Abstract

In recent decades, social assistance programs spread across countries in the Global South. In this chapter, it is argued that whether a country has a social assistance program or not also depends on its colonial legacy. Colonial empires differed in their notions on the role of the state regarding social protection which still have consequences for today’s social policy-making. Using a sample of more than 100 low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) and applying panel estimation techniques, I analyze the influence of the French and British colonial legacy on the spread of two of the most important social assistance programs. The empirical findings show that the French and British colonial powers influenced the social policy configurations of their former colonies in each specific way. For example, the French imperial power enforced a strong social insurance principle during colonial times which still today decreases the likelihood of introducing social assistance programs in former French colonies.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

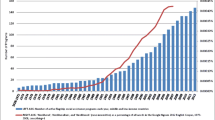

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century there has been a rapid rise in social protection initiatives in many low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) that can be mainly attributed to a growing number of social assistance programs. Nowadays, around 70% of all developing countries have at least one social assistance program in place (Dodlova et al. 2016, 8). Social assistance programs are public and noncontributory schemes funded from general tax revenues to guarantee access to essential health care and basic income security to individuals and families in need (Leisering and Barrientos 2013; Midgley 1984a). The recent spread and expansion of social assistance reflects a shift away from contributory-based social insurances implemented in the early days of social protection in the Global South, providing benefits for workers in the formal labor market. Social insurance, which still is the predominant form of social protection, typically covers only a very small, privileged group of society. The majority of the people are often excluded because of working in the informal labor market or of not being able to pay contributions. Social assistance as noncontributory social protection is assumed to be better able than social insurances to expand coverage to the more vulnerable groups of the society and to face poverty and inequality (Dodlova and Giolbas 2015, 4; Overbye 2005; Eckert 2004, 472; Barrientos 2011). Figure 6.1 shows the spread of two main social assistance programs across LMIC, namely social pensions (left) and unconditional family support programs (right) over the last decades.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) and the World Bank have also acknowledged the need for social assistance schemes and started to promote these programs. However, the active promotion of social assistanceFootnote 1 requires a profound understanding of what is driving its introduction and why some countries follow the recent trend and adopt social assistance programs and others do not. Studies analyzing the spread of social assistance emphasize the importance of democratic institutions. Unlike autocratic settings, democratic institutions exert pressure on politicians to implement policies from which the majority of the population benefits. Since social insurance systems typically include only a small segment of society, democratic leaders have an incentive to expand social protection via noncontributory social assistance programs. However, I argue that this narrative only holds in the case of certain institutional preconditions. Whether a country has a social assistance program or not also depends on its colonial legacy. The colonial legacy has defined and still shapes the opportunities of governments for social policy reforms. Colonial empires differed in their imperial strategies and in their notions on the role of the state regarding social protection. These differences influenced early social protection legislation and still have consequences for today’s social policy-making.

Surprisingly, the colonial heritage of social protection has been almost completely left out of the equation in comparative social policy research (Kpessa and Béland 2013; Overbye 2005; Schmitt et al. 2015). This is astonishing considering the fact that most developing countries have a colonial history and a great majority of early social protection programs in former colonies were introduced before those countries gained independence (Schmitt 2015). Literature that discussed the effect of the colonial legacy mainly focused on political (Lange 2004) and economic development (Acemoglu et al. 2001; Grier 1999; Englebert 2000). However, the omission of the colonial legacy in the analysis of determinants and consequences of early and post-independent social protection precludes a systematic grasp of contemporary social problems.

To analyze the influence of the colonial legacy on the contemporary spread of social assistance, this chapter uses a sample of ca. 100 LMIC and estimates cross-section and binary time-series cross-section logit models. I focus on two of the most important social assistance programs, that is, social pensions and unconditional family support schemes.Footnote 2 Moreover, I limit the discussion of the colonial influence to the British and French colonial powers. Both were the two main colonizers in the twentieth century—when social protection was put on the global agendaFootnote 3 and became actively introduced into the debate on social affairs after World War II.

The empirical findings show that the French and British colonial powers influenced the social policy configurations of their former colonies in each specific way. The French imperial power enforced a strong social insurance principle during colonial times which still today decreases the likelihood of introducing social assistance programs in former French colonies. The effect of the French colonial legacy even outweighs the positive influence of democratic political institutions. On the other hand, former British colonies very early introduced social assistance programs, due to the poor law tradition and the compatibility to the British Beveridgean notion of the welfare state, which highly inspired the whole British Empire. The findings show that the colonial heritage of a country has to be taken into account when explaining different pathways of social protection in most LMIC. That does not imply that national factors are unimportant for social policy-making but rather that the colonial legacy influences the effects of domestic conditions. The colonial heritage is one factor shaping the possibilities of policy-making and the institutional choices a government has nowadays.

