Abstract

The phenomenon of crowdsourcing is increasingly being addressed in academic literature. Companies utilize crowdsourcing to search for solutions to internal problems outside of the companies’ boundaries, accessing the vast and diverse knowledge and creativity of people all over the world. More recently, a growing interest has emerged that concentrates on the intra-organizational application of this phenomenon—internal crowdsourcing. While conventional internal innovation activities are mostly concentrated within a few dedicated departments, this new approach helps companies to open up their innovation process to all employees. Internal crowdsourcing can help companies bridge geographical distances, integrate new employees, predict the market success of products, and create ideas for new businesses.

This chapter aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the existing empirical findings regarding the management of internal crowdsourcing. In this review, 27 papers, covering more than 100 companies, are analysed. They are based on more than 800 interviews, participant observations, action design research, surveys, and datasets of internal innovation contests. The results of this review will help practitioners to design the management of internal crowdsourcing based on existing implementations and lessons learned, helping them to unleash the full innovation potential of their employees, creating a valuable competitive advantage.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Crowdsourcing

- Internal crowdsourcing

- Corporate crowdsourcing

- Governance

- Management

- Innovation

- Knowledge

- Literature review

1 Introduction

To ensure long-term competitiveness and withstand increasing global competition, strategic innovation activities are becoming increasingly important. In their search for innovative ideas, companies are relying more and more on the principle of crowd wisdom (Surowiecki 2004). If internal company problems are solved by an undefined external crowd of people via the Internet, this is referred to as crowdsourcing (Howe 2006). The idea is to use an Internet platform to bring together internal problems and external knowledge in order to generate new solutions.

In the recent past, this approach has been internalized by firms and has received considerable academic interest (Erickson et al. 2012; Zuchowski et al. 2016; Benbya and Leidner 2018). Several well-known companies like Siemens, McKinsey & Co., Eli Lilly (Benbya and van Alstyne 2011), Allianz (Benbya and Leidner 2018), Deltares (Leung et al. 2014), Deutsche Telekom (Rohrbeck et al. 2015), IBM (Bjelland and Wood 2008), Microsoft (Bailey and Horvitz 2010), and NASA (Davis et al. 2015) have already been reported as having implemented internal crowdsourcing. Companies use internal crowdsourcing to access the knowledge of the entire workforce, identifying solutions to problems and accessing innovative ideas that might not have arisen within a traditional R&D department (Simula and Ahola 2014). Multinational corporations with a large number of geographically dispersed employees in particular can use this technology to overcome information silos, using the full potential of the company crowd more effectively and efficiently (Malhotra et al. 2017; Majchrzak et al. 2009; Dimitrova and Scarso 2017). Supported by an intranet- or Internet-based platform, employees from various company divisions can connect, share ideas, and work collaboratively. The most comprehensive definition of internal crowdsourcing to date can be found in Zuchowski et al. (2016). Based on a structured literature review, a consistent definition was created, relying on 74 academic articles on internal crowdsourcing. As a result, internal crowdsourcing is defined as an ‘IT-enabled group activity based on an open call for participation in an enterprise’ (Zuchowski et al. 2016, p. 168).

Compared to external crowdsourcing, internal crowdsourcing has some important advantages. It allows the parameters of idea competitions to be set in a comparatively broad manner (Leung et al. 2014). Further, employees often have implicit knowledge, in particular about customers, products, and services that are not inherent in external crowds (Henttonen et al. 2017; Malhotra et al. 2017). Internal crowdsourcing can be used to encourage entrepreneurial skills (Leung et al. 2014) and can help employees to gain a broader awareness for their ideas within the company (Malhotra et al. 2017), potentially leading to more committed employees (Rao 2016; Malhotra et al. 2017). Hence, it helps to create a more open innovation culture, allowing for more collaboration and participation (Scupola and Nicolajsen 2014). It also potentially helps huge companies to connect their existing employees with one another and to integrate new ones (Majchrzak et al. 2009). Further, Rohrbeck et al. (2015) found that it positively impacts knowledge management. Stieger et al. (2012) show that internal crowdsourcing can be used to support employee involvement in strategy dialogues.

To fully leverage the positive impacts and potential competitive advantages of internal crowdsourcing, it is of paramount importance to understand, coordinate, and optimally implement its governance tasks (Pedersen et al. 2013; Zuchowski et al. 2016; Smith et al. 2017). Governance tasks in this context are understood as the totality of all activities and strategies to control the internal crowd as well as the entire crowdsourcing process (Zuchowski et al. 2016). However, Wedel and Ulbrich (see this chapter) argue that governance, due to its prior utilization in the sphere of political science, might be a slightly misleading terminology. Instead, they propose the use of ‘management of crowdsourcing’. We follow their argumentation and will refer to management instead of governance in the following. For more information, see this chapter.

Although quite extensive literature on external crowdsourcing exists, internal crowdsourcing is much less researched (Zuchowski et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2016). Due to the inherent structural differences between the two concepts, one can, unfortunately, not readily draw from existing knowledge on external crowdsourcing (Knop et al. 2017). As an example, this has been confirmed for the perceived importance of different rewards for participation in crowdsourcing in external and internal crowdsourcing scenarios (Muhdi and Boutellier 2011).

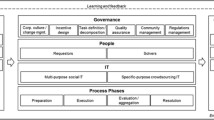

This study aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the existing empirical findings regarding the management of internal crowdsourcing. To do so, the recently published governance framework for internal crowdsourcing by Zuchowski et al. (2016), which relies on previous work by Pedersen et al. (2013) and Zogaj and Bretschneider (2014), is used to structure this review. Based on a structured literature review, the authors developed a conceptual framework that will help us to meaningfully describe the management tasks of internal crowdsourcing. The proposed framework consists of six different components:

-

1.

Corporate culture and change management

-

2.

Incentive design

-

3.

Task definition and decomposition

-

4.

Quality assurance

-

5.

Community management

-

6.

Regulations and legal implications

This study relies only on empirical academic papers that are based on primary information sources. Hence, theoretical deliberations and derivatives of other forms of internal idea markets that could be relevant for this study are not used here. In total, 27 papers that reported empirical findings and contained relevant information on at least one of the six dimensions of the chosen framework were found and analysed. These contributions cover more than 100 companies and are based on more than 800 interviews, participant observations, actions design research, surveys, and the datasets of internal idea contests.

