Abstract

The present study examines teachers’ professional identity, focusing on the development of a measurement instrument. The final scale resulted in two consecutive steps. First, we analyzed the responses of 104 primary teachers on a pilot scale with 73 items. This analysis resulted in a scale with 58 items, which was administered to 315 primary teachers, leading to the final scale comprised of 48 items in seven dimensions. Through further analysis, we found that specific teacher characteristics appear to be related to teachers’ professional identity. Hierarchical cluster analysis indicated that there exist three groups of teachers with different identity characteristics—characterized as teachers with positive professional identity, teachers with negative professional identity, and uncommitted teachers. Semi-structured interviews revealed significant differences between the teachers of the three groups regarding the majority of the seven dimensions. In conclusion, we propose confirmation of the scale in different cultures and further examination of the characteristics of the three groups of teachers, as a mean to enhance pre-and-in service education programs. We also propose the development of professional identity scales for mathematics teachers and teachers specialized in other school subjects.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

During the past decades, the concept of teachers’ professional identity (TPI) has attracted widespread attention and emerged as an important area of research (Akkerman & Meijer, 2011; Beauchamp & Thomas, 2009). Quite a few existing studies across countries have considered the TPI as a key factor in understanding teachers’ professional lives, career decision making, motivation, effectiveness, retention, professional development and their attitude toward educational change (Beijaard, Meijer, & Verloop, 2004; Day, Elliot, & Kington, 2005; Lasky, 2005). However, despite the growing body of literature on TPI, Beijaard et al. (2004) in their review of research, maintain that the concept of TPI continues to appear with different meanings and definitions. In particular, in the domain of teaching and teacher education, researchers who study TPI differ in terms of how they define, view and study this concept. They usually agree though, on the fact that professional identity (PI) is at the same time a product and a process (Olsen, 2010). The term product draws upon psychological theory and can be understood as the meanings that people attach to themselves as a result of the interaction among elements of the teacher as a person and as a professional at a given moment. The term process refers to changes in that perception because of influences and meanings that is attributed by “others” through social practice.

Recently, the concept of TPI has come to the foreground in the field of mathematics education, examining how both specialized and non-specialist mathematics teachers (such as primary school teachers) understand themselves in the context of mathematics. The difference is that primary teachers who teach mathematics are generalists, meaning that they do not personally identify to the subject and hence they do not consider themselves as mathematics teachers. On the other hand, the challenge for the mathematics teachers is even more complex, since they have to develop both mathematics and teaching identities (Adler, Ball, Krainer, Lin, & Jowotna, 2005).

Considering the difference between primary school teachers (generalist—teaching several subjects) and secondary school teachers (specialists in specific school subjects), in our study we have only covered the first group of teachers. It remains to develop specific scales appropriate for teachers specialised in different school subjects, e.g., mathematics, science, etc. The developed scale may provide the basis for this task.

2 Theoretical Background and Aims of the Study

The concept of identity has been conceptualized and used by scholars and researchers from three different perspectives: the psychological, the sociological, and the postmodern. However, recent conceptualizations of teacher identity seem to reflect rather the sociological and the postmodern views. The sociological approach emphasizes the sociological processes as primary influences on TPI, while the postmodern approach stresses the notion of multiple identities, which are continuously reconstructed and connected to people performances. In a more balanced approach, the theory of dialogical self (Hermans, 1996) conceives TPI “as both unitary and multiple, both continuous and discontinuous, and both individual and social” (Akkerman & Meijer, 2011, p. 308). This dialogical position between individual and social dimensions is crucial for the formation of TPI since no professional identity exists without both dimensions (Krzywacki & Hannula, 2010).

Although TPI is influenced by social relationships and the context, as sociological approach emphasizes, we argue that the main contribution to the process of its construction and reconstruction comes from the part of the individual, through the processes of interpretation, self-reflection, and agency. If one claims that teachers’ identity is socially determined, it is hard to understand how they can still act as ‘unique’ individuals and professionals, showing agency as they move from various contexts. Furthermore, even though teachers may have a number of sub-identities connected to specific situations, as the postmodern approach suggest, an entirely decentred characterization of TPI raises the question of how a teacher can maintain any sense of professional self through time or how he can be recognized as the same person as he was yesterday. Therefore, a completely decentralized idea of identity is not possible in order to understand how TPI evolves and how individuals are able to maintain a sense of self through time (Akkerman & Meijer, 2011). Even though we acknowledge the dynamic nature of TPI in which both the individual and the social dimensions are key elements, we consider that TPI draws upon psychological theory, as the process centered on the individual and his/her self-reflections in the mirror of human nature.

