Abstract

In Finland, energy policy is in transition towards integrating energy projects in broader sustainability, liveability and innovation contexts. While energy saving has been pursued for decades, it is now part of a broader tendency in urban planning to promote sustainable lifestyles. Transition manifests in local actors’ redistribution of power, challenging conventional ways of infrastructure development, forging new networks, and seeking novel solutions. The experimental case presented in the chapter, Smart Kalasatama, shows that local governments are close to citizens and, therefore, can influence the conditions for sustainable consumption and quality of life. Although they have an important role in energy policy, they still might lack the resources, expertise and the power to innovate, to evaluate projects, and in particular, to scale up innovative practices.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Finnish energy policy is undergoing a period of transition. Previously, policy focused on the needs of industry, which consumes almost half of all the energy used in the country (Statistics Finland 2018a). The current government aims to increase renewable energy production to more than 50%, phase out coal and halve the use of mineral oil (MoEE 2017). These developments place new challenges on energy policy, where among other issues, energy provision in urban areas has re-emerged as an issue, after more than half a century of stability. For example, the envisaged coal phase-out problematizes the district heating system of cities like Helsinki, where district heating is still largely produced with coal-fired combined heat and power (CHP) combustion.

Home heating and domestic electricity use have been subjects of energy efficiency policy, but not at the top of the energy policy agenda until recently. A recent development is the increasing engagement of cities and rural municipalities in climate policy, featuring several nationwide programmes in which cities and municipalities have committed to climate targets and engaged in a joint search for new solutions to decarbonize the built environment (Mickwitz et al. 2011).

This penultimate chapter highlights how Finnish SECIs reflect recent developments in Finnish energy policy. The most recent SECIs are largely locally based, combine energy saving with other concerns, and aim to develop combinations of technical and social solutions from the bottom up.

Socio-Material Dynamics of Household Energy Use in Finland

Finnish residential buildings are relatively energy efficient, because about 75% of the building area was constructed after the 1970s (Statistics Finland 2018a), when energy efficiency requirements were tightened. Owing to the high level of insulation and the wide diffusion of district heating, Finns are accustomed to stable indoor environments and well-functioning, automatized systems. Like other Nordic countries, average indoor temperatures are rather high (about 21 °C) in Finland (Karjalainen 2009).

However, there are two distinct cultures of home heating in Finland. Finnish apartment buildings are mainly served by district heating. These buildings (both owner-occupied and rented) are collectively managed and billed for district heating as one unit. Residents do not pay individually for their heating—rather, billing for space heating is by square meters (Matschoss et al. 2013). Apartments are equipped with thermostats, making the heating to some extent adjustable, but residents rarely adjust their heating systems (Karjalainen 2009). Until now, district heat has been relatively cheap in large cities due to the widespread use of CHP. Because of this, city dwellers in particular are not too concerned about energy costs.

Finnish detached houses, making up 55% of the residential building area (Statistics Finland 2019), are not usually served by district heating. Direct electric heating is still the most common heating source, often coupled with fireplaces. However, heat pumps have rapidly gained ground. About 900,000 heat pumps have been sold in Finland, providing about 15% of residential heat consumption (SULPU 2019), reflecting the Finns’ propensity to rapidly adopt technological novelties. Energy costs are a much larger concern in detached houses than in apartments, especially for residents with electric or oil heating. Indeed, while energy poverty is relatively rare in Finland, rural elderly people with outdated heating systems are vulnerable, since it is difficult to afford major heating system investments in declining rural areas (Runsten et al. 2015).

Saunas are a distinct Finnish cultural peculiarity. Nevertheless, compared to space heating and domestic hot water, saunas are not a major consumer of energy (Statistics Finland 2018a), even though there are 2 million of them. However, since most modern saunas in cities are powered with electricity, they contribute to peak electricity (Järventausta et al. 2015). Individual saunas started to become a standard feature also in apartments, though this trend is declining in cities due to space constraints. In Helsinki, public saunas have made a comeback, reflecting a wider trend of new urbanism, which emphasizes shared services and amenities, including traditional bricks-and-mortar based, as well as new digital solutions.