The chapter is structured as follows. The next section elucidates the arguments why the colonial legacy should still have an influence on the recent spread of social assistance. The subsequent section presents details on the data and method applied. The then following section analyzes the influence of the colonial legacy on the expansion of social pensions and unconditional family support programs across the sample of LMIC. A final section presents a conclusion.

The Colonial Legacy of Social Assistance

Many studies focusing on the emergence and rise of noncontributory social assistance emphasize the role of democratic institutions (Brooks 2007, 2015; Dodlova et al. 2016). Democratic leaders aiming at extending social protection to groups that have been excluded from contributory social insurance are assumed to opt for social assistance. Noncontributory social protection is often the only available option toward more inclusive social protection because of being independent from formal wage employment, previous contributions and individual financial capabilities (Leisering and Barrientos 2013). Besides studies elucidating the favorable consequences of democracy, the diffusion literature emphasizes the importance of spill-over effects between neighboring countries. Countries are more likely to introduce social assistance if neighboring countries have done so before. However, spill-over effects and the influence of democracy are only part of the story. I argue that the colonial legacy has to be taken into account to obtain a more comprehensive picture of the expansion of social assistance and to explain why some LMIC have introduced social assistance and others have not. In the following, I first briefly address why colonial powers became engaged into social policy-making at all and afterward elucidate why and how the French and British colonial Empires with their general colonial policies and welfare state principles do influence contemporary trends in social protection in LMIC.

Colonialism and Social Policy

In the late nineteenth and in the first half of the twentieth century, the question of how to deal with social risks in the case of income loss was mainly restricted to the Western world. During much of this period, colonial powers typically aimed at exploiting labor in their colonies and did not pay much attention to how workers in the colonies were protected in the case of work accidents and illness. Hence, colonial powers were not involved in the provision of social services in their colonies until the first decades of the twentieth century (Midgley and Piachaud 2011). From the 1930s and 1940s onward, the labor question in dependent territories became increasingly relevant (Eckert 2004). Labor movements gained importance in many of the colonies, and a number of colonies experienced massive strikes, particularly during World War II and the immediate post-war period (Orr 1966). Moreover, social protection in the dependent territories increasingly became a topic of debate for international organizations, particularly the ILO. In 1944, the ILO member states agreed that the basic standards of labor policy defined by the ILO should also be applied to non-metropolitan areas (Maul 2012; Plant 1994; Kott and Droux 2013). In addition, the human rights declarations of the victorious allies of World War II were an implicit challenge to the imperial systems of European states. The colonial powers could no longer ignore increasing demands for social protection and aimed at a moral upgrade after World War II (Eckert 2004, 479–480). In sum, by midway through the twentieth century, not only was there pressure on the colonial powers from inside the colonies, in the form of rising demands for social protection, but also from the outside, for example in the form of soft pressure by international organizations. As a consequence, colonial powers became more and more engaged in social policies in their colonies.

Two colonial powers highly involved in the debate around social affairs after World War II were France and Britain. However, both differed widely with respect to their notions and concepts of the state, the labor question and social protection (Mahoney 2010). I argue that these differences still have consequences for today’s social policy-making and help to explain why some countries have introduced social assistance schemes and others not, independently, for example, of the economic prosperity and quality of democratic institutions.

British Colonization Strategy and Poor Law Tradition

In the 1940s, questions around social protection and the welfare of workers in dependent territories were also discussed in Great Britain. The debate in the British Empire was characterized by two main peculiarities which not only shaped the post-war debate on social protection in former British colonies but also are still relevant for contemporary social policy-making.

First, Great Britain practiced a decentralized colonization strategy and was committed to a passive view on the role of the state with regard to social protection in their colonies. It often incorporated the local elite and maintained traditional structures of social service provision, for example, for the elderly and other needy groups (Williamson and Pampel 1991, 23). As a consequence, early social protection legislation in former British colonies was more heterogeneous than in many other empires, since colonies had a comparably large maneuvering room. For example, in the case of retirement schemes, countries and territories such as India, Nigeria and Tanzania introduced provident funds, Botswana, the Seychelles and Jamaica flat rate pensions, and Zambia and Yemen wage-related schemes (Schmitt 2015). Against the background of this decentralized colonial administrative structure, British officials did not force encompassing changes. Legislation was implemented by local political leaders in their colonies. The British officials were rather reluctant to actively push the implementation of specific social policies, and the colonial office often only emphasized the urgency of specific legislations (Eckert 2004).

