Abstract

This chapter aims to provide the nurse, therapist and social care professional with confidence to quickly and effectively assess a newly encountered frail elderly patient in all settings. This is done by using a Frailty Approach, a recent and necessary paradigm for care of our ageing population. The key areas of Frailty, Dementia, Delirium, Polypharmacy, Co-morbidities and Falls are described.

Thereafter, the main tool for this approach is explained in detail—Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), which requires the input of a multidisciplinary team (MDT) to be effective. With its four domains—Medical, Social, Functional and Cognitive, CGA details a logical, timely and effective way of gaining the essentials of the patient’s presentation. A guide to summarising and recording this is given to enable appropriate care-planning and management tailored to the patient’s needs.

This is underpinned by a detailed case scenario, where we meet 92-year-old Violet. Violet’s fall and presentation to the emergency department illustrates the use of CGA to establish an accurate picture of her needs and how to go about effectively addressing them.

The chapter then describes suggestions for further learning in this broad and developing subject area, which is increasingly the focus for most health services across the world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

7.1 Learning Objectives

This chapter will enable you to:

-

Approach the complexity of elderly frail patients with confidence

-

Adopt a systematic approach to assessment of the older person

-

Quickly gain an accurate picture of your patient and their needs, to enable care-planning

7.2 Introduction

This chapter will address the complexity of older people’s presentations. To do this, Frailty will be clearly defined and its emergence as an important clinical syndrome and diagnosis explained. By illustrating a logical and evidenced approach, you will have the confidence to apply this knowledge, equipped with the skills you need to effectively support and manage the frail elderly patient. The Frailty Approach is appropriate to all settings, where the nurse, therapist, health or social care professional encounters the elderly patient, be it on the hospital ward, in the Emergency Department, the out-patient clinic, in nursing or residential homes, hospice or the patient’s own home.

Reflective Exercise

-

Why do you think it is important to have a knowledge and understanding of Frailty and its impact on older people?

7.2.1 A Frailty Approach

Every one of us has a life story, a context which helps us to appreciate, understand and engage with. This forms an important part of the comprehensive assessment of older people. My mum was a nurse in the new National Health Service (NHS), training in London from 1951 to 1954. She was a ward sister. She survived cancer in her 30s living to be 90. She had a long, testing decline and demise from dementia, spending six and a half years in a residential home. In that time, she spoke poems I never heard her say before. My dad, having been looked after all his life, became the main carer for my mum; he developed an acute leukaemia and died at the age 78.

My wife is a nurse, my daughter is a nurse. My second daughter is training to be a speech and language therapist, my third daughter wants to be a social worker. My niece is a physiotherapist, currently recovering from coronavirus.

Reflective Exercise

-

What do you think are the types of conditions you will face when caring for frail older people?

-

What types of knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviours do you need to do this compassionately and professionally?

-

‘One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient’ [1, p. 882]. What do you think of this statement?

-

What is it that motivates and inspires you?

This chapter is about rest-of-life care, a concept suggested to me by Elaine Horgan, an NHS manager in 2001. Rather than use ‘end-of-life’, she encouraged me to use the term ‘rest-of-life’. This has since had a beneficial effect on the quality of conversations with relatives, patients and colleagues. The use of positive language, which was not immediately difficult for patients talking about ‘the end’, helped me and my patients and their relatives to talk about what is to come—‘the rest of your life’, a less threatening idea. Having been an NHS General Practitioner (GP) for 25 years, working in Care Homes for 15 years, General Practice and the local hospice, this chapter flows from the past 5 years in a hospital Frailty team. Our multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach uses the principles of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA). CGA is ‘a multidimensional, interdisciplinary diagnostic process to determine the medical, psychological and functional capabilities of a frail older person in order to develop a coordinated and integrated plan for treatment and long-term follow-up’ [2]. Patricia Cantley’s [3] paper boat on the pond illustrates well the concept of Frailty. An origami paper boat floating on a calm pond on a summer’s day only betrays its Frailty when the sun retreats, the wind blows, and the boat is inundated with waves and eventually sinks. With good weather and gentle winds, the future for the paper boat can be good depending on prevailing conditions encountered. Such is the frail patient who is managed well with good care addressing challenges to their health. However, if the storms such as infection or falls strike, the patient’s condition can become unsustainable.

