Abstract

This chapter focuses on ethical issues in cybersecurity in business. It first sketches the main ethical issues discussed in the academic literature thus far. Next, it identifies some important topics that have not yet received the attention they deserve. The chapter then focuses on one of those topics, ransomware attacks, one of the most prevalent cybersecurity threats to businesses today. It provides a brief overview of the main types of ransomware attacks and discusses businesses’ responsibilities to their stakeholders to respond to them. Daniel Engster’s care-based stakeholder approach is used to assess the responsibilities that businesses have to their stakeholders. The analysis involves establishing who counts as a stakeholder when a ransomware attack occurs and what the stakeholders’ interests might be. Based on stakeholders’ interests, the analysis concludes on whether businesses have an ethical responsibility to their stakeholders to (1) respond to grey hat demands by patching identified vulnerabilities within the given timeframe and (2) respond to black hat demands by paying the ransom.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Due to the uptake of information and communication technology (ICT) in the business sector, the value of information has increased. Information is now considered the new oil and as oil brought both prosperity and problems, so too does information. Prosperity emanates from the fact that businesses can utilise ICT to reduce costs and increase efficiency by providing round-the-clock availability of both information and services to customers. In providing that availability, problems arise. If information is constantly available, this means that it is constantly vulnerable to an attack. This trade-off between providing availability and securing information is something that businesses must grapple with in carrying out their day-to-day activities not only to protect identifiable data, i.e. individual’s names, addresses, account details etc., but also to remain compliant with the General Data Protection Regulation (2018) (GDPR).

The GDPR in 2018 set the bar for businesses that collect, process, analyse and store EU citizen’s identifiable information. It compels businesses who physically reside within the jurisdiction of the GDPR to be compliant, and extends to those that reside outside the EU who process EU citizens’ identifiable information (European Commission 2018a, b; see also Chap. 5). The GDPR is particularly relevant when businesses are hacked, as it compels them to notify the National Data Regulator when a data leak/breach occurs. A failure to report a data leak or breach within 72 h of the breach occurring, can result in a fine up to the value of 4% of the businesses entire annual returns (European Commission 2018a, b). Additionally, if an organisation is non-compliant with the GDPR, —and it is established that non-compliance has caused material damage, such as financial loss, or non-material damage, such as reputational loss or psychological distress to individuals— those individuals can claim compensation (European Commission 2018a, b). Thus, non-compliance can result in significant legal and economic consequences for a business.

From an economic perspective, the cost of data breaches is increasing. For example, the Ponemon Institute’s 2018 study suggests that the average cost of data breaches of 2500–100,000 lost or stolen records is globally US $3.86 million, which is a 6.4% increase on their 2017 report. Wenger et al. (2017) point to the reputational damage that can result from a successful cyber-attack. They state that a significantly large percentage of consumers are less likely to engage with a business that has been hacked, even if they were not directly affected by the attack. In efforts to detect and prevent cybersecurity breaches and data loss, businesses are investing large sums of money into cybersecurity. For example, a study conducted by Bromium states that large enterprise organisations are spending on average US $16.7 million annually on cybersecurity (Bromium 2016).

While individuals, businesses, acadeics and governmental organisations are trying to grapple with the legal and financial side to cybersecurity threats and responses, very few have lended their attention to the ethics of cybersecurity. Ethics and cybersecurity deserve the attention of the reader, the scholarly community and professionals for two fundamental reasons. (1) A cyber-attack is a matter of when, not if. Businesses must therefore adequately prepare themselves for the inevitable by exploring the response options available to them and making an informed decision on the most appropriate, fast and effective response that is in the interests of named stakeholders. (2) Businesses have a responsibility to ensure that the hardware and software that they use to process, store and analyse identifiable information has an adequate level of security to protect the users who have access to those systems. Businesses must also protect the confidentiality and privacy of individuals data held within those systems. For businesses to have any chance of achieving this, they must be aware of the threat landscape. In knowing the main threats, businesses can allocate sufficient resources to protect themselves, it is an efficient use of resources and it has the potential to reduce the likelihood of a successful attack.

This chapter focuses on one main threat, ransomware attacks and is structured in the following way. Firstly, we present a brief overview of the ethical issues that arise in the literature on cybersecurity in business. Next, we observe that there are important gaps in the current debate with regard to (i) education (ii) ransomware attacks and (iii) the disclosure of data breaches. We then introduce Daniel Engster’s care-based stakeholder theory which we think can be used as a normative theory to analyse the under debated issues. Given the space restraints of this chapter, we do not develop a full-fledged stakeholder analysis of all three issues. Instead, we focus in on ransomware attacks, a topic that has prominently featured in the news in the past few years.

2 Ethical Issues in Cybersecurity

In a systematic literature review focused on cybersecurity and ethics, we identified the 15 most frequently discussed ethical issues in cybersecurity in the business domain. Table 6.1 ranks the frequency in which these ethical issues arise (Yaghmaei et al. 2017).

The ethical issues listed are wide ranging and are context relative. For example, privacy arises in terms of data breaches and keeping information secure from unauthorised access. It also surfaces in respect of employee privacy in the workplace. Whereas autonomy, for example, is discussed in terms of data collection, processing, analysis and storage.

In addition to identifying the ethical issues in cybersecurity, we note that (1) the main threats in cybersecurity stem from attackers targeting vulnerabilities in people and technology and (2) the impacts of cybersecurity breaches can be wide ranging, from having a limited impact to having a detrimental effect on the data owner, the business and wider society (Yaghmaei et al. 2017).

