Abstract

In times of increased pressure on welfare states, filial caregiving to elderly parents is becoming an increasingly important addition to state organised elderly care. However, certain life course events may cause the relationship between parents and their children to decline, impeding upward intergenerational support. We investigated the effect of divorce on the probability of receiving support from adult children, looking specifically at differences between mothers and fathers. Using Russian data from the 2016 wave of the “comprehensive monitoring of living conditions of the population”-survey, we perform logistic regressions to examine the probability of elderly parents receiving four types of intergenerational support. We found that divorced parents are less likely to receive care than either married or widowed parents. Furthermore, we found evidence that the negative association between divorce and care is stronger for fathers than for mothers. The relative lack of filial caregiving for divorced fathers is likely among the reasons why an increasing group of single elderly men are among those with the highest poverty risks in Russia.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Adult children are an important node in the caregiving network of their elderly parents. Despite the fact that children –within a historical perspective– have always taken care of their parents, there are a number of social and demographical determinants that question this historic self-evidence of family caregiving today (Nave-Herz 2012). On the one hand, European countries experience rapid ageing of the population, which challenges long-term care services (Broese van Groenou and De Boer 2016). The increased life expectancy results in an extended period of long-term care need. As a result, most European societies are adapting their policies taking into account informal caregiving –depending on the context– as either a complement or a substitute for formal care services (Bonsang 2009).

On the other hand, the European population in general is confronted with the process of individualization, resulting in de-standardization of family structures, such as a rise in divorce (Brückner and Mayer 2005). Moreover, the incidence of divorce is rapidly increasing in the group of people aged over 50, a development that has been coined as the “gray divorce revolution” (Brown and Lin 2012). The academic consensus is that parental divorce is detrimental for parent-adult child relationships in general, and especially so for fathers and their adult children (Cooney and Uhlenberg 1990; Daatland 2007; Lye 1996; Saraceno 2008). It is then possible that these weakened ties result in diminished support from adult children to divorced elderly parents. In various studies across different contexts, scholars have noted that the amount of post-divorce contact between fathers and their children declines (Daatland 2007; Kalmijn 2007), their social and caregiving network shrinks (Barrett and Lynch 1999; Dykstra 1997) and they receive less emotional support in comparison to both married and widowed fathers (Aquilino 1994). Consequently, divorced, elderly fathers are at risk of receiving less support from their children.

Because intergenerational support depends on both the familial network and the wider cultural context (Lowenstein and Ogg 2003), Russia presents an interesting setting for the study of the effects of divorce on filial caregiving. First, the term “custody” itself is usually not part of the Russian legal vernacular. It is used to denote residence of the child, but has no legal meaning. Although there are no preferential rights for mothers concerning child residence, the court’s belief that mothers are better suited to look after children results in up to 90% of children staying with their mothers (Khazova 2005; Tretyakova 2018). This implies that children tend to have stronger ties with their mothers than their fathers after divorce. Next, the Russian system for elderly care is highly dependent on personal savings as well as support from family members. Government support is limited and underdeveloped. While this system worked in traditional societies, where intra-family transfers played an important role in the wellbeing of the elderly population, it has become more controversial due to the combined effects of an ageing population and the rise of divorces in families with children. As informal support for the elderly is more rule than exception in Russia, the country provides an excellent opportunity to assess the detrimental effects of weakened ties between parents and their children.

This chapter therefore intends to shed light on the association between partnership status and intergenerational support received by elderly parents in Russia. We look at differences between mothers and fathers, and go beyond a unidimensional care-question by looking into four different types of filial support: (a) financial support, (b) material support, (c) help with housework, and (d) care during illness. We compare elderly mothers to fathers and look for differences between widowhood, divorce and elderly couples who remained married.

