Abstract

This article presents a new method for the production of disposable carbon fiber formworks for the casting of reinforced concrete columns. The desired three-dimensional object can be made by the robotic hot wire cutting of polystyrene, thus generating the shape around which the carbon fiber is deposited. The manufacturing technique is the so-called filament winding, where the polystyrene shape—obtained through hotwire cutting—is wrapped in fiber tape and then undergoes a curing process, which returns the carbon geometry in solid form. At the end of the process, the final piece of carbon is obtained by dissolving the positive polystyrene mold with a solvent. This gives rise to a production method capable of creating geometries that cannot be achieved by other means. The choice of creating disposable fiber formworks for concrete castings has considerable advantages: the possibility of creating structural elements with complex geometries that cannot be obtained by means of traditional formworks or other materials; saving of time in the casting phase and the advantage of not having the de-casting phase; facilitating the positioning of formworks and other structural elements thanks to the reduced weight of the material; the possibility of having always different geometries and a finish with a high aesthetic value and functional performance. The combination of concrete and carbon fibers offers above all considerable advantages from the structural point of view. The formwork not only has the function of giving shape to the finished element but also becomes a collaborator for static purposes. If used for pillars, the carbon fiber formwork has the function of a hoop, which makes it possible to obtain columns with the same static capacity but with lower sections and the elimination of the transversal reinforcement.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Choice of Materials

Among the possible materials for the construction of the disposable formwork, the choice fell on the carbon fiber both for structural reasons related to the lightness of the material and its high mechanical resistance to traction and for the resistance to temperature changes and the effect of chemical agents. To achieve an effective rim, in fact, a high degree of rigidity is required and carbon has the highest elastic modulus among the fibers on the market. This material is also resistant to the alkaline environment typical of concrete. It was decided to combine carbon with a thermosetting matrix, particularly epoxy; compared to a thermoplastic matrix, the former guarantees better mechanical characteristics, together with a more effective method of applying the fibers. The most suitable and economical production process for the deposition of the fiber on molds is that of filament winding. To make molds for molds that are always different through digital manufacturing methods, it is necessary to use an inexpensive material that is easy to work with, sufficiently resistant to the compression applied during the winding phase of the fibers and inert against resins and carbon fiber. Remaining among the most popular and well-known materials in the building industry, extruded polystyrene was chosen. This material can also be dissolved, thus offering the possibility of making molds for non-extractable geometries. This allows us to overcome one of the biggest limits of filament winding, that is the possibility to realize only shapes that can be removed from the mold at the end of the production (Figs. 1 and 2).

2 Innovation in Design, Process, and Product

Designing a disposable formwork means designing the final geometry of the pillar. The pillar is a three-dimensional structural element with a much larger size than the other two; its role is to support the structure above, withstand transverse loads and transmit the forces to the underlying structures or foundations. The section of a traditional pillar is generally square, rectangular or circular, depending on functional, physical, and production reasons. The use of these forms in the past also had other reasons: in the absence of automatic calculators, simple geometries with a constant section facilitated the determination of all the data necessary for the design, such as volume, weight, barycentric axes, moments of inertia and modules of resistance. These problems can now be overcome thanks to the use of three-dimensional modeling programs, together with finite element analysis software, which allows you to analyze in detail any type of geometry. It is therefore easy to design complex geometries.

Robotic manufacturing also makes it economically viable to produce such geometries.

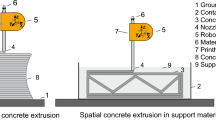

In this context, the idea was born of exploiting robotic manufacturing for the construction of formworks that allow the actual implementation of what was designed. The process used is that of robotic cutting of polystyrene with hot wire; a process that is up to a hundred times faster than numerical control milling. The molds are machined using grooved surfaces and are composed of two halves to facilitate fixing on the rotating axis of the lathe during the filament winding phase (Fig. 3).

The winding of the mold takes place by applying the first layer of epoxy resin in the form of adhesive tape and the subsequent deposition of the pre-impregnated carbon fiber tape with moderate and constant inclination, so as to cover the surface uniformly without creating wrinkles in the material. The molds are covered by two windings, each one continuous for the whole length of the piece, made with the same inclination but starting from the two opposite ends of the block, thus creating an opposite winding (Fig. 4).

Once the winding phase is completed, the mold is removed from the axis of the lathe and put into the autoclave. The temperature, pressure, and care time depend on the mix of materials used, the size and number of coils made. The low resistance of the extruded polystyrene to high temperatures requires low-temperature cycles in the autoclave, with a consequent lengthening of the treatment time. To obtain the disposable formwork from the semi-finished product obtained, it is necessary to eliminate the polystyrene mold. Working with complex geometries, it is not possible to remove the mold from the carbon body. The acetone’s ability to dissolve polystyrene is therefore exploited. In a few minutes, the reduction in the volume of the mold—due to the contact between acetone and polystyrene—is sufficient to allow the extraction of the mold and thus obtain the hollow shape of the disposable fiber formwork. The formwork is thus ready for casting (Fig. 5).

Laboratory tests show that, in terms of cross-section, a wheeled concrete specimen with a disposable formwork made with this system offers an ultimate compressive strength almost three times greater than an unwheeled specimen (97 tons compared to 36 tons).

In short, the proposed method expresses the desire to create unique elements that encompass the rationality of engineering and the expressiveness of architecture (Fig. 6).

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted by Pierpaolo Ruttico and Massimo Rota (Indexlab - Politecnico di Milano), in collaboration with Federico Carmona (Carmon@carbon) and with the support of Francesco Braghin (Polimi - Mecc).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ruttico, P., Pizzi, E. (2020). Development of a System for the Production of Disposable Carbon Fiber Formworks. In: Daniotti, B., Gianinetto, M., Della Torre, S. (eds) Digital Transformation of the Design, Construction and Management Processes of the Built Environment. Research for Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33570-0_20

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33570-0_20

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-33569-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-33570-0

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)