Abstract

While the subset of introduced species that become invasive is small, the damages caused by that subset and the costs of controlling them can be substantial. This chapter takes an in-depth look at the economic damages non-native species cause, methods economists often use to measure those damages, and tools used to assess invasive species policies. Ecological damages are covered in other chapters of this book. To put the problem in perspective, Federal agencies reported spending more than half a billion dollars per year in 1999 and 2000 for activities related to invasive species ($513.9 million in 1999 and $631.5 million in 2000 (U.S. GAO 2000)). Approximately half of these expenses were spent on prevention. Several states also spend considerable resources on managing non-native species; for example, Florida spent $127.6 million on invasive species activities in 2000 (U.S. GAO 2000), and the Great Lakes states spend about $20 million each year to control sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) (Kinnunen 2015). Costs to government may not be the same as actual damages, which generally fall disproportionately on a few economic sectors and households. For example, the impact of the 2002 outbreak of West Nile virus exceeded $4 million in damages to the equine industries in Colorado and Nebraska alone (USDA APHIS 2003) and more than $20 million in public health damages in Louisiana (Zohrabian et al. 2004). Zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) cause $300–$500 million annually in damages to power plants, water systems, and industrial water intakes in the Great Lakes region (Great Lakes Commission 2012) and are expected to cause $64 million annually in damages should they or quagga mussels (Dreissena bugensis) spread to the Columbia River basin (Warziniack et al. 2011).

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

14.1 Introduction

While the subset of introduced species that become invasive is small, the damages caused by that subset and the costs of controlling them can be substantial. This chapter takes an in-depth look at the economic damages non-native species cause, methods economists often use to measure those damages, and tools used to assess invasive species policies. Ecological damages are covered in other chapters of this book. To put the problem in perspective, Federal agencies reported spending more than half a billion dollars per year in 1999 and 2000 for activities related to invasive species ($513.9 million in 1999 and $631.5 million in 2000 (U.S. GAO 2000)). Approximately half of these expenses were spent on prevention. Several states also spend considerable resources on managing non-native species; for example, Florida spent $127.6 million on invasive species activities in 2000 (U.S. GAO 2000), and the Great Lakes states spend about $20 million each year to control sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) (Kinnunen 2015). Costs to government may not be the same as actual damages, which generally fall disproportionately on a few economic sectors and households. For example, the impact of the 2002 outbreak of West Nile virus exceeded $4 million in damages to the equine industries in Colorado and Nebraska alone (USDA APHIS 2003) and more than $20 million in public health damages in Louisiana (Zohrabian et al. 2004). Zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) cause $300–$500 million annually in damages to power plants, water systems, and industrial water intakes in the Great Lakes region (Great Lakes Commission 2012) and are expected to cause $64 million annually in damages should they or quagga mussels (Dreissena bugensis) spread to the Columbia River basin (Warziniack et al. 2011).

Studies on economic impacts from invasive species vary in their rigor and usefulness for informing policy decisions. This chapter discusses economic impacts and methods used to calculate them, how to distinguish impact studies that were done well from those that were done poorly, and appropriate use of values calculated in impact studies. The chapter also discusses key contributions of economics to invasive species science and provides a quick overview of behavioral and economic responses to invasive species risk.

The chapter is organized according to four main themes. The first section focuses on introduction and establishment of species into an area. Economic research on the introduction of species has focused on people’s understanding of invasion risk and potential impacts and how they respond to that risk, human-mediated vectors of introductions, and development of trade and regulatory policies that prevent the movement of invasive species into uninvaded areas. The second section provides an overview of methods used to measure damages and costs related to invasive species. There exists a rather mature literature on market damages from invasive species, a maturing literature on non-market damages from invasive species, and a very young literature linking the production of ecosystem services with their market and non-market values. These estimates are essential to formulate a realistic examination of policy, as discussed in the third section on optimal policies and strategies for preventing and controlling invasive species. New models on optimal policy link introduction and establishment through the use of geographical models that depict invasion and its negative impacts in temporal and spatial domains. Such models indicate that establishment in one area makes introduction into neighboring areas more likely, and are often used to estimate the cost-effectiveness of control or slow-the-spread measures that are applied, subject to geographic constraints on policy and various environmental variables. The chapter concludes with a discussion of future research needs and a table (Table 14.1) summarizing damages from invasive species found in the literature.

14.2 Introduction of Invasive Species, Risk Perceptions, and Human Vectors

More than 450 species of non-native forest insects and at least 16 pathogens have been established and detected in the United States since 1860, with approximately 2.5 established non-native forest insects detected per year between 1860 and 2006 (Aukema et al. 2010). Intentional introductions attributed to nurseries, botanical gardens, and private plant enthusiasts are responsible for most introductions of terrestrial plant species into the United States (Reichard and White 2001). Unintentionally introduced species, often called “hitchhikers,” arrive on trade and transportation vectors. For example, herbaceous invasive species are often introduced through crop seed contamination (Baker 1986; Mack 1991); aquatic species are often introduced via biofouling and ship ballast water (Baker 1986; Drake and Lodge 2007; Keller et al. 2011); wood-boring insects are often introduced with wood packaging materials and by movement of fuel wood (Barlow et al. 2014; IPPC 2002; Jacobi et al. 2011; Koch et al. 2012; Liebhold and Tobin 2008; McNeely et al. 2001); and non-native plant insects and diseases often arrive on live plant imports (Liebhold et al. 2012). Nearly 70% of damaging forest insects and pathogens established in the United States between 1860 and 2006 most likely entered on imported live plants (Liebhold et al. 2012).

Human-mediated transport facilitates the spread of non-native species populations at rates and distances well beyond what would occur naturally (Blakeslee et al. 2010). Patterns of historical trade and settlement (Brawley et al. 2009), marine trade, road transportation (Bain et al. 2010; Kaluza et al. 2010; Yemshanov et al. 2013), and recent economic and demographic changes (Pysek et al. 2010) have all been linked to the distribution of invasive species. In recent decades, long-distance transport of raw commodities of both domestic and international trade has grown as a key driver of species spread (Aukema et al. 2010; Bain et al. 2010; Pysek et al. 2010; Warziniack et al. 2013), a trend that is expected to continue as the proportional growth of trade volume exceeds rates of economic growth (UNCTAD 2007; WTO 2008).

Non-native insects, pathogens, and other organisms are often inadvertently transported to novel territories in shipping containers and commercial transports where they may become established as ecologically and/or economically harmful invasive species (Hulme et al. 2008; Hulme 2009; Kaluza et al. 2010; Lounibos 2002; Tatem et al. 2006; Westphal et al. 2008). While the rate of accumulation of forest pests has been relatively constant since 1860 (Aukema et al. 2010), changes in trade and phytosanitary practices have likely altered the relative importance of particular pathways. For example, Aukema et al. (2010) found that establishment of wood-borers increased faster than any other insect guild since the 1980s; they attributed this increase to the increased volume of containerized freight and accompanying wood packaging material. The magnitude of economic factors that influence trade flows (and the potential introductions of non-native species) is projected to increase (Pysek et al. 2010). Hopefully, analyses of evolving world trade networks can facilitate the development of new approaches for preventing the movement of non-native species (Banks et al. 2015). Recent analyses have shown the increasing importance of countries such as China and South Korea as world trade hubs (Fagiolo et al. 2010), a trend that is consistent with increasing detections of wood-boring insects originating from Asia. Although it is difficult to demonstrate the effectiveness of international trade policies on the rate of accumulation of forest pests, Lovett et al. (2016) find that rates of introduction to the United States from China of wood-boring species decreased after policies were put in place that require phytosanitary treatment of wood packing material.

Several modeling approaches have been developed that take into account local and long-distance dispersal (due to factors such as transportation networks). For example, gravity models and random utility models have been used to predict invasions when human-mediated dispersal is important (Bossenbroek et al. 2009; Chivers and Leung 2012). Each takes into account distance as well as the attractiveness of alternative locations, and therefore can incorporate differential traffic to each site and its consequences on patterns of spread.

