Abstract

Throughout the lifespan, unemployment has severe consequences in terms of economic exclusion, and overall social exclusion, but is compounded in older age. Within the EU, a growing number of older adults (50+) are affected by joblessness. Job loss at a later stage in a professional career may determine an early and permanent exit from the labour market with significant psychosocial consequences. Herein lies the age-specific risk for older unemployed adults: once becoming unemployed they are at greater risk at staying unemployed. As a result, older unemployed people may face income cuts, deprivation of a central adulthood role and their mental and physical health may suffer. In this chapter, we draw attention to the latent functions of work, and the psychosocial consequences of job loss in later life. Applying a life-course perspective, the aim of this chapter is to explore how job loss can be framed as a form of acute economic exclusion, and how this exclusion can have significant implications for poor mental health. In a context of rising retirement ages, and the lack of preparedness of the labour market to deal with an ageing workforce, it is essential to understand these dynamics to guide policy development.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In 2018, a record number of 71,338 people between the ages of 50 and 64 years old were unemployed in Europe (OECD 2018). The number of people aged 65 years or over in the world is forecast to increase by 46% between 2017 and 2030, outnumbering younger people in a huge social transformation (ILOSTAT 2019). Thus, the number of people aged 50 years and over in the labour force will increase significantly. Furthermore, the political shift towards extending working lives, by increasing statutory retirement age, makes early retirement financially less sustainable. This results in more older workers registering as unemployed when made redundant. The implications of these circumstances for experiences of economic exclusion have the potential to be severe. Despite this and the growing number of older people affected by unemployment, there is a marked lack of unemployment policies targeting late-career unemployed. There is also a general lack of research exploring how late career job loss may generate severe forms of economic exclusion in later life, with implications for material and other forms of economic outcomes. Although significant consequences for psychosocial well-being have been documented for other groups of unemployed people (McKee-Ryan et al. 2005; Paul and Moser 2009; Griep et al. 2015), there has been little consideration of these impacts for older workers.

In this chapter, we draw attention to the latent functions of work and the psychosocial consequences of job loss in later life. Applying a life-course perspective, the aim of this chapter is to explore how job loss can be framed as a form of acute economic exclusion, and how this exclusion can have significant implications for poor mental health. We start by considering ageing and work and positioning the experience of work within the older adult life course. We provide a brief look at ageing in general, and the phase of middle adulthood in particular, before turning to the specifics of the older adult worker. We then look at the latent functions of work, which can be closely linked to the framework of old-age exclusion (Walsh et al. 2017; Walsh 2019). We then turn to the economic and psychosocial consequences of unemployment. As the German novelist Thomas Mann (2019) observed “Work is hard, is often a bleak and tedious prodding; but not working – that is hell”. Focusing on the experiences of older unemployed persons in Luxembourg, we will present selected survey findings around the subjective experience of unemployment and coping processes, and their relationship with psychosocial well-being. We present this analysis in an effort to inform policy development for assisting older adults in dealing with the economic and psychosocial consequences of unemployment.

2 Ageing and Work

We are all ageing. To live is to grow older. As we move into adulthood, two aspects dominate – intimacy – forming close relationships, and generativity – being productive for and supporting future generations (Erikson 1963). Various terms have been suggested to describe these aspects including affiliation and achievement, attachment and productivity, commitment and competence. As observed by Freud (1935), adulthood is about love and work. A healthy adult is one who can love and work. For many adults, the answer to the question “Who are you?” depends on the answer to “What do you do?” Work can provide us with a sense of identity and opportunities for accomplishment (Myers 2006). Challenging and interesting positions enhance people’s happiness. Research has shown that it is not the occupational role per se, but it is the quality of experience in the respective roles that mattered and affected well-being (Baruch and Barnett 1986). Happiness is about finding work that fits your interest and provides you with a sense of competence. Employment marks the transition into adulthood. Failure to make this transition into work and to establish an occupational identity can be accompanied by increased stress levels (Donovan and Oddy 1982; Tiggemann and Winefield 1984). The phase of middle adulthood is the phase of quiet transitions and has been characterised as an “in-between state.” At 40 years plus, one is neither young nor old and the generational structure is changing (Perrig-Chiello and Höpflinger 2001; Höpflinger and Perrig-Chiello 2009). Children are in the process of leaving or having left home and individuals’ parents are getting older and needing more care, requiring an intergenerational role reversal. In addition to this “in-between” positioning, this phase in life is accompanied by commitment and closure, as substantial decisions have been taken in the professional and private domain. Even though changes are still possible, these are increasingly effortful and complicated. It is a time of taking stock about goals accomplished – and a realisation that opportunities for professional change/mobility or future chances for professional re-orientation are reducing.

