Abstract

Crowdsourcing has become one of the main resources for working on so-called microtasks that require human intelligence to solve tasks that computers cannot yet solve and to connect to external knowledge and expertise. Instead of using external crowds, several organizations have increasingly been using their employees as a crowd, with the aim of exploiting employee’s potentials, mobilizing unused technical and personal experience and including personal skills for innovation or product enhancement. However, understanding the dynamics of this new way of digital co-working from the technical point of view plays a vital role in the success of internal crowdsourcing, and, to our knowledge, no study has yet empirically investigated the relationship between the technical features and participation in internal crowdsourcing. Therefore, this chapter aims to provide a guideline for organizations and employers from the perspective of the technical design of internal crowdsourcing, specifically regarding issues of data protection privacy and security concerns as well as task type, design, duration and participation time based on the empirical findings of an internal crowdsourcing platform.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Thanks to the widespread use of the Internet, a fast and relatively inexpensive resource, so-called microtask crowdsourcing, has emerged, meaning that the cost and time barriers of qualitative and quantitative laboratory studies, controlled experiments, challenges in innovation and product enhancement can be easier overcome (Kittur et al. 2011; Gadiraju 2018). Microtask crowdsourcing has been primarily used for simple, independent tasks such as image labelling or digitizing print documents (Kittur et al. 2011). One of the well-known examples of crowdsourcing is Wikipedia, where crowdsourcing is used to gather knowledge from people from all over the world. They bring together a collection of images, links and topics, tag the content, sort it into categories and link and recommend content to each other. Inspired by the results of microtask crowdsourcing, some researchers have begun to investigate crowdsourcing for complex and expert tasks such as writing, translating, product design or product innovation (Kittur et al. 2013; Valentine et al. 2017; Zuchowski et al. 2016). Progressive digitization and the global networking associated with it are also leading to a change in the professional world, meaning that the use of crowdsourcing in enterprises has increased substantially as a direct result of widespread use of Internet applications and digitalization.

This new form of digital agile work, both in terms of collaboration and the knowledge transfer processes, has aroused the interest of many enterprises where the same pattern of online working is used internally. In that way, crowdsourcing has evolved and created a new form which is referred to as ‘internal crowdsourcing’. It involves outsourcing certain work steps and tasks from the daily tasks, production or innovation processes or any kind of topic that might be interesting for employees, via company-owned online platforms or intermediaries to a predefined group of company employees (Zuchowski et al. 2016; Erickson et al. 2012; Vel et al. 2018). In this case, value-added activities are not outsourced to an indefinite mass of people, the so-called external crowd, but to a closed group of people such as employees or other stakeholders (Leimeister et al. 2015).

This also has far-reaching consequences for companies and the way they use the Internet for their diverse work processes. This new way of digitalization and work organization is increasingly becoming an alternative to the traditional way of working in organizations, especially in the innovation and participation domain (Benbya and Leidner 2016; Benbya and Leidner 2018; Malhotra et al. 2017). Apart from collecting information on any topic, organizations can apply internal crowdsourcing for complex tasks such as idea creation, product evaluation or innovation generation, which are mostly quite complex and require special knowledge and skills. This new concept is implemented in practice at numerous large companies. For example, the American consumer goods producer Procter & Gamble, the pharmaceutical company Bayer HealthCare and the toy manufacturer LEGO use the crowdsourcing strategy to achieve higher-quality, cheaper and faster innovation processes (Zuchowski et al. 2016).

The idea that the innovation or idea creation processes are opened to all the employees (not just the employees of strategy or innovation department) is interesting for many companies because this type of crowdsourcing uses the principle of the ‘wisdom of the crowd’. This is the phenomena whereby a heterogeneous group of individually decisive people can produce qualitatively better solutions than certain experts under certain conditions (Lüttgens et al. 2014). In that way, organizations can benefit from the internal knowledge and personal experience of all employees and involve them in the innovation process without any additional costs. For example, Dieter Zetsche—the Chairman of the Board of Management of Daimler AG—recently announced that 20% of the employees will be transformed into an internal crowd to operationalize a series of innovation tasks (Daimler 2017). However, designing and building such a large internal crowd involves a significant organizational transformation process that needs to be managed (Malhotra and Majchrzak 2014). Allianz UK has shown how tedious this change can be when they launched an internal crowdsourcing platform for innovation development (Benbya and Leidner 2016; Benbya and Leidner 2018). More than 8 years have passed from commissioning to the efficient use of the platform.

Since internal crowdsourcing is not yet a standardized procedure, the internal crowdsourcing task design, the foundation of the employee’s motivation to participate, the measures of quality and success for internal crowdsourcing as well as ground rules for protecting employee rights and privacy should be established for an ethical and successful operationalization of internal crowdsourcing (Zuchowski et al. 2016). Chapters ‘Introduction to “Internal Crowdsourcing: Theoretical Foundations and Practical Applications”’ and ‘Systematization Approach for the Development and Description of an Internal Crowdsourcing System’ provide the theoretical background for internal crowdsourcing; however, to our knowledge, no study has yet empirically investigated the effects of crowdsourcing campaign topics, the estimated timeframes involved, the time and day for employee participation in the campaign or the question types to be used in the campaign concerning the participation of employees in the internal crowdsourcing. As such, the empirical results of internal crowdsourcing should be further investigated to find out what kind of relationship exists between the technical characteristics of an internal crowdsourcing platform and employee participation.

This chapter aims to provide some initial insights about how to shape and communicate the rules regarding data protection, privacy and security concerns of employees as well as the guidelines for technical implementation of such a platform and its daily operation. Its anticipated contribution towards the practical implementation is the establishment of ground rules for fair internal crowdsourcing to lower the barriers to employee participation. The following section of the chapter explains the review and synthesis of the external and internal crowdsourcing in the literature. The subsequent section then presents the basic function of an internal crowdsourcing platform based on an empirical example of it. The penultimate section highlights the research methods and internal crowdsourcing tasks that have been conducted using an internal crowdsourcing platform and provides an empirical analysis of these. In the last section, the discussion and conclusion of the empirical results are presented.

2 Theoretical Background

The term ‘crowdsourcing’ was first used by the American journalist Jeff Howe (2006) in an article entitled ‘The Rise of Crowdsourcing’, which was published in the technology magazine Wired (Howe 2006). It is a neologism from the words ‘crowd’ and ‘outsourcing’, and Howe describes it as follows:

The technological advances in everything from product design software to digital video cameras are breaking down the cost barriers that once separated amateurs from professionals. Hobbyists, part-times, and dabblers suddenly have a market for their efforts, as smart companies in industries as disparate as pharmaceutical and television discover ways to tap the latent talent of the crowd. The labor isn’t always free, but it costs a lot less than paying traditional employees. It’s not outsourcing; it’s Crowdsourcing. (Howe 2006)

So, crowdsourcing is a form of participatory online activity involving an individual, an institution, a charity or a company—an undefined group of individuals—through a flexible open call to perform a task voluntarily or in return for some monetary benefit (Geiger et al. 2012).

Brabham takes the results of Howe and focuses on the crowdsourcing from the company’s perspective saying that:

A company posts a problem online, a large number of individual solutions to the problem, the winning ideas are some form of a bounty, and the company mass products the idea for its own gain. (Brabahan 2008)

It becomes clear that Brabahan (2008) considers the crowdsourcing process particularly as a problem-solving method, thus emphasizing the crowd’s swarm intelligence. However, the authors Lopez, Vukovic and Laredo limit the crowdsourcing principle only to the company’s own perspective and see crowdsourcing as an Internet-based production model that enables distributed and Web-based human collaboration (Lopez et al. 2010).