3 Gaps in the Literature on Ethics and Cybersecurity

There are at least three important gaps in the ethical literature. They relate to (1) ransomware attacks, (2) education and (3) the disclosure of data breach information. More specifically, there appears to be a lack of thorough ethical analysis on (1) the ethical responsibilities that businesses have to specific stakeholders to engage with grey hats and black hats on the continuum of ransomware attacks, (2) the ethical responsibilities that businesses have to specific stakeholders to improve their employees cybersecurity awareness and expertise despite it being known that one of the main precursors of successful cyber-attacks is the inadvertent actions of employees and (3) the ethical responsibilities that businesses have to specific stakeholders to disclose data breach information.

-

(1)

F-Secure reports that technology and people are the two main weaknesses in cybersecurity in business (F-Secure 2018). Cybercriminals exploit technology through supply chain vulnerabilities or unknown vulnerabilities (otherwise known as zero-day). The European Commission offers a certificate to ethical hackers (European Council 2018a, b). Ethical hackers, otherwise known as white hats, are security testers who try to find vulnerabilities in information systems, networks and IT infrastructures (for more details see Chap. 9). Grey hats are not traditionally known as ethical hackers as they also search for vulnerabilities but do so without the knowledge of the systems owner. Both grey hats and white hats have the intention to find the vulnerabilities before a black hat (a malicious hacker) finds them. Despite grey hats undertaking their endeavours in the absence of consent, they argue that their actions are warranted as they contribute to a safer cyber environment for all by making it more difficult for black hats to successfully attack businesses for financial, political or other malicious purposes (Leiwo and Heikkuri 1998). A discussion in the ethical literature questions whether grey hats actions are ethical (Leiwo and Heikkuri 1998; Brey 2007; McReynolds 2015). It centres on the issue of consent and concludes that grey hat actions are in fact unethical. Another popular topic relating hacking is the hacker ethic. The hacker ethic relies on the notion that all information should be free and unlimited. This is one argument used by hackers to justify exposing questionable activities or corporations or governments. Brey (2007) makes a valid point that if all information was free and unlimited, this would go against the accepted Western interpretation of intellectual property, as it would impede individuals’ ability to profit from patented information. It also would be a huge privacy infringement and, as a consequence, could not be considered ethical.

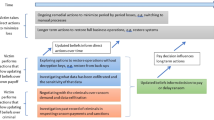

The literature fails to address businesses interactions with hackers, in particular in relation to the continuum of ransomware attacks (Yaghmaei et al. 2017). We take this opportunity to share more insights into how grey hats and black hats do "business". Consider the following. When a grey hat finds a vulnerability, he notifies the owner (in this case let us presume the owner is a business) by giving them a certain amount of time to fix the vulnerability. In failing to fix or “patch” the vulnerability, the grey hat threatens to release the vulnerability to the public. Releasing the vulnerability to the public means that the vulnerability can be accessed by anyone including malicious hackers, making the business more likely to be attacked. Conversely, a black hat might choose to install ransomware on a business’s system that shuts down all business services until the business either (1) identifies and resolves the problem themselves or (2) takes the risk of paying the ransom to the hacker in the hope that the ransomware will be removed upon receipt of payment. As we can see, a ransom of sorts is involved in both activities. Instead of us hashing out whether the act of ransoming a business is unethical, we believe a more fruitful discussion can arise from juxtaposing a grey hat’s ransom against a black hat’s ransom from the viewpoint of specific stakeholders.

-

(2)

People are a weakness in cybersecurity in business due to human error and due to their considerable lack of cybersecurity knowhow (Wenger et al. 2017). This weak spot is something that cybercriminals exploit to target businesses and achieve their ends. Despite businesses and international bodies acknowledging that cybersecurity awareness and education needs to improve (PECB 2017; ENISA 2018; Kaspersky Lab 2018), we note that there is little ethical research that examines the extent to which businesses are responsible for doing so (Yaghmaei et al. 2017). In this instance, we interpret ethical analysis as one that considers specific stakeholders’ interests when it comes to education and assessing how those interests might conflict with one another and how such conflict could be resolved.

-

(3)

End-users have expressed their desire to know if their data has been breached (Wenger et al. 2017). As data breaches have the potential to cause irreparable damage to a business’s reputation and can incur a financial cost, it is in a business’ interests to lessen the impact of a data breach. It is interesting that the ethical literature mentions businesses’ responsibility to disclose data breach information when private or identifiable information has been breached. However, there is no discussion that covers the fact that non-disclosure contributes to the weakening of an already fragile cyber-environment. In addition, little is offered in respect of how underreporting cybersecurity breaches affects the authenticity of cybersecurity incident reports, which can otherwise be used as effective tools that illustrate the cyber threat landscape.

4 Care-Based Stakeholder Theory

To conduct an ethical analysis of the ethical responsibilities that businesses have to specific stakeholders to respond to grey hats and black hats ransoms, we apply a stakeholder approach. Edward Freeman is considered the founding father of stakeholder theory (ST) since the publication of his book Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (1984). Therein, stakeholders are viewed as important but nevertheless a means through which the corporation can achieve its preordained goals (Freeman 1984). In Freeman’s later work, the stakeholder assumes a more central role in the firm such that they have personal projects that the corporation should be constructed to serve (Freeman and Gilbert 1989). An even more recent paper by Freeman and Gilbert (1992) lists the shortcomings of ST, paying particular attention to the language used to describe ST. They argue that the autonomous—masculinist—individualistic mode of thinking surrounding ST reduces its applicability to business today. Two years after this publication, Freeman and Gilbert published a more elaborate paper with Wicks on the specific shortcomings of ST (Wicks et al. 1994). In their paper, they reinterpret the existing version of ST through the lens of care ethics, which they refer to as feminist ethics (Wicks et al. 1994). They note that in order for businesses to flourish in a fast-paced ever-changing business environment, there is a need to replace the masculinist language of conflict with the feminist language of communication, cooperation and collective action. One example they give is to replace notions of competition and control with cooperation and communication. They state that businesses need to share information, embrace change and improve their networks rather than try to exert control over their environment. Wicks et al. (1994) argue that ST theory considers corporations as webs of relations amongst stakeholders whose interests need to be at the core of decision-making processes and, in this way, ST is a way of interpreting the meaning of the corporation and the responsibilities that businesses have to those inside and outside the business. Burton and Dunn (1996) extend the work of Wicks et al. by claiming that care ethics has a natural affinity to ST and that Gilligan’s work on care ethics is a strong lens through which to view the theory.

