Abstract

This article deals with the question of how internal crowdsourcing can be used as a tool to support employee qualification measures and help develop their competencies in organizations. The first chapter examines the current state of the competence research. A paradigm shift from ‘qualification and professional development’ towards ‘competencies’ and the implications for the concept are described. Chapter “An Introduction to Internal Crowdsourcing” deals with the analyses and work on the subject of competence acquisition and development, including considering the results of two interview series and two workshops. In chapter “Managing the Crowd: A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Internal Crowdsourcing”, the authors present a combined and practical approach to support competence development through internal crowdsourcing in organizations. Finally, the last chapter sums up main results and perspectives for competence development through a combination of virtual and face-to-face working processes.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Qualification and competence development

- Professional development

- New learning culture

- Virtual and face-to-face working processes

1 Introduction

The authors of this article try to find answers to the questions concerning how to design an approach for competence development through internal crowdsourcing in order to create value for the employees as well as for the organization as a whole. In order to find these answers, the authors developed an application-oriented concept for qualification, further education, qualification and competence development through the use of internal crowdsourcing as part of the research project ‘Internes Crowdsourcing in Unternehmen—ICU’ (internal crowdsourcing in companies).

The search for a suitable approach and the concept development were mainly based on two sources: Firstly, the current situation in the theoretical and empirical research work on the subject of qualification and competence development was examined, taking into consideration the corresponding preconditions, framework conditions and examples. Secondly, this research was processed together with an empirical part consisting of different collaborative elements that were developed together with the industry partner, the utility company GASAG. These empirical elements included interviews with employees and managers from that company, workshops with their employees and with employees of other companies who are responsible for personnel development and experienced in the topic.

Measures for competence development through internal crowdsourcing do not intend to replace current training measures for employee qualification but are designed to complement them and provide starting points for reviewing the previous qualification efforts and education programmes. The establishment of an internal company network, the transfer of knowledge as well as an exchange between employees from different departments and areas are central elements in the concept which first had to be put in place. The intention was to create an application-oriented concept for qualification, further education, for developing qualification measures and competencies through the use of internal crowdsourcing. By applying the concept, the aim was that employees be given opportunities to discover their individual competencies and interests, to develop them further and to articulate their existing qualifications. Furthermore, the development of digital skills, especially using digital application software, should play a special role in the development of measures and concepts.

Taking into consideration these framework conditions underlying an application-oriented concept for qualification and competence development, three approaches are suggested, each of which involves processing in the digital crowdsourcing application:

-

1.

Crowdvoting for a collaborative assessment and prioritization of competencies

-

2.

A multiple choice test for assessing existing knowledge and expertise as well as knowledge transfer

-

3.

The use of crowdcreation processes for competence development and as a starting point for the promotion of a knowledge transfer and an internal company network

These three approaches, which are further elaborated on in chapter “Managing the Crowd: A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Internal Crowdsourcing” of this article, intend to enable employees as well as the management to develop a self-reflective learning process close to everyday working conditions and tasks. This article describes a possible application of these three approaches, which together form the basis for the application-oriented concept for qualification, further education and competence development through the use of internal crowdsourcing.

2 Paradigm Shift: From ‘Qualification and Professional Development’ Towards ‘Competences’

A paradigm shift has been observed in the last two decades both in the specialist debates in German-speaking countries and in the human resources development departments of many companies. A shift is taking place from the classical forms of employee qualification to a concentration on the competencies of employees—and with it a shift from classical training and further education activities in companies to competence development approaches. The following section describes how the concept of competence is defined, against background of which the focus has shifted from qualification to competence, and how this shift is interpreted and evaluated in the specialist debate—particularly in German-speaking countries—and used in this research project.

The concept of competence has been discussed in detail in specialist literature since the 1990s and has been further differentiated and specified by Erpenbeck, among others. Accordingly, competence generally encompasses all skills, knowledge and approaches that a person has acquired and also applies in the course of his or her life (Erpenbeck and Heyse 1996, pp. 9–13; Baitsch 1996, pp. 102–112).

In a detailed description of the concept of competence and in addition to earlier remarks, competencies are described as ‘self-organization dispositions’ (Erpenbeck and Rosenstiel 2007, p. 489), in contrast to other aspects and constructs such as skills, knowledge or qualifications. While these can be tested directly, competencies can only be developed from the realization of existing and developed dispositions, i.e. only retrospectively from the actions or performance of a person. This applies in particular to creative solutions to nonroutine tasks and new challenges. ‘Competencies can contain experiences, abilities, will components, knowledge and values—but they cannot be reduced to these, but include them in relationships relevant to disposition and action. Competencies are founded by knowledge, constituted by values, disposed as abilities, consolidated by experience, realized on the basis of will. Self-organized ability to act is the goal of every competence development’ (Erpenbeck and Rosenstiel 2007, p. 489, see also Lichtenberger 1999, p. 257). Competencies require different types of knowledge, such as specialist or methodological knowledge. What is decisive, however, is the fact that and how this knowledge is combined with individual experience, skills and behaviour and applied in everyday work.

In its definition of competence, the OECD also emphasizes the interplay of different knowledge stocks, skills, attitudes and behaviours, highlighting communication competence as an example: ‘A competence is more than just knowledge and cognitive abilities. It is about the ability to cope with complex demands by using psychosocial resources […] in a certain context. For example, the ability to communicate is a competence that can be based on a person’s language skills, practical IT skills and attitudes towards the communication partner’ (OECD 2005, p. 6). From a socio-educational perspective, Veith sheds light on the concept of competence and stresses the need for children, young people and adults to acquire ‘intelligent knowledge’ in order to deal with complexity and insecurity in various areas of life. In connection with competencies, it also points to the development of individual strategies for action in order to be able to act autonomously (as a ‘subject’ in the sense of the term) in concrete cases of application. An overview of further definitions and classifications of the concept of competence can be found in Stark (Stark 2009, p. 6).

2.1 The Societal-Cultural Context of Competence

A shift in focus from classical qualification to competence development would seem to make sense taking into consideration the challenges that are emerging within the framework of a complex modern and accelerating working world. The increasing examination of competence in the specialist literature in comparison to qualification also points towards a change of focus from input orientation towards outcome orientation. This lends greater importance to a person’s individual abilities, skills and knowledge than to what has been learned in vocational training or studies (Erpenbeck and Rosenstiel 2007, p. XIV; Münchhausen and Schröder 2009, p. 19). As such, classical training and further education programmes are changing to take on new approaches to individual competence development, which presupposes vocational qualification and the corresponding knowledge as a basis.