Several scholars have found that TPI is related to images of self (Knowles, 1992; Nias, 1989). In teaching, one’s conception of himself/herself as a person is interwoven with how he/she acts as a professional. The person cannot be separated from the profession; “it seems unlikely that the core of the personal will not impact the core of the professional” (Loughran, 2006, p. 112). In the same line, Nias (1989) has concluded that TPI is closely bound with personal and professional values and is only adjusted according to circumstances. She considers TPI as part of a deeply protected core of self-defining beliefs and values, which gradually become part of the individual’s self; she further argues that most teachers have an over-riding concern that is the preservation of a stable sense of their PI. Furthermore, Ball (1972) separates the substantial (stable) from the occasional identity, which is the presentation of self that varies according to specific situations for assessment. The substantial identity is the basic presentation of a person’s general perception of himself/herself. According to Gee (1990), postmodern notions are not to deny that each person has a “core identity” that holds more uniformly for ourselves and others across contexts. We argue that the core (or substantial) identity arises from the natural desire of the individual to maintain a consistent and coherent sense of self that separates and stigmatizes each person. Consequently, a general definition that may fit our view is that: “TPI is the perception that teachers have of themselves at a present time” or the answer to the question: “Who am I as a teacher at this moment?” (Beijaard et al., 2004). This present image consists of a conscious understanding of his/her own professional self.

2.1 Factors of the TPI

The concept TPI includes strong affective factors such as beliefs, emotions, orientations, motivations, and attitudes (Frade & Gómez-Chacón, 2009). Some major psychological concepts have emerged as factors or dimensions of TPI from past research. For example, Kelchtermans (2009) lists the following five interrelated factors of TPI: self-image, self-esteem, job motivation, task perception, and future perspective. For Day (2002), TPI includes job satisfaction, professional commitment, self-efficacy, and work motivation.

In conclusion, we have been able to identify the following concepts, some way or another, related to TPI: self-efficacy, self-esteem, professional commitment, job satisfaction, task orientation, work motivation, and future perspective. These concepts operate as a personal lens through which teachers reflect on their practice and generally consider themselves at work. Even though these concepts may constantly interact, separating them would provide a deeper comprehension of teachers’ self-understanding and feelings about their work (van Veen & Sleegers, 2009).

Several researchers have recently used these concepts as dimensions of professional identity (Canrinus, Helms-Lorenz, Beijaard, Buitink, & Hofman, 2012; Lamote & Engels, 2010). In this line, the present study attempts to identify these concepts in order to develop a valid and reliable instrument for measuring TPI. A brief description of these concepts follows.

Self-esteem concerns a general descriptive assessment of the teacher’s performance in relation to his work; it also refers to the evaluation of a teacher on the basis of expectations compared with the expectations of others (Kelchtermans, 1993). It is an indication of the relationship between the actual self-image and the ideal self-image (Kelchtermans & Vandenberghe, 1994). A highly important source for self-esteem is the feedback from significant “others” which is continuously filtered and interpreted by the individual. For most teachers, the students are the most important source of feedback, as it is the ultimate reason for their existence. Students have the ability to empower or destroy the self-esteem of teachers since the latter spend most of their working lives with students and the interactions with them define their professional reality (Nias, 1989). The positive self-esteem, however, is fragile to variations in time and must be constantly supported. Self-esteem is positively related with job satisfaction (Bullough, 2009).

Self-efficacy refers to one’s ability to succeed in a certain task (Bandura, 1993) and comprises an important moving factor. In education, efficacy beliefs are defined as beliefs that one has in his ability to succeed in a particular teaching task (Charalambous, Philippou, & Kyriakides, 2008). Self-efficacy is positively related to motivation (Bandura, 1993) and especially to the intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). A significant positive correlation has been also found between self-efficacy and professional commitment, and between self-efficacy and job satisfaction (Caprara, Barbaranelli, Steca, & Malone, 2006; Chan, Lau, Nie, Lim, & Hogan, 2008). Self-efficacy is a future-oriented assessment regarding perceptions of competence and is affected by previous successful experiences, indirect experiences, persuasion by others and emotional feedback (Hoy & Spero, 2005). Teachers’ self-efficacy plays an important role in students’ learning outcomes since the quality of teaching and effective classroom management is directly linked with the confidence that teachers have in their abilities, which in turn affect their enthusiasm and professional commitment (Bandura, 1993).

Professional commitment refers to the psychological ties of a person with his job (Lee, Carswell, & Allen, 2000). Tyree (1996) refers to four dimensions of professional commitment: commitment to care, commitment as a professional ability, commitment as identity, and commitment as a career. As Nias (1989) mentions, after 20 years of relevant research, the word “commitment” appeared in almost every interview. It was a term used to distinguish those teachers who feel care and take their profession seriously, from those who measure their own interests first. Furthermore, when teachers develop professional satisfaction from their commitment, they derive a sense of pride for their professionalism.