Energy Policy in Finland

Finnish energy policy is in transition. For decades, policy focused on the needs of industry, which consumes more than 40% of all the energy used in the country (Statistics Finland 2018b). The share of renewable energy has grown steadily since the late 1970s, but much of it still comes from forest residues used by the pulp and paper industry. However, policymakers have gradually grasped that other renewable energy sources need to be developed, and increasing support has been directed to the development of wind power. Renewable energy amounted to 36% of the total energy production in 2017 (Statistics Finland 2018c). The current government aims to increase renewable energy sources to more than 50% and increase domestic energy provision to more than 55% by 2030. Additionally, Finland aims to phase out coal and halve the use of mineral oil (MoEE 2017). These developments place new challenges on energy policy. Among others, the envisaged coal phase-out challenges the district heating system of cities like Helsinki, where a large share of district heating is produced with coal-fired CHP combustion. This has been a cheap and reliable source of energy for decades, and when introduced, it cleaned up the air in cities (Apajalahti 2018). However, bioenergy based CHP is not deemed feasible for Helsinki—hence, the capital city is plunged into a search for new heating solutions: ideally ones that combine the flexibility and amenity of district heating with fossil-free energy sources like heat pumps (Rinne et al. 2018).

The dominant approach to energy has emphasized technological advances. Indeed, energy efficiency and renewable energy have gained momentum from the notion that Finnish export industries might benefit from innovation. There is growing consideration for behavioural, situational and systemic approaches, but none of these has yet systematically permeated the energy policy mindset (Karhunmaa 2018; Haukkala 2018).

Local authorities have an important, but hitherto somewhat neglected role in energy policy. Municipalities own a large share of the energy production and distribution system. Moreover, municipalities have an important role in delivering energy efficiency policies through land use planning, detailed city plans, and implementation of the requirements set out in the building code. Moreover, large cities develop land for construction and allocate it to construction companies, and can place requirements on new buildings through land release requirements. For example, they can place their own more stringent requirements concerning energy efficiency or building systems that enable residents to control their energy use.

Energy companies have a responsibility to provide energy advice to their customers. Virtually all Finnish electricity consumers have automatic meter reading installed, so most households can view their historical and comparative electricity consumption data online in almost real time. There are also several developments ongoing in developing smart district heating systems. Demand response (flexible use of heat and power depending on supply and demand) has become a hot topic in quite recent years, since it is considered necessary to prepare for a large increase in intermittent power production (Annala et al. 2018).

Citizens are highlighted in policy rhetoric (e.g. NEEAP 2017), but citizen movements focusing explicitly on energy efficiency have only recently emerged, since energy has been seen more as an expert domain. Residents’ associations have shown some activism around particular solutions and technologies (Heiskanen et al. 2011), often gaining momentum from municipal-level climate action (Heiskanen et al. 2015). Another example of recent citizen activism are online discussion forums, for example a vibrant and popular discussion forum on heat pumps (Hyysalo et al. 2013).

Trends in National Household Energy Campaigns in Finland

Energy saving was heavily emphasized during the oil crises, with forceful advice campaigns and restrictions on e.g. indoor temperatures. As oil prices and overall oil dependency declined, the tone of national energy campaigns shifted to technological innovation and energy efficiency, emphasizing that energy can be saved without loss of comfort.

Finnish national energy campaigns are mainly organized by Motiva, a state-owned company promoting energy efficiency, renewables and materials efficiency. Campaigns have not been a strong focus in recent years, but rather the provision of local targeted practical advice and engagement. This advice focuses on sensible use of energy, i.e. auditing, metering, training, automation, adjusting controls, refurbishment and renewable energy—and, most recently, demand response. Energy Saving Week is one of the nationwide campaigns for homes and workplaces. In addition to Motiva, energy companies also organize campaigns, such as the Energy Family competition by Vattenfall. The Finnish Environment Institute, coordinator of a large carbon neutral municipalities programme, has also organized various campaigns such as joint purchasing of solar panels.

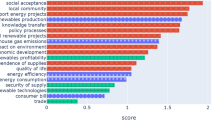

Older SECIs are more focused on technology or individual behaviour change, whereas newer ones focus more on everyday practices and complex interactions between households and systems of provision (Table 12.1). There is a development towards living lab types of approaches, i.e. testing technologies in real-life contexts by engaging citizens in experimentation towards more sustainable lifestyles (Laakso et al. 2017). Moreover, there is a tendency towards integrating energy projects in broader sustainability, liveability and innovation contexts. Many of the newer SECIs still focus on technology, but with the engagement of users, their everyday practices and sometimes even addressing the complex interactions between technologies, hence they are categorized as ‘changes in complex interactions’ and ‘changes in everyday life situations’.