Through targeted competence development based on individual learning and development processes and different forms of learning in training and work, competencies are to be developed and deepened. According to Borner, this also requires a new learning culture in which the focus of learning shifts “… away from the teachers to the learners, towards individual learning needs, development biographies and constructions of meaning. New learning culture is […] facilitation-oriented, emancipative-self-organizational and competence-centred and contains and thematizes real social and communicative requirements’” (Borner 2008, p. 6). In a similar way, Sprafke emphasizes the importance of individual employee competencies for the dynamics and adaptability of companies and goes in greater depth into the function of empowerment, i.e. the empowerment of employees to act in a self-determined or self-responsible manner when developing competencies (Sprafke 2016). This also includes designing work processes in such a way that they activate and promote competencies and continuously support independent learning processes. ‘Furthermore, the working environment should be designed in such a way that existing competencies are exploited to the full for the benefit of employees and companies. […] However, individual experiences and interests should be increasingly taken into account in order to make it possible to build on competencies already acquired’ (Richter M et al. 2005, p. 8).

In addition to supporters of concentrating competencies in the learning and working world, however, critical voices can also be heard within the specialist debate, where this development is questioned and regarded as problematic. Bolder and Dobischat, for example, point out that with an increasing concentration on the development of competencies, which takes the place of company and institutionalized qualification and further training measures and should also be as self-organized and self-responsible as possible, responsibility is transferred to the individual, as are the monetary costs and the time required (Bolder and Dobischat 2009, p. 7). Veith warns of a ‘competence trap’, i.e. the danger of burnout and self-exploitation, which can arise from continuous performance optimization and the tireless pursuit of maintaining and improving one’s own competitiveness (Veith 2014, p. 63). Lederer, on the other hand, complains in this context that competence orientation tends to be instrumental and that it is too strongly oriented towards market-economy behaviour (Lederer 2014, p. 263).

Erpenbeck and Sauter also deal with this criticism in detail but come to a completely different conclusion. They take up the debate about the pros and cons of a shift from qualifications to competencies and argue in favour of an even stronger orientation towards competence in order to prevent the ‘disappearance of knowledge’ (Erpenbeck and Sauter 2016, p. 25). The reality has to be acknowledged that companies will increasingly shift their focus to a demand-oriented development of skills, abilities and expertise. This tendency will determine future competence development measures and ‘stock learning’ will be replaced by ‘learning on demand’ (Erpenbeck and Sauter 2016, p. 129). The authors classify the competence society as a ‘social megatrend’ in which competence development is the ‘education of the future’ (Erpenbeck and Sauter 2016, p. 242). Therefore an ‘education revolution’ is to be demanded (Erpenbeck and Sauter 2016, p. 250).

2.2 Capacity Assessment and Competence Development

The concept of competence thus encompasses different abilities, skills, experiences and areas of knowledge as well as their combination in specific contexts and under specific situational conditions and challenges. Due to the complex interplay of different influencing factors, special requirements are associated with both the recording and the development of competencies.

The acquisition of competencies by employees is the necessary basis to render them able to consciously and creatively participate in a company and to be able to further develop in a targeted manner. Accordingly, the demand for concrete methods and measuring procedures—beyond the more traditional procedures for checking knowledge and certifying qualifications—has increased in recent years. The intention behind using such procedures is to identify competencies that are relevant for a company in order to find suitable personnel, deploy them optimally and organize targeted further training measures (Münk and Reglin 2009, p. 7). Against this background of the increasing importance of a ‘learning enterprise’ that continuously adapts to dynamic conditions, the relevance of competence recording and competence development based on it also becomes clear (Richter M et al. 2005, p. 15).

Of fundamental importance for any consideration and application of competence assessment is also the situational relevance of competencies. A specific (work) situation determines both the activation of competencies and their degree of development. This means, on the one hand, that the situation sets the framework for which competencies can be regarded as relevant and which are visible and thus ascertainable. To be able to make reliable and comprehensive statements regarding a person’s competence, the situation must therefore be taken into account in the development and use of competence assessment procedures. It should be described as precisely as possible in order to place the competence recorded in context and assess it accordingly and to serve as a starting point for further competence development (Kaufhold 2006, p. 24). The actions of a person in a certain situation are therefore ideally the category in which competence is recorded. Conversely, a competence assessment must always be viewed in the concrete and realistic context of action (Kaufhold 2006, p. 96). On the other hand, the connection between situation and competence means that a competence assessment is more meaningful in different situations than in only one situation. For the most far-reaching and meaningful possible recording of existing competencies, it is therefore advisable to conduct a survey of these in different situations (Kaufhold 2006, p. 24).

One way of recording competence as a way of capacity assessment in the context of a particular situation is to use case-oriented tests to achieve a realistic representation of a situation, i.e. a direct reference to the situation. Such tests include possible conditions for action, courses of action and actors involved. The application of such procedures can provide insights into a person’s performance, which in turn can be used to draw conclusions about their competencies and their further development (Kaiser 1998, p. 199). In addition to case-oriented tests, surveys can also be used to record or assess competencies as long as the prerequisite for classification in a situational context is fulfilled. Such surveys can be found, for example, in multiple choice tests as part of assessment centres or related assessment procedures (Schuhmacher 2009; Obermann 2018).

In addition to these theoretical assumptions, a number of practical framework conditions must also be taken into account when identifying and developing competencies in a company. In principle, such measures should always be considered in conjunction with the underlying explicit and implicit objectives, the corresponding actors and groups of actors and their interests. This is used to decide which procedure or combination of different procedures is appropriate. The following questions are associated with this: Which general goals are to be achieved with the measurement, i.e. which statement is it trying to make? And: What concrete entrepreneurial goals are associated with competence assessment and development? Individual methods for competence assessment are ‘… depending on the research objectives and purposes as well as the underlying understanding of competence, each of them differently suitable’ (Kaufhold 2006, p. 31). On the basis of a chosen strategy, the objectives are further defined, as well as the period in which a measure is carried out, the method(s) used, the indicators to be collected and the person(s) involved. Further factors for a successful competence assessment include a high degree of “… participation through the involvement of all participants, credibility through inclusion in the overall strategy, transparency through broad information and disclosure of objectives and purposes and the exploitation of results, reliability through compliance with quality criteria in implementation, legitimacy through the exclusion of use for selection, professionalism through appropriate preparation, implementation and follow-up of competence measurement, sustainability through the combination of competence measurement and competence enhancement” (Richter M et al. 2005, p. 14).

2.3 Competence Models, Competence Classes, ‘Action Anchors’ and Measurement Methods

Proceeding from a concept of competence as described above, which is widely accepted in German-speaking companies, i.e. the concept of competence as the ability to self-organize and creatively act in new tasks and challenges, the competence models are also based on the principle of self-organization and on the ability to ‘… act in a self-organized manner in open, complex and dynamic situations’ (Sauter and Staudt 2016b, p. 14).

The main competence areas provide a starting point from which competencies can be categorized in a competence model—thus providing an estimation of what competencies exist. Some of these are also referred to in the literature as ‘partial competencies’ (Bunk 1994), ‘basic types of competence’ (Richter M et al. 2005), ‘basic dimensions of competence’ (Sauter and Staudt 2016b), ‘basic competencies’ (Erpenbeck and Sauter 2016), ‘competence classes’ or ‘key competencies’ (both Erpenbeck and Rosenstiel 2007).

