can be found in Bavaria and Berlin (between 10 and 15%) and Hamburg (where no quorum exists at all). The highest quorums can be found, for example, in Brandenburg, Saxony and the Saarland between 25 and 30%.

This regulatory divergence is one reason for the varying use of these instruments between the states as well as between local governments. Generally speaking, the lower the thresholds, the more often referendums take place. Of the 7503 referendums held since 1956, over one-third (2910) took place in Bavaria. Looking at the shorter period from 2013 to 2017, the picture remains the same: Bavaria held the largest number of referendums per inhabitant, followed by the states of Baden-Württemberg and North Rhine-Westphalia. The lowest numbers can be found in Saarland and in the East German states (Bürgerbegehrensbericht 2018: 19). The issues have mostly concerned public facilities, traffic projects and other public building projects.

As in the case of dialogue-oriented instruments, the new entitlements of citizens to have a say have been critically evaluated by proponents of representative democracy as a weakening of the representative elements, especially of local democracy. In the case of citizens’ petitions and decisions, parliaments and city councils in particular lose their representative monopoly directly (through opposing citizens’ petitions) or indirectly (through the mere threat of such a procedure, often a strategy of opposition parties). However, there are few empirical indications that this instrument is used so frequently that these fears are firmly based. In this respect, the indirect effects are more important for the decision-making processes. Referendums have also been criticised for their simplistic approach to social problems, reducing complex issues to dichotomous questions that ask for a Yes/No. In addition, referendums often show a negative bias as they mostly try to hinder projects (typically large-scale infrastructure projects) or defend existing arrangements (typically to prevent closures of public facilities such as schools, swimming baths, theatres, etc.). Positive approaches and the proposal of realistic alternatives remain in a minority of issues.

4 Co-implementation: From Corporatism to Activation and Civic Pluralism?

In this section, I first discuss co-implementation regarding civic activism for public purposes (see Sect. 4.1 below) and then turn to the transformation of welfare production by civic associations (see Sect. 4.2 below).

4.1 Activating Citizens: The Promotion of Voluntary Activism

A major effort to promote participatory approaches to co-production was triggered in 1998 by the first red-green coalition at the federal level with its emphasis on the ‘activating state’ (Blanke and Schridde 2001). A parliamentary committee of enquiry (Enquête-Kommission) on civic engagement developed a broad agenda on activating citizens for the common good. For example, the number of local volunteer agencies (Freiwilligenagenturen), where opportunities for volunteering are conveyed to citizens, spreads. This movement could rely on a strong latent potential for civic co-production, which is monitored on a regular basis by the survey on volunteering, commissioned by the federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth (BMFSFJ 2017). About 45% of the German population interviewed claim to volunteer in one or another area, most of them in sports, education, cultural affairs and social purposes (BMFSFJ 2017).Footnote 1 This has increased over the past few decades and varies between regions and social groups. A larger proportion of citizens are engaged in volunteering in the west of Germany than in the east (BMFSFJ 2017: 22) and in rural areas, engagement is more widespread than in urban areas (BMFSFJ 2017: 25). Those who volunteer are usually better educated and better off (BMFSFJ 2017: 16). Besides the increase in numbers, the character of voluntary engagement has also changed over the past few decades. People spend less time on voluntary activities and younger people especially tend to engage more selectively and in less formal ways than before. They are more reluctant to take leadership roles in associations and other organisations (BMFSFJ 2017: 28). There seems to be a further potential for volunteering as a considerable number of people not already involved in volunteering express themselves willing to volunteer in the future (BMFSFJ 2017: 28). Some administrations, especially local governments, try to mobilise this latent potential for volunteering with local agencies for volunteering and other low threshold kinds of volunteering opportunities.

