Abstract

The chapter deals with public participation in recovery after earthquakes in the border region of Friuli (NE Italy) and the Upper Soča Valley (NW Slovenia) in 1976 (magnitude 6.4, 6 May; magnitude 6.1, 15 September—the Friuli earthquakes), 1998 (magnitude 6.0, 12 April), and 2004 (magnitude 4.9, 7 July). It highlights the differences in the concepts of the post-earthquake recovery, taking into consideration the different political systems between the two countries (capitalist Italy vs. communist Slovenia in 1976) and changes in recovery after the change of political system in Slovenia (communist Slovenia in 1976 versus capitalist Slovenia in 1998 and 2004). The research is based on a qualitative case study carried out through interviews and comparative analysis in selected settlements. From the strategy of recovery, Italy was characterized by a bottom-up and Slovenia by a top-down approach. According to Arnstein’s ladder, the citizen participation in Italy was at the highest stage of citizen power—citizen control, while Slovenia was characterized by non-participation, tokenism, and was thus at a much lower stage of citizen power, regardless of the political system.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

10.1 Introduction

The wider area along the border between Friuli, Italy, and the Upper Soča Valley, Slovenia, is known for earthquakes with a magnitude exceeding 5.0: These include a 5.3 magnitude earthquake in 1279, 6.5 in 1348, 7.0–7.2 in 1511, 6.2 in 1690, 5.6 in 1788, and 5.4 in 1857 (Vidrih 2008). This chapter discusses the most recent major earthquakes in this area.

The 1976 earthquakes with magnitudes of 6.4 (6 May) and 6.1 (15 September), or an intensity between IX and X and between VIII and IX on the European macroseismic scale (EMS-98), with an epicenter in the Venzone area in Italy claimed 990 lives (Lessi 2016; Pellizzari 2016), and 157,000 people lost their homes (Geipel 1982). There were no deaths in Slovenia, but 12,000 buildings were damaged and 13,000 people were left homeless (Orožen Adamič 1980).

The 1998 earthquake (12 April, the “Easter Earthquake”) with an epicenter in the Krn Mountains in Slovenia had a magnitude of 6 and an intensity between VII and VIII (Gosar et al. 1999; Ušeničnik 1999). Approximately, 4000 buildings were damaged in Slovenia.

The last earthquake that caused damage occurred in 2004 (12 July). It had a magnitude of 4.9 and an intensity between VI and VII. Again, its epicenter was in the Krn Mountains. Nearly, 2000 buildings were damaged in Slovenia (Vidrih 2008; Zorn and Komac 2011) among others also buildings that had already been renovated after the 1998 earthquake.

This chapter highlights the public participation in post-earthquake recovery in various political systems (capitalist Italy vs. communist Slovenia in 1976) and within the same country (Slovenia) after the changes to its political system (communist Slovenia in 1976 vs. capitalist Slovenia in 1998 and 2004).

According to Gamper (2008, p. 240), public participation in issues and decisions connected with natural disasters “could be beneficial; both for experts, to gain in acceptance and divide the share of responsibility … and the public, for integrating their local knowledge … as well as preferences in the decision process.” If allowed, the public can participate in various stages of natural disaster management (Pearce 2003; Kuhlicke et al. 2011) and various types of natural disasters such as mass movements (Mikoš 2011), earthquakes (Omidvar et al. 2010, 2011; Pipan 2011a, b), and floods (Lara et al. 2010; Meyer et al. 2012). Concerning foods, the EU Floods Directive (2007/60/EC) even “recognizes the necessity of public participation in the making of public policy concerning floods” (Lara et al. 2010, p. 2083).

10.2 Methodology

This study is based on a qualitative case study carried out through interviews and comparative analysis in selected settlements (Pipan 2011a). The basic method used was interviews (a similar method was also used in a similar study in Iran after the 2003 earthquake in Bam; Omidvar et al. 2011), which provided firsthand information from the eyewitnesses to the recovery and individuals that participated in it. More than thirty semi-structured interviews were conducted between October 2007 and July 2009. The informants were the former and actual representatives of local and regional administration, inhabitants, experts in construction, and experts in the protection of cultural heritage.