Burton and Dunn (1996) advocate using Wicks et al.’s (1994) application of care ethics to ST, stating that their reinterpretation offers a more practical approach to it (Burton and Dunn 1996). Daniel Engster (2011) narrows the focus on the practical application of this care-based stakeholder approach and the notion of creating a caring business. He argues that while the idea of using care ethics and ST in business seems logical, flaws still exist. He notes that businesses are left with the following three questions: (1) who exactly counts as a stakeholder? (2) how should businesses distribute care to those stakeholders? and (3) what ethical approaches should businesses adopt when conflict arises amongst stakeholders? For example, is it possible for businesses to follow a particular principle that might mitigate stakeholder conflict? Engster addresses these predicaments by combining insights taken from Freeman (1984), Freeman (2010), Freeman and Gilbert (1989, 1992), Wicks et al. (1994), and Burton and Dunn (1996).

-

(1)

In relation to the first question, Engster argues that stakeholders should include those whose functioning and survival is directly tied to the firm’s activities namely, shareholders, employees, the local community, customers, suppliers and competitors (Engster 2011). This is counter to Freeman’s definition of a stakeholder, which includes all individuals who are affected by the firm. Engster states that it is impossible to include all individuals who are affected by the firm as this would exhaust businesses care, energy and resources and would not enable a business to allocate care to those who need it the most (Engster 2011).

-

(2)

In respect of the second question, Engster offers three ethical principles that can be used as tools in the decision-making process. These principles are (a) the proximity principle, (b) the relational principle (both previously advocated by Burton and Dunn 1996) and (c) the urgency principle.

-

(a)

The proximity principle states that there is justification in using our limited resources to care for individuals who are in some way close to us before attempting to care for distant others. This puts limited resources to the best possible use as we can attend more directly to individuals who are close to us based on the understanding that we usually have a better idea of their circumstances, customs, and needs, and can therefore care better for them than for distant others. It can be argued that the proximity principle justifies: (a) caring for ourselves before others; (b) caring for individuals who are geographically and temporally close to us before those who are far away; and (c) caring for individuals in our own culture or state before those in foreign cultures or states.

-

(b)

The relational principle states that businesses should prioritise caring for individuals with whom we have a close personal relationship over others. Engster (2011) defines a close relationship as one where one party depends on the other for meeting his or her survival and developmental needs, using the analogy of the mother and baby relationship. He states that close relationships deserve priority because they are so closely tied up with the goals of caring. If we apply this interpretation of a close relationship to the business domain, the number of stakeholder relationships that ought to be considered by a business significantly reduces.

-

(c)

Engster (2011) advocates the use of the urgency principle wherein he encourages businesses to care for individuals who have more urgent needs over those with less urgent needs. Using the urgency principle is determined by the effect that an action/inaction could have on a person’s or group’s survival. Engster states that if there is a focus on the urgent needs of stakeholders over less urgent ones, this allows a business to give priority to the needs of individuals or groups who will not survive or function without acting. We note that this principle also reduces the number of stakeholders that must be considered by businesses when making decisions about the distribution of care, time and resources more feasible.

-

(a)

-

(3)

When conflicts arise amongst stakeholders, care ethics dictates that the highest priority be given to shareholders and employees as their interests are “generally more important than those of other stakeholders” (Engster 2007: 107). This does not apply in all cases. For example, he sets one over-riding condition, which is that when the health and safety of employees and customers and other individuals is at stake, the interests of employees and customers should receive the highest priority. He states that prioritising the health and safety interests of employees and customers trumps even the importance of the firm’s survival. Engster (2011) notes that while a strong commitment to worker health and safety and high environmental standards may result in less profit for investors and even the loss of jobs for some workers, individuals are more likely to suffer much greater and immediate threats to their survival and functioning when health, safety and environmental standards are compromised (Engster 2011). He continues his argument by stating that jobs should be favoured by businesses, at least in the short term. There are limits to this policy, as choosing jobs over profit in the long-term may result in the solvency of the firm. He notes that when job cuts are unavoidable, businesses can resort to the ‘rule of consensus’ which requires businesses to try and find solutions to stakeholder conflicts that are acceptable to all by communicating the proposed solutions to stakeholders and trying to solicit alternative proposals from them.