Professional commitment can be influenced by several factors such as student behavior, administrative support, parental demands and educational reforms (Day, 2002; Tsui & Cheng, 1999). Professional commitment can be understood as an integral phenomenon, the center of which is a set of basic, relatively permanent values based on personal beliefs, images of self and a sense of the role which may be challenged by significant changes (Day et al., 2005). Furthermore, it was found that commitment has a considerable influence on students’ achievement and attitudes (Day et al., 2005; Tsui & Cheng, 1999). Finally, professional commitment is positively related with self-efficacy and job satisfaction (Bogler & Somech, 2004).

Job satisfaction refers to the positive or negative judgments people make about the value of their work (Weiss, 2002). Job satisfaction of a teacher can be defined as the emotional response to his work and his teaching role (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2010). Many studies have attempted to identify the sources of satisfaction of teachers in both primary and secondary education (e.g., Dinham & Scott, 1998; Evans, 2001) and several factors were found to contribute to teachers’ job satisfaction: relationships with children, the mental challenge of teaching, autonomy and independence, opportunities for testing new ideas, participation in decision making and reform efforts, social relations with colleagues and opportunities for professional development (Latham, 1998; Zigarelli, 1996). In contrast, sources of dissatisfaction for teachers include monotony of everyday life, lack of motivation, indiscipline on the part of students, lack of support and appreciation from colleagues and manager, excessive workout, low salary and the negative treatment from society (Nias, 1989; Zembylas & Papanastasiou, 2006). These factors cause various negative feelings like frustration and vulnerability to teachers. Job satisfaction was found to be related to professional commitment and change of teachers motives (Canrinus et al., 2012).

Work motivation comprises of the forces that push a person to spent time, energy and resources to initiate behaviors related to his work (Latham & Pinder, 2005). Motives determine the form, direction, intensity and duration of these behaviors. The reasons that teachers choose the teaching profession can be divided into altruistic, intrinsic, and extrinsic (Kyriacou & Coulthard, 2000). Altruistic motivation includes teaching as a socially important job, intrinsic motivation includes personal satisfaction and enjoyment from work, while extrinsic motivation is related to factors such as social awareness, job security and high salaries.

Work motivation influence teachers’ decisions to stay or to abandon their career and is considered one of the most important aspects of their PI (Kelchtermans & Vandenberghe, 1994). Huberman, Grounauer, and Marti (1993) argue that the motives that push teachers to choose teaching profession as a career are often contradictory since usually there are numerous contextual factors that play an important role in their decision. They argue that in addition to considering the initial motives that lead young persons to become teachers, it is important to document the evolution of motivation during their educational career as well, in order to understand how their motives evolve over time. In this study, the reasons for teachers choosing the profession are examined in relation to the current motives.

Task orientation refers to the task that one is expected to pursue as a good teacher, regarding the aims of education, the teaching process, and the teacher—student relations (Billig et al., 1988). It is mainly related to the cognitive aspect of TPI, as it refers to the perceptions of teachers in relation to their work and the key tasks that need to perform (Kelchtermans, 2005).

Task orientation includes deeply ingrained beliefs about the purpose of education and teaching methods (Lamote & Engels, 2010) that guide teachers’ professional activities and behaviors (Akkerman & Meijer, 2011). These beliefs can be viewed as a lens, through which teachers perceive and filter external information and play an important role in the development of their PI (Kagan, 1992). There are three dimensions of task orientation, (a) relationship between teacher and students, (b) purposes of education and (c) didactic approach (Denessen, 1999). For each of these dimensions, teachers may have either a student-centred approach focusing on the process or a teacher-centred approach focusing on the content. In the case of student-centred approach, teachers emphasize the active involvement of the students in the moral purposes of education and the construction of knowledge, while more teacher-centred approach gives more emphasis on classroom discipline, the students’ qualified equipment and the development of knowledge and skills. However, teachers may have both student-centred and teacher-centred perceptions at the same time (Van Driel, Bulte, & Verloop, 2005).

Future perspective concerns how a teacher foresees himself in the coming years and how he/she feels about it (Keltchermans, 2009). This dimension has been ignored in the literature since there are few studies that have linked this concept to other aspects of TPI. The dreams that people have about the kind of teachers they want to become and whether they can be fulfilled, influence their decisions, their feelings and their behavior. Therefore, apart from the significant experiences of the past, self-understanding of the individual is also affected by the future expectations as well (Keltchermans, 2009).