Second, the debate on social protection in the dependent territories was influenced by the poor law tradition in Britain. The British Poor Law tradition dates back to the Elizabethan Poor Law Act of 1601 (Overbye 2005). It was the first nation-wide poor relief regulation in modern times, which aimed at bringing the able-bodied poor to work. In 1834, a new poor law was enacted which tightened the old poor law that had become too expensive in the course of industrialization. The British poor laws resemble very much the current trend of social assistance in the Global South. Both are noncontributory in nature, and in both cases social policy is considered an instrument of poor relief rather than of income maintenance. Already in the early twentieth century the British poor laws served as a role model and inspired some progressive colonies which adopted these ideas and introduced poor relief programs and social assistance schemes in line with the British model (see Künzler, Chap. 4, this volume). For example, Mauritius adopted a poor relief ordinance in 1902, South Africa introduced a noncontributory and means-tested old age pension in 1928 (Seekings 2013, 311), and a poor relief ordinance was passed by Trinidad and Tobago in 1931 (Seekings 2013, 312; Midgley 1984b, 22). These social assistance schemes often remained in place after decolonization or were even extended by the new governments and administrations, for example to colored people (Midgley 1984b, 27).

These two British specifics also shaped the debate on social protection in overseas territories in the 1940s. This debate was intensified by the Beveridge Report from 1942 which led to the formation of commissions on social affairs in several dependent territories across the entire British Empire (Surender 2013; Seekings 2008). After World War II, it was controversially discussed whether tax-financed social assistance schemes could be introduced throughout the British Empire. Some British officials, for example, in the Economic Department, favored noncontributory over contributory schemes (Seekings 2011, 167), while others considered an implementation of comprehensive social assistance too expensive and therefore impossible to implement. Although the discussions in the British Empire did not result in any systematic or uniform handling of social affairs in overseas territories and finally the British officials considered it unrealistic to adopt large scale social assistance schemes in all dependent territories, they brought the introduction of such schemes into the debate at a very early stage. This highly influenced the discourse about the labor question in British overseas territories. As a consequence, the implementation of social assistance programs was discussed much earlier within the entire British Empire than anywhere else. This early presence of ideas about social assistance and the early existence of social assistance schemes in the motherland, but also in some colonies, were to increase the likelihood of following the recent policy trend of introducing social assistance programs in former British colonies.

When looking at the specific risks covered within the British Empire and in Great Britain itself, social assistance traditionally focused on elderly people. For example, in Great Britain the Old Age Pensions Act of 1908, as the beginning of the system of modern state pension, stipulated the entitlement to a tax-funded old age pension for elderly people lacking sufficient income (see Seekings, Chap. 5, this volume). This retirement scheme is very similar to the current trend of social pensions. But also the early social assistance programs in Mauritius, South Africa and Namibia addressed the needs of the elderly. In contrast, family allowances remain “a contested part of a welfare system” (Pedersen 1993, 415). Especially in colonial societies during colonial times, Britain favored male breadwinner wages. Family allowances were regarded as inefficient in African societies by British officials because allowances would not only finance children but often many other dependent relatives as well (Lindsay 1999, 802).

In sum, the poor law tradition with its focus on poor relief rather than on income maintenance for industrial workers and the early discussion of social assistance in the former British Empire were to enhance the probability that former British colonies implemented noncontributory social assistance programs (Seekings 2013). Moreover, the positive influence of the British colonial footprint on the introduction of social assistance was to especially apply to social pensions but less to family support schemes.

French Social Insurance Tradition

In France, as the second major colonial power of the twentieth century, the debate regarding social protection also accelerated in the 1940s. Two main characteristics relevant for contemporary social protection made the debate within the French colonial empire different from that in other empires.

First, France followed a pro-active colonial policy, emphasizing the decisive role of the state in enhancing social and economic prosperity (Cooper 1996; Iliffe 1987). French officials held the view that the colonies could not develop themselves but rather needed the initiative of the French Administrative Authority (MacLean 2002). The French colonial power regarded “the colonies simply as a prolongation of the mother-country beyond the seas” (Fieldhouse 1967, 308). The French imperial mission was characterized by the view that the Republic was one and indivisible. As a consequence, the French imperial system aimed at reproducing the French model in its colonies in all areas (see Becker, Chap. 7, this volume). In contrast to Britain, France centralized its power and, at least theoretically, made all basic and important decisions in Paris, where after 1894 colonial officials were trained in the École Coloniales (Fieldhouse 1967, 310). The consequence was an autocratic system of colonial government (Grier 1999, 319; Fieldhouse 1967, 308). Even though the French appointed Africans in order to fulfill administrative functions, these administrative elite owed their positions to France. The French aimed at producing an elite population in the colonies that was completely committed to the French culture, with a status comparable to that of French citizens. However, only a small portion of the native population achieved this status and became citizens (Fieldhouse 1967, 315). The great majority kept their status as colonial subjects liable to the Code de L’Indigénat which determines the inferiority of colonial people.