Eliminating all risks of invasive species to a region is usually not possible without significantly affecting local economies, so economic research often focuses on the “right” amount of risk, or the “optimal amount of invaders.” Risk of introduction is assessed in relation to the appeal of owning exotic species (e.g., exotic house and landscaping plants, aquarium plants and fish, and exotic pets), the role of trade in economic growth, and gains from trade (Fraser and Cook 2008; Knowler and Barbier 2005; Warziniack et al. 2013). When considering protective regulations, agencies face the possibility of making Type I (false positive) and Type II (false negative) errors, which can lead to either over-regulation or under-regulation, respectively. The challenges associated with quantifying the costs of Type II errors, in combination with political influences (Simberloff 2005), may cause biosecurity agencies to focus on minimizing the costs associated with Type I errors (e.g., management costs) while neglecting the potential for economic damage (Davidson et al. 2015).

By controlling the vectors of introduction or influencing the composition of goods produced in a region, managers can affect exposure (Tu et al. 2008), and thus should an invasion occur, people can adapt to environmental changes (Settle and Shogren 2004). Not only does the environment respond to human activity, but human activity also responds to environmental conditions (Finnoff et al. 2005; Merel and Carter 2008; Shogren 2000). Damage estimates should be sensitive to the fact that people can adjust their behavior both pre and post invasion. For example, Finnoff et al. (2010) proposed an endogenous risk framework in which probability of a species’ presence in the transportation network depends on prevention choices. Should an invasive species enter the transportation network, managers can try to either eradicate the species or control it to reduce severity of damages. Should all efforts prove either ineffective or too costly, society can limit damages through adaptation.

14.3 Establishment of Species in an Area and Measurement of Damages

The presence of harmful non-native organisms causes damages to economically valuable host resources and negatively affects the state of native ecosystems and economically important crops. Assessing economic risks entails a valuation of economic consequences and impacts from an introduction and spread of non-native organisms. The severity of economic damages may justify the establishment of quarantine and other regulatory actions aimed at containing the invading populations or, if containment is no longer possible, at slowing the rate of spread. This section discusses the state of the science for valuation methods used in those decisions.

Partial Budgeting, Replacement Costs, and Costs of Control

Partial budgeting helps evaluate the economic consequences of small adjustments in production (such as agricultural crop production) and is based on the principle that a small change in production may reduce some costs and revenues while adding other costs and revenues (Soliman et al. 2010). Partial budgeting methods generally focus on the net decrease or increase in income resulting from a change in production. The method requires a relatively modest amount of data and personnel time (Holland 2007); accordingly, it has been widely used to assess the economic impacts of agricultural and forest pests (FAO IPPC 2004; Macleod et al. 2003). While the analyses can be scaled up to the national level (see Breukers et al. 2008; Macleod et al. 2003), the method cannot measure multi-sectorial impacts because it relies on fixed budgets with defined prices to describe the economic activities of the firm or enterprise (Soliman et al. 2010).

Using replacement and control costs to estimate the economic impact of an invasive species is also a relatively straightforward and easy way to interpret and measure damages. For example, to estimate the economic impact of emerald ash borer (EAB), Agrilus planipennis, Kovacs et al. (2010) estimated the discounted cost of treatment, removal, and replacement of landscape ash (Fraxinus spp.) trees on developed land within communities in a 25-State study area centered on Detroit using simulations of EAB spread and infestation over the next decade (2009–2019). An estimated 38 million ash trees exist on this land base. The simulations predicted an expanding EAB infestation that will likely encompass most of the 25 States and warrant treatment, removal, and replacement of more than 17 million ash trees with a discounted cost equal to $10.7 billion. Note that replacement and control costs address only one side of the cost-benefit analysis; they do not determine whether or not those costs are worth incurring.

Single-Industry Impacts (Partial Equilibrium Models)

Partial equilibrium modeling represents another common assessment technique, especially useful when an invasion is expected to change the producers’ surplus or consumers’ demand value (Mas-Colell et al. 1995). The methodology evaluates the welfare effects on participants in a market that is affected by an introduction of a harmful non-native species. The approach defines relationships for supply and demand for the commodity of interest (such as agricultural or forest commodities that may be negatively affected by the introduction of the invader) to determine the final combination of prices and quantities that leads to a market equilibrium (Mas-Colell et al. 1995).

As shown in Box 14.1 on partial equilibrium impacts, such models estimate the aggregate impact of a non-native species by measuring differences in equilibrium price and quantity and changes in welfare before and after the introduction. Introduction of harmful organisms may lead to an increase in the production costs and a decrease in the quantity (or quality) of a susceptible host resource (such as valuable crops or forest tree species), which also affects the supply curve and the equilibrium price. Changes in welfare are estimated from the aggregated changes in producers’ and consumers’ welfare (Just et al. 1982). Partial equilibrium models have been used widely as policy assessment tools in agriculture, forestry, and trade (Cook 2008; Elobeld and Beghin 2006; Holmes 1991; Kaye-Blake et al. 2008; Qaim and Traxler 2005; Schmitz et al. 2008), for risk assessments of quarantine pests (Arthur 2006; Breukers et al. 2008; Surkov et al. 2009), and to evaluate changes in exports and access to markets (Cook 2008; Elliston et al. 2005; Julia et al. 2007).

Box 14.1: Partial Equilibrium Model of Invasive Species Impacts

Consider the following example, adapted from Arthur (2006), that looks at the trade-off between gains from trade to Australian apple consumers and damages from an invasive apple blight. Without trade, the domestic production of apples in Australia is Q0, and Australian consumers pay P0. Pre-trade welfare is measured by the sum of consumer surplus (triangle XP0Y, the area below the demand curve D but above the price) and producer surplus (ZP0Y, the area above the initial supply curve S0 but below the price). Opening the market to trade allows consumers to buy apples at world price PW, which increases consumption to Q1 and decreases domestic production to Q2. Producer surplus falls to PWTZ, but consumer surplus increases to XPWU. The shaded triangle marked GAINS represents the increase in welfare from trade. Trade, however, also brings potential damages from apple blight. Prevention measures and crop damages increase costs of production to Australian growers, causing the domestic supply curve to shift to SINV and domestic production to fall to QINV. Consumer surplus is not affected, but producer surplus shrinks. The shaded area marked LOSS shows the loss to Australian apple growers from the invasion. The total impact of trade, accounting for losses of invasion, is GAINS – LOSS, which could be either positive or negative.

Economy-Wide Impacts (Input-Output and Computable General Equilibrium Models)

Input-output and computable general equilibrium (CGE) models are used when impacts from invasive species are likely to affect multiple sectors of the economy, when indirect effects are likely due to impacts on factors of production, or when income effects are likely to be large. Input-output analysis elucidates the interdependencies of sectors in an economy and predicts an economy-wide impact of changes within a particular sector (Leontief 1986). Input-output analysis also requires a description of the monetary flows of inputs and outputs among the productive sectors of an economy (Miller and Blair 1985). Changes in product demands in a sector generate effects on the economy as a whole and cause direct changes in the purchasing policies of the affected sector. The suppliers of the affected sector must change their purchasing policies in order to satisfy the changed demands, and so on. Input-output analysis can estimate the impact of an invasive species on an economy by adjusting the final demand in the affected sector (such as agriculture or forestry) in response to the expected changes in demand (such as decrease in the production of agricultural commodities or reduction in exports) (Elliston et al. 2005; Julia et al. 2007). Overall, the approach helps measure short-term impacts across broad sectors of the economy.

CGE models are composed of sets of equations that specify demand, production, and interactions between domestic production and imports, prices, and other equilibrium conditions. CGE models are similar in flavor to input-output models, but they place more emphasis on the behavioral equations that underlie the economic system and allow for price adjustments. CGE helps assess economy-wide impacts across sectors and regions, and considers long-term consequences. CGE models are also appropriate when assessing impacts of trade restrictions due to invasive species policy and when agents in the economy can substitute away from sectors of the economy impacted by the invasion (Warziniack et al. 2011). Using the invasive emerald ash borer as an example, McDermott et al. (2013) developed a CGE model for the State of Ohio and estimated annual damages from the beetle to be about $70 million. The majority of this damage ($57 million) is incurred by the parks and recreation sectors, households, and State government. The parks and recreation sectors must add the costs of removing infested ash trees to their primary production costs. Households must reduce their disposable income by the cost of ash removal while these expenditures flow to the garden sector as an increase in demand for their services. The government must make revenue adjustments to account for ash removal with those expenditures moving to the garden sector.