Our research extends the knowledge of the field in several ways. While there exists an extensive literature on intergenerational support in Western societies (Bonsang 2009; Brandt et al. 2009; Dykstra 1997; Hämäläinen and Tanskanen 2017; Kalmijn 2012; Silverstein et al. 2006), we expand the current literature to the Russian context, where the question of upward intergenerational support has become prevalent due to sociodemographic changes. With regard to the ageing of the population, almost one-fourth of the Russian population (or 36.7 million of people) is older than the retirement age, which is officially 55 years old for women and 60 years old for men (Russian Federal State Statistic Service n.d.). Due to transformations of the family structure and improvements in medical care over the last 90 years, there has been a growth of the percentage of elderly people in the age structure of the Russian population. Projections show a further increase of the demographic burden on the working population: even (modest) predictions point to a constant increase in the amount of retirees in Russia for at least the next 15 years. Besides an ageing population, the crude divorce rate in Russia has risen to 4.2 per mille since the second half of the twentieth century, which is the highest among European countries.

Next, the focus of previous research has predominantly been on types of caregiving and not care-receiving. According to Saxonberg and Sirovátka (2006), Eastern European countries tend to have a different pattern regarding family policies in comparison with other European societies. Most European regions have a policy history with a shift from familialization towards defamilialization (Saxonberg 2013). This means that the responsibility regarding family policies moves from informal interventions (e.g. children taking up elderly care) towards formal interference (e.g. building a formal safety net for elderly with governmental funding). However, Eastern European countries have evolved differently in the post-Soviet era. As a reaction to the breakdown of the Soviet Union, they have made a reversed movement: from defamilialization towards familialization policies (Saxonberg and Sirovatka 2006). In the context of intergenerational solidarity, this means that informal care has taken a crucial position in Russian society as the formal alternative is now virtually non-existent. When we combine Saxonberg’s defamilialization thesis with the ongoing demographic trends, the simultaneity of both transitions –population ageing and rise in divorce– increases the pressure on caregivers, which might pressurize intergenerational solidarity (Trommsdorff and Mayer 2012).

Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, upward intergenerational support in Russia has not yet been analysed in relationship to marital status, which has likely led to an overestimation of the support the elderly receive from their children. Finally, we combine gender with three types of partnership status and four different types of filial support in order to get a wide overview of support processes in Russia. Our findings can therefore be used as a broad base for future, more specific research into filial caregiving.

2 Theoretical Framework

Social exchange theorists emphasize the importance of reciprocity. They have argued that human behaviour is based on a rational cost-benefit analysis. Social interaction is then in essence the exchange of resources while factoring in (expected) rewards (Coleman 1994). This could suggest that parents who invested more in their children will receive more support in later life. Conversely, this also implies that adult children who expect higher rewards would offer more support to their parents. Both American and European studies have found that the parental investments of mothers, both temporal and emotional, were greater than those made by fathers (Kalmijn 2007; Silverstein et al. 2006). Although fathers’ investments have increased during the last decades, the discrepancy still exists. The reciprocity-hypothesis then implies that fathers will receive less support in later-life. Informal caregiving between kin appears to favour mothers. Indeed, mothers have been found to receive more instrumental, financial, and emotional support from their offspring (Hämäläinen and Tanskanen 2017; Rossi and Rossi 1991; Silverstein and Bengtson 1997).

The common effects hypothesis predicts a further weakening of ties between divorced fathers and children since, in most cases, children reside with their mothers after divorce (Kalmijn 2012; Tretyakova 2018). Although fathers usually continue to be involved in their children’s lives, these engagements are weaker. In light of Russian law practice on child residence after divorce, this point is especially salient. As the vast majority of children reside with their mothers after divorce (Khazova 2005; Tretyakova 2018), this leads to the weakening of father-child relationships. Due to the diminished return of intergenerational transfers after divorce, if a child experiences a decline in the father’s involvement, this results in less frequent support and contact in later-life (Silverstein et al. 2002; Tretyakova 2018). Several studies with regard to intergenerational contact indicate that both the quality and the extent of contact after divorce diminishes, especially for fathers (Kaufman and Uhlenberg 1998; Silverstein and Bengtson 1997; Tomassini et al. 2004). Cooney and Uhlenberg (1990) concluded that the marital history of fathers is decisive for their father-child relationship in later life. Fewer contact means weaker ties, resulting in a decrease of intergenerational support from children.