2.2 Aims of the Study

The above concepts have been examined separately or in groups, but rarely altogether as dimensions of a unitary construct (e.g., Canrinus et al., 2012). Although research on TPI in recent years has been increased, the interest has mainly been focused on student-teachers and the effect on their identity development during the transition to school (e.g., Timostsuk & Ugaste, 2010), or the impact of innovations when teachers facing educational reforms (e.g., Lasky, 2005). At the same time, most researchers rely on biographical and interpretative research, which have as a basic methodological tool the interviews (e.g., Van Veen & Sleegers, 2009).

The most frequently mentioned TPI scale (Canrinus et al., 2012) includes only some of the above concepts. Hence, the need for a reliable instrument based on the maximum possible dimensions, a TPI scale that reflects the overall picture that teachers have about themselves as professionals. Another area in which research is so far missing from the literature is a possible connection between TPI and teachers’ personal characteristics, namely: gender, teaching experience, professional post, and academic qualifications. It will also be interesting to look for teachers groups with a different PI profile, as teachers with similar PI may behave analogously in the class. Apart from the development of the scale and the analysis of quantitative data, semi-structured interviews were used to a deeper understanding of TPI.

Therefore, the aims of this study were:

-

1.

To develop a valid and reliable instrument for measuring primary teachers PI,

-

2.

To search for possible differences between TPI according to their, personal characteristics and,

-

3.

To locate possible groups of teachers with different PI profile.

In order to fulfill its aims, this study employed a mixed-method design which used both the qualitative and quantitative approaches. We utilized both approaches in a way that has “complementary” strengths (Johnson & Turner, 2003). According to Greene, Caracelli, and Graham (1989), different types of data can be used in order to seek elaboration, enhancement, and clarification. Furthermore, two different types of data can provide validity evidence by seeking corroboration and integrity of findings, establishing triangulation of the study. This study employed quantitative surveys to develop the scale, used the scale to examine how teachers differentiate on TPI according to their individual characteristics and to investigate whether different clusters of teachers exist on the basis of the scale factors. Then, qualitative semi-structured interviews followed to illustrate and elaborate on these differences in more depth, since the use of qualitative data “sheds light” to the quantitative findings, “putting flesh on the bones of dry quantitative findings” (Bryman, 2006, p. 106). Specifically, semi-structured interviews were conducted to interpret and to understand in more depth the differences between teachers.

3 The Development of the TPI Scale

For the development and validation of the scale measuring TPI, two consecutive phases were completed, the pilot study and the final study.

3.1 The Pilot Study

For each of the above mentioned concepts of the TPI for which related measurement scales were identified, we have selected and formed items for the trial scale; for the remaining concepts we proposed items, on the basis of the existing literature. Specifically, the initial trial scale consisted of 73 items, covering all possible factors as follows.

Self-esteem: We have proposed 5 items. Sample item: “I feel that my students are proud to have me as their teacher”. Self-efficacy: We have adjusted 11 items from the scale “Teachers’ sense of efficacy scale” (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001) which comprise three dimensions: student motivation, teaching strategies, and discipline in the class. Sample item: “I can explain even the most difficult concepts to my students in order to understand them”. Professional commitment: We have adjusted 9 items from the scale “Commitment in Teaching” (Van Huizen, 2000). Sample item: “As a teacher, I believe I have a key role in society”. Job satisfaction: We have proposed 10 items. Sample item: “I am thrilled by my profession”. Work motivation: We have proposed 9 items. Sample item: “I chose to become a teacher because it is the profession I have always dreamed of”. Task orientation: We have proposed 22 items. Sample item: “Students learn best when knowledge is transferred from teacher”. Future perspective: We have proposed 7 items. Sample item: “I expect in the future that I will have the professional development that I deserve”.

These 73 items comprise the initial trial Likert-type scale of six alternatives (1-absolutely disagree, 6-fully agree), which was administered to 104 primary teachers in public schools across Cyprus. At the same time, the teachers were asked to state their demographic data: gender, years of service, qualifications, and educational post. Two open questions were added to the motivation factor, asking the teachers for their reason to become and their reason to remain a teacher. Out of the 104 participants, 85 were females and 19 were males. The average number of years of teaching was 21.2.

Exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation and principle component were carried out of the responses to these 73 items. Initially, the 73 items were extracted into 9 factors that had eigenvalues greater than 1.25 and explaining the 56.75% of the total variation. Since only three items were found to load on the factors 7 and 8, these items were omitted and the factor analysis was repeated with the other 70 items, using the same criteria. The second exploratory factor analysis was extracted into 7 factors. Job satisfaction did not appear as a factor by itself as the relevant items loaded mainly on professional commitment. This result can be justified because the emotional aspect of job satisfaction is also contained as an aspect of professional commitment. Furthermore, the items classified as self-esteem loaded mainly on self-efficacy. Again, this result can be attributed to the fact that these 2 concepts have high conceptual relevance. Consequently, these two factors were excluded from further analyses. At the same time, task orientation was found to be separated into constructivist and traditional perceptions, while motivation was split into intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. After removing the 12 items of self-esteem and job satisfaction, the scale remained with 58 items.