Based on the management tasks introduced above and the analysed literature, the present chapter provides insights into the following research question: how do the observed companies optimally design their management to implement internal crowdsourcing successfully? As internal crowdsourcing is not yet a widely adopted approach to source knowledge and ideas from employees (Stieger et al. 2012; Zhu et al. 2016, 2019), the findings of this chapter contribute to understanding the determinants of successful internal crowdsourcing implementations. This will provide a resource that companies willing to incorporate internal crowdsourcing can use to adequately transform their management. Consequently, this chapter will help companies to unleash the full innovation potential of their employees, creating a valuable competitive advantage.

This study is structured as follows. First, the methodology applied in this study is described. Following that, the synthesis of the existing empirical academic literature is presented. Finally, a summary of the most critical aspects is provided.

2 Methodology

As described above, the management tasks introduced in Zuchowski et al. (2016) are used as a categorization scheme to structure the literature review. The methodology is following the approach towards conducting a literature review as described by Webster and Watson (2002).

For the literature review at hand, the ScienceDirect, Scopus, EBSCO Business Host, SpringerLink, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases were accessed and searched. The keywords chosen covered different synonyms for internal crowdsourcing (corporate crowdsourcing, intra-organizational crowdsourcing, internal collaboration innovation, employee idea platform, enterprise crowdsourcing, internal crowdsourcing, crowdsourcing company, employee crowdsourcing). Additionally, backward and forward reference searching was conducted to identify additional relevant studies.

The inclusion decision process was as follows: First, after deleting duplicates, articles not published in peer-reviewed journals or conference proceedings were excluded. Second, articles that do not explicitly or implicitly deal with the concept of internal crowdsourcing were excluded. Third, articles were rejected if they do not address at least one component related to the management of internal crowdsourcing (see above). Lastly, to be included, the articles must contain a contribution on how to manage internal crowdsourcing based on the empirical analysis of primary data.

Of all articles, 27 relevant contributions have been identified and included in the present analysis. Table 1 contains a list of the 27 papers, their authors, and titles, as well as the primary data they are based on, if available. Their individual relevance to the discussion of each of the management tasks is depicted in Table 2. The selected articles cover more than 100 firms and are based on more than 800 interviews, participant observation, actions design research, surveys, and datasets of idea contests. Thus, the present study relies on various implementations of internal crowdsourcing in a variety of contextual settings—including sector, company size, company age, employee composition, etc. As a result, the description of the phenomenon is based on a range of different settings that allow contradictions and consensuses between the analysed case studies to be revealed. In the next section, the findings of all case studies with respect to the six management components will be reported.

3 Synthesis of the Literature

3.1 Corporate Culture and Change Management

Managing corporate culture and the changes that can be triggered by internal crowdsourcing is a significant challenge that does not exist in external crowdsourcing (Denyer et al. 2011). This involves creating an open and collaborative corporate culture in which internal crowdsourcing can function optimally (Simula and Vuori 2012; Steinhuser et al. 2011; Stocker et al. 2012). Internal crowdsourcing can help to break down hierarchical structures in companies and enable communication on equal terms (Riemer et al. 2015; Scupola and Nicolajsen 2014). However, not only hierarchical structures are questioned, but also well-established project-based innovation processes, since such platforms tackle innovation within a company in a much more open and informal manner, which is particularly important and challenging for larger companies (Scupola and Nicolajsen 2014). Internal crowdsourcing calls for a move towards open and transparent structures, which can only be achieved through active change management (Abu El-Ella et al. 2013; Riemer et al. 2012a).

Steinhuser et al. (2011) define specific requirements for ‘Enterprise 2.0 Readiness’: open communication culture, availability of resources, willingness to share knowledge, extroversion, education, and responsibility. A lack of openness to ideas from other departments could lead, for example, to employees not recognizing ideas from other departments—the not-invented-here syndrome (Lüttgens et al. 2014). Arena et al. (2017) call this environment an adaptive space. Within this space, ideas, people, and information can move freely across the organization. Employees’ ideas must be accepted and valued, which can be communicated, for example, through timely feedback (Boudreau et al. 2011; Henttonen et al. 2017; Simula and Vuori 2012). Support and buy-in from top management are seen as particularly important (Lüttgens et al. 2014; Benbya and Leidner 2018; Pohlisch 2019). Management should utilize a proactive leadership style, promote participation in crowdsourcing, create incentive structures, and ensure a sufficient provision of resources (Erickson et al. 2012). This does not simply mean that management approves the project plan and the budget for the implementation of a crowdsourcing project. Instead, in addition to approving investments, it is vital to obtain general support from various business units that should have the capacity and ability to subsequently adopt and integrate the results (Ooms et al. 2015; Pohlisch 2019). Additionally, it seems that internal crowdsourcing approaches that were initiated bottom-up received high recognition and acceptance, hinting that top management should be aware of and support such endeavours (Pohlisch 2019).

Furthermore, executive leadership should concentrate on setting policy, promoting flexibility, and ensuring liquidity inside the internal crowdsourcing system (Benbya and van Alstyne 2011). In line with this argument, Stieger et al. (2012) report that, while active communication of management with idea owners (e.g., by commenting) increased participation, this form of engagement can easily distract management from other tasks. Nevertheless, sufficient resources seem to be the prevailing bottleneck, which has been reported as being particularly important for non-product-carrying units, as they usually have smaller R&D budgets to begin with (Smith et al. 2017). To overcome the problem of reaching a critical mass, management could seed the market with ideas and subsidize the creation of key knowledge (Benbya and van Alstyne 2011).

To sustain the capabilities of internal crowdsourcing, one idea would be to install a dedicated team, responsible for promoting and adjusting the system (Benbya and Leidner 2018; Elerud-Tryde and Hooge 2014; Stieger et al. 2012). Benbya and Leidner (2018) describe how an innovation champion can promote internal crowdsourcing practices in their working environment as well as with senior management and provide coaching and mentoring for participating colleagues. Ulbrich and Wedel (see chapter ‘Systematization Approach for the Development and Description of an Internal Crowdsourcing System’ of this book) argue that additional roles must be considered to manage internal crowdsourcing successfully. In building their model, they introduce primary, secondary, and tertiary roles which employees can take on. In total, they describe eight different roles with specific duties and functions: (1) Crowd Master, (2) Campaign Owner, (3) Crowd Technology Master, (4) Content Owner, (5) Secondary Counterpart, (6) Crowd, (7) Executive Board, and (8) Employee Union Representation. This framework can help companies to unambiguously attribute necessary functions to suitable employees, reducing the risk of overlapping competencies and preventing potential conflicts. For a more detailed description of the role model for internal crowdsourcing and the corresponding descriptions of the roles, see Ulbrich and Wedel (see chapter ‘Systematization Approach for the Development and Description of an Internal Crowdsourcing System’ of this book).

