Abstract

Many old adults are faced with the risk of social exclusion, which inhibits them from enjoying a satisfactory quality of life. Accordingly, understanding this multidimensional and multifaceted complex phenomena is crucial for building an inclusive society. Hence, studies concentrating on vulnerable groups with higher probability of economic forms of exclusion, such as widowed or divorced materially deprived women, are valuable as exclusion necessitates different actions for different segments of the older population. Against this background, this chapter investigates resilience and coping mechanisms of materially deprived widowed and separated/divorced older women. Data is taken from a qualitative study in Turkey and Serbia, two EU candidate countries with different enabling environments and social protections for older people, but with a similar level of connectedness within extended families. Semi-structured in-depth interviews with materially deprived divorced and widowed women, aged 65 years and older were conducted. The data was analysed based on the framework method. The analysis identifies the economic exclusion experienced by these women, along with the resilience and the different coping mechanisms that they demonstrate. Furthermore, it makes a cross-country comparison between Turkey and Serbia laying out similarities and differences between the two nations on this topic.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Social exclusion goes beyond “depleted budgets” (Sen 2000) and involves broken social ties and marginalisation of specific groups in mainstream society (Sheppard 2012). It is both a dynamic process (Scharf 2015) and a multifaceted phenomenon (Levitas et al. 2007) manifesting in various aspects of social life (Walsh et al. 2017). Many adults are at risk of old-age social exclusion due to a higher probability of losing independence (Kneale 2012), reduced income, chronic disability and ageism (Phillipson and Scharf 2004). Amongst the older population some individuals are thus more prone to social exclusion, and its economic components (Barnes et al. 2006). While older women experience inequalities throughout their life (Sataric et al. 2013), disruptions such as divorce, separation and widowhood can exacerbate inequalities for previously married women, as it presents a reduction in income (Myck et al. 2017) and a drop in living standards (Calasanti 2010). It may affect housing decisions, downsizing and co-residing (Wagner and Mulder 2015).

Coupled with the challenges that old-age can bring (declining health; increased likelihood of bereavement, etc.), economic exclusion poses a threat to older people’s capacity to pursue an independent and satisfactory quality of life (Whitley et al. 2018). Yet, some older people can adapt positively to adversely changing situations and can demonstrate a substantial capacity for resilience, as an “ability to incorporate both vulnerabilities and strengths across a range of areas and time frames” (Wiles et al. 2012, p. 243). This is also true for older adults with socio-economic disadvantages (Kok et al. 2018), and those faced with economic shocks (Fenge et al. 2012). While not all individuals can cope with such economic adversities (Bennett et al. 2016), understanding the coping mechanisms of older people who do adjust are important for devising policies and interventions for mitigating vulnerabilities and building more inclusive societies.

This chapter explores the economic exclusion experiences and coping mechanisms of materially deprived divorced, separated and widowed older women living in Serbia and Turkey – two countries whose ageing populations have received little study within the international literature. The two countries have many common cultural and social traits and family structure; such as extended families (Georgas 2006) and strong family ties (Ferra 2010). In both countries, older men fare better than women in many life domains, including employment and financial security (UNECE 2016). However, while Serbia is among the oldest populations in Europe (with 18.2% of people aged 65 years and over), Turkey is in comparison one of the youngest (with 8.7% of people aged 65 years and over) (United Nations 2019).

Previous research has examined resilience of older adults, especially with regards to health outcomes (Van Kessel 2013). More recently disadvantaged communities and groups (Thoma and McGee 2019) were also investigated. However, resilience and coping mechanisms of one of the most vulnerable older groups, materially deprived widowed and separated/divorced women, in the face of economic exclusion have never been studied in Turkey nor Serbia, with also little attention given to this topic in other jurisdictions. Drawing on a qualitative study, the chapter addresses four questions. Firstly, what are the economic exclusion experiences of materially deprived widowed and separated/divorced older women [also see Sumil-Laanemaa et al. this section]? Secondly, while these women are among the most vulnerable, do they demonstrate resilience vis-à-vis economic exclusion? Thirdly, if they do so, what coping mechanisms do they employ? Fourthly, how do similarities and differences in Serbian and Turkish contexts shape coping mechanisms of these women? We begin by outlining the qualitative study that underpins our analysis. This is followed by a description of the findings of the research, focusing on early life experiences, life during marriage, and life after disruption to marriage (e.g. bereavement; separation; divorce). Finally, a discussion and conclusion are presented.

