Abstract

Conflict, from small-scale verbal disputes to large-scale violent war between nations, is one of the most fundamental elements of social life and a central topic in social science research. The main argument of this book is that computational approaches have enormous potential to advance conflict research, e.g., by making use of the ever-growing computer processing power to model complex conflict dynamics, by drawing on innovative methods from simulation to machine learning, and by building on vast quantities of conflict-related data that emerge at unprecedented scale in the digital age. Our goal is (a) to demonstrate how such computational approaches can be used to improve our understanding of conflict at any scale and (b) to call for the consolidation of computational conflict research as a unified field of research that collectively aims to gather such insights. We first give an overview of how various computational approaches have already impacted on conflict research and then guide through the different chapters that form part of this book. Finally, we propose to map the field of computational conflict research by positioning studies in a two-dimensional space depending on the intensity of the analyzed conflict and the chosen computational approach.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Conflict research

- Computational social science

- Agent-based models

- Geographic information systems

- Advancement of science

1 Introduction

From small-scale, non-violent disputes to large-scale war between nations, conflict is a central element of social life and has captivated the collective consciousness for millennia. In the fifth century B.C., Greek philosopher Heraclitus famously argued that “war is the father and king of all” and that conflict and strife between opposites maintains the world (Graham, 2019). Many centuries later, sociologist Georg Simmel would, in a similar vein, state that a society without conflict is “not only impossible empirically, but it would also display no essential life-process and no stable structure.” Social life, he posited, always “requires some quantitative relation of harmony and disharmony, association and dissociation, liking and disliking, in order to attain to a definite formation” (Simmel, 1904, p. 491). Many related assertions could be listed: From Marx’s depiction of all past history as class struggle (Marx and Engels, 2002) to Dahrendorf’s conflict theory, which put clashing interests between conflict groups at the heart of questions of social stability and change (Ritzer and Stepnisky, 2017), conflict is seen as the fundamental principle that shapes society and history: “Because there is conflict, there is historical change and development,” as Dahrendorf (1959, p. 208) put it.

Between societies, too, conflict has long been recognized as an essential force. In history and political philosophy, many of the classic works are centered on clashes and contentions: From Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War and Caesar’s De bello Gallico to Machiavelli’s Prince and Hobbes’s Leviathan, the issue of violent struggle for power between cities, states, and empires of all kinds has been key. From psychology to international relations, conflict is one of the central fields of inquiry, with classic work searching for the root causes of conflict at various levels of analysis, from individual human predispositions and behavior to the spread of ideology and structural relations between states to the anarchic international system (Waltz, 2001; Rapoport, 1995). In short, it is hard to imagine human life without conflict. Rather, conflict can be seen as a “chronic condition” (Rapoport, 1995, p. xxi) we have to live under. Consequently, it is unsurprising that efforts to understand conflict have been abundant. The statement that “more has been written on conflict than on any other subject save two: love and God” (Luce and Raiffa, 1989, as cited in Rapoport, 1995, p. xxi) puts this impression into words.Footnote 1

While this centrality of conflict for the human condition may be justification enough for the continued attempts of a range of scientific fields to better understand conflict in its manifold forms, another central motivation is, of course, the search for ways to control, reduce, or even prevent conflict. “Are there ways of decreasing the incidence of war, or increasing the chances of peace? Can we have peace more often in the future than in the past?” asks, for instance, Waltz (2001, p. 1). This desire to contribute to a saver, less conflictual world became most urgent in the face of total annihilation during the Cold War. As Rapoport (1995, p. xxii) put it, talking about nuclear war: “understand it we must, if we want a chance of escaping what it threatens.” An entire field, peace science, now aims at understanding the conditions for conflict resolution. Improving our understanding of the causes, structures, mechanisms, spatio-temporal dynamics, and consequences of conflict is thus an important goal of social science research.

Recently, computational social science has set out to advance social research by using the ever-growing computer processing power, methodological innovations, and the emergence of vast quantities of data in the digital age to achieve better knowledge about social phenomena. The central thesis of this book is that such computational approaches have enormous potential to advance conflict research. Our goal in this introductory chapter—and the book as a whole—is (a) to demonstrate how such computational approaches can be used to improve our understanding of conflict at any scale and (b) to call for the consolidation of computational conflict research as a field of research that collectively aims to gather such insights.

We argue that computational conflict research, i.e., the use of computational approaches to study conflict, can advance conflict research through at least three major innovative pathways:

-

1.

The identification of spatio-temporal dynamics and mechanisms behind conflicts through simulation models that allow to track the interaction of actors in conflict scenarios and to understand the emergence of aggregated, macro-level consequences.

-

2.

The availability of new, fine-grained datasets of conflict events at all scales from the local to the global (“big data”) that have become available through digitization together with novel techniques in the computer age to collect, store, and analyze such data.

-

3.

The combination of these simulation and other advanced computational methods with this vast, fine-grained empirical data.

To demonstrate the potential of these innovations for conflict research, this book brings together a set of (a) chapters that discuss these advances in data availability and guide through some of these computational methods and (b) original studies that showcase how various cutting-edge computational approaches can lead to new insights on conflict at various geographic scales and degrees of violence. Following Hillmann (2007, p. 432), conflict is understood in this book as opposition, tensions, clashes, enmities, struggles, or fights of various intensities between social units. This definition is deliberately broad: Social units can range from small groups of individuals without formal organization to institutions with differentiated organizational structure to large and complex units such as entire nation-states or even batches of countries. Examples in this book will include street protesters, terrorist organizations, rebel groups, political parties, and sets of parliaments. Conflict, as understood here, can be non-violent or violent.Footnote 2 Some studies in this book will deal with the former, covering social, non-violent conflicts such as clashes between political parties in parliamentary debates or normative shifts in social networks, while others will deal with the latter, including the spatial structure of civil war violence or the extortion mechanisms rebel groups use to exploit enterprises.Footnote 3

This chapter is structured as follows: We first give a short summary of the rise of computational social science for readers who are unfamiliar with this trend (Sect. 2). Next, we discuss how computational approaches have already enriched conflict research (Sect. 3). Finally, we give an overview of the contributions of this volume, laying out how they move the field forward. We also offer a visualization that allows to map the field of computational conflict research in a two-dimensional space (Sect. 4).