In that sense, ageing is the simultaneous accumulation of achievements and alternatives not taken (Perrig-Chiello and Höpflinger 2001). Paul and Moser (2009) noted that it is often assumed that this middle-aged group would be psychologically hardest hit by unemployment as this group often has family responsibilities, greater dependence on financial income and strong career commitment. However, in a meta-analysis these authors showed a curvilinear relationship between age, psychological stress and unemployment, with young unemployed and older unemployed nearing retirement showing the highest stress levels. The authors expressed surprise at this finding and commented that “studies with older unemployed workers are also rare, although most industrialised societies experience demographic changes that will lead to a higher proportion of elder persons in the labour market in the near future” (Paul and Moser 2009, p. 280).

Successful ageing means selective optimisation and compensation to maximise the use and mobilisation of available resources (Baltes et al. 1992). Yet, with increasing age, the range of options diminishes. Across the lifespan, the overall aim is thus to solidify gains and to minimise losses. As explained in the life-cycle theory of consumption (Modigliani and Brumberg 1954) people plan their lifetime economic activity. If unemployment hits in old-age – there may not be a chance to recover the losses. Older persons are not at greater risk to become unemployed – the age-specific risk is to stay unemployed (Brussig et al. 2006). As such, the risk of being long-term unemployed and never regaining access to the labour market increases with age.

2.1 The Meaning of Work

The increased stress levels among the older unemployed may be explained by considering the meaning of work. Marie Jahoda (1981, 1983, 1997) looked beyond the obvious economic consequences of (un-) employment and explored the psychological meaning of employment and unemployment. Jahoda developed the model of manifest and latent functions of employment. The manifest function of work is earning money – which maps to the domain of material and financial resources in the framework on old-age exclusion (Walsh et al. 2017). Yet work also fulfils latent functions and these include (a) providing a clear time structure, (b) an activity, (c) social status, (d) social contact beyond the nuclear family and (e) participation in a collective purpose, allowing meaningful societal engagement (Jahoda 1997). It can be argued that these latent functions mirror elements of other domains of social exclusion frameworks, namely social relations, socio-cultural factors, neighbourhood and community and civic participation. These latent functions of work satisfy important human needs with employment deprivation having psychosocial consequences.

If people are deprived access to these latent functions, their mental health will suffer. Jahoda’s model has found empirical support (e.g. Paul and Batinic 2010; Selenko et al. 2011). However, Jahoda’s model has also been criticised for placing not enough weight on the manifest factors (Fryer 1986). Paul and Moser (2006) suggest the incongruence hypothesis. They argue that a lack of fit between aspirations in terms of values and life goals and the current state of employment is the main source of stress. However, despite these differences, what these models have in common is that they link economic, social and psychological functions relating to the meaning of work.

2.2 Economic Consequences of Unemployment at 50+

In western capitalist societies, paid work is still the main source of income for most people and it allows access to vital material resources and to the “consumers’ society’. Even in more generous welfare states that provide higher unemployment benefits, these are always a percentage of previous salaries and for a limited period. As noted by Brand (2015), job loss is an involuntary disruptive life event with far-reaching impact on workers’ life trajectories. She clarifies the differences between job loss and unemployment. Whereas job loss is a discrete event, unemployment is a transitional state with a great deal of heterogeneity with respect to instigation and duration. Involuntary job loss may also indicate job separation as a result of health conditions – which becomes increasingly likely with advancing age. Job separation for health reasons may be worker initiated but can nevertheless be considered involuntary (Brand 2015). Ultimately, unemployment, and particularly long-term unemployment, represents financial deprivation and material ill-being [see Sumil-Laanemaa et al. this section]. Older unemployed adults can experience a longer duration before reemployment, with post-displacement jobs then tending to be of a shorter duration (Chan and Stevens 2001), to pay less than the lost job, and to be of lower quality (Samorodov 1999). Unemployment also diminishes income flows and represents a toll on retirement pensions. This heightens economic exclusion into older-ages (Chan and Stevens 1999; Arent and Nagl 2010; Myck et al. 2017). Commenting on the economic effects of job loss, Brand (2015) noted that the cumulative lifetime earning loss is estimated to be roughly 20%, with wage-scarring observed as long as 20 years post displacement. As noted above, older workers are at greater risk to stay unemployed and may therefore not have the opportunity to make up for losses. Thus, the economic consequences for older unemployed are potentially even more severe.