A large part of these voluntary activities is organised by associations and other organisations. About 70% of the German population are members of at least one association, but are not always committed in an active way (e.g. the largest ‘association’—the German automobile club (ADAC)—is merely a service provider, not an arena for voluntary engagement). Among these organisations, sports clubs, educational and cultural associations organise the largest part. These occupations might seem to be merely ‘private’ activities, nevertheless the associations play a significant role in organising public goods and forming social solidarity and social capital (Zimmer and Evers 2010). Therefore, such associations are supported financially and in terms of free access to public facilities, for example, sports facilities or rooms in schools and other public buildings by local governments. Some local governments, driven by fiscal pressures, have gone even further and transferred the operation of public facilities (e.g. youth clubs, swimming baths and other sports facilities) to associations (e.g. swimming clubs) on condition that the association looks after the facilities and guarantees access to the wider public (Bogumil and Holtkamp 2004). This development can be dangerous if citizens feel they are being exploited for buffering budget cuts by public institutions. Participation and co-production are scarce resources. Over-use and perceived inefficacy are among the perils of all efforts to strengthen the role of citizens. If people have the impression that they are purely serving as legitimisers of ex-ante decisions, or that the value of their participation is being largely ignored, this is as dangerous as when volunteers feel they are being taken advantage of doing the same tasks previously performed by paid professionals.

These traditional arrangements for volunteering by associations and other organisations (e.g. voluntary fire brigades) are being challenged by an increasing orientation towards private engagement and more mobile biographical patterns. Younger adults especially tend to engage in new, more flexible forms and are not being reached by traditional associations. As modern biographies include a greater proportion of job-related geographical mobility, associations are becoming more unstable and experiencing difficulty in finding people who are willing to show enduring commitment, for example to serve in management and leadership positions in the associations. In terms of public administration, such unstable patterns on the part of associations come with the problems of maintaining reliability and continuity, necessary preconditions for the transfer of ambitious tasks.

4.2 An End of Corporatism? Pluralising Welfare Arrangements

Building on a strong tradition of local social care by church parishes, since the end of the nineteenth century a mixed system of welfare provision has developed where church parishes and local charities run hospitals, homes for handicapped people or orphans’ homes. In the early twentieth century, accompanied by the expansion of the German welfare state, this arrangement expanded to include other areas such as social care, youth welfare and a dense network of counselling institutions. In the 1920s, this scheme became regulated by law, when the ‘principle of subsidiarity’ was anchored in social law, claiming that the public (municipal) sector is only permitted to provide these welfare services if civil society, welfare organisations and citizens’ initiatives are not able to do it on their own (Grohs 2014; Heinze and Strünck 2000). From this time onwards, the duality of public responsibility (Gewährleistungsverantwortung, see also Chap. 17) and organised civic provision has become increasingly institutionalised. A corporatist mode of governance has emerged at the local level with a division of labour developing between local governments and non-profit organisations unified in the so-called Wohlfahrtsverbände (welfare associations).Footnote 2 As a consequence, the third sector as a whole is the largest employer in Germany today. Among its organisations, the welfare associations and its member organisations represent the bulk of professional occupations. In the past, these organisations were able to channel the voluntary commitment of individual citizens and at the same time develop professional structures with employed staff to guarantee stability.

At the governance level, these non-profit organisations had privileged access to both welfare provision and political decision-making bodies, for example through functional representation in local committees, such as youth welfare committees (Jugendhilfeausschüsse). Services were subsidised by local governments and social insurances according to the principle of cost coverage, and the cost-bearing units generally refrained from introducing standardised measures of quality control. These arrangements were stabilised by close ties between welfare associations and local politics—often along party lines—as well as between the associations and welfare administrations. Far from being mere substitutes for state activity, welfare associations combined a role of advocacy with the mobilisation of their memberships and volunteers. In addition to the functional relief of public bodies, one of the main motivations behind these arrangements was the incorporation of the specific (and diverse) value orientations of the associations and the additional resources provided by their memberships. This has often led to a ‘co-evolution’ of public and private bodies, but the organisations retained their distinct identities and were also able to adapt to changing economic environments (Heinze and Strünck 2000).