2 The Rise of Computational Social Science

The modern field of computational social science has emerged at the end of the first decade of our century starting with a “Perspective” article in Science (Lazer et al., 2009) mainly from scientists in North America, followed by a “Manifesto” (Conte et al., 2012) from scientists in Europe, leading to a great many books, conferences, summer schools, institutes, and novel job postings and titles all over the world in recent years.

The main driver of the popularity of computational social science in the past 10 years was clearly the new availability of large-scale digital data that humans now create by spending time online and by carrying mobile devices. This data accumulates in companies, government agencies, and on the devices of users. Just as a matter of business, engineers from the tech, internet, and information industries enabled, created, and processed increasing amounts of social and cultural data, and, as a consequence, they interfered more and more with large-scale societal processes themselves. Business development in this situation requires not only technical skills but also skills in the interpretation of social data, leading to the emergence of the jobs as data scientists or social data scientists that have combined knowledge in statistics, computer science, and—in particular—social sciences.

While the “social data scientist” is to a large extent an invention of the business world, the term “computational social science” comes from academia—somewhat surprisingly, however, not so much from within the social sciences themselves. Many authors of the two seminal papers (Lazer et al., 2009; Conte et al., 2012) did not obtain their undergraduate training in a social science. They often conducted research in fields such as complex systems, sociophysics, network science, simulation, and agent-based modeling before the term computational social science appeared. Research on complex systems and related fields typically aims at a fundamental understanding of dynamical processes with many independent actors (Simon, 1962). The mode of computation is usually computer simulation (Gilbert and Troitzsch, 2005) and the relation to data is often focused on the explanation of large-scale empirical regularities: the stylized facts, with fat-tailed distributions as the seminal example (Price, 1976; Gabaix et al., 2003).

Due to the focus on universal mechanisms and the interdisciplinarity of contributors also from outside of the traditional social sciences, computational social science represents an integrated approach to the social sciences, where the traditional social and behavioral sciences serve as different perspectives for modeling how people think (psychology), handle wealth (economics), relate to each other (sociology), govern themselves (political science), and create culture (anthropology) (Conte et al., 2012), or operate in geographical space (Torrens, 2010) to gain quantitative and qualitative insight about societal questions and real-world problems (cf. Watts, 2013; Keuschnigg et al., 2017). These aspects can be subsumed under the current, broad definition by Amaral (2017, p. 1) that understands computational social science as an “interdisciplinary and emerging scientific field [that] uses computationally methods to analyze and model social phenomena, social structures, and collective behavior.” Following this definition, computational refers to at least three very different aspects of computing: the retrieval, storage, and processing of massive amounts of digital behavioral data; the development of algorithms for inference, prediction, and automated decision-making based on that data; and the implementation of dynamic computer models for the simulation of social processes.

Many other disciplines have had a “computational” branch for a much longer time than the social sciences. There is computational physics, computational biology, and computational economics to name a few. Also, computational sociology has been formulated already in the time before the omnipresence of the internet and large-scale digital behavioral data, acknowledging that any modern science builds not only on a theoretical and an empirical, but also on a computational component (Hummon and Fararo, 1995).

Today, computational social science is sometimes reduced to being a new science that provides methods for retrieving digital behavioral data for the analysis of people’s social behavior online. Our perspective on the field is broader, including the older simulation-based focus on fundamental mechanisms (e.g., Epstein and Axtell, 1996; Axelrod, 1997). We see computational social science as contributing to a basic scientific understanding of social processes, to the development of new methods, to societal insights informing current political debates and international relations. In the following section, we discuss how computational social science, understood in this broad sense, has already impacted on the field of conflict research.

3 Computational Approaches to Conflict Research

The use of computational approaches in conflict research is not a new endeavor. A broad range of methods, techniques, and systems have been developed in various scientific fields, including the areas of machine learning, social network analysis, geographic information systems, and computational simulation. In the following, we give a short overview of these strands of research. This review should be understood more as a starting point rather than an end point in mapping the field. Hence, we do not claim completeness and interested readers are invited to explore the works cited in the other chapters of this book, which may serve as useful additional reference points.

Machine learning methods define algorithms, or a set of step-by-step computational procedures, with the aim to find an appropriate model that describes non-trivial regularities in data. In conflict research, these methods have been initially adopted to develop predictive models of conflict outcomes (Schrodt, 1984, 1987, 1990, 1991) and conflict mediation attempts (Trappl, 1992; Fürnkranz et al., 1994; Trappl et al., 1996, 1997).Footnote 4 With the growing availability of detailed empirical data in the last decades, however, the focus has shifted from predicting outcomes in ongoing conflicts to derive early warning indicators of conflicts in the hope for preventing them (Schrodt, 1997; Beck et al., 2000; Schrodt and Gerner, 2000; Trappl et al., 2006; Subramanian and Stoll, 2006; Zammit-Mangion et al., 2012; Perry, 2013; Helbing et al., 2015). Despite the latest major efforts on developing systems of early warning (Trappl, 2006; O’Brien, 2010; Guo et al., 2018), no system has established itself as a reliable tool for policy-making yet (Cederman and Weidmann, 2017). Cederman and Weidmann (2017) identify several pitfalls and provide a number of recommendations on how existing work on data-driven conflict research can be improved.