Second, one basic characteristic of the French welfare state is the strong social insurance tradition (Kaufmann 2013, 155). It is largely based on the principle of occupational solidarity. This means that social protection is linked to the occupational status of the insured person, his or her earnings and in consequence the contribution record (Béland and Hansen 2000, 512). Earning-related benefits based upon individual contributions are only provided to workers and their family in formal wage employment. Each risk is separately administered and managed within different social insurance schemes and often separated by different occupational groups (Palier 2000, 116). For example, each profession has its own pension scheme, leading to a very fragmented pension system which is highly resistant to change. France itself did not have any comprehensive social assistance system for people in need (Béland and Hansen 2000, 52). The only exception was family allowances. France implemented the Code de la Famille in 1939, as the first “comprehensive legislation on family policy anywhere in the world which pays universal benefits to all French citizens and residents for the second child and subsequent children” (Béland and Hansen 2000, 52). One main reason for this exceptional character of family policy was France’s fear of a power imbalance and a military advantage for the German army due to the depopulation of France itself (Echenberg 1975, 179).

These two features characterized the debate on the introduction of social protection for workers in overseas territories in the 1940s. After a series of strike waves in French West Africa the French officials came to the view that conditions for workers had to be improved. From 1946 onward, after formally abolishing the Code de L’Indigénat , that is, the inferiority of the native population, a committee at the Ministry of Overseas Territories was working on a plan to extend social protection to workers in the colonial states. However, officials had to define who a worker was and which rights were associated with this status. After six years of debate, the French Code du Travail for overseas territories was passed in 1952, as the key milestone of social protection legislation in the French colonies. The Code contained many specific regulations regarding social protection programs, and it strongly reflected France’s social insurance tradition. For example, it stated that family allowances and systems to protect workers from illness and accidents should be introduced in the colonies. However, according to the Code du Travail only those workers were included who were part of the formal labor market or were citizens (Fieldhouse 1967, 312; Eckert 2004, 481). The Code du Travail therefore excluded customary workers, workers on the informal labor market or people “compensated by land or crops” (Cooper 1989, 754). Due to the centralized approach of France, the Code du Travail applied for all colonies at the same time. After gaining independence, the former French colonies “all maintained the basic text and structure of the Code du Travail in 1952” and therefore the strong social insurance tradition of the welfare state (Cooper 1996, 464).

Regarding scheme specific differences, also family allowances played an exceptional role in the colonies (Eckert 2004, 482). As family allowances were much more important in the French welfare system (Lindsay 1999, 810), the Code du Travail also reflects the importance of supporting the nuclear family as part of the social protection of workers.

In sum, France had a very strong social insurance tradition, and the French administration clearly pushed for the establishment of social security systems similar to the French social insurance model. As a consequence, all former French colonies introduced social protection schemes which first of all followed heavily social insurance principles. This strong social insurance setting was to make it much more difficult for former French colonies still today to implement noncontributory social assistance. A complete shift from one system to another, with the abolishment of the old one, is highly unlikely and would come along with high transaction costs. This is illustrated by the fact that almost no country has abolished a social insurance scheme once it has been established (ILO 2017). Therefore I assume that under otherwise equal conditions former French colonies are less likely to have social assistance programs. Furthermore and against the background of the importance of family allowances and its exceptional character in France itself, French colonies are more likely to have introduced noncontributory family support schemes than social pensions.

Summary

The main argument is that different imperial powers with different notions of the welfare state adopted different colonization strategies. For example, the French welfare state is characterized by the principle of social insurance and income maintenance rather than by poverty alleviation as it is the case with the British welfare state. In France, the social question was considered a worker’s question, while in Great Britain it was more a poverty question (Kaufmann 2013, 100). These differences result in different logics of contemporary social policy-making. After having gained their independence, all French colonies maintained the social insurance nature of social protection that has been characteristic for the French notion of the welfare state. The strong social insurance tradition in former French colonies, reflecting the principles of the French welfare state, would require a complete modification of existing institutions, practices and power structures if social assistance schemes were supposed to be introduced. The costs of implementing the recent trend of social assistance are therefore disproportionally high, as the policy trend does not fit to the existing institutional setting. A strong social insurance tradition may therefore be supposed to tremendously decrease the likelihood of having a social assistance. In contrast, in former British colonies the poor law tradition and the early debate on noncontributory social protection make social assistance a concrete, available policy option, as early bird countries such as South Africa have shown. Moreover, British colonies are more likely to have social pensions than family support schemes, since poor laws and early social assistance typically have focused on protecting the elderly. Family policy has not been a central issue of the British welfare state.