5 Ransomware Attacks

The number of malicious ransomware attacks targeting businesses tripled between 2017 and 2018 (Bromium 2016). Ransomware attacks can be divided into two categories: cryptors and blockers (see also Chap. 2). Cryptors encrypt data on the victim’s device. Usually, the black hat will demand money and in receipt of same will restore the encrypted data. Blockers, otherwise known as lockers, do not interfere with the data stored on the device, instead they prevent the victim from accessing it (Ivanov et al. 2016). Ivanov et al. (2016) report that black hats are using new and more sophisticated ways to target companies that require little effort and have a large pay-off. Our research suggests that ransomware attacks are only considered as such when done through cryptos or blockers by hackers with malicious intent (i.e.) ones who hope to gain financially, politically etc. Grey hats also attack computer network systems and ransom businesses but have different intentions and foresee different outcomes. They scour networks for vulnerabilities and when a vulnerability is found, they notify the owner or business that their system contains vulnerabilities that require fixing. From the grey hat’s perspective, in doing so they are helping improve the overall security of cyberspace. However, it can be argued that the virtuousness of this action is tainted as it involves gaining unauthorised access to a system without the permission of the system owner. It also involves the grey hat ransoming the business into fixing the vulnerability, as the grey hat will traditionally threaten to release the vulnerability if the business does not rectify it within a given timeframe. There is a growing body of evidence that suggests after the public release of vulnerabilities, there is a consequential increase in malicious attacks. The time between the release of a vulnerability and public release of an exploit is referred to as the vulnerability-to-exploit time period and it is decreasing steadily over time. In the past, the time between a vulnerability announcement and the release of a corresponding exploit could be measured in month or years. For example, when Microsoft announced a vulnerability on 17 October 2000, (Microsoft Security Bulletin MS00-078), the exploit followed in the form on Nimda worm on 18 September 2001. This means security teams had 336 days to patch their vulnerability. In the December 2015 Microsoft security bulletin, exploits were available for two of the eight disclosed vulnerabilities on the day that the public announcement was made (CISCO 2018). Although it could be argued that a grey hat threatening to release vulnerability information to the public acts as a catalyst for fixing the vulnerability, this, however, does not remove the threat itself. On the basis that a threat is made at all, one could counter argue that this practice is unethical as the researcher is using the business as a means to an end. Yet, when grey hats ransom businesses, not for money but for the greater good of cyberspace, they create a common ground with black hats. The common ground is ransoming and punishing businesses who do not comply with their demands. We argue that both types of hackers fall on different points on the same ransomware spectrum.

6 The Stakeholders and Their Interests

We use Engster’s method to identify the main stakeholders and their interests in both grey hat and black hat ransom attacks and assess whether a conflict of interest exists amongst stakeholders. In doing so, we aim to establish what exactly are businesses’ responsibilities to their stakeholders in these situations. In addition, we consult the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Code of Ethics & Professional Conduct (‘the Code’) to which all members of the ACM including all computing professionals are bound (ACM 2018a, b). As the ACM’s code extends to security researchers (white hat and grey hat hackers), we include hackers as the seventh stakeholder (see also Chap. 9). We also note that the ACM rank the general public as being the first and foremost stakeholder in cybersecurity. We found this interesting, as Engster (2011) does not include the general public in his care-based stakeholder theory. In this instance, where the actions of hackers can affect the functioning and survival of members of the general public, the criteria that Engster uses to identify who counts as a stakeholder (see above), we believe that it is appropriate to name the general public as the eighth stakeholder.

6.1 Shareholders

Grey hat and black hat ransoms create more issues for shareholders than any other stakeholder. For example, it could be argued that one element of success of a firm depends on IT systems. If those systems are inadequately protected, this affects shareholders’ interests. Shareholders are interested in “a fair return on his or her investment” (Engster 2011: 101). While a grey hat identifying vulnerabilities is not authorised or instigated by the shareholders, the shareholders are now in a position of reduced power as they are now subject to the terms as set by the grey hat. They have a choice to either respond to the grey hat demands or ignore them. We argue that if the shareholders choose to patch the vulnerability, the business is acting in the interests of the shareholders as it reduces their likelihood of being successfully hacked by a black hat. Without the involvement of the grey hat, the shareholders would remain in the dark, unbeknownst to the vulnerabilities in their system. If vulnerabilities exist, they are likely to be exploited. On this basis, we argue that it is imperative that businesses respond to grey hat’s demands. If one weighs the decision to not patch the vulnerability within the given timeframe against ignoring the grey hat demands and the vulnerability being made public; it is in the shareholders’ interests to not put the business and specific stakeholders’ information and IT systems, networks and infrastructure at a higher risk of being successfully attacked by a black hat, as this can cause economic loss and reputational and psychological damage.

When a black hat ransoms a business, the situation is quite different. For the sake of argument, we assume the intention of the black hat is financial gain. Let us also assume that the black hat installs either a ‘blocker’ or ‘locker’ (Ivanov et al. 2016). In certain circumstances, responding to a black hat’s demands can be in the interest of shareholders for the following reasons: (1) As the business is held to ransom, it might be in the shareholders’ interests to immediately pay the ransom. This might be the case when it is not foreseeable for the business themselves to reverse engineer the attack. Assuming that both parties deliver what has been ransomed and promised, by paying the ransom the business can resume service without the potential collateral damage associated with a data leak (Brey 2007). (2) A study conducted by Datto, Inc. (2018) reveals that ransomware from 2016 to 2017 cost European SMEs £71 M in downtime, with the average ransom ranging between £350 and £1407 (Ismail 2018). If the average ransom is lower than the potential cost of a data breach or leak, and is less than the cost of service stoppage, this leads us to suggest that it is in shareholders’ interests to pay the ransom. (3) Ninety-nine percent of all businesses in Europe are SMEs. SMEs may not have the means nor manpower to reverse engineer a ransomware attack. This leads us to suggest that SMEs (in particular) should attempt to negotiate a lower price with the black hat. Negotiating with ransomware families has been known to successfully reduce the cost of the ransom. Sean Sullivan, a cybersecurity specialist from F-Secure, explains that crypto ransomware works so well that it has become an industry run by families, similar to the way legitimate businesses run (Sullivan 2016). For example, the Cerber ransomware family has a user-friendly website that supports several languages and offers customers convenient support forms so the victim can ask how to get their files back. Sullivan (2016) and his colleagues investigated the customer journey more closely by examining four crypto-ransomware families and find- found that three out of the four families negotiated with the victims of the ransomware attack, offering an average discount of 29% from the original sum demanded (Sullivan 2016). Sullivan and his colleagues also found that the demanded timeline is not set in stone, as 100% of the crypto-ransomware families contacted gave extensions to the deadlines. This leads us to suggest that businesses ought to engage with hackers to negotiate not only the sum of the ransom but the timeframe within which it is expected to be paid.