2 Methodology

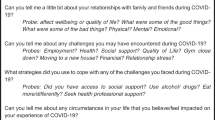

Data was collected through 11 semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted in Serbia and 16 conducted in Turkey during August and September 2019. The interview guide consisted of questions regarding: (1) socio-economic background; (2) current daily and social life; (3) economic and financial circumstances throughout the life course; (4) life with husband and family; and (5) changes experienced after disruption of marital ties, as well as fulfilled or unfulfilled aspirations and experiences of loneliness and exclusion. The questions were broad so as to allow participants to elaborate and express their experiences and perceptions freely.

The interviews were conducted in two cities in Serbia (Belgrade and Kraljevo) and two villages (Ćuvdin and Žiča) and three provinces in Turkey (Edirne, Mersin and Istanbul). A responsive interviewing approach was used, where researchers were flexible and adjusted to the personalities of the participants (Rubin and Rubin 2012). The interviews were audio recorded and lasted one hour approximately.

2.1 Recruitment and Participants

Participants were recruited through purposive sampling based on five criteria: (1) being older than 64 years; (2) being female; (3) being widowed, divorced or separated (not legally divorced, living in separate household with no expectation of unification); (4) having good cognitive functioning (able to rationally answer the questions) and (5) being materially deprived/facing economic exclusion. For material deprivation, the 9-item scale of Eurostat (2019) was used.

With reference to Table 5.1, most participants were aged 65 to 69 years. Around three quarters were widowed, with the remaining six participants being separated or divorced. One third of the sample lived in rural areas. Most participants had two children and more than half co-resided with children or grandchildren. More than half from Turkey possessed literacy issues, while half of Serbian participants completed high-school. Most participants married under the age of 18 years and around three quarters of the sample had a pension of their own or a pension from their husbands or fathers.

2.2 Data Analysis

After completion of all interviews, audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by the researchers. The framework method, efficient in multi-disciplinary research, which provides clear steps to follow and produces highly structured outputs (Gale et al. 2013) was used for the analysis. Following Ritchie et al. (2013), transcriptions were read, and themes were identified by the researchers separately. Themes identified by more than two researchers were included in the analysis. Using NVivo 12, transcriptions were coded and categorised by two researchers from each country. A framework matrix was developed for each country. Based on the matrices’ similarities and differences between the countries and variance in lived experiences were identified.

2.3 Ethical Considerations

The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Municipal Institute of Gerontology and Palliative Care in Belgrade, Serbia, and the Ethics Committee of the Gebze Technical University, Turkey. While the consent of study participants was obtained in writing from the literate interviewees, oral consents were audio recorded for those who had literacy issues. The researchers were also careful not to raise any expectations amongst participants for the improvement of their circumstances.

3 Findings

Three main themes corresponding to the different phases of participants’ lives emerged in interviews, namely: early life experiences, life during marriage, and life after marital disruption. Unless otherwise stated these themes were robust across widowed and separated/divorced participants in both countries.

3.1 Early Life Experiences

Except for a small number of participants in Turkey and Serbia, participants experienced multiple disadvantages during their childhood, namely financial insecurities, material deprivation and gender inequalities. Marrying early at the ages of 14–16 years and receiving little or no education are manifestations of these gendered inequalities. Turkish participants, particularly those with little formal education, talked about education in relation to gender inequalities and missed opportunities:

‘Back then, women were to marry early…So they said there is no need for girls to go to school. Us, four sisters did not go …. My brothers went. We could not.’ (TE04).

Faced with financial insecurities, participants raised the issue of working at an early age. Working as an unpaid household worker in the fields and orchards and engaging in domestic work were experiences shared by all participants in the rural and poorer areas in both countries. Some also provided care for younger siblings so that their mothers could work.