3.2 The Development of the Final Scale

The scale of 58 items found above was administered to a stratified sample of 315 primary teachers, 40 males (12.69%) and 275 females (87.31%), 240 were ordinary teachers, 15 were school principals, 47 were assistant school principals, and 13 substitutes; 64 had 0–10 years of service, 149 had 10–20 years of service and 102 over 20 years of service; 17 had a Ph.D., 174 a Master degree, and 124 only a bachelor degree.

The responses of this sample were analyzed using descriptive and inductive statistics of the SPSS statistical package. As regards the factors of TPI, a number of exploratory factor analyses were conducted in order to check the pilot scale and to confirm the theoretical differentiation factors constituting TPI, as recorded in the literature. Since the constructed items had not yet been used together in any previous research, we conducted a principal component analysis (PCA) in order to reduce the confounding of constructs and purify the latent variables. In the main study, an exploratory factor analysis was followed by a confirmatory factor analysis in order to check the proposed measurement scale. The reliability of the factors was tested using the Cronbach’s alpha index.

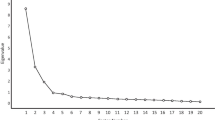

The first exploratory factor analysis led to 8 factors with eigenvalues >1.25, but the scree plot indicated that the grouping of the path appeared after the seventh factor. At the same time factor loading and variance led to disregarding 6 items with variance <.40 and 4 items which failed to load to the appropriate factor. A second exploratory factor analysis of the remaining 48 items with the same criteria led to 7 factors that explained 50.90% of the total variance. To further confirm the factor analysis of the 48 items, a confirmatory factor analysis using varimax rotation and maximum likelihood was applied, revealing the same factor analysis structure (χ2 = 1360.61, degrees of freedom = 813, p = 0.001). The remained factors, the number of items in each factor, the variance explained by each factor, and an indicative item per factor with its loading, respectively follow:

Self-efficacy (11 items, explained 13.82% of the total variance): “I can motivate students with a low interest in the class, as well” (load 0.76).

Constructivist perceptions (11 items, explained 7.73%): “Students learn better when they control, program and direct the learning process by themselves” (load 0.65).

Intrinsic motivation (4 items, explained 6.52%): “I chose to become a teacher because I love working with children” (load 0.77).

Extrinsic motivation (5 items, explained 6.23%): “I chose to become a teacher because I would have good working conditions, such as the working hours and vacations” (load 0.80).

Traditional perceptions (8 items, explained 6.14%). “Students learn better when the teaching emphasizes the content (what we learn)” (load 0.65).

Future perspective (4 items, explained 5.53% of the variance): “I worry about my future as a teacher” (load 0.71). * reverse coding.

Professional commitment (5 items, 5.16%): “If I could find an equally good job, I would give up the teaching profession” (load 0.70). ** reverse coding.

Table 18.1 shows the mean, the standard deviation and the reliability for each factor. The Cronbach’s alpha obviously present from moderate to high internal reliability for all factors (α = .71–.92). The items of self-efficacy show the highest reliability (α = .92), while the items of future perspective show the lowest internal reliability (α = .71). The latest can partly be attributed to the fact that this factor comprises of only 4 items.

The participant teachers seem to have rather high self-efficacy (Μ = 4.33), rather low motivation, higher intrinsic than extrinsic motivation (Μ = 3.89, against Μ = 2.86), very low job expectations (Μ = 2.05), and quite high, constructivist compared to traditional perceptions (Μ = 4.52, against Μ = 3.14).

The Pearson correlation coefficients for the seven factors were quite reasonable. Self-efficacy was positively correlated with all the other factors (higher with constructivist perceptions, r = .54, p < .01), except with the external motivation. Constructivist perceptions were positively correlated with all the other factors except with external motivation; internal motivation was positively correlated with all the other factors except with external motivation, which in turn was correlated with traditional perceptions (r = .25, p < .01), future perspective and negatively with professional commitment (r = −.11, p < .05).

4 Teacher Personal Characteristics and PI

Regression analysis was used to examine whether the PI is associated with teachers’ personal characteristics (the second aim of the study). The search concerned possible differences between teachers’ gender, teaching experience (three groups, GA: 1–10 years of service, GB: 11–20, and GC: 21–33 years of service), administrative post, and academic qualifications, regarding their TPI. The ANOVA was used to examine whether statistically significant differences exist, followed by post hoc tests using the Bonferroni correction for significance. The findings are summarized as follows.