These established arrangements came under pressure in the 1990s. The reasons were first of all the fiscal pressures, but also the obvious governance deficits and lack of accountability measures of the organisations (Seibel 1996) as well as demands for more ‘pluralism’ or ‘market’. Actors from the left and the liberal side of the political spectrum unanimously criticised the corporatist oligopoly of the welfare associations and its members. From the left, the heirs of the alternative movements and self-help activists claimed their share of public financial support; from the liberal side, for-profit providers advocated for equal treatment as the welfare associations (Evers 2005). One political response to these pressures has been the implementation of managerial reform measures and the introduction of quasi-market principles, which were often subsumed under the headings of ‘managerialism’ or ‘marketisation’. These reform measures followed the international paradigm of New Public Management (Pollitt and Bouckaert 2011) and were adapted to the German discussion on the New Steering Model (Kuhlmann et al. 2008, see also Chap. 22). These strategies were not primarily targeted at the reduction of services, but rather at the more efficient and effective allocation of resources. In this context, the activation of competition had an important role, with private for-profit actors sometimes acting as competitors to the established system. The establishment of competition between providers went hand in hand with the replacement of the traditional principle of cost coverage by fixed prices as well as the abolishment of the privileges of charities. The abandonment of the old corporatist model of welfare production was incorporated into all the relevant welfare acts (Grohs 2014).

The discussions on quality and impact measurement in the field of social services have been extensive, but the comprehensive implementation of established and acknowledged standards is still a long way off. In some areas, such as care for the elderly, a series of control measures to increase transparency in the sector (quality records, care grades) have been introduced in recent years. The degree of change differs between the subfields, as can be seen if we compare services in elderly care with youth welfare. Whereas in the care sector new actors have gained considerable market shares, in the field of youth welfare established arrangements have continued (Grohs et al. 2017, see Table 18.1).

After almost thirty years of quasi-market reforms in the German welfare system, no clear-cut conclusions regarding their consequences for the character of the organisational field, its governance mechanisms or its constituent organisations can be drawn. Despite tendencies towards privatisation and marketisation in the care sector, the so-called freigemeinnützigen (non-profit) organisations continue to provide the majority of social services. The growing market orientation clashes with the welfare associations’ traditional roles as advocates and promoters of voluntary action.

Summing up, we can identify two competing rationales regarding the co-implementation of services in Germany. On the one hand, the traditional modes of organising voluntary work in the traditional welfare organisations are being challenged (primarily by quasi-market mechanisms) and new forms of voluntary work are being promoted on the other. One recent development is the support of so-called social entrepreneurship, which will bring more innovation through ‘entrepreneurial action’. A concept promising innovative approaches, ‘social entrepreneurship’ seeks to develop new forms for civic engagement, which acknowledge changes in participatory behaviour and communication technology (Grohs et al. 2017). The focus on single entrepreneurial organisations may, however, distract from a far more urgent issue: how to bring about more cooperation and networking to address complex problems. Civic and public organisations working in parallel need to find new ways to cooperate. This may avoid potential losses of momentum and consolidate resources with the aim of expanding the local social infrastructure. The role of public administration in the participative state is still pivotal as participation has to be managed and coordinated more than ever.

5 Lessons Learned: Rediscovering the Citizen: About Mute Euphoria, Some Frictions and Old Patterns of Participatory Administration

Recent decades have seen a rediscovery of the citizen as a partner (and resource) of public administration—on the input side as well as on the implementation side of public policies. These developments have been driven by the changing demands of citizens, fiscal constraints and the declining effectiveness of public administration to tackle ‘wicked’ problems. The term ‘co-production’ has gained momentum as a promise for a new balance between the public sector and civil society actors. This agenda is attractive for political actors as it combines a reduced public responsibility with a potential increase in legitimacy.