3.2 Life during Marriage

Within the scope of discussions during married life, participants mostly talked about their financial situation at the time and strategies they employed to cope with financial troubles.

3.2.1 Financial Situations

Although the degree and timing varied, most of the participants experienced economic exclusion. For instance, while one participant in Turkey stated that “I always had financial problems...” (TM09), another participant stated that financial problems started “when he [referring to husband] closed his shop after he got sick” (TM07). At times, these financial problems were accompanied by marital troubles such as economic abuse (e.g. denying access to financial resources), the husband’s extra-marital relations or gambling. For instance, a divorcee housewife stated that her husband started acting out of the ordinary and held her responsible for financial problems. “My husband did not shop for the house, did not buy food, did not buy anything for the house and anything kids wanted” (TM12).

Participants living in impoverished neighbourhoods indicated that they had to work very hard to cope with economic hardships. Migrating to urban from rural settlements was also a marker of financial issues according to the respondents; “When we came to the city, our savings slowly melted away” (TM08). Precarious housing conditions at the start of the marriage was regarded as an indicator of low economic standing in both countries, and contrasted with the relative increase in standards of living experienced by some participants more recently: “It is good now, I have a bed, I have a bathroom, I was sleeping on the floor.” (RSV2). Connected with material security, buying a house was a core objective in both countries.

3.2.2 Coping with Economic Exclusion During Marriage

Because of this experience of economic hardship during their married life, participants talked in detail about their coping strategies. The most dominant strategy employed in both countries to address, as well as cope with, economic exclusion concerned work and particularly increasing working-hours, with some individuals having to go to extensive lengths to reconcile work and family responsibilities:

‘And how did I spend my life? One child on my back in the cradle, another in my arm, bag on my back and go walking one hour to the field, to work …I can’t regret how I spent my life.’ (RSV2).

When they received income, they spent it on children or domestic needs. In Turkey, almost all those working in their early married life worked in precarious jobs. Working in registered jobs with social security benefits was rare, even in later periods. Most participants did not have social security and access to pensions based on their work. While working conditions of the participants were not any better in Serbia, all participants contributed to a state pension fund to gain an entitlement to receive a pension in later life, albeit at the basic level.

In rural Serbia and Turkey, participants mostly worked in cleaning, agriculture and handcrafting industries. However in the cities (Serbia), clerical work and teaching were the dominant professions. To make ends meet, combining more than one job in a day was a strategy in both countries engaged in by several participants:

‘I used to work three jobs a day. Sometimes I went to two houses to clean. Later, I went to wash dishes at a restaurant. If I was not tired late at night, I used to knit’ (TM01).

When participants’ husbands were sick, or when in some cases their husbands’ neglected their familial responsibilities as the main bread earner in highly patriarchal societies, participants increased their efforts to earn money. However, some husbands in Turkey banned their wives from working.

In desperate times, converting assets to cash was another strategy employed by interviewees to cope with economic hardship. After migrating from a rural village, one Turkish participant had to sell her beloved rug: “I did not have much choice, either give up the rug or spend one more hungry night with my kids” (TI15).

Living with other relatives was another important coping mechanism. Some shared the same house with their parents, or parents-in-law. This typically meant an increased domestic workload, but also often enabled them to work outside the house as they had someone to take care of their children. In times of economic hardship, family members and relatives provided financial and in-kind support in both countries while support from friends and neighbours were limited and on an ad-hoc basis. Participants who were working as a domestic worker were able to diversify sources of support, getting help from their employers:

‘The house owner was a doctor. He would help me whenever we needed to go to hospital. His friends would also help me’ (TI14).

3.3 Life After Disruption of Marriage

3.3.1 Finances

All participants had a low income. In Serbia, the main source of income was participants’ personal pension, or that of their late husband’s where an interviewee was widowed – if the husband’s pension was higher than a participant’s, which was frequently the case, she sought to receive his pension instead of her own. The sources of income were more diverse in Turkey and included personal pensions, pensions from the husband or father, or social assistance such as widowhood and old-age allowances. As formal social security registration was not prevalent, many women were not entitled to a pension based on their own labour. “I couldn’t register [for] social security. I could not get that kind of job” (TE04). In one case, a participant was working in a family shop, but the husband was registered with the social security.