2.3 Psychosocial Consequences of Unemployment at 50+

A large body of research has focused on the relationship between unemployment and psychological well-being (e.g. McKee-Ryan et al. 2005; Paul and Moser 2009; Brand 2015). Paul and Moser (2009) compared mental health of employed and unemployed persons for the general population. Their study showed that 16% of the employed and 34% of the unemployed persons suffered from mental health problems. Thus, the unemployed have twice the risk of suffering from mental illness – unemployment having the potential to be a serious threat to public health. Paul and Moser’s (2009) analyses also showed that the young and older unemployed are at particular risk in terms of mental health. Thus for the older-age group involuntary unemployment not only represents labour market exclusion or higher exposure to precariousness and economic deprivation, they are also more affected by psychosocial-related consequences as is confirmed by specific research on older unemployed workers (e.g. Chu et al. 2016). Later life unemployment may therefore threaten participation of older adults in the labour market as well as the realisation of ones’ potential. Drawing on literature on the more general area of health and employment, unemployment is a risk factor for detriments in mental and physical health, physical disability and difficulties in performing basic activities of daily living (Gallo et al. 2009; Chu et al. 2016). This has the potential to widen the already steep health inequality at midlife and increase the risk of economic and social exclusion in later life. The onset of several illnesses has been attributed to experiences of job loss and older unemployed have a higher risk of physical disability (Gallo et al. 2009). Chu et al.’s (2016) study evaluated whether late-career unemployment is associated with increased all-cause mortality, functional disability, and depression among older adults in Taiwan. Their findings indicate that late-career unemployment increases the risks of future mortality and disability. Despite affecting a large number of people and its consequences being so severe, the literature that looks at the lived experience of unemployment in late career in relation to exclusion is not abundant.

One of the few in-depth studies focusing on psychosocial vulnerabilities of older adults following unemployment was conducted by Hansson et al. (1990). The aim of this study among 82 older unemployed adults was to gain a better understanding of the psychosocial consequences of unemployment – with a view to developing targeted unemployment counselling programmes for older adults. Their data suggested that support for older unemployed should attempt to differentiate between clients with different needs and different profiles of personal and social competence. Their findings point to the diversity of older unemployed. The authors observed that professional seniority does not offer protection for older workers in times of crisis. On the contrary – older workers in senior positions were found to have to compete with younger workers who were sometimes more mobile, whose education was more recent and possibly more extensive, and who often had more transferable skills. In addition, older workers were more likely to need training in interview skills and job-hunting strategies, given their time spent in stable employment. Again, older adults were found to be in danger of experiencing prolonged unemployment and often were found to have dropped out of the job market altogether. Prolonged unemployment also contributed to the decision to accept early retirement, even at reduced benefit.

Therefore, unemployment in late career may be the greatest threat to one’s security and independence because of the risk of permanent exclusion from the labour market. The severity of health and psychological consequences were related to what a person lost when losing their job. Older workers, who had been loyal and productive for many years and committed more of their identity to work, were psychologically more affected by the unemployment. This is referred to as work-role centrality in McKee-Ryan and Kinicki’s (2002) life facet model of coping with job loss. The authors explain the process of reacting to job loss in a coping – stress framework. Based on this model, McKee-Ryan et al. (2005) developed a taxonomy for their meta-analytic study on well-being during unemployment. Contributing elements to psychological and physical well-being following job loss include the aforementioned: (a) work-role centrality, that is the general importance of the work role to an individual’s sense of self; (b) coping resources; (c) cognitive appraisal including attribution style; (d) coping strategies, i.e. the cognitive and behavioural efforts linked to managing the situation; and (e) human capital and demographics, i.e. education, ability and educational status.