We will continue to use the term ‘competence classes’ and initially orient ourselves towards the classification logic of Erpenbeck and Rosenstiel, which is widely recognized in the literature:

-

1.

Personal competencies: The dispositions of a person to act in a reflexive, self-organized manner, i.e. to assess themselves, to develop productive attitudes, values, motives and self-images, to develop their own talents, motivations, performance and proposals and to develop and learn creatively within the framework of work and outside.

-

2.

Activity- and implementation-oriented competencies: The disposition of a person to act actively and holistically in an organized manner and to direct this action towards the implementation of intentions, projects and plans—either for oneself or also for others and with others, in a team, in the company and in the organization. These dispositions thus include the ability to integrate one’s own emotions, motivations, abilities and experiences and all other competences—personal, technical-methodical and social-communicative—into one’s own desire to perform and to successfully implement actions.

-

3.

Technical-methodical competencies: The disposition of a person to act in a self-organized manner, both mentally and physically, when solving objective problems, i.e. to solve problems creatively with technical and instrumental knowledge, skills and abilities, to classify and to evaluate knowledge in a meaningful way; this includes the disposition to organize activities, tasks and solutions in a methodically self-organized manner and to develop the methods creatively.

-

4.

Social-communicative competencies: The dispositions to act in a communicative and cooperative way, i.e. to engage creatively with others, to build relationships, to behave in a group and relationship-oriented way and to develop new plans, tasks and goals.

These four competence classes are used in many companies as a basis for competence models, which in turn can be used for competence assessment. As a rule, they are supplemented by additional information such as fields of competence (e.g. ‘leadership competence’), the competencies themselves (e.g. ‘delegation ability’) and so-called anchors for action (e.g. ‘delegation of demanding tasks and competencies’) and thus further concretized. Sauter and Staudt propose a description of the individual competencies with up to six action anchors, as well as an expression of the individual competencies on a scale from ‘hardly available’ to ‘extraordinarily strong’ (partly also ‘abundantly available’) (Sauter and Staudt 2016b, p. 16).

The approach of the action anchors has a kind of ‘bridge function’ both in the development of competence models and in the recording or assessment of competencies. The term ‘action anchor’ (e.g. Erpenbeck and Sauter 2016, p. 23) refers to concrete actions or behaviours through which competencies can be made visible and finally ascertainable. They thus represent a formulation of competencies as behaviours. This principle is also used in the evaluation of answers and solutions within the framework of assessment centres. There, this formulation of competencies is partly called ‘behavioural anchor’ but pursues the same goal (Obermann 2018, p. 95; Schuhmacher 2009, p. 76). Conversely, action and behaviour anchors also offer good starting points for formulating questions on competence recording in advance in such a way that plausible and comprehensible conclusions can be drawn about competencies (Fig. 1).

Competence model with operationalization example (modified from Sauter and Staudt 2016b)

There are many different approaches and procedures for competence assessment that are used in practice. There is no such thing as a ‘standard procedure’ as there is no such thing as the ‘best’ procedure. Rather, the choice of a certain procedure depends on the objective pursued with the competence recording, the company’s orientation and the job profiles of the employees (Richter M et al. 2005, p. 8). As a rule, competence assessment procedures are derived from different aptitude diagnosis procedures or form a hybrid of these. These include biographical methods, activity analysis, interviews, personality procedures, assessment centre procedures, self-description and external description (or combinations of these two approaches), work samples, case studies, test procedures or simulations and scenarios (Sauter and Staudt 2016a, p. 7). In addition to complex and time-consuming methods for recording competencies, there are also simple methods that are specially designed for high user-friendliness. The latter include, for example, multiple choice surveys, which are similar to an assessment centre procedure and are aimed both at the pure query of knowledge and at the acquisition of specialist and methodological competencies.

2.4 Competence Development and a New Learning Culture

In this study, the term ‘competence development’ is used synonymously with the terms ‘competence promotion’ or ‘competence extension’. It thus refers to the development or expansion of competencies among the employees of a company. These are competencies which are classified by the management as decisive against the background of the strategic orientation of the company, as well as those which are regarded by the employees as particularly relevant for their own work.

A concept for qualification and further training through internal crowdsourcing with a focus on competence development can include classic elements of knowledge transfer (such as training courses, seminars or workshops) but should go much further. Internal crowdsourcing—and specifically the crowdsourcing application software—should represent a platform to enable, promote and consolidate competence development as a process. In this way, internal crowdsourcing can ideally function as a vehicle for a ‘new learning culture’: ‘The new learning culture attaches great importance to informal learning outside of continuing educational institutions and specified certifications and makes it possible in a systematic manner. It assumes the dominant role of self-organized learning over forms of externally controlled or externally organized learning. […] The new learning culture is thus oriented towards enabling, self-organising and is competence-centred. It is thus directed towards comprehensive competence development—comprehensive competence development requires the new learning culture; both are inseparable’ (Erpenbeck and Rosenstiel 2007, p. XX).

Open learning environments are a promising way of developing competencies in the light of a new learning culture of this kind. These are generally provided via online platforms, the core function of which is to enable employees to exchange experience and solutions to problems with one another. The aim is to create internal company networks (Barth 2008, p. 204; Erpenbeck and Sauter 2016, p. 130; Sauter and Staudt 2016b, p. 37). This is not primarily about exchanging documents and teaching materials but about the solution-oriented activities of employees and employee interaction. Thus, the open learning environment is ‘… a social competence community, in which learners work together on problems from their practical work as well as in practical projects and at the same time build up their competencies, actively exchange information on topics, leave comments or evaluate contributions from their learning partners’ (Sauter and Staudt 2016b, p. 39). It should be mentioned here that the use of such online platforms can also lead to communication and cooperation across departmental boundaries within companies.

Barth outlines the following features as prerequisites for successful competence development in open learning environments (Barth 2008, p. 205):

-

1.

An understanding of learning as an open-ended and self-organized search process, which strengthens the individual’s initiative and responsibility

-

2.

An ability to solve problems based on participation, empathy and collaboration

-

3.

Dealing with complex and authentic problems from different perspectives

Since employees in most companies are more accustomed to classical learning and further training formats, Erpenbeck and Sauter propose that self-organized forms of learning be introduced gradually. In this way, employees are given the opportunity to gradually get used to this new form of collaborative learning (Erpenbeck and Sauter 2016, p. 130). For example, along the lines of a blended learning concept, a didactically meaningful combination of conventional face-to-face courses and new e-learning formats can take place, in which the staff members drive forward their further training on their own initiative and responsibility, but this is embedded in a framework of given contents and binding learning objectives and possibly accompanied by tutors. Beyond such knowledge transfer, in a further step, competence development could take place within the framework of a social blended learning arrangement in which the employees work collaboratively within an open learning environment on a real or realistic case study. This also seems very advisable or necessary in order to involve employees who are not very technically proficient and to be able to support them in their competence development.

