Summary

Climate change is becoming an existential threat with warming in excess of 2 °C within the next three decades and 4–6 °C within the next several decades. Warming of such magnitudes will expose as many as 75% of the world’s population to deadly heat stress in addition to disrupting the climate and weather worldwide. Climate change is an urgent problem requiring urgent solutions. This chapter lays out urgent and practical solutions that are ready for implementation now, will deliver benefits in the next few critical decades, and place the world on a path to achieving the long-term targets of the Paris Agreement. The approach consists of four building blocks and three levers to implement ten scalable solutions described in this chapter. These solutions will enable society to decarbonize the global energy system by 2050 through efficiency and renewables, drastically reduce short-lived climate pollutants, and stabilize the warming well below 2 °C both in the near term (before 2050) and in the long term (after 2050). The solutions include an atmospheric carbon extraction lever to remove CO2 from the air. The amount of CO2 that must be removed ranges from negligible (if the emissions of CO2 from the energy system and short-lived climate pollutants have started to decrease by 2020 and carbon neutrality is achieved by 2050) to a staggering one trillion tons (if the carbon lever is not pulled and emissions of climate pollutants continue to increase until 2030).

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Climate change solutions

- Carbon neutrality

- Short lived climate pollutants

- Carbon extraction

- Societal transformation

Bending the Curve: Four Building Blocks, Three Levers, and Ten Solutions

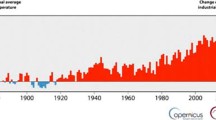

The Paris Agreement is an historic achievement. For the first time, effectively all nations have committed to limiting their greenhouse gas emissions and taking other actions to limit global temperature change (Fig. 25.1). Specifically, 197 nations have agreed to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels” and achieve carbon neutrality in the second half of this century (UNFCCC, 2015).

The climate has already warmed by 1 °C (IPCC, 2013). The problem is running ahead of us, and under current trends we will likely reach 1.5 °C in less than 15 years (Xu and Ramanathan 2017) and surpass the 2 °C guardrail by midcentury with a 50% probability of reaching 4 °C by the end of the century (IPCC, 2014b; Ramanathan & Feng, 2008; World Bank, 2013). Warming in excess of 3 °C is likely to be a global catastrophe for three major reasons:

-

Warming in the range of 3–5 °C is suggested as the threshold for several tipping points in the physical and geochemical systems; warming of about 3 °C carries a >40% probability of crossing over multiple tipping points, while warming close to 5 °C increases the probability to nearly 90% in comparison with baseline warming of less than 1.5 °C, which carries just over a 10% probability of exceeding any tipping point (Ramanathan & Feng, 2008).

-

Health effects of such warming are emerging as a major if not dominant source of concern. Warming of 4 °C or more will expose more than 70% of the population—that is, about seven billion people by the end of the century—to deadly heat stress (Mora et al., 2017) and expose about 2.4 billion to vector-borne diseases such as dengue, chikungunya, and Zika virus, among others (Proestos et al., 2015; Ramanathan et al., 2017; WHO, 2016; Watts et al., 2015).

-

Ecologists and paleontologists have postulated that warming in excess of 3 °C, accompanied by increased acidity of the oceans with the buildup of CO2, could become a major causal factor for exposing more than 50% of all species to extinction. Twenty percent of species are in danger of extinction now due to population increase, habitat destruction, and climate change (Dasgupta et al., 2015).

The good news is that there may still be time to avert such catastrophic changes. The Paris Agreement and supporting climate policies must be strengthened substantially within the next 5 years to bend the emissions curve down faster, stabilize the climate, and prevent catastrophic warming. To the extent those efforts fall short, societies and ecosystems will be forced to contend with substantial needs for adaptation—a burden that will fall disproportionately on the poorest three billion people, who are least responsible for causing the climate change problem (Pope Francis, 2015).

Here we propose an emissions pathway and a policy roadmap with a realistic and reasonable chance of limiting global temperatures to safe levels and preventing unmanageable climate change—an outline of specific science-based policy pathways that serve as the building blocks for a three-lever strategy that could limit warming to well under 2 °C. The projections and the emission pathways proposed in this summary are based on a combination of published recommendations and new model simulations conducted by the authors of this study (see Fig. 25.2).

