Abstract

We contribute to the discussion on social exclusion interrelationships by examining the relationship between material conditions and loneliness, as one potential marker of connections between the social and economic domain. Our analysis focuses on a sample of individuals aged 50+ in the Survey of Health Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). In its 5th wave, the survey was extended to include specific items related to economic and social deprivation. We use this extended information on material conditions and examine how it correlates with the level and dynamics of a composite loneliness measure at the time of wave 5 and between wave 5 and 6 of the survey (undertaken in 2013 and 2015, respectively). In order to isolate the effect of material deprivation on loneliness, regression analyses include an extensive set of control variables. The analyses show a strong and significant relationship between material deprivation, and both the level of loneliness and deterioration in the loneliness status.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This chapter focuses on two domains of social exclusion: economic exclusion – in the form of material resources – and exclusion from social relations – in the form of loneliness. Usually, material resources are measured via indicators related to income or wealth, while social relations are measured via indicators of social contacts and social participation. Here we consider a more nuanced approach, on the one hand taking a comprehensive measure of material deprivation [also see Ogg and Myck, and Sumil-Laanemaa et al. this volume] and on the other using loneliness as a reflection, or outcome of exclusion from social relations (Burholt et al. 2019; see also Burholt and Aartsen, and Morgan et al. this volume). Based on longitudinal data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), the aim of this chapter is to examine the dynamics of loneliness and to investigate the causal relationship between material resources and loneliness. In doing this, we hope to better illuminate some of the interconnections between social and economic domains of exclusion. Despite the growing body of work on exploring links between economic and social factors in later life, we still lack the scientific insights to understand how outcomes and processes across these domains intersect in the exclusion of older adults.

The chapter starts with definitions of material deprivation and loneliness, and a review of previous research on the relationship between them and with other risk factors that are relevant to understand this relationship. The following sections present data, methods and results. A discussion of the findings completes the chapter.

2 Material Deprivation and Loneliness in Ageing Populations

Material deprivation occurs when an individual or household is unable to (rather than chooses not to) afford a number of goods and services, e.g. unexpected expenses and payment arrears, adequate heating or a washing machine (Eurostat 2018). This concept differs from the measurement of poverty defined on the basis of personal or household income most often used in relation to national medians (EurostatFootnote 1). While current income as a measure of resources has its merits and has been a common reference for numerous studies, there is growing literature which shows that it may fail to accurately reflect the complexity of material conditions. From this perspective the important advantage of material deprivation measures which we use in this chapter, is that they reflect the combination of material resources and material needs which may be of high relevance for understanding the conditions in old-age.

Loneliness is understood to mean:

‘the negative outcome of a cognitive evaluation of a discrepancy between (the quality and quantity of) existing relationships and relationship standards’ (de Jong Gierveld et al. 2006, p. 495).

Recently, Tesch-Römer and Huxhold (2019) noted that loneliness is not necessarily a consequence of growing old, but depends on specific risk factors such as financial and material resources, and Fokkema et al. (2012) have underscored that “wealth and health are conditions for engaging in satisfying personal relationships and thus for the prevention and alleviation of loneliness” (p. 221). The literature on loneliness employs several measures to locate people’s position within society, for example, demonstrating a relationship between loneliness and socio-economic position (Fokkema et al. 2012), income (De Jong Gierveld and Tesch-Römer 2012), poverty (Haushofer 2013), and low education and material deprivation (Gibney et al. 2019). Franzese (2015) found that material deprivation was more strongly correlated with health outcomes (especially mental health, including loneliness) than with income poverty.

Previous research also points to the importance of deprivation at neighbourhood level. Scharf et al. (2005) identified much higher rates of severe loneliness in deprived urban neighbourhoods than other English loneliness studies. A later comparison between deprived neighbourhoods in England and the Netherlands (Scharf and de Jong Gierveld 2008), drawing on the same English data, noted that similar mechanisms connected neighbourhood characteristics and loneliness in both studies; notably, older people in both countries who evaluated their neighbourhood negatively tended to have higher loneliness scores. At country level, Nyqvist et al. (2019) found that welfare states, because of the provision of social protections, contribute to the absence of loneliness. The study found that the Nordic, Anglo-Saxon and Continental welfare regimes performed better than Southern and Eastern welfare regimes when it came to the absence of loneliness, suggesting that state provision of material resources can protect against loneliness. Hansen and Slagsvold (2015) investigated country differences in loneliness in Europe and found considerable between-country heterogeneity in late-life loneliness; especially among women, loneliness was strongly associated with lower socio-economic status.