To delve further into first-hand experiences of these impacts, in the next section we will consider a recent empirical study concerning coping strategies, well-being and job loss conducted in Luxembourg.

3 Coping Strategies and Well-being Among Older Unemployed in Luxembourg

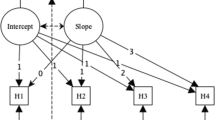

In accordance with the life facet model of coping with job loss (McKee-Ryan and Kinicki’s 2002), we investigated the role of cognitive appraisal, coping strategies and coping resources in subjective well-being of older unemployed. People differ in how they interpret job loss. How responsibility for job loss is assigned and interpreted, or cognitively appraised, is relevant to well-being in unemployment (McKee-Ryan et al. 2005). Coping strategies are also associated with increased psychological health during unemployment (Kanfer et al. 2001). Coping resources such as social support and personal traits (i.e. self-efficacy or emotional stability) also contribute to psychological well-being (McKee-Ryan and Kinicki 2002).

3.1 Methodology

3.1.1 Participants

Sixty-seven older unemployed individuals participated in this quantitative study in Luxembourg and completed a paper-based questionnaire. They were recruited at advisory and training centres for unemployed persons. Women were over-represented in this sample with n = 54 (80.6%). The average age was 52.65 (SD = 3.86, range = 46–61). The educational level was reasonably high with 34% of the sample holding a university degree and 21% holding the highest school leaving qualification (13 years of secondary education). Sixteen per cent held a professional qualification and 15% completed basic education (9 years of education) whilst 13% indicated other. Health restrictions were indicated by 28% of respondents. About 30% lived alone. A further 30% lived with their partner and their children: 20% lived with just their partner and 16% identified themselves as single mothers.

The (un-)employment history of respondents is summarised in Table 4.1 and illustrates a sample with a broad range of (un-)employment experiences. Participants with health restrictions are concentrated in the longer-term (>12 months) unemployment group.

3.2 Measures

For cognitive appraisal processes, respondents had to rate to what extent a range of factors contributed to their job loss on a scale from one (not at all) to five (a lot). As shown in Table 4.2, some of these factors are external to the person, such as a crisis within the company or the economic climate. If a person associated their job loss with such an external event, we classified this as an external attribution (E). Other factors were associated directly with the person, which we classified as internal (I). While some of these internal factors could be potentially controlled by a person (i.e. engagement or skills) others, such as age or illness, were outside their control.

We also developed a series of items assessing coping strategies and resources. The items and domains are listed in Table 4.3. For proactive coping, the domains include persistence and flexibility of goal adjustment. Regarding coping resources, we included external and family support. In terms of personal resources, we included self-efficacy and hope. Since we focus on older unemployed persons, we also asked specifically about age as a barrier to regaining employment. Participants rated these items on a scale from one (does not apply at all) to four (totally applies).

Subjective well-being was assessed using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS, Diener et al. 1985, Diener 2006). The scale consists of five items, which are assessed on a seven-point Likert Scale. The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the SWLS scale was 0.80.

3.3 Results

Over half (55%) of the respondents attributed their unemployment, at least in part, to their age, but the extent of this designation was varied. While 45% indicated that age did not play a role in becoming unemployed, 9% indicated that age played a large role, 15% indicated it played a role, and a further 15% thought that age played a small role. For all other categories, the response pattern was different – with each factor either playing either an important role or none. Thus, when rating factors contributing to unemployment, gradations were hardly used, with the exception of age. With reference to Table 4.2, external attribution for job loss dominates, apart from age (2nd place) and illness. These latter factors are associated with the individual but are outside respondents’ control.

Descriptive statistics for the items relating to the subjective experience of unemployment and coping strategies are presented in Table 4.3 and show means above the scale midpoint for all domains. There are no gender differences.

A comparison of groups according to length of unemployment (n = 24 < = 3 months; n = 14, 4–11 months; n = 29 > = 12 months) showed no significant differences for these items or domains with one exception: more recent unemployed had significantly lower mean scores for age as a barrier than the other two groups: F(2,64) = 3.2 p < 0.05 (M<=3 m = 2.79 SD = 0.85; M4-11m = 3.25, SD = 0.70; M> = 12m = 3.26, SD = 0.59).