To raise awareness for such a system, it is vital to communicate its advantages and opportunities throughout the company. In order to achieve this, the management could use newsletters, workshops, and lecture series with internal and external speakers (Davis et al. 2015). Stieger et al. (2012) further report the use of introduction videos, posters, flyers, and particularly on-site presentations to increase awareness. Direct superiors in particular should be encouraged to inform employees about the possibilities to participate. Employees often do not even know what crowdsourcing initiatives and opportunities to participate in the innovation process are on offer, even if they are already engaged in one of them (Pohlisch 2019). Pohlisch (2019) concludes that more awareness about the different initiatives could raise positive externalities and create synergies between them.

Building a community in which true collaboration is fostered is critical. The internal crowdsourcing platform should help employees connect and actively share knowledge and ideas instead of only providing solutions to given problems (Malhotra et al. 2017; Simula and Vuori 2012). The network aspect should be much more than just employees being active in generating ideas. The firm should furthermore identify and support experts (e.g., human resources, finance, marketing, etc.) who could support the idea of development process with their knowledge and networks (Smith et al. 2017). This approach can also help integrate internal crowdsourcing into the innovation process and promote its acceptance by the crowd (Zhu et al. 2016).

Managers must have realistic expectations concerning the failure rates of internal crowdsourcing activities (Bailey and Horvitz 2010; Stieger et al. 2012; Pohlisch 2019). They need to be aware of the different paths along with which ideas can create value. Financial returns might be expected to be higher in some business areas than in others. Nevertheless, ideas can also be related to brand image, customer satisfaction, and employee engagement (Benbya and Leidner 2018). Often enough, internal crowdsourcing is not primarily undertaken to generate innovations and revenue streams or to reduce costs but to increase each employee’s innovation efforts and to create a more entrepreneurial and collaborative culture (Elerud-Tryde and Hooge 2014; Leung et al. 2014). The commitment, attitude, and mentality of those directly responsible must also be considered (Leung et al. 2014). Managers who can decide on budgets and activities within the research and innovation departments can be named as key stakeholders here (Benbya and Leidner 2018; Zhu et al. 2016). Their buy-in across the organization was found to be critical for success (Benbya and Leidner 2018; Leung et al. 2014; Zhu et al. 2016). These direct supervisors are often more reluctant to accept the additional task of crowdsourcing (Leung et al. 2014) as they fear it might keep their staff from working on their regular jobs (Knop and Blohm 2018).

From the employee’s point of view, it is particularly important that existing work obligations are recognized and taken into account (Wagenknecht et al. 2017). Building on this, internal crowdsourcing must not be created as an additional task (Prpić et al. 2015). Benbya and Leidner (2018) report that weekly idea meetings can help incorporate internal crowdsourcing into the work routine, therefore making it feel more like part of the regular day job. What is more, the platform needs to be seamlessly integrated into the workflow of employees and easily accessible from everywhere at all times in order to mitigate entry barriers (Rohrbeck et al. 2015). The time invested by employees must be seen as time well spent and not as a waste of resources (Leung et al. 2014; Elerud-Tryde and Hooge 2014; Knop and Blohm 2018; Majchrzak et al. 2009; Pohlisch 2019), and innovation activities must be legitimized (Elerud-Tryde and Hooge 2014; Pohlisch 2019). However, too many tasks and the associated excessive demands can cause the creativity and innovativeness of employees to drop (Arena et al. 2017).

Notwithstanding this, it should be clear that specific time resources need to be allocated towards innovative activities in general and work on the crowdsourcing platform specifically (Malhotra et al. 2017; Simula and Vuori 2012; Wendelken et al. 2014). Stieger et al. (2012) argue that the amount of time allocated should be communicated unambiguously by management in order to prevent employees who participate heavily from being wrongly accused of not working to capacity. This also helps employees assess the amount of time they have to commit (Wendelken et al. 2014). The cultivation of relationships with one’s employees must have a high priority and be planned for the long term, as the crowd is much more static than in external crowdsourcing (Prpić et al. 2015). To increase the number of ideas generated, participants should also be encouraged to freely explore ideas without restrictions, like risk management and cost considerations (Elerud-Tryde and Hooge 2014). The focus should be not so much on monitoring and controlling employees as on creating confidence that time and manpower will be used by employees in a meaningful way (Majchrzak et al. 2009). Management should rely on openness, transparency, and social control mechanisms (Zuchowski et al. 2016).

3.2 Incentive Design

In the academic debate concerning the correct design of the incentive structures of IC, no uniform opinion has emerged so far. However, a strategic examination of the topic is of immense importance in order to ensure a high level of crowd participation. In some of the articles examined, it is assumed that a specific incentive structure is not necessary, as participation should be sufficiently reflected by salaries and bonus payments (Lopez et al. 2010; Skopik et al. 2012). However, most studies advocate specific incentive structures to ensure long-term employee commitment. If an organization decides in favour of concrete incentive structures, material and immaterial incentives are generally possible.

Material incentives include monetary remuneration or non-cash prizes like gift cards and vouchers (Benbya and van Alstyne 2011; Dimitrova and Scarso 2017; Malhotra et al. 2017; Stieger et al. 2012). One possibility to incorporate this would be to introduce a new measurement of innovation performance into the employee appraisal process that takes crowdsourcing activities into account (Benbya and Leidner 2018). In addition to cash prizes for solving a challenge, money could also be awarded to idea owners in order to further develop ideas (Majchrzak et al. 2009), combining material incentives with the intangible incentive of receiving an opportunity to implement one’s idea.

Intangible incentives include, for example, recognition by colleagues (Muhdi and Boutellier 2011; Simula and Vuori 2012; Dimitrova and Scarso 2017; Knop and Blohm 2018; Leung et al. 2014; Scupola and Nicolajsen 2014; Zhu et al. 2016), fun and games (Muhdi and Boutellier 2011; Leung et al. 2014), learning entrepreneurial skills (Dos Santos and Spann 2011; Leung et al. 2014), learning and discovering new things (Muhdi and Boutellier 2011), doing something with purpose (Knop and Blohm 2018), building networks within the organization (Dahl et al. 2011), creating visibility for own ideas (Muhdi and Boutellier 2011; Bailey and Horvitz 2010), and seeing them implemented (Bailey and Horvitz 2010) or employees implementing them themselves (Leung et al. 2014; Malhotra et al. 2017; Zhu et al. 2016). In addition, the commitment of top management is cited as an incentive to participate (Leung et al. 2014). Analysing an internal crowdsourcing community, Muhdi and Boutellier (2011) show that participants value education, broaden their horizons, find like-minded peers, and link for collaboration as most important. Rando et al. (2011) find that helping others, collaboration, problem-solving, curiosity, and dealing with something outside of daily routines were significant motivating factors. Muller et al. (2013) note the ability to make changes in the immediate work environment as a critical motivational factor. In line with the above-mentioned motivational aspects, Scupola and Nicolajsen (2014) find that intangible incentives were more important than material ones. An important aspect reported by Wendelken et al. (2014) is that altruism was not observed to bring a motivational factor in internal innovation communities, although it is an essential aspect of their external counterparts.