Some participants in Turkey, who did not have any sources of income, applied to and received social assistance, like old-age or widowhood allowances. Participants living in more disadvantaged neighbourhoods received ad-hoc financial and/or in-kind aid from municipalities (food stuffs, and coal). On the other hand, while most Serbian interviewees were living on a small pension, no one received social assistance. All, except one, have never asked for such assistance. Only one urban participant applied for financial support because of disability and long-term disease.

While many had been trying to live within their financial means, debt was a significant issue of concern among Turkish participants. Many had drawn credit in the hope of securing better prospects. For instance, paying for college tuition or contributing to the development of a business for themselves or their children. In both countries, interviewees who were separated from their husbands at a young age, when the children were small, went through deeper economic struggles when bearing the responsibilities of raising children alone. This is especially true for some of the divorcees in the sample. For instance, a Turkish participant who divorced at 18 years, and who had a baby at the time, had to move back to her parents and had to work in two jobs to provide for her child.

3.3.2 Coping with Economic Exclusion After Marriage Disruption

Faced with low income, participants talked about family support, economic resourcefulness, lower levels of consumption, and self-sufficiency all as coping mechanisms.

First, children played an instrumental role in coping with economic and social hardships in both countries in later life. Co-residence was a mechanism for pooling resources. In some cases, financial support provided by children was the main income. “Subsistence was good with my husband. Now I depend on my son” (TM07). Children also facilitated access to services, providing transportation or handling basic administration and form filling, and supporting links to social life such as accompanying their older mothers when shopping, going to weddings and walking. Children were also considered to be a source of participants’ happiness, and thus children’s welfare was also sought. Provision of support by the participants in terms of financing and caring for adult children was also common.

‘If your child is comfortable, you are also comfortable…I drew credit for my son, for my daughter. When there is nothing, if I cannot give, I feel upset’ (TE02).

In Serbia, there were even cases where grandmothers looked after their grandchildren so that their daughters could go abroad and work to provide a better life. Other family members were also mentioned as providing support. “My sister took me in with my little one. We lived in separate houses in a single garden” (TE02). Furthermore, in Serbia, there were cases where older interviewees continue to live with their husband’s parents.

Second, and in terms of economic resourcefulness, most participants who were working before their marital disruption, continued to do so after the disruption had occurred, especially if they were young at that time. Providing for children was a strong incentive to work more. Even some participants in later life continued to demonstrate their economic resourcefulness in mitigating low income, either through income generation activities or subsistence farming (especially in the rural areas). For instance, one participant worked as a live-in helper. Others made tomato paste or knitted clothes.

Third, consuming less, buying only the fundamentals was another dominant coping strategy. Nearly all respondents talk about the need to be prudent.

‘It is all about being prudent. If there is some today, I save the half for tomorrow. I don’t spend all because it is coming. I clean, wash and wear the old. I don’t leave my kids hungry. It is all right if I have 5 cloths instead of 10’ (TE04).

Similarly, lowering expectations and concentrating on non-material aspirations, and abstinence was another coping strategy. “I am old woman, what do I need? Not so much.” (RSV2). In both Serbia and Turkey, the most dominant wish was health, and secondly, for Turkey, peace: “Peace and health. Okay, nothing happens without money, but health is an absolute must” (TE03). Regardless of all the hardships, most participants in both countries were satisfied with their lives. “I am satisfied now, I do just what and how I want to do, to live.” (RST4). As such, contentment surfaced as a coping mechanism connected with abstinence.

Fourth, self-sufficiency was a coping strategy spoken about by older women in both countries. While income was low and repeatedly referred to as insufficient, participants were grateful, especially for the perceived self-sufficiency and independence that their income provided:

‘The income I receive, is it sufficient? No, not at all. But it is better than nothing. I don’t need to go and ask [for] money from my son. I can go and buy needs by myself. I am not dependent on anyone’ (TI13).