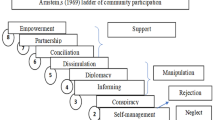

Six cases of settlement renovation are presented. They were ranked on the Arnstein scale (Arnstein 1969) based on public participation in decision-making processes (Thomas 1995). Arnstein (1969) understands citizen participation in decision-making as a categorical factor supporting citizen power provided that all the stakeholders or interested parties participate in the decision-making process. Her citizen participation ladder includes eight rungs (Fig. 10.10): from non-participation (manipulation and therapy) at the very bottom of the ladder, through the levels of “tokenism” that allow the have-nots to hear and to have a voice (informing, consultation, and placation), to various levels of citizen power (partnership, delegated power, and citizen control), which enable citizens to negotiate and engage in trade-offs with traditional power holders and can even allow them to obtain full managerial power (Arnstein 1969; Mušič 1999).

The following three settlements, which were included in the recovery after the 1976 earthquake, were studied in Friuli (Fig. 10.1): Venzone, Portis, and Oseacco. In the Upper Soča Valley, the settlements studied include Breginj (connected with the 1976 earthquake), Drežniške Ravne (connected with the 1998 earthquake), and Čezsoča (in relation to the 1998 and 2004 earthquakes) (Table 10.1).

10.3 Concepts of Recovery After the 1976, 1998, and 2004 Earthquakes

With the legislation that was adopted for recovery after the 1976 earthquakes, the region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia (Italy) transferred the responsibility for post-earthquake recovery to municipalities as the smallest units of local government. The municipalities obtained professional assistance from the earthquake office, but the responsibility for the recovery lay solely with the individual municipalities and their mayors, who represented both the region and the central government in Rome during the post-earthquake recovery. The central government allocated recovery funds to the region, and this, in turn, allocated it to individual municipalities or mayors because they had the best overview of what was happening in the field. During the recovery, there were only two cases of irregularities or misused funds discovered in the entire region; in one (the Municipality of Resia) irregularities only occurred due to a lack of necessary knowledge (Pipan 2011a).

In Slovenia, as in Italy, the responsibility for recovery after the 1976 earthquakes was assumed by the municipalities, which relied on local communities (smaller administrative units within a municipality). The communal assemblies of the municipalities of Tolmin, Nova Gorica, and Idrija established an inter-municipal board that coordinated post-earthquake recovery across the entire Soča Valley (Ladava 1980). The Municipality of Tolmin was most affected; however, because it did not have a majority on the inter-municipal board, its needs may have been overruled by the other two municipalities, which had not been as badly affected and were also more economically developed at the time. The responsibility that the Municipality of Tolmin had did not include sufficient funding for spending on the entire public infrastructure needed, and especially the renovation of cultural heritage, which was shown in the case of Breginj (Sect. 10.4.4).

Selective allocation of recovery funding was also typical at the municipal administrative level. With an area of 939 km2, the Municipality of Tolmin was the largest in Slovenia, which is why there was a clear gap in economic development between the municipal center and its periphery. Spending as part of post-earthquake recovery was thus directed to the central area of the municipality (i.e., Tolmin), followed by the areas of Bovec and Kobarid, where recovery was underway in Breginj (Sect. 10.4.4; Pipan 2011a). The disparity between the periphery and the center was also reflected in the Kobarid area, where the local communities of Breginj and Borjana—that is, distinctly peripheral settlements compared to the center of Kobarid—were most affected. Thus, one could talk about a periphery at four levels (Fig. 10.2): (1) state: the Municipality of Tolmin from the perspective of Slovenia (or at that time Yugoslavia), (2) regional: the Municipality of Tolmin from the perspective of all affected municipalities, (3) municipal: the Kobarid area from the perspective of the Municipality of Tolmin, and (4) local: the local community of Breginj from the perspective of the Kobarid area. Thus, for example, in the local community of Breginj the planned post-earthquake recovery was not fully implemented because of the allocation of funds at the municipal level.