3 Analyses and Work on the Subject of Competence Acquisition and Development

By examining the usability of intranet approachesFootnote 1 to improve innovation processes and to develop competencies, the ICU Project is breaking new ground. In addition to the elaboration and derivation of theoretical and conceptual foundations, it was essential to obtain concrete and authentic experiences and assessments on this topic directly from the company of the industry partner. Therefore, several guideline-supported interviews with a coordinated selection of high-level personnel as well as co-workers were accomplished. This is described below.

3.1 Interviews: Perspectives for GASAG Executives

As part of the ICU Project, five guideline interviews were conducted in September 2017 with members of GASAG’s senior management. The aim of these interviews was to find out more about the attitudes and perspectives of the interviewees on the topics of qualification, further training and competencies. People from several different divisions of management were interviewed.

The survey was conducted using a structured interview guideline, with the questions being clustered into two areas: on the one hand, questions were asked about previous measures in the company, as well as about personal experiences and the corresponding assessments of these measures. On the other hand, questions tended to be asked about the future, relating to understanding, expectations and possible goals associated with qualification and competence expansion within the framework of ICU.

3.2 Summary of the Core Statements

From the interview results, the following core statements can be made about the needs and expectations for successful qualification, further training and competence expansion:

-

The measures for imparting specialist knowledge should be improved.

-

A common and interdisciplinary search for solutions to problems and a shared accomplishment of tasks should be promoted.

-

More flexible forms of cooperation within the company should be developed and implemented.

-

It would be desirable to create an overview of the competencies available in the company.

-

Digital and entrepreneurial competencies should be strengthened.

-

A networking of employees with multipliers from different areas of the company is to be aimed at.

-

A more open corporate culture, more flexible work organization and more employee participation are desired in order to facilitate competence development.

-

Possible worries by employees about there being increased employee control should be taken seriously and allayed.

The answers from the interviews were taken into consideration when developing the application-oriented concept for qualification and competence development. Some of the core statements (e.g. the implementation of more flexible forms of cooperation, the desire for an internal employee network or the desire to strengthen digital and entrepreneurial competencies) were directly implemented into the development of the third approach ‘crowdsolving/crowdcreation’ (see section “Synthesis of the Literature”).

3.3 Interviews: Perspectives of GASAG Employees

Interviews were conducted with employees of GASAG Group companies. These were six interviews with people from different divisions of the company.

Just like the interviews with members of GASAG’s management, the employee interviews were also conducted with the aim of finding out more about the perspectives of the discussion partners on the topics of qualification, further training and competencies. As before, this survey was conducted according to a structured interview guideline, whereby the questions were clustered into three areas: questions about experiences with qualification and further training (reference to the past), questions about the perception and understanding of competencies, as well as questions about needs, ideas and expectations regarding qualification, further training and competence expansion within the framework of the ICU Project (reference to the future).

3.4 Summary of the Core Statements

From the interview results, the following core statements were identified, which express the needs and expectations of a successful qualification, further training and competence extension:

-

Qualification and further training measures should be geared closely to the working reality of the employees and contain practical tasks.

-

An exchange among employees should be encouraged, and an internal company network should be established to facilitate knowledge transfer.

-

Employees should be able to contribute their own questions, interests and ideas.

-

Competencies such as teamwork, independence, flexibility, openness and the ability to change perspectives are seen as particularly important for future work.

-

The way digital application programs are handled should be improved.

-

Certificates can be a useful incentive to participate in qualification measures.

-

It would be interesting to have a cross-functional combination of employees in the sense of competence-based teams for special topics.

-

There could be ‘mentors’ for different topics who could help with the realization of projects.

Like the answers from the previous interviews with GASAG executives, the perspectives of the employees were taken into consideration when developing the approaches for the application-oriented concept for qualification and competence management. This is particularly reflected in the third approach ‘crowdsolving/crowdcreation’ (see section “Synthesis of the Literature”), where answers are given to some of the employees’ needs and wishes (e.g. fostering exchange among employees, building of competence-based teams for special topics based on a cross-functional combination of employees or a more direct combination of qualification and further training measures based on the employee’s working reality).

3.5 Findings from the IC-Forum

In order to collect and discuss the findings from current experiments and expertise with the use of internal crowdsourcing in corporations, an ‘IC Forum’ was conducted in the premises of BMBF. Experts from various corporations, scientists, the labour union and NGOs came together and created an overview of the state of the art of IC in corporations in Germany. The IC Forum was a specific form of workshop which enabled participants to bring in their experiences and to get an overview of the early stages and of the different forms of using IC in corporations. The Forum was structured into three phases of intense communication, starting with presentations of the project. During the central second phase, small groups of two or three experts were selected to discuss several aspects of their activities and their experiences. This kind of setting was well suited to creating an atmosphere of open exchange and debate. It is not common for representatives of corporations and other institutions to talk openly about new inventions and new procedures, especially not when this means talking about problems in their work. A broad variety of the existing strategies and procedures for conceptualising, introducing and managing IC in corporations was reported and discussed and finally presented with all experts in the Forum.

It became obvious that practical experiences focused on employee participation, campaign design and competence development. Communication was identified as a key element of internal crowdsourcing and as a success factor. The possibility of personal exchange creates a pleasant comfort zone on the one hand and provides incentives for participation by regularly presenting rewards for good comments on the other. Employee involvement is also an essential point for promoting identification with the company, and it is also important to make the performance and ideas of employees public so that intrinsic and extrinsic motivation come together. These practical activities have positive effects for competence development, mainly because discussing new ideas and approaches strengthens the ability to self-reflect in each employee individually as well as in whole teams. The Forum stressed the fact that the integration and early involvement of stakeholders (works councils, shop stewards, staff councils) are crucial to create trust and transparency. Such involvement is often an additional element and impulse for competence development.

Corporate culture is another important success factor for establishing and developing IC in corporations. Key figures can help to evaluate how many employees are reached and how actively they participate. If there are few employees, it must be asked why this is so, which ultimately leads to the question of culture. Participating in such activities increases the opportunities for employees to detect and utilize their capabilities and their competencies. At the same time, it can also be a step that encourages them to ask management for more specific qualification opportunities (i.e. specific qualification courses).

For a corporation or team to be more competitive, a cultural change in the sense of new work attitudes and requirements is necessary, and this also includes overcoming classic modes of management thinking in the sense of less control, more self-determination, availability of leeway and flat hierarchies, i.e. (‘away from push to pull’). Leadership structures must create trust and joy in work through meaningful and inspiring tasks, and they must enable participation and co-determination. In the sense of efficiency as a success factor, participants also concluded that less control and leadership are not meaningful and possible in all areas and also not for all types of employees. Boundaries and middle ways must be found, and traditional and new leadership strategies must be linked.

The most important factors for successful work processes and ICU are appropriate communication and the early involvement of all employees. Depending on the company and its structure as well as the problem, those instruments and communication channels must be chosen which are able to involve all areas and employees of a company and that allow access for all. Internal crowdsourcing ultimately leads to the democratization of corporate processes and redistributes responsibility within companies. This, however, requires a suitable framework and appropriate support as well as leadership skills that focus on the cost-benefit from an entrepreneurial point of view and can intervene if necessary.