Impacts on Non-market Values and Ecosystem Services

Some more difficult-to-assess risks include impacts on social infrastructure, recreational use (such as fishing), existence values of native species threatened by invasive species, aesthetics, and factors associated with human health (such as water quality). The value of damages and impacts on these ecosystem services is more difficult to measure because these services are not traded in markets and therefore do not have observable prices. Thus, economists estimate the value of changes in non-market ecosystem services by leveraging the information conveyed by individuals’ observable decisions. Information obtained from observable decisions in hypothetical markets created by the analyst is known as stated preference data. In contrast, revealed preference data are obtained from observable choices concerning “consumption” of non-market ecosystem services such as where to recreate, how votes on ballot referenda might influence non-market ecosystem services, and how people behave in markets for a weak complement to the non-market ecosystem service. In such cases, the choices and trade-offs people make reflect their willingness to pay to access or obtain ecosystem services.

Stated and revealed preference methods used to estimate the value of non-market ecosystem services are reviewed by Ninan (2014) and Binder et al. (2016). Applications to estimate people’s willingness to pay for forest insect control programs that reduce insect-related damage to non-market forest ecosystem services are reviewed in Rosenberger et al. (2012). New and promising areas of research extending non-market valuation methods to the suite of ecosystem services provided by natural areas are discussed in Charles and Dukes (2007) and Boyd et al. (2013). Two key examples of revealed preference techniques include hedonic pricing models and travel costs methods. Hedonic price studies look at the effect of an invasion on the value or market price of a closely related good—most often housing prices. Travel cost methods use expenditures people incur to visit a location (most often a recreation site) as a proxy for willingness to pay for that visit. Olden and Tamayo (2014), for example, used a hedonic model to measure damages from Eurasian milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) in King County, WA. They found the presence of Eurasian milfoil decreases the value of homes near invaded lakes by $94,000, or about 14%. Using similar methods, Horsch and Lewis (2009) found Eurasian milfoil decreases home values by about 13% on invaded lakes in Wisconsin. Nunes and van den Bergh (2004) used travel cost methods to measure the impact of algal blooms caused by non-native species along Dutch beaches. They found management actions required to reduce algal blooms would be worth about 225 million euros to area residents and visitors.

Information Needs of Various Types of Impact Studies

The assessment of economic impacts from non-native invasive species often initiates from qualitative estimates based on expert judgments (Brunel et al. 2009; Sansford 2002; Soliman et al. 2010). Expert judgments are used because of very low costs and availability of expert knowledge, but often lack transparency and rigor (Sansford 2002). From there, the application of partial budgeting, partial equilibrium, input-output analysis, and CGE is often dictated by the goal of the study, the methodology used, and the level of detail available (see Dixon and Parmenter 1996; Holland 2007; Miller and Blair 1985). Partial budgeting is better suited to estimate immediate impacts of invasive species introductions, whereas partial equilibrium models can provide insights on the changes in the production volumes and effects on commodity prices that may be affected by the introductions. Partial equilibrium models can also include many sectors so that the spillover effects between sectors can be analyzed. This method, however, requires defining the structure of the affected markets and the level of homogeneity for products from exogenous markets, and may require large amounts of data (Baker et al. 2009; Rich et al. 2005). If nationwide economic impacts or multi-sectorial effects are expected, then input-output analysis or CGE would be an appropriate choice because they each recognize the feedback loops that exist within the economy and address behavioral complexities that many of the other methods cannot deal with. However, input-output analysis and CGE also require a large amount of data and computational expertise.

14.4 Optimal Policies and Strategies

Biological invasions usually proceed in stages where each stage is associated with one or more management actions and a vector of economic costs and damages (Fig. 14.1). Economic analysis proceeds by seeking efficient strategies either within a stage (partial analysis) or across stages (global analysis). This section identifies research on prevention and control strategies, as well as factors such as risk and uncertainty that make designing an optimal policy extremely difficult.

Stages of invasion and associated management activities (from Holmes et al. 2014). Ecological sciences generally focus on species’ arrival, establishment, spread, and ecological impacts, which are affected by management actions. Management actions determine economic outcomes, and economic values should inform management decisions

Preventing Arrival and Introduction

Prevention policies focus on trade vectors and optimal inspection rates and must balance costs of policy, risk of introduction, and gains from trade (Chen et al. 2018; Leung et al. 2002; McAusland and Costello 2004). International trade is the major pathway for the introduction of non-native forest pests (Liebhold et al. 1995), and the importation of live plants is the most probable pathway of introduction for most damaging forest insects and pathogens established in the United States (Liebhold et al. 2012). Wood packing materials are the most common pathway of introduction for wood-boring forest insects, and the rapid acceleration in the use of these materials over the past decade is an increasing concern (Aukema et al. 2010; Strutt et al. 2013).

A general economic strategy for preventing the introduction of invasive species is to internalize the costs of biological invasions using tariffs in combination with improved port inspections (Perrings et al. 2005). Economic optimization suggests that the importing country should set the tariff equal to the sum of expected damages from contaminated units not detected during inspections plus the costs of inspections (McAusland and Costello 2004). When it is possible to estimate the probability of a successful invasion, each biosecurity facility should optimally set the marginal cost of undertaking preventive measures equal to marginal expected benefits (damages avoided), taking into account the probability that a species might invade through a different facility (Horan et al. 2002).

Inspection of shipments at ports of entry is one approach to reduce the introduction of invasive pests. For example, inspection of live plant imports is a prominent component of the system used by the US Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA APHIS) Plant Protection and Quarantine program to protect US agriculture and natural resources from unwanted and damaging pests (Venette et al. 2002). Inspectors examine a number of selected plant units from each incoming shipment. If a regulated pest or pathogen is detected in the sample units, inspectors may require that the shipment be treated, returned, or destroyed. Inspection strategies have been developed to allocate a fixed inspection budget among shipments to minimize the expected number or cost of accepted infested shipments (Springborn 2014; Surkov et al. 2009). Alternatively, the inspection budget can be allocated among shipments to minimize the expected number or cost of infested plant units in accepted shipments (slippage) (Chen et al. 2018; Yamamura et al. 2016). Sampling strategies that minimize expected slippage instruct inspectors to focus on larger shipments with higher plant infestation rates, while strategies that minimize the number of accepted infested shipments allocate sampling effort to shipments with higher infestation rates with less regard to shipment size. For live plant import inspections, optimization, based on the number of accepted infested plants, is most relevant because the number of introductions of a pest into the environment is a key predictor of establishment.

Most of the analysis on trade focuses on international imports and trade with foreign partners. However, of the 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species listed in the Global Invasive Species Database (Lowe et al. 2000), 86 species have already been introduced to the United States or are increasing their range within the United States, 7 species are indigenous or non-threatening to other areas of the United States, and only 7 species have not been introduced. Surprisingly, few studies acknowledge how this change in perspective has affected optimal policies and methods for measuring impacts. Warziniack et al. (2013), for example, demonstrated that correcting the externality with a tax on the risky vector is virtually impossible when hitchhiking species are linked to tourism and the incidence of private and recreational vehicles coming into the area.

Surveillance and Eradication to Prevent Establishment

The probability of successful establishment depends on the frequency and size of arrivals (propagule pressure), spatial habitat suitability, and temporal environmental fluctuations (Leung et al. 2004; Von Holle and Simberloff 2005), all of which are highly uncertain. Most preventative strategies are based on reducing propagule pressure, which is a measure of the expected number of individuals (e.g., the number of fecund adults of the species of interest) reaching an uninvaded location and is commonly expressed in terms of the rate, probability, or likelihood of arrival (Johnston et al. 2009; Simberloff 2009). However, if new species are repeatedly introduced through similar or novel invasion pathways, Allee effects and stochastic population dynamics are much less likely to cause initial populations to go extinct, thereby increasing the likelihood that isolated populations become established.Footnote 1

Surveillance systems designed to detect newly established species that evade port inspections are critical to reducing the potential for ecological and economic damage (Lodge et al. 2006). Cost-effective surveillance systems for newly established populations balance the intensity and cost of surveillance (which increase with the level of effort) with the costs of damage and eradication of newly detected populations (which may be less if detected early) (Epanchin-Niell and Hastings 2010). Economic models that account for this trade-off have assumed the pest location is unknown (Mehta et al. 2007); rates of pest establishment, spread, and damage vary across locales (Epanchin-Niell et al. 2012, 2014); small invasive populations establish ahead of an advancing front (Homans and Horie 2011); or that the likelihood of detection increases with the size of an infestation (Bogich et al. 2008). Research efforts have also focused on the properties of optimal one-time surveillance across multiple sites when species’ presence is uncertain prior to detection, accounting for heterogeneity in species occurrence, probability, and detectability across sites (Hauser and McCarthy 2009). Other models of one-time surveillance have investigated the impact of uncertainty regarding the extent (rather than simply the presence) of an infestation (Horie et al. 2013) and to maximize the coverage of the locations from where an invasive species is likely to spread to the uninvaded area (Yemshanov et al. 2015).