Taking the above definitions into account, three main components of crowdsourcing can be identified: (1) requester or initiator (crowdsourcer), (2) crowd or Internet users (crowdworker) and (3) Internet-based crowdsourcing platform. This is distinguished from outsourcing in that it has a mediator (Internet-based crowdsourcing platform) which enables the communication between an unknown group of people, crowdworkers and the requester (Leimeister et al. 2015). In the case of outsourcing, the requester knows exactly who the task executer is and instructs him/her by giving a certain task in return for monetary payment. In contrast to outsourcing, in external crowdsourcing, the crowdsourcers outsource certain tasks to an Internet-based platform for processing. The undefined mass of people or the so-called crowdworkers take over the processing of outsourced tasks voluntarily or in return for a monetary benefit (Leimeister and Zogaj 2013; Hirth et al. 2012). The entire process, as well as the interaction between crowdsourcers and crowdworkers, takes place on Internet-based crowdsourcing platforms (Blohm et al. 2014; Hoßfeld et al. 2012). It follows that if the crowdworkers are a defined group of people such as employees, stakeholders or members of an organization, then we talk about ‘internal crowdsourcing’ (Leimeister and Zogaj 2013).

In the light of the above definitions, crowdsourcing is defined as a mechanism of task sharing, especially the outsourcing of tasks or orders by crowdsourcers to a wide crowd (crowdworkers) via an open call to solve a particular problem as quickly and effectively as possible. Following that, we separate crowdsourcing based on the crowdworkers into two categories: external and internal crowdsourcing. External crowdsourcing, as explained in chapter ‘Introduction to “Internal Crowdsourcing: Theoretical Foundations and Practical Applications”’, deals with an undefined open, heterogonous and usually unskilled crowd. However, the crowd in internal crowdsourcing describes a closed group of people with certain skills, usually the employees of the company, defined by the requester (Benbya and Leidner 2018).

2.1 Internal Crowdsourcing

In recent years, the still relatively new strategy of crowdsourcing has become increasingly interesting for companies in various industries as a way to redesign and speed up innovation processes and to benefit from the unused internal knowledge of the employee in an organization (Howe 2006, 2009; Hammon and Hippner 2012; Blohm et al. 2014; Simula and Ahola 2014). This type of crowdsourcing is referred to as ‘internal crowdsourcing’ (IC), which is defined according to Zuchowski et al. (2016) as follows:

Internal crowdsourcing is (a) IT-enabled (b) group activity based on (c) open call for participation (d) in an enterprise.

By definition, certain work steps and tasks of a production or innovation process are outsourced using internal crowdsourcing via company-owned online platforms or intermediaries to a predefined group of employees who participate voluntarily in the completion of these crowd tasks online (Leimeister and Zogaj 2013). These are then used to produce innovative, marketable products and services, thus contributing towards increasing the company’s efficiency and profit.

Internal crowdsourcing is still a poorly researched practical phenomenon. Although corporate crowdsourcing is a lucrative process from a corporate perspective, there is an imbalance between the burden and the benefits of crowd activity from the employee’s point of view. For this reason, an incentive system should be developed so that employees can motivate themselves or see benefits in the process as a whole. To ensure that crowdsourcing for employees does not lead to an extra workload, the labour law framework for internal crowdsourcing should also be defined. Also, there are no standards or standardized procedures for task design, task decomposition, task typology, technical requirements for an internal crowdsourcing platform and measurement of the quality of results in internal crowdsourcing. For this purpose, methods that can be used to measure the quality of a creative process are also to be explored. Finally, an ideal process flow (workflow) is needed, which takes into account all aspects of internal crowdsourcing and in an optimal order with associated roles and resources.

2.2 Employee Motivation

In the case of internal crowdsourcing, the incentive system is more diversified, as employees are generally financially secure due to their employment in the company. Fundamentally, there are intrinsic and extrinsic motivations to contribute to the crowdsourcing task from the employee perspective. Intrinsic motivations are when carrying out an action is rewarding for the employee himself, for example, because it brings satisfaction, while extrinsic motivation comes from the expectation of a reward from the outside world as a consequence of an action (Meffert et al. 2018).

One of the intrinsic motivations for employees is their enjoyment of the activity, for example, having fun while testing an internal software, contributing to the ideation of a new product or being intrigued by the competitive nature of crowdsourcing projects (Leimeister and Zogaj 2013). The prospect of helping to shape products in line with their own wishes and ideas and to influence their development can also be crucial from the employee’s perspective (Sixt 2014). This motivation is particularly evident in crowdsolving and crowdcreation, where the motivation here is not in the material reward but in the positive feeling that arises from being involved in the task. Another intrinsic motivation is social exchange within the crowd where the desire to exchange and interact with like-minded people serves as an incentive (Leimeister and Zogaj 2013). Brabham (2013) also mentions the following as essential motivations for participating in crowdsourcing initiatives: ‘to network with other creative professionals’ and ‘to socialize and make friends’. Another intrinsic motivation for participating in internal crowdsourcing is the opportunity to learn within the crowdsourcing engagement and thus enhance personal skills, competencies and experiences through the exercise of relevant tasks so that creative skills can be improved by tackling complex tasks and gaining experience.

Extrinsic motivation comes from the outer world, and the desire for appreciation by other people can also serve as an essential extrinsic motivation in internal crowdsourcing (Leimeister and Zogaj 2013). To feel appreciated by the outside world, e.g. managers and colleagues, crowdsourcing contributions should be visible to other participants, like in competitions where the winner is chosen by the community itself. Participants hoping for recognition from the crowd (their colleges) and company (their employers) are usually motivated to generate high-quality contributions to gain prestige in the company (Franke and Klausberger 2010). Another extrinsic motive is the desire for self-expression or self-marketing. In addition to showing their own contributions to other members of the crowd, self-marketing through crowdsourcing may also improve an employee’s own career opportunities by opening up the possibility that the employer becomes aware of an employee’s high-quality contributions (Leimeister and Zogaj 2013). Monetary rewards can be mentioned as a last extrinsic motive. These can be in the form of monetary compensation, benefits in kind, discounts or certain premiums (Franke and Klausberger 2010).

2.3 Labour Law Framework

As this new way of working sets in motion a fundamental shift in work organization and in the division of labour, minimum standards for fair work in the crowd and fair digital work environment should be defined. To avoid additional workload, the crowd concepts should be designed in a way that takes into account labour policy /legal requirements such as works constitution law, occupational health and safety, trade association regulations, collective bargaining agreements and data protection regulations. Therefore, it is recommended that an official company agreement that regulates all these aspects be drawn up. One of the latest group-wide company agreements for internal crowdsourcing in Germany, ‘Lebende Konzernbetriebsvereinbarung als soziale Innovation’ (the living group works council agreement as social innovation), establishes the rules for a fair crowdsourcing environment for employees (Otte and Schröter 2018). According to Otte and Schröter (2018), the following rules can be applied to any internal crowdsourcing environment:

-

The participation of employees in the internal crowdsourcing is voluntary, and employees are not affected by participation or non-participation.

-

The participation of employees in the internal crowdsourcing takes place during working hours. The time working on the platform is working time.