3.6 First Conclusions and Approaches to Qualification, Further Training and Competence Development

The results from the previous interviews provide important insights into the perspectives of the employees and members of GASAG’s management surveyed. The statements regarding previous experience with qualification and further training measures as well as expectations and wishes for future qualification, further training and competence development are particularly relevant. They are to be used in addition to the theoretical findings described in chapter “Introduction to ‘Internal Crowdsourcing: Theoretical Foundations and Practical Applications’”.

From the combination of the elaborated theory and empiricism, framework conditions can now be derived which are to be taken into account in the development of an application-oriented concept. The following aspects are therefore part of the framework conditions:

-

An introduction to the topic of competence development through internal crowdsourcing as well as employee participation should take place at an early stage and at low thresholds in order to arouse interest and achieve long-term support.

-

Measures for qualification, further training and competence development through internal crowdsourcing should not replace current further training measures but complement them and offer starting points for reviewing the previous further training programme.

-

The approaches should be closely geared to the working reality of GASAG employees and aim to create practical added value for day-to-day work.

-

The expansion of digital skills, especially the use of digital application software, should play a special role in the design of measures.

-

The establishment of an internal company network, a transfer of knowledge and an exchange between employees from different departments and areas are central elements of the application-oriented concept.

-

Findings from competence research and open learning environments are also taken into account, as is criticism of a too rigid orientation towards the competence concept.

-

Participation in measures for qualification, further training and competence expansion through internal crowdsourcing are basically voluntary and take place anonymously or pseudonymously.

-

There is no internal ‘employee ranking’ on the basis of competence by the company management, but an overview of existing competencies in the company should be facilitated.

-

Employees should be given the opportunity to discover their individual competencies and interests, to develop them further and to articulate existing qualification, further training and competence development needs and to make use of appropriate measures.

4 A New Concept for Qualification, Further Education and Competence Development through IC: Results and Options for Action

Considering the needs, interests and framework conditions listed in section “The Crowdsourcing Process” for an application-oriented concept for qualification, further training and competence development, three approaches are proposed below, each of which involves working on a task in the digital crowdsourcing application:

-

1.

An employee crowdvoting to collaboratively assess and prioritize competencies

-

2.

A multiple choice test to assess existing knowledge and skills and to impart knowledge

-

3.

The use of crowdsolving/crowdcreation processes for competence development and as a starting point for promoting knowledge transfer and an internal company network

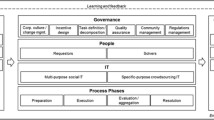

Approaches 1 and 3 are based on general types of crowdsourcing tasks already defined for the project. Approach 2 deviates from these task types but makes use of the technical possibilities already offered by the Crowdee platform provided by the Institute for Software Engineering and Theoretical Computer Science/FG Quality and Usability Lab (QUL) and serves as a useful addition to a company’s traditional continuing education programme. The following is a possible application of these three approaches, which together form the basis for the application-oriented concept of qualification, further training and competence development through the use of internal crowdsourcing (Fig. 2).

4.1 Crowdvoting

In order to provide an initial introduction to the topic of competence development through internal crowdsourcing, an anonymous employee survey based on a crowdvoting process is proposed. Participants are given the opportunity to provide their assessment of the relevance of different competencies. A list of competencies is derived from the existing competence model of the company. From this list, the employees can select five competencies which they consider to be particularly relevant for their own work within the next 5 years. It is also possible to make further suggestions, leave comments or ask questions by freely entering text. Subsequently, the results are evaluated by the crowdmanager, and the resulting need for action or qualification is derived and communicated. The employees are given the opportunity to comment on and discuss these results and proposals for action again in the crowd.

This approach serves as an introduction to the area of competence development and internal crowdsourcing and allows employees a low threshold introduction to dealing with a new digital application. Crowdvoting gives employees the opportunity to participate in a common prioritization of competencies and thus to participate in the process of identifying focal competency aspects within the scope of later competency development measures. The results of crowdvoting, i.e. both the ticking behaviour and the comments in the free text input, will be used to check GASAG’s current range of qualification and further training courses and, if necessary, to adapt or add to them. Together with the results from the interviews, the crowdvoting results provide indications for aspects which need special consideration in the development of a multiple choice test (see section “Methodology”) as well as in the development of the approach for crowdsolving/crowdcreation (see section “Synthesis of the Literature”).

They provide information as to which competencies should be given special consideration from the point of view of the participants. Finally, this approach supports transparency and strengthens an open corporate culture and a ‘sense of unity’.

The crowdvoting process consists of two phases: one is the survey phase, i.e. the actual ‘voting’ by the employees. This phase should extend over a period of at least 2 weeks in order to give the employees sufficient time to answer the questions. Afterwards, the crowdmanager evaluates and prepares the results, which is followed by a second participation phase, i.e. the possibility to submit queries, further comments or ideas on the results. This should, in turn, extend over a period of at least 2 weeks. Alternatively, an unlimited commenting function is also conceivable, whereby the crowdmanager should regularly check any comments and, if necessary, answer and use them (Fig. 3).

A further clarification of the procedure also depends on the specific structures in the organization in which the IC campaign is to be carried out. These include questions such as the time period in which the survey is to take place, how comprehensively the results are to be processed, on which further communication channels (i.e. beyond the crowdsourcing platform) the results are to be communicated, how crowd management is to be organized and which person(s) is/are responsible for it, etc. In what timeframe is the IC campaign is to be carried out? A possible variant can be illustrated on the basis of a first implementation of such a crowdvoting with the focus on the topic ‘competencies’ by the industry partner GASAG within the framework of the ICU Project.

4.2 Multiple Choice Test

This approach gives employees the opportunity to take part in a standardized multiple choice test via the crowdsourcing platform. On the one hand, employees’ basic knowledge on a previously defined topic is tested, on the other hand decisions concerning alternatives for action in certain work situations weighed up, while the way that solutions are selected and justified is evaluated. In preparation for the multiple choice test, in-depth information material can be made available via online links and compiled according to the focus of the subject. Following participation, the employees receive a certificate which proves their knowledge and skills in the respective field (Fig. 4).

A multiple choice test includes questions on how to use digital application software, on facts and areas of work in the respective industry (here: energy industry) or on other topics relevant to the majority of employees. With the answer to the last question in the test, the participants receive a test evaluation and the option of receiving a certificate, which identifies them as one of four different role types (high potentials, team workers, experts and consultants). The evaluation of the individual response behaviour shows which questions were answered correctly, which were answered incorrectly or incompletely, and contains links via which employees can directly access teaching materials on the relevant topics.

Irrespective of the respective content, a multiple choice test like this always aims to assess and expand specialist knowledge as well as technical and methodological skills. Participation in the survey is an independent further training measure, which is certified by awarding a certificate. Employees can take the initiative to participate in the survey at any time and thus check their own development and progress in the respective subject areas. If they identify a need for further development, they can contact their superiors and discuss opportunities for further training. Awarding a certificate offers direct and visible added value for employees.