Most of these machine learning methods cannot only be applied to numeric data, but also to symbolic data (i.e., text, images, and video). These methods are subsumed under the label of computer-aided content analysis (Weber, 1984). Conflict research benefits from these methods by identifying the relation between particular actors and indicators of violence in textual data, thus supporting the analysis of, e.g., online hate speech campaigns, cyber mobbing, and social media flame wars. Examples include analyses of collective sense-making after terrorist attacks based on Twitter comments (Fischer-Preßler et al., 2019) and verbal discrimination against African Americans in the media based on online newspaper articles (Leschke and Schwemmer, 2019). Further details and a survey on the use of these methods in conflict research are available in the chapter “Text as Data for Conflict Research” of this book.

Despite the fact that conflicts are strongly influenced by network dynamics, machine learning methods rarely integrate these dynamics to study interaction between more than two groups. Social network analysis complements these methods and sheds light on the structural and dynamic interaction aspects of the multiple groups involved in conflicts (Wolfe, 2004). Social network analysis has been recognized to be useful for mapping groups’ structure, to identify the division of power within these groups, and to uncover their internal dynamics, patterns of socialization, and the nature of their decision-making processes (Kramer, 2017). Hammarstr and Heldt (2002) successfully applied network analysis methods to study the diffusion of interstate military conflict, while Takács (2002) investigated the influences of segregation on the likelihood of intergroup conflicts when individuals or groups compete for scarce resources. More specifically, the descriptive and explanatory potential of social network analysis has been demonstrated appropriate to study terrorism activities and organizations (Perliger and Pedahzur, 2011; Deutschmann, 2016), to understand the influence of social network structure on the flexibility of a rebel group in peace negotiations (Lilja, 2012), and to assess the influence of antigovernment network structures (i.e., alliances and strategic interactions) in generating conflictual behavior (Metternich et al., 2013).

Analogous to social network analysis that enhances conflict studies by integrating network dynamics, geographic information systems (GIS) offer techniques for refining these studies through the incorporation of spatial data into the analysis (Branch, 2016). Although spatial relationships have often been analyzed in a general way in qualitative conflict research, the recent advances in computing power and the increasing availability of disaggregated and high-resolution spatial data have enabled more sophisticated and quantitative studies (Stephenne et al., 2009; Gleditsch and Weidmann, 2012). Despite these advances, introducing the spatial dimension to conflict research still poses several challenges: Practical, because of the lack of high quality open-source GIS software tools and the lack of educational training in spatial methods and programming; Theoretical, related to different aspects of the definition of “space,” such as choosing spatial units and the appropriate resolution for analysis, as well as the right measure of distance; and Statistical, because of the dependent nature of spatial units of analysis and their interaction with time (Stephenne et al., 2009; Gleditsch and Weidmann, 2012).

While the previously discussed data-driven approaches are primarily focused on uncovering correlations in empirical data, computational simulation-based approaches create a bridge between theory and data that can be used to demonstrate causality. Computational conflict simulation models first appeared during the Cold War (Cioffi-Revilla and Rouleau, 2010). These models used systems of ordinary differential equation or difference equations (ODE) and were implemented using the system dynamics approach (Forrester, 1968). Bremer and Mihalka (1977), following a complex systems approach, developed a discrete model composed of states arrayed geographically and with imperfect perception, provided each with a quantity of “power,” endowed each with action rules based on realistic principles, and set them off to interact with one another in iterative cycles of conflict and cooperation. This model aimed to investigate the likelihood that a power equilibrium can be achieved under particular conditions (Duffy and Tucker, 1995). Cusack and Stool (1990) extended the Bremer and Mihalka model incorporating more realistic rules in which states play multiple roles and they assessed the effects that different sets of rules have on the survival and endurance of states and state systems (Duffy and Tucker, 1995). In line with the complex systems approach, Axelrod (1995) proposed a model to understand the future of global politics through extortion and cooperation among states.

Although different approaches have been used to model and investigate conflicts over the decades, system dynamics was the dominant one until the introduction of the agent-based modeling (ABM) approach (Burton et al., 2017). Cederman (2002) presented a series of agent-based models that trace complex macrohistorical transformations of actors. He argued that in addition to the advantages usually attributed to ABM (i.e., bounded rationality and heterogeneity of entities), this technique also promises to overcome the reification of actors by allowing to superimpose higher-level structures on a lower-level grid of primitive actors. The groundwork of the use of ABM in conflict research was laid by Epstein (2002), who analyzed the conditions under which individuals may mobilize and protest. He examined the complex dynamics of decentralized rebellion and interethnic civil violence and factors such as the legitimacy of a political system, risk-aversion of potential protesters, police strength, and geographic reach. Epstein’s model of civil conflict has subsequently been extended (Ilachinski, 2004; Goh et al., 2006; Lemos et al., 2016; Fonoberova et al., 2018). Bhavnani et al. (2008) created an agent-based computational framework that incorporates factors such as ethnicity, polarization, dominance, and resource type, allowing the study of the relationship between natural resources, ethnicity, and civil war. Similarly, Cioffi-Revilla and Rouleau (2010) developed a model that considers how freedom of social interaction within a state may lead to rebellion and possibly regime change.

Despite the long-standing use of data-driven and simulation-based computational approaches to conflict research, the field of computational conflict research is not clearly defined yet. The efforts are spread over several scientific fields that in their majority do not have the conflict domain as their main target, but rather use it as an application domain in which their methods can be applied. Hence, our book aims at contributing to advancing the field of computational conflict research through a more complete and systematic analysis of what can be done with computational approaches in studying conflict. In the following section, we describe more concretely how the contributions of this book help achieve this goal.