However, companies should not rely exclusively on material or immaterial incentives when designing their incentive structures, but rather combine both to optimally promote employee motivation (Benbya and van Alstyne 2011; Smith et al. 2017). Wendelken et al. (2014) find that refraining from monetary rewards will result in a crowd that is smaller, yet more interested in the specific topic and with high intrinsic motivation while turning to monetary rewards tends to increase community size. The incentives should also be tailored to the crowd within the company, since motivational structures can also differ between individual departments of a company (Benbya and Leidner 2018). Taking this idea a step further, Davis et al. (2015) report that, at NASA, employees were asked to submit and vote on ideas on how to remunerate participants. Hence, NASA basically crowdsourced the design of the incentive system to its employees.

Benbya and van Alstyne (2011) recommend using absolute rather than relative incentives to encourage information sharing among employees and to promote an open corporate culture. The idea is that, in this way, not only the relative position in a ranking is relevant for the reward. Instead, all submissions that meet a certain quality standard are rewarded. Relative rewards, however, should be preferred when solutions are substitutes and need to be solved quickly. Furthermore, Benbya and van Alstyne (2011) advocate using variable rewards—for example, by introducing virtual currencies. The underlying problem is that fixed rewards lead to an over- or undersupply of ideas if the reward level is not chosen perfectly. If the reward is too low, ideas with a higher value or ideas that require significant effort will not be submitted. On the other hand, if the reward is too high, employees neglect other important tasks, and there is an oversupply of ideas. Blohm et al. 2010 propose reward team performance instead of individual performance in order to encourage collaboration within and competition between teams. If, however, not individual but collective performance is rewarded, this can lead to a free-riding mentality. Stieger et al. (2012) therefore recommend awarding rewards on an individual basis.

Perhaps one of the strongest motivations for employees to contribute to internal crowdsourcing initiatives is to create ownership in their ideas. As the employee is more strongly linked to the outcome of the initiative (positive and negative), this might increase commitment, which can in turn increase self-satisfaction and a higher identification with the company’s goals (Pohlisch 2019).

In addition to rewards for selected and particularly good ideas, incentive structures should also provide rewards for unfinished ideas to motivate and address as many employees as possible (Malhotra et al. 2017). Ideas from all submitters should always be appreciated in order to signalize to employees that their submissions have value for the company, even if they are not ultimately selected or implemented (Boudreau et al. 2011). To create incentives to comment on other employees’ ideas, Benbya and van Alstyne (2011) and Malhotra et al. (2017) also propose rewarding helpful comments, as well as flagging obsolete and organizing dispersed content. In line with these findings, Scupola and Nicolajsen (2014) find that rewarding these different roles—instead of just the idea contributor—can help to raise awareness of the miscellaneous efforts necessary for a successful internal crowdsourcing process. Pohlisch (2019) finds that giving campaigns a less competitive character and incorporating commenting into the incentive structure could foster the collaborative development of ideas.

One way to present awards could be an event that takes place at a prestigious location. The tremendous visibility of such an event can amplify the incentives provided and deliver significant social recognition (Benbya and Leidner 2018; Smith et al. 2017). Next to physical events, success stories can also be published in the intranet or on a company blog to increase social recognition (Rando et al. 2011).

3.3 Task Definition and Decomposition

The definition, modularization, and distribution of tasks are an integral part of the management of internal crowdsourcing activities and have a significant influence on their success probability (Blohm et al. 2017; Zogaj et al. 2015; Stocker et al. 2012; Simula and Vuori 2012). Defining tasks in a way that they can be solved by individual participants is of great importance to ensure that the solutions can be reintegrated later into complex structures (Zuchowski et al. 2016). More significant tasks need to be processed and edited in such a way that single employees in the crowd can complete them (Knop and Blohm 2018). To increase the likelihood of the emergence of excellent ideas, Benbya and Leidner (2018) recommend formulating problems that address a business need in a very specific and targeted manner. Summarizing, they find that ‘the best approach is to define the scope, provide context, identify constraints and clear goals, and remove as many assumptions as possible’ (Benbya and Leidner 2018, p. 148). Smith et al. (2017) describe the same phenomenon by stating that the problem may potentially be formulated either too broadly or too narrowly. If too broad, the ideas might not be relevant, while the other extreme might hamper more radical ideas. In line with Benbya and Leidner (2018), they argue that ideas should align with the strategic goals of the company. As one potential solution, they propose that challenges can be tied to certain business units. Malhotra et al. (2017) follow this line of argument, stating that how the questions is framed is crucial and influences the employees’ decision whether to participate in internal crowdsourcing or not.

Furthermore, internal crowdsourcing should be used for problems that impact the company in the long-term and not for short-term improvements (Malhotra et al. 2017). In contrast, Riemer et al. (2012b) report that internal crowdsourcing could also be used as a form of ad hoc idea-generation tool comparable to an online brainstorming session, in which an employee starts a conversation with the aim of sourcing spontaneous ideas. However, all things aside, providing assistance to the problem owner so that the particular internal crowdsourcing can be adequately formulated seems of vital importance (Benbya and Leidner 2018; Rando et al. 2011).

Davis et al. (2015) point out another crucial aspect, namely, the knowledge of employees about when to use which open innovation tool for what kind of problem. The idea is that employees need to be educated with respect to the possibilities but also potential problems and pitfalls of internal crowdsourcing so that they are able to use the tool for adequate problems. Hence, in their study Davis et al. (2015) describe how a knowledge management and decision analysis tool was implemented at NASA to help employees decide which of the various innovative tools at hand would be appropriate for their problem.

One last aspect is referring to how time management in setting up a crowdsourcing campaign is related to the specificity of the task. Zhu et al. (2016) propose allocating more time to highly specific tasks, so that participants can develop highly sophisticated solutions, while less time should be allocated to less specific tasks, in order to spur participants to come up with more creative and spontaneous ideas.