Projected warming in four different scenarios from the preindustrial era to 2100, adopted from Xu and Ramanathan (PNAS, Vol. 114. No. 9, PP 10315–10323; Xu & Ramanathan, 2017). The warming is shown in terms of probability distribution instead of a single value because of uncertainties in climate feedbacks, which could make the warming greater or lesser than the central value shown by the peak probability density value. The three curves on the right side indicated by BL (for baseline) denote projected warming in the absence of climate policies. The baseline with a confidence interval of 80% (BL (CI-80%)) is for the scenario in which the energy intensity (the ratio of energy use to economic output) of the economy decreases by 80% in comparison with its value in 2010. For BL (CI-50%), the energy intensity decreases by only 50%. These scenarios bound the energy growth scenarios considered by Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Working Group III (IPCC-WGIII) (2014). The extreme right curve, BL (CI-50% and carbon feedbacks), includes the carbon cycle feedback due to the warming caused by the BL (CI-50%) case. The carbon cycle feedback adopts IPCC-recommended values for the reduction in CO2 uptake by the oceans as a result of the warming, the release of CO2 by melting permafrost, and the release of methane by wetlands. The green curve adopts the four building blocks and the three levers proposed in this chapter. There are four mitigation steps: (1) Improve the energy efficiency and decrease the energy intensity of the economy by as much as 80% from its 2010 value. This step alone will decrease the warming by 0.9 °C (1.6 °F) by 2100. (2) Bend the carbon emission curve further by switching to renewables before 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality within three decades. This step will decrease the warming by 1.5 ºC (2.7 ºF) by 2100. (3) Bend the short-lived climate pollutants curve, beginning in 2020, following the actions California has demonstrated. This step will decrease the warming by as much as 1.2 ºC (2.2 ºF) by 2100. (4) In addition, extract as much as 1 trillion tons (about half of what we have emitted so far) from the atmosphere by 2100. This step will decrease the warming by as much as 0.3 ºC to 0.6 ºC (0.5 ºF to 1 ºF). The 50% probable warming values in the four scenarios are (from left to right) 1.4 °C (2.5 °F), 4.1 °C (7.4 °F), 5 °C (9 °F), and 5.8 °C (10.4 °F), respectively. There is a 5% probability that the warming in the four scenarios could exceed (from left to right) 2.2 °C (4 °F), 5.9 °C (10.6 °F), 6.8 °C (12.2 °F), and 7.7 °C (14 °F), respectively. The risk categories shown at the top largely follow Xu and Ramanathan (2017), with slight modifications. Following the IPCC and Xu and Ramanathan (2017), we denote warming in excess of 1.5 °C as dangerous. Following the burning embers diagram from the IPCC as updated by O’Neill et al. (2017), warming in excess of 3 °C is denoted as catastrophic. We invoke recent literature on the health effects >4 °C warming, impacts including mass extinction with >5 °C warming, and a projected collapse of natural systems with warming in excess of 3 °C, to denote >5 °C warming as exposing the global population to existential threats

We have framed the plan in terms of four building blocks and three levers (Fig. 25.1), which would be implemented through ten solutions. The first building block would be full implementation of the nationally determined mitigation pledges under the Paris Agreement of the United Nations (UN) Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). In addition, several sister agreements that provide targeted and efficient mitigation must be strengthened. Sister agreements include the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol to phase down hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), efforts to address aviation emissions through the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and maritime black carbon emissions through the International Maritime Organization (IMO), and the commitment by the eight countries of the Arctic Council to reduce black carbon emissions by up to 33% (Arctic Council, 2017a, 2017b; ICAO, 2016; IMO, 2015; UNEP, 2016a). There are many other complementary processes that have drawn attention to specific actions on climate change, such as the Group of Twenty (G20), which has emphasized reform of fossil fuel subsidies, and the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC). HFC measures, for example, can avoid as much as 0.5 °C of warming by 2100 through the mandatory global phasedown of HFC refrigerants within the next few decades, and substantially more through parallel efforts to improve the energy efficiency of air conditioners and other cooling equipment, potentially doubling this climate benefit (Shah, Wei, Letschert, & Phadke, 2015; Xu et al. 2013; Zaelke, Andersen, & Borgford-Parnell, 2012).