The association between income inequality and loneliness was found in a study based on World Value Survey data from 43 countries, suggesting that poverty and income inequality have broad psychological consequences (Haushofer 2013). Similarly, based on SHARE data from 2013, Niedzwiedz et al. (2016, p. 29) found that the least wealthy older people had the highest risk of loneliness and concluded that there is a “need to consider social inequalities in loneliness as a public health issue among older people in Europe.” Yet the questions concerning the causal effect of poor material conditions on loneliness and their magnitude – given the complexity of the relationship – remain to be convincingly addressed. Our approach in this chapter aims to provide a contribution to this debate.

2.1 Other Relevant Risk Factors

In order to isolate the effect of material deprivation on loneliness, it is necessary to control for factors known to be associated with both material deprivation and loneliness. There is ample evidence that social contacts are protective against loneliness (e.g. Dykstra et al. 2005; Donovan et al. 2017), and being married or living with a partner is especially important for loneliness (e.g. Pikhartova et al. 2016) with recently widowed individuals at increased risk of loneliness (e.g. Dahlberg et al. 2015; Pikhartova et al. 2016). Cross-sectional studies have found that having no or fewer children is associated with loneliness (Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2016). Moreover, widowhood is also an important factor related to old-age poverty (Tinios et al. 2011; Bover et al. 2014), though on the other hand poverty and financial hardship among older people are often found to be higher in larger households (Lyberaki and Tinios 2008; Bover et al. 2014), most probably due to the fact that family solidarity and co-residence often act as a support mechanism to those with lowest resources.

Self-perceived health, co-morbidity, reduced health status and functional limitations have been found to be associated with both a higher risk of loneliness in older people (e.g. Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2009; Pikhartova et al. 2016; Hawkley and Kocherginsky 2017) and poor material conditions (Adena and Myck 2014; Bover et al. 2014; Franzese 2015).

Finally, an increased risk of loneliness has been found in women, although this association is usually non-significant when variables such as health and social factors are taken into account (e.g. Dahlberg et al. 2015; Hawkley and Kocherginsky 2017). Similarly, some studies have found higher age to be associated with loneliness in bivariate but not in multivariable analyses (e.g. Dahlberg et al. 2015; Pikhartova et al. 2016). However, the evidence regarding age is inconsistent in that other studies have not found this association (e.g. Warner and Adams 2016). These findings indicate that although loneliness may be more common in women and in people of higher ages, this can be explained by other factors such as the higher likelihood of loss of partner and other social relations, health problems and functional limitations in these groups. Analysis of SHARE data also suggests that age and being female is positively correlated with the risk of falling into financial hardship, although the key determinants of material conditions among older people are having labour market or retirement income and being in good health (Bover et al. 2014).

3 SHARE Data: Descriptive Statistics

For the purpose of our analysis we use the data from SHARE, a multidimensional panel study focused on individuals aged 50 years and older and covering key aspects of their lives such as health, labour market activity and retirement, material conditions as well as family and social relations (see e.g. Börsch-Supan et al. 2013). In our analysis we use information drawn from waves 5 and 6 of the survey, administered in 2013 and 2015 respectively. This is supplemented with additional retrospective data on childhood conditions from wave 3, when a full special life history interview was conducted, and wave 5 – from an additional module for those who did not participate in wave 3. The reason why we focus on these two waves is because the survey in wave 5 contained a special module specifically focused on broad aspects of well-being in later life and covering detailed data on material conditions. This allows us to use an indicator for material deprivation based largely on these extra variables. Additionally, both of these waves include a measure of loneliness, which enables the analysis of the relationship between loneliness and material conditions at a given point in time and over time. The analysis thus covers two waves of SHARE data and spans over 13 European countries which participated in SHARE in both of these waves: Austria, Germany, Sweden, Spain, Italy, France, Denmark, Switzerland, Belgium, Czech Republic, Luxembourg, Slovenia and Estonia. The final sample sizes used in the analysis of levels and changes in loneliness, together with basic descriptive statistics, are presented in Table 24.1. The respective total samples consist of 30,072 and 18,954 individuals.