Frailty is not new but, like Dementia, has become an important concept because of the non-specific nature of elderly presentations. The increasing number of older people requiring care is sometimes referred to as ‘the Silver Tsunami’ [4].

The demography of the challenge faced by health and care services will now be considered.

7.2.2 Demography: National and International

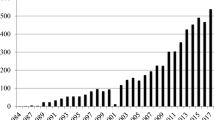

The population statistics below (Table 7.1) indicate that many people in specific parts of the world are living longer.

All health systems are serving ageing populations. The United Nations [6] states:

Globally, the population aged 65 and over is growing faster than all other age groups. In 2018, for the first time in history, persons aged 65 or above outnumbered children under five years of age globally.

In the UK [5], the 85+ age group is the fastest growing and is set to double to 3.2 million by mid-2041 and treble by 2066. Substantial progress has been made to enable people to live to a great age. However, health and social care systems need to be equipped to care for more people living for longer periods with progressive disability, dementia and Frailty. We will now consider the key elements of a Frailty Approach.

7.3 The Key Elements of a Frailty Approach: Defining the Core Concepts

This section will define and explain the core concepts including Frailty, Dementia, Delirium, Co-morbidity, Polypharmacy and Falls. They are foundational to an understanding of effective care of the elderly and relevant to all professionals involved.

7.3.1 Frailty: Definition of a Diagnosis

Frailty becomes more prevalent the older we become and is higher in the over 85s (Table 7.2).

Clegg et al. [8, p. 752] described Frailty as ‘the most problematic expression of population ageing’. Rockwood et al. [9] described Frailty as a clinically valid and valuable concept, however, a difficult term to define well. Moody [10] defined Frailty as ‘reduced resilience and increased vulnerability to decompensation after a stressor event’. The British Geriatric Society [11, p. 6] defines Frailty as:

a distinctive health state related to the ageing process in which multiple body systems gradually lose their in-built reserves.

Rockwood et al. [9] have described a practical, usable and reproducible ‘deficit accumulation model’ of Frailty, which says that ‘small age-related problems add up to give rise to Frailty’ [12]. The clinical frailty scale was developed (Fig. 7.1). It is popular in clinical practice today and has gained widespread recognition because it relies on professional judgement. It is used in many settings to screen for Frailty. It is relevant for health professionals because it provides shareable information. Rockwood [13] wrote: ‘[it gives] information from a clinical encounter with an older person, [to] roughly quantify an individual’s overall health status’. It is this description which is useful and shareable for all health and social care professionals.

7.3.2 Dementia and Its Close Connection with Frailty

A 2020 UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [14] dementia impact report shows that approximately 460,000 people in England are diagnosed with dementia, and a further 200,000 are estimated to be undiagnosed.

Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe a range of progressive neurological disorders, conditions affecting the brain. There are over 200 subtypes of dementia, but the five most common are: Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, frontotemporal dementia and mixed dementia. Mixed dementia is a combination of different types. [15, p. 2].

Dementia contributes to Frailty by damaging brain cells and preventing the brain from functioning normally.

It is estimated that 25% of hospital beds are occupied by someone with dementia. However, the Alzheimer’s Society estimates that this is a very low estimate and states that the figure is far more likely to be as high as 50% [16].

7.3.3 Delirium

This next section introduces you to an important condition that is often overlooked or under-diagnosed when caring for older people

Delirium (or “acute confusional state”) is a common clinical syndrome characterised by disturbed consciousness, cognitive function or perception, which has an acute onset and fluctuating course. It usually develops over 1–2 days [17].

Delirium can be defined as any acute change in normal cognitive state. It can be either hyperactive (restless, agitated with poor concentration) or hypoactive (withdrawn, quiet and sleepy) [18]. Delirium is important because it is a serious condition associated with poor outcomes. However, it can be prevented and treated if dealt with urgently [17].