Furthermore, Kalmijn (2007) has stated that marriage can protect men in terms of intergenerational support. The author refers to the “kinkeeping role” of mothers: keeping the family together by organizing family dinners or by stimulating children to take care of their fathers. The effects of this kinkeeping role are differentiated by marital quality. Offspring of happily married parents usually have a good relationship with both their parents, but in unstable marriages, the quality of one of the parent-child dyads tends to deteriorate as children develop a closer relationship with one of their parents. When an unstable marriage is terminated, the quality of the relationship between the other parent and the child worsens even further (Booth and Amato 1994). This weakening of ties is the consequence of the fact that a parental divorce harms both the horizontal ties between both partners, as well as the vertical relationships between, for example, parent and child (Dykstra 1997). The kinkeeping hypothesis then implies that divorced fathers lose the benefits of marriage, which results in a decline of both intergenerational contact and support (Kalmijn 2007).

Marital disruption can also be the result of a parental death. In the case of widowhood, the extent of intergenerational contact and support changes as well. Whereas the amount of contact is relatively similar between widowed and married parents, previous research has shown that widow(er)s experience more support than married or divorced parents (Barrett and Lynch 1999; Kalmijn 2007). Yet, similarly to divorced fathers, the risk of receiving no care is larger for widowers than widows (Aquilino 1994; de Jong Gierveld and Dykstra 2002). Additionally, although widow(er)s tend to have a larger informal care network as compared to married or divorced parents, widowed fathers live more isolated than widowed mothers, widening the gender gap (Eggebeen 1992).

Taken together, the social exchange theory of reciprocity, the common effects hypothesis and the theory of women’s kinkeeping role all suggest that divorced men are less likely to receive intergenerational support from their children. This leads to three testable hypotheses: (a) fathers receive less care from their children than mothers (H1); (b) divorcees receive less care than either still married parents or widow(er)s (H2); and (c) the interaction between gender and marital status is so that the negative association between divorce and filial care is stronger for men (H3). We hypothesize that these associations are significant after controlling for other relevant determinants of intergenerational support.

The extant literature points to several of these factors that influence the extent of intergenerational support. Firstly, having siblings has been found to be negatively associated with providing intergenerational support (Dykstra et al. 2014). When there are multiple siblings, adult children experience a reduced feeling of responsibility of taking care for their parents. Haberkern et al. (2013) showed that parents are more likely to receive care from an only child. When there are multiple siblings, the type and intensity of care depends on the family constellation. When all siblings are sons, parents are more likely to become institutionalized or helped by in-home carers. When one of the siblings is a female, other siblings expect her to do the majority of the caregiving. Second, increased opportunities for interaction between parents and children that follow from living close to one another was found to improve the extent of support (Bengtson and Roberts 1991). Lastly, earlier research has shown that the extent of care given increases when offspring receive financial transfers from their parents or when they expect a larger inheritance (Brandt et al. 2009). On the other hand, wealthier children have more opportunities to outsource both care- and help tasks, while wealthier parents might not need much aid at all. Similarly, educational attainment may alter the gender gap. The higher educated often hold more liberal attitudes towards gender roles. They may have had the opportunity to work in higher income jobs, which implies that they are more financially stable in later life, in comparison to the lower educated (Ha et al. 2006).

3 Data and Methods

We use data from the 2016 wave of the “comprehensive monitoring of living conditions of the population”-survey. The survey covered all regions of the Russian Federation, but was not conducted in hospitals and nursing homes. The total sample of this survey consists of 134,000 people over the age of 15. From these, a selection was made of men aged 60 and upwards and women ages 55 or more, the respective ages at which people in Russia are allowed to retire. While retirement is not necessarily a point at which people become dependent on others for care due to physical disabilities, it does represent (in most cases) a sharp drop in income. This does mean that our sample likely exists of more healthy women than healthy men. We control for this disparity by not taking into account those respondents who indicated they did not need a particular type of support.