Economic models of long-term surveillance programs with constant surveillance effort have been developed using optimization algorithms and indicate that greater surveillance effort is warranted in locations that have higher establishment rates, higher damage and eradication costs, or lower sampling costs (Epanchin-Niell et al. 2012, 2014). In applying their model to the design of an optimal surveillance program for gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar dispar) detection and eradication in California, Epanchin-Niell et al. (2012) found that California’s 2010 county-level trapping densities correspond closely to the optimal trapping policy derived from the model; however, reductions in trapping densities in just 3 counties (out of 58 counties) might reduce long-term costs of surveillance and eradication in California by up to 30%. Using optimal control theory to calculate time-dependent surveillance policies that minimize the total cost of sampling, eradication, and damage by an invasive, Holden et al. (2016) developed rules of thumb to determine when intense initial sampling, followed by a sharp decrease in sampling effort, is more cost-effective than strategies that are constant through time. For invaders with high rates of establishment from an outside source, constant effort surveillance strategies are cost-effective. However, when reintroductions are infrequent, an intense early search for the invader can drastically reduce costs, depending on initial pest prevalence and the economic benefit-to-cost ratio of sampling.

Active research is currently underway to develop optimal surveillance and eradication policies when there is uncertainty about invasion dynamics and detectability. This line of research recognizes that surveillance may not provide accurate information, and therefore researchers have used partially observable Markov decision processes to address optimal invasive species surveillance (Regan et al. 2007), monitoring, and control strategies (Haight and Polasky 2010). More generally, partially observable decision models have been used to allocate management resources for networks of cryptic diseases, pests, and threatened species (Chadès et al. 2011).

Optimal Control to Slow the Spread

When a non-native species becomes established, various strategies can be used to reduce the expansion of its range, including initiating a domestic quarantine to reduce the chances of accidental movement of organisms to uninfested areas, detecting and eradicating isolated colonies, or applying control treatments to slow or stop the spread of the core population. Research has focused on developing optimal control strategies for slowing or eradicating populations and addressing questions such as when, where, and how much control should be applied (see Epanchin-Niell and Hastings 2010 for a review).

Invasive species control models generally include pest population dynamics and a stated objective of minimizing the sum of discounted control costs and invasion damages over time. The most basic models of invasive species dynamics focus on the numbers of individuals or the area of infestation and ignore spatial description (Eiswerth and Johnson 2002; Saphores and Shogren 2005; Sharov and Liebhold 1998). A general principle emerging from this research is that, if the invasive species stock is initially greater than its optimal equilibrium level, the highest level of management effort should be applied initially, and then should decline over time until the steady state is reached (Eiswerth and Johnson 2002). When the goal is to control the population front, the optimal strategy changes from eradication to slowing the spread to doing nothing; as the initial area occupied by the species increases, the negative impact of the pest per unit area decreases or the discount rate increases. Preventing population spread is not viewed as an optimal strategy unless natural barriers to population spread exist (e.g., Sharov and Liebhold 1998). These basic population models have been extended to account for uncertainty in invasion growth. The optimal control strategy is obtained using discrete-time stochastic dynamic programming (Eiswerth and van Kooten 2002; Olson and Roy 2002) or a real options framework in continuous time (Marten and Moore 2011; Saphores and Shogren 2005).

Policy is also complicated by politics—the political scales of policies rarely match the ecological scales of invasions. Effective management depends in part on coordination across jurisdictions, heterogeneous landscapes, heterogeneous populations (Epanchin-Niell et al. 2012), and international borders (Gren et al. 2010; Knowler and Barbier 2005; Tu et al. 2005). When bio-invasions occur at landscape scales and with multiple landowners, each landowner’s control decisions can impact their neighbors’ decisions by affecting invasion spread across boundaries (Epanchin-Niell et al. 2010; Epanchin-Niell and Wilen 2015; Wilen 2007). When landholders make control decisions based only on damages occurring on their own land, an externality occurs because those landholders taking action confer uncompensated benefits to those in advance of the invading front (Wilen 2007). As a result, managers may under-control from a systemwide perspective, leading to increased invasion of the landscape (Wilen 2007). Decision makers responsible for controlling a bio-invasion can internalize this diffusion externality and increase total net benefits across ownerships (e.g., Bhat and Huffaker 2007; Feder and Regev 1975; Richards et al. 2010; Sims et al. 2010).

Recently, spatially explicit models of invasive species dynamics and control have been developed for invasive plants (Blackwood et al. 2010; Büyüktahtakın et al. 2015), reptiles (Kaiser and Burnett 2010), insects (Sims et al. 2010; Kovacs et al. 2014), and generic pests (Epanchin-Niell and Wilen 2012; Hof 1998). All of the aforementioned models define the landscape as a set of discrete patches or map cells, define control activities for each patch, and predict the growth and dispersal of the invasive species among patches as a function of the selected controls. Spatial-dynamic models use a variety of models of pest population dynamics, including pest occupancy (Epanchin-Niell and Wilen 2012), pest population size (Blackwood et al. 2010; Büyüktahtakın et al. 2015; Hof 1998; Kaiser and Burnett 2010), and host and pest population sizes (Kovacs et al. 2014; Sims et al. 2010), depending on the characteristics of the ecological system.

Although these spatial-dynamic models are complicated to solve, they can provide pragmatic guidance to forest managers. For example, Kovacs et al. (2014) developed a spatial-dynamic model for the optimal control of EAB in the Twin Cities metropolitan area of Minnesota. They focused on managing valuable host trees by applying preventative insecticide treatment or pre-emptively removing infested trees to slow EAB spread. The model incorporates spatial variation in the ownership and benefits of host trees, the costs of management, and the budgets of municipal jurisdictions. The authors developed and evaluated centralized strategies for 17 jurisdictions surrounding the infestation. The central planner determines the quantities of trees in public ownership to treat and remove over time to maximize benefits associated with net costs of managing surviving trees across public and private ownerships, subject to constraints on municipal budgets, management activities, and access to private trees. The results suggest that centralizing the budget across jurisdictions, rather than increasing any one municipal budget, does more to increase total net benefits. Further, strategies incorporating insecticide treatments are superior to those with pre-emptive removal because they reduce the quantity of susceptible trees at lower cost and protect the benefits of healthy trees. Finally, increasing the accessibility of private trees to public management substantially slows EAB spread and improves total net benefits. The change from local to centralized control increased the percentage of healthy trees remaining on the landscape by 18% and more than doubled the total net benefits.

Much of the literature on invasive species management in multi-ownership landscapes examines two polar cases characterizing control choices. In the first case, myopic landowners choose their own control without considering the impact of their choices on the probability that other landowners’ at-risk lands will become infested. In the second case, a social planner is assumed to control actions for landowners at a landscape level, thus internalizing all externalities by choosing controls that maximize social welfare. Epanchin-Niell and Wilen (2015) point out that this dichotomy fails to capture the often-observed case in which landowners cooperate with other managers to control the spread of an invasive species by engaging in an invasive species cooperative control district. The classical way to boost cooperation has been addressed in the economics literature is through a bargaining mechanism such as a transfer payment. For example, Cobourn et al. (2016) developed a theory of cooperation for invasive species management using an axiomatic Nash bargaining game assuming that the threat exists for an invasive species to spread from an infested to an uninfested municipality. Without bargaining, the infested municipality chooses control efforts that maximize its own benefits and likely invests too little from a social perspective because its choice of control influences the probability that the invasive species will spread to the uninfested municipality. Therein lies the potential for bargaining: the uninfested municipality has an incentive to bargain with the infested municipality to share in the latter’s control costs, using a transfer payment in exchange for applying a higher level of control that would effectively reduce the probability that the invasive species will spread. Cobourn et al. (2016) calibrate their bargaining model to represent the emerald ash borer invasion in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, MN. Their results suggest that bargaining improves the public benefits across communities relative to the case without bargaining. Further, bargaining may achieve the social planner’s optimal level of control when the uninfested municipality possesses a substantial advantage in terms of relative bargaining power. Short-term bargaining agreements are unlikely to succeed, suggesting that there may be a role for a higher government involvement to facilitate long-term bargaining agreements.