Case Study: Smart Kalasatama

Energy saving is becoming part of a broader tendency in urban planning to promote sustainable lifestyles. The emerging activism by cities in energy and climate is reflected in the Smart Kalasatama case. In order to boost new sustainable urban solutions, the Helsinki City Council decided in 2013 to make one of the new construction sites, the Kalasatama harbor area, a model district of smart city development. By 2030 the area will house about 25,000 residents and offer jobs for 8000 people. The process was initiated by a consortium including the local energy company Helen and other large companies to develop new ‘smart grid’ business. Later, the City of Helsinki placed Forum Virum Helsinki, an innovation intermediary, in charge of the project and Kalasatama was turned into ‘smart city’ area with more diverse aims (Matschoss and Heiskanen 2017, 2018). The aim is also to create a city district co-designed with citizens with the slogan ‘to save one hour of residents’ time per day’. The idea is that Kalasatama is a real-life testbed for new services to be scaled up elsewhere. This is done by providing a platform to co-create smart urban infrastructures and services.

Smart Kalasatama is based on the utilization of different technologies and solutions that all use ICT and open data. Several hundred participants—large and small companies, research, public sector, and citizens—are already involved in developing Kalasatama as a smart district. Helen, together with partner organizations, develops smart grid technologies and services such as an electric car network and battery energy storage. The focus is on experimenting with new solutions at varying scales in real life with residents (Mustonen et al. 2017). The Developers’ Club gathers city administration, resident associations and businesses in the area together four times a year to discuss the development of Kalasatama. This way of working represents a novel way to cooperate at the city district level in Finland.

The Smart Kalasatama case shows how energy considerations are increasingly embedded in wider urban planning targets. And on the other hand, urban planning—at its best—is not seen merely as physical infrastructure planning. It is also about a redistribution of power, where conventional ways of infrastructure development are challenged, new networks among diverse players are forged, and new solutions are sought for via experimentation. On the other hand, in such a diverse ‘smart city’ context, energy and resource conservation may have to compete with other agendas, such as the development of new technology and commercial services. In this sense, Smart Kalasatama is a typical case of such developments, with the same strengths and weaknesses. For example, there might be a need for more assessment of whether ‘smart’ solutions—or new technical solutions in general—deliver the promised environmental benefits, as well as the issue of the extent to which they are scalable (Heiskanen et al. 2017).

An important policy implication from the Finnish cases in general, and the Smart Kalasatama case as an illustration, is that local governments are close to citizens and can influence many of the conditions for sustainable consumption and quality of life. However, local governments might lack the resources, expertise and also the power to innovate, to evaluate projects, and in particular, to scale up innovative practices. Because of this, central governments and the EU might offer more funding for such innovative projects, but also require more and better evaluation and diffusion.

References

Annala, S., Lukkarinen, J., Primmer, E., Honkapuro, S., Ollikka, K., Sunila, K., et al. (2018). Regulation as an enabler of demand response in electricity markets and power systems. Journal of Cleaner Production, 195, 1139–1148.

Apajalahti, E.-L. (2018). Large energy companies in transition—From gatekeepers to bridge builders. Aalto University publication series Doctoral Dissertations, 112/2018.

Haukkala, T. (2018). A struggle for change—The formation of a green-transition advocacy coalition in Finland. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 27, 146–156.

Heiskanen, E., Hyvönen, K., Laakso, S., Laitila, P., Matschoss, K., & Mikkonen, I. (2017). Adoption and use of low-carbon technologies: Lessons from 100 Finnish pilot studies, field experiments and demonstrations. Sustainability, 9(5), 847.

Heiskanen, E., Jalas, M., Rinkinen, J., & Tainio, P. (2015). The local community as a “low-carbon lab”: Promises and perils. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 14, 149–164.

Heiskanen, E., Lovio, R., & Jalas, M. (2011). Path creation for sustainable consumption: Promoting alternative heating systems in Finland. Journal of Cleaner Production, 19(16), 1892–1900.

Hyysalo, S., Juntunen, J. K., & Freeman, S. (2013). Internet forums and the rise of the inventive energy user. Science & Technology Studies, 26(1), 25–51.

Järventausta, P., Repo, S., Trygg, P., Rautiainen, A., Mutanen, A., Lummi, K., et al. (2015). Kysynnän jousto - Suomeen soveltuvat käytännön ratkaisut ja vaikutukset verkkoyhtiöille [Demand response—Practical solutions applicable to Finland and their impacts on distribution network providers]: Loppuraportti. Tampere: Tampereen teknilllinen yliopisto.

Karhunmaa, K. (2018). Attaining carbon neutrality in Finnish parliamentary and city council debates. Futures (in Press, Correct Proof). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.10.009.

Karjalainen, S. (2009). Thermal comfort and use of thermostats in Finnish homes and offices. Building and Environment, 44(6), 1237–1245.

Laakso, S., Berg, A., & Annala, M. (2017). Dynamics of experimental governance: A meta-study of functions and uses of climate governance experiments. Journal of Cleaner Production, 169, 8–16.

Matschoss, K., & Heiskanen, E. (2017). Making it experimental in several ways: The work of intermediaries in raising the ambition level in local climate initiatives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 169, 85–93.

Matschoss, K., & Heiskanen, E. (2018). Innovation intermediary challenging the energy incumbent: Enactment of local socio-technical transition pathways by destabilisation of regime rules. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 30(12), 1455–1469.

Matschoss, K., Heiskanen, E., Atanasiu, B., & Kranzl, L. (2013). Energy renovations of EU multifamily buildings: Do current policies target the real problems. Rethink, renew, restart. In Proceedings of the eceee 2013 Summer Study (pp. 1485–1496). Eceee.

Mickwitz, P., Hildén, M., Seppälä, J., & Melanen, M. (2011). Sustainability through system transformation: lessons from Finnish efforts. Journal of Cleaner Production, 19(16), 1779–1787.

MoEE. (2017). Government report on the National Energy and Climate Strategy for 2030. Publications of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment 4/2017. Online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-327-199-9.

Mustonen, V., Mazur, C., Mattila, M., Hubmann, G., Huuska, P., Jarkko, M., et al. (2017). Deliverable Proof—Reports resulting from the finalisation of a project task, work package, project stage, project as a whole—EIT-BP16. Online: http://fiksukalasatama.fi/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Helsinki-District-Challenge-1_-1.pdf.

NEEAP. (2017). Finland’s National Energy Efficiency Action Plan NEEAP-4. Report to the European Commission pursuant to Article 24(2) of the Energy Efficiency Directive (2012/27/EU). Online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/fi_neeap_2017_en.pdf.

Rinne, S., Auvinen, K., Reda, F., Ruggiero, S., & Temmes, A. (2018, November 28). Clean district heating—How can it work? (Smart Energy Transition Discussion Paper). Online: http://www.smartenergytransition.fi/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Clean-DHC-discussion-paper_SET_2018.pdf.

Runsten, S., Berninger, K. Heljo, J., Sorvali, J., Kasanen, P., Vihola, J., et al. (2015). Pienituloisen omistusasujan energiaköyhyys [Energy poverty among low-income detached house dwellers]. Ympäristöministeriön raportteja 6/2015. Helsinki: Ministry of Environment.

Statistics Finland. (2018a). Appendix table 1. Energy consumption in households 2010–2017, GWh. Online: https://www.stat.fi/til/asen/2017/asen_2017_2018-11-22_tau_001_en.html.

Statistics Finland. (2018b). Final energy consumption by sector by year and sector. Online: http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/en/StatFin/StatFin__ene__ehk/statfin_ehk_pxt_010.px/table/tableViewLayout2/?rxid=cfb16ff0-c8b9-4629-b0f3-04af3d02a009.

Statistics Finland. (2018c). Use of renewable energy continued growing in 2017. Online: https://www.stat.fi/til/ehk/2017/04/ehk_2017_04_2018-03-28_tie_001_en.html.

Statistics Finland. (2019). Buildings by area, year of construction, information and intended use of building. Online: http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/en/StatFin/StatFin__asu__rakke/statfin_rakke_pxt_116g.px/table/tableViewLayout2/?rxid=74aac6df-fd8a-48da-86d6-ed04e7fbc49f.

SULPU. (2019, January 15). Lämpöpumppumyynti ponnahti 22% - Investoinnit yli puoli miljardia [Heat pump sales increased by 22%—Investments more than half a billion]. News release by SULPU, Finnish Heat Pump Association. Online: https://www.sulpu.fi/uutiset/-/asset_publisher/WD1ExS3CMra3/content/lampopumppumyynti-ponnahti-22-investoinnit-yli-puoli-miljardia?.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Heiskanen, E., Laakso, S., Matschoss, K. (2019). Finnish Energy Policy in Transition. In: Fahy, F., Goggins, G., Jensen, C. (eds) Energy Demand Challenges in Europe. Palgrave Pivot, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20339-9_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20339-9_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Pivot, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-20338-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-20339-9

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)