The survey offered information on four types of help the respondents might receive from their non-cohabiting children. These are binary indicators for whether or not the respondents receive that specific type of support from their children. The types of help are: (a) financial aid, (b) material aid, (c) help with housework, and (d) care during illness. Financial aid refers to receiving money from children, while material aid refers to children providing goods for their parents. Possible responses to the question whether they receive either of these types of help were yes, no, or not necessary. For each of the separate types of support between 15% and 25% of the respondents answered that the type of support was “not necessary” and were therefore excluded. Divided by gender, around 5% more men indicated not to need help per type of support.

Respondents were selected on having at least one child aged 15 or more not living in the household. As the data did not allow us to control for higher order marriages, we make the assumption that a married or cohabiting respondent is someone who is still living together with the other parent of this child. This resulted in a total sample of 31,120 respondents, consisting of 31% males. We do not distinguish between marriage and cohabitation for elderly parents, so that someone in the sample that has experienced the dissolution of a partnership with children could either refer to legal divorce or the end of a cohabitational partnership. These divorced or separated parents made up 9% of respondents, versus 35% widowers. The remaining 56% were married or cohabitational partnerships. Because not all widowers or divorcees remain single, we controlled for size of the household by including an indicator for someone living in a single-person household. Of all widowers, 78% were currently single, which was comparable to 76% of the divorcees.

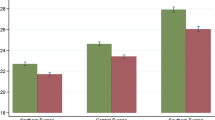

Figure 8.1 shows the descriptive associations by gender and partnership status. Within the group of women, there does not appear to be much difference between care received by those who are divorced or those who are still married (or cohabiting). Widows do indicate they receive more of any of the four types of care from their children. Within the group of men, divorced fathers markedly indicated they receive fewer care than still married fathers, especially help with housework or care during illness. Looking across genders, divorced men receive fewer care than their female counterparts, while at first sight, there are no remarkable differences between the other groups of men and women.

We added several control variables that the extant literature has found to be related to upward intergenerational support. Concerning individual characteristics of the respondent, age was included as a second order polynomial. Mean age of the sample was 68 years old (sd = 8.33), with respondents ranging from 55 to 99 years old. The natural log of income was also included to indicate economic necessity. Mean income of the sample was 15,819 Russian Ruble (sd = 8865).Footnote 1 Next, since being above the legal retirement age does not necessarily mean that the respondents were retired, a separate indicator was included. Just over 80% of the respondents indicated that, during the last year, their main activity was that they were retired. As a final individual indicator, education level was included as three categories: 33% were lower educated (primary education or less), 49% were middle educated (more than primary, no tertiary education), and 19% were higher educated (at least some tertiary education).

Besides individual indicators, we included information on the children as well. First, the number of children aged 15 and upwards was included as a second order polynomial as it is unlikely that each additional child would result in a linear increase of support. The mean number of these children was 1.8 (sd = 0.83). Finally, a proximity indicator for the distance between the respondent and the children was included. The survey asked whether or not any of the non-resident children lived in (a) the same village or city, (b) another village or city, (c) another country, (d) unknown. The proximity indicator was constructed as a dummy variable indicating whether or not at least one child was living in the same village or city. This was the case for 62% of the respondents.

For each of the four dependent variables, two separate logistic regressions were estimated. The first includes all indicators but no interactions between partnership status and gender. In the second type of models, these interactions were included. This allows us to formally test whether or not a model then separates the effects of partnership status by gender performs significantly better.