After the 1998 earthquake, the central government supervised the recovery in Slovenia. Thus, a shift in responsibility from the local (municipal) level to the state level is evident after the change of the political system. To this end, the Slovenian government established the National Technical Office in the affected area as a temporary body with regional branches in the municipal seats of Tolmin, Kobarid, and Bovec (during the 1990s, the large Municipality of Tolmin, which supervised the recovery in 1976, was divided into three municipalities; Janežič et al. 2003). In order to avoid a repetition of the concept of recovery in the Breginj area in 1976, during which entire settlements were relocated, the law prioritized recovery at the same location. In order to protect cultural heritage, the recovery of damaged buildings had priority over new construction. The law simplified the administrative procedures connected with building construction as part of the post-earthquake recovery and combined them under the jurisdiction of the National Technical Office, which provided assistance to those affected in handling the required documentation. Before individual projects started being implemented, all of the administrative procedures needed to be completed because the goal was to not repeat the story from 1976, when buildings were renovated or new ones were built, but not entered in the land register for another three decades after the recovery was completed.

10.4 Case Studies

10.4.1 Venzone

Venzone stands out in Italy as an exemplary case of post-earthquake recovery. In order to protect cultural heritage, the entire historical center inside the city walls was proclaimed a cultural monument of national importance in 1965 (Bellina et al. 2006). Post-earthquake recovery was carried out based on two different legal bases. Procedures envisaged in post-earthquake legislation applied to the entire area in Friuli-Venezia Giulia that was affected by the earthquake, whereas in Venzone they only applied to the area outside the city walls. Recovery of the historical center inside the city walls as protected cultural heritage thus took place with an emphasis on preserving architectural cultural heritage (Fig. 10.3).

On the Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation, Venzone is ranked under “citizen control” (Fig. 10.10); this applied to both the areas within and outside the culturally protected historical center. Its residents successfully resisted the manipulation attempts by the municipal authorities, which planned to raze buildings that had not been damaged in the earthquake in order to make space for building a new sports center as part of post-earthquake recovery. Inside the city walls, residents prevented some of their fellow residents from purposely razing some of the buildings that had been damaged in the first earthquake. They reacted the same way a year later, when a series of old damaged houses were razed by an order of the municipal administration. The residents established a special committee, which issued a weekly publication titled “Cjase Nestre” (in Friulian “Our Home”). This publication, which all the residents of the Municipality of Venzone received free, critically evaluated even the smallest step of both the municipal and the regional authorities (Bellina et al. 2006). With a very active and effective bottom-up organization, the residents of Venzone provided support to the Regional Cultural Heritage Office in the critical times of post-earthquake recovery. Venzone, whose renovation was exemplary, is now visited by more than 200,000 tourists a year (Cargnelutti 2018).

10.4.2 Portis

Portis lies on the left bank of the Tagliamento River in the Municipality of Venzone, just three kilometers from the municipal seat. The settlement’s official name is Portis, but because of the 1976 earthquake, the residents distinguish between the old Portis (Portis vecchio) and the new Portis (Portis nuova). The old Portis lies right along the Tagliamento River, whereas the new Portis, which was built after the 1976 earthquakes, lies 1.5 km further north. Due to the risk of rockfalls after the 1976 earthquakes (Fig. 10.4), the authorities decided to relocate the settlement (Fig. 10.5) over the objection of a considerable number of residents. In line with the post-earthquake act, the residents provided the impetus for establishing the new Portis cooperative (La Cooperativa Nuova Portis) for building the settlement at a new location. Through the cooperative, the residents successfully implemented post-earthquake recovery at the lowest, local decision-making level and were the first in Friuli-Venezia Giulia to complete the majority of the recovery work (in 1981). Portis is a good example of how the residents took responsibility for the post-earthquake recovery into their own hands and showed that this was the right choice after the authorities had ordered them to move to a new location (Storia di un paese ricostruito 1992; Pipan 2011a; Cozzi 2017). Due to its relocation, Portis is ranked under “informing” on the Arnstein citizen participation ladder, but its later recovery can be ranked under the highest level: citizen control (Fig. 10.10).