Another respondent who received a widowhood allowance stated that “at least I can buy my own medicine” (TE01). Fifth, for most, social life centred around meeting with their neighbours and relatives that lived in their immediate neighbourhoods, a low cost and convenient social activity. Participants living in rural areas or in the outskirts of the cities, gathered in front of their houses during summer. During winter, house visits were more frequent. While some went to weddings/or circumcision feats (Turkey), many refrained going there, either because it was too loud or crowded or due to mobility limitations: “Who wants to see an old woman, they are all young, my time is gone…” (RSV2). Some attended religious gatherings as a source of socialisation.

4 Discussion and Conclusions

Most participants experienced material deprivation and economic exclusion throughout their life, on a continuous or intermittent basis. Coping mechanisms and the extent to which they were employed generally varied. Participants who had previously combined various coping strategies early in life, continued to do so. While they might have needed support from their families, they did not feel needy. However, those who depended on their husbands or families, continued to depend on their children as a resource. In the main, there were few apparent differences between the divorced/separated and widowed participants in terms of coping mechanisms. Many divorcees, most of whom were separated from their husbands at young ages when their children were small, had to shoulder the lone responsibility for their children together with deep financial troubles from an early stage.

In line with the findings of Kok et al. (2018) for those of low socio-economic position, participants in this research demonstrated significant resilience. Among the participants, the most resilient individuals were typically those who had previously been more proactive in coping. This finding supports that of Browne-Yung et al. (2017) who highlighted how coping with adverse life events at various periods of life contributed to resilience. Also, Höltge et al. (2018) provided evidence that moderate adversity experienced in earlier life plays a role in generating a coping capacity for successful ageing.

The findings suggest that materially deprived widowed and separated/divorced older women in Serbia and Turkey employ similar mechanisms to cope with economic exclusion. Some are internal, where individuals exercise the mechanism themselves. Others are external, where individuals receive assistance and mobilise different kinds of resources. While economic resourcefulness, consuming less, and perceived independence are internal, support from family, friends, neighbours and the state are external.

In line with the international literature (Korkmaz 2014; Bennett et al. 2016) the study indicates that the family, especially children, play a central role in coping. Intergenerational support varies in each case and includes financial support (private transfers), accommodation support (through co-residence), transportation and accompaniment with outside tasks. While support with finances and housing is bi-directional, support relating to mobility and domestic chores is primarily given by the children. Friends and neighbours were not mentioned as providing financial support, but they constitute the main pillar of a low-cost social life that participants utilise (Cramm et al. 2012).

Consuming less or living within one’s means is another dominant strategy, one of the most common strategies to mitigate economic difficulties (Fenge et al. 2012; Brünner 2019). Older participants in this study regarded prudence as a virtue and lived accordingly. They “choose” to spend just enough to meet fundamental needs. Within the scope of economic resourcefulness, engaging in income generation activities or semi−/subsistence farming are other strategies and, indeed, were widely employed (Davidova 2011). Consciously adopting low expectations and abstinence were other coping mechanisms.

Moreover, regardless of all the troubles experienced by participants, interviewees expressed satisfaction with life. This confirms the findings of Brünner (2019) for Danish state pensioners and King et al. (2012) for older adults with disabilities. Albeit needing support, perceived independence serves as a strong coping mechanism, and may in some ways be more important than objective assessments (Bennett et al. 2010) in how it contributes to a reservoir of resilience (Becker and Newsom 2005).

Participants in Serbia and Turkey differ in their use of social assistance (public transfers). While all participants are entitled to a state pension in Serbia, this is not the case in Turkey. One of the reasons for this gap is the differences in welfare regimes and their development level during participants’ earlier adulthood. Nevertheless, financial and in-kind social assistance provided by the state, or the municipalities, were typically only a secondary form of coping. However, financial social assistance and pensions did provide a sense of self-sufficiency, independence and dignity, albeit often noted to be generally inadequate. Furthermore, there are differences in coping strategies employed before and after the disruption of marriage ties. Support from wider networks is rare and social assistance is more prevalent, at least in the Turkish case, at later life. This pattern coincides with the expansion of the welfare system in Turkey (Pelek and Polat 2019).