In many situations, land managers specify a desired outcome in terms of ecosystem attributes, such as species composition, vegetation structure, pest population size, or likelihood of pest occurrence, striving for a management strategy that achieves these attributes at least cost. A manager may have many mutually exclusive least-cost projects to select for investment given a limited budget. Conservation priorities are generally made with an eye solely on benefits of management actions, largely ignoring costs (Brooks et al. 2006; Groves et al. 2002). A more thorough (and efficient) method would use return-on-investment (ROI) as a decision criterion for prioritizing projects, making use of both benefit and cost data. As discussed in Polasky (2008), a number of studies have shown that, for a wide range of conservation objectives, more variability exists in costs of land management options than exists in the ecological benefits. Bode et al. (2008), for example, used seven different taxonomic measures of biodiversity to allocate funding among 34 of the world’s terrestrial biodiversity hotspots with the objective of minimizing total species loss. They found the optimal decision was far less dependent on the measure of biodiversity than it was on cost of conservation. Similar studies using ROI as a decision criterion have been conducted for ecological restoration in Hawaii (Goldstein et al. 2008), temperate forests in North America and Mediterranean ecoregions (Murdoch et al. 2007), and Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub (Underwood et al. 2008). The ROI criterion could be used as a decision criterion for prioritizing invasive species management projects.

Optimal Control and Risk Across Invasion Stages

Economic models that focus on a single stage of the invasion process cannot provide globally optimal solutions because they ignore potential trade-offs among defensive actions across the stages of an invasion. Optimal allocation among prevention and control depends on the nature of prevention and control cost curves and the decision maker’s preferences over risky events. Research has shown that, under some conditions, invasive species can be managed most cost-effectively using greater investments in prevention relative to control because damages can be catastrophic (Leung et al. 2002). Other research has shown that, if decision makers are risk averse and if control options are thought to be more certain than prevention, then control may be preferred to prevention (Finnoff et al. 2007). Recent innovations in the analysis of trade-offs among invasion stages include the development of spatial models of prevention, detection, and control (Sanchirico et al. 2010). Such interdependencies between prevention and control are highlighted in Burnett et al. (2006), with examples from Hawaii for both a current invader (miconia, Miconia calvescens) and a potential invader (brown tree snake, Boiga irregularis). The primary lesson is that focusing on a subset of transmission pathways, on only one or two controls, or on a single region ignores important interactions that are critical in identifying cost-effective policy recommendations.

Investments in prevention should also be made recognizing the ability to detect the invader in the environment and the ability to control or eradicate it should it become established (Haight and Polasky 2010; Mehta et al. 2007). Studies such as Homans and Horie (2011) and Epanchin-Niell et al. (2014) consider optimal control decisions post detection when determining optimal levels of investment in surveillance.

Special methods have also been introduced to develop optimal policies to manage invasive species in the presence of uncertainty (Eiswerth and Johnson 2002; Haight and Polasky 2010; Hester and Cacho 2012; Horie et al. 2013; Hyytiainen et al. 2013; Olson and Roy 2002). Adding the dimensions of risk and uncertainty requires that decision makers consider their perceptions of risk, such as risk aversion (Olson and Roy 2005). Often, risk of invasion is treated in optimal management policies as exogenous (Leung et al. 2002; Ranjan et al. 2008), with fewer attempts to represent the risk of invasion as endogenous (Finnoff and Shogren 2004).

14.5 Gaps and Future Research Needs

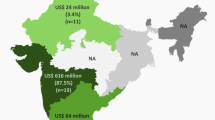

Invasive species science has largely remained in the domain of natural sciences. Greater research in economics and other social sciences could help to better integrate governance and management policy, address the objectives of multiple stakeholders, account for risk perceptions, and promote bargaining and cooperative behavior among decision makers. To date, there has not been a comprehensive investigation of impacts from terrestrial and aquatic invasive species, including the full value of ecosystem services lost. Acquiring such data is necessary for conducting cost-benefit analyses. This omission prevents policymakers from establishing a meaningful list of priorities and realistic management strategies. Table 14.1 gives a few representative damage estimates from the literature, focusing primarily on local and regional studies. Estimates of damages from invasive species at national (or even global) scales usually combine values from several studies or generalize across diverse landscapes, invaders, and impact methods. While the large impact numbers such studies generate are popular with policymakers and scientists looking to emphasize the importance of their research problem, they violate some of the most basic rules of economic analysis and generally do more harm than good to the science.

Uncertainty about invasive species remains a serious challenge in the development of effective control and management policies, and will require special analytic and modeling tools to factor uncertainty into optimal management policies. Another important issue that remains to be addressed is the practical validation of optimal management policies that have been developed. While many countries have introduced strategies to reduce the rates of non-native species introductions, such as sanitary and phytosanitary policies that regulate the movement of pest-associated commodities, more efforts will be required to assess the practical utility and transaction costs of implementing those measures.

14.6 Key Findings

-

Changes in trade and phytosanitary practices have altered the relative risk of species introductions and the importance of particular pathways. Introductions of wood-borers increased faster than any other insect guild since the 1980s due to the increased volume of containerized freight and accompanying wood packaging material (Aukema et al. 2010).

-

For live plant import inspections, optimizing based on the number of accepted infested plants is most relevant because the number of introductions of a pest into the environment is a key predictor of establishment. This optimization results in strategies that allocate limited sampling resources to larger shipments that have higher infestation rates (Chen et al. 2018).

-

For invaders with high rates of establishment from an outside source, constant effort surveillance strategies are cost-effective (Epanchin-Niell et al. 2012, 2014). However, when reintroductions are infrequent, an intense early search for the invader can drastically reduce costs, depending on initial pest prevalence and the economic benefit-to-cost ratio of sampling (Holden et al. 2016).

-

When landholders make control decisions based only on damages occurring on their own land, an externality occurs because controllers confer uncompensated benefits to those in advance of the invading front (Epanchin-Niell and Wilen 2015). This externality creates an incentive for landowners to cooperate in the cross-boundary control of invading populations. One mechanism for furthering cooperation is bargaining for a transfer payment from an invasion-free landowner to fund increased control by an invaded landowner (Cobourn et al. 2016).

14.7 Key Information Needs

-

Expanding applications of non-market valuation methods to address the suite of ecosystem services provided by natural areas that are at risk because of invasive species would facilitate more comprehensive cost-benefit analyses.

-

Developing models that account for cooperative management among landowners and across policy jurisdictions would help to address behavioral interactions among landowners and jurisdictions.

-

Conservation priorities are often determined solely on the basis of the benefits of proposed management actions, not including costs. A more thorough analysis, such as ROI, would employ both benefit and cost data, when decision criterion for prioritizing projects is desired.

-

Economic models that focus on a single stage of the invasion process cannot provide globally optimal solutions because they ignore potential trade-offs among defensive actions across the stages of an invasion. Ideally, economic models should consider such trade-offs to provide a fuller accounting of invasion economic effects.

-

Effective control and management depends on model improvement to account for uncertainty surrounding impacts and the probability of introductions.

-

Additional studies are needed to investigate the spread of invasive species through domestic trade, and how policies may differ between foreign and domestic sources of risk.

Disclaimer Text

The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy.

Notes

- 1.

An Allee effect, as defined by Drake and Kramer (2011), “is a positive association between absolute average individual fitness and population size over some finite interval.” In some cases, Allee effects imply a minimum population size necessary for a species to become established.