4 The Contributions of This Book

This book covers computational conflict research in a range of facets, with its contributions using a variety of different approaches on several dimensions (methodology, conflict scale, geographic focus, etc.). It thereby addresses the full scope of the field, including primarily data-driven as well as primarily simulation-based approaches. The book brings together contributions from leading and emerging scholars with a diversity of disciplinary backgrounds from physics, mathematics, and biology to computer and data science to sociology and political science. The volume is also a truly international endeavor, with its authors’ institutional affiliations reaching across thirteen countries on three continents.

Methodologically, the book covers a variety of computational approaches from text mining and machine learning to agent-based modeling and simulation to social network analysis. Table 1 gives a more fine-grained overview of the different methodologies and computational approaches used.

Regarding data, several chapters make use of empirical conflict data that has only recently become available in such detail, be it large corpora of text or fine-grained, geo-tagged information on conflict events coded globally from news reports.Footnote 5 Geographically, these case studies add up to a comprehensive set of analyses of recent conflicts that spans multiple continents, as the map in Fig. 1 reveals. These contentions range from conflict lines in parliamentary debates on migration policy in the USA and Canada from 1994 to 2016 (chapter “Migration Policy Framing”) and the representation of street protest in Germany (2014–15) and Iran (2017–18) on social media (chapter “Fate of Social Protests”) to terrorist attacks in Colombia, Afghanistan, and Iraq between 2001 and 2005 (chapter “Non-state Armed Groups”) and violence against civilians in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1998–2000 (chapter “Violence Against Civilians”) to conflict diffusion in South Sudan between 2014 and 2018 (chapter “Conflict Diffusion over Continuous Space”) and rebel group behavior in Somalia from 1991 to the present day (chapter “Rebel Group Protection Rackets”). Hence, a broad range of recent conflicts is covered.

The book is structured in three parts. Part I focuses on data and methods in computational conflict research and contains three contributions. Part II deals with non-violent, social conflict and comprises three chapters. Part III is about computational approaches to violent conflict and covers four chapters. In the following, we give a short overview about these individual chapters.

In the chapter “Advances in Data on Conflict,” Kristian Gleditsch, building on more than two decades of experience in peace and conflict studies, takes a look at the role of data in driving innovation in the field. He argues that the growth of systematic empirical data has been a central innovative force that has brought the field forward. Drawing on several examples, he demonstrates how data has served as a source of theoretical innovation in the field. This progress in data availability, he argues, has helped generate new research agendas. His contribution ends with an inventory of the most valuable data sources on conflict events to date—which, we believe, may be highly useful for readers interested in conducting their own research on conflicts globally.

In the chapter “Text as Data for Conflict Research,” Seraphine F. Maerz and Cornelius Puschmann give insights into how text can be used as data for conflict research. Arguing that computer-aided text analysis offers exciting new possibilities for conflict research, they delve into computational procedures that allow to analyze large quantities of text, from supervised and unsupervised machine learning to more traditional forms of content analysis, such as dictionaries. To illustrate these approaches, they draw on a range of example studies that investigate conflict based on text material across different formats and genres. This includes both conflict verbalized in news media, political speeches, and other public documents and conflict that occurs directly within online spaces like social media platforms and internet forums. Finally, they highlight cross-validation as a crucial step in using text as data for conflict research.

In the chapter “Relational Event Models,” Laurence Brandenberger introduces relational event models (REMs) as a powerful tool to examine how conflicts arise through human interaction and how they evolve over time. Building on event history analysis, these models combine network dependencies with temporal dynamics and allow for the analysis of social influencing and group formation patterns. The added information on the timing of social interactions and the broader network in which actors are embedded can uncover meaningful social mechanisms, Brandenberger argues. To illustrate the added value of REMs, the chapter showcases two empirical studies. The first one shows that countries engaging in military actions in the Gulf region do so by balancing their relations, i.e., by supporting allies of their allies and opposing enemies of their allies. The second one shows that party family homophily guides parliamentary veto decisions and provides empirical evidence of social influencing dynamics among European parliaments. Brandenberger also references her R package, which allows interested conflict researchers to apply REMs.

The chapter “Migration Policy Framing” opens Part II of the book with research on non-violent, social conflicts. Sanja Hajdinjak, Marcella H. Morris, and Tyler Amos put the text-as-data approach that was laid out in the chapter “Text as Data for Conflict Research” into empirical practice. Drawing on more than a decade of parliamentary speeches from the USA and Canada, they analyze how parties frame migration topics in political discourse. Building on work that argues that migration falls in a gap between established societal cleavages over which parties do not have robust, issue-specific ownership, Hajdinjak et al. argue that parties engage in debates on migration topics by diverting attention to areas in which they have established issue ownership. Using structural topic models, they test this assertion by measuring the differences in salience and framing of migration-related topics over time in the debates of the lower houses of Canada and the USA. Doing so, they do indeed find that, in both countries, liberals frame migration differently than conservatives.

In the chapter “Norm Conflict in Social Networks,” an interdisciplinary team of psychologists, sociologists, and physicists—Julian Kohne, Natalie Gallagher, Zeynep Melis Kirgil, Rocco Paolillo, Lars Padmos, and Fariba Karimi—model the spread and clash of norms in social networks. They argue that arriving at an overarching normative consensus in groups with different social norms can lead to intra- and intergroup conflict. Kohne et al. develop an agent-based model that allows to simulate the convergence of norms in social networks with two different groups in different network structures. Their model can adjust group sizes, levels of homophily as well as initial distribution of norms within the groups. Agents in the model update their norms according to the classic Granovetter threshold model, where a norm changes when the proportion of the agents’ ego-network displaying a different norm exceeds the agents’ threshold. Conflict, in line with Heider’s balance theory, is operationalized by the proportion of edges between agents that hold a different norm in converged networks. Their results suggest that norm change is most likely when norms are strongly correlated with group membership. Heterophilic network structures, with small to middling minority groups, exert the most pressure on groups to conform to one another. While the results of these simulations demonstrate that the level of homophily determines the potential conflict between groups and within groups, this contribution also showcases the impressive possibilities of ever-increasing computing power and how they can be used for conflict research: Kohne et al. ran their agent-based simulation on a high performance computing cluster; their simulation took about 315 hours to complete and generated 40 Gigabytes of output data.