10.4.3 Oseacco

In terms of the Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation, the Municipality of Resia is negatively classified under “citizen control” (Fig. 10.10), thus meaning that the highest citizen participation is not necessary the most suitable solution for earthquake recovery. Even though the new settlement named Lario with prefabricated houses as the most damaged part of Oseacco was already completed in the fall of 1976, recovery in Resia took a very long time. The law assigned responsibility for the recovery to the municipality, but this was too much for the weak local community to handle. The reason for this was a combination of unfavorable circumstances such as a large extent of damage, the peripheral location of the municipality in the mountains, and ineffective management of the recovery, which resulted from overly frequent replacements of ineffective mayors. Thirteen years were lost because of this. The renovation work only resumed in 1990 and ended in 1996, which was twenty years after the earthquake (Madotto 1998). In addition to the problems connected with electing an effective mayor, the negotiations between individual settlements also proved extremely difficult. The settlements that had suffered less damage were suitably renovated, but in Oseacco, which had had the most picturesque architectural heritage in the valley before the earthquake, everyone renovated their houses as they pleased. Thus, an eyesore that mars the overall image of the settlement is what has remained of the settlement formerly styled as “Little Venice.”

10.4.4 Breginj

The situation in the old Breginj was complicated even before the earthquake. Despite the efforts made by the Municipality of Tolmin and the Cultural Monument Protection Institute to preserve the architectural heritage, the local community was divided. After the 1976 earthquakes, the authorities ordered that the residents had to be in new houses by winter. Thus, from the “informing” through the “consultation” levels on the Arnstein’s ladder (Fig. 10.10), an agreement was reached to preserve and renovate only a very small part of the old Breginj (Fig. 10.6). However, due to the lack of funds, this renovation was not carried out until 2004. Based on the public discussion on renovating Breginj that was aired on national television “TV Ljubljana” (nowadays TV Slovenija) in 1983, this example of post-earthquake recovery can be classified under “manipulation” because the program that presented this discussion was censored and, in fact, canceled (Pipan 2011a).

After the 1976 earthquakes, the government did not act as it should have with regard to architectural heritage because it did not have suitable mechanisms in place and sufficient financial resources to protect and renovate cultural heritage of national importance. The local authorities had power only on paper, and their responsibility was too great given the financial resources available.

10.4.5 Drežniške Ravne

Drežniške Ravne was badly damaged in the 1998 earthquake (Fig. 10.7), and the mayor saw a good opportunity to renovate the settlements as part of a comprehensive regulatory plan. The stage in which the plan was being drafted is an example of successful cooperation between the affected residents, the municipality, and the state. On the Arnstein’s ladder, this could be classified under “partnership” (Fig. 10.10). However, in the case of Drežniške Ravne, problems started with the implementation stage of the regulatory plan because there was not sufficient funding available. In addition, residents and the authorities understood the plan differently. Despite the fact that the renovation was successfully completed, it could have been better, taking into account the original plan.

10.4.6 Čezsoča

In Čezsoča (Figs. 10.8 and 10.9), the 2004 earthquake also damaged buildings that had already been renovated after the 1998 earthquake. Čezsoča is an example of a settlement in which the general public started doubting the operation of professional institutions despite its lack of knowledge of earthquake-safe construction. Recovery after the 1998 earthquake was based on the assumption that those affected in the earthquake could not be trusted and that the state had to direct and supervise the renovation in the form of a National Technical Office. The damage to all houses in the village in 1998 amounted to almost one-third of the overall market value (28%) of all real estate in the village (Komac et al. 2011). The 2004 earthquake revealed that a great deal of the construction work that had already been paid and documented as finished had not been carried out at all. This undermined people’s trust in the operation of the recovery system. Čezsoča can be classified under “informing” and partly also under “therapy” on the Arnstein’s ladder citizen participation (Fig. 10.10).