The causes of both hypo and hyperactive delirium are the same [18]. See Fig. 7.2 below [19].

A good place to start with delirium is to ask a relative or carer the ‘single question to identify delirium’, the SQuID [20]. ‘Is the patient more confused than normal?’ Then the Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT4), a four-question test, is used. It consists of asking place, age, date of birth and current year. It is simple, quick and easy to administer:

The way to propose it to the patient to minimise anxiety is not to start straight in with the questions otherwise they may feel you are trying to catch them out or lay bare their deficiencies. Rather, begin with the question ‘How do you feel about your memory?’, then ask: ‘Would you mind if I ask you 4 quick questions’. Having been asked in such a careful and respectful manner, the patient almost never objects. It is invaluable to be able quickly establish the presence or absence of cognitive impairment in your first moments of assessment.

The AMT4 is a validated rapid initial cognitive estimate. ‘Using a four-question test to determine a patient’s cognitive functioning is very useful since time pressure is at the heart of making a comprehensive enough assessment’ [21]. Importantly, many patients have delirium against a background of dementia. Some have delirium only without any associated or diagnosed dementia. The important thing to remember is that with delirium it is of recent and rapid onset.

7.3.4 Perplexing Behaviour

Delirium and dementia are often characterised by behavioural and psychological symptoms. This is often referred to as challenging behaviour or behaviours that challenge to try to reduce stigma. A better term is perplexing behaviour—which is non-stigmatising, and it states the reality—it is perplexing for patient, carers and health professionals.

7.3.5 Capacity

The main principle here is to ensure that the system acts in the best interests of the patient, which relates to the Mental Capacity Act of 2005. Assessing capacity causes difficulties for health and care professionals.

Assessing capacity needs a consideration of four things:

-

1.

Understanding

-

2.

Retention

-

3.

Evaluation

-

4.

Communication

Capacity assessment involves decision-making such as resuscitation status and preferred place of care when the patient is not able to decide. A patient may be able to decide what they would like for lunch but not have capacity to consent to treatment. Consultation with relatives is important. Remember capacity is decision-specific. Capacity is associated with Powers of Attorney and Deprivation of Liberty. These are referred to in the further learning section.

7.3.6 Polypharmacy: How Medications Can Cause Rather Than Solve Problems

Polypharmacy literally means multiple medicines. The National Service Framework of 2001 established the need for ‘discontinuing inappropriate or excessive medication’ [22]. Polypharmacy can be either appropriate or inappropriate. Polypharmacy increases the risk and predisposition of falls. Older people are more susceptible to side effects, which can lead to falls. A useful mnemonic is CAPTAIN—Check All Prescribing To Ascertain If Needed. Rationalising medication with appropriate deprescribing should be the norm. If you see a lengthy list of medications, approach a colleague who can review this. This will usually be a doctor or pharmacist. More nurses and allied health professionals are becoming prescribers. Regular medication review is crucial in older people, especially in falls and treating delirium. There are guidelines which encourage health and care professionals to think carefully about medications and their unwanted effects. For example, the STOPP/START criteria [23].

Frailty, delirium, dementia, medication side effects and falls are the main problems encountered in caring for older people. Depression is also a problem in old age; however, side effects of antidepressants particularly increased falls risk must be considered. Antidepressants increase falls risk through exacerbating postural drops in BP and slowing response time [24]. The measurement of lying and standing blood pressure to detect postural drops is mandatory in all fallers [25].

7.3.7 Co-morbidities

Co-morbidity or multi-morbidity (the presence of multiple co-morbidities) refers to having two or more long-term physical or mental health conditions [26]. Many of our older people have multiple co-morbidities resulting in cumulative deficits. These deficits can be physical, social, functional and cognitive. For example, one older person could have the following co-morbidities: dementia, diabetes, Frailty and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Multimorbidity results in cumulative deficits.

7.3.8 Falls

Falls happen when Frailty, delirium, dementia, polypharmacy and co-morbidities conspire together.