-

a.

Male teachers were found to significantly exceed female in external motivation (F(1,310) = 4.60, p < .05); the average of male teachers in this PI factor was Μ = 3.17 (SD = 1.01), against M = 2.80 (SD = 1.02) for female teachers.

-

b.

Statistically significant difference was found in intrinsic motivation, among the three groups of teachers by the length of service (F(3,310) = 3.61, p < .05). The difference existed only between the GA teachers (M = 4.24, SD = 1.08) and the GC teachers (M = 3.64, SD = 1.07). In other words, as the teacher’s service time increases, their internal motives tend to decline. This can be attributed to the possible gradual reduction of enthusiasm of teachers and to the burnout that may occur over time.

-

c.

Statistically significant difference regarding future perspective was found according to administrative post (F(3,310) = 4.30, p < .05). The school principals’ mean (M = 2.60, SD = .90) was significantly higher than that of the teachers’ mean (M = 2.01, SD = .75). This can be attributed to the negative career prospects of the teachers due to the social and economic crisis (see also the interviews). There were no statistically significant differences between principals and assistant principals and neither among ordinary teachers and assistant principals (p > .05).

-

d.

Statistically significant difference was found among teachers with, and teachers without graduate qualifications, regarding constructivist perceptions (F(2,310) = 5.58, p < .05) and traditional perceptions (F(2,310) = 6.89, p < .05). Specifically, the average of teachers with only a bachelor degree in constructivist perceptions was lower (Μ = 4.41, SD = .57) than the average of teachers with a Master’s (Μ = 4.59, SD = .58) and the teachers with a Ph.D. (Μ = 4.82, SD = .54), while the average responses of teachers with only a bachelor’s degree in traditional perceptions was higher (Μ = 3.26, SD = .55) than the average of teachers with a Master’s (Μ = 3.07, SD = .62) and the teachers with a Ph.D. (Μ = 2.73, SD = .61). There was no difference between teachers with a Master’s and teachers with a Ph.D. regarding the constructivist or the traditional perceptions (p > .05). Consequently, it seems that teachers with advanced graduate studies hold more constructivist perceptions and simultaneously less traditional perceptions. Such a conclusion is assessed as very important since it connects the level of study with the kind of pedagogical beliefs of teachers.

5 Groups of Teachers with Different PI Profile

Hierarchical cluster analysis of the teachers’ responses to the final scale was performed (Ward method) to search for possible groups of teachers with different PI. The dendrogram analysis resulted in three clusters of teachers and the non-hierarchical cluster analysis (K-means) examined these three groups in terms of the constructs that constitute TPI. Finally, we conducted ANOVA to detect any statistically significant differences between the three clusters.

In the first cluster there were classified 121 teachers (39%), in the second 106 (34%), and in the third 86 teachers (27%). The first group with the lowest mean in all seven factors was characterized, as teachers with negative PI (group I). The second group with the higher mean in self-efficacy, constructivist perceptions, internal motives, future perspective and professional commitment, with major differences from the other two groups in the latter two factors, was characterized, as teachers with positive PI (group II). The mean of the third group exceeded the means of the other two groups in external motives and in traditional perceptions while having the lowest mean in professional commitment the same time. These teachers were called uncommitted teachers (group III). Figure 18.1 presents the mean of each factor for each professional profile.

According to Akkerman and Meijer (2011), characterization of teachers with a label may prove problematic, as it may imply stability of TPI. The present study shares the above concern and therefore, stresses that the given labels serve only descriptive purposes. There is no intention, by any means, to imply uniqueness or stagnation of TPI or that the teachers who currently belong to any group cannot be moved to another. The PI which the teachers appear to have through their responses to a questionnaire is the basic perception of themselves at a present time, through their effort to maintain a consistent and coherent sense of self.

The ANOVA revealed significant differences among the above three groups in terms of the seven factors. Specifically, in terms of self-efficacy (F(2,310) = 195.22, p < .05), constructivist perceptions (F(2,310) = 106.87, p < .05), internal motivation (F(2,310) = 43.63, p < .05), future perspective (F(2,310) = 12.68, p < .05), external motivation (F(2,310) = 24.84, p < .05), traditional perceptions (F(2,310) = 31.54, p < .05) and in terms of professional commitment (F(2,310) = 108.68, p < .05). Post Hoc analyses using the Bonferroni correction for significance, indicated that the only non-statistical significant differences were: (a) among the teachers with positive PI and the uncommitted teachers in terms of self-efficacy (p = .54), (b) among the teachers with negative PI and the uncommitted teachers in terms of future perspective (p = 1.0) and (c) among the teachers with negative PI and the teachers with positive PI in terms of external motivation (p = 1.0).