For the SWLS scale, the mean response at M = 4.01 SD = 1.25 was close to the scale midpoint of 4. Items with lower mean score were The conditions of my life are excellent (M = 3.66, SD = 1.68) and If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing (M = 3.74, SD = 1.9).

The relationship between well-being and the various domains pertaining to coping with unemployment is presented in Table 4.4.

Family support and hope are significantly correlated with well-being. The length of unemployment, as a situational factor, is negatively correlated with SWLS r = − 0.42**. To assess how well family support and length of unemployment predict well-being, a hierarchical multiple regression was performed, controlling for health restrictions. These were entered in Step 1 explaining 6% of the variance in SWLS scores. After entering length of unemployment and family support into the model, the total variance of the model was 26%, F(3,61) = 8.33, p < 0.001. These two variables explained 22% of the variance with an R squared change = 0.22, F change (2,61) = 9.33, p < 0.001. In the model both measures were statistically significant with length of unemployment recording a slightly higher beta value (beta = −2.87, p < 0.01) than family support (beta = 2.77, p < 0.01).

4 Discussion

This chapter set out to explore how job loss can be framed as a form of acute economic exclusion, and how this exclusion can have significant implications for poor mental health. As repeatedly noted, the age-specific risk of job loss, and a significant detractor of economic inclusion, is prolonged unemployment, or never gaining access to the labour market again, with potentially severe economic and psychosocial consequences. With increasing age, the range of income generation options diminishes, and the recovery of financial losses incurred through unemployment is increasingly difficult or even impossible. Not surprisingly, the meta-analytic study by Paul and Moser (2009) showed that young and older unemployed nearing retirement showed the highest stress levels. Older unemployed are at higher risk of permanent exclusion from the job market, being deprived of both, the manifest and latent functions of work. What is surprising is the relative scarcity of empirical studies on psychosocial consequences of job loss in later life – given the dramatic demographic change we face, with older people forecast to outnumber young people in a social transformation (ILOSTAT 2019). The empirical study conducted in Luxembourg is a first step to address this research gap.

In terms of cognitive appraisal of the job loss, it is important to point out that over half of the Luxembourg participants attributed their job loss, at least in part, to their age. Age was also seen as a barrier to regaining employment, with the effect being stronger for the longer-term unemployed workers. Our respondents feel discriminated against because of their age – and research evidence seems to confirm this assessment as studies have shown that prolonged or permanent unemployment is an age-specific risk (Brussig et al. 2006). The onset of illness is another risk factor whose relevance appears to increase with age and persons with health restrictions were indeed overrepresented in the long-term unemployed group in our sample. Furthermore, 28.4% of our respondents indicated that sickness or health related problems played a role in becoming unemployed.

The respondents in our study were, on average, very proactive in trying to get new employment – willing to retrain and even prepared to accept a job at lower wages. They were also optimistic in regaining employment – even though that optimism fades with increasing length of unemployment. This positive outlook in our sample may be a function of the flourishing Luxembourg job market, the high educational standing of the sample and a generous unemployment benefit system – factors that have been shown to buffer the negative effects of unemployment (Griep et al. 2015). The overall SWLS score at the midpoint of the scale is typical in economically developed nations (Diener 2006). The majority of people are generally satisfied, but have some areas where they would like improvements. Lower scores were obtained for the conditions of life item and participants would change things, if they could lead their lives over again. Not surprisingly, length of unemployment has a detrimental effect on subjective well-being. We also observed a buffering effect of family support.

Our sample of older unemployed is highly heterogeneous with different employment trajectories until the point of job loss. A glance at Table 4.1 depicting the employment history for our participants illustrates the very different (un-) employment trajectories that our participants have experienced. Consequently, assistance efforts to gain reemployment need to take this diversity and the different sets of coping resources and coping strategies into consideration. Even though we could not explore the dimension in depth, there were some precarious cases within our sample who would require a range of support measures – from building up relational capabilities to providing language training to specific skills training courses. Others may just need a refresher course in interview skills. Special support needs to be given to those with high work-role centrality as work as provider for meaning and fulfilment no longer exists – and this loss has been linked to lower psychological well-being (McKee-Ryan et al. 2005). Building on the beneficial role of family support, as indicated by our findings, assistance efforts might involve family members. Therefore, a “one-size-fits-all” approach is not appropriate for the 50 + unemployed group, who have less time remaining in their occupational career in which to recover from the consequences of the prolonged job loss, and are at heightened risk of economic exclusion.