To conclude, this study contributes knowledge to a topic where there is a lack of understanding around the coping mechanisms of widowed and separated/divorced older women experiencing economic exclusion. However, a limitation of the study is that the sample does not include Turkish participants without children. Considering the central role children play in coping strategies, future research should investigate coping mechanisms of older materially deprived women without children in order to develop a more inclusive framework of understanding.

Editors’ Postscript

Please note, like other contributions to this book, this chapter was written before the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. The book’s introductory chapter (Chap. 1) and conclusion (Chap. 34) consider some of the key ways in which the pandemic relates to issues concerning social exclusion and ageing.

References

Barnes, M., Blom, A. G., Cox, K., Lessof, C., & Walker, A. (2006). The social exclusion of older people: Evidence from the first wave of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) (Final report). London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister.

Becker, G., & Newsom, E. (2005). Resilience in the face of serious illness among chronically ill African Americans in later life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60(4), S214–S223.

Bennett, K. M., Reyes-Rodriguez, M. F., Altamar, P., & Soulsby, L. K. (2016). Resilience amongst older Colombians living in poverty: An ecological approach. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 31(4), 385–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-016-9303-3.

Bennett, K. M., Stenhoff, A., Pattinson, J., & Woods, F. (2010). “Well if he could see me now”: The facilitators and barriers to the promotion of instrumental Independence following spousal bereavement. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 53(3), 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634370903562931.

Browne-Yung, K., Walker, R. B., & Luszcz, M. A. (2017). An examination of resilience and coping in the oldest old using life narrative method. The Gerontologist, 57(2), 282–291. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnv137.

Brünner, R. N. (2019). Making ends meet in financial scarcity in old age. International Journal of Ageing and Later Life, 13(1), 35–62. https://doi.org/10.3384/ijal.1652-8670.18391.

Calasanti, T. (2010). Gender and ageing in the context of globalization. In D. Dannefer & C. Philipson (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social gerontology (pp. 137–149). Los Angeles: SAGE.

Cramm, J. M., Van Dijk, H. M., & Nieboer, A. P. (2012). The importance of neighborhood social cohesion and social capital for the well being of older adults in the community. The Gerontologist, 53(1), 142–152.

Davidova, S. (2011). Semi-subsistence farming: An elusive concept posing thorny policy questions. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 62(3), 503–524.

Eurostat. (2019). Glossary: Material deprivation. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Material_deprivation. Accessed 10 Feb 2019.

Fenge, L. A., Hean, S., Worswick, L., Wilkinson, C., Fearnley, S., & Ersser, S. (2012). The impact of the economic recession on well-being and quality of life of older people. Health & Social Care in the Community, 20(6), 617–624.

Ferra, E. L. (2010). Family and kinship ties in development. In J.-P. Platteau & R. Peccoud (Eds.), Culture, institutions, and development: New insights into an old debate (pp. 107–124). London: Routledge.

Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 117–125.

Georgas, J. (2006). Families and family change). In J. Georgas, J. W. Berry, F. J. Van de Vijver, Ç. Kagitçibasi, & Y. H. Poortinga (Eds.), Families across cultures: A 30-nation psychological study (pp. 3–50). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Höltge, J., Mc Gee, S. L., Maercker, A., & Thoma, M. V. (2018). A salutogenic perspective on adverse experiences. European Journal of Health Psychology, 25, 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1027/2512-8442/a000011.

King, J., Yourman, L., Ahalt, C., Eng, C., Knight, S. J., Pérez-Stable, E. J., et al. (2012). Quality of life in late-life disability: “I don’t feel bitter because I am in a wheelchair”. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(3), 569–576.

Kneale, D. (2012). Is social exclusion still important for older people? (International longevity centre report). London: International Longevity Centre.

Kok, A. A. L., van Nes, F., Deeg, D. J. H., Widdershoven, G., & Huisman, M. (2018). “Tough times have become good times”: Resilience in older adults with a low socioeconomic position. The Gerontologist, 58(5), 843–852. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny007.