The Rise of Social Assistance in the Global South: Data and Methods

The empirical analysis proceeds by two steps. First, I estimate cross-section logit models to explain which countries have a noncontributory social pension or a family support scheme for the most recent period of time, since this allows for integrating a broader set of control variables. In a second step, I estimate binary time-series cross-section (BTSCS) models which additionally allow for an analysis of the time dimension.

The dependent variable is the introduction of two of the most important and most frequent noncontributory social assistance schemes, namely social pensions and unconditional family support schemes. Social pensions are noncontributory cash transfers paid regularly to elderly people (HelpAge International 2017). They are widely acknowledged to be one of the most effective tools to reduce old age poverty and invest in human capital development. Data on social pensions are taken from HelpAge International which provides a large database on social pensions in 107 countries. The information coming from HelpAge International is cross-validated with information provided by the ILO (2017) and Dodlova et al. (2016). Unconditional family support schemes are “transfers targeted to low-income households or specifically to children” (Dodlova et al. 2016, 9). These schemes “range from a basic safety net for those below the poverty line to (universal) child support grants” (Dodlova et al. 2016, 9). Data for unconditional family support schemes are taken from the Noncontributory Social Transfer Database which includes information, on a program-basis, about 186 programs in 101 countries (Dodlova et al. 2016).

In both cases the dependent variable is measured by a binary choice variable coded 0 if a country has not yet introduced a social pension or a family support scheme and 1 in the year when a country introduced the respective program. By now, around 50 LMIC (low- and middle-income countries) have a social pension in place, and a comparable number of countries are provided with a family support scheme. In the BTSCS models the countries are only considered until the event happens. Once a specific program has been introduced, the country is excluded from the analysis of the respective program. I estimate logit equations using a standard maximum likelihood procedure. Ordinary probit or logit rests on the assumption that the observations are temporally independent. However, the probability of introducing social assistance is not equal at any point in time but increases over time. Therefore, ordinary probit or logit would be misleading and the standard errors underestimated. I follow the procedure suggested by Beck et al. (1998) in order to deal with time dependence. Beck et al. (1998) show that binary time-series cross-section data is identical with grouped duration data. They suggest estimating the models including cubic splines, as natural cubic splines capture the time dependence. The estimated coefficients of the cubic splines can be used to trace the path of duration dependence. In comparison to time dummies, cubic splines have the advantage of providing a more parsimonious strategy. I alternatively checked t, t2 and t3 as a cubic polynomial approximation in the estimations (Carter and Signorino, 2010). Moreover, robust standard errors clustered by country are used.

In the empirical analyses the influence of the British and French colonial legacy as a central independent variable is captured by including dummies for British or French colonies. Moreover, I include the real GDP per capita (log.) as a control variable (Maddison Project Database 2018) to measure a nation’s level of economic development. In line with functionalist theories, it is expected that there is a positive relationship between affluence and the introduction of social protection (Wilensky 1975). Moreover, I include the level of democracy, which in many studies is assumed to drive the introduction and emergence of social assistance. I use the polity index which ranges from −10 (autocracy) to 10 (full democracy) (Marshall et al. 2014). A further key variable is the dependency ratio, that is, the number of people above 65 and below 15 in relation to the total working-age population (World Bank 2015). A high dependency ratio should be reflected in a strong demand for noncontributory social pensions and family support schemes. Additionally, it can be expected that the colonial legacy diminishes over time after gaining independence. Hence the longer a country is independent, the higher is the probability that it is able to follow the recent policy trend. Furthermore, the level of globalization, measured as the total of exports and imports in relation to the GDP, might exhibit a negative influence on the introduction of social assistance programs, due to the competitive pressure arising from embeddedness in the international market.Footnote 4 As mentioned above, international organizations such as the ILO strongly promote the introduction of social assistance programs. I therefore include a dummy capturing whether a country is an ILO member or not. Furthermore, it is checked for ethnic fractionalization (Alesina et al. 2003). It is argued that “ethnic diversity has led to social polarization and entrenched interest groups in Africa and thereby should decrease the likelihood that a country introduces a universal noncontributory social protection scheme” (Englebert 2000, 9; Alesina et al. 2003).