Nevertheless, findings from this survey on different aspects of participatory administration in Germany reveal some friction. On the input side of co-design and co-decision-making, research shows several hitches and asymmetries which have the ability of subverting the potential for increased legitimacy and effectiveness. The perceived loss of relevance of representative democracy is an important issue and one that is voiced by most members of parliaments and local councils. This is reflected in the unwillingness of politicians to contest the role of professionals and place more trust in citizens. In addition, the question of whether citizens are willing to participate more intensively is far from clear. Many referendums fail to reach the necessary quorum and many deliberative events fail to attract participants from a broader spectrum of socio-cultural backgrounds. The hope for smoother implementation by early participation is often diluted by the experience of participation processes in large-scale planning, where planning periods are substantially prolonged (see Chap. 11) without increasing the acceptance of planning results.

On the implementation side, a major concern about co-production is that it tends to dilute public accountability, blurring the boundaries between the public, private and third sectors. The problem increases with the sheer numbers of actors involved. In the ‘old’ world of welfare corporatism, the associations could claim a hybrid mix of professionalism, value orientation and embeddedness in societal networks. Today, secularisation and individualisation have reduced the willingness of people to volunteer in welfare associations. Additionally, the quasi-market reforms of the 1990s have transformed the organisations themselves. The separation between the spheres of service provision and normative and social integration is wider. This signifies that simple delegation chains hardly contribute to the determination of policy results. The resulting tasks of quality assurance and effectiveness, the consolidation of participation in reliable partnerships and the intervention in cases of defection and failure by civic partners remain core competencies of public administration.

In this context, German public administration needs to assume new roles of facilitator and coordinator, but sometimes also as ‘realist brakeman’. As a result, the public sector has to face new challenges, such as qualifying volunteers to deal with demanding tasks (e.g. accompanying refugees, tutoring and quality assurance). Activating people with social backgrounds typically considered unsuitable for social participation is another challenging step towards more legitimate co-production.

But there are also many opportunities. Digital transformation (see Chap. 19) can cause patterns in civic participation and co-production to change. With open government and freedom of information acts, the information base of citizens has become broader. Digital participation formats can result in lower social thresholds and allow for more attractive formats (Masser and Mory 2018) as well as help organise voluntary engagements (e.g. Uber for Volunteering). On the other hand, digital offers come with the risk of low commitment and new inequalities. At a time when traditional forms of co-production in infrastructure maintenance (Kehrwoche) and public security (voluntary fire brigades) are struggling to motivate citizens to contribute, it is hard to imagine that digital solutions alone can step in and help.

The German experience shows that participatory reforms and co-production have to be handled with care and need to be adaptive to local circumstances and time frames. A sensible use of civic resources has the potential to increase legitimacy and improve results. However, a naïve reliance on civil society can also dilute responsibilities and increase social inequalities. Some of the defining characteristics of the German context, such as the prominence of welfare associations, are difficult to transfer to other contexts. Other findings, for example the measures adopted to soften social selectivity in participation processes aimed at mobilising citizens for voluntary work, or the importance of institutional barriers for referendums, may be easier for interested observers to adopt.

Notes

- 1.

All data presented in this paragraph stem from the Fourth German Survey of Volunteering, a publicly financed survey based on about 28,600 telephone interviews; for methodological details, see BMFSFJ (2017: 11–13).

- 2.

These welfare associations are the catholic Caritas, the protestant Diakonisches Werk, the Jewish Zentralwohlfahrtsstelle der Juden in Deutschland, the social-democratic Arbeiterwohlfahrt, the German Red Cross and the secular Paritätische Wohlfahrtsverband. They are organised federally, resembling the basic architecture of the German federal state. Together, their subsidiary organisations and institutions represent one of the largest employers in Germany with a total of almost two million employees and more than 100,000 establishments in the fields of social services and education (BAGFW 2018).

References

Blanke, B., & Schridde, H. (2001). Bürgerengagement und aktivierender Staat. In R. G. Heinze & T. Olk (Eds.), Bürgerengagement in Deutschland (pp. 93–140). Wiesbaden: VS.

Bogumil, J., & Holtkamp, L. (2004). The Citizens’ Community under Pressure to Consolidate? German Journal of Urban Studies, 44(1), 103–126.