4 Results

Table 8.1 shows the results from eight logit models. Estimates are presented as odds ratios to facilitate interpretation. Evaluation of the first two hypotheses is done based on the first type of models. Men in general received significantly less support from their children after controlling for individual and child characteristics. Depending on the type of aid, the odds of receiving help are between 1.15 (= 1/0.868) and 1.26 (= 1/0.794) times lower for men than women. These results confirmed our first hypothesis (H1) that intergenerational support, on average, is lower for men than it is for women. Next, partnership status was shown to play a significant role in receiving intergenerational support as well. Net of the association with gender, widowed or married or cohabiting parents received significantly more support than divorced parents, except for financial support, where there was no difference between either married or divorced parents. In terms of magnitude, the differences ranged between 1.3 times higher odds of financial support for widowed parents than divorced parents and 3.1 times higher odds of receiving help with housework for married parents than for divorcees. This partly confirmed our second hypothesis (H2), that divorced parents receive less support than either widowed parents or parents who are still married.

Assessment of the third hypothesis (H3), that fathers suffer from an additional divorce penalty in terms of intergenerational support, is done based on the second type of models. The interaction term shows that negative associations that were found between divorce and receiving filial care is persistent after the inclusion of the interaction terms. The parameter estimates of these interactions show that this association is stronger for men than it is for women. Additionally, model fit statistics show that models that include the interaction perform significantly better than those who do not, and this for all four types of support. The third hypothesis was therefore confirmed. Since interpreting logit models with categorical interactions becomes unwieldy, marginal effects of gender on receiving support from children were calculated for all partnership types. Figure 8.2 shows that divorced men were between around 15 and 20 percentage points less likely to receive intergenerational support. These decreases in probability were significantly higher than for men in other partnership types.

As far as the control variables are concerned, the models showed several other interesting results. First, the polynomials for age showed a decreasing association with financial aid, but an increasing one with help in the housework. Second, income was significantly associated with a higher probability of receiving financial or material support. It was on the other hand negatively related to help with the housework, and not significantly associated with care during illness. Educational attainment on the other hand was found to be negatively related to care during illness and –to a lesser extent– help with the housework, positively related to financial support, but no significant association was found with material support. Next, having children living in the same village or city was negatively related to receiving financial aid, but positively related to the other three types. Both being retired and being in a single-person household was associated with receiving more support, regardless the type. Last, as was expected, having more non-resident children was negatively associated with receiving aid.

5 Discussion

Russia’s traditional distribution of family roles results in stronger ties between mothers and their children than it does for fathers. These weakened ties wane even further after divorce, as Russian law practice usually results in children staying with their mothers (Khazova 2005). At the same time, lack of state provided social protection in Russia means that the elderly are highly reliant on personal savings and financial support from family members (Saxonberg and Sirovátka 2006). Taken together, it is possible that especially divorced elderly men are lacking in terms of intergenerational support from their children. As the single elderly already make up one of the most impoverished groups in Russia, this problem becomes even more prominent. We examined this issue by comparing three partnership statuses (marriages, dissolved partnerships, and widowhood), further subdivided by gender in terms of intergenerational support.

Using data from the 2016 wave of Russia’s “comprehensive monitoring of living conditions of the population”-survey, we used logistic regression models to look at the association between gender and the reception of four types of intergenerational support: (a) financial support, (b) material support, (c) help with housework, and (d) care during illness. We find that, as we hypothesized, divorced elderly men were the least likely to receive any of these four types of support from their non-resident children. While there was both a gender dimension –elderly men were less likely to receive support–, and a partnership dimension –divorcees receive less support than widow(er)s or married parents–, interaction effects between gender and partnership type were also highly significant. On average, elderly divorced men were between 15 and 20 percentage points less likely to receive any of the four types of support that were tested. These results are in line with Pezzin and Schone (1999), who found similar results for the United States, but we expand on this research firstly by comparing both to married parents and widowers, and secondly by looking at a wider range of types of intergenerational support.