6.2 Employees

For employees who wish to remain in long-term employment, it is in their interests for the business to remain in business. To do so, companies need to use ICT and have appropriate security defences. Grey hats are acting in the interest of the common good by trying to improve computer security defences. It is thus in employees’ interests for the business to respond to grey hats’ identification of vulnerabilities and patch them.

It is in the employees’ interests for a business to reduce the potential collateral damage associated with a malicious black hat attack. We argue that it is in the interests of employees for businesses to firstly (a) try to find and use a decryption key and not pay the ransom and secondly (b) when decryption keys are not readily available, engage with the ransomware attacker and try to negotiate a lower fee. Both are in employees’ interests, as the first avoids having to pay any financial fee at all and the second, while not ideal, can significantly lower the financial impact that an attack can have on a firm.

6.3 The Local Community

If it is in the interests of the employees for the business to respond and negotiate with grey hats and black hats respectively, so too is it in the interest of the local community. This is based on Engster’s (2011) argument that employees tend to be part of the local community. As a result, the business impact on the local community is channelled through its relations with employees. We interpret this to mean that the interests of employees reflect the interests of the local community, but this is not always the case. For example, the local community might have invested in a business by offering them tax-cuts. This creates a business relationship somewhat similar to the relationship between shareholders and the business, based on the fact that the local community has a financial interest in the business. If the business performs well, the local community can benefit. Performing well in this context is understood as either reducing costs and/or increasing profits. If a business is successful in their endeavours to reduce costs and increase profits, they may be in a position to employ more people and/or expand its range of activities. Both endeavours can have a positive effect on the local community as it can lead to an increase in population flow to the local area, a betterment of services etc. We thus argue that it is in the local communities’ interests for the business to respond and negotiate with grey and black hats respectively.

6.4 Customers

For a customer who expects fast and efficient services, responding to grey hats and black hats is in their interests. In a crypto-ransomware attack in particular, it is in customers’ interests for the business to do everything it can to prevent their private information from being sold or shared with the public. Brey (2007) states that data breaches containing sensitive information can cause psychological harm. If this is true, we argue that it is in the customers’ interests for the business to respond to grey hats to reduce the likelihood of a crypto-ransomware attack. Equally, we argue that it is in the customers’ interests for the business to negotiate with black hats to reduce the likelihood of the customers’ private and confidential information from being sold to an interested third party (Engster 2011).

6.5 Suppliers

In respect of suppliers, they have an invested interest in the targeted business. It is in their interests that companies, with whom they engage and do business with, have a secure and reliable network. We subsequently argue that it is in suppliers’ interests for the targeted businesses to readily respond to grey hats’ demands. In relation to a black hat attack, a stoppage of services and a data breach not only affects the business targeted, it can have a knock-on negative effect on the market. Reducing the impact, longevity and cost of black hat blockers and crypto attacks is as much in the suppliers’ interests as it is in the targeted businesses’ interest. This is based on the fact that the supplier is interested in continuing business as normal and does not gain by being associated with a business who has fallen victim to a ransomware attack. Furthermore, a supplier’s confidential and private information stored on the targeted business’ systems might be leaked, misused or altered by the malicious hackers. It is thus in the suppliers’ interests for the attacked business to resolve the issue as quickly and as responsibly as possible. We argue that this can be achieved by the targeted business responding to the black hats’ ransom by firstly trying to find the decryption and, if none is available, to open up a communication channel with the black hat and try to negotiate a reduced fee.

6.6 Competitors

Competitors are impacted by other businesses operations within their industry. For example, when one company in an industry operates unethically, or in a way that attracts negative attention, competitors can suffer. Additionally, in certain industries associations exist that involve members pooling resources for industry-wide promotions and lobbying efforts. If one business chooses not to abide by the associations’ ethical code, this can damage not only the business themselves but the association and other members of the association. We can apply this notion to a ransomware attack. For example, if one business does not respond to a grey hat’s demands, the business could be argued as passively contributing to a weaker cyber environment. In doing so, the business not only increases their likelihood of being victim to a successful black hat attack, but the business may also be in violation of their association’s ethical code. A violation of ethical code depends on the code itself and the values promoted within it. In other words, the business might be in violation of the ethical code if it encourages members to engage in promoting sustainability for all members of the association through collaboration, communication, co-operation and the sharing of information.

In the case of black hat attacks, it is in all competitors’ interests (especially those who are members of an association) for the business to respond ethically and responsibly. For example, if an association sets a standard that its member must follow when they find themselves victim to a black hat attack, this can create a standard within one industry. Therefore, it is not only in competitors’ interests and the business’s interest to choose an ethical response to black hat attacks, we argue that it is an industry-wide interest. We extend this argument further by contending that it is in competitor’s interests for the business attacked to have the knowhow to not immediately pay the ransom and try to find a decryption key. Thereafter, if a decryption key is not available, the business should engage in negotiation talks with the black hat with a view to lowering the original ransom demanded.