5 Conclusion

There are limitations to this empirical research. First, the small sample size and the non-representative composition of the sample must be mentioned. The research is also correlational – so no conclusions about causality can be drawn. Some measures have been developed specifically for this study and need to be validated. We also only focused on subjective well-being and did not include specific measures to assess mental and physical health. However, there are surprisingly few studies focusing on the psychosocial consequences and lived experiences of older unemployed. The present study was a first attempt to address this imbalance. Ultimately, given the potentially severe consequences of late career unemployment (see Chu et al. 2016) and the rising number of older workers, dedicated research programmes that explore the diverse circumstances and experiences of this group are urgently needed.

Editors’ Postscript

Please note, like other contributions to this book, this chapter was written before the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. The book’s introductory chapter (Chap. 1) and conclusion (Chap. 34) consider some of the key ways in which the pandemic relates to issues concerning social exclusion and ageing.

References

Arent, S., & Nagl, W. (2010). A fragile pillar: Statutory pensions and the risk of old-age poverty in Germany. FinanzArchiv: Public Finance Analysis, 66(4), 419–441.

Baltes, P. B., Smith, J., & Staudinger, U. M. (1992). Wisdom and successful aging. In T. B. Sonderegger (Ed.), The Nebraska symposium on motivation: Vol. 39. The psychology of aging (pp. 123–167). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Baruch, G. K., & Barnett, R. (1986). Role quality, multiple role involvement, and psychological well-being in midlife women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 578–585.

Brand, J. E. (2015). The far-reaching impact of job loss and unemployment. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043237.

Brussig, M., Knuth, M., & Schweer, O. (2006). Arbeitsmarktpolitik für ältere Arbeitslose Erfahrungen mit „Entgeltsicherung“ und „Beitragsbonus“. IAT Report 02, Institut Arbeit und Technick, Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie.

Chan, S., & Stevens, A. H. (1999). Employment and retirement following a late-career job loss. American Economic Review, 89(2), 211–216.

Chan, S., & Stevens, A. H. (2001). Job loss and employment patterns of older workers. Journal of Labor Economics, 19(2), 484–521.

Chu, W. M., Liao, W. C., Li, C. R., Lee, S. H., Tang, Y. J., Ho, H. E., & Lee, M. C. (2016). Late-career unemployment and all-cause mortality, functional disability and depression among the older adults in Taiwan: A 12-year population-based cohort study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 65, 192–198.

Diener, E. (2006). Understanding scores on the satisfaction with life scale. http://labs.psychology.illinois.edu. Accessed 10 Oct 2019.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Donovan, A., & Oddy, M. (1982). Psychological aspects of unemployment: An investigation into the emotional and social adjustment of school leavers. Journal of Adolescence, 5, 15–30.

Erikson, E. (1963). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Freud, S. (1935, reprinted 1960). A general introduction to psychoanalysis. New York: Washington Square Press.

Fryer, D. (1986). Employment deprivation and personal agency during unemployment: A critical discussion of Jahoda’s explanation of the psychological effects of unemployment. Social Behaviour, 1, 3–23.

Gallo, W. T., Brand, J. E., Teng, H. M., Leo-Summers, L., & Byers, A. L. (2009). Differential impact of involuntary job loss on physical disability among older workers: Does predisposition matter? Research on Aging, 31(3), 345–360.

Griep, Y., Hyde, M., Vantilborgh, T., Bidee, J., De Witte, H., & Pepermans, R. (2015). Voluntary work and the relationship with unemployment, health, and well-being: A two-year follow-up study contrasting a materialistic and psychosocial pathway perspective. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(2), 190–204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038342.

Hansson, R. O., Briggs, S. R., & Rule, B. L. (1990). Old age and unemployment: Predictors of perceived control, depression, and loneliness. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 9(2), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/073346489000900209.