Then, a chi-square test of independence was performed to examine whether the three clusters of teachers differ regarding the personal teachers’ characteristics; gender, teaching experience, administrative post, and academic qualifications. As resulted from the crosstabs analysis, there were no statistically significant differences between the teachers’ professional profile and gender (χ2(2) = 3.960, p = .138), teachers’ experience (χ2(6) = 6.874, p = .333), and administrative post (χ2(6) = 9.948, p = .127). However, there was a statistically significant difference between the observed and expected frequency regarding teachers’ academic qualifications and the teachers’ clusters, (χ2(4) = 22.42, p < .001). The teachers with graduate qualifications, (a Master’s or a Ph.D. degree) were more likely to be classified to the second cluster as committed teachers. A possible reason for this finding can be attributed to the fact that teachers with graduate qualifications hold more constructivist perceptions and simultaneously less traditional perceptions and at the same time may have higher self-efficacy beliefs than their colleagues. This result is quite important, as it connects the level of the academic qualifications with TPI and must be evaluated accordingly by the educational authorities.

6 A Deeper Examination of TPI

For a deeper examination of TPI, we selected 20 primary teachers for semi-structured interviews; 7 from the group I, 7 from group II, and 6 from group III. The criterion for selecting these 20 teachers was the differences in their PI, which emerged from the quantitative analysis. Each interview lasted for about 1 h and was recorded using a digital recorder. The interview featured questions such as: “What do you think is your main task as a teacher?” and “How do you describe your future as a teacher?” The qualitative data were analyzed by inductive analysis and constant comparison methods, using the NVivo software package, to look for common patterns, differences, and substantive themes (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). By comparing the patterns, we can enhance generality of the findings (Miles & Huberman, 1994). In the next paragraphs, we present indicative comments with regard to each of the main TPI factor.

Self-efficacy: Regarding self-efficacy, no significant difference was identified between the 3 groups, as all teachers declared to feel highly efficacious. The main source of such feeling was their relations with students and the comments by parents and colleagues. However, a common theme that differentiated the teachers with negative PI (group I) from the teachers of group II and III was the relationship between self-efficacy and motivation. For some of the group I teachers, self-efficacy and professional development was associated with external motives and the lack of internal motives.

For example, Charis (group I) said: “I feel that I am quite capable, but you know… (3 s pause) I am as capable as I need to be… I have not any motives to become even better… I am talking about promotion. If such motives existed I think I would be even better”. Similarly, Myria (group I) connects her self-efficacy and commitment with the gradual loss of internal motives, which originated from her experience. She said: “The last few years I have lowered my expectations, both my own and for my students… I do not take it personal if some students do not follow… I do my best and that’s it! I used to try to pull the student over with any mean… not anymore… There are no specific incidents that change my point of view; it was brick by brick from my everyday experiences and disappointments that just make me want to be formal or just good, but not great”.

On the other hand teachers from groups II and III approach this issue from a different perspective, as they connect their self-efficacy with their internal motives. For instance, Nicholas (group II) said: “I constantly try to get better because I like the courses I teach… Mathematics and Natural Sciences… and because I owe it to the students I have in front of me… I know it’s difficult times and that probably I will never get a promotion, but I will not punish the students for this”.

The relationship between self-efficacy and motivation that emerged from the interviews analysis has been confirmed in several studies. As Bandura states (1993), the self-efficacy beliefs are positively related to the motivation and particularly with intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Task orientation: The majority of the teachers were found to hold both student-centred and teacher-centred perceptions, emphasizing the ethical and social aims of education or drawing on the need to develop knowledge and skills, respectively. This finding is consistent with other researches which found that teachers may have both student/learning-centred and teacher/content-centred perceptions at the same time (Van Driel et al. 2005). However, their perceptions were somehow in line with their TPI group as there was a different pattern between the teachers of the three groups. The teachers from groups I and III tended to perceive more teacher-centred perceptions than those of group II. For instance, Chryso (group III) defined as her primary aim, “… the transfer of knowledge, followed by the character development”. Chrysanthos (group I) was clear about his preference; He said that the process of knowledge construction is sometimes a waste of time; “If we insist on knowledge discovery, we shall cover half of the curriculum”. Similarly, Kate (group III) said that “students enjoy knowledge discovery but the pressure to cover the subject matter is a trap leading to telling them how to find it”.

On the other hand, the priority of Penelope (group II) was the social aim, “… to develop good citizens”; she said, “I am looking for students with emotional intelligence… not technocrat… the good and credible citizen, in the Greek sense of the terms”. Another teacher, Stelios (group II) said, “I do not give readymade food, I always try to offer students the chance to construct knowledge by themselves, even though I know that some students can hardly make it”.