10.5 Discussion and Conclusion

Each case is a story in itself, but the cases described here show that several factors affect the success of post-earthquake recovery. In addition to various political and legislative–administrative contexts, responsible citizens also play an important role. In the case of Venzone, the majority of residents and stakeholders had a positive influence on the preservation of cultural heritage because they reduced the negative impacts of individuals and were successful in resisting the municipal authorities’ desire for a quick post-earthquake recovery, as had occurred in Breginj on the other side of the border. Portis is a good example of how the local community successfully agreed on how to renovate its settlement and also carried out the renovation entirely on its own. The responsibility for carrying out the post-earthquake recovery proved to be too much for the weak local community in the Municipality of Resia. Due to a large amount of damage and ineffective management of the renovation, recovery was only completed after two decades. The case of preserving the architectural heritage of Breginj involved a divided local community, and the municipality’s responsibility for carrying out the recovery was not supported with sufficient government funds. The unwillingness of the authorities to critically evaluate the renovation also stands out in this case because they even censored the television program featuring this issue. Drežniške Ravne is an example of good negotiations with the locals in drafting the regulatory plan for renovating the settlement affected in the earthquake. Unfortunately, due to a lack of funds, the government did not fully implement what was originally a very good regulatory plan. In the case of Čezsoča, the residents’ warnings and discomfort regarding irregularities in the recovery after the 1998 earthquake were only confirmed by the 2004 earthquake.

From the strategy of recovery, the case studies from Italy show a bottom-up approach (Table 10.2), which is based on the tradition of democratic decision-making processes. According to Arnstein’s ladder, the citizen participation is always at the highest stage—citizen control. However, the case study of Oseacco shows that the bottom-up approach and the citizen control stage may not necessarily be a success story—also from the point of preserving the cultural heritage.

In Slovenia, the top-down approach was in effect regardless of the political system. The change of the political system only slightly affected the citizen participation—from manipulation under communism to informing, therapy, and partnership in democratic Slovenia. The change of the political system was, however, reflected in better preserving the cultural heritage (Table 10.2).

In Italy, the residents themselves issued a weekly publication “Cjase Nestre” about the earthquake recovery while contrary in Slovenia more than two decades later the information bulletin about the earthquake recovery was issued by the National Technical Office.

However, the successful “Friuli model” of public participation in earthquake recovery was in Italy not repeated, e.g., Irpinia earthquake in 1980 (Geipel 1982) and Abruzzo earthquake in 2009 (Cozzi 2017). The considerable differences in public participation in earthquake recovery in Italy are the result of cultural differences within the country.

According to Franceschino Barazzutti (Pipan 2011a), at the time the president of the association of municipalities affected by earthquakes and the mayors of earthquake recovery in Friuli (Associazione dei comuni terremotati e dei sindaci della ricostruzione del Friuli) the successful public participation in earthquake recovery in Friuli could today not be repeated. Namely, the region and the state would not be prepared to transfer its powers to municipalities for the bottom-up approach. Even if this would be the case, there is the question if the municipalities with a new generation of politicians with different values than the ones in 1976 would be capable to react and perform in a similar manner.

References

11° censimento generale della popolazione 24. 10. 1971: Dati per comune sulle caratteristichestrutturali della popolazione e delle abitazioni, Provincia di Udine (1973). Istituto Centrale di Statistica, Roma

Arnstein SR (1969) A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Inst Plann 35(4):116–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Arnstein SR (2004) A ladder of citizen participation. http://lithgow-schmidt.dk/sherry-arnstein/ladder-of-citizen-participation.html. Accessed on 12 Feb 2009

Bellina A, De Colle A, Moretti A, Quendolo A (2006) Venzone – La ricostruzione di un centro storico. Bollettino dell’associazione “Amici di Venzone” 35