The found gendered differences in receiving support are in line with the reciprocity-thesis, which suggests that men receive less care due to smaller parental investments during their offspring’s childhood (Kalmijn 2007; Silverstein et al. 2006). In addition to that, we found that there are diminished returns of intergenerational transfers after divorce, which is in line with Silverstein et al. (2002). We also expand on quality of contact-research (Kaufman and Uhlenberg 1998; Silverstein and Bengtson 1997; Tomassini et al. 2004) by showing that there is an extra penalty for divorced fathers in terms of actual support.

Although our research points towards strong evidence of problematic disengagement between divorced elderly fathers and their children, there are several limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional nature of the survey, we are unable to make any causal claims. Although we include important covariates that might also explain the lack of support from children, there are still a host of unobserved factors that could also play a role, not in the least personality traits of both the respondents and their children. Our results should therefore be considered of a more descriptive, rather than causal nature. Furthermore, our four indicators of assistance are measured as incidence rather than intensity. We are therefore unable to say something about whether or not the provided assistance is sufficient.

Secondly, one of the major limitations of our study is that we have no (reliable) information on many individual characteristics of the caregiving children. Gender, income, educational attainment, health status, employment are all factors that play a role in how much care children are willing or able to give. Unfortunately we have no data on most of these, and can only proxy others. We resolve this as much as possible by using and interpreting known proxies such as parental education and income.

Third, since we only have information on socioeconomic indicators for the parents, controlling for financial status of the children is imperfect at best. Both income and educational attainment of the parent showed positive associations with receiving financial and material support, but negative or no association with housework or care during illness. Theoretically, this is what one would expect if these indicators are a proxy for the children’s income level. The results we find here can however be due to either the prospect of inheritance for higher incomes or stress factors for lower incomes making it so that support for their parent(s) diminishes.

Next, while we have somewhat detailed information on partnership status, we were unable to distinguish whether or not the marital or cohabitational status of the respondents concerned first marriages or not. It is therefore possible that those who indicated they were married had actually been divorced before. While we were able to control for single person households, this control is imperfect. Future research needs to account for higher order marriages in order to obtain more accurate estimates. Due to the nature of the survey question on partnership status, our results are merely an approximation, since only one option could be chosen. Similarly, we could not identify whether or not those who were divorced or widowed, were now living with a new partner. It is possible that the need for help is lower for this group, provided that their partner is healthy. Again, we control as best as we can by adding both the indicator for living in a single-person household as well as by leaving out those who replied that they did not need a particular kind of help. This problem should, however, be addressed in further research with more detailed information.

As a final limitation, the divorced might make up a select group in terms of care needs. However, since those respondents who indicated that they didn’t need that specific type of care were excluded from those models, we reduce the probability of this type of selection bias. Again, this measure is imperfect, as traditional social norms might hinder –especially men– in admitting they need assistance. Since it is plausible that mostly those who do not receive support would choose the option provided in the survey to say that they do not need assistance, the negative associations found for divorced men might actually still be underestimated.

Taken together, our results offer important insights in the precarious situation single elderly Russian men find themselves in and raises important questions for future research. Whether or not the associations found in this study are due to an actual penalty for divorced men, or merely the result of bias due to unobserved heterogeneity is a matter that needs to be addressed, preferably using more extensive longitudinal data. What the effect of this reduction in intergenerational support is on financial or subjective wellbeing, are important issues that require further attention. We only looked at the incidence of support. Future research into the extent of support is therefore necessary to completely understand the gravity of the issue. As an increasing group of single elderly men are among those with the highest poverty risks in Russia, our findings do point towards the need for either reform of divorce laws to strengthen the ties between fathers and children or expansion of social services to deal with the negative consequences of this deficiency of intergenerational support.

Notes

- 1.

To put this into context, public opinion research showed that the perceived line of poverty was 11,173 rubles in 2015 and 15,506 rubles in 2017. This is the monthly income per person that Russians consider too low to cover every day needs (Davidova 2017).

References

Aquilino, W. S. (1994). Later life parental divorce and widowhood: Impact on young Adults’ assessment of parent-child relations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 56(4), 908–922. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/353602. https://doi.org/10.2307/353602.