In Table 24.1 we show the gender composition of the sample, the proportion of respondents living with a partner, the proportion of those reporting poor health status and the proportion of those working at the time of wave 5. There is large cross-country heterogeneity in particular with regard to the latter two characteristics. While only 3.0% of the sample report poor health in Switzerland, as many as 22.4% do so in Estonia, and rates of paid employment vary from 17.7% in Austria to 45.1% in Denmark.Footnote 2 We also present the proportion of the specific country samples who are in the highest and the second highest quintiles of material deprivation – measured via the material deprivation index constructed on the basis of the additional survey items available in the SHARE Survey in wave 5.

The index aggregates a set of binary indicators on whether a person is deprived of a specific item applying weights related to how a given item affects individual welfare (see Adena et al. 2015; Bertoni et al. 2015; Myck et al. 2015).Footnote 3 The final deprivation index takes values from zero to one, with higher values implying higher levels of deprivation. There is a number of advantages of using such indices to measure material conditions, especially in an international context. In particular, the indices are comparable across countries, since they refer to the same list of items, and they are comprehensive measures capturing a broader concept of material conditions compared to income or assets with a specific focus on the material needs of older people. In the analysis, we use information on the respondents’ position in the distribution of material deprivation and focus on the top two quintiles – those in the highest 20% and the second highest 20% of material deprivation. There is very high variation in the proportion of respondents who face material deprivation in different countries. The proportion of individuals who belong to the highest quintile of material deprivation in the full SHARE sample in wave 5 varies from 3.3% in Denmark to as much as 48.2% in Estonia [see Sumil-Laanemaa et al. this volume for a discussion of this variation by welfare clusters]. Similarly, 9.2% and 28.3% of respondents are located in the second quintile of the overall material deprivation distribution in the two countries respectively. Our measure of loneliness is based on three items in the SHARE survey available in waves 5 and 6 which are based on the following questions [as also used by Morgan et al. this volume]:

-

How much of the time do you feel you lack companionship?

-

How much of the time do you feel left out?

-

How much of the time do you feel isolated from others?

Each of these questions has three response categories: “Often”, “Some of the time” or “Hardly ever or never”. On the basis of these three questions we identify people as being in mild or severe loneliness depending on whether they report: “Some of the time” or “Often” to either of the three questions, respectively.

In columns 2 and 3 of Table 24.2, we present the levels of mild and severe loneliness across countries in the sample used for the levels analysis. About a quarter of the entire SHARE sample in these 13 countries in wave 5 reported mild loneliness – with rates varying between 14.5% in Denmark to 33.1% in Estonia. Eight per cent of the sample experience severe loneliness, with lowest rates in Switzerland, Denmark and Austria (between 3.4% and 3.7%) and highest rates in Estonia, Czech Republic and Italy (from 12.6% to 13.0%). In columns 4 and 5 we present the proportion of respondents among those who in wave 5 report no loneliness, and who in wave 6 report either mild or severe loneliness. Nearly 20% of all respondents who did not report loneliness at the time of wave 5, report falling into mild loneliness and 3.4% into severe loneliness over the two-year period. The highest proportion of those who fall into severe loneliness are once again found in Estonia (7.0%) and the Czech Republic (7.2%).

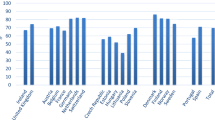

In Fig. 24.1, we present the distribution of the populations for a selection of six of the thirteen countries we use for analysis, conditional on their loneliness and material deprivation status. Each population is divided into six categories. The first three include people who do not report loneliness and:

-

are in the bottom three quintiles of material deprivation (Category 1)

-

are in the second highest quintile of material deprivation (Category 2)

-

are in the highest quintile of material deprivation (Category 3)

While the last three categories include those who report mild or severe loneliness and similarly:

-

are in the bottom three quintiles of material deprivation (Category 4)

-

are in the second highest quintile of material deprivation (Category 5)

-

are in the highest quintile of material deprivation (Category 6)

The categories reflect the differences between the scale of reported loneliness in the respective countries, and within these we can distinguish the scale of material deprivation. The top three categories (4–6) cover respondents who declare some degree of loneliness. If we treat loneliness and material deprivation as reflections of two different aspects of social exclusion, we can see a significant overlap between the two dimensions. For example, in Estonia nearly 24% of the SHARE sample report some degree of loneliness and at the same time fall into the highest quintile of material deprivation. In Italy this proportion is as high as 17.2%, while the proportion in Belgium and Denmark is 4.9% and 1.0% respectively.