Gravovetter’s threshold model and the spread of information in networks also play a role in the chapter “Fate of Social Protests,” in which Ahmadreza Asgharpourmasouleh, Masoud Fattahzadeh, Daniel Mayerhoffer, and Jan Lorenz simulate conditions for the emergence of social protests in an agent-based model. They draw on two recent historical protests from Iran and Germany to inform the modeling process. In their agent-based model, people, who are interconnected in networks, interact and exchange their concerns on a finite number of topics. They may start to protest either because their concern or the fraction of protesters in their social contacts exceeds their protest threshold, as in Granovetter’s threshold model. In contrast to many other models of social protests, their model also studies the coevolution of topics of concern in the public that is not (yet) protesting. Given that often a small number of citizens starts a protest, its fate depends not only on the dynamics of social activation but also on the buildup of concern with respect to competing topics. Asgharpourmasouleh et al. argue that today, this buildup often occurs in a decentralized way through social media. Their agent-based simulation allows to reproduce the structural features of the evolution of the two empirical cases of social protests in Iran and Germany.

In the chapter “Non-state Armed Groups,” an interdisciplinary team with backgrounds in data science, philosophy, biology, and political science—Simone Cremaschi, Baris Kirdemir, Juan Masullo, Adam R. Pah, Nicolas Payette, and Rithvik Yarlagadda—look at the network structure of non-state armed groups (NSAGs) in Colombia, Iraq, and Afghanistan from 2001 to 2005. They use a self-exciting temporal model to ask if the behavior of one NSAG affects the behavior of other groups operating in the same country and if the actions of groups with actual ties (i.e., groups with some recognized relationship) have a larger effect than those with environmental ties (i.e., groups simply operating in the same country). The team finds mixed results for the notion that the actions of one NSAG influence the actions of others operating in the same conflict. In Iraq and Afghanistan, they find evidence that NSAG actions do influence the timing of attacks by other NSAGs; however, there is no discernible link between NSAG actions and the timing of attacks in Colombia. However, they do consistently find that there is no significant difference between the effects that actual or environmental ties could have in these three cases.

In the chapter “Violence Against Civilians,” political scientists Andrea Salvi, Mark Williamson, and Jessica Draper examine why some conflict zones exhibit more violence against civilians than others. They assess that past research has emphasized ethnic fractionalization, territorial control, and strategic incentives, but overlooked the consequences of armed conflict itself. This oversight, Salvi et al. argue, is partly due to the methodological hurdles of finding an appropriate counterfactual for observed battle events. In their contribution, they aim to test empirically the effect of instances of armed clashes between rebels and the government in civil wars on violence against civilians. Battles between belligerents may create conditions that lead to surges in civilian killings as combatants seek to consolidate civilian control or inflict punishment against populations residing near areas of contestation. Since there is no relevant counterfactual for these battles, they utilize road networks to help build a synthetic risk-set of plausible locations for conflict. Road networks are crucial for the logistical operations of a civil war and are thus the main conduit for conflict diffusion. As such, the majority of battles should take place in the proximity of road networks; by simulating events in the same geographic area, Salvi et al. are able to better approximate locations where battles hypothetically could have occurred, but did not. They test this simulation approach using a case study of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (1998–2000) and model the causal effect of battles using a spatially disaggregated framework. Their work contributes to the literature on civil war violence by offering a framework for crafting synthetic counterfactuals with event data, and by proposing an empirical test for explaining the variation of violence against civilians as a result of battle events.

In the chapter “Conflict diffusion over Continuous Space,” statistician Claire Kelling and political scientist YiJyun Lin study the diffusion of conflict events through an innovative application of methods of spatial statistics. They investigate how spatial interdependencies between conflict events vary depending on several attributes of the events and actors involved. Kelling and Lin build on the fact—similarly observed by Gleditsch in the chapter “Advances in Data on Conflict”—that due to recent technological advances, conflict events can now be analyzed using data measured at the event level, rather than relying on aggregated units. Looking at the case of South Sudan, they demonstrate how the intensity function defined by the log-Gaussian Cox process model can be used to explore the complex underlying diffusion mechanism under various characteristics of conflict events. Their findings add to the explanation of the process of conflict diffusion, e.g., by revealing that battles with territorial gains for one side tend to diffuse over larger distances than battles with no territorial change, and that conflicts with longer duration exhibit stronger spatial dependence.

In the chapter “Rebel Group Protection Rackets,” Frances Duffy, Kamil C. Klosek, Luis G. Nardin, and Gerd Wagner present an agent-based model that simulates how rebel groups compete for territory and how they extort local enterprises to finance their endeavors. In this model, rebel groups engage in a series of economic transactions with the local population during a civil war. These interactions resemble those of a protection racket, in which aspiring governing groups extort the local economic actors to fund their fighting activities and control the territory. Seeking security in this unstable political environment, these economic actors may decide to flee or to pay the rebels in order to ensure their own protection, impacting the outcomes of the civil war. The model reveals mechanisms that are helpful for understanding violence outcomes in civil wars, and the conditions that may lead certain rebel groups to prevail. By simulating several different scenarios, Duffy et al. demonstrate the impact that different security factors have on civil war dynamics. Using Somalia as a case study, they also assess the importance of rebel groups’ economic bases of support in a real-world setting.