In the cross-section analyses, all independent variables are calculated as an average across the ten years prior to the information of the dependent variable. In the BTSCS estimation I additionally check regional diffusion processes by including a spatial lag capturing the number of countries with a respective scheme that share a common border with the focal country. Basic descriptive statistics of the main variables included can be found in the appendix.

Explaining the Existence of Social Assistance in the Global South

Did the spread of social assistance differ by colonial sphere? Table 6.1 shows the empirical results of the logit regressions. In models 1 and 2 the introduction of social pensions is used as a dependent variable, and in models 3 and 4 it is family support schemes. The first and the third model test the influence of the British colonial legacy, and the second and the fourth model test the French colonial influence. Odds ratio are displayed.

The results remarkably confirm the main hypothesis that the likelihood whether a country has a social pension or an unconditional family support program is highly influenced by the colonial legacy. When looking at the results for social pensions, the probability of a former British colony having a social pension is almost 7 times higher than in all other LMIC. On the other hand, being a former French colony decreases the likelihood of having a social pension scheme by 89.2 percentage points. The strong social insurance tradition, especially with regard to retirement schemes, seems to heavily influence the contemporary choices for social policy-making. The situation is slightly different with regard to family support schemes. Even though former French colonies are also less likely to implement these programs, the influence is less hampering than in the case of social pensions. This reflects the importance of family support schemes in the tradition of the French welfare state. In the case of the British colonies, the positive role of the colonial legacy for the introduction of social pensions is not observable with regard to unconditional family support programs. This represents the low British emphasis on family policies and the lacking tradition regarding this scheme.

The results regarding the level of democracy are also interesting. In line with previous research, democratic institutions seem to push the introduction of social pensions. The likelihood of having a social pension increases by about 17 percentage points with a one unit increase in the polity index. However, the positive influence is only observable in the case of social pensions, but not in the case of family support schemes. Interestingly, the effect of democracy differs by colonial sphere. To illustrate the conditional effect of the colonial heritage, I calculated the effect of the regime type on the likelihood of introducing social pensions in dependence of the colonial legacy. Figure 6.2 displays the effect of democratic institutions for former French (right figure) and former British colonies (left figure), each in comparison to the rest of the sample. In the right figure it can be observed that an increase from the lowest possible value for the polity index (−10) to the highest one (10) only slightly enhances the likelihood of a former French colony (right figure, solid line) to have a social pension scheme (by around 15 percentage points) in contrast to an estimated increase for all other LMIC by 60 percentage points (right figure, dash line). In the case of former British colonies (left figure, solid line), the marginal effect of democratic institutions on the predicted probability of having a social pension is similar to the non-British colonies (left figure, dash line). However, former British colonies have a higher probability of having a social pension schemes than all other LMIC, independently of the level of democracy.

Table 6.2 shows the results of the binary time-series cross-section analyses.

The results of the BTSCS (binary time-series cross-section) models, which take the time dimension into account, confirm the results of the cross-section analyses. Being a former French colony decreases the likelihood of introducing a social pension by around 90 percentage points. By contrast, ex-colonies of the British Empire introduce social pension schemes very early in comparison to all other LMIC (besides of French ex-colonies). More democratic countries are more likely to adopt social pension schemes, while this relationship does not hold in the case of family support schemes. The consideration of the time dimension allows testing for regional diffusion processes. The results strongly corroborate the importance of regional diffusion. The likelihood that a country introduces social assistance increases with the number of surrounding countries with the respective scheme.

Conclusion

Social assistance is one of the most recent policy trends in the Global South, raising many expectations. Since social assistance is not based on individual contributions, it is assumed to be an effective instrument for reducing poverty and inequality and for expanding social protection to the most vulnerable groups of society. Indeed, there is some evidence of these positive effects of social assistance. This evidence motivates international organizations such as the ILO or the World Bank to promote the introduction of social assistance in developing countries.

When explaining the recent trend of social assistance, studies have particularly emphasized the role of democratic institutions. However, I have argued that this only holds in the case of certain institutional preconditions which depend on the colonial legacy. Colonial empires differed in their imperial strategies and in their notions on the role of the state regarding social protection. These differences have influenced early social protection legislation and institutions but have still consequences for today’s social policy-making.