-

Accessibility to internal crowdsourcing is provided at work via mobile phones or laptops and guaranteed by the company in employees’ home offices as well. There will be no additional IT accesses or IT jobs provided. Employees without IT access can place IC initiatives directly through the crowd manager.

-

The participation of employees in group-public or employer-public points or ranking systems is always voluntarily. Participants have the right to use their real name or a pseudonym.

-

The company is committed to handling data security and data protection in a highly sensitive manner that goes beyond the regulations of the national data protection law. Any and all platform data will be made available for use only in an aggregated and anonymized form to the corporate bodies as well as department heads and supervisors and, upon request, to the research community. A person-related breakdown of data does not take place. The aim is to strengthen employees’ right to determine themselves what happens to their information and to reinforce their confidence in the company and its careful corporate culture.

-

In order to protect employees’ privacy, there will be no online tracking or controlling of employee performance or behaviour.

-

Innovation ideas by employees that are brought into an internal crowdsourcing platform are legally transferred to the company. The idea providers are entitled to appropriate remuneration.

2.4 Tasks in Internal Crowdsourcing

Tasks in internal crowdsourcing are usually like crowdsolving and crowdcreation as described in chapter ‘Systematization Approach for the Development and Description of an Internal Crowdsourcing System’. In larger and more segmented enterprises, it is difficult to match people to the right problem. However, with the help of internal crowdsourcing, the unutilized or unnoticed knowledge of employees can be used by the company internally to generate faster innovation processes, improve existing products or solve current problems in the organization (Lopez et al. 2010; Benbya and Van Alstyne 2010; Gaspoz 2011). In this way, a social innovation community can be built, and the quality of social capital in an enterprise can be improved with the help of internal crowdsourcing (Bharati et al. 2015).

The content of the internal crowdsourcing tasks is determined by the needs of the company and is therefore highly varied. For example, IBM established a platform called ‘InnovationJam’ to drive innovation and collaboration by providing a platform to discuss innovative ideas (Bjelland and Wood 2008). In the InnovationJam platform, the idea creators must first consider concrete aspects such as costs, quality and deadlines, simulate planned projects and then reach the declared goal. After that, every employee gets a virtual wallet and uses their budget to invest in their colleagues’ ideas and vote for them. If the virtual test run is successful, the company decides to follow through with a real implementation.

Similarly, Allianz UK uses an internal crowdsourcing platform to generate as many different ideas as possible while also encouraging the submission of ‘smaller’ ideas, as these are more common in the financial services sector (Benbya and Leidner 2016). Idea generation takes the form of idea campaigns, and the idea campaigns are geared to the needs of the respective area to increase employee participation. Qualitative feedback mechanisms, in particular, ensure that the ideas submitted are treated with respect and provide for a close exchange between the employees who are involved in the process and those responsible for the process of developing the ideas.

Telekom AG has been conducting so-called forecast markets for product innovation since 2012 (Zuchowski et al. 2016). Their platform is accessible to all employees, and, instead of an employee, a department places various topics and problems in the platform. Usually, tasks that are placed in Telekom’s platform, such as sales channels, target groups, benefits analysis, product design or market potential, would be outsourced to external market research agencies. However, due to the short trading time of the questions that have been asked, that is, within 5 working days, results from the forecast markets are available faster and generally exceed the quality of conventional market analyses. The individual contributions by the employees are aggregated into an overall contribution whereby the calculation basis for the forecast is formed from the median of all individual forecasts.

SAP uses internal crowdsourcing to make a social impact and aims to use the ideas of SAP employees to improve the lives of one billion people on the planet by 2020 (Durward et al. 2019). In doing so, SAP technologies should be used to promote sustainable ideas of social significance that are economically feasible at the same time. For this purpose, SAP APJ invests 1 million € annually to finance social start-ups within SAP. The orientation of the foundations focuses mainly on the business areas of health and disaster management.

2.5 Crowdsourcing Forms

Depending on the task characteristics and skill demands, crowdsourcing can generally be divided into two categories: microtask and macrotask crowdsourcing.

Microtask Crowdsourcing

In the case of microtask crowdsourcing, crowdworkers collectively work on a large number of tasks so that the traditional human resource requirements of requesters can be reduced. In doing so, the online crowdsourcing platform splits the big tasks of the requester into small subtasks, which are as small as possible so as to ensure quick and easy processing. This process is then referred to as ‘microtasks’ or ‘micro-jobs’ (Difallah et al. 2015). In the end, all subtasks are brought together again and sent back to the requester. Amazon Mechanical Turk is one of the best-known platforms for this type of activity.

This kind of crowd task is used by requesters to handle less complex, often repetitive, tasks such as image tagging and video tagging or the transcription, translation or digitation of documents that are easy for humans to process but cannot be processed easily by machines (Geiger et al. 2011). However, the task description should contain all the necessary information about the task execution because crowdworkers only see a small portion of a bigger task which they do not know about, and they usually do not have an opportunity to contact the requester for further information about the task (Deng et al. 2016; Felstiner 2011; Leimeister et al. 2016). Therefore, it is extremely important to formulate the task as concretely and specifically as possible to obtain high-quality solutions (Deng et al. 2016).

Macrotask Crowdsourcing

In macrotask crowdsourcing, the task is divided into units that are quite large and therefore still relatively complex and require preprocessing. It is an interactive form of service delivery that is organized collaboratively or competitively and involves a large number of extrinsically or intrinsically motivated actors using modern ICT systems. Among other things, this variant of crowdsourcing uses the principle of the ‘wisdom of crowds’, which James Surowiecki described in his book in 2005 (Surowiecki 2005). It states that the solution achieved and the decision-making are often better when information is accumulated in a heterogeneous group of individuals than when it is given by a single expert. Macrotasks are difficult to take apart, and the solutions for macrotasks require a great deal of sharing of contextual information or dependencies on intermediary results. Therefore, creative tasks such as design contests or coding challenges are executed in the form of macrotasks (Niu et al. 2019).

In contrast to microtask crowdsourcing, macrotask crowdsourcing promotes collaborative working among crowdworkers because of its complex subtasks. Different abilities and skills meet in the crowd and connect productively to one or more end solutions. In this way, both innovation ability, generation and preservation are promoted.

2.6 Process Management

Crowdsourcer

Institutions, e.g. public authorities or universities, non-profit organizations or an individual may act as crowdsourcers (Leimeister and Zogaj 2013). Typically, an organization passes one task on to more than one external crowdworker and uses the results from their work to complete the crowdsourcing process. The ‘crowdsourcer’ (requester, client) usually designs the process by defining the task typology, the required crowdworker profile, the budget and time constraints and by executing the task decomposition. After the task is completed, the crowdsourcer analyses the results based on the predefined evaluation criteria (Difallah et al. 2015) (Fig. 1).

A simple crowdsourcing process (Niu et al. 2019)

Crowdworker

Generally, the crowdworkers consist of an undefined large group of people who have participated in the completion of a given task voluntarily or in return for monetary compensation (Difallah et al. 2015). The optimal number of crowdworkers depends on the type of crowdsourcing task, the task specifications and the information and skills needed to solve the problem (Leimeister and Zogaj 2013). The crowdworkers’ expertise and abilities can determine the quality of the results; therefore the credentials and experience of crowdworkers might play an important role when the requester is selecting the right crowd (Allahbakhsh et al. 2013).