The agent-based simulation models constructed in several of these chapters are all available online. They can be downloaded or applied directly in the web browser. Interested readers can thus replicate the outcomes presented in this book, adjust parameters, and build on the code to advance in their own research. An overview of this online material is available at the end of this book, together with information on further supplementary material, such as replication files and links to the data sources used.

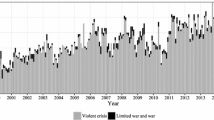

Figure 2 shows how the chapters that are based on empirical studies (i.e., Parts II and III of the book) can be placed on a two-dimensional space that can be interpreted as representing the field of computational conflict research. In this space, the vertical axis describes the intensity of the conflict studied, running from “non-violent” to “violent.” The horizontal axis describes the computational approach that is used, ranging from “simulation-based” to “data-driven.” As can be seen, the book at hand covers all four quadrants that constitute the field. The chapter “Norm Conflict in Social Networks,” for example, where the interaction of actors with different social norms is studied, is an example of computational conflict research that is based entirely on simulations and that deals with non-violent, social conflict. The chapter “Migration Policy Framing,” in which party differences in parliamentary debates are analyzed, also deals with non-violent conflict, but is mostly data-driven. In the upper left quadrant, we see the chapter “Rebel Group Protection Rackets,” which, with its agent-based model on rebel group protection rackets, deals with violent conflict and is mainly simulation-based, although some parameters are adjusted according to the real-world case of Somalia as mentioned above (accordingly, it is placed somewhat towards the center of the horizontal axis, denoting a mix of both simulation-based and data-driven approaches). Finally, in the upper right corner, we see, for instance, the chapter “Conflict Diffusion over Continuous Space,” which deals with the diffusion of violent conflict events (e.g., battles) in continuous space and is mainly data-driven. The chapter “Non-state Armed Groups” uses both a large-scale dataset and draws on simulation techniques and is thus placed toward the center of the horizontal axis.

Although this two-dimensional representation is of course quite simple—and perhaps even simplistic—it should in theory be possible to place any research conducted in the field of computational conflict research—including the studies discussed in Sect. 3—somewhere in this space. We thus hope this representation may prove to become a useful heuristic for the field.

By bringing together novel research by an international team of scholars from a range of fields, this book strives to contribute to consolidating the emerging field of computational conflict research. It aims to be a valuable resource for students, scholars, and a general audience interested in the prospects of using computational social science to advance our understanding of conflict dynamics in all their facets.

Notes

- 1.

Luce and Raiffa (1989, p. 1) actually talk specifically about “conflict of interest” and mention “inner struggle” as a third topic that has received “comparable attention” apart from “God” and “love.” Rapoport may have misremembered the exact quote or he deliberately subsumed “conflict of interest” and “inner struggle” under “conflict.”

- 2.

Gleditsch, in the chapter “Advances in Data on Conflict” of this book, will identify too narrow definitions of conflict that focus on violent conflict alone as one major obstacle that prevents progress in the field. He gives the example of recent street protests in Venezuela and argues that it would be “absurd” not to treat this as a conflict due to the absence of organized armed violence in the sense of a civil war. By taking a broad perspective and combining research on non-violent and violent conflict, this book aims to contribute to overcoming this issue.

- 3.

When we use the term “violence” to classify the research conducted in this book, we use it to denote physical violence. Some definitions of violence, e.g., by the World Health Organization, also treat psychological and emotional violence as sub-types of violence (Krug et al., 2002). Sometimes verbal violence is described as another type of violence (Nieto et al., 2018). In that sense, words—and thus, for instance, also the analyses of parliamentary speeches analyzed in Part II of the book, which we titled “Computational Research on Non-Violent conflict” could also be seen as potentially dealing with violence, if such a broader definition of violence were used. Yet we deem the distinction between conflict based on physical force (=violence) and that carried out without the use of physical force (=non-violently) meaningful and thus decided to stick to it. In principle, computational conflict research could of course cover any kind of violence.

- 4.

A more detailed overview of the initial uses of these methods in conflict research can be found in Trappl and Miksch (1991).

- 5.

For an overview of recent developments in data on conflict see the contribution by Gleditsch in the chapter “Advances in Data on Conflict” of this volume.

References

Amaral, I. (2017). Computational social sciences (pp. 1–3). Cham: Springer.

Axelrod, R. (1995). Building new political actors: A model for the emergence of new political actors. In N. Gilbert, R. Conte (Eds.) Artificial societies: The computer simulation of social life. London: University College Press.

Axelrod, R. (1997). The complexity of cooperation: Agent-based models of competition and collaboration (Vol. 3). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Beck, N., King, G., & Zeng, L. (2000). Improving quantitative studies of international conflict: A conjecture. American Political Science Review, 94(1), 21–35.

Bhavnani, R., Miodownik, D., & Nart, J. (2008). REsCape: An agent-based framework for modeling resources, ethnicity, and conflict. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 11(2), 7.

Branch, J. (2016). Geographic information systems (GIS) in international relations. International Organization, 70(4), 845–869.

Bremer, S. A., & Mihalka, M. (1977). Machiavelli in machina: Or politics among hexagons. In K. W. Deutsch, B. Fritsch, H. Jaquaribe, & A. S. Markovits (Eds.), Problems of the world modeling: Political and social implications (pp. 303–337). Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing.

Burton, L., Johnson, S. D., & Braithwaite, A. (2017). Potential uses of numerical simulation for the modelling of civil conflict. Peace Economics, Peace Science, and Public Policy, 23(1), 1–39.

Cederman, L.-E. (2002). Endogenizing geopolitical boundaries with agent-based modeling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(Supplement 3), 7296–7303.

Cederman, L.-E., & Weidmann, N. B. (2017). Predicting armed conflict: Time to adjust our expectations? Science, 355(6324), 474–476.