For the second building block, numerous subnational and city-scale climate action plans have to be scaled up. One prominent example is California’s Under 2 Coalition, signed by over 177 jurisdictions from 37 countries in six continents, covering a third of the world economy. The goal of this memorandum of understanding is to catalyze efforts in many jurisdictions that are comparable with California’s target of 40% reductions in CO2 emissions by 2030 and 80% reductions by 2050—emission cuts that, if achieved globally, would be consistent with stopping warming at about 2 °C above preindustrial levels (Under2MOU, 2017). Another prominent example is the climate action plans devised by over 50 cities and 65 businesses around the world, aiming to cut emissions by 30% by 2030 and 80–100% by 2050. There are concerns that the carbon-neutral goal will hinder economic progress; however, real-world examples from California and Sweden since 2005 offer evidence that economic growth can be decoupled from carbon emissions, and the data for CO2 emissions and gross domestic product (GDP) reveal that growth in fact prospers with a green economy (Saha & Muro, 2016).

The third building block consists of two levers that we need to pull as hard as we can: one for drastically reducing emissions of short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) , beginning now and completing this by 2030, and the other for decarbonizing the global energy system by 2050 through efficiency and renewables. Pulling both levers simultaneously could keep the global temperature rise below 2 °C through the end of the century (Shindell et al., 2012, 2017; Shoemaker, Schrag, Molina, & Ramanathan, 2013). If we bend the CO2 emissions curve through decarbonization of the energy system such that global emissions have peaked in 2020, decrease steadily thereafter, and reach zero in 2050, there is less than a 20% probability of exceeding 2 °C warming (IPCC, 2013; Xu & Ramanathan, 2017). This call for bending the CO2 curve by 2020 is one key way in which this chapter’s proposal differs from the Paris Agreement, and it is perhaps the most difficult task of all those envisioned here. Many cities and jurisdictions are already on this pathway, thus demonstrating its scalability. Achieving carbon neutrality and reducing emissions of SLCPs would also drastically reduce air pollution globally, including air pollution in all major cities, thus saving millions of lives and over 100 million tons of crops lost to air pollution each year (Shindell et al., 2012). In addition, these steps would provide clean energy access for the world’s poorest three billion people, who are still forced to resort to nineteenth-century technologies to meet basic needs such as cooking (Dasgupta et al., 2015; IPCC, 2014a).

For the fourth and final building block, we are adding a third lever, ACE (atmospheric carbon extraction, also known as carbon dioxide removal (CDR)). This lever is added as insurance against unwanted surprises (due to policy lapses, mitigation delays, or nonlinear climate changes) and would require development of scalable measures for removing the CO2 already in the atmosphere. The amount of CO2 that must be removed will range from negligible (if the emissions of CO2 from the energy system and SLCPs have started to decrease by 2020 and carbon neutrality is achieved by 2050) to a staggering one trillion tons (if CO2 emissions continue to increase until 2030 and the carbon lever is not pulled until after 2030) (Xu & Ramanathan, 2017). This issue is raised because the NDCs (nationally determined contributions) accompanying the Paris Agreement would allow CO2 emissions to increase until 2030 (UNEP, 2016b). We call on economists and experts in political and administrative systems to assess the feasibility and cost effectiveness of reducing carbon and SLCP emissions beginning in 2020, in comparison with delaying it by 10 years and then being forced to pull the third lever to extract one trillion tons of CO2 from the atmosphere.

The fast mitigation plan of requiring emissions reductions to begin by 2020—which means that many countries already need to be cutting their emissions now—is urgently needed to limit the warming to well under 2 °C. Climate change is not a linear problem. Instead, we are facing nonlinear climate tipping points that can lead to self-reinforcing and cascading climate change impacts (Lenton et al., 2008). Tipping points and self-reinforcing feedbacks are wild cards that are more likely with increased temperatures, and many of the potential abrupt climate shifts could happen as warming goes from 1.5 °C in 15 years to 2 °C by 2050, with the potential to push us well beyond any possibility of achieving Paris Agreement goals (Drijfhout et al., 2015).