Platform

Crowdsourcing platforms provide the medium of interaction and thus the (only) point of contact between the requesters and the crowdworkers. These platforms control all processes starting with the registration of a crowdworker on the platform, then continuing with the placing of the crowdsourcing task defined by the requester on the platform, assigning of the task to the given crowdworker profile, providing support with technical issues and collecting the answers from the crowdworkers (Difallah et al. 2015). The crowdsourcing platforms can be divided into the following types:

-

Microwork platforms: These platforms are mostly designed for microtask crowdsourcing. These tasks are of low complexity and high granularity. The best-known platforms for microtasks today are Amazon Mechanical Turk, Clickworker and CrowdFlower.

-

Development, test and marketing platforms: Tasks are (very) complex and have low granularity. The best-known platforms for this are rapidusertests and Testbirds.

-

Innovation platforms: Tasks may have both low and high complexity. The best-known platform for this is InnoCentive.

-

Internal crowdsourcing platforms: Tasks are business-driven and may have low or high complexity. There is no generally known platform for internal crowdsourcing; each company uses its own platform or one of the platforms of the external providers.

As explained in chapter ‘Systematization Approach for the Development and Description of an Internal Crowdsourcing System’, the ICU Process and Role Model describes the process of internal crowdsourcing, in particular the individual steps that are necessary to solve an explicit task. Exploiting the full potential of the employees, the following steps should be designed by the requester, usually a department in a company or an employee: (1) impetus; (2) decision; (3) conceptualization; (4) execution; (5) assessment; (6) exploitation and (7) feedback (see chapter ‘Systematization Approach for the Development and Description of an Internal Crowdsourcing System’).

Stage 3 in particular plays an important role in the success of internal crowdsourcing and should be defined before the task execution. The definition, decomposition, integration and allocation of tasks are crucial in this process because the task should be explained unambiguously, in a focused manner and precisely so that employees can understand it easily by reading it in an online environment and so that they can complete the task in a short timeframe (Bailey and Horvitz 2010). Additionally, the bigger picture that lies behind the task should be communicated beforehand so that the employees can understand the context better and feel appreciated by contributing to something bigger (Simula and Ahola 2014). After the task is completed, the results evaluation and the quality control can be performed either by employees in the form of a crowdrating or by the requester (the department or an individual employee) or by an expert in the given domain (Thuan et al. 2017). Another important aspect is that the final results and the next steps with the achieved results should be communicated clearly to the employees.

2.7 Role of IT in Internal Crowdsourcing

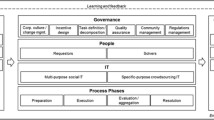

The internal crowdsourcing platforms can be divided into two categories: generic social IT platforms (i.e. multipurpose tools such as social networking sites or wikis) and specific crowdsourcing IT platforms (i.e. tools developed specifically for crowdsourcing, possibly even for a particular purpose in a particular enterprise) (Zuchowski et al. 2016).

Generic Social IT Platforms

In the case of generic social IT platforms, the company uses an internal social platform such as wikis, intranet, yammer or slack as a tool for internal crowdsourcing (Stocker et al. 2012; Rohrbeck et al. 2015). These platforms are established not only for crowdsourcing; it is also easier to reach out to all of the employees in the company by integrating internal crowdsourcing into existing IT infrastructures. Since the employees are already using them and information about how to use the platform is already established, the entry barriers will be low.

However, it can also be challenging if specific IT features are needed to perform the internal crowdsourcing task. Specific IT requirements cannot be implemented in most cases, and the company needs to work with the given IT structure (Rohrbeck et al. 2015). Different user interfaces and new question and data entry types that are not offered by the generic platform cannot be implemented. Also, the other postings regarding the company may distract the attention of the employees, e.g. the most recent internal crowdsourcing task might be shown at the bottom of the webpage because of other postings which lead to lower participation and attention. Furthermore, it is harder to reach out to a specific group of employees if a generic social platform is used.

In addition, security guidelines and regulations (e.g. privacy, barrier-free access) might be a problem in most cases (Rohrbeck et al. 2015). Large companies especially have strict regulations regarding the security and use of companywide IT platforms that can be accessed by a large number of employees. The data shared on the platform might include sensitive data regarding both the company strategy as well as personal information of employees the sharing of which with third-party organizations is not permitted.

Specific Crowdsourcing IT Platforms

Specific IT platforms enable repeatable and well-defined internal crowdsourcing processes that have the same characteristics (Geiger et al. 2011). These platforms can typically be adjusted to the enterprise’s very particular needs, and new IT features can be developed specifically for the particular problem category crowdsourcing is addressing (intelligence, design, decision) (Zuchowski et al. 2016). Having an expert platform that is specifically designed for the company’s own needs might enhance the motivation of employees to participate, since the user experience on such platforms is usually better than on generic social IT platforms for internal crowdsourcing. Moreover, the security and privacy issues can be addressed and designed in line with the company’s requirements. However, maintaining such a platform, developing new features if needed and providing technical support 24/7 are very time-consuming and costly for an enterprise.

Additionally, the entrance barriers for employees are usually higher than a generic platform because of the aversion to ‘yet another platform’. Creating another account and using another tool might be seen as a burden, especially in big corporate organizations, since the employees are already overloaded with the IT tools (Rohrbeck et al. 2015). Another challenge that organizations might face is that the organization itself is constantly changing. Together with this change, the IT requirements for the internal crowdsourcing platform also change, while an IT tool cannot be developed as fast as the change requires. Therefore, a flexible and configurable IT implementation is an important aspect for specific crowdsourcing IT platforms.

For our study, we chose to implement a specific internal crowdsourcing platform because it enhances the effectiveness of internal crowdsourcing in avoiding security and privacy issues and offers the opportunity to adjust the platform to the specific needs of the application partner.

3 An Internal Crowdsourcing Platform: Idealab

Based on the findings in the literature explained earlier, a German energy company, the industry partner, established a specific internal crowdsourcing platform to support innovation activities, promote employee participation in the internal decision processes and identify the undiscovered competencies of its employees. The platform is a white-label version of an external crowdsourcing platform, specifically designed for this industry partner in that it has all the functionalities that an external crowdsourcing platform might have. Before the platform was developed, the strategy, incentive mechanisms and roles in the platform were carefully defined and discussed so that the IT requirements, the technical feasibility of these requirements and their prioritization could be planned and addressed precisely.

At first, the possibilities of IT integration into the industry partner’s IT, the concrete requirements for data protection and intellectual property rights, terms of use, use of pseudonyms, feedback functions of the platform and registration process were discussed and established. The use of the platform is completely voluntarily, and the opportunity to stay anonymous is provided if desired. To protect the internal information in the company and block people who are not an employee of the industry partner, the employees were allowed to register on the platform using only their work email address. When registering, they were asked to fill out the fields for username (it could be their real name or pseudonym), email, password and checkbox asking if they were using their real name. In addition, there were optional fields for age group, gender, the position at the company and the occupation. To inform the employees about privacy and security regulations, the terms of use and unbundling regulations were presented during registration, and employees were asked to accept the conditions of use and unbundling regulations. They were not allowed to create an account without accepting these regulations and filling out the required fields (Fig. 2).

After confirming registration per email, the employees see a landing page where the active tasks (called campaigns) and the results of the past tasks are placed using card user interface design (see Fig. 2). In the first row of the landing page, the active campaigns are listed with a title, short description and remaining duration of the task. A preview of the next active campaigns can be also placed here to inform the employees about the next topics. Following that, the results of past campaigns are displayed in the second row on the landing page (Fig. 3).