Cioffi-Revilla, C., & Rouleau, M. (2010). MASON RebeLand: An agent-based model of politics, environment, and insurgency. International Studies Review, 12(1), 31–52.

Conte, R., Gilbert, N., Bonelli, G., Cioffi-Revilla, C., Deffuant, G., Kertesz, J., et al. (2012). Manifesto of computational social science. The European Physical Journal Special Topics, 214(1), 325–346.

Cusack, T. R., & Stool, R. J. (1990). Exploring realpolitik: Probing international relations theory with computer simulation. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Dahrendorf, R. (1959). Class and class conflict in industrial society. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Deutschmann, E. (2016). Between collaboration and disobedience: The behavior of the Guantánamo detainees and its consequences. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 60(3), 555–582.

Duffy, G., & Tucker, S. A. (1995). Political science: Artificial intelligence applications. Social Science Computer Review, 13(1), 1–20.

Epstein, J. M. (2002). Modeling civil violence: An agent-based computational approach. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(Supplement 3), 7243–7250.

Epstein, J. M., & Axtell, R. (1996). Growing artificial societies: Social science from the bottom up. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Fischer-Preßler, D., Schwemmer, C., & Fischbach, K. (2019). Collective sense-making in times of crisis: Connecting terror management theory with twitter reactions to the berlin terrorist attack. Computers in Human Behavior, 100, 138–151.

Fonoberova, M., Mezić, I., Mezić, J., & Mohr, R. (2018). An agent-based model of urban insurgence: Effect of gathering sites and Koopman mode analysis. PLos One, 13(10), 1–25.

Forrester, J. W. (1968). Principle of systems. Lawrence: Wright-Allen Press.

Fürnkranz, J., Petrak, J., Trappl, R., & Bercovitch, J. (1994). Machine learning methods for international conflict databases: A case study in predicting mediation outcome. Technical Report TR-94–33. Viena: Austrian Research Institute for Artificial Intelligence.

Gabaix, X., Gopikrishnan, P., Plerou, V., & Stanley, H. E. (2003). A theory of power-law distributions in financial market fluctuations. Nature, 423(6937), 267–270.

Gilbert, N., & Troitzsch, K. (2005). Simulation for the Social Scientist. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Gleditsch, K. S., & Weidmann, N. B. (2012). Richardson in the information age: Geographic information systems and spatial data in international studies. Annual Review of Political Science, 15, 461–481.

Goh, C. K., Quek, H. Y., Tan, K. C., & Abbass, H. A. (2006). Modeling civil violence: An evolutionary multi-agent, game theoretic approach. In 2006 IEEE international conference on evolutionary computation (pp. 1624–1631). Piscataway, NJ: IEEE.

Graham, D. W. (2019). Heraclitus (fl. c. 500 B.C.E.). https://www.iep.utm.edu/heraclit/. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

Guo, W., Gleditsch, K., & Wilson, A. (2018). Retool AI to forecast and limit wars. Nature, 562, 331–333.

Hammarstr, M., & Heldt, B. (2002). The diffusion of military intervention: Testing a network position approach. International Interactions, 28(4), 355–377.

Helbing, D., Brockmann, D., Chadefaux, T., Donnay, K., Blanke, U., Woolley-Meza, O., et al. (2015). Saving human lives: What complexity science and information systems can contribute. Journal of Statistical Physics, 158(3), 735–781.

Hillmann, K.-H. (2007). Wörterbuch der Soziologie. Stuttgart: Kröner.

Hummon, N. P., & Fararo, T. J. (1995). The emergence of computational sociology. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 20(2–3), 79–87.

Ilachinski, A. (2004). Artificial war: Multiagent-based simulation of combat. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company.

Keuschnigg, M., Lovsjö, N., & Hedström, P. (2017). Analytical sociology and computational social science. Journal of Computational Social Science, 1, 3–14.

Kramer, C. R. (2017). Network theory and violent conflicts. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Krug, E. G., Dahlberg, L. L., Mercy, J. A., Zwi, A. B., & Lozano, R. (2002). World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Lazer, D., Pentland, A., Adamic, L., Aral, S., Barabási, A.-L., Brewer, D., et al. (2009). Computational social science. Science, 323(5915), 721–723.

Lemos, C., Lopes, R. J., & Coelho, H. (2016). On legitimacy feedback mechanisms in agent-based modeling of civil violence. International Journal of Intelligent Systems, 31(2), 106–127.

Leschke, J. C., & Schwemmer, C. (2019). Media bias towards African-Americans before and after the Charlottesville rally. In Weizenbaum conference (p. 10). DEU.

Lilja, J. (2012). Trust and treason: Social network structure as a source of flexibility in peace negotiations. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 5(1), 96–125.

Luce, R. D., & Raiffa, H. (1989). Games and decisions: Introduction and critical survey. North Chelmsford, MA: Courier Corporation.

Marx, K., & Engels, F. ([1848]2002). The communist manifesto. London: Penguin Books.

Metternich, N. W., Dorff, C., Gallop, M., Weschle, S., & Ward, M. D. (2013). Antigovernment networks in civil conflicts: How network structures affect conflictual behavior. American Journal of Political Science, 57(4), 892–911.

Nieto, B., Portela, I., López, E., & Domínguez, V. (2018). Verbal violence in students of compulsory secondary education. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 8(1), 5–14.

O’Brien, S. P. (2010). Crisis early warning and decision support: Contemporary approaches and thoughts on future research. International Studies Review, 12(1), 87–104.

Perliger, A., & Pedahzur, A. (2011). Social network analysis in the study of terrorism and political violence. PS: Political Science and Politics, 44(1), 45–50.

Perry, C. (2013). Machine learning and conflict prediction: A use case. Stability: International Journal of Security & Development, 2(3), 1–18.