In addition, the collective response behaviour provides conclusions on the strengths, potentials or needs of the workforce, which can be used to regularly review the company’s further training programme and adjust it if necessary. It is also conceivable that ‘high performers’ in this test be networked with employees who have personally identified a need for further training. Such persons could provide support and help with questions and problems.

The effort required to develop such an approach is manageable, and the effort required on the part of the company is also limited, since the evaluation of the multiple choice test is largely automated after implementation. Time and effort are required above all when designing the survey, when providing follow-up support in the event of a possible need for further training and (if desired) when developing of appropriate teaching materials. All employees are free to participate at any time. However, it is also conceivable, for example, to limit participation to a maximum of one employee per month. With regard to the amount of time, the use of self-developed or externally developed teaching materials, the thematic orientation, etc. different alternatives are possible depending on the preference and orientation of the company. The issue of certificates or the handling of the results must be clarified based on the company situation and can be designed differently.

4.3 Crowdsolving and Crowdcreation

The voluntary participation of employees in the processing of a task over a defined period of time initially intends to promote the (further) development of innovative products, services or processes. Within the framework of the application-oriented concept, crowdsolving and crowdcreation should also contribute to the systematic development of employee competencies. This is based on our following assumption:

Crowdsolving and crowdcreation processes provide information on existing competencies of the participating employees as well as on possible competence requirements on the part of the company.

A case study would require either participation in the solution of a problem (crowdsolving) or the development of ideas for an innovation (crowdcreation). In order to create access to the area of competence development via the processing process, different competencies are to be defined which are necessary for the successful processing of the case study. Thus, it is possible to identify employees with particularly pronounced competencies, as long as they are interested and willing to take part.

Just like the other two approaches, voting and multiple choice, this approach also offers points of reference for reviewing current continuing education activities within the corporation and supplementing them with explicit learning activities. Every employee has the opportunity to discuss individual qualification options with their superiors. The decisive question now, however, is how exactly or on what basis (further) development of employee competencies can take place and what conditions must be met. The key to this lies in networking the employees, transferring know-how and, above all, in cross-departmental cooperation in heterogeneous project teams assembled according to specific characteristics. These areas should therefore be at the centre of the competence development strategy (Fig. 5).

Against this background, competence development can be realized on at least two levels: on the one hand, on the digital level, by playing solution paths back into the crowd and incorporating several feedback loops in order to initiate a process of dialogue or reflection concerning joint work. In addition, the employees gain a better systemic understanding of the company and can position themselves more consciously in it. On the other hand, on the face-to-face level, the crowdsolving/crowdcreation tasks are further processed in ‘real’ and cross-departmental project teams. As explained in section “GASAG Group”, a promising further development of competencies should take place ‘on the job’, i.e. under real working conditions—not least because of the importance of the meaningfulness of such an activity. In such a context, not only the mere application of (specialist) knowledge is required but rather a combination of this knowledge with personal experience, skills and abilities and further individual characteristics with regard to a specific question or problem.

This approach is similar to the action learning approach, in which employees learn a realistic task by participating in a solution to be worked out together and reflect on this work and learning process at the same time (Revans 2012). Against the background of a desired competence development, an expansion of the joint work on concrete questions in project teams therefore appears to be a format that makes particular sense.

The topics that are dealt with in the context of crowdsolving and crowdcreation serve as a content resource for the project teams, where they can be dealt with more intensively and systematically, using and continuously developing the competencies of individual team members. The response and dialogue behaviour of the participants in crowdsolving and crowdcreation tasks can be used to obtain information on the development of competencies. This information can in turn help when putting together the team to further process the task.

In order to promote an internal transfer of knowledge within the company and to stimulate possible impulses and provide employees with food for thought outside of the project teams and outside of the participants in the crowd tasks, the results of the project work should again be made available to all employees of the company in an appropriate form. Systematically documenting the work performed in the project teams and—with the consent of the participants—providing an overview of the participating team members and their roles also provides a valuable resource for the work of strategic personnel development.

In summary, this strategy results in a three-step process to enable qualification and competence development through crowdsolving/crowdcreation:

-

1.

In a first step, a searching process has to be conducted to gather evidence of strong competencies. This process focuses on the responsiveness of participants in the crowdsolving and crowdcreation tasks or projects.

-

2.

For the crowdsolving and crowdcreation process, project teams have to be formed which organize themselves during the course of the project. Participants can apply and develop their competencies, or they can discover new ones.

-

3.

After such a crowdsolving and crowdcreation project, the project results should be published through relevant channels for all employees in the company.

4.4 Identifying Competencies: Crowdsolving and Crowdcreation as an Instrument to Identify Competencies

In terms of competence theory, crowdsolving and crowdcreation tasks are also characterized by the fact that they do not simply involve querying knowledge but rather initiate a discussion and work process for a real or realistic task. The solution of such a task profits from the cooperation of the participants and the mutual picking up on and discussing of discussion contributions. Within the spectrum of conceivable crowd tasks, crowdsolving and crowdcreation processes are therefore particularly suitable when searching for hints pointing towards competencies and their characteristics.

The first step will therefore be to gain information on the development of certain competencies based on the participants’ response behaviour. This is because it is generally difficult to make unambiguous statements about the undoubted development of certain competencies. Nevertheless, the response and solution behaviour of the participants allows conclusions to be drawn as to which of the competencies sought could be strongly developed or which of the participants have promising potential to develop the competencies sought. Such assessments tend to be subjective in nature but can be limited by taking into account previously defined criteria.

With every crowdsolving/crowdcreation task, the first question that arises is: Which competencies are required to successfully complete this task? Therefore, the competencies that appear necessary to solve a task should be defined in advance. This usually includes competencies or areas of competence that are generally helpful in dialogue-oriented processes, such as collaborative and communicative competence or the ability to put oneself in other perspectives. In addition, competencies should be defined that are necessary for solving this specific task, such as technical or methodological competencies for a specific manufacturing process, process-oriented competencies for specific work processes or entrepreneurial competencies.

In order to gain suitable clues for an assessment of when or under what conditions a competence could be particularly pronounced, criteria must be formulated that can be applied when searching for hints pointing towards the existence of the previously defined competencies. For this purpose, the concept of action anchors (also known as ‘behaviour anchors’) is used, which is described by Erpenbeck and Sauter, Obermann and others (see section “GASAG Group”). Such action anchors describe certain perceptible behaviour patterns, which in turn allow conclusions to be drawn about competencies. For example, for the competence ‘result orientation’, action-related statements such as ‘sets own priorities and acts accordingly’ or ‘derives suitable measures for own goals’ can be derived. For the assessment of the competence ‘ability to work in a team’, on the other hand, statements such as ‘also works together with others in competitive situations and helps them’ or ‘balances differences in the group and contributes to a common solution’ help. Such statements are formulated for each of the competencies that were previously identified as necessary for solving the respective task.