In the last row on the landing page, there is relevant information about the platform, rules about the platform use and the internal crowdsourcing activities of other enterprises along with two different kinds of feedback button (see Fig. 3). One of these feedback buttons was designed to collect technical feedback about the platform such as bug reporting, suggestions for new desired features and also general feedback about the campaigns that have been or are being executed on the platform. The other feedback button offers the opportunity to suggest new campaign ideas anonymously and to influence the use and topic direction of the platform together with the employees.

3.1 Data Protection: Privacy and Security

The privacy and security concerns of employees are one of the most important barriers to using the platform. For this reason, special regulations regarding these issues were established during the commissioning of the platform (Rohrbeck et al. 2015; Zuchowski et al. 2016). These regulations were communicated clearly to the employees to win their trust in the platform at every stage of platform use, starting with registration and continuing with active participation.

At first, internal crowdsourcing netiquette was shaped as a code of good behaviour on the platform. To ease online communication, it is suggested that people desist from using abbreviations and capital letters, that the correct sentence structure and spelling be followed, that quotation sources be named and that the already existing contributions be read before participation in order to avoid double contributions. Additionally, the employees were informed that inappropriate posts, e.g. if they deviate significantly from the netiquette or if they make factually untrue statements that could lead to confusion among the workforce, will be removed. Following that, a security and privacy policy was created in line with the European Union General Data Protection Regulation for ‘natural persons’. This includes the following information: sources and data use on the platform, the legal base for the data processing, access to user data, data storage, privacy rights and also the use of cookies.

While using the platform, the IP address of the user, the date and time of the activity, the number of tabs clicked on in the platform and the name of the downloaded files as well as the scope of transmitted data are temporarily stored and used in a log data file. This data is stored for statistical purposes and also to prevent or detect unauthorized access to the platform components. After leaving the platform, this temporary data is deleted. There is no link between any other data from other sources and the personal data of employees. While actively using the platform, in particular, further personal data may be exchanged and stored if the employee uses the feedback buttons or contacts the requesters through other communication channels. However, this happens voluntarily and is based on employee initiative.

Nonetheless, if necessary, the processing of personal data might go beyond the scope that is described above. The reasons for this might be to review and optimize needs analysis procedures, to ensure the IT security and IT operation of the systems, to assert legal claims and provide defence in legal disputes, to prevent crime, to carry out business management measures and to further develop offers and services. As part of the system optimization, key figures about the platform use are recorded and analysed and might include such items as the number of registered users, participants per campaign, cancelled campaigns, help/feedback use and new campaigns. Fully automated decision-making according to data protection law GDPR (including fully automated profiling) is not used on the platform.

The personal data and the data pertaining to employee use of the platform are not disclosed to the industry partner, in order to ensure the full anonymity of employees, unless they want to provide this information. The platform use data and the platform activity data are only made available in an aggregated and anonymized way to the company committees as well as department heads and supervisors. Consequently, no tracking of personal information takes place, thus ensuring employees’ rights of self-determination rights, reinforcing their confidence in the company and creating a trusted corporate culture.

However, the external platform provider has access to this personal data to provide IT support and maintenance, archiving, document processing, call centre services, compliance services, controlling, data destruction, customer management, media technology, website management and accounting services. This data storage is limited to 3 years due to legal limitations. To ensure a high level of usability on the platform, cookies are used for remembering settings between the various visits to the platform, preventing the username and password from having to be entered repeatedly and analysing the use of the platform for further improvements.

3.2 Technical Task Typology

The task typology in internal crowdsourcing differs from external crowdsourcing since the complexity, knowledge and skills of employees and the incentives for participation differ a great deal from those in external crowdsourcing. Moreover, observing the task typologies from the technical point of view leads to a modified version of the task typologies explained in chapter ‘Systematization Approach for the Development and Description of an Internal Crowdsourcing System’. In Idealab, the following task typologies are implemented: info question, free text input, single choice, multiple choice, vote and comment.

In the info question, the task description, the expected input from employees, the campaign initiator, the time schedule and the next steps are explained clearly so that employees can understand the task completely and no direct input from the employees is expected. In the open-ended text question, the employees are asked to write directly their responses to the questions, and their answers are not shown to other employees participating in the campaign. This type of technical question might be used for crowdsolving or crowdcreation if the answers of the participants are to be in full disclosure and creative ideas are desired. In single-choice and multiple-choice questions, the employees answer the questions by choosing one possible offered (single choice) or more than one of the answers offered (multiple choice) from the given list. This kind of question might be used in crowdrating campaigns, where all of the answers are treated equally and combined. Again, the answers given by employees are not shown to the other participants in single-choice and multiple-choice questions.

On the contrary, in the last two question types ‘vote’ and ‘comment’, the participants can see the other answers. In the vote question, employees can vote for an option or options, and every participant sees the aggregated votes for each option while voting. In the comment question, the employees are asked to leave a comment or question describing their ideas in detail using free text input, but their answers are seen by the other employees immediately. This enables a discussion between the participants which might be very helpful in ideation and creation tasks. The differences between these technical task typologies are illustrated in Table 1.

During the design process for an internal crowdsourcing campaign, the requester can select the question types described above and use more than one question type in a single crowdsourcing campaign. In addition to task typologies, the platform has the technical features for limiting the number of participations for an individual employee (max. assignment function), determining the duration of the campaign, limiting the total number of participants and setting conditions using profile keys to address the targeted group of employees if necessary. All the question types can be styled using HTML, and multimedia such as video, picture or documents can be added to the question descriptions.

3.3 Roles and Tools for Platform Management

Along with the roles defined in chapter ‘Systematization Approach for the Development and Description of an Internal Crowdsourcing System’, an internal crowdsourcing platform needs additional roles such as crowd master, crowd technology manager and campaign master as well as a second technical platform, a dashboard, for the micromanagement of internal crowdsourcing tasks. Figure 4 shows the roles and their relationship to each other in an internal crowdsourcing environment.

The campaign owner might be an employee of the company who is assigned to manage the communication between the content owners, the crowd and the crowd technology manager. It is an objective position where the crowd master aims to create a free and fair internal crowdsourcing environment for employees and to provide solutions to the problems of campaign masters by designing an optimal internal crowdsourcing campaign. In addition to these, the campaign owner communicates all the technical problems regarding the platform and desired new features if necessary. During the course of platform management, we found out that a dashboard would be very beneficial to help the crowd technology manager micromanage the internal crowdsourcing tasks. These tasks might include creating new tasks, prolonging the duration of a task, making some text or style changes on active tasks, observing the answers and deleting the answers that violate the netiquette rules or other internal company regulations, activating or deactivating tasks or observing and reporting platform statistics.

4 Empirical Results: Case Studies

The platform was released in June 2018, and 11 different campaigns were realized between its release and October 2019. The communication of new campaigns, campaign results and news regarding the platform was carried out by the crowd master using the company’s intranet, yammer and sending email newsletters to the registered user of the platform when there were new campaign releases, campaign results releases or news regarding the platform.