Ten Scalable Solutions to Bend the Curve

The four building blocks and the three levers require global mobilization of human, financial, and technical resources. For the global economy and society to achieve such rapid reductions in SLCPs by 2030 and carbon neutrality and climate stability by 2050, we will need multidimensional and multisectoral changes and modifications to bend the warming curve, which are grouped under the ten scalable solutions listed below. We have adapted these solutions with some modifications from a book chapter titled “Bending the Curve,” written by 50 researchers from the University of California system (Ramanathan et al., 2015). The ten solutions are grouped under six clusters as listed below:

Science Pathways Cluster

-

1.

Show that we can bend the warming curve immediately by reducing SLCPs and long-term by replacing current fossil fuel energy systems with carbon-neutral technologies.

Societal Transformation Cluster

-

2.

Foster a global culture of climate action through coordinated public communication and education at local to global scales.

-

3.

Build an alliance among science, religion, health care, and policy to change behavior and garner public support for drastic mitigation actions.

Governance Cluster

-

4.

Build upon and strengthen the Paris Agreement , and strengthen sister agreements like the Montreal Protocol’s Kigali Amendment to reduce HFCs.

-

5.

Scale up subnational models of governance and collaboration around the world to embolden and energize national and international action. California’s Under 2 Coalition and the climate action plans devised by over 50 cities are prime examples.

Market-Based and Regulation-Based Cluster

-

6.

Adopt market-based instruments to create efficient incentives for businesses and individuals to reduce CO2 emissions.

-

7.

Target direct regulatory measures—such as rebates and efficiency and renewable energy portfolio standards—for high-emissions sectors not covered by market-based policies.

Technology Cluster

-

8.

Promote immediate and widespread use of mature technologies such as photovoltaics, wind turbines, biogas, geothermal energy, batteries, hydrogen fuel cells, electric light-duty vehicles, and more efficient end-use devices, especially in lighting, air conditioning and other appliances, and industrial processes. Aggressively support and promote innovations to accelerate the complete electrification of energy and transportation systems and improve building efficiency.

-

9.

Immediately make maximum use of available technologies combined with regulations to reduce methane emissions by 50%, reduce black carbon emissions by 90%, and eliminate hydrofluorocarbons with high global-warming potential (high-GWP HFCs) ahead of the schedule in the Kigali Amendment while fostering energy efficiency.

Atmospheric Carbon Extraction Cluster

-

10.

Regenerate damaged natural ecosystems and restore soil organic carbon. Urgently expand research and development of atmospheric carbon extraction, along with carbon capture, utilization, and storage.

Concluding Remarks: Where Do We Go from Here?

A massive effort will be needed to stop warming at 2 °C, and time is of the essence. With unchecked business-as-usual emissions, global warming has a 50% likelihood of exceeding 4 °C and a 5% probability of exceeding 6 °C in this century, raising existential questions for most, but especially the poorest three billion people. Dangerous to catastrophic impacts on the health of people (including generations yet to be born), on the health of ecosystems, and on species extinction have emerged as major justifications for keeping climate change well below 2 °C, although we must recognize that the intrinsic uncertainties in climate and social systems make it hard to pin down exactly the level of warming that will trigger possibly catastrophic impacts. To avoid these consequences, we must act now, and we must act fast and effectively. This chapter sets out a specific plan for reducing climate change in both the near and long terms. With aggressive urgent actions, we can protect ourselves. Acting quickly to prevent catastrophic climate change by decarbonization will save millions of lives, trillions of dollars in economic costs, and massive suffering and dislocation of people around the world. This is a global security imperative, as it can avoid the migration and destabilization of entire societies and countries, and reduce the likelihood of environmentally driven civil wars and other conflicts.