3.4 Quality Assurance

Quality assurance within internal crowdsourcing refers to all activities related to ensuring the quality of submissions and final results (Zuchowski et al. 2016). Besides defining tasks, quality assurance has the most significant influence on the success of crowdsourcing campaigns (Zogaj et al. 2015). Ensuring high-quality results is essential to increase the usefulness and credibility of IC campaigns and to avoid employees associating crowdsourcing with low-quality results (Bailey and Horvitz 2010). Crowdsourcing campaigns often generate a plethora of ideas—not all of them are useful. Hence, quality assurance is crucial for the success of crowdsourcing campaigns (Erickson 2012; Pedersen et al. 2013; Vukovic and Naik 2011).

The ideas can be evaluated either by the crowd itself (Bailey and Horvitz 2010; Leimeister et al. 2009; Vukovic and Naik 2011) or with criteria defined a priori (Benbya and Leidner 2018).

The so-called crowdvoting is generally used to generate an initial evaluation of the ideas, while expert evaluation usually takes place according to defined criteria before solutions are actually implemented (Bailey and Horvitz 2010; Benbya and Leidner 2018). Stephens et al. (2016) have shown that crowdvoting is well suited to selecting ideas from a large mass of ideas. At the same time, however, they point out that there is a high degree of centrality with regard to participants and ideas, i.e., a small number of employees are responsible for a large proportion of the activity, which in turn concentrates on a small number of ideas. Thus, popular ideas are usually upvoted more strongly, resulting in a Matthew effect. They have also found evidence of a shared affiliation effect, meaning that employees tend to upvote ideas of their direct peers more often. To solve these problems, they advocate pushing the visibility of less endorsed ideas as well as ideas from outside the employees’ cluster of peers. The results of the work done by Bailey and Horvitz (2010) confirm this and show that the outcome of crowdvotings can reflect the status and network of an employee instead of the quality of the idea. However, they also acknowledge the importance of voting and commenting as a source of input for the author in further developing an idea. To suppress the tendency of users to vote for popular, well-marketed ideas, they recommend letting employees vote on relevant business dimensions instead of merely ‘liking’ ideas. Next to merely voting and rating, the amount of comments on an idea and how in-depth they are can be a significant predictor of idea quality as shown by Elerud-Tryde and Hooge (2014). Comments by peers also help increase the quality of submissions by filtering requests that have no added value to the company (Majchrzak et al. 2009). However, even the amount of comments and votes together might not be a good measure of the impact of a submission. Stieger et al. (2012) find that the higher the entry barrier to engaging meaningfully in a discussion, e.g., because highly specific knowledge is required, the lower the participation rates. However, this might bear no correlation at all to the potential of individual submissions. As an alternative to voting mechanisms, Scupola and Nicolajsen (2014) propose trading fictitious shares of an idea among employees. Muller et al. (2013) reported about one case at an IBM Research organization where every employee was given $100 to invest in idea proposals.

Ransbotham and Westerman (2016) state in their study that internal crowd valuations are distorted by popularity and social aspects and expert valuations are often more closely aligned with the company’s objectives. Correspondingly, Bjelland and Wood (2008) found high-level analysts and managers to be best at selecting the most promising ideas. Leung et al. (2014) report that safe environments for employees can be created if companies rely solely on internal experts in the early stages of the selection process. Further incorporating external experts later on can add a valuable market perspective to the evaluation process. Experts often rank ideas on several different dimensions like innovativeness, feasibility, market potential, and team composition. In a study on internal crowdsourcing processes at SAP, Pohlisch (2019) found that employees sometimes tend to vote strategically and might not possess the often very specific knowledge to adequately evaluate ideas. One massive problem with regard to evaluations by a selected group of experts is that such experts often represent a rare resource and are thus relatively expensive. In addition, identifying experts is a complex and time-consuming process (Lüttgens et al. 2014). Another aspect worth mentioning is that participants might consider the expertise of the judging experts as being insufficient to validate their ideas, especially if they consider themselves to be the expert in a particular field (Leung et al. 2014).

In order to avoid a situation where the evaluation process is not accepted, the evaluation process must be as open and transparent as possible (Leung et al. 2014; Simula and Vuori 2012; Malhotra et al. 2017). Ultimately, feedback to the participants in crowdsourcing initiatives should be as direct as possible. Zhu et al. (2019) were able to show that feedback in internal idea competitions leads to a significantly higher quality of ideas. Furthermore, the feedback should be detailed and should contain constructive proposals on how to improve the ideas, especially if ideas are rejected (Leung et al. 2014; Malhotra et al. 2017). While feedback is normally provided by problem owners and management, the platform should allow for all employees to provide feedback on ideas, possibly leading to a coevolution of ideas (Malhotra et al. 2017). Another approach would be to let senior executives write responses to the most important contributions (Stieger et al. 2012).

To ensure long-lasting participation as well as the best use of the provided solutions, it is vital to integrate the internal crowdsourcing process into a company’s commercialization infrastructure (Leung et al. 2014; Malhotra et al. 2017; Rohrbeck et al. 2015; Pohlisch 2019). This means that there should be a dedicated follow-up process in place for winning as well as for losing ideas. Alternative avenues towards pursuing an idea that was not selected as well as a clear commercialization path for selected ideas should be provided (Leung et al. 2014). Smith et al. (2017) describe one such process at EMC, where a stage-gate process was introduced to ensure that ideas are moved efficiently from concept to implementation. This way, the success rate of ideas could be substantially increased and the process times decreased. Solutions that are not selected should be allowed to be resubmitted at a later stage (Malhotra et al. 2017) and screened for potential other avenues of development (Smith et al. 2017).

3.5 Crowd Selection

With community management, Zuchowski et al. (2016) introduce another component of their governance framework but mainly describe aspects related to selecting the appropriate crowd. Since community management can be understood as a more comprehensive term (Young 2013), this aspect is going to be named ‘crowd selection’. Furthermore, there is a differentiation between the community, which is defined as the entirety of the employees of the company, and the crowd, which refers to the fraction of employees who eventually engage in the internal crowdsourcing activities (Ulbrich and Wedel, see chapter ‘Systematization Approach for the Development and Description of an Internal Crowdsourcing System’ of this book).

Crowd selection is about defining the openness of IC. Usually, IC should be entirely open to all employees of the company. Opening up the process increases the number and diversity of participants and therefore serendipity (Leung et al. 2014; Stieger et al. 2012; Zhu et al. 2016, 2019). What is more, the openness of the platform sends a signal that the contributions of all employees—regardless of hierarchies and organizational affiliation—are welcome, which in turn can lead to increased motivation among participants (Muhdi and Boutellier 2011; Scupola and Nicolajsen 2014; Elerud-Tryde and Hooge 2014). Diversity in the participants leads to a greater variety of solutions, which in turn potentially leads to creative rebound effects (Elerud-Tryde and Hooge 2014). In fact, Arena et al. (2017, p. 4) observed that the majority of winning projects were actually submitted by employees ‘below the radar or working in remote offices’. Not only ideas created by experts are valuable, and smaller, fuzzy ideas often turn out to be very valuable as well (Scupola and Nicolajsen 2014).