According to the latest figures provided by the industry partner, 1820 people are employed by the company. Out of 1820, 535 employees have registered on the platform with a registration ratio of 29.4%, which is quite high for a voluntary platform. After the release of each new campaign, an email newsletter and a post in internal communication channels were sent. In total, 11 different campaigns were released, and the number of participants on the platform has increased after each campaign release, as shown in Fig. 5. Additionally, out of a registered 535 users, 360 employees have voluntarily specified the information about their age group, gender, position and occupation at the company, and 50.8% of the employees have used their real names during the registration. This shows that the opportunity to use a pseudonym is an important feature from the employee’s perspective. The campaign participants were mostly young employees working in governance or sales, with an almost equal number of males and females, as shown in Fig. 6. Surprisingly, employees over 40 years old were relatively active on the platform. However, employees with a management position were not as interested as employees without a management role.

Figure 7 shows the total work duration on the platform including all the answers completed for 11 campaigns. More than half of the contributions were done in under 160 s ~ 2.67 min, and the average work duration was 351 s ~ 5.85 min. Although the campaign complexity and durations vary a lot, this is not reflected in the average work duration because employees have chosen to participate mostly in short tasks and are not interested in long complex tasks.

Table 2 displays the detailed participation statistics regarding 11 campaigns that were executed after the release of the platform. The campaigns are listed and numbered by release time, whereby they are categorized into four different topics: location, product, QA and survey. The technical task typologies used and the number of questions in each campaign are listed next to each other. The ‘average work duration’ column shows the average completion time in seconds per campaign. Next to it, the ‘started tasks’ column presents the number of task started without completing the task, meaning that employees did not proceed through to completion, although they clicked on the campaign and read the campaign description.

In some campaigns, employees were allowed to participate more than once, so the total number of submitted answers might be higher than the number of unique participants. To differentiate between these two figures, the ‘completed tasks’ column presents the overall number of submitted answers without differentiating the uniqueness of the participants, and the ‘unique users’ column shows the number of unique participants in campaigns. To measure the achievement of a campaign, we introduced the ‘participation ratio’, which illustrates the task completion based on the number of registered users on the platform by the time of campaign release. Since the number of participants has increased over time, the absolute number of participants is not sufficient to describe the success of a campaign. The average participation ratio on the platform was 19.69%, with campaign number 5 having the highest participation ratio of 51.94%.

Another ratio that we introduced is the ‘task completion ratio’. It helps to understand how many of the users continue and finish the campaign after starting it and how many read the campaign description. The 11 campaigns were started a total of 2,875 times but only completed 564 times, which results in an average task completion ratio of 19.62%, with campaign number 5 having the highest task completion ratio of 47.52%.

Analysing the results by topics, the first topic contains all the campaigns related to the relocation of the industry partner employees to another building, called ‘location’. In the context of the location topic, five different campaigns were released, and this topic was the most interesting in the platform with an average participation ratio of 27.25% and a task completion ratio of 26.86%. It was realized using only the comment and vote functions of the platform, meaning all the answers or rather results were directly shown to the participants. Additionally, the number of questions was one in four of the campaigns and four in one of the campaigns, leading to lower expected workload measured in time.

The second topic, called the ‘product’, contains all the campaigns related to the product, e.g. further development of an existing product, collecting new product ideas or collecting feedback about the existing product. In the context of the product, three campaigns were released and completed with an average participation ratio of 10.04% and an average task completion ratio of 17.58%, both lower than the ratios in the location topic. The campaigns contained multiple questions in the form of a single-choice, multiple-choice and open-ended questions. The reason for lower participation might be the higher expected workload because the average number of questions in campaigns was 10.3 and average work duration approx. 11 min, which are above the platform’s overall average.

The third topic, called ‘QA’, is about campaigns that provide employees with the opportunity to ask questions or leave comments about the current issues in the company or to ask any question directly to the top management of the company. In the context of the QA topic, two different campaigns were released, and both campaigns contained one question in the comments. The average participation ratio was 6.43%, lower than the location topic, and the average task completion ratio was 6.03%. Although the expected workload measured in time was not so high, the participation ratio is quite a bit lower than the location topic. The low task completion ratio also shows that the number of started tasks was high, meaning that the employees were generally interested in this topic, but they did not want to participate although every contribution was stored anonymously. This shows the effect of the selected topic on participation and also shows that sensitive topics such as asking a question to the manager are quite interesting but perceived as being risky.

The last topic, called ‘survey’, contains one campaign which had two questions in multiple-choice format. The participation ratio was 28.87% and the task completion ratio 20.1%, similar to the location topic. This was the first campaign released on the platform, and the expected workload was low; therefore the participation ratio is quite high in comparison to the QA and product topics.

For further investigation, the campaigns are analysed based on two categories: topic and technical task typology. As shown in Table 2, the campaigns with task IDs 2, 5, 8, 9 and 10 belong to the topic location; with task IDs 3, 6 and 7 to the product topic; with task IDs 4 and 11 to the QA topic and with task ID 1 to the topic survey. For categorizing the technical task typologies, the campaigns with the technical task typologies single choice and multiple choice are considered as one category and called ‘selection’. Campaigns with task IDs 1, 3, 6 and 7 belong to this category. The campaigns with task IDs 2, 4, 8, 9 and 11 belong to the technical task typology ‘comment’ and with task IDs 5 and 10 to ‘vote’.

4.1 Work Duration and Participation

Figure 8 illustrates the boxplots of work duration categorized by topic (left) and technical task typology (right). Because of the non-normal distribution of the data, the Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted to find out differences between topics and task typologies in terms of working duration. There was a statistically significant difference (Chi-square = 85.511, p = 0.000, df = 3) among the four different categories of topics (location, product, QA, survey) regarding the work durations. The post hoc test (Dunn criterion) revealed that the mean of product (M = 745.12) was significantly higher than the mean of survey (M = 163.90, p < 0.05) and higher than the mean of location (M = 238.97, p < 0.01). A second Kruskal–Wallis test showed that there were also significant differences (Chi-square = 49.095, p = 0.000, df = 2) among the categories of technical task typologies (selection, comment, vote). The post hoc test (Dunn criterion) revealed that the mean of vote (M = 182.53) was significantly lower than the mean of comment (M = 529.91, p < 0.01) and lower than the mean of selection (M = 511.49, p < 0.05).

Furthermore, the Spearman rank-order correlation coefficients are calculated to investigate the relationship between the average work duration in seconds and the participation (N = 11). There was a moderate negative significant correlation between the average work duration and completed tasks (rs = –0.618, p = 0.043). This result confirms that the higher average work duration gets, the lower the number of completed tasks will be. The Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient between average work duration and the participation ratio shows a substantial trend towards significance with p = 0.060 and is negative with a moderate value of rs = –0.582. Figure 9 illustrates this relationship in a regression plot.

4.2 Participation Day and Time

As shown in Fig. 10, the time of the day when participation takes place is mostly in the early mornings between 8 and 10 (N8–10 = 197), and the most popular day is in the middle of the week, Wednesday and Thursday (Nwednesday = 141, NThursday = 130). This is a good indication of what time to publish an internal crowdsourcing campaign on the platform and when to announce it to the employees. Looking at the descriptive statistics, late Friday afternoons after 4 pm is not an optimal time to release a new crowdsourcing campaign on the platform.

To see if this pattern is applicable for all the categories of topic and technical task typology, Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted. No significant differences were found between the four categories of topic (Chi-square = 5.025, p = 0.170, df = 3) and between the three categories of technical task typology (Chi-square = 5.470, p = 0.065, df = 2) regarding the participation time of the day. Similarly, there was no significant difference between the four categories of topics (Chi-square = 0.901, p = 0.825, df = 3) and the three categories of technical task typology (Chi-square = 1.691, p = 0.429, df = 2) regarding the day of participation.