4 Data Analysis

The main focus of our analysis is to relate poor material conditions to loneliness in later life and to try to identify if material conditions have causal implications for the dynamics of loneliness. Generally the relationship could be summarised in the following equation:

where Li,t is a measure of loneliness of individual i at time t, Xi,t are his or her characteristics, mci,t is the individual indicator (or a vector of indicators) of poor material conditions, i.e. our key variable of interest, and ɛi,t is an individual, t-specific residual. Naturally, the above specification is unable to identify the causal role of material conditions on loneliness due to the potential endogeneity of the former with respect to the latter, since loneliness at time t might be caused by poor material conditions and vice versa. In addition, there may be factors in ɛi,t which are correlated with both material conditions and loneliness which would result in a biased estimation of the coefficient on mci,t. We take several steps to reduce this bias. Firstly, we control for an extensive set of potential risk factors identified in previous research and making use of the richness of the SHARE data. In the Xi,t vector of variables we include those related to physical health, family relations, as well as childhood conditions drawn from life history interviews of the survey. Second, apart from examining the basic relationship in levels, as presented in Eq. 24.1, we take advantage of the panel nature of the SHARE survey and look at the correlation of material conditions and other factors with dynamics of loneliness. This is done by taking a sample of respondents who did not show any signs of loneliness in wave 5 (see Table 24.1) and examining the role of various factors on the probability of falling into loneliness by wave 6 (see Table 24.2). With this approach – through the differences in loneliness scores between the waves – we account for some of the so called “fixed effects” which might affect both material conditions and loneliness and as a result bias the examined relationship (for another application of this approach see Myck et al. 2019).

The vector of control variables in the levels specifications, which are based on wave 5 data, includes such characteristics as: gender, age polynomial, years of education, living in a rural area, work status, a set of controls for physical health, for having a partner, the size of the household, number of sons, number of daughters, number of children living close to the respondent (within 5 km radius), as well as indicators for: ever having siblings, having a living sister, brother, mother and father. The set of controls which cover characteristics from retrospective interviews related to the situation of the respondent at the age of 10 includes such information as accommodation conditions, number of books at home, relative performance at school in native language and maths, vaccinations and health status during childhood. Naturally, we also control for country-fixed effects. Additionally, the specifications in changes are extended to include information on: leaving work, losing a partner and changes in the size of the household between waves 5 and 6. Standard errors are clustered at the country level and estimates are conducted using linear probability models. The dependent variables are binary indicators for reporting either any loneliness (mild or severe) or severe loneliness.

5 Results: Material Deprivation and Loneliness

Results of our analysis are presented in Table 24.3 in four specifications. Specifications one and two present the relationship in levels of loneliness, as reported in wave 5 of SHARE, while specifications three and four show the results in changes between waves 5 and 6 (from reporting no expressions of loneliness in wave 5). In each case, the first specification shows the relationship for any loneliness, mild or severe, and the second for severe loneliness. In Table 24.3 we only report a selection of coefficients with the remaining ones shown only with respect to the joint significance of the entire group of factors divided into health, family and childhood variables. In all specifications we control for the level of material deprivation through the indicators of belonging to either the first or second quintile of the distribution.

5.1 The Role of Control Factors

The results show a very clear and consistent pattern. First of all we see a significant effect of age in all specifications, and while the coefficients on age is negative the curvature of the relationship picked up by controlling for age squared shows that, while age initially is associated with lower loneliness – or lower probability of falling into loneliness – at a certain point, the relationship turns negative and loneliness begins to grow for older-ages. Detailed analysis of the two coefficients suggests that this tipping point is around the age of between 64 and 67 years. Neither the gender of the respondent nor his or her education seems to have a consistently significant effect on the levels of loneliness. We also find no correlation between loneliness and living in a rural area. Working at the time of wave 5 is associated with lower levels of loneliness and reduces the probability of falling into mild or severe loneliness but has no effect on the probability of falling into severe loneliness, and we find no effect of leaving work after wave 5 on the probability of reporting loneliness 2 years later. Partnership status and the experience of losing one’s partner between waves 5 and 6 is strongly and significantly correlated with the level and change in loneliness. In the latter case, the probability of falling into severe loneliness grows by 16.4 percentage points (pp), and reporting any expression of loneliness in wave 6 grows by as much as 32.2 pp. among those who lost their partner. While the overall household size does not seem to reduce the probability of falling into loneliness, a reduction of household members between waves 5 and 6 increases the probability of falling into severe loneliness by 1.6 pp. In all specifications we find that the groups of variables related to physical health, extended family as well as childhood conditions are all significantly related to both levels and changes in loneliness [also see Morgan et al. this volume].