Falls remain a major cause of injury and death amongst the over 70s and account for more than 50 per cent of hospital admissions for accidental injury [27].

Medications can contribute to the risk of falling such as those used to control blood pressure, diabetes, angina, heart disease, depression, anxiety, enlarged prostate, strong pain killers and sleeping tablets [24].

Everyone who falls should have a lying and standing blood pressure, this is something which is often omitted and, therefore, postural drops missed.

7.3.9 Deconditioning

Muscle loss associated with prolonged stays in bed prejudices recovery. Anti-deconditioning campaigns have become prominent in the UK in an attempt to combat this. The importance of early mobilisation, where possible, encouraged by dressing patients in their own clothes is clear. Initiatives such as ‘End PJ Paralysis’ [28] have been introduced. Patients look so much healthier when dressed in their own clothes, and this approach is to be encouraged. It fits well with CGA.

7.4 Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: Crossing Boundaries Not Patrolling Them

We have looked at the key concepts around care of the older person. These concepts now come together as they combine into the tool called CGA, which will equip you with the skills you need to undertake assessment and treatment of the older person with confidence, whether your core expertise is social care, nursing, therapy or medicine.

Crossing Professional and Practical Boundaries Not Patrolling Them: A Frailty team is part of everyone’s team looking to interact with all professionals involved in a person’s care. An ‘approach’ is the way we assess and build a picture of the patient. Engaging with patients is always time-pressured in whatever setting you find yourself, hence the emphasis is on a ‘comprehensive enough’ assessment.

7.4.1 Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: A Proven Tool

Frail older patients often present in a non-specific way with one or more of the 5 Is: instability (falls), immobility, iatrogenic presentations (polypharmacy), impairment of cognition and incontinence [29].

CGA is a tool which is aimed at breaking down the complexity of the presentations of older people into manageable chunks. It is accessible to all health and care professionals and depends on contributions from all professionals involved. All of their core skills create an accurate and shareable picture of the patient’s presentation. Too often, different caring professions complete their tasks in isolation. This is a way of integrating health and social care assessment in a constructive and beneficial way. It benefits the professionals involved by encouraging dialogue. The fact these professionals work in the same team means they are easily accessible to each other. A practical and helpful definition describes CGA as:

A process of good, holistic care delivered within a geriatric-medicine-focused multi-disciplinary team, which goes above and beyond simply managing the acute problem that the person has presented with’ [30].

The evidence for the success of CGA is threefold:

-

1.

It leads to better outcomes than ‘usual medical care’ (going beyond addressing just the problem the patient presented with, for example, pneumonia)

-

2.

CGA makes people more likely to be alive in a year and to be living a less-dependent life.

-

3.

It has been so successful that it is being used in other disciplines [30].

Recent developments have seen it used to assess patients following fractures (ortho-geriatrics) and in cancer patients (oncogeriatrics). It is also being used to assess patients, where surgery is being considered (POPS: Preoperative pre-surgical assessment). CGA needs the skills of all the multidisciplinary team, that is, all the caring professions, otherwise it loses its benefits [30].

7.4.2 The Four Domains of the CGA: MSFC—Medical, Social, Functional and Cognitive

Assessment takes time but can be done initially rapidly and can be repeated going deeper each time.

-

Quick example of the usefulness of CGA—86 years patient comes in—witnessed fall, from a Care home, reduced mobility. Medical—Fall, Social—Residential Home, Function—wheeled Zimmer Frame, Cognition—Known dementia. Immediately the goal of care will be to return this patient to their Residential home once their appropriate investigations have been completed, including medication review (CAPTAIN), bloods and x-rays, discussion with carers, mobility assessment and assessment of cognition. Lying and standing blood pressure checked once fractures excluded—LSBPCOFE!

7.4.2.1 Medical: A Foundation But Only 25% of the Story

The medical domain of a CGA must include the presenting problem, past medical history and the current medication of the patient as well as allergies. It is an important part of the assessment but is only 25% of it. The social, functional and cognitive aspects remain essential to the patient’s progress. In drawing together the medical element of a CGA, use can be made of the following sources: general practitioner (GP) computer systems, social care records, phoning local social services, paramedic admission sheets, GP admission letters and emergency department (ED) letters.