Cozzi D (2017) Antropologia, disastri e modelli: la lezione di Portis. In: Morandini S, Cozzi D (eds) Portis: La memoria narrata di un paese. Cierre edizioni, Verona, pp 201–225

Cargnelutti P (2018) Un borgo da record: oltre 200 mila turisti nel 2017 a Venzone. Messaggero Veneto (11 February 2018). https://messaggeroveneto.gelocal.it/udine/cronaca/2018/02/10/news/un-borgo-da-record-oltre-200-mila-turisti-nel-2017-a-venzone-1.16462905. Accessed on 27 Mar 2019

Gamper CD (2008) The political economy of public participation in natural hazard decisions—a theoretical review and an exemplary case of the decision framework of Austrian hazard zone mapping. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 8:233–241. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-8-233-2008

Geipel R (1982) Disaster and reconstruction. George Allen & Unwin, London

Gosar A, Živčić M, Cecić I, Zupančič P (1999) Seizmološke značilnosti potresa (Seismological earthquake characteristics). Ujma 13:57–65

Janežič I, Dolinšek B, Kos J (2003) Popotresna obnova Posočja: tehnični postopek in ekonomski vidik prenove stanovanjskih objektov (Post-earthquake renewal in the Soča valley region: technical approach ano economic point of view). Gradb vestn 52:107–113

Komac B, Zorn M, Kušar D (2011) New possibilities for assessing the damage caused by natural disasters Slovenia—the case of the real estate record. Geogr vestn 84(1):113–127

Kuhlicke C, Steinführer A, Begg C, Bianchizza C, Bründl M, Buchecker M, De Marchi B, Di Masso Tarditti M, Höppner C, Komac B, Lemkow L, Luther J, McCarthy S, Pellizzoni L, Renn O, Scolobig A, Supramaniam M, Tapsell S, Wachinger G, Walker G, Whittle R, Zorn M, Faulkner H (2011) Perspectives on social capacity building for natural hazards: outlining an emerging field of research and practice in Europe. Environ Sci Policy 14:804–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2011.05.001

Ladava A (1980) Izhodišča za odpravo posledic potresa 1976 na Tolminskem (Grounds for the elimination of the effects of the 1976 earthquake in Tolminsko region). In: Dolenc J (ed) Potresni zbornik. Temeljna kulturna skupnost, Odbor za ugotavljanje in odpravo posledic potresa, Tolmin, pp 153–186

Lara A, Saurí D, Ribas A, Pavón D (2010) Social perceptions of floods and flood management in a Mediterranean area (Costa Brava, Spain). Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 10:2081–2091. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-10-2081-2010

Lessi D (2016) Friuli, 40 anni dopo spunta un’altra vittima del sisma. La Stampa. http://www.lastampa.it/2016/05/06/italia/cronache/friuli-anni-dopo-spunta-unaltra-vittima-del-sismaHKXFGdzhR8SihsYxBKAmjL/pagina.html. Accessed on 6 May 2016

Madotto A (1998) Resia: Paesi e localita. Circolo Culturale “Rozajanski dum”. Prato di Resia

Meyer V, Kuhlicke C, Luther J, Fuchs S, Priest S, Dorner W, Serrhini K, Pardoe J, McCarthy S, Seidel J, Palka G, Unnerstall H, Viavattene C, Scheuer S (2012) Recommendations for the user-specific enhancement of flood maps. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 12:1701–1716. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-12-1701-2012

Mikoš M (2011) Public perception and stakeholder involvement in the crisis management of sediment-related disasters and their mitigation: the case of the Stože debris flow in NW Slovenia. Integr Environ Assess Manag 7(2):216–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.140

Mušič VB (1999) Civilna družba v urbanizmu med državo in krajevno samoupravo (Civil society in urbanism between state and local self-government). In: Bohinc R, Černetič M (eds) Civilna družba v Sloveniji in Evropi: zbornik razprav. Društvo Občanski forum, FDV, Ljubljana, pp 253–258