Furthermore, Bailey and Horvitz (2010) report that the primary motivation for creating an internal crowdsourcing system at Microsoft was to develop a channel for ideas that were not related to employees’ daily work routines. In line with the previous findings, Muller et al. (2013) do not find significantly different participation rates between managers and non-managers or between different hierarchical levels. Also, the very nature of the idea challenges makes internal crowdsourcing and, along with it, innovation as a normal activity much more present for all employees (Elerud-Tryde and Hooge 2014). In this way, internal crowdsourcing can be seen as creating more equality and opening up the innovation process to all employees regardless of their hierarchical position, area of expertise, or organizational affiliation, potentially leading to a sense of empowerment among employees (Scupola and Nicolajsen 2014).

One problem in opening up the crowdsourcing innovation process to all employees within a company is that not all employees might have access to computers. One way to solve this problem could be to set up terminals in production environments that employees can use to post their ideas, although this entry barrier also poses a hurdle most employees are not willing to take on (Stieger et al. 2012). Allowing employees to submit ideas in the name of colleagues while giving credit to the original idea owner could be another way (Dimitrova and Scarso 2017). Aside from purely access issues, differences in IT competences between employees can introduce biassed participation. To address this, the company could provide ‘a training process to lift the IT and workflow competences of employees in the crowd to a minimum level’ (Knop and Blohm 2018, p. 11).

On the other hand, it is possible to restrict the crowd to a selected circle of employees. Selection is usually based on specific skills and knowledge or context-based criteria, such as membership in a particular organizational unit (Geiger et al. 2011; Simula and Vuori 2012; Knop et al. 2017). Although this reduces the level of diversity among participants, it can lead to a higher degree of professionalism in the contributions (Simula and Ahola 2014). Benbya and Leidner (2018) argue that it is necessary to select participants depending on the properties of the specific task at hand. Experts should be favoured for specialized problems, while less specialized problems benefit from access to miscellaneous knowledge normally distributed throughout the company. Zhu et al. (2016), instead, base their argument on the distinction between process and product innovation. A specified crowd with specific knowledge is to be favoured when process innovations are pursued, while unspecified crowds with diverse knowledge are better suited for product innovations.

In contrast to the idea of including experts in the crowd, Malhotra et al. (2017) propose limiting the influence of these experts, because other participants might be deterred from submitting their ideas by the fact that experts are part of the crowd. They suggest that experts should be used as moderators and motivators. To further increase the number of participants, early adopters can be used to create a critical mass and encourage other employees to participate (Benbya and Leidner 2018; Simula and Vuori 2012; Stocker et al. 2012). Following the same line of argument, Wendelken et al. (2014) report about the strategy of one German toy manufacturer that took this aspect to the extreme. By specifically deciding not to address R&D employees, design staff, lead users, and others who one would expect to be asked, they purposefully engaged employees who were normally excluded from the innovation process. Rando et al. (2011) distinguish between theoretical and technical challenges. While the former benefit from the broad participation of employees with various backgrounds, the latter often require in-depth domain knowledge by experts. While preselecting the crowd might be beneficial in some cases, addressing only R&D employees, for example, might lead to a decrease in the participation of other employees (Riemer et al. 2012b), which in turn could potentially lead to a significant loss in serendipity, negatively influencing the diversity and even radicalness of outcomes.

3.6 Regulations and Legal Implications

An analysis of the literature reveals that this part of managing internal crowdsourcing is heavily under-researched. Only seven of the identified studies mention relevant aspects of this topic at all, and only four of those contribute to the discussion to a significant extent. Their findings can be summarized by three key elements: (1) transparency, (2) anonymity, and (3) protection of information.

First, transparency in this context means that the conditions of participation are clear and that the internal crowdsourcing process is presented as clearly and transparently as possible—from the launch to the process to select a solution (Benbya and Leidner 2018; Pohlisch 2019). Not only being transparent about the design but also allowing participants to ask for changes or additional features could make the system more attractive to employees (Benbya and van Alstyne 2011). Complete transparency concerning the crowdsourcing process can also help reduce objections about any ‘potential exploitation of employees as well as a deterioration in working conditions’ (Knop and Blohm 2018, p. 11) that the works council might have and which in turn could impede the introduction of such a tool within the company (Rohrbeck et al. 2015; Knop and Blohm 2018). Furthermore, barrier-free access needs to be established so that disabled employees (Rohrbeck et al. 2015), employees who do not have access to computers during their daily work routines (Dimitrova and Scarso 2017), or employees who are not physically present on the company site, like salespeople, are not excluded (Stieger et al. 2012). Personal information collected about employees needs to be regulated (Rohrbeck et al. 2015) and should be transparent as well.

Second, anonymity or the option for employees to anonymously participate in the crowdsourcing process is advised repeatedly (Benbya and van Alstyne 2011; Malhotra et al. 2017; Stieger et al. 2012). The idea is that employees might be afraid to admit what they do not know and that protected spaces or the option of anonymity could allow for an environment where controversial information is shared much more readily and freely (Benbya and van Alstyne 2011). Another aspect of this is the fact that anonymity can free employees from their organizational role, hierarchical position, or departmental affiliation, allowing them to more freely share and advocate ideas (Malhotra et al. 2017). However, it is worth mentioning that anonymity within such systems is technically impossible, as postings can always be traced back to their author. The fear that management could theoretically be tracing posts might once again potentially lead to controversial thoughts not being published (Stieger et al. 2012). Stieger et al. (2012) also point out that anonymity would reduce anxiety and apprehensions that could result from being evaluated by peers within the company.

The last aspect mentioned in the reviewed papers is the protection of information. Benbya and van Alstyne (2011) specifically warn about the ‘risk of competitive disclosure’. However, it is generally assumed that intellectual property issues hardly play any role at all in internal crowdsourcing, because all participants from the crowd are contractually bound to the company (Simula and Vuori 2012) and this employment contract usually takes property rights into account (Vukovic and Bartolini 2010). Furthermore, confidentiality agreements or general laws on employee inventions often apply (Zhu et al. 2016). In Germany, for example, the Act on Employee Inventions applies, under which the employee is entitled to remuneration, but the ownership rights to the invention are transferred to the employer if the invention has been developed as part of an employee’s official work duties (Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz 2009). Internal crowdsourcing is thus a way of accessing the distributed knowledge of the crowd without risking the same problems concerning intellectual property rights that could occur in external crowdsourcing (Villarroel and Reis 2010).