6.7 Hackers

Falk (2014) argues that the grey hat hacker is a black hat in a morally ambiguous state and recommends that grey hacking is a morally wrong action and as such should not be encouraged nor practiced by well-meaning computer professionals”. We do not agree with this line of thinking for the following reasons. Despite both grey hats and black hats ransoming businesses (Yaghmaei et al. 2017), grey hats are interested in improving the information security community by scouring for vulnerabilities. Grey hats afford businesses the opportunity to patch those vulnerabilities before they are exploited by a black hat (Brey 2007). Black hats are not interested in using their skill set for the greater benefit of wider society. They tend to use their skills for malicious and illegal purposes (Radziwill et al. 2015). Black hats also believe in the more traditional hacker ethic that all information should be free and unlimited (Leiwo and Heikkuri 1998). This notion goes against the very idea of intellectual property as it suggests that individuals could and should not be able to benefit from information considered valuable (Brey 2007).

When we consult the ACM Code, it states that all computing professionals have an obligation to minimise the “negative consequences of computing, including threats to health, safety, personal security, and privacy” in addition to minimising the possibility of indirectly and directly harming others (ACM 2018a, b). It might be argued that grey hats follow this code whereas black hats do not. One interesting point made within the ACM Code is that computer professionals should only gain unauthorised access to systems when “there is an overriding concern for the public good” (ACM 2018a, b). This statement could be interpreted as the ACM condoning grey hat behaviour going on the assumption that grey hat’s actions are undertaken out of concern for the public good. Being privy to the fact that grey hats are interested in improving the security of cyberspace and are working in the interests of businesses and wider society, whereas black hats interests are malicious, self-serving and can have detrimental consequences on a business, we argue that it is in businesses’ interest to know the said differences between grey hats and black hats, to respond to grey hat demands, and to explore all options available to them when they fall victim to a black hat attack.

6.8 General Public

From the general public’s view, they trust businesses to keep their information safe and secure (Wenger et al. 2017). In addition, as consumers they want easy access to information without disruptions to services (Yaghmaei et al. 2017). One example of a ransomware attack causing havoc amongst the general public was the WannaCry attack on the National Health Service in 2017 (National Audit Office 2017). From the public’s perspective, resuming service and access is in their interest. This leads us to suggest that it is in the public’s interest for businesses to negotiate with black hats about their demands.

In relation to a grey hat’s demands, it can be argued that the grey hat is extending care to the general public by identifying vulnerabilities in a system or network and forcing businesses to patch them. This argument can be made as grey hats are improving cyberspace for all by making it more secure. The more secure it becomes, the less likely it is that individuals and institutions will be successfully attacked by a malicious hacker. In this way, grey hats are working with businesses to try to reduce the prevalence of malicious attacks. This not only benefits businesses but right down to individuals who use cyberspace for personal use. Therefore, the grey hat is not only extending care to the general public and thus acting morally from a ST care perspective, but the grey hat is fulfilling the third principle of the ACM Code, which states that computing professionals must ensure that the public good is the “central concern during all professional computing work” (ACM 2018a, b). With this in mind, we argue that is in the public’s interest for businesses to respond to grey hats.

7 Conflicts of Interests Between the Stakeholders

We identify two conflicts of interest: (1) between grey hats and the other named stakeholders, and (2) between black hats and the other named stakeholders.

7.1 Grey Hats’ Interests Versus the Other Named Stakeholders’ Interests

-

(1)

Grey hats gain access to systems without the consent of the system’s owner. In this way, grey hats penetrate and manipulate what were otherwise believed to be private and confidential systems. Those systems can contain sensitive and valuable information relating to the other named stakeholders. As these stakeholders are obviously interested in keeping their information safe from unauthorised access, a conflict here arises between the interests of the stakeholders mentioned and the interests of grey hats. Tavani argues that the helpfulness inherent in a hacker pointing out security weaknesses may not outweigh the harm it causes, as activities in cyberspace do inflict harm in the real world. He states that the act of hacking itself undermines privacy, integrity and can compromise the accuracy of information, as all hackers cannot be trusted to freely access and modify information at will (Tavani 2013).

-

(2)

In seeking out vulnerabilities in systems, in rare cases, grey hats can stumble upon unintentional findings that are suggestive of criminal behaviour. In such cases, the grey hat is forced to decide whether they should notify the authorities or the vendor who maintains the business’ systems. If the incriminating information obtained only relates to the dubious behaviour of one individual working within a firm, rather than to the general activities of the firm, should the grey hat notify the business directly, or the authorities? Depending on the nature of the findings, the discovered data could have the potential to damage the business and its shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers and possibly even competitors. A grey hat’s aim is to improve the security of cyberspace, not to incriminate unethical individuals or institutions. Therefore, it is clear that this particular, albeit rare, circumstance can create a conflict of interest between greys hats and the other named stakeholders.

-

(3)

Grey hats want to help users protect against unpatched vulnerabilities and limit the attack surface. Publishing vulnerabilities comes with the risk of weaponising criminals and other parties who may cause harm to organisations and individuals. When a grey hat notifies a business that they have discovered a vulnerability that needs patching within a given time frame and the business fails to patch the vulnerability, it falls to the grey hat to decide how to proceed. Publishing the vulnerability increases public awareness that a particular system or device is insecure. It also provides black hats with the information they need to exploit the vulnerability. Not publishing the vulnerability can lead to a false sense of security. The conflict here arises as both publishing and unpublishing the vulnerability has the potential to benefit or cause harm to the other named stakeholders.