Omidvar B, Zafari H, Derakhshan S (2010) Reconstruction management policies in residential and commercial sectors after the 2003 Bam earthquake in Iran. Nat Hazards 54:289–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-009-9468-y

Omidvar B, Zafari H, Khakpour M (2011) Evaluation of public participation in reconstruction of Bam, Iran, after the 2003 earthquake. Nat Hazards 59:1397–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-011-9842-4

Orožen Adamič M (1980) Neposredni učinki potresa v pokrajini (The direct effects of the earthquake in the landscape). In: Dolenc J (ed) Potresni zbornik. Temeljna kulturna skupnost. Odbor za ugotavljanje in odpravo posledic potresa, Tolmin, pp 81–122

Orožen Adamič M, Perko D, Kladnik K (eds) (1995) Krajevni leksikon Slovenije (Settlement lexicon of Slovenia). DZS, Ljubljana

Pearce L (2003) Disaster management and community planning, and public participation: how to achieve sustainable hazard mitigation. Nat Hazards 28(1–2):211–228. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022917721797

Pellizzari G (2016) Dopo quarant’anni spunta un’altra vittima del terremoto del Friuli. Messagero Veneto. http://messaggeroveneto.gelocal.it/udine/cronaca/2016/03/27/news/terremoto-1.13197280?ref=search. Accessed on 27 Mar 2016

Pipan P (2011a) Primerjava popotresne obnove v Italiji in Sloveniji po potresih v Zgornjem Posočju in Furlaniji (Comparing post-earthquake recovery in Italy and Slovenia after the earthquakes in the Soča Valley and Friuli). Dissertation, University of Primorska

Pipan P (2011b) Sodelovanje javnosti v obnovi po naravnih nesrečah na primeru potresov v Furlaniji in Zgornjem Posočju v letih 1976, 1998 in 2004 (Public participation at the recovery after natural disasters on the example of earthquakes in Friuli and Upper Soča Valley in the years 1976, 1998 and, 2004). In: Zorn M, Komac B, Ciglič R, Pavšek M (eds) Neodgovorna odgovornost, Naravne nesreče 2. Založba ZRC, Ljubljana, pp 21–29

Statistični urad Republike Slovenije (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia) (2019) https://www.stat.si/statweb. Accessed on 27 Mar 2019

Storia di un paese ricostruito (1992) Cooperativa edilizia Nuova Portis 1978–1991: Societa Cooperativa a responsabilita limitata “Cooperativa Edilizia Nuova Portis” con sede in Venzone – Frazione Portis, Venzone

Thomas JC (1995) Public participation in public decisions. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Ušeničnik B (1999) Ukrepanje ob potresu. Ujma 13:71–84

Vidrih R (2008) Seismic activity of the Upper Posočje Area. Agencija Republike Slovenije za okolje, Ljubljana

Zorn M (2018) Natural disasters and less developed countries. In: Pelc S, Koderman M (eds) Nature, tourism and ethnicity as drivers of (de)marginalization. Perspectives on geographical marginality, vol 3. Springer, Cham, p 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59002-8_4

Zorn M, Komac B (2011) Damage caused by natural disasters in Slovenia and globally between 1995 and 2010. Acta Geogr Slovenica 51(1):7–41. https://doi.org/10.3986/AGS51101

Acknowledgements

The research was financed by the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) through research core funding Geography of Slovenia (P6-0101) and Heritage on the margins: new perspectives on heritage and identity within and beyond national (P5-0408). The authors would like to thank Ezio Gollino and Silvana Valent from Portis for data and Paola Fontanini and Sandro Domini from Associazione Amici di Venzone for the motivation and the help with providing additional data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pipan, P., Zorn, M. (2020). Public Participation in Earthquake Recovery in the Border Region Between Italy and Slovenia. In: Nared, J., Bole, D. (eds) Participatory Research and Planning in Practice. The Urban Book Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28014-7_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28014-7_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-28013-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-28014-7

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)