4 Conclusion

The purpose of this literature review is to summarize the empirical literature on the management of internal crowdsourcing. The findings presented provide a well-structured source of information that can be used by companies to design their internal crowdsourcing implementations. This might allow them to access the innovation potential of their employees, thereby creating a valuable competitive advantage.

The review above shows that certain aspects of the management of internal crowdsourcing are better understood and much more researched than others. While most studies covered aspects of corporate culture and incentive design, only a few studies contributed to an understanding of task definition and decomposition or regulations and legal considerations. Hence, these two management tasks represent a promising avenue for future research. The works council aspect in particular seems to have been somewhat neglected in the literature. This is astounding, considering that the works council has a right of co-determination for tools like internal crowdsourcing—at least in Germany. Furthermore, endorsement by the works council for the implementation of such tools will most likely increase participation and acceptance among employees.

However, this does not necessarily mean that areas that are more researched are far better understood. As it becomes evident when looking at incentive structures, more work is required concerning the impact of contextual factors (e.g., industry, the goal of crowdsourcing, hierarchy structures, etc.) on the motivations of employees. It is also worth noting that most studies in the analysed sample discuss internal crowdsourcing implementations at large multinational corporations within complex industries, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Hence, future research should also consider investigating the potential of internal crowdsourcing for low-technology industries and small- and medium-sized enterprises.

References

Abu El-Ella N, Stoetzel M, Bessant J, Pinkwart A (2013) Accelerating high involvement: The role of new technologies in enabling employee participation in innovation. Int J Innovat Manag 17(06):1340020

Arena M, Cross R, Sims J, Uhl-Bien M (2017) How to catalyze innovation in your organization. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 58(4):38–48

Bailey BP, Horvitz E (2010) What’s your idea? A case study of a grassroots innovation pipeline within a large software company. In: Proceedings of the 28th international conference on human factors in computing systems, pp 2065–2074

Benbya H, Leidner D (2018) How Allianz UK Used an idea management platform to harness employee innovation. MIS Q Exec 17(2):139–155

Benbya H, van Alstyne MW (2011) How to find answers within your company. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 52(2):65–76

Bjelland O, Wood RC (2008) An inside view of IBM’s ‘innovation jam’. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 50(1):32–40

Blohm I, Bretschneider U, Leimeister JM, Krcmar H (2010) Does collaboration among participants lead to better ideas in IT-based idea competitions? An empirical investigation. In: Proceedings of the 43rd Hawaii international conference on system sciences, Koloa, Kauai, HI, USA, 5–8 January

Blohm I, Zogaj S, Bretschneider U, Leimeister JM (2017) How to manage crowdsourcing platforms effectively? Calif Manag Rev 60(2):122–149

Boudreau KJ, Lacetera N, Lakhani KR (2011) Incentives and problem uncertainty in innovation contests: an empirical analysis. Manag Sci 57(5):843–863

Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz (2009) Gesetz über Arbeitnehmererfindungen: ArbnErfG

Dahl A, Lawrence J, Pierce J (2011) Building an innovation community. Res Technol Manag 54(5):19–27

Davis JR, Richard EE, Keeton KE (2015) Open innovation at NASA: a new business model for advancing human health and performance innovations. Res Technol Manag 58(3):52–58

Denyer D, Parry E, Flowers P (2011) “Social”, “open” and “participative”? Exploring personal experiences and organisational effects of Enterprise2.0 use. Soc Softw Strat Technol Community 44(5):375–396

Dimitrova S, Scarso E (2017) The impact of crowdsourcing on the evolution of knowledge management: Insights from a case study. Knowl Process Manag 24(4):287–295

Dos Santos R, Spann M (2011) Collective entrepreneurship at Qualcomm: combining collective and entrepreneurial practices to turn employee ideas into action. R&D Manag 41(5):443–456

Elerud-Tryde A, Hooge S (2014) Beyond the generation of ideas: virtual idea campaigns to spur creativity and innovation. Creativ Innovat Manag 23(3):290–302

Erickson LB (2012) Leveraging the crowd as a source of innovation: does crowdsourcing represent a new model for product and service innovation? In Proceedings of the 50th annual conference on computers and people research, Milwaukee, WI, USA, May, pp 91–96

Erickson LB, Trauth EM, Petrick I (2012) Getting inside your employees’ heads: Navigating barriers to internal-crowdsourcing for product and service innovation. In ICIS 2012 proceedings

Geiger D, Seedorf S, Schulze T, Nickerson RC, Schader M (2011) Managing the crowd: towards a taxonomy of crowdsourcing processes. In: Proceedings of the seventeenth Americas conference on information systems, Detroit, MI, USA, 4–7 August

Henttonen K, Rissanen T, Eriksson P, Hallikas J (2017) Cultivating the wisdom of personnel through internal crowdsourcing. Int J Innovat Technol Manag (IJITM) 16(2):117–132

Howe J (2006) The rise of crowdsourcing. Wired Mag 14(6):1–4

Knop N, Blohm I (2018) Leveraging the internal work force through crowdtesting: crowdsourcing in banking. In: ICIS 2018 proceedings, San Francisco, USA

Knop N, Durward D, Blohm I (2017) How to design an internal crowdsourcing system. In: ICIS 2017 proceedings

Leimeister JM, Huber M, Bretschneider U, Krcmar H (2009) Leveraging crowdsourcing: activation-supporting components for IT-based ideas competition. J Manag Inform Syst 26(1):197–224

Leung N, van Rooij A, van Deen J (2014) Eureka!: lessons learned from an evaluation of the idea contest at Deltares. Res Technol Manag 57(4):44–50

Lopez M, Vukovic M, Laredo J (2010) PeopleCloud service for enterprise crowdsourcing. In: Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on services computing, Miami, Florida, USA, pp 538–545

Lüttgens D, Pollok P, Antons D, Piller F (2014) Wisdom of the crowd and capabilities of a few: internal success factors of crowdsourcing for innovation. J Bus Econ 84(3):339–374

Majchrzak A, Cherbakov L, Ives B (2009) Harnessing the power of the crowds with corporate social networking tools: how IBM does it. MIS Q Exec 8(2)

Malhotra A, Majchrzak A, Kesebi L, Looram S (2017) Developing innovative solutions through internal crowdsourcing. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 58(4):73–79

Muhdi L, Boutellier R (2011) Motivational factors affecting participation and contribution of members in two different Swiss innovation communities. Int J Innovat Manag 15(03):543–562

Muller M, Geyer W, Soule T, Daniels S, Cheng L-T (2013) Crowdfunding inside the enterprise: employee-initiatives for innovation and collaboration. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, pp 503–512