Barrett, A. E., & Lynch, S. M. (1999). Caregiving networks of elderly persons: Variation by marital status. The Gerontologist, 39(6), 695–704.

Bengtson, V. L., & Roberts, R. E. (1991). Intergenerational solidarity in aging families – An example of formal theory construction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53(4), 856–870. https://doi.org/10.2307/352993.

Bonsang, E. (2009). Does informal care from children to their elderly parents substitute for formal care in Europe? Journal of Health Economics, 28(1), 143–154. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167629608001252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.09.002.

Booth, A., & Amato, P. R. (1994). Parental marital quality, parental divorce, and relations with parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 56(1), 21–34. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/352698. https://doi.org/10.2307/352698.

Brandt, M., Haberkern, K., & Szydlik, M. (2009). Intergenerational help and care in Europe. European Sociological Review, 25(5), 585–601. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcn076.

Broese van Groenou, M. I., & De Boer, A. (2016). Providing informal care in a changing society. European Journal of Ageing, 13(3), 271–279. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-016-0370-7.

Brown, S. L., & Lin, I.-F. (2012). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990–2010. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 67(6), 731–741.

Brückner, H., & Mayer, K. U. (2005). De-standardization of the life course: What it might mean? And if it means anything, whether it actually took place? Advances in Life Course Research, 9, 27–53. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040260804090021. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-2608(04)09002-1.

Coleman, J. S. (1994). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cooney, T. M., & Uhlenberg, P. (1990). The role of divorce in men’s relations with their adult children after mid-life. Journal of Marriage and Family, 52(3), 677–688. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/352933. https://doi.org/10.2307/352933.

Daatland, S. O. (2007). Marital history and intergenerational solidarity: The impact of divorce and unmarried cohabitation. Journal of Social Issues, 63(4), 809–825. Retrieved from https://spssi.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00538.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00538.x.

Davidova, N. (2017). Poverty in Russia. In Poverty and social exclusion in the New Russia (pp. 63–91). London: Routledge.

de Jong Gierveld, J., & Dykstra, P. A. (2002). The long-term rewards of parenting: Older adults’ marital history and the likelihood of receiving support from adult children. Ageing International, 27(3), 49–69. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-003-1002-z.

Dykstra, P. A. (1997). The effects of divorce on intergenerational exchanges in families. The Netherlands Journal of Social Sciences, 33(2), 77–93.

Dykstra, P. A., van den Broek, T., Muresan, C., Haragus, M., Haragus, P.-T., Abramowska-Kmon, A., & Kotowska, I. (2014). State-of-the-art report: Intergenerational linkages in families.

Eggebeen, D. J. (1992). Family structure and intergenerational exchanges. Research on Aging, 14(4), 427–447. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027592144001.

Ha, J.-H., Carr, D., Utz, R. L., & Nesse, R. (2006). Older adults’ perceptions of intergenerational support after widowhood: How do men and women differ? Journal of Family Issues, 27(1), 3–30.

Haberkern, K., Schmid, T., & Szydlik, M. (2013). Gender differences in intergenerational care in European welfare states. Ageing and Society, 35(2), 298–320. Retrieved from https://www.cambridge.org/core/article/gender-differences-in-intergenerational-care-in-european-welfare-states/3B15693E1560C36562975449C86FE825. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X13000639.

Hämäläinen, H., & Tanskanen, A. O. (2017). Intergenerational transfers towards adult children and elderly parents (Working Papers on Social and Economic Issues 14/2017). Turku Center for Welfare Research.

Kalmijn, M. (2007). Gender differences in the effects of divorce, widowhood and remarriage on intergenerational support: Does marriage protect fathers? Social Forces, 85(3), 1079–1104. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2007.0043.

Kalmijn, M. (2012). Long-term effects of divorce on parent–child relationships: Within-family comparisons of fathers and mothers. European Sociological Review, 29(5), 888–898.