7.2 Black Hats Interests Versus the Other Named Stakeholders’ Interests

-

(1)

Black hats want the highest ransom fee to be paid by businesses whilst it is in shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, competitors and the general public’s interest to pay the lowest fee or no fee. The higher the ransom paid, the more likely it is that black hats can continue with their line of ‘business’. If a solution could be reached without the business paying any fees at all, the interests of the stakeholders that have a financial interest in the firm (shareholders, employees, the local community, customers and suppliers) are upheld. The remaining stakeholders (competitors and the general public) have an interest in a lower or no fee due to the interconnected and interdependent nature of cyberspace. This is based on the notion that any action in cyberspace has a knock-on effect on a device, software, hardware or individual in some way shape or form.

-

(2)

Black hats are interested in their best-case scenario. This can involve receiving the original ransom demanded, not having to share the decryption key so it can be re-used and selling the decrypted data (in a leakware or doxware ransomware attack) to the highest bidder. Businesses should be aware that paying the higher ransom does not guarantee that the black hat will share a decryption key, nor does it guarantee that the data encrypted will not be shared or sold to an interested third party. With this in mind, the worst-case scenario for the business and the other named stakeholders, is in fact the best-case scenario for the black hat, thus illustrating that a clear conflict of interest exists.

-

(3)

It is in a black hat’s interest for the business to pay the original ransom demanded without question. The other named stakeholders do not share this interest. Paying the ransom in this way sets a precedent for all other businesses. In other words, if we apply the principle of universality and all businesses began to do this, it might lead to an expectation that businesses must pay the highest ransom without question nor negotiation. It might also lead black hats to think that their ransoms are too low and encourage them to increase the cost of their demands. Assuming this to be true, businesses who pay the ransom without question nor negotiation are not acting in the interests of the previously named stakeholders due to the potential financial impact and knock-on effect that it might have.

8 Responsibilities of Business

In today’s technologically driven fragile cyber environment, it is clear that businesses have an ethical responsibility to all of their stakeholders to respond to the ransomware demands from both grey hats and black hats in one way or another. At the beginning of this analysis, it appeared that grey hat demands were questionable. However, upon conducting an ethical analysis of the main stakeholders and their interests, it seems that grey hats are acting in the interests of the business and their stakeholders by identifying vulnerabilities and forcing them to patch them, as this improves the business’s computer security defences. We subsequently argue that businesses have an ethical responsibility to their stakeholders to respond to grey hat demands.

Engaging with black hats is not as straightforward. Black hats’ motivations are different, and black hats cannot be trusted to stick to their end of the deal. For example, if businesses choose to pay the original ransom immediately after it becomes known that their data or services have been targeted, the business could not only be left out of pocket from paying the ransom, but their services and data might remain inaccessible despite having paid it.

An additional problem with paying the ransom demanded is that businesses could be accused of aiding or abetting cybercrime. For example, institutions such as Europol’s European Cybercrime Centre, the National High-Tech Crime Unit of the Netherland’s Police and security company McAfee advise companies not to pay the ransom demanded by black hats. They state on their ‘No More Ransom’ website (a website established to try to help victims of ransomware retrieve their encrypted data without having to pay criminals) that by sending money to cybercriminals “you’ll only confirm that ransomware works and there is no guarantee you’ll get the decryption key you need in return” (No More Ransom 2018).

According to Wicks et al. (1994), companies must be adaptable in a fast, ever-changing business environment if they wish to survive and thrive. With this in mind, we encourage businesses to respond readily to ransomware attacks from black hats. In an ideal situation, the faster the decryption key is to hand, the shorter the downtime period. In a situation where a decryption key is not available, and a business explicitly refuses to engage in negotiation talks with the black hat, the business is not only prolonging downtime, they are potentially worsening the financial impact of the attack. Depending on the severity of the attack, such action could affect the long-term sustainability of the firm and the ultimate goal of the firm, which is survival (Engster 2011). Going back to stakeholders’ interests and the understanding that businesses have a responsibility to consider stakeholders’ interests in their decision-making process, an explicit refusal to engage with black hat demands does not align with the interests of all stakeholders simply because of the financial impact of downtime, which can put the survival of the business in jeopardy.

Due to the limitations of this chapter, we assume for the sake of argument that the black hat’s motivations are financial gain and they stick to their end of the ransom (i.e.) when the ransom is paid, they provide the decryption key and do not share or sell the encrypted data. Based on this assumption, we argue that companies have a responsibility to stakeholders (save for black hats) to reduce the potential collateral damage (i.e.) economic, reputational and psychological damage that a ransomware attack can cause. We suggest that businesses can do this by (1) having the knowhow to consult the decryption tools available and (2) when it becomes clear that decryption keys are unavailable, being able to open up negotiation talks with the black hat with a view to reducing the ransom demanded and, thereafter, be willing to pay the ransom at a reduced price.

Our analysis of stakeholder’s interests has brought to light both the interests of the stakeholders and the conflicts of interest that arise in both grey hat and black hat ransomware attacks. After analysing the listed interests and conflicts, we argued from a care perspective that businesses have a responsibility to their stakeholders to communicate and negotiate with grey hats in respect of establishing a reasonable timeframe within which the business can patch the discovered vulnerabilities. Additionally, we argued that businesses have a responsibility to engage with black hats and negotiate a lower ransom when it becomes clear that no decryption key is available. It is noteworthy to mention that in advocating communicating and negotiating with black hats, we are not condoning black hat behaviour; we are simply offering businesses a short-term ethical solution to a much larger problem. The larger problem exists for many reasons which do not fall within the scope of this chapter.