7.4.2.2 Social: The Context of Day-to-Day Living

The social domain must include significant others, care packages and agency contact numbers. This part is about recruiting allies for the ongoing care of the patient outside of hospital. Communication and consultation with relatives and carers has helped me greatly in my practice in terms of accurate history and planning future care.

It is important to engage the skills and knowledge of local social care professionals as early as possible as they know how to navigate the often-confusing array of care providers and funding issues.

7.4.2.3 Functional: The Importance of the Multidisciplinary Approach

This domain includes home layout including stairs, toilet and washing provision, whether upstairs or downstairs, activities of daily living (ADLs) and mobility assessment, use of walking aids such as Zimmer frames and continence.

One of the key tenets of CGA is the skills of therapists, particularly physiotherapists and occupational therapists. The importance of optimising mobility and dealing with environmental considerations is crucial.

7.4.2.4 Cognition: Rapid But Accurate

Impaired cognition brought by impaired vision and hearing is identified—poor sight and hearing should be recorded, and hearing aids and glasses found. Cognition can be assessed with the AMT4 and SQuID (single question to identify delirium): ‘Is this person more confused than before?’ The AMT4 can be supplemented later in the patient journey by the 4AT delirium screen.

7.4.2.5 Summarising: Recording and Making a Plan of Care

A CGA can be simply summarised under the four headings: medical, social, functional and cognitive problems leading to a plan of goals. Admission or discharge of the patient into the appropriate clinical setting is guided by the CGA. CGA is not a once-and-for-ever event. It is used as the repeated way of processing the current presentation of the patient to inform ongoing and future care.

7.5 Practical Application of CGA: A Clinical Scenario Employing Tips and Tools Described in This Chapter

Case:

Violet is 92 and lives alone. She is admitted to the ED after being found on the floor at home by the 9 a.m. carer. No active bleeding, she has been conveyed by the ambulance service because of left hip pain. Violet has dementia—confusion suddenly worse in last 2 days according to carer. She is on 12 different medications.

Reflective Exercise:

Initial Consideration of the Following

-

Which of the 5 Is is Violet presenting with?

-

1.

Immobility: Yes, currently, what is her normal baseline mobility?

-

2.

Instability: Yes

-

3.

Iatrogenic: Yes, probable polypharmacy—12 medications

-

4.

Incontinence: Perhaps—check with the carers.

-

5.

Impairment of cognition: Do the SQuID and AMT4—place, age, DOB, year (PADY)

-

1.

-

What are her medical problems (include consideration of the possible harmful effects of medications)?

-

What are her social problems?

-

What are her functional problems?

-

What are her cognitive problems?

-

Document sources of your information with contact numbers—it will help you later. Next consider the problems Violet presents under the following headings:

-

Medical Problems: Initial assessment to exclude sepsis. Fall, polypharmacy, Frailty (Rockwood level—6)—consult computerised and paper records. Lying and standing blood pressure required, given the fall and polypharmacy (Defer until hip fracture has been excluded but ensure requirement recorded in notes as a reminder to self and colleagues). Ensure appropriate assessment by medical colleague with documented BP, pulse regular/irregular, temperature, oxygen saturation and appropriate blood samples. Imaging of left hip. Violet also needs a computer tomography (CT) of her brain because she is taking an oral anticoagulant for atrial fibrillation and, therefore, may have had an intra-cerebral bleed [31]. Her worsened confusion could be compounded by a head injury.

-

Social Problems : Does she live in a house/flat or care home? Has she got family? Enlist their support. Ring them if not present. Are they coping? Does she have a package of care?

Package of care in place for the last 3 years (information from social services as care agency unavailable. Also give your daughter’s contact number).

Next of kin is a daughter who lives 200 miles away, she comes infrequently and does weekly food shopping online. House with stairs. Widow for 10 years.

-

Functional : Consider ADLs, mobility, use of aids and continence. Consider the environment—stairs? Where does she sleep? Where is the loo –upstairs or downstairs?