4.3 Predicting the Participation

Multiple linear regression was carried out to investigate whether average work duration, number of questions, topic and task typology of each campaign could significantly predict the number of completed tasks per campaign. The results of regression showed that the model explained 77.8% of the variance and that the model was a significant predictor of completed task number, F (4, 6) = 5.265, p = 0.036. While task typology contributed significantly to the model (p = 0.036), average work duration (p = 0.112), topic (p = 0.862) and number of questions (p = 0.377) did not. The final predictive model was:

The task typology being the only significant predictor of the model was the strongest contributor to the model. Therefore, for further investigation of task typology, we carried out curve fitting and compared linear, logarithmic, inverse, quadratic, cubic, power, compound, S-curve, logistic, growth and exponential models based on their relative goodness of fit where the number of completed tasks is predicted by task typology. The results revealed that the quadratic and cubic models are the best fitting significant models with R2 = 0.895 and p = 0.000 for both models. Figure 11 illustrates the different curve fittings for task typology.

Since a better portion of the variance in the number of completed tasks is explained by the quadratic model of task typology, quadratic regression was carried out to finalize the model coefficients. The results showed that the model explained 89.5% of the variance and that the model was a significant predictor of completed task number, F (2, 8) = 34.253, p = 0.000, and task typology also contributed significantly to the model (p < 0.05). The final predictive model was:

5 Discussion

This chapter has analysed the use of internal crowdsourcing from the IT perspective based on the empirical results of the successful implementation of different kinds of internal crowdsourcing campaigns.

Our findings from the active use data of the internal crowdsourcing platform show that there is a general interest in using the platform proven by the relatively high registration ratio for a voluntary platform, although no specific incentive mechanisms or programmes were implemented. The only motivation to participate in the platform comes from enjoyment in the activity or the chance to shape products according to one’s own wishes. This puts a specific emphasis on the topics to be selected for internal crowdsourcing campaigns on the platform. Therefore, the needs and wishes of the employees should be asked and considered while choosing and shaping crowdsourcing tasks. What is more, the number of registered users increased after the release of each campaign because of the active marketing of new campaigns via newsletters, intranet and yammer. This shows how important it is to communicate and actively promote the platform.

Looking at the profile of registered users, we observed that mostly young employees without a management role preferred to participate on the platform, which is a common pattern for new technologies introduced to companies, because technology affinity decreases with age. As a solution to this problem, onsite courses about how to use the platform could be given by the company. Following on from this, looking at the absolute number of started tasks and completed tasks in each campaign, we observed that the interest in starting a campaign was always high, while the task completion ratio was quite low in some cases. The reason for this might be the uninteresting topic, complex task design or employees being distracted by their daily tasks, which in most cases have higher priority.

In terms of participation ratio and task completion ratio, the most successful campaign was about voting on the name of the company’s new building (ID 5). This is a perfect example of a successful task design and topic selection, because it was relevant for every employee in the company, easy to complete in under 3 min and the idea of naming the industry partner’s new building motivated the employees intrinsically. As such, three important aspects of an internal crowdsourcing task—optimal duration, low complexity and interesting topic—were met in that way.

Furthermore, the findings about significant different average work durations between three technical task typologies could help by estimating the expected work duration and consequently optimizing the task design, as the average work duration negatively affects the number of completed answers. This shows that the employees of the industry partner are mostly interested in short tasks. If this is already known about employees, then complex tasks such as ideation, innovation or technical challenges might not be the right topic selections for this type of employee group, as these usually require longer timeframes to be completed.

Another important empirical finding was about the time and day of participation. The employees mostly preferred to participate in the middle of the week and early in the morning between 8 and 10, and they tended not to participate on Friday afternoons. There was also no difference in different kinds of topics or task typologies regarding the participation day and time. So, the optimal time for releasing all kinds of new campaigns would be Wednesdays in the early mornings, while Friday afternoons should be avoided.

Next, we tried to predict the number of participants based on the data that was available before releasing the campaign, e.g. work duration, topic, task typology and the number of questions. The most important factor is again task typology, explaining the variance in participation of up to 90% with a quadratic regression model. Apparently, task typology is the determining factor for the success of an internal crowdsourcing campaign and should be selected very carefully. Based on these findings, the crowd manager could estimate the expected number of completed tasks and accordingly predict the success of a crowdsourcing campaign in terms of participation.

6 Conclusion

In this chapter, we tried to find out empirically which kind of internal crowdsourcing task is desired by the employees. Although the scope of campaigns and variation of topics and typologies were limited, some preliminary results regarding the optimal work duration, ideal task typology and interesting topics could be found out.

The most important finding is that how interesting the internal crowdsourcing campaign is with respect to the intrinsic motivation of the employees determines the success of a campaign. Therefore, before introducing such a platform into a company, conducting surveys regarding the desired topics and motivating factors could help to select optimal topics. In addition to that, the task typology played an important role while predicting participant numbers, because indirectly the task typology determines the expected work duration. Therefore, the reasons for the desired low work duration should be investigated in detail. This might be due to the company culture: the company might not accept the time spent on internal crowdsourcing as working time, or other daily tasks might have a higher priority, or it might have to do with the general preference of employees. If the corporate culture limits the working duration, then special time slots for spending time on the platform could be defined.

Companies must understand how they can design and use an internal crowdsourcing system technically and from the employee’s perspective (Fitzgerald and Stol 2015) so that the potential of internal crowdsourcing can be used effectively. To our knowledge, this study is the first to address this gap by summarizing and deriving requirements for the implementation of an internal crowdsourcing system comprehensively considering the privacy and security concerns of employees, company intern regulations regarding crowdwork and the technical aspects of an internal crowdsourcing task.

Concerning the limitations of the study, they are mainly due to the fact that the empirical investigation involved only 11 crowdsourcing campaigns with a narrow scope of topics and task typologies performed by a single company; thus, results are not generalizable, since corporate culture plays an important role in the preferences of employees regarding topics, task typologies and work duration. However, the aim of the study was not to provide a complete picture about the issue under analysis but to derive some preliminary insights that can provide some impulses to scholars and professionals and open the way to further research.

References

(2017) Daimler 2017: Daimler and the transformation of the automotive industry. 29 March. Accessed 18 Oct 2019. https://www.daimler.com/documents/investors/annual-meeting/daimler-ir-amspeechzetsche-2017.pdf

Allahbakhsh M, Benatallah B, Ignjatovic A, Motahari-Nezhad HR, Bertino E, Dustdar S (2013) Quality control in crowdsourcing systems: Issues and directions. IEEE Internet Comput 17(2):76–81

Bailey BP, Horvitz E (2010) What’s your idea?: a case study of a grassroots innovation pipeline within a large software company. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems

Benbya H, Leidner D (2016) Harnessing employee innovation in internal crowdsourcing platforms: Lessons from Allianz UK. In: Thirty seventh international conference on information systems. AIS, Dublin

Benbya H, Leidner D (2018) How Allianz UK used an idea management platform to harness employee innovation. MIS Q Exec 17(2):141–157

Benbya H, Van Alstyne MW (2010) How to find answers within your company. MIT Sloan Research Paper

Bharati P, Zhang W, Chaudhury A (2015) Better knowledge with social media? Exploring the roles of social capital and organizational knowledge management. J Knowl Manag 19(3):456–475