Literature Cited

Anderson AM, Shwiff SS, Shwiff SA (2014) Economic impact of the potential spread of vampire bats into South Texas. USDA National Wildlife Research Center – Staff Publications. 1762

Arthur M (2006) An economic analysis of quarantine: the economics of Australian’s ban on New Zealand apple imports. In: Proceedings of the New Zealand agricultural and resource economics society annual conference, Nelson. 2425

Aukema JE, McCullough DG, Von Holle B et al (2010) Historical accumulation of nonindigenous forest pests in the continental United States. Bioscience 60(11):886–897

Aukema JE, Leung B, Kovacs K et al (2011) Economic impacts of non-native forest insects in the continental United States. PLoS One 6(9):e24587

Bain MB, Cornwell ER, Hope KM et al (2010) Distribution of an invasive aquatic pathogen (viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus) in the Great Lakes and its relationship to shipping. PLoS One 5:e10156

Baker HG (1986) Patterns of plant invasion in North America. In: Ecology of biological invasions of North America and Hawaii. Springer, New York, pp 44–57

Baker RHA, Battisti A, Bremmer J et al (2009) PRATIQUE: a research project to enhance pest risk analysis techniques in the European Union. EPPO Bull 39:87–93

Banks NC, Paini DR, Bayliss KL, Hodda M (2015) The role of global trade and transport network topology in human-mediated dispersal of alien species. Ecol Lett 18:188–199

Barber LM, Schleier JJ, Peterson RKD (2010) Economic cost analysis of West Nile virus outbreak, Sacramento County, California, USA, 2005. Emerg Infect Dis 16(3):480–486

Barlow L-A, Cecile J, Bauch CT, Anand M (2014) Modelling interactions between forest pest invasions and human decisions regarding firewood transport restrictions. PLoS One 9:e90511

Bhat MG, Huffaker RG (2007) Management of a transboundary wildlife population: a self-enforcing cooperative agreement with renegotiation and variable transfer payments. J Environ Econ Manag 53(1):54–67

Binder S, Haight RG, Polasky S et al (2016) Assessment and valuation of forest ecosystem services: state of the science review, Gen. Tech. Rep. NRS-170. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Northern Research Station, pp 1–47

Blackwood J, Hastings A, Costello C (2010) Cost-effective management of invasive species using linear-quadratic control. Ecol Econ 69:519–527

Blakeslee AMH, McKenzie CH, Darling JA et al (2010) A hitchhiker’s guide to the Maritimes: anthropogenic transport facilitates long-distance dispersal of an invasive marine crab to Newfoundland. Divers Distrib 16:879–891

Bode M, Wilson KA, Brooks TM et al (2008) Cost-effective global conservation spending is robust to taxonomic group. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105(17):6498–6501

Bogich TL, Liebhold AM, Shea K (2008) To sample or eradicate? A cost minimization model for monitoring and managing an invasive species. Journal of Applied Ecology 45:1134–1142

Bossenbroek JM, Finnoff DC, Shogren JF, Warziniack TW (2009) Advances in ecological and economic analyses of invasive species: dreissenid mussels as a case study. In: Bioeconomics of invasive species: integrating ecology, economics, policy, and management. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 244–265

Boyd IL, Freer-Smith PH, Gilligan CA, Godfray HCJ (2013) The consequences of tree pests and diseases for ecosystem services. Science 342:1235773

Brawley SH, Coyer JA, Blakeslee AMH et al (2009) Historical invasions of the intertidal zone of Atlantic North America associated with distinctive patterns of trade and emigration. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106:8239–8244

Breukers A, Mourits M, van der Werf W, Lansink OA (2008) Costs and benefits of controlling quarantine diseases: a bio-economic modeling approach. Agric Econ 38:137–149

Brooks TM, Mittermeier RA, da Fonseca GAB et al (2006) Global biodiversity conservation priorities. Science 313(5783):58–61

Brunel S, Petter F, Fernandez-Galiano E, Smith I (2009) Approach of the European and Mediterranean plant protection organization to the evaluation and management of risks presented by invasive alien plants. In: Inderjit (ed) Management of invasive weeds. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 319–343

Burnett K, Kaiser B, Pitafi BA, Roumasset J (2006) Prevention, eradication, and containment of invasive species: illustrations from Hawaii. Agric Resour Econ Rev 35(1):63

Büyüktahtakın IE, Kibis EY, Cobuloglu HI et al (2015) An age-structured bio-economic model of invasive species management: insights and strategies for optimal control. Biol Invasions 17:2545–2563

Chadès I, Martin TG, Nicol S et al (2011) General rules for managing and surveying networks of pests, diseases, and endangered species. Proc Natl Acad U S A 108(20):8323–8328

Charles H, Dukes JS (2007) Impacts of invasive species on ecosystem services. In: Biological invasions. Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg, pp 217–237

Chen C, Epanchin-Niell RS, Haight RG (2018) Optimal inspection of imports to prevent invasive pest introduction. Risk Anal 38(3):603–619

Chivers C, Leung B (2012) Predicting invasions: alternative models of human-mediated dispersal and interactions between dispersal network structure and Allee effects. J Appl Ecol 49:1113–1123

Cobourn KM, Amacher GS, Haight RG (2016) Cooperative management of invasive species: a dynamic Nash bargaining approach. Environ Resour Econ:1–28

Cook DC (2008) Benefit cost analysis of an import access request. Food Policy 33(3):277–285

Cozzens T, Gebhardt K, Shwiff S et al (2010) Modeling the economic impact of feral swine-transmitted foot-and-mouth disease: a case study from Missouri. In: Timm RM, Fagerston KA (eds) Vertebrate pest conference. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/wildlife_damage/nwrc/publications/10pubs/cozzens101.pdf

Davidson AD, Hewitt CL, Kashian DR (2015) Understanding acceptable level of risk: incorporating the economic cost of under-managing invasive species. PLoS One 10(11):e0141958

Dixon PB, Parmenter BR (1996) Computable general equilibrium modeling for policy analysis and forecasting. In: Amman HM, Kendrick DA, Rust J (eds) Handbook of computational economics, vol I. Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam

Drake JM, Kramer AM (2011) Allee effects. Nat Educ Knowl 3(10):2. http://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/allee-effects-19699394

Drake JM, Lodge DM (2007) Hull fouling is a risk factor for intercontinental species exchange in aquatic ecosystems. Aquat Invasions 2(2):121–131

Eiswerth ME, Johnson WS (2002) Managing nonnative invasive species: insights from dynamic analysis. Environ Resour Econ 23(3):319–342

Eiswerth ME, van Kooten GC (2002) Uncertainty, economics, and the spread of an invasive plant species. Am J Agric Econ 84(5):1317–1322

Elliston L, Hinde R, Yainshet A (2005) Plant disease incursion management. In: International workshop on multi-agent systems and agent-based simulation. Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg, pp 225–235

Elser JL, Anderson A, Lindell CA, Dalsted N, Bernasek A, Shwiff SA (2016) Economic Impacts of bird damage and management in U.S. Sweet Cherry production. Crop Production. Elsivier. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.croppro.2016.01.014

Elobeld A, Beghin J (2006) Multilateral trade and agricultural policy reforms in sugar markets. J Agric Econ 57(1):23–48

Epanchin-Niell RS, Hastings A (2010) Controlling established invaders: integrating economics and spread dynamics to determine optimal management. Ecol Lett 13(4):528–541

Epanchin-Niell RS, Wilen JE (2012) Optimal spatial control of biological invasions. J Environ Econ Manag 63:260–270

Epanchin-Niell RS, Wilen JE (2015) Individual and cooperative management of invasive species in human-mediated landscapes. Am J Agric Econ 97:180–198

Epanchin-Niell RS, Hufford MB, Aslan CE et al (2010) Controlling invasive species in complex social landscapes. Front Ecol Environ 8:210–216

Epanchin-Niell RS, Haight RG, Berec L et al (2012) Optimal surveillance and eradication of invasive species in heterogeneous landscapes. Ecol Lett 15(8):803–812

Epanchin-Niell R, Brockerhoff E, Kean J, Turner J (2014) Designing cost-efficient surveillance for early detection and control of multiple biological invaders. Ecol Appl 24:1258–1274

Fagiolo G, Reyes R, Schiavo S (2010) The evolution of the world trade web: a weighted-network analysis. J Evol Econ 20:479–514

FAO IPPC (2004) Pest risk analysis for quarantine pests including analysis of environmental risks. International standards for phytosanitary measures, Publication No. 11. Rev. 1. FAO, Rome

Feder G, Regev U (1975) Biological interactions and environmental effects in the economics of pest control. J Environ Econ Manag 2:75–91

Finnoff D, Shogren JF (2004) Endogenous risk as a tool for nonindigenous species management. Weed Control 18:1261–1265