References

ACM (2018a) 2018 ACM Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct: Draft 3. https://ethics.acm.org/2018-code-draft-3. Last access 7 July 2019

ACM (2018b) ACM Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct. https://www.acm.org/code-of-ethics. Last access 7 July 2019

Brey P (2007) Ethical aspects of information security and privacy. In: Security, privacy, and trust in modern data management data-centric systems and applications. Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg, pp 21–36

Bromium (2016) The hidden costs of detetc-to-protect security. https://learn.bromium.com/rprt-hidden-costs.html. Last access 7 July 2019

Burton B, Dunn C (1996) Feminist ethics as moral grounding for stakeholder theory. Bus Ethics Q 6:133–147

CISCO (2018) Risk triage for security vulnerability announcements. https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/about/security-center/vulnerability-risk-triage.html. Last access 7 July 2019

Engster D (2007) The heart of justice: care ethics and political theory. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Engster D (2011) Care ethics and stakeholder theory. In: Applying care ethics to business. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 93–110

ENISA (2018) Cyber security breaches survey 2018 https://www.enisa.europa.eu/news/member-states/cyber-security-breaches-survey-2018. Last access 7 July 2019

European Commission (2018a) Data protection. https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-protection_en. Last access 7 July 2019

European Commission (2018b) Can my company/my organisation be liable for damages? https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-protection/reform/rules-business-and-organisations/enforcement-and-sanctions/sanctions/can-my-company-my-organisation-be-liable-damages_en. Last access 7 July 2019

European Council (2018a) Programs. Certified ethical hacker certification https://www.eccouncil.org/programs/certified-ethical-hacker-ceh/. Last access 7 July 2019

European Council (2018b) Programs. The LPT (Master) training program: advanced penetration testing course. https://www.eccouncil.org/programs/licensed-penetration-tester-lpt-master/. Last access 7 July 2019

European Parliament, (2016) General data protection regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2016.119.01.0001.01.ENG&toc. Last access 7 July 2019

F-Secure, (2018) Incident Response Report. Available at: https://fsecurepressglobal.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/f-secure-incident-response-report.pdf. Accessed 13 July 2018

Falk C (2014) Gray hat hacking: morally black and white, CERIAS tech report, 2004–20. Center for Education and Research in Information Assurance and Security, Purdue University, Lafayette

Freeman R (1984) Strategic management: a stakeholder approach. Pittman, Boston

Freeman R, Gilbert D (1989) Corporate strategy and the for ethics. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Freeman R, Gilbert R (1992) Business, ethics and society: a critical agenda. Bus Soc 31:9–1

Freeman R et al (2010) Stakeholder theory: state of the art. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge/New York

Gilligan C (1982) In a different voice: psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Ismail N (2018) Ransomware costs European SMEs £71M in downtime, reveals report. https://www.information-age.com/ransomware-costs-european-smes-71m-downtime-reveals-report-123470721/. Last access 7 July 2019

Anton Ivanov, David Emm, Fedor Sinitsyn, Santiago Pontiroli (2016) Kaspersky security bulletin. https://securelist.com/kaspersky-security-bulletin-2016-story-of-the-year/76757/. Last access 7 July 2019

Kaspersky Lab (2018) Ready… Or not: balancing future opportunities with future risks. A global survey into attitudes and opinions on IT security. https://media.kaspersky.com/documents/business/brfwn/en/The-Kaspersky-Lab-Global-IT-Risk. Last access 7 July 2019

Leiwo J, Heikkuri S (1998) An analysis of ethics as foundation of information security in distributed systems. In: Proceedings of the thirty-first Hawaii international conference on system sciences, vol VI: Organizational systems and technology track, Watson HJ (ed) IEEE Computer Soc, Los Alamitos, pp 213–222

McReynolds P (2015) How to think about cyber conflicts involving non-state actors. Philos Technol 28(3):427–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-015-0187-x

National Audit Office (2017) Investigation: WannaCry cyber attack and the NHS. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Investigation-WannaCry-cyber-attack-and-the-NHS.pdf. Last access 7 July 2019

No More Ransom (2018) No more ransom. https://www.nomoreransom.org/en/about-the-project.html. Last access 7 July 2019

PECB (2017) Projected cyber attacks in 2018: a matter of when, not if? https://pecb.com/article/projected-cyber-attacks-in-2018%2D%2D-a-matter-of-when-not-if. Last access 7 July 2019

Radziwill, Nicole & Romano, Jessica & Shorter, Diane & Benton, Morgan. (2015). The Ethics of Hacking: Should It Be Taught?

Sullivan S (2016) Got ransomware? Negotiate. https://labsblog.f-secure.com/2016/08/10/got-ransomware-negotiate. Last access 7 July 2019

Tavani H (2013) Ethics & Technology. Controversies, questions, and strategies for ethical computing, 4th edn. s.l.:Wiley

Wenger F et al (2017) Canvas white paper 3 – Attitudes and opinions regarding cybersecurity. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3091920. Last access 7 July 2019

Wicks A, Gilbert D, Freeman R (1994) A feminist reinterpretation of the stakeholder concept. Bus Ethics Q 4(4):475–497

Yaghmaei E et al (2017) Canvas white paper 1 – cybersecurity and ethics. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3091909. Last access 7 July 2019

Acknowledgements

The chapter was created with funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 700540.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, a link is provided to the Creative Commons license and any changes made are indicated. The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Morgan, G., Gordijn, B. (2020). A Care-Based Stakeholder Approach to Ethics of Cybersecurity in Business. In: Christen, M., Gordijn, B., Loi, M. (eds) The Ethics of Cybersecurity. The International Library of Ethics, Law and Technology, vol 21. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29053-5_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29053-5_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-29052-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-29053-5

eBook Packages: Religion and PhilosophyPhilosophy and Religion (R0)