Work motivation: Several researchers stretch the importance to monitor the development of motives during the career of teachers (Huberman et al., 1993). This perception guided the interview questions in relation to this factor in order to understand the evolution of the original motivation of teachers over time. The analysis of responses to the open question for the reasons that force teachers to remain in the profession revealed that the current motives are the same as the initial motives which led them to choose the profession.

The participants’ comments about the reasons that led them to become teachers differed according to the PI group. The motives of the groups I and III were and remained mainly external. For instance, Olga (group Ι) mentioned, “Vacations, the working hours and the salary; those were the pros then and continue to be”. Helen (group ΙΙΙ) said, “I had no special love for the profession… no, my feelings did not change… to be honest, I do not even love my job”.

On the contrary, most of the group II teachers were internally motivated. For instance, Stella (group ΙΙ) mentioned her love for the children, as she said, “… my passion for helping children to learn what I love, arts. I feel the need to pass on this love to children”. Joanna (group ΙΙ) considered that “…the teaching profession offers the chance to change people and the society. That was my motive… it has now become even stronger”.

Professional commitment: Professional commitment was also found to be related to TPI. When participants were asked about the meaning of “being committed” and to evaluate their commitment, teachers from groups I and III revealed different perceptions from teachers of group II.

For the teachers from groups I and III, the commitment was connected to the time needed for preparation and other factors, such as motivation. John (group I) said, “I don’t think that I am 100% a committed teacher. I try my best in the class but I do not prepare myself properly… except when I expect my inspector to come… I think most teachers do the same”. The civil servant mentality approach of John is obvious. Helen (group ΙΙΙ) said, “During the 22 years of service I have never gone to my class without proper preparation… however, the odds to choose the same profession again is 60% no and 40% yes”. Olga (group I) justified her low commitment due to working conditions, “If I had a music room, well equipped and smaller groups of students, I would have been better”. She complained about underestimating her subject and stated: “If I could turn back the time, I would not have become a teacher”. Some teachers of group I and III seemed to have regretted their choice since their commitment has been “wounded”.

On the other hand, the commitment of the group II teachers was obvious and directed towards the students and to their profession in a broader sense. Anna (group ΙΙ) expressed a high level of devotion, she stated: “I am as committed as I would like the teachers of my kids to be; as I demand from the doctor to be a professional and formal, I feel that I must also be professional”. Stella (group II) expressed her commitment at a different level, as she defended her profession in a broader sense. She stated, “I get angry with those who behave casually because they tarnish the picture of our profession”.

Future perspective: Despite some differences among the groups, it seems that all interviewees do not see any positive future, neither personal nor for the educational system. However, a different pattern among the groups was clear, with regard to reasons for a negative prospect. Teachers of groups I and III connect their future prospects as teachers, almost exclusively with the lack of external motives for professional and economic development. Stylianos (group I) and Vangelis (group III) complained about low promotion prospects and for the reduction of salaries. Stylianos said, “I try to forget all the problems when I am in the class, but I have no motives”. In the same tune, Vangelis said, “Compared to prior conditions, I would have got a promotion in 3–4 years time, while now I have no hope for promotion, even in ten years’ time”. Aphrodite (group III) described the future negatively, though for somewhat different reasons. She was afraid that she won’t be capable of fulfilling her obligations, as she wondered, “I am 46 and I feel already tired, imagine how difficult it would be for me in my remaining 17 years of service”. She also brought up her worries about changes in student’s behavior, as she said, ‘‘the conditions in schools are becoming more and more complicated and we have no reward to try our best”.

On the other hand, teachers of group II expressed their worries about the negative future of the educational system in a broader and “unselfish” sense, as they referred to the dystocia for educational reform and prospects of the teaching profession to attract capable persons. Nina (group ΙΙ) felt that the effort to reform the system was hopeless, as she said, “Α hope… turned to be a conservative process. Moreover, there are no young people entering the profession, the Pedagogical Departments do not attract capable persons anymore”. Anna (group ΙΙ) also referred to the system and claimed: “My problem is with the system… we are in an unspecified process which changes according to the government, with drawbacks”.

To a large extent the analysis of the interviews resulted in conclusions consistent with the quantitative data. Based on the two methodological approaches, it appears that the differences concerning the TPI factors are more pronounced among teachers with different professional profiles than with teachers belonging to the same professional group. However, the interviews have also revealed rather mild differences among teachers of the same group. A more general conclusion resulting from the semi-structured interviews is that all factors are interrelated and constantly interacting with each other. However, the concept that seems to be a key factor defining consciously or unconsciously teachers’ thoughts, