Abstract

Strong stakeholder and actor engagement in the development of diverse environment and nature-related policies are an important component to ensure successful design and implementation of measures for achieving the set policy objectives. Many social methods are tested and applied in policy planning; however, the key issue is still to explore the most adequate and successful approaches and methods for those policies that require multi-scalar and cross-sectoral approaches for the stakeholder involvement processes, like water or FRM policies.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Strong stakeholder and actor engagement in the development of diverse environment and nature-related policies are an important component to ensure successful design and implementation of measures for achieving the set policy objectives. Many social methods are tested and applied in policy planning; however, the key issue is still to explore the most adequate and successful approaches and methods for those policies that require multi-scalar and cross-sectoral approaches for the stakeholder involvement processes, like water or FRM policies.

River ecosystems provide multiple benefits for society, defined also as ecosystem services. The European Union Biodiversity Strategy adopted in 2010 has determined Task 2 to be to maintain and restore ecosystems and their services by including green infrastructure in spatial planning and restoring at least 15% of degraded ecosystems by 2020. The objective of the EU Floods Directive adopted in 2007 is the establishment of a framework for measures to reduce risks of flood damage, including flood prevention, protection and preparedness. The Floods Directive mentions that a flood management plan shall consider where possible the maintenance and/or restoration of floodplains, as well as measures to prevent and reduce damage to human health, the environment, cultural heritage and economic activity. Although, there is an interlink between both policy objectives, a key challenge is how EU policies are implemented via planning and management schemes at national, regional and local levels, respecting ecological, social and economic conditions.

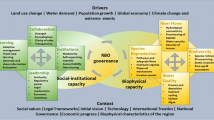

Nowadays spatial, land use or development planning can no longer be performed without the involvement of society and different stakeholder groups. This is ensured by the Aarhus Convention (UNECE 1998), which established a right of the public to participate in environmental decision-making. People have a right to express their opinion or comment; consequently; they have an opportunity to influence decision-making that might be driven by economic profits and unfavourable for nature conservation or quality of life. A number of cases have been collected and presented by the UNECE Aarhus CLEARINGHOUSE for Environmental Democracy (Justice and Environment—European Network of Environment Law Organizations 2013). In order to achieve optimal planning solutions, various biophysical, social and economic methods shall be applied depending on the scale and context of the project described by Warner and Damm (this volume). A scientific approach to the problem solving, evidence and knowledge-based planning process are acknowledged and utilised more frequently by practitioners.

The relocation of the dike on the river Elbe (near Lenzen, Brandenburg) presents the project that was launched in the 2000s before the adoption of the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2020 targets; the Floods Directive was in the drafting stage then. The project was definitely innovative in those days and has provided an input for other locations, for example, in Germany and Poland. Therefore, the experiences and knowledge gained during such a project as the dike relocation at the Elbe is rather unique and valuable for all stakeholders. Ex-post monitoring of nature and water status provides evidence for the effectiveness of such measures in the short and long term respectively and thus potential for its replication.

Driven by nature conservation policy, in particularly, restoration of floodplains, relocation of a dike causes significant impact on water resources, which demands a complex and integrated planning approach. Floodplain restoration improves river hydro-morphology, which is one of the key components to assess the water status according to the EU Water Framework Directive. Recognising synergies and multiple benefits between nature conservation policies, flood protection policies and socio-economic benefits is a very important success factor in achieving desired goals. Several studies have already addressed the synergies between the nature, water and flood risk policies of the EU to achieve the best for rivers and people (EEA 2015; Evers 2016; Ignar and Grygoruk 2015; Schindler et al. 2016). However, less attention is paid to whether and how the EU and national policy objectives are shared at the regional and local level. Are there synergies or conflicts between the governmental levels and how research can support to achieve policy coherence?

Multifunctional landscapes represent also a higher degree of diversity among stakeholders to be involved in policy planning and implementation process. The case area represents rather monofunctional agricultural landscape dominated by grasslands. The key stakeholder was one local agricultural holding company managing almost the entire case study area and demonstrated a positive attitude towards the initiative. Moreover, its loss was compensated financially. In the majority of planning cases, fragmented patterns of land ownership present notable challenges for policy makers and constraints for enhancing development towards NBS at a larger scale (Kabisch et al. 2016; Wamsler et al. 2017). How much of the success of a proposed green infrastructure project depends on the method selected to run the stakeholder process? A variety of tools and techniques are available, but which are most effective and flexible? Can communication and awareness raising activities deliver landowner acceptance? The project was implemented in the protected area—a biosphere reserve where people are used to certain demands imposed by nature conservation. Is this one of the success factors for selecting a site for innovative measures?

The case highlights the importance of the overall acceptance of a large-scale infrastructure project, as it encompasses not only farmland but creates change in the rural landscape. Therefore, stakeholder involvement and communication were organised beyond the group of directly impacted stakeholders, such as landowners whose estates are in the main focus. A survey carried out to assess stakeholders’ attitude towards the project illustrates an increasing acceptance of the project. Amongst others, the tourism sector has been identified as one of the stakeholder groups in the project area assessing the project positively.

Data and hydrological models and involvement of research and monitoring institutes to support the planning process with evidences about the impact on water levels in the local area was another core of the project. Monitoring effects after the reallocation of the dike proved that the peak flows are reduced and water is retained in the space allocated for the river. Nowadays, effectiveness of the flood retention or river restoration measures is monitored and assessed as the restoration projects are mainly financed by public funding. For example, the project co-financed by the EU LIFE Programme 2014-2020 shall implement monitoring activities to assess the impact of implemented actions (Regulation [EU] No. 1293/2013).

Water retention measures are gradually implemented at various scales and deliver numerous social, economic and environmental benefits. Assessing and valuing multiple benefits requires diverse and flexible methodologies from different disciplines; thus research teams shall be built to cover the competencies and skills of a interdisciplinary nature surrounding the topic. Moreover, the assessment results concerning the benefits shall be presented in targeted and tailored ways as different stakeholder groups have their own value systems. Sharing policy goals between various government layers and stakeholder groups is not self-evident; therefore it is important to collaborate across levels and interest groups.

References

European Environment Agency (EEA) (2015) Flood risks and environmental vulnerability Exploring the synergies between floodplain restoration, water policies and thematic policies, p 78

Evers M (2016) Integrative river basin management: challenges and methodologies within the German planning system. Environ Earth Sci 75:1085. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-016-5871-3

Ignar S, Grygoruk M (eds) (2015) Wetlands and water framework directive protection, management and climate change. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13764-3

Justice and Environment—European Network of Environment Law Organizations (2013) Public participation in spatial planning procedures: comparative study of six EU member states. https://aarhusclearinghouse.unece.org/resources. Accessed 28 Dec 2018

Kabisch N, Frantzeskaki N, Pauleit S, Naumann S, Davis M, Artmann M, Zaunberger K (2016) Nature-based solutions to climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban areas: perspectives on indicators, knowledge gaps, barriers, and opportunities for action. Ecol Soc 21(2):39

Regulation (EU) No 1293 (2013) of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013 on the establishment of a Programme for the Environment and Climate Action (LIFE) and repealing Regulation (EC) No 614/2007 Text with EEA relevance. OJ of the EU. L 347:185–208

Schindler S, O’Neill FH, Biró M et al (2016) Multifunctional floodplain management and biodiversity effects: a knowledge synthesis for six European countries. Biodivers Conserv 25(7):1349–1382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1129-3

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (1998) Convention on access to information, public participation in decision-making and access to justice in environmental matters (Aarhus convention). Available via DIALOG. http://www.unece.org/env/pp/treatytext.html

Wamsler C, Pauleit S, Zölch T, Schetke S, Mascarenhas A (2017) Mainstreaming nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation in urban governance and planning. In: Nature-based solutions to climate change adaptation in urban areas. Springer, Cham, pp 257–273

Acknowledgements

Open access of this chapter is funded by COST Action No. CA16209 Natural flood retention on private land, LAND4FLOOD (www.land4flood.eu), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Veidemane, K. (2019). Commentary: Reflection on Governance Challenges in Large-Scale River Restoration Actions. In: Hartmann, T., Slavíková, L., McCarthy, S. (eds) Nature-Based Flood Risk Management on Private Land. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23842-1_20

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23842-1_20

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-23841-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-23842-1

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)