5.2 Loneliness and Material Deprivation

Turning to the role of material conditions, our results show that being located in the highest or the second highest quintile of the material deprivation distribution is strongly associated with both the level of loneliness (specifications 1 and 2) and with falling into loneliness in wave 6 conditional on not reporting loneliness 2 years earlier. Being in the highest quintile of the distribution is associated with a nearly 4.8 pp. higher probability of falling into loneliness in wave 6 and with a 2.0 pp. higher probability of falling into severe loneliness (compared to those in the bottom three quintiles). Given that, as we saw in Table 24.1, the average probability of falling into severe loneliness is only 3.3%, this suggests a potentially very important role of material conditions in affecting the level of loneliness among older people. The probability of falling into severe loneliness among those in the second highest quintile of the material deprivation distribution is also higher (by 1.1 pp) compared to those further down the deprivation scale (i.e. those less deprived) and the effect is also statistically significant.

6 Discussion

This chapter primarily focused on two domains of social exclusion: economic exclusion – in the form of material resources – and exclusion from social relations – in the form of loneliness. The aim was to examine the dynamic effect of material exclusion on loneliness, through an analysis of the longitudinal data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE).

The finding that older people living in materially deprived conditions is strongly associated with loneliness adds to the growing body of evidence, cited earlier in this chapter, on this critical risk factor. This finding was strong, both in terms of the cross-sectional analysis for the earlier wave, and the dynamic analysis between the two waves for those who were not lonely during 2013 but became lonely in 2015. Being located in the highest or the second highest quintile of the material deprivation distribution is strongly associated with both the level of loneliness and with falling into loneliness in wave 6 demonstrating increasing negative impacts over time. The analysis focussed on the highest two deprivation quintiles to highlight the impact of material deprivation on the levels of loneliness for older people experiencing lower living standards. This result supports earlier findings of Cohen-Mansfield et al. (2009) who also found that poor material conditions have implications for the onset of loneliness.

The variables used as controls in this research largely confirmed previous studies, presented earlier in this chapter. Having a partner is protective against loneliness and losing a partner is strongly associated with an increase in loneliness. Growing older and having a reduction in the number of people in one’s household between the two waves are both associated with loneliness, but not as strongly. Being in work correlates with lower levels of loneliness, but we find no relationship between work (and leaving it) and becoming severely lonely between the waves. Gender, education and living in a rural area did not demonstrate consistently significant effects. However, the overall grouping of variables on physical health and childhood conditions confirmed earlier research findings with physical health being protective and negative childhood conditions providing a risk.

Given the robust links of loneliness to overall negative morbidity and mortality outcomes (Holt-Lunstad et al. 2015), our research findings provide important pointers for developing our understanding of causal relations in a complex reality of overlapping domains of exclusion. The results demonstrate the implications of material exclusion on changes in the degree of loneliness and as such, the effect of economic related factors, in this case material resources, on social relations. Poor material conditions may influence people’s welfare directly, but on top of this they seem to affect the standard of living also through negative impacts on social relations and other domains further down the line.

7 Conclusion

The findings raise a number of important questions about the role of poor living conditions on loneliness and social exclusion more generally. For example, does material deprivation lead some older people to being shy about initiating and sustaining relationships because they feel they have nothing that is attractive to give others? Does a lower standard of living lead to negative psychological responses such as a loss of self-worth and a sense of shame that may inhibit social connection and deepen the experience of loneliness? Do lower living conditions create affordability stress as older people endeavour to balance their budgets between food, housing, utilities and other goods and services to such an extent that they find it difficult to afford socially connecting activities? Future research can explore these questions to illuminate further the interrelationships between the economic and social domain of exclusion in later life.

The results also raise important policy issues. The cost of loneliness on health and welfare budgets is considerable (Public Health England 2017). An increased investment in material living standards may therefore lead to lower healthcare and welfare costs over time and a better life in a number of dimensions for people currently living in materially deprived conditions.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

Note that the rates are not adjusted for age composition and some of this variation may be related to this because countries refresh their panel samples at different stages. We control for age in all our detailed analysis.

- 3.