Violet lives downstairs with a commode for toileting as she can no longer manage the stairs and no downstairs loo. She uses a Zimmer frame and is unsteady on her feet (information from daughter by phone). She is incontinent of urine with occasional faecal incontinence. Pads from bowel and bladder service.

-

Cognitive : Use a quickly administrable and recordable AMT4: place, age, DOB, year and record the score. Presence or absence of cognitive deficit is an important initial feature to capture by also using the SQuID.

The SQuID: ‘Is the patient’s confusion worse than normal?’ Care Agency Golden Days 9 a.m. carer confirmed to daughter that Violet has been more agitated and anxious in last 2 days. Violet scores 1 out of 4 on the AMT4—place x, age x, DOB correct, year x.

-

-

How would you summarise your information, record it and establish the overall goal of this episode? To whom would you refer the patient?

This information is recorded under the four headings:

-

Medical: moderately frail lady of 92 years, background of hypertension, vascular dementia, previous stroke, carcinoma of breast 15 years ago. Fall possible head injury. Increased confusion/agitation for 2 days.

Rockwood Clinical frailty scale—6.

-

Social: Package of Care Golden Days agency 01625 444 323, 3 × daily.

Daughter Fiona, London. 020 7345 2001. Online shopping. Visits fortnightly.

Neighbours ‘look in.’ Suggests patient vulnerable overnight.

-

Function: House with stairs. Downstairs living, Zimmer frame, unsteady, fall 3 months ago

Baseline: able to stand independently and transfer

Incontinent of urine, occasional faecal incontinence, pads from bladder/bowel service

-

Cognition: AMT4 1/4 Hearing aids—left at home, poor sight. Known dementia

Plan

-

Get hearing aids and glasses from home

-

Refer to orthopaedics (bone fracture specialists)—confirmed L fracture neck of femur on X-ray

-

Computerised tomography Brain scan—no bleeding identified

-

Lying/standing blood pressure later because of fracture. Medicines optimisation (note Violet is on 12 medications)

-

Needs deprivation of liberty safeguard as lacks capacity to consent to treatment currently

-

May require intermediate (step down) care and then possible nursing home placement. Dr Jones has mentioned discussion of resuscitation status with daughter Fiona because of advancing Frailty and co-morbidities. For further discussion if condition worsens. Violet unable to engage with discussion. Daughter has Power of Attorney for Health and Wealth.

-

From discussion with Violet’s daughter, preferred place of care is home

-

Handover to orthopaedic ward completed

Having looked at a clinical scenario, which demonstrates CGA in action, further areas for consideration going deeper are suggested next.

7.6 Summary

This chapter demonstrates the complex and often non-specific nature of older people’s presentations clearly describing a tool to break that complexity down into manageable ‘bite-size’ pieces. That tool is CGA. The value of CGA is shown. It integrates the input of all the care professionals involved. Frail elderly people require care beyond purely medical considerations. CGA also describes patients’ social, functional and cognitive problems—a Frailty Approach.

The key elements of a Frailty approach are described. The value of being able to quantify an older person’s overall health status and be able to share that information with colleagues [13] is explained. The essential nature of an MDT approach is also explained. How that approach considers the key concepts of dementia, delirium and polypharmacy is described.

The CAPTAIN maxim is introduced—‘Check All Prescribing To Ascertain If Needed’. The burden of falls and their incidence and causes, often related to polypharmacy, is described, along with the importance of ensuring every faller has a lying and standing blood pressure recorded and evaluated.

Having described the Frailty team and its ability to challenge traditional care boundaries and roles, its main tool CGA is outlined with its proven benefits of improving survival and keeping people in their own homes. The four domains of CGA are then described in detail. How medical, social, functional and cognitive problems contribute to overall health status is demonstrated, with clear care planning made possible. The scenario of 92-year-old Violet’s presentation to hospital shows how the principles described are applied in practice.

Further learning opportunities are described below with information about the people and organisations making a difference to the care of older people.