Bovaird, T., & Loeffler, E. (2012). From Engagement to Co-production: The Contribution of Users and Communities to Outcomes and Public Value. VOLUNTAS, 23, 1119–1138.

Brandsen, T., & Pestoff, V. (2006). Co-production, the Third Sector and the Delivery of Public Services. Public Management Review, 8, 493–501.

Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft der Freien Wohlfahrtspflege (BAGFW) (2018). Gesamtstatistik. Berlin: BAGFW.

Dyson, K. H. F. (2009). The State Tradition in Western Europe. Colchester: ECPR Press.

Evers, A. (2005). Mixed Welfare Systems and Hybrid Organizations: Changes in the Governance and Provision of Social Services. International Journal of Public Administration, 28, 737–748.

Evers, A. (2019). Diversity and Coherence: Historical Layers of Current Civic Engagement in Germany. VOLUNTAS, 30, 41–53.

Evers, A., & Laville, J.-L. (Eds.). (2004). The Third Sector in Europe. Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth. (2017). Volunteering in Germany. Key Findings of the Fourth German Survey on Volunteering. Berlin: BMFSFJ.

Grohs, S. (2014). Hybrid Organizations in Social Service Delivery in Quasimarkets: The Case of Germany. American Behavioral Scientist, 58, 1425–1445.

Grohs, S., Schneiders, K., & Heinze, R. G. (2017). Outsiders and Intrapreneurs: The Institutional Embeddedness of Social Entrepreneurship in Germany. VOLUNTAS, 28, 2569–2591.

Grohs, S., & Ullrich, N. (2019). A Guide to Environmental Administration in Germany. Dessau: Umweltbundesamt.

Heinze, R. G., & Strünck, C. (2000). Social Service Delivery by Private and Voluntary Organisations in Germany. In H. Wollmann & E. Schröter (Eds.), Comparing public Sector Reform in Britain and Germany (pp. 284–303). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Holtkamp, L., Bogumil, J., & Kißler, L. (2006). Kooperative Demokratie: Das demokratische Potenzial von Bürgerengagement. Frankfurt am Main: Campus.

Kersting, N. (2016). Participatory Turn?: Comparing Citizens’ and Politicians’ Perspectives on Online and Offline Local Political Participation. Lex localis, 14, 251–236.

Kuhlmann, S., Bogumil, J., & Grohs, S. (2008). Evaluating Administrative Modernization in German Local Governments: Success or Failure of the ‘New Steering Model’? Public Administration Review, 68, 851–863.

Masser, K., & Mory, L. (2018). The Gamification of Citizens’ Participation in Policymaking. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mehr Demokratie e.V. (2018). Bürgerbegehrensbericht 2018. Berlin: Mehr Demokratie e.V.

Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2011). Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis; New Public Management, Governance, and the Neo-Weberian State (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Seibel, W. (1996). Successful Failure: An Alternative View on Organizational Coping. American Behavioral Scientist, 39, 1011–1024.

Sintomer, Y., Röcke, A., & Herzberg, C. (2016). Participatory Budgeting in Europe: Democracy and Public Governance. Florence: Taylor and Francis.

Vetter, A., Klimovský, D., Denters, B., & Kersting, N. (2016). Giving Citizens More Say in Local Government. In S. Kuhlmann & G. Bouckaert (Eds.), Local Public Sector Reforms in Times of Crisis (pp. 273–286). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Zimmer, A. (1999). Corporatism Revisited. Voluntas, 10, 37–49.

Zimmer, A., & Evers, A. (2010). Third Sector Organizations Facing Turbulent Environments: Sports, Culture and Social Services in Five European Countries. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Grohs, S. (2021). Participatory Administration and Co-production. In: Kuhlmann, S., Proeller, I., Schimanke, D., Ziekow, J. (eds) Public Administration in Germany. Governance and Public Management. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53697-8_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53697-8_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-53696-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-53697-8

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)