After a crowdsolving/crowdcreation campaign has been completed and all participants have submitted their contributions and participated in the work process, the response and solution behaviour of the participants can be evaluated on the basis of the assessments of personnel managers with the help of the action anchors. The contributions are examined in terms of both content and interaction with other participants according to their respective competence. At Sauter and Staudt, the assessment of competencies with regard to the anchors for action is carried out on a scale with values from 1 to 5, whereby 1 is awarded for very weakly developed and 5 for very strongly developed competencies (Sauter and Staudt 2016b, p. 16).

Against the background of the debate about an internal ‘employee ranking’ and with regard to the statements from the interviews with members of GASAG’s management and the negotiated group works agreement, however, an assessment of competence levels below an average can be regarded as critical. Such an individual assessment could, despite the use of pseudonyms, trigger concerns among employees. Such an individual assessment could, despite the use of pseudonyms, raise concerns/fear among employees and ultimately lead to little or no participation in crowdsolving and crowdcreation tasks. In any case, the main aim of this approach is to identify those employees who have a distinct need in specific areas in order to specifically support them in developing their competencies. In order to prevent corresponding concerns about negative evaluations, an evaluation should only be carried out (and also documented) by those participants who are suspected of possessing a strong development of the competencies in question or who are prepared to disclose and promote these.

However, the employee contributions do not only provide information on the characteristics of possible competencies. They also offer the opportunity for further insights, especially into the areas of interest and the aptitudes of employees for certain topics and questions. Such findings are valuable both for the personnel managers and for the employees themselves, who may not have had the opportunity before to deal with such topics and questions. The presumed level to which certain competencies are developed is therefore only one indicator to be thought about when considering employees for the later composition of project team, for example. Interest, understanding and commitment can also be important conditions for this.

A possible alternative to take even greater account of the commitment and interest of the employees when putting together the team, and at the same time to further reduce concerns about an internal employee ranking, is to open an internal application procedure. After the crowd process, the participating employees are given the opportunity to apply for participation in a topic-specific project team. Only after the application has been received would the individual response behaviour be evaluated and, for example, an interview with the project team leader offered. If there is mutual agreement on the development potential and possible development goals with regard to competencies, the candidate can be included in a pool for a project team to be formed at a later date.

Irrespective of the concrete design of the process, the ultimate goal of this first step is to consider those employees who are assumed to have strongly developed the competencies in question and those who show a particular aptitude and commitment in the context of crowdsolving and crowdcreation for inclusion in a respective employee pool. In the next step, the project teams can be put together from this pool after consulting the HR managers, crowd managers and topic experts.

4.5 Developing Competencies: Formation of Topic- and Project-Specific Teams

In a next step, project teams can be formed that systematically deal with the previously set crowdsolving/crowdcreation task over a certain period of time. Regular cooperation in such teams promotes an exchange of knowledge and enables employees to use and develop their skills in a targeted manner. Teamwork is accompanied by the use of teaching materials and appropriate further training measures for the team members. Joint teamwork thus represents a form of learning integrated into the process, with knowledge acquisition and competence development taking place on the basis of concrete work processes.

In order to put together a team that has both the potential to work efficiently on the respective topic or concrete task and sufficient flexibility to organize itself to a large extent, the size of the team should be manageable and range from a minimum of five to a maximum of ten members. The team is composed of employees who can, if possible, be assigned to the following four types, among others: high potentials, team workers, experts and consultants. While members of the first two categories are identified from the group of participants in crowdsolving and crowdcreation tasks, members of the last two categories can also be those who have not yet participated in internal crowdsourcing. The four role types in work teams can be described as follows:

-

1.

High potentials: Participants in the crowdsourcing task whose technical or methodological competence level was assessed as strong to very strong, i.e. who showed a special understanding of the task at hand and made high-quality and solution-oriented contributions.

-

2.

Team workers: Participants of the crowd task whose social competence level was assessed as strong to very strong, who, e.g. respond in a special way to the contributions of others and develop them further, who have an integrative and constructive effect or who have special communicative strengths.

-

3.

Experts: Employees who, due to their work in the company, have special specialist skills and whose department is usually responsible for the content of the corresponding task. The team’s project leader should also be appointed from this group, and this person should at the same time serve as a coach or mentor. In addition to a balanced distribution of work and adherence to project goals, the project management must also ensure smooth communication, motivation and the involvement of all team members.

-

4.

Consultant: Employees who have many years of professional experience and are particularly familiar with certain processes and earlier project phases but who have not yet participated in the ICU process.

Such a heterogeneous team composition, in which the individual team members contribute their respective strengths, promises great solution potential with regard to both the development of innovative solution approaches and the further development of employee competencies. All team members should take on active roles in the team and be responsible for handling concrete tasks. The combination of experts, crowdworkers and consultants already results in different roles within the team. The distribution of tasks can result in an organic process during the first meetings, but it is ultimately the responsibility of the project management.

In addition to the question of which participants from the crowdsolving/crowdcreation process and which other employees from the company should be integrated into a team, there are a number of other questions that should be clarified during the project planning phase. These include:

-

What is the aim of the project, both in terms of the task to be completed and in terms of the development of employee skills?

-

How long is the project expected to last?

-

Which time capacities must be planned for the project team and can be realized with the selected project members?

-

Which departments are affected by the composition of the team and with which areas of responsibility must this be clarified?

-

Are there tasks in the project that cannot be solved by the team but have to be solved externally?

-

How often should (or can) there be joint project meetings considering everyday tasks?

-

What is the relationship between individual team members?

-

How should the project work and the results achieved be documented, made accessible or published in the company?

The answers to such and similar questions depend to a great extent on the structures and organizational culture in the respective company. A general clarification of these questions—and thus the creation of appropriate framework conditions—is always necessary in order to facilitate smooth, constructive and trusting cooperation. However, the work in the project team should not be ‘overregulated’ under any circumstances. Particularly against the background of the desired competence development and the creative and intellectual development, a high degree of organizational freedom is indispensable.

In this context, the idea of a self-organising team, as described by Klein (2010), seems to provide an interesting reference. Such teams independently plan, review and improve their work processes, set their own goals and create their own work plans. They also assess their performance in group discussions, coordinate cooperation with other departments and take care of the professional training of their members. The principle of a self-organising team would seem to make sense in this context of innovation and competence development—and under the premise that the framework conditions mentioned above are created.

4.6 Disseminate Knowledge: Documentation of the Project Work and Internal Publication of the Results

The results achieved in the project teams are not only relevant for company management. The knowledge produced can also offer exciting insights into new areas for the other employees of the company or provide an impulse for new ideas—or at best even contain important information for one’s own work. In addition, it makes sense to make the team members and their tasks known to other employees as well, since they can develop into ‘experts’ for the respective topic and serve as possible contact persons—and thus gain recognition. Last but not least, the transparency lived in the company also suggests that every employee in the company should have the opportunity to access the results and be given an overview of the team members involved. This should also improve the corporate culture.