Kaufman, G., & Uhlenberg, P. (1998). Effects of life course transitions on the quality of relationships between adult children and their parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60(4), 924–938. https://doi.org/10.2307/353635.

Khazova, O. A. (2005). Allocation of parental rights and responsibilities after separation and divorce under Russian Law. Family Law Quarterly, 39(2), 373–391.

Lowenstein, A., & Ogg, J. (2003). Old age and autonomy: The role of service systems and intergenerational solidarity. Retrieved from Israel.

Lye, D. N. (1996). Adult child–parent relationships. Annual Review of Sociology, 22(1), 79–102.

Nave-Herz, R. (2012). European families’ care for their older members–A historical perspective and future outlook. In H. Bertram & N. Ehlert (Eds.), Family, ties, and care: Family transformation in a plural modernity (pp. 255–270). Farmington Hills: Barbare Budrich Publishers.

Pezzin, L. E., & Schone, B. S. J. J. o. H. R. (1999). Intergenerational household formation, female labor supply and informal caregiving: A bargaining approach. Journal of Human Resources, 34, 475–503.

Rossi, A. S., & Rossi, P. H. (1991). Of human bonding: Parent-child relations over the life course. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Russian Federal State Statistic Service. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.gks.ru

Saraceno, C. (2008). Families, ageing and social policy: Intergenerational solidarity in European welfare states. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Saxonberg, S. (2013). From defamilialization to degenderization: Toward a new welfare typology. Social Policy & Administration, 47(1), 26–49. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00836.x.

Saxonberg, S., & Sirovatka, T. (2006). Seeking the balance between work and family after communism. Marriage & Family Review, 39(3–4), 287–313. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v39n03_04.

Saxonberg, S., & Sirovátka, T. (2006). Failing family policy in post-communist Central Europe. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 8(2), 185–202. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/13876980600682089.

Silverstein, M., & Bengtson, V. L. (1997). Intergenerational solidarity and the structure of adult child-parent relationships in American families. American Journal of Sociology, 103(2), 429–460.

Silverstein, M., Conroy, S. J., Wang, H., Giarrusso, R., & Bengtson, V. L. (2002). Reciprocity in parent–child relations over the adult life course. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 57(1), S3–S13. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.1.S3.

Silverstein, M., Gans, D., & Yang, F. M. (2006). Intergenerational support to aging parents: The role of norms and needs. Journal of Family Issues, 27(8), 1068–1084. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0192513X06288120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x06288120.

Tomassini, C., Kalogirou, S., Grundy, E., Fokkema, T., Martikainen, P., Van Groenou, M. B., & Karisto, A. (2004). Contacts between elderly parents and their children in four European countries: Current patterns and future prospects. European Journal of Ageing, 1(1), 54–63.

Tretyakova, E. (2018). Elderly fathers in Russia after divorce: Gender differences in the intergenerational transfers. 6(1), 1–21. Retrieved from https://journals.co.za/content/journal/10520/EJC-116d6b5f3c. https://doi.org/10.25159/2412-8457/2839.

Trommsdorff, G., & Mayer, B. (2012). A cross-cultural study of intergenerational relations: The role of socioeconomic factors, values, and relationship quality in intergenerational support. In H. Bertram & N. Ehlert (Eds.), Family, ties, and care: Family transformation in a plural modernity (pp. 315–342). Farmington Hills: Barbara Budrich Publishers.

Acknowledgement

This chapter benefited from the support of the Centre for Population, Family and Health (CPFH) at the University of Antwerp and the Flemish Agency of Innovation and Entrepreneurship (Grant number: 140069), which enabled Open Access to this chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Maes, M., Thielemans, G., Tretyakova, E. (2020). Does Divorce Penalize Elderly Fathers in Receiving Help from Their Children? Evidence from Russia. In: Mortelmans, D. (eds) Divorce in Europe. European Studies of Population, vol 21. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25838-2_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25838-2_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-25837-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-25838-2

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)