I would like to acknowledge the dedication and support of my colleagues in the Frailty team at Macclesfield hospital as well as Sian Harrison, Cheshire Advanced Dementia Team for help with Demography, Dr. Dawn Moody for the term ‘Frailty Approach’ and Elaine Horgan, NHS Manager for the term ‘rest-of-life’.

7.7 Taking It Further: Suggested Further Reading

MDTea Podcasts. ‘The MDTea is a project with an interest in podcasts and the power of storytelling. A suite of resources for those health and social care professionals that are lucky enough to work with older people’. http://thehearingaidpodcasts.org.uk/about/

The British Geriatric Society—all things relevant to older people’s care. bgs.org.uk

Dawn Moody, Former Deputy National Director for Older People at NHS England, has created resources to benefit patient management, for example, the Virtual Reality Frailty experience along with the Frailty toolkit: https://www.frailtytoolkit.org/frailty360-intro/

Ethics of care—the 4 principles of Respect for Autonomy, Beneficence, Non-maleficence and Justice. Useful guide to ethical care when facing the dilemmas posed by elderly patients. Tom Beauchamp and James Childress, Principles of biomedical ethics, 8th Edition, Oxford University Press, New York, January 2019.

End of Life issues. The Cheshire Advanced Dementia Support Team aims to guide and educate professionals and informal caregivers. http://eolp.co.uk/advanced-dementia-support-team/. The Gold Standards Framework led by Professor Keri Thomas. https://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk

Dementia Friends run by the Alzheimer’s Society—Accessible to all community groups for free. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-involved/dementia-friendly- communities/dementia-friends

Admiral nurses—Dementia UK—the work of specialist dementia nurses. https://www.dementiauk.org/?gclid=CjwKCAjw2a32BRBXEiwAUcugiE-1nho4euQJDyeEnTQo9gb6OSlfJJv08MK8AvPfriHlXhsHp_RfehoC0Q0QAvD_BwE

Power of Attorney—Age UK, (2019), Making sure your wishes are respected https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/information-guides/ageukig21_powers_of_attorney_inf.pdf

DoLS—Lorraine Curry, (2017), Quick Guide to Deprivation of liberty Safeguards https://www.adass.org.uk/media/5896/quick-guide-to-deprivation-of-liberty-safeguards.pdf (DoLS).

References

Peabody FW (1927) The care of the patient. JAMA 88:876–882. https://depts.washington.edu/medhmc/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/Peabody.html. Accessed 28 June 2020

Roberts H, Conroy S (2018) Hospital wide CGA. https://www.bgs.org.uk/resources/hospital-wide-comprehensive-geriatric-assessment-how-cga-history-of-the-project. Accessed 27 Mar 2020

Patricia Cantley (2018) The Paper Boat. British Geriatric Society. https://www.bgs.org.uk/blog/the-paper-boat. Accessed 25 May 2020

Weinstein S (2015, April 2) The ‘Silver Tsunami’, Choosing how and where we age. [Web log post] https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/what-do-i-do-now/201504/the-silver-tsunami. Accessed 1 Mar 2020

Age UK (2019) Later Life in the United Kingdom 2019. https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/later_life_uk_factsheet.pdf. Accessed 20 Mar 2020

United Nations (2019) Ageing, trends in population ageing. World population prospects: the 2019 revision. https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/ageing/. Accessed 20 Mar 2020

British Geriatric Society (2014) Fit for frailty. https://www.bgs.org.uk/resources/resource-series/fit-for-frailty. Accessed 24 June 2019

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K (2013) Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 381(9868):752–762

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A (2005) A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 173(5):489–495. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050051

Moody D (2016) Identifying and understanding frailty. The North East Frailty Summit 5th Dec 2016. http://old.ahsn-nenc.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2016/11/Dawn-Moody.pdf. Accessed 6 Jan 2020

British Geriatric Society (2014) Gill Turner, Fit for Frailty Part 1, Consensus best practice guidance for the care of older people living in the community and outpatient settings. A report by the British Geriatrics Society in association with the Royal College of General Practitioners and Age UK, p 6. https://www.bgs.org.uk/sites/default/files/content/resources/files/2018-05-23/fff_full.pdf. Accessed 24 June 2019