In order to enable the results to be disseminated within the company, various questions have to be clarified. First of all, project work has to be documented: Who should take the minutes? What exactly should be documented in what frequency and with what level of detail? Which system and which medium should be used? Answers to these questions depend on the respective project as well as on the documentation methods normally used in the company. Decisions between alternatives should be made by the team leader.

The central questions are ‘How’ and ‘Where’: How should the results be prepared so that they are informative, useful and understandable for all employees? And where, i.e. on which platform or using which medium, should the results be published? A clear text in three sections is recommended for the type of preparation. First, the project background, the relevance for the company, and the respective topic should be explained as well as the question and the underlying crowdsolving or crowdcreation task. Then the results (possibly supplemented by visualizations) should be summarized, and finally a concise explanation should be given of what the results are used for in the company and what the next steps will be. In addition to a clear presentation of results, it is also important to clearly and comprehensibly embed the use of results in the company context.

An advanced and more complex variant would be to develop a knowledge and competence platform that would also access the intranet and use it as a framework architecture but with its own system and extended functions. In addition to a more detailed presentation of project work, the platform could also include a glossary explaining key terms and an overview of employees who have worked in project teams or are designated as contact persons for specific topics. In addition, it is possible to tag contributions (= keywords) and link terms. Such a knowledge and competence platform would thus correspond in its structure and logic to a company wiki, i.e. an open knowledge environment that could be continually expanded over time and whose benefits would increase with increasing input. However, the detailed conception, development and continuous maintenance of such a platform require extensive time capacities and a corresponding budget.

In addition, other internal communication channels should also be used to draw attention to the project results or their publication or significant progress, especially to employees who have not (yet) participated in crowd activities. These include articles in a newsletter, in the company magazine or information via the internal email distribution list (Fig. 6).

5 First Results and Perspectives for Competence Development Through a Combination of Virtual and Face-to-face Working Processes

The approach which was observed and analysed within the ICU Project is very new, and there are only few corporations using and working on and with the approach of internal crowdsourcing and digital platforms. This is the reason why the empirical basis for this study was rather small, and, because of this, the findings and the interpretations derived have to be articulated carefully, acknowledging the given context of the research project.

When introducing internal crowdsourcing tools and the associated opportunity to develop employee competencies, companies are confronted with a spectrum of challenges and obstacles which have to be overcome and managed. Most often, long-standing routines, communication procedures, decision-making processes and working patterns have to be changed and transformed.

One basic challenge is related to a kind of contradiction. When establishing internal crowdsourcing tools and grasping the associated opportunity to develop employee competencies, companies and specifically their management find themselves in an arena of conflict between control and democratization, hierarchy and participation, top-down culture and motivated-active employees. Therefore, the early involvement of shop stewards and employee representatives (works council, staff council) is extremely important. Such innovations have to be institutionalized and defined in the contracts.

In order to achieve effective competence development, (virtual) work using digital collaboration tools should be combined with face-to-face teamwork process. This is to some extent relevant because some personnel may not be trained or equipped to handle and manage the intranet and other platforms. Digital collaboration must also be embedded in the already existing and established organizational structures of the company in order to find resonance and effective utilization by a majority of employees.

The organization of certain work processes in self-organising project teams requires a high degree of self-discipline from the employees and a fundamental openness of the management towards flexible work structures as well as regarding roles, hierarchies and responsibilities. This should be supported by the management adequately, for instance, though routine staff meetings or staff appraisals. This is an additional contribution towards competence development.

The use of internal crowdsourcing and digital collaboration tools for competence development is particularly suitable for larger companies with a large number of employees. There is, in particular, potential to reveal and consequently promote previously hidden competencies of employees if this is in their own interest and if they ask for such courses or training.

The specific process approach to competence development through internal crowdsourcing enables both the promotion of employee competencies on an individual level and an internal networking of employees and knowledge transfer on a broad collective level. Taking all this together can lead to an advanced and improved corporate culture and more job satisfaction—and to a better overall performance of the corporation.

Based on the tentative impressions and analysis of the examples of digital collaboration in corporations, it can be expected that such approaches will be used much more often in the near future, especially in corporations with young and open-minded employees and management. However, the experience described and discussed here shows that certain lessons learned should be taken to heart in order to bypass obstacles and conflicts. Additional research in this field is necessary to help understand and reflect on the rapid introduction of digital collaboration approaches in corporations and other institutions for the competence development of employees, which is much more necessary than it already has been in the past.

Notes

- 1.

In the ICU project, this was a separate Crowdsourcing Platform (‘GASAG IDEENlabor’).

References

Baitsch C (1996) Kompetenz von Individuen, Gruppen und Organisationen. Psychologische Überlegungen zu einem Analyse- und Bewertungskonzept. In: Denisow K, Fricke W, Stieler-Lorenz B (eds) Partizipation und Produktivität. Zu einigen kulturellen Aspekten der Ökonomie. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Bonn, pp 102–112

Barth M (2008) Das Lernen mit neuen Medien als Ansatz zur Vermittlung von Gestaltungskompetenz. In: Bormann I, de Haan G (eds) Kompetenzen der Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung Operationalisierung, Messung, Rahmenbedingungen, Befunde. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, pp 199–213

Bolder A, Dobischat R (2009) Objekt oder Subjekt von Wissensmanagement? Was bringt uns die Publizierung der ‘heimlichen’ Qualifikationen? In: Bolder A, Dobischat R (eds) Eigen-Sinn und Widerstand. Kritische Beiträge zum Kompetenzentwicklungsdiskurs. Springer, Wiesbaden, pp 7–18

Borner J (2008) Die Entwicklung und Strukturierung des Kompetenzbegriffes – Von der Qualifikation zur Kompetenz. Kolleg für Management und Gestaltung nachhaltiger Entwicklung, Berlin, pp 1–8

Bunk G (1994) Kompetenzvermittlung in der beruflichen Aus- und Weiterbildung in Deutschland. In: Europäische Zeitschrift für Berufsbildung, vol 1. Begriff und Fakten, Kompetenzen, pp 9–15

Erpenbeck J, Heyse V (1996) Berufliche Weiterbildung und berufliche Kompetenzentwicklung. In: Arbeitsgemeinschaft Qualifikation-Entwicklung-Management (ed) Kompetenzentwicklung 96: Strukturwandel und Trends in der betrieblichen Weiterbildung. Waxmann, Münster, pp 15–152

Erpenbeck J, Rosenstiel v L (2007) Handbuch Kompetenzmessung. Schäffer- Poeschel, Stuttgart

Erpenbeck J, Sauter W (2016) Stoppt die Kompetenzkatastrophe! Wege in eine neue Bildungswelt. Springer, Berlin

Kaiser A (1998) Carte de competence: Wie lassen sich Kompetenzen feststellen? In GdWZ 5:199–201

Kaufhold M (2006) Kompetenz und Kompetenzerfassung. Analyse und Beurteilung von Verfahren der Kompetenzerfassung. VS Verlag, Wiesbaden

Klein A (2010) Projektmanagement für Kulturmanager. Springer, Wiesbaden