We must address everything from our energy systems to our personal choices to reduce emissions to the greatest extent possible. We must redouble our efforts to invent, test, and perfect systems of governance so that the large measure of international cooperation needed to achieve these goals can be realized in practice. The health of people for generations to come and the health of ecosystems crucially depend on an energy revolution beginning now that will take us away from fossil fuels and toward the clean renewable energy sources of the future. It will be nearly impossible to achieve other critical social goals—for example, the UN’s Agenda 2030 and Sustainable Development Goals—if we do not make immediate and profound progress in stabilizing the climate, as we are outlining here.

Fortunately, there is momentum behind climate mitigation. Twenty-four countries have already embarked on a carbon-neutral pathway, and there are numerous living laboratories, including 53 cities, many universities around the world, and the state of California. These laboratories have already created eight million jobs in the clean energy industry; they have also shown that emissions of greenhouse gases and air pollutants can be decoupled from economic growth. We have a long way to go and very little time to achieve carbon neutrality. We need institutions and enterprises that can accelerate this bending by scaling up the solutions that are being proven in the living laboratories. We have less than a decade to put these solutions in place around the world to preserve nature and our quality of life for generations to come. The time is now.

References

Arctic Council (2017a). Fairbanks declaration. Tromsø, Norway: Artic Council.

Arctic Council (2017b). Expert group on black and carbon methane: Summary of Progress and recommendations. Tromsø, Norway: Artic Council.

Carbon Neutrality Coalition welcomes new members, pledges renewed ambition at UN Climate Action Summit (23 September 2019), https://www.carbon-neutrality.global/carbon-neutrality-coalition-welcomes-new-members-pledges-renewed-ambition-at-un-climate-action-summit/

Dasgupta, P., Ramanathan, V., Raven, P., Sorondo, Mgr M., Archer, M., Crutzen, P. J., et al. (2015). Climate change and the common good: A statement of the problem and the demand for transformative solutions. Vatican, Rome: The Pontifical Academy of Sciences and the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences.

Drijfhout, S., Bathiany, S., Beaulieu, C., Brovkin, V., Claussen, M., Huntingford, C., et al. (2015). Catalogue of abrupt shifts in intergovernmental panel on climate change climate models. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112, E5777–E5786.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2013). Climate change 2013: The physical science basis: Working group I contribution to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2014a). Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability: Working group II contribution to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Geneva: IPCC.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2014b). Climate change 2014: Synthesis report: Contribution of working groups I, II, and III to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Geneva: IPCC.

International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) (2016). Historic agreement reached to mitigate international aviation emissions. Montreal: ICAO. Press Release.

International Maritime Organization (IMO) (2015). Investigation of appropriate control measures (Abatement technologies) to reduce black carbon emissions from international shipping. London: IMO.

Lenton, T. M., Held, H., Kriegler, E., Hall, J. W., Lucht, W., Rahmstorf, S., et al. (2008). Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105, 1786–1793.

Mora, C., Dousset, B., Caldwell, I. R., Powell, F. E., Geronimo, R. C., Bielecki, C. R., et al. (2017). Global risk of deadly heat. Nature Climate Change, 7, 501–506.

O’Neill, B. C., Oppenheimer, M., Warren, R., Hallegatte, S., Kopp, R. E., Pörtner, H. O., (2017). IPCC reasons for concern regarding climate change risks. Nature Climate Change, 7, 28–37.

Pope Francis. (2015). Praise Be To You Laudato Si: On care for our common home. Vatican City, Libreria Editrice Vaticana. ISBN 978-1-68149-677-2.

Proestos, Y., Christophides, G. K., Ergüler, K., Tanarhte, M., Walkdock, J., & Lelieveld, J. (2015). Present and future projections of habitat suitability of the Asian tiger mosquito, a vector of viral pathogens, from global climate simulation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, B: Biological Sciences, 370, 1–16.

Ramanathan, V., & Feng, Y. (2008). On avoiding dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system: Formidable challenges ahead. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(38), 14245–14250.

Ramanathan, V., Molina, M. J., Zaelke, D., Borgford-Parnell, N., Xu, Y., Alex, K., et al. (2017). Full: Well under 2 degrees celsius: Fast action policies to protect people and the planet from extreme climate change. Washington, DC: Institute of Governance and Sustainable Development.