Rockwood et al (2020) Geriatric medicine research, our work on frailty and deficit accumulation. Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. https://www.dal.ca/sites/gmr/our-work.html. Accessed 27 Mar 2020

Rockwood et al (2020) Geriatric medicine research, our tools. https://www.dal.ca/sites/gmr/our-tools/clinical-frailty-scale.html (Permission for use granted https://www.dal.ca/sites/gmr/our-tools/permission-for-use.html). Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Accessed 23 Mar 2020

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2020) Impact Dementia. https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/into-practice/measuring-the-use-of-nice-guidance/impact-of-our-guidance/niceimpact-dementia. Accessed 30 Mar 2020

Dementia UK (2020) Understanding dementia, what is dementia? https://www.dementiauk.org/get-support/diagnosis-and-next-steps/what-is-dementia/. Accessed 30 Mar 2020

Alzheimer’s Society (2016) Fix dementia care: hospitals, p 10

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2010) Delirium: prevention, diagnosis and management Clinical guideline [CG103]. Last updated: 14 Mar 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg103/chapter/Introduction. Accessed 22 May 2020

Preston J, Wilkinson I (2016) The hearing aid podcasts - episode 1.2 delirium. http://thehearingaidpodcasts.org.uk/episode-1-2-delirium/. Accessed 22 May 2020

Thomas D, Wykes L (2018) Delirium infographic PINCHME. Delirium: top tips. https://www.lindadykes.org/infographics. Accessed 1 June 2020

Han JH, Schnelle JF, Wesley Ely E, Wilson A, Dittus RS (2018) An evaluation of single question delirium screening tools in older emergency department patients. Am J Emerg Med 36(7):1249–1252. in White KL (2019) Screening methods to identify delirium in the Emergency department. Masters in Geriatric Medicine, University of Salford, p 32

White KL (2019) Screening methods to identify delirium in the Emergency department. Masters in Geriatric Medicine, University of Salford, p 44

Department of Health. National Service Framework for older people, standard 6: Falls, p 80. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/198033/National_Service_Framework_for_Older_People.pdf. Accessed 24 June 2019

O’Mahony D et al (2015) STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. https://academic.oup.com/ageing/article/44/2/213/2812233. Accessed 24 June 2019

Darowski A (2008) Falls the facts. OUP, Oxford, p 67

Royal College of Physicians (2017) Measurement of lying and standing blood pressure: a brief guide for clinical staff. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/measurement-lying-and-standing-blood-pressure-brief-guide-clinical-staff. Accessed 16 Jan 2020

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2016) Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management. NICE guideline [NG56]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG56/chapter/Recommendations#multimorbidity. Accessed 24 June 2019

Age UK (2010) Falls in the over 65s cost NHS £4.6 million a day. https://www.ageuk.org.uk/latestpress/archive/falls-over-65s-cost-nhs/. Accessed 24 June 2019

NHS England (2018) EndPJParalysis: the revolutionary movement helping frail older people. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2018/06/endpjparalysis-revolutionary-movement-helping-frail-older-people/. Accessed 28 June 2020

Morley JE (2017) The new geriatric giants. https://www.geriatric.theclinics.com/article/S0749-0690(17)30037-X/fulltext. Accessed 21 Jan 2020

Preston J, Wilkinson I (2016) The hearing aid podcasts - Episode 1.1 comprehensive geriatric assessment. http://thehearingaidpodcasts.org.uk/episode-1-1-comprehensive-geriatric-assessment/#. Accessed 22 Mar 2020

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2019) Triage, assessment, investigation and early management of head injury in infants, children and adults. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg176/chapter/1-recommendations

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

McKay, J.A. (2021). The Frailty Approach: Rest-of-Life Care of the Older Person. In: McSherry, W., Rykkje, L., Thornton, S. (eds) Understanding Ageing for Nurses and Therapists. Perspectives in Nursing Management and Care for Older Adults. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40075-0_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40075-0_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-40074-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-40075-0

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)