Finnoff D, Shogren JF, Leung B, Lodge D (2005) The importance of bioeconomic feedback in invasive species management. Ecol Econ 52(3):367–381

Finnoff D, Shogren JF, Leung B, Lodge D (2007) Take a risk: preferring prevention over control of biological invaders. Ecol Econ 62(2):216–222

Finnoff D, McIntosh C, Shogren JF et al (2010) Invasive species and endogenous risk. Ann Rev Resour Econ 2(1):77–100

Fraser R, Cook D (2008) Trade and invasive species risk mitigation: reconciling WTO compliance with maximising the gains from trade. Food Policy 33(2):176–184

Goldstein JH, Pejchar L, Daily GC (2008) Using return-on-investment to guide restoration: a case study from Hawaii. Conserv Lett 1(5):236–243

Great Lakes Commission, & St. Lawrence Cities Initiative (2012) Restoring the natural divide: separating the Great Lakes and Mississippi River basins in the Chicago Area waterway system. http://projects.glc.org/caws//pdf/CAWS-PublicSummary-mediumres.pdf

Gren I-M, Thierfelder T, Berglund H (2010) Country characteristics and non-indigenous species. Environ Dev Econ 18:51–70

Groves CR, Jensen DB, Valutis LL et al (2002) Planning for biodiversity conservation: putting conservation science into practice a seven-step framework for developing regional plans to conserve biological diversity, based upon principles of conservation biology and ecology, is being used extensively by the nature conservancy to identify priority areas for conservation. Bioscience 52(6):499–512

Haight RG, Polasky S (2010) Optimal control of an invasive species with imperfect information about the level of infestation. Resour Energy Econ 32(4):519–533

Hauser C, McCarthy M (2009) Streamlining ‘search and destroy’: cost-effective surveillance for invasive species management. Ecol Lett 12:683–692

Hester S, Cacho O (2012) Optimization of search strategies in managing biological invasions: a simulation approach. Hum Ecol Risk Assess Int J 18:181–199

Hirsch SA, Leitch JA (1996) The impact of knapweed on Montana’s economy agricultural economics report February, 355. http://mtweed.org/wp-content/uploads/impact-of-knapweed-mt-economy.pdf

Hof J (1998) Optimizing spatial and dynamic population-based control strategies for invading forest pests. Nat Resour Model 11(3):197–216

Holden MH, Nyrop JP, Ellner SP (2016) The economic benefit of time-varying surveillance effort for invasive species management. J Appl Ecol 53(3):712–721

Holland J (2007) Tools for institutional, political, and social analysis of policy reform. A source book for development practitioners. The World Bank/Oxford University Press, Washington, DC

Holmes TP (1991) Price and welfare effects of catastrophic forest damage from southern pine beetle epidemics. For Sci 37(2):500–516

Holmes TP, Aukema J, Englin J et al (2014) Economic analysis of biological invasions in forests. In: Kant S, Alavalapati J (eds) Handbook of forest resource economics. Routledge, New York, p 560

Homans F, Horie T (2011) Optimal detection strategies for an established invasive pest. Ecol Econ 70:1129–1138

Horan RD, Perrings C, Lupi F, Bulte E (2002) Biological pollution prevention strategies under ignorance: the case of invasive species. Am J Agric Econ 84(5):1303–1310

Horie T, Haight RG, Homans FR, Venette R (2013) Optimal strategies for the surveillance and control of forest pathogens. Ecol Econ 86:78–85

Horsch EJ, Lewis DJ (2009) The effects of aquatic invasive species on property values: evidence from a quasi-experiment. Land Econ 85(3):391–409

Hulme PE (2009) Trade, transport and trouble: managing invasive species pathways in an era of globalization. J Appl Ecol 46:10–18

Hulme PE, Bacher S, Kenis M et al (2008) Grasping at the routes of biological invasions: a framework for integrating pathways into policy. J Appl Ecol 45:403–414

Hyytiäinen K, Lehtniemi M, Niemi JK, Tikka K (2013) An optimization framework for addressing aquatic invasive species. Ecol Econ 91:69–79

International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) (2002) Guidelines for regulating wood packaging material in international trade. Secretariat of the international plant protection convention. FAO, Rome. https://www.ippc.int/servlet/BinaryDownloaderServlet/16259_ISPM_15_English.pdf?filename=1055161712885_ISPM15_e.pdf&refID=16259

Jacobi WR, Goodrich BA, Cleaver CM (2011) Firewood transport by national and state park campers: a risk for native or exotic tree pest movement. Arboricult Urban For 37:126–138

Johnston EL, Piola RF, Clark GF (2009) The role of propagule pressure in invasion success. In: Rilov G, Crooks JA (eds) Biological invasions in marine ecosystems. Ecological studies (Analysis and synthesis), vol 204. Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg

Juliá R, Holland DW, Guenthner J (eds) (2007) Assessing the economic impact of invasive species: the case of yellow starthistle (Centaurea solsitialis L.) in the rangelands of Idaho, USA. J Environ Manag 85:876–882

Just RE, Rausser GC, Zilberman D (1982) Modeling equity and efficiency in agricultural production systems. Growth Equity Agric Dev:120–138

Kaiser BA (2006) Economic impacts of non-indigenous species: Miconia and the Hawaiian economy. Euphytica 148(1–2):135–150

Kaiser BA, Burnett KM (2010) Spatial economic analysis of early detection and rapid response strategies for an invasive species. Resour Energy Econ 32:566–585

Kaluza P, Kolzsch A, Gastner MT, Blasius B (2010) The complex network of global cargo ship movements. J R Soc Interface 7:1093–1103

Kaye-Blake WH, Saunders CM, Cagatay S (2008) Genetic modification technology and producer returns: the impacts of productivity, preferences, and technology uptake. Rev Agric Econ 30(4):692–710

Keller RP, Drake JM, Drew MB, Lodge DM (2011) Linking environmental conditions and ship movements to estimate invasive species transport across the global shipping network. Divers Distrib 17(1):93–102

Kinnunen RE (2015) Sea lamprey control in the Great Lakes, Michigan State University Extension Newsletter. http://msue.anr.msu.edu/news/sea_lamprey_control_in_the_great_lakes

Knowler D, Barbier E (2005) Importing exotic plants and the risk of invasion: are market-based instruments adequate? Ecol Econ 52(3):341–354

Koch FH, Yemshanov D, Magarey RD, Smith WD (2012) Dispersal of invasive forest insects via recreational firewood: a quantitative analysis. J Econ Entomol 105:438–450

Kovacs KF, Haight RG, McCullough DG et al (2010) Cost of potential emerald ash borer damage in US communities, 2009–2019. Ecol Econ 69:569–578

Kovacs K, Vaclavik T, Haight RC et al (2011) Prediction the economic costs and property value losses attributed to sudden oak death damage in California (2010–2020). J Environ Manag 92:1291–1302

Kovacs KF, Haight RG, Mercader RJ, McCullough DG (2014) A bioeconomic analysis of an emerald ash borer invasion of an urban forest with multiple jurisdictions. Resour Energy Econ 36(1):270–289

Leitch JA, Leistritz LF, Bangsund DA (1996) Economic effect of leafy spurge in the Upper Great Plains: methods, models, and results. Impact Assess 14(4):419–433

Leontief W (1986) Input–output economics. Oxford University Press, New York

Leung B, Lodge DM, Finnoff D et al (2002) An ounce of prevention or a pound of cure: bioeconomic risk analysis of invasive species. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 269(1508):2407–2413

Leung B, Drake JM, Lodge DM (2004) Predicting invasions: propagule pressure and the gravity of Allee effects. Ecology 85:1651–1660

Li X, Preisser EL, Boyle KJ et al (2014) Potential social and economic impacts of the hemlock woolly adelgid in southern New England. Southeastern Nat 13(sp6):130–146

Liebhold AM, Tobin PC (2008) Population ecology of insect invasions and their management. Annu Rev Entomol 53:387–408

Liebhold AM, Macdonald WL, Bergdahl D, Mastro VC (1995) Invasion by exotic forest pests: a threat to forest ecosystems. In: Forest science monograph. Society of American Foresters, Bethesda, p 30

Liebhold AM, Brockerhoff EG, Garrett LJ et al (2012) Live plant imports: the major pathway for forest insect and pathogen invasions of the US. Front Ecol Environ 10(3):135–143