Ramanathan, V., Allison, J. E., Auffhammer, M., Auston, D., Barnosky, A. D., Chiang, L., et al. (2015). Bending the curve: Executive summary. Oakland, CA: University of California. Retrieved on February 16, 2020 from https://uc-carbonneutralitysummit2015.ucsd.edu/_files/Bending-the-Curve.pdf

Saha D. & Muro M. (2016). Growth, carbon, and trump: State progress and drift on economic growth and emissions ‘decoupling’. Brookings report: Metropolitan Policy Program. Retrieved on February 16, 2020 from https://www.brookings.edu/research/growth-carbon-and-trump-state-progress-and-drift-on-economic-growth-and-emissions-decoupling/

Shah, N., Wei, M., Letschert, V., & Phadke, A. (2015). Benefits of leapfrogging to Superefficiency and low global warming potential refrigerants in air conditioning. Berkeley, CA: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Shindell, D., Kuylenstierna, J. C. I., Vignati, E., van Dingenen, R., Amann, M., Klimont, Z., et al. (2012). Simultaneously mitigating near-term climate change and improving human health and food security. Science, 335, 183–189.

Shindell, D., Borgford-Parnell, N., Brauer, M., Haines, A., Kuylenstierna, J. C. I., Leonard, S. A., et al. (2017). A climate policy path- way for near- and long-term benefits. Science, 356, 493–494.

Shoemaker, J. K., Schrag, D. P., Molina, M. J., & Ramanathan, V. (2013). What role for short-lived climate pollutants in mitigation policy? Science, 42, 1323–1324.

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (2015). Paris agreement. Bonn: UNFCCC.

Under2MOU (2017). The memorandum of understanding (MOU) on subnational global climate leadership. Subnational Global Climate Leadership Memorandum of Understanding. Retrieved on February 16, 2020 from https://www.theclimategroup.org/sites/default/files/under2-mou-with-addendum-english-a4.pdf

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2016a). Decision XXVIII/1: Further amendment of the Montreal protocol. Nairobi: UNEP.

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2016b). The emissions gap report 2016: A UNEP synthesis report. Nairobi: UNEP.

Watts, N., et al. (2015). Health and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. The Lancet, 386, 1861–1914.

World Bank. (2013). Turn down the heat: Why a 4°C warmer world must be avoided. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2016). Second global conference: Health and climate, conference conclusions and action agenda. Geneva: WHO.

Xu, Y., & Ramanathan, V. (2017). Well below 2°C: Mitigation strategies for avoiding dangerous to catastrophic climate changes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114, 10315–10323.

Xu, Y., Zaelke, D., Velders, G. J. M., & Ramanathan, V. (2013). The role of HFCs in mitigating 21st century climate change. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 13, 6083–6089.

Zaelke, D., Andersen, S. O., & Borgford-Parnell, N. (2012). Strengthening ambition for climate mitigation: The role of the Montreal protocol in reducing short-lived climate pollutants. Review of European Community and International Environmental Law, 21, 231–242.

Acknowledgements

This chapter is based on a full report, which can be accessed at: http://www.ramanathan.ucsd.edu/about/publications.php. The authors of the report include, in addition to the four authors of this chapter, the following: Ken Alex, Max Auffhammer, Paul Bledsoe, William Collins, Bart Croes, Fonna Forman, Örjan Gustafsson, Andy Haines, Reno Harnish, Mark Jacobson, Shichang Kang, Mark Lawrence, Damien Leloup, Tim Lenton, Tom Morehouse, Walter Munk, Romina Picolotti, Kimberly Prather, Graciela B. Raga, Eric Rignot, Drew Shindell, K. Singh, Achim Steiner, Mark Thiemens, David W. Titley, Mary Evelyn Tucker, Sachi Tripathi, David Victor, and Yangyang Xu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ramanathan, V., Molina, M.L., Zaelke, D., Borgford-Parnell, N. (2020). Well Under 2 °C: Ten Solutions for Carbon Neutrality and Climate Stability. In: Al-Delaimy, W., Ramanathan, V., Sánchez Sorondo, M. (eds) Health of People, Health of Planet and Our Responsibility. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31125-4_25

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31125-4_25

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-31124-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-31125-4

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)