The items relate to: (a) affordability of: meat/fish/chicken, fruits/vegetables, an unexpected expense, a week-long vacation once a year, regular grocery shopping; (b) keeping living costs down by: reducing heating, wearing worn-out shoes, wearing worn-out clothes, not replacing glasses, postponing dentist, postponing doctor; (c) having payment arrears (d) experiencing insufficient resources to do things that one would like to do. See: Bertoni, Cavapozzi, Celidoni, & Trevisan, 2015.

References

Adena, M., & Myck, M. (2014). Poverty and Transitions in Health in Later Life. Social Science and Medicine, 116, 202–210.

Adena, M., Myck, M., & Oczkowska, M. (2015). Material deprivation – in SHARE Wave 5 data: A contribution to a better understanding of differences in material conditions in later life. In A. Börsch-Supan, T. Kneip, H. Litwin, M. Myck, & G. Weber (Eds.), Ageing in Europe: Supporting policies for an inclusive society (pp. 25–38). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Bertoni, M., Cavapozzi, D., Celidoni, M., & Trevisan, E. (2015). Assessing the material deprivation of older Europeans. In A. Börsch-Supan, T. Kneip, H. Litwin, M. Myck, & G. Weber (Eds.), Ageing in Europe: Supporting policies for an inclusive society (pp. 49–56). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Börsch-Supan, A. (2017). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Waves 3, 5 and 6. Release version: 6.0.0. SHARE-ERIC.

Börsch-Supan, A., Brandt, M., Hunkler, C., Kneip, T., Korbmacher, J., Malter, F., et al. (2013). Data resource profile: The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(4), 992–1001. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt088.

Bover, O., Brugiavini, A., & Weber, G. (2014). Anatomy of financial hardship. In A. Brugiavini & G. Weber (Eds.), Longer-term consequences of the great recession on the lives of Europeans (pp. 4–37). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burholt, V., Winter, B., Aartsen, M., Constantinou, C., Dahlberg, L., Feliciano, V., et al. (2019). 156 A critical review and development of a conceptual model of exclusion from social relations for older people. European Journal of Ageing, 17, 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-019-00506-0.

Cohen-Mansfield, J., Hazan, H., Lerman, Y., & Shalom, V. (2016). Correlates and predictors of loneliness in older-adults: a review of quantitative results informed by qualitative insights. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(4), 557–576. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610215001532.

Cohen-Mansfield, J., Shmotkin, D., & Goldberg, S. (2009). Loneliness in old age: longitudinal changes and their determinants in an Israeli sample. International Psychogeriatrics, 21(6), 1160–1170. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610209990974.

Dahlberg, L., Andersson, L., McKee, K. J., & Lennartsson, C. (2015). Predictors of loneliness among older women and men in Sweden: A national longitudinal study. Aging and Mental Health, 19(7), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.944091.

de Jong Gierveld, J., & Tesch-Römer, C. (2012). Loneliness in old age in Eastern and Western European societies: theoretical perspectives. European Journal of Ageing, 9(4), 285–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-012-0248-2.

de Jong Gierveld, J., van Tilburg, T. G., & Dykstra, P. A. (2006). Loneliness and social isolation. In A. Vangelisti & D. Perlman (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of personal relationships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Donovan, N. J., Wu, Q., Rentz, D. M., Sperling, R. A., Marshall, G. A., & Glymour, M. M. (2017). Loneliness, depression and cognitive function in older US adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(5), 564–573. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4495.

Dykstra, P. A., van Tilburg, T. G., & de Jong Gierveld, J. (2005). Changes in older adult loneliness: Results from a seven-year longitudinal study. Research on Aging, 27(6), 725–747. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027505279712.

Eurostat. (2018). Glossary: Material deprivation. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Material_deprivation.

Fokkema, T., Gierveld, J. D., & Dykstra, P. A. (2012). Cross-national differences in older adult loneliness. Journal of Psychology, 146(1–2), 201–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.631612.

Franzese, F. (2015). Slipping into poverty: effects on mental and physical health. In A. Börsch-Supan, T. Kneip, H. Litwin, M. Myck, & G. Weber (Eds.), Ageing in Europe: Supporting policies for an inclusive society (pp. 139–148). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Gibney, S., Moore, T., & Shannon, S. (2019). Loneliness in later life: a cross-sectional survey analysis of place-based factors in Ireland. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 20(2), 80–96. https://doi.org/10.1108/qaoa-04-2018-0015.