Höpflinger, F. & Perrig-Chiello, P. (2009). Hauptergebnisse eines empirischen Projekts zum Wandel des mittleren Erwachsenenalters – in Thesenform. Retrieved from: http://www.hoepflinger.com/fhtop/fhmidage1.html. Accessed 9 Dec 2019.

ILOSTAT Labour Force Statistics. (2019). Older workers are most discouraged in these countries. https://ilostat.ilo.org/2019/10/01/older-workers-are-most-discouraged-in-these-countries/ Accessed 8 Dec 2019.

Jahoda, M. (1981). Work, employment, and unemployment: Values, theories, and approaches in social research. American Psychologist, 36(2), 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.2.184.

Jahoda, M. (1983). Wieviel Arbeit braucht der Mensch? Arbeit und Arbeitslosigkeit im 20. Weinheim: Jahrhundert.

Jahoda, M. (1997). Manifest and latent functions. In Nicholson, N. (Hrsg.), The Blackwell encyclopedic dictionary of organizational psychology (pp. 317–318). Oxford.

Kanfer, R., Wanberg, C. R., & Kantrowitz, T. M. (2001). Job search and employment: A personality-motivational analysis and meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 837–855.

Mann, T. (2019). https://www.zitate.de/autor/Mann%2C+Thomas?page=2. Accessed 8 Dec 2019.

McKee-Ryan, F. M., & Kinicki, A. J. (2002). Coping with job loss: A life-facet model. International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 17, 1–29.

McKee-Ryan, F. M., Song, Z., Wanberg, C. R., & Kinicki, A. J. (2005). Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 53–76.

Modigliani, F., & Brumberg, R. (1954). Utility analysis and the consumption function: An interpretation of cross-section data. Post-Keynesian Economics, 1, 338–436.

Myers, D. (2006). Psychology (8th ed.). New York: Worth.

Myck, M., Ogg, J., Aigner-Walder, B., Kåreholt, I., Motel-Klingebiel, A., Marbán-Flores, R., & Thelin, A. (2017). Economic Aspects of old age exclusion: a scoping report. ROSEnet Economic Working Group Action, Knowledge Synthesis Series: No 1. CA 15122 Reducing Old-Age Exclusion: Collaborations in Research and Policy.

OECD. (2018). Labour Force Statistics (LFS). Retrieved from: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=LFS_SEXAGE_I_R. Accessed 3 Dec 2019.

Paul, K. I., & Batinic, B. (2010): The need for work: Jahoda’s latent functions of employment in a representative sample of the German population. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(1), 45–64.

Paul, K. I., & Moser, K. (2006). Incongruence as an explanation for the negative mental health effects of unemployment: Meta‐analytic evidence. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79(4), 595–621.

Paul, K. I., & Moser, K. (2009). Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(3), 264–282.

Perrig-Chiello, P., & Höpflinger, F. (2001). Zwischen den Generationen. Frauen und Männer im mittleren Lebensalter. Zürich: Seismo-Verlag.

Samorodov, A. (1999). Ageing and labour markets for older workers. Geneva: Employment and Training Department, International Labour Office.

Selenko, E., Batinic, B., & Paul, K. I. (2011). Does latent deprivation lead to psychological distress? Investigating Jahoda’s model in a four-wave study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(4), 723–740.

Tiggemann, M., & Winefield, A. H. (1984). The effects of unemployment on the mood, self-esteem, locus of control, and depressive affect of school-leavers. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 57(1), 33–42.

Walsh, K. (2019). Reducing old-age social exclusion in Europe. Presentation at 5th ROSEnet European Policy Seminar on 11.01.2019 in Paris, France.

Walsh, K., Scharf, T., & Keating, N. (2017). Social exclusion of older persons: A scoping review and conceptual framework. European Journal of Ageing, 14(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-016-0398-8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Murdock, E., Filbig, M., Borges Neves, R. (2021). Unemployment at 50+: Economic and Psychosocial Consequences. In: Walsh, K., Scharf, T., Van Regenmortel, S., Wanka, A. (eds) Social Exclusion in Later Life. International Perspectives on Aging, vol 28. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51406-8_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51406-8_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-51405-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-51406-8

eBook Packages: HistoryHistory (R0)