Ooms W, Bell J, Kok RAW (2015) Use of social media in inbound open innovation: building capabilities for absorptive capacity. Creativ Innovat Manag 24(1):136–150

Pedersen J, Kocsis D, Tripathi A, Tarrell A, Weerakoon A, Tahmasbi N, Xiong J, Deng W, Oh O, de Vreede G-J (2013) Conceptual foundations of crowdsourcing: a review of IS research. In: 46th Hawaii international conference on system sciences (HICSS 2013): Wailea, [Maui], HI, USA, 7–10 Jan 2013

Pohlisch J (2019) Internal crowdsourcing at SAP. In: Proceedings of the 14th European conference on innovation and entrepreneurship (ECIE), Kalamata, Greece, 19–20 September, pp 1201–1209

Prpić J, Shukla PP, Kietzmann JH, McCarthy IP (2015) How to work a crowd: Developing crowd capital through crowdsourcing. Bus Horiz 58(1):77–85

Rando CM, Fogarty JA, Richard EE, Davis JR (2011) Open collaboration: a problem solving strategy that is redefining NASA’s innovative spirit. In: 62nd international astronautical congress

Ransbotham S, Westerman GF (2016) Agency conflict in internal corporate innovation contests

Rao D (2016) Enterprise crowdsourcing to sustain culture of innovation. http://www.cio.in/opinions/enterprise-crowdsourcing-sustain-culture-innovation. Accessed 21 Nov 2018

Riemer K, Overfeld P, Scifleet P, Richter A (2012a) Oh, SNEP! The dynamics of social network emergence—the case of Capgemini Yammer. Business information systems working paper series

Riemer K, Scifleet P, Reddig R (2012b) Powercrowd: enterprise social networking in professional service work: a case study of Yammer at Deloitte Australia. Business information systems working paper series

Riemer K, Stieglitz S, Meske C (2015) From top to bottom—investigating the changing role of hierarchy in enterprise social networks. Bus Inform Syst Eng 57(3):197–212

Rohrbeck R, Thom N, Arnold H (2015) IT tools for foresight: IT tools for foresight: The integrated insight and response system of Deutsche Telekom Innovation Laboratories. Technol Forecast Soc Change 97:115–126

Scupola A, Nicolajsen HW (2014) The impact of enterprise crowdsourcing on company innovation culture: the case of an engineering consultancy. In: Commisso TH, Nørbjerg J, Pries-Heje J (eds) Nordic contributions in IS research. Springer, Cham

Simula H, Ahola T (2014) A network perspective on idea and innovation crowdsourcing in industrial firms. Ind Market Manag 43(3):400–408

Simula H, Vuori M (2012) Benefits and barriers of crowdsourcing in B2B firms: generating ideas with internal and external crowds. Int J Innovat Manag 16(06):1240011

Skopik F, Schall D, Dustdar S (2012) Discovering and managing social compositions in collaborative enterprise crowdsourcing systems. Int J Cooper Inform Syst 21(04):297–341

Smith C, Fixson SK, Paniagua-Ferrari C, Parise S (2017) The evolution of an innovation capability. Res Technol Manag 60(2):26–35

Steinhuser M, Smolnik S, Hoppe U (2011) Towards a measurement model of corporate social software success—evidences from an exploratory multiple case study. In 2011 44th Hawaii international conference on system sciences (HICSS), 4–7 Jan 2011, Koloa, Kauai, HI, pp 1–10

Stephens B, Chen W, Butler JS (2016) Bubbling up the good ideas: a two-mode network analysis of an intra-organizational idea challenge. J Comput Mediated Commun 21(3):210–229

Stieger D, Matzler K, Chatterjee S, Ladstaetter-Fussenegger F (2012) Democratizing strategy: how crowdsourcing can be used for strategy dialogues. Calif Manag Rev 54(4):44–68

Stocker A, Richter A, Hoefler P, Tochtermann K (2012) Exploring appropriation of enterprise wikis. Comput Support Cooper Work (CSCW) 21(2-3):317–356

Surowiecki J (2004) The wisdom of crowds: Why the many are smarter than the few and how collective wisdom shapes business, economies, societies, and nations. Doubleday, New York

Villarroel AJ, Reis F (2010) Intra-corporate crowdsourcing (ICC): leveraging upon rank and site marginality for innovation. In: CrowdConf, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4 October

Vukovic M, Bartolini C (2010) Towards a research agenda for enterprise crowdsourcing. Leveraging applications of formal methods, verification, and validation. In 4th international symposium on leveraging applications, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, 18–21 October. Springer, Berlin pp 425–434

Vukovic M, Naik VK (2011) Managing enterprise IT systems using online communities. In: 2011 IEEE international conference on services computing (SCC), Washington, DC, USA, 4–9 July. IEEE, pp 552–559

Wagenknecht T, Levina O, Weinhardt C (2017) Crowdsourcing in a public organization: transformation and culture. In: AMCIS 2017 proceedings

Webster J, Watson RT (2002) Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: writing a literature review. MIS Q 26(2):xiii–xxiii

Wendelken A, Danzinger F, Rau C, Moeslein KM (2014) Innovation without me: why employees do (not) participate in organizational innovation communities. R&D Manag 44(2):217–236

Young C (2013) Community management that works: how to build and sustain a thriving online health community. J Med Internet Res 15(6):e119

Zhu H, Sick N, Leker J (2016) How to use crowdsourcing for innovation? A comparative case study of internal and external idea sourcing in the chemical industry. In: Proceedings of the IEEE management of engineering and technology (PICMET), Honolulu, HI, USA, 4–8 September, Portland, OR, USA. IEEE, pp 887–901

Zhu H, Kock A, Wentker M, Leker J (2019) How does online interaction affect idea quality? The effect of feedback in firm-internal idea competitions. J Prod Innovat Manag 36(1):24–40

Zogaj S,Bretschneider U (2014) Analyzing governance mechanisms for crowdsourcing information systems: a multiple case analysis. In: ECIS 2014 proceedings

Zogaj S, Leicht N, Blohm I, Bretschneider U (2015) Towards successful crowdsourcing projects: evaluating the implementation of governance mechanisms. In: ICIS 2015 proceedings

Zuchowski O, Posegga O, Schlagwein D, Fischbach K (2016) Internal crowdsourcing: conceptual framework, structured review, and research agenda. J Inform Technol 31(2):166–184

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pohlisch, J. (2021). Managing the Crowd: A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Internal Crowdsourcing. In: Ulbrich, H., Wedel, M., Dienel, HL. (eds) Internal Crowdsourcing in Companies. Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52881-2_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52881-2_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-52880-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-52881-2

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)