Bjelland OM, Wood RC (2008) An inside view of IBM’s ‘Innovation Jam’. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 50(1):32

Blohm I, Jan Marco L, Zogaj S (2014) Crowdsourcing and crowd work—Ein Zukunftsmodell der IT-gestützten Arbeitsorganisation? In: Wirtschaftsinformatik in Wissenschaft and Praxis. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 51–64

Brabahan D (2008) Crowdsourcing as a model for problem solving. Int J Res New Media Technol 14(1):75–90

Brabham DC (2013) Crowdsourcing. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Deng X, Joshi KD, Galliers RD (2016) The duality of empowerment and marginalization in microtask crowdsourcing: Giving voice to the less powerful through value sensitive design. MIS Q 40(2):279–302

Difallah DE, Catasta M, Demartini G, Ipeirotis PG, Cudré-Mauroux P (2015) The dynamics of micro-task crowdsourcing: The case of amazon mturk. In: Proceedings of the 24th international conference on world wide web

Durward D, Simmert B, Peters C, Blohm I, Leimeister JM (2019) How to empower the workforce-analyzing internal crowd work as a neo-socio-technical system. In: Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii international conference on system sciences

Erickson LB, Trauth EM, Petrick I (2012) Getting inside your employees’ heads: Navigating barriers to internal-crowdsourcing for product and service innovation. In: Thirty third international conference on information systems, Orlando

Felstiner A (2011) Working the crowd: employment and labor law in the crowdsourcing industry. Berk J Employ Labor Law 32:143

Fitzgerald B, Stol K-J (2015) The dos and dont’s of crowdsourcing software development. In: International conference on current trends in theory and practice of informatics

Franke N, Klausberger K (2010) Die Architektur von Crowdsourcing: Wie begeistert man die Crowd. Crowdsourcing: Innovations management mit Schwarmintelligenz 1:58–71

Gadiraju U (2018) Its getting crowded! Improving the effectiveness of microtask crowdsourcing. Gesellschaft für Informatik eV.

Gaspoz C (2011) Prediction markets as web 2.0 tools for enterprise 2.0. In: AMCIS 2011

Geiger D, Seedorf S, Schulze T, Nickerson RC, Schader M (2011) Managing the crowd: towards a taxonomy of crowdsourcing processes. In: Proceedings of the seventeenth Americas conference on information systems, Detroit

Geiger D, Rosemann M, Fielt E, Schader M (2012) Crowdsourcing information systems-definition typology, and design. In: Thirty third international conference on information systems, Orlando

Hammon L, Hippner H (2012) Crowdsourcing. Bus Inform Syst Eng 4(3):163–166

Hirth M, Hoßfeld T, Tran-Gia P (2012) Analyzing a commercial microtask crowdsourcing platform from the involved actors’ viewpoints. EuroNF Summer School, Würzburg

Hoßfeld T, Hirth M, Tran-Gia P (2012) Aktuelles Schlagwort: Crowdsourcing. Informatik Spektrum 35(3):204–208

Howe J (2006) The rise of crowdsourcing. Wired Mag 14(6):1–4

Howe J (2009) Crowdsourcing: Why the power of the crowd is driving the future of business (unedited ed). Crown Business

Kittur A, Smus B, Khamkar S, Kraut RE (2011) Crowdforge: Crowdsourcing complex work. In: Proceedings of the 24th annual ACM symposium on user interface software and technology. ACM. pp 43–52

Kittur A, Nickerson JV, Bernstein M, Gerber E, Shaw A, Zimmerman J, Lease M, Horton J (2013) The future of crowd work. In: Proceedings of the 2013 conference on computer supported cooperative work. ACM, pp 1301–1318

Leimeister JM, Zogaj S (2013) Neue Arbeitsorganisation durch Crowdsourcing: Eine Literaturstudie. Arbeitspapier, Arbeit and Soziales

Leimeister JM, Zogaj S, Durward D (2015) New forms of employment and IT crowdsourcing. In: 4th conference of the regulating for decent work network

Leimeister JM, Durward D, Zogaj S (2016) Crowd Worker in Deutschland: Eine empirische Studie zum Arbeitsumfeld auf externen Crowdsourcing-Plattformen. Study der Hans Böckler-Stiftung

Lopez M, Vukovic M, Laredo J (2010) Peoplecloud service for enterprise crowdsourcing. In: 2010 IEEE international conference on services computing

Lüttgens D, Pollok P, Antons D, Piller F (2014) Wisdom of the crowd and capabilities of a few: internal success factors of crowdsourcing for innovation. J Bus Econ 84(3):339–374

Malhotra A, Majchrzak A (2014) Managing crowds in innovation challenges. Calif Manag Rev 56(4):103–123

Malhotra A, Majchrzak A, Kesebi L, Looram S (2017) Developing innovative solutions through internal crowdsourcing. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 58(4):73

Meffert H, Burmann C, Kirchgeorg M, Eisenbeiß M (2018) Marketing: Grandlagen marktorientierter Unternehmensführung Konzepte—Instrumente—Praxisbeispiele. Springer

Niu X-J, Qin S-F, Vines J, Wong R, Hui L (2019) Key crowdsourcing technologies for product design and development. Int J Autom Comput 16(1):1–15

Otte A, Schröter W (2018) Lebende Konzernbetriebsvereinbarung als soziale Innovation. 30 July. Accessed 20 Oct 2019. http://www.blog-zukunft-der-arbeit.de/wpcontent/uploads/2018/07/Lebende_KBV_Otte_Schroeter.pdf

Rohrbeck R, Thom N, Arnold H (2015) IT tools for foresight: The integrated insight and response system of Deutsche Telekom Innovation Laboratories. Technol Forecast Soc Change 97:115–126

Simula H, Ahola T (2014) A network perspective on idea and innovation crowdsourcing in industrial firms. Ind Market Manag 43(3):400–408

Sixt E (2014) Schwarmökonomie and Crowdfanding: Webbasierte Finanzierungssysteme im Rahmen realwirtschaftlicher Bedingungen. Springer

Stocker A, Richter A, Hoefler P, Tochtermann K (2012) Exploring appropriation of enterprise wikis. Comput Support Cooper Work (CSCW) 21(2-3):317–356

Surowiecki J (2005) The wisdom of crowds. Anchor

Thuan NH, Antunes P, Johnstone D (2017) A process model for establishing business process crowdsourcing. Australas J Inform Syst 21

Valentine MA, Retelny D, To A, Rahmati N, Doshi T, Bernstein MS (2017). Flash organizations: crowdsourcing complex work by structuring crowds as organizations. In: Proceedings of the 2017 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems. ACM, pp 3523–3537

Vel V, Park I, Liu J (2018) The effect of enterprise crowdsourcing systems on employees’ innovative behavior and job performance. In: Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii international conference on system sciences, Hawaii

Zuchowski O, Posegga O, Schlagwein D, Fischbach K (2016) Internal crowdsourcing: conceptual framework, structured review, and research agenda. J Inform Technol 166–184

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Iskender, N., Polzehl, T. (2021). An Empirical Analysis of an Internal Crowdsourcing Platform: IT Implications for Improving Employee Participation. In: Ulbrich, H., Wedel, M., Dienel, HL. (eds) Internal Crowdsourcing in Companies. Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52881-2_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52881-2_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-52880-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-52881-2

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)