Price, D. D. S. (1976). A general theory of bibliometric and other cumulative advantage processes. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 27(5), 292–306.

Rapoport, A. (1995). The origins of violence: Approaches to the study of conflict. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Ritzer, G., & Stepnisky, J. (2017). Contemporary sociological theory and its classical roots: The basics. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Schrodt, P. A. (1984). Artificial intelligence and international crisis: An application of pattern recognition. In Annual meeting of the international studies association, Washington, DC. Connecticut: International Studies Association.

Schrodt, P. A. (1987). Classification of interstate conflict outcomes using a bootstrapped CLS algorithm. In Annual Meeting of the International Studies Association, Washington, DC. Connecticut: International Studies Association.

Schrodt, P. A. (1990). Predicting interstate conflict outcomes using a bootstrapped ID3 algorithm. Political Analysis, 2, 31–56.

Schrodt, P. A. (1991). Prediction of interstate conflict outcomes using a neural network. Social Science Computer Review, 9(3), 359–380.

Schrodt, P. A. (1997). Early warning of conflict in Southern Lebanon using Hidden Markov Models. In Annual meeting of the international studies association, Washington, DC. Connecticut: International Studies Association.

Schrodt, P. A., & Gerner, D. J. (2000). Cluster-based early warning indicators for political change in the contemporary levant. American Political Science Review, 94(4), 803–818.

Simmel, G. (1904). The sociology of conflict. American Journal of Sociology, 9(4), 490–525.

Simon, H. A. (1962). The architecture of complexity. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 106, 467–482.

Stephenne, N., Burnley, C., & Ehrlich, D. (2009). Analyzing spatial drivers in quantitative conflict studies: The potential and challenges of geographic information systems. International Studies Review, 11(3), 503–522.

Subramanian, D., & Stoll, R. J. (2006). Events, patterns, and analysis forecasting international conflict in the twenty-first century. In R. Trappl (ed.) Programming for Peace (Vol. 2, pp. 145–160). Dordrecht: Springer.

Takács, K. (2002). Social network and intergroup conflict. PhD thesis, University of Groningen.

Torrens, P. M. (2010). Geography and computational social science. GeoJournal, 75(2), 133–148.

Trappl, R. (1992). The role of artificial intelligence in the avoidance of war. In R. Trappl (Ed.) Cybernetics and systems research (Vol. 1, pp. 1667–1772). Singapore: World Scientific.

Trappl, R. (Ed.). (2006). Programming for peace. Advances in group decision and negotiation (Vol. 2). Dordrecht: Springer.

Trappl, R., & Miksch, S. (1991). Can artificial intelligence contribute to peacefare? In Proceedings of the artificial intelligence AI’91 (pp. 21–30). Prague: Technical University.

Trappl, R., Fürnkranz, J., & Petrak, J. (1996). Digging for peace: Using machine learning methods for assessing international conflict databases. In W. Wahlster (ed.) Proceedings of the 12th European conference on artificial intelligence (pp. 453–457). Chichester: Wiley.

Trappl, R., Fürnkranz, J., Petrak, J., & Bercovitch, J. (1997). Machine learning and case-based reasoning: Their potential role in preventing the outbreak of wars or in ending them. In G. Della Riccia, H. J. Lenz, & R. Kruse (Eds.) Learning, networks and statistics (Vol. 382, pp. 209–225). Vienna: Springer.

Trappl, R., Hörtnagl, E., Rattenberger, J., Schwank, N., & Bercovitch, J. (2006). Machine learning methods for better understanding, resolving, and preventing international conflicts. In R. Trappl (ed.) Programming for peace (Vol. 2, pp. 251–318). Dordrecht: Springer.

Waltz, K. N. (2001). Man, the state, and war: A theoretical analysis. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Watts, D. J. (2013). Computational social science: Exciting progress and future directions. The Bridge on Frontiers of Engineering, 43(4), 5–10.

Weber, R. P. (1984). Computer-aided content analysis: A short primer. Qualitative Sociology, 7(1–2), 126–147.

Wolfe, A. W. (2004). Network thinking in peace and conflict studies. Peace and Conflict Studies, 11(1), 4.

Zammit-Mangion, A., Dewar, M., Kadirkamanathan, V., & Sanguinetti, G. (2012). Point process modelling of the afghan war diary. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(31), 12414–12419.

Acknowledgements

Most of the contributors of this book met at the BIGSSS Summer School in Computational Social Science: Research Incubators on Data-driven Modeling of Conflicts, which took place from July 23 to August 3, 2018 at Jacobs University in Bremen, Germany. The summer school was organized by Jan Lorenz, Arline Rave, Klaus Boehnke, Adalbert Wilhelm, and Emanuel Deutschmann and was possible through financial support from Volkswagen Foundation, via a grant in their initiative “International Research in Computational Social Sciences” (grant No: 92145). Most of the chapters originate from the research started in the research incubators at the school and we are pleased that the teams continued to work together after leaving Bremen to turn their projects into the chapters that now form this book. We, the editors, would like to thank Arline Rave for her extraordinary dedication in organizing the summer school. James Kitts provided important support and advice; Lisa Gutowski assisted in finalizing the back matter of the book. We are also grateful to Henrik Dobewall and Peter Holtz who gave helpful input and to the editors at Springer Nature for their support in the publishing process. Thanks to Volkswagen Foundation, this book is also available open access and free for anyone to read. Most importantly, we would like to thank the authors for their contributions to this book.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Deutschmann, E., Lorenz, J., Nardin, L.G. (2020). Advancing Conflict Research Through Computational Approaches. In: Deutschmann, E., Lorenz, J., Nardin, L., Natalini, D., Wilhelm, A. (eds) Computational Conflict Research. Computational Social Sciences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29333-8_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29333-8_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-29332-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-29333-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)