By analyzing the spread of social pensions and unconditional family support programs as two of the most important social assistance schemes in LMIC in a quantitative framework, I can show that former British colonies are more likely to introduce social assistance than all other LMIC. This reflects the British Poor Law tradition and the decentralized imperial strategy of Britain, which have led to a very early diffusion of ideas on social assistance across the Empire. In contrast, in the early days of social protection in the Global South all former French colonies implemented social insurances in line with the strong social insurance tradition that characterizes the French welfare state. A shift from insurance-based social protection to tax-financed noncontributory social assistance would require a complete restructuring of existing institutions and would come along with tremendous costs. As a consequence, former French colonies did not follow the recent trend of introducing social assistance programs. The French colonial legacy even outweighs the positive influence of democratic institutions for which many studies have produced evidence. These findings show that it is very important to take the colonial legacy into account when analyzing early but also contemporary social protection in the Global South. The results also demonstrate that it is not sufficient to simply promote a specific strategy of social protection but rather to consider the historical context to come to a better understanding of the causes and consequences of early and contemporary social protection. However, the results do not imply that national conditions are not important for policy-making but rather that domestic conditions unfold different effects depending on the historical context of a country.

Notes

- 1.

Social assistance and noncontributory social protection are interchangeably used in this chapter.

- 2.

CCTs (conditional cash transfers) are not considered, as—unlike unconditional programs—they are conditional to investments in education or health. Additionally, they are more heterogeneous for example, regarding the specific target they aim at and the policy field they belong to. They therefore follow a slightly different logic and are not easily comparable with the two other programs analyzed in this contribution.

- 3.

Other central colonizers such as Spain abandoned their imperial projects already in the first half of the nineteenth century, and therefore before social protection was put on the global agenda and the labor question became urgent in the dependent territories. Further imperial nations such as Belgium, Portugal, Italy or Germany had only a few colonies or maintained their colonies for a much shorter duration, which is why a statistical analysis on their influence would be less informative.

- 4.

However, it might also push countries to meet international standards and introduce basic social protection programs.

References

Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson. 2001. The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation. American Economic Review 91: 1369–1401.

Alesina, Alberto, Arnaud Devleeschauwer, William Easterly, Sergio Kurlat, and Romain Wacziarg. 2003. Fractionalization. Journal of Economic Growth 8: 155–194.

Barrientos, Armando. 2011. Social Protection and Poverty. International Journal of Social Welfare 20: 240–249.

Beck, Nathaniel, Jonathan N. Katz, and Richard Tucker. 1998. Taking Time Seriously: Time-Series-Cross-Section Analysis with a Binary Dependent Variable. American Journal of Political Science 42: 1260–1288.

Béland, Daniel, and Randall Hansen. 2000. Reforming the French Welfare State: Solidarity, Social Exclusion and the Three Crises of Citizenship. West European Politics 23: 47–64.

Brooks, Sarah M. 2007. When Does Diffusion Matter? Explaining the Spread of Structural Pension Reforms across Nations. The Journal of Politics 69: 701–715.

———. 2015. Social Protection for the Poorest: The Adoption of Antipoverty Cash Transfer Programs in the Global South. Politics and Society 43: 551–582.

Carter, David B., and Curtis S. Signorino. 2010. Back to the Future: Modeling Time Dependence in Binary Data. Political Analysis 18: 271–292.

Cooper, Frederick. 1989. From Free Labor to Family Allowances: Labor and African Society in Colonial Discourse. American Ethnologist 16: 745–765.

———. 1996. Decolonization and African Society. The Labor Question in French and British Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dodlova, Marina, and Anna Giolbas. 2015. Regime Type, Inequality, and Redistributive Transfer in Developing Countries. GIGA Working Paper Series no. 273, May 2015.

Dodlova, Marina, Anna Giolbas, and Jann Lay. 2016. Non-Contributory Social Transfer Programmes in Developing Countries: A New Data Set and Research Agenda. GIGA Working Paper Series no. 290, August 2016.

Echenberg, Myron J. 1975. Paying the Blood Tax: Military Conscription in French West Africa, 1914–1929. Canadian Journal of Political Science 9: 171–192.

Eckert, Andreas. 2004. Regulating the Social: Social Security, Social Welfare and the State in Late Colonial Tanzania. The Journal of African History 45: 467–489.

Englebert, Pierre. 2000. Pre-Colonial Institutions, Post-Colonial States, and Economic Development in Tropical Africa. Political Research Quarterly 53: 7–36.

Fieldhouse, David K. 1967. The Colonial Empires: A Comparative Survey from the Eighteenth Century. New York: Delacorte Press.

Grier, Robin M. 1999. Colonial Legacies and Economic Growth. Public Choice 98: 317–335.

HelpAge International. 2017. Social Pension Database. http://www.pension-watch.net/social-pensions-database/social-pensions-database%2D%2D/.