Lodge DM, Williams S, MacIsaac HJ et al (2006) Biological invasions: recommendations for U.S. policy and management. Ecol Appl 16:2035–2054

Lounibos LP (2002) Invasions by insect vectors of human disease. Annu Rev Entomol 47:233–266

Lovett G, Weiss M, Liebhold A et al (2016) Non-native forest insects and pathogens in the US: impacts and policy options. Ecol Appl 26(5):1437–1455

Lowe S, Browne M, Boudjelas S, De Poorter M (2000) 100 of the world’s worst invasive alien species: a selection from the global invasive species database. https://www.iucn.org/content/100-worlds-worst-invasive-alien-species-selection-global-invasive-species-database

Mack RN (1991) The commercial seed trade: an early disperser of weeds in the United States. Econ Bot 45(2):257–273

Macleod A, Head J, Gaunt A (2003) The assessment of the potential economic impact of Thrips palmi on horticulture in England and the significance of a successful eradication campaign. Crop Prot 23:601–610

Marten AL, Moore CC (2011) An options based bioeconomic model for biological and chemical control of invasive species. Ecol Econ 70:2050–2061

Mas-Colell A, Whinston MD, Green JR (1995) Microeconomic theory. Oxford University Press, New York

McAusland C, Costello C (2004) Avoiding invasives: trade-related policies for controlling unintentional exotic species introductions. J Environ Econ Manag 48(2):954–977

McDermott SM, Finnoff DC, Shogren JF (2013) The welfare impacts of an invasive species: endogenous vs. exogenous price models. Ecol Econ 85:43–49

McNeely JA, Mooney HA, Neville LE et al (2001) A global strategy on invasive alien species. World Conservation Union (IUCN), Gland/Cambridge

Mehta SV, Haight RG, Homans FR et al (2007) Optimal detection and control strategies for invasive species management. Ecol Econ 61(2):237–245

Mérel PR, Carter CA (2008) A second look at managing import risk from invasive species. J Environ Econ Manag 56(3):286–290

Miller R, Blair P (1985) Input output analysis: foundations and extensions. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Murdoch W, Polasky S, Wilson KA et al (2007) Maximizing return on investment in conservation. Biol Conserv 139(3):375–388

Ninan KN (ed) (2014) Valuing ecosystem services: methodological issues and case studies. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Nunes PA, van den Bergh JC (2004) Can people value protection against invasive marine species? Evidence from a joint TC–CV survey in the Netherlands. Environ Resour Econ 28(4):517–532

Olden JD, Tamayo M (2014) Incentivizing the public to support invasive species management: Eurasian milfoil reduces lakefront property values. PLoS One 9(10):e110458

Olson LJ, Roy S (2002) The economics of controlling a stochastic biological invasion. Am J Agric Econ 84:1311–1316

Olson LJ, Roy S (2005) On prevention and control of an uncertain biological invasion. Rev Agric Econ 27:491–497

Payne BR, White WB, McCay RE, McNichols RR (1973) Economic analysis of the gypsy moth problem in the northeast: II. Applied to residential property, Res. Pap. NE-285. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, Upper Darby, 6 p

Perrings C, Dehnen-Schmutz K, Touza J, Williamson M (2005) How to manage biological invasions under globalization. Trends Ecol Evol 20:212–215

Piper B, Liu L (2014) Predicting the total economic impacts of invasive species: the case of the red streaked leafhopper. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2536457

Polasky S (2008) Why conservation planning needs socioeconomic data. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105(18):6505–6506

Pysek P, Jarošik V, Hulme PE et al (2010) Disentangling the role of environmental and human pressures on biological invasions across Europe. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107:12157–12162

Qaim M, Traxler G (2005) Roundup ready soybeans in Argentina: farm level and aggregate welfare effects. Agric Econ 32(1):73–86

Ranjan R, Marshall E, Shortle J (2008) Optimal renewable resource management in the presence of endogenous risk of invasion. J Environ Manag 89(4):273–283

Regan TJ, McCarthy MA, Baxter PWJ et al (2007) Optimal eradication: when to stop looking for an invasive plant. Ecol Lett 9(7):759–766

Reichard SH, White P (2001) Horticultural introductions of invasive plant species: a North American perspective in the great reshuffling. In: McNeeley JA (ed) Human dimensions of invasive species. IUCN, The World Conservation Union, Gland/Cambridge

Rich KM, Miller GY, Winter-Nilson A (2005) A review of economic tools for the assessment of animal disease outbreaks. Paris Sci Tech Rev Off Int Epizooties 24:833–845

Richards TJ, Ellsworth P, Tronstad R, Naranjo S (2010) Market-based instruments for the optimal control of invasive insect species: B. tabaci in Arizona. J Agric Resour Econ 35:349–367

Rosenberger RS, Bell LA, Champ PA, Smith EL (2012) Nonmarket economic values of forest insect pests: an updated literature review, Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS 275. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Fort Collins, 46 p

Rothlisberger JD, Finnoff DC, Cooke RM, Lodge DM (2012) Ship-borne nonindigenous species diminish Great Lakes ecosystem services. Ecosystems 15(3):1–15

Salaudeen T, Thomas M, Harding D, Hight SD (2013) Economic impact of tropical soda apple (Solanum viarum) on Florida cattle production. Weed Technol 27(2):389–394

Sanchirico JN, Albers HJ, Fischer C, Coleman C (2010) Spatial management of invasive species: pathways and policy options. Environ Resour Econ 45:517–535

Sansford C (2002) Quantitative versus qualitative: pest risk analysis in the UK and Europe including the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection (EPPO) system. NAPPO International Symposium on Pest Risk Analysis, Puerto Vallarta

Saphores J, Shogren J (2005) Managing exotic pests under uncertainty: optimal control actions and bioeconomic investigations. Ecol Econ 52:327–339

Schmidt JP, Springborn M, Drake JM (2012) Bioeconomic forecasting of invasive species by ecological syndrome. Ecosphere 3(5):1–19

Schmitz TG, Giese CR, Shultz CJ (2008) Welfare implications of EU enlargement under the CAP. Can J Agric Econ 56(4):555–562

Settle C, Shogren JF (2004) Hyperbolic discounting and time inconsistency in a native–exotic species conflict. Resour Energy Econ 26(2):255–274

Sharov AA, Liebhold AM (1998) Bioeconomics of managing the spread of exotic pest species with barrier zones. Ecol Appl 8(3):833–845

Shogren JF (2000) Risk reduction strategies against the ‘explosive invader’. In: The economics of biological invasions. E. Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 56–69

Shwiff SA, Gebhardt K, Kirkpatrick KN, Shwiff SS (2010) Potential economic damage from introduction of brown tree snakes Boiga irregularis (Reptilia: Colubridae), to the Islands of Hawai’i. Pac Sci 1:1–10

Simberloff D (2005) The politics of assessing risk for biological invasions: the USA as a case study. Trends Ecol Evol 20(5):216–222

Simberloff D (2009) The role of propagule pressure in biological invasions. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 40:81–102

Sims C, Aadland D, Finnoff D (2010) A dynamic bioeconomic analysis of mountain pine beetle epidemics. J Econ Dyn Control 34(12):2407–2419

Soliman T, Mourits MCM, Oude Lansink AGJM, van der Werf W (2010) Economic impact assessment in pest risk analysis. Crop Prot 29:517–524

Springborn MR (2014) Risk aversion and adaptive management: insights from a multi-armed bandit model of invasive species risk. J Environ Econ Manag 68(2):226–242

Strutt A, Turner JA, Haack RA, Olson L (2013) Evaluating the impacts of an international phytosanitary standard for wood packaging material: global and United States trade implications. Forest Policy Econ 27:54–64

Surkov IV, Oude Lansink AGJM, van der Werf W (2009) The optimal amount and allocation of sampling effort for plant health inspection. Eur Rev Agric Econ 36:295–320

Tatem AJ, Rogers DJ, Hay SI (2006) Global transport networks and infectious disease spread. Adv Parasitol 62:293–343

The Research Group, LLC (2014) Economic impact from selected noxious weeds in Oregon. Prepared for Oregon Department of Agricultural Noxious Weed Control Program

Tu A, Beghin J, Gozlan E (2005) Tariff escalation and invasive species risk; Working Paper 05-WP 407. Center for Agricultural and Rural Development: Iowa State University, Ames