Korkmaz, N. K. (2014). Old age, family and the transfer of the capitals in the context of Pierre Bourdieu-Examples from two fieldworks in Turkey. In A. Klein, A. M. Chavez Hernandez, L. F. Macias Garcia, & C. Rea (Eds.), Identidades, vínculos y transmisión generaciona (pp. 115–126). Boenos Aires: Manantial.

Levitas, R., Pantazis, C., Fahmy, E., Gordon, D., Lloyd-Reichling, E., & Patsios, D. (2007). The multi-dimensional analysis of social exclusion. Bristol: Bristol Institute for Public Affairs, University of Bristol.

Myck, M., Ogg, J., Aigner-Walder, B., Kareholt, I., Kostakis, I., Motel-Klingebiel, et al. (2017). ‘Economic aspects of old age exclusion: A scoping report’ knowledge synthesis series. ROSEnet Cost Action (CA15122) Reducing Old-Age Social Exclusion: Collaborations in Research & Policy.

Pelek, S., & Polat, S. (2019). Exploring inter-household transfers: An assessment using panel data from Turkey. Istanbul: Galatasaray University Economic Research Center 19–01.

Phillipson, C., & Scharf, T. (2004). The impact of government policy on social exclusion among older people. London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister.

Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M., & Ormston, R. (2013). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London: SAGE.

Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2012). Qualitative interviewing (3rd ed.): The art of hearing data. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226651.

Sataric, N., Milićević-Kalašić, A., & Ignjatovic, T. (2013). Deprived of rights out of ignorance report on monitoring of the human rights of older people in residential care in Serbia. Belgrade: Inpress.

Scharf, T. (2015). Between inclusion and exclusion in later life. In G. Carney, K. Walsh, & A. Ní Léime (Eds.), Ageing through austerity: Critical perspectives from Ireland (pp. 113–130). Bristol: Policy Press.

Sen, A. (2000). Social exclusion: Concept, application, and scrutiny. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

Sheppard, M. (2012). Social work and social exclusion: The idea of practice. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Thoma, M. V., & Mc Gee, S. L. (2019). Successful aging in individuals from less advantaged, marginalized, and stigmatized backgrounds. Clinical Psychology in Europe, 1(3), e32578. https://doi.org/10.32872/cpe.v1i3.32578.

UNECE. (2016). The active ageing index pilot studies for Turkey and Serbia. Available at: https://statswiki.unece.org/download/attachments/76287849/Pilot%20study%20for%20Serbia%20and%20Turkey%20final.pdf?version=1&modificationDate=1473167139525&api=v2. Accessed 20 Sept 2019.

United Nations, D. o. E. a. S. A., Population Division. (2019). World population ageing 2019: Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/430).

Van Kessel, G. (2013). The ability of older people to overcome adversity: A review of the resilience concept. Geriatric Nursing, 34(2), 122–127.

Wagner, M., & Mulder, C. H. (2015). Spatial mobility, family dynamics, and housing transitions. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 67(1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-015-0327-4.

Walsh, K., Scharf, T., & Keating, N. (2017). Social exclusion of older persons: A scoping review and conceptual framework (journal article). European Journal of Ageing, 14(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-016-0398-8.

Whitley, E., Benzeval, M., & Popham, F. (2018). Associations of successful aging with socioeconomic position across the life-course: The West of Scotland Twenty-07 prospective cohort study. Journal of Aging and Health, 30(1), 52–74.

Wiles, J. L., Wild, K., Kerse, N., & Allen, R. E. S. (2012). Resilience from the point of view of older people: ‘There’s still life beyond a funny knee’. Social Science & Medicine, 74(3), 416–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Barlin, H., Vojvodic, K., Mercan, M.A., Milicevic-Kalasic, A. (2021). Coping Mechanisms of Divorced and Widowed Older Women to Mitigate Economic Exclusion: A Qualitative Study in Turkey and Serbia. In: Walsh, K., Scharf, T., Van Regenmortel, S., Wanka, A. (eds) Social Exclusion in Later Life. International Perspectives on Aging, vol 28. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51406-8_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51406-8_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-51405-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-51406-8

eBook Packages: HistoryHistory (R0)