Hansen, T., & Slagsvold, B. (2015). Late-life loneliness in 11 European countries: results from the generations and gender survey. Social Indicators Research, 124(1), 1–20.

Haushofer, J. (2013). The Psychology of Poverty: Evidence from 43 Countries. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Hawkley, L. C., & Kocherginsky, M. (2017). Transitions in loneliness among older adults: A 5-year follow-up in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. Research on Aging, Published online ahead of print 17 March 2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027517698965.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352.

Lyberaki, A., & Tinios, P. (2008). Poverty and Persistent Poverty: Adding Dynamics to Familiar Findings. In A. Börsch-Supan et al. (Eds.), Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (2004–2007). Starting the Longitudinal Dimension. Mannheim: Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging.

Myck, M., Najsztub, M., & Oczkowska, M. (2015). Measuring social deprivation and social exclusion. In A. Börsch-Supan, T. Kneip, H. Litwin, M. Myck, & G. Weber (Eds.), Ageing in Europe. Supporting policies for an inclusive society (pp. 67–78). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Myck, M., Oczkowska, M., & Najsztub, M. (2019). Implications of social and material deprivation for changes in health of older people Journal of Aging and Health, (January), 1–25.

Niedzwiedz, C. L., Richardson, E. A., Tunstall, H., Shortt, N. K., Mitchell, R. J., & Pearce, J. R. (2016). The relationship between wealth and loneliness among older people across Europe: Is social participation protective? Preventive Medicine, 91, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.07.016.

Nyqvist, F., Nygard, M., & Scharf, T. (2019). Loneliness amongst older people in Europe: a comparative study of welfare regimes. European Journal of Ageing, 16(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-018-0487-y.

Pikhartova, J., Bowling, A., & Victor, C. (2016). Is loneliness in later life a self-fulfilling prophecy? Aging & Mental Health, 20(5), 543–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1023767.

Public Health England. (2017). Commissioning cost-effective services for promotion of mental health and wellbeing and prevention of mental ill-health. London: PHE Publications.

Scharf, T., & de Jong Gierveld, J. (2008). Loneliness in urban neighbourhoods: an Anglo-Dutch comparison. European Journal of Ageing, 5(2), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-008-0080-x.

Scharf, T., Phillipson, C., & Smith, A. E. (2005). Social exclusion of older people in deprived urban communities of England. European Journal of Ageing, 2(2), 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-005-0025-6.

Tesch-Römer, C., & Huxhold, O. (2019). Social Isolation and Loneliness in Old Age. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Subject: Developmental Psychology. https://oxfordre.com/psychology/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.001.0001/acrefore-9780190236557-e-393#acrefore-9780190236557-e-393-div1-2.

Tinios, P., Lyberaki, A., & Georgiadis, T. (2011). Explaining Persistent Poverty in SHARE: Does the Past Play a Role? In A. Börsch-Supan et al. (Eds.), The Individual and the Welfare State (pp. 19–29). Berlin\Heidelberg: Springer.

Warner, D. F., & Adams, S. A. (2016). Physical disability and increased loneliness among married older adults: The role of changing social relations. Society and Mental Health, 6(2), 106–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869315616257.

Editors’ Postscript

Please note, like other contributions to this book, this chapter was written before the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. The book’s introductory chapter (Chap. 1) and conclusion (Chap. 34) consider some of the key ways in which the pandemic relates to issues concerning social exclusion and ageing.

Data Acknowledgement

This paper uses data from SHARE Waves 3, 5 and 6 (DOIs: https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w3.600, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w5.600, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w6.600; Börsch-Supan, 2017), see Börsch-Supan et al. (2013) for methodological details. The SHARE data collection has been primarily funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812) and FP7 (SHARE-PREP: N°211,909, SHARE-LEAP: N°227,822, SHARE M4: N°261,982). Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06–11, OGHA_04–064, HHSN271201300071C) and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Myck, M., Waldegrave, C., Dahlberg, L. (2021). Two Dimensions of Social Exclusion: Economic Deprivation and Dynamics of Loneliness During Later Life in Europe. In: Walsh, K., Scharf, T., Van Regenmortel, S., Wanka, A. (eds) Social Exclusion in Later Life. International Perspectives on Aging, vol 28. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51406-8_24

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51406-8_24

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-51405-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-51406-8

eBook Packages: HistoryHistory (R0)