Iliffe, John. 1987. The African Poor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

International Labour Organisation. 2017. World Social Protection Report. Building Economic Recovery, Inclusive Development and Social Justice. Geneva: ILO.

Kaufmann, Franz-Xaver. 2013. Variations of the Welfare State: Great Britain, Sweden, France and Germany between Capitalism and Socialism. Berlin: Springer.

Kott, Sandrine, and Joëlle Droux, eds. 2013. Globalizing Social Rights. The International Labour Organization and Beyond. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kpessa, Michael W., and Daniel Béland. 2013. Mapping Social Policy Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Policy Studies 34: 326–341.

Lange, Matthew K. 2004. British Colonial Legacies and Political Development. World Development 32: 905–922.

Leisering, Lutz, and Armando Barrientos. 2013. Social Citizenship for the Global Poor? The Worldwide Spread of Social Assistance. International Journal of Social Welfare 22: 50–67.

Lindsay, Lisa A. 1999. Domesticity and Difference: Male Breadwinners, Working Women, and Colonial Citizenship in the 1945 Nigerian General Strike. The American Historical Review 104: 783–812.

MacLean, Lauren. 2002. Constructing a Social Safety net in Africa: An Institutionalist Analysis of Colonial Rule and State Social Policies in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire. Studies in Comparative International Development 37: 64–90.

Maddison Project Database. 2018. Bolt, Jutta, Robert Inklaar, Herman de Jong, and Jan Luiten van Zanden. Rebasing ‘Maddison’: New Income Comparisons and the Shape of Long-run Economic Development. Maddison Project Working paper 10.

Mahoney, James. 2010. Colonialism and Postcolonial Development: Spanish America in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marshall, Monti G., Ted R. Gurr, and Keith Jaggers. 2014. Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800–2012. Dataset Users’ Manual.

Maul, Daniel. 2012. Human Rights, Development and Decolonization: The International Labour Organization, 1940–1970. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Midgley, James. 1984a. Diffusion and Development of Social Policy: Evidence from the Third World. Journal of Social Policy 13: 167–184.

———. 1984b. Poor Law Principles and Social Assistance in the Third World: A Study of the Perpetuation of Colonial Welfare. International Social Work 27: 19–29.

Midgley, James, and David Piachaud, eds. 2011. Colonialism and Welfare. Social Policy and the British Imperial Legacy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Orr, Charles A. 1966. Trade Unionism in Colonial Africa. Journal of Modern African Studies 4: 65–81.

Overbye, Einar. 2005. Extending Social Security in Developing Countries: A Review of Three Main Strategies. International Journal of Social Welfare 14: 305–314.

Palier, Bruno. 2000. “Defrosting” the French Welfare State. West European Politics 23: 113–136.

Pedersen, Susan. 1993. Family, Dependence, and the Origins of the Welfare State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Plant, Roger. 1994. Labour Standards and Structural Adjustment. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Schmitt, Carina. 2015. Social Security Development and the Colonial Legacy. World Development 70: 332–342.

Schmitt, Carina, Hanna Lierse, Herbert Obinger, and Laura Seelkopf. 2015. The Global Emergence of the Welfare State: Explaining Social Policy Legislation, 1820–2013. Politics and Society 43: 503–524.

Seekings, Jeremy. 2008. Welfare Regimes and Redistribution in the South. In Divide and Deal: The Politics of Distribution in Democracies, ed. Ian Shapiro, Peter A. Swenson, and Daniela Donno. New York: New York University.

———. 2011. British Colonial Policy, Local Politics, and the Origins of the Mauritian Welfare State, 1936–1950. Journal of African History 52: 157–177.

———. 2013. Social Policy. In Routledge Handbook of African Politics, ed. Nic Cheeseman, David Anderson, and Andrea Scheibler. London: Routledge.

Surender, Rebecca. 2013. The Role of Historical Contexts in Shaping Social Policy in the Global South. In Social Policy in a Developing World, ed. Rebecca Surender and Robert Walker. Edward Elgar: Northampton.

Wilensky, Harold L. 1975. The Welfare State and Equality. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Williamson, John B., and Fred C. Pampel. 1991. Ethnic Politics, Colonial Legacy, and Old Age Security Policy: The Nigerian Case in Historical and Comparative Perspective. Journal of Aging Studies 5: 19–44.

World Bank. 2015. World Development Indicators. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Schmitt, C. (2020). The Colonial Legacy and the Rise of Social Assistance in the Global South. In: Schmitt, C. (eds) From Colonialism to International Aid. Global Dynamics of Social Policy . Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38200-1_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38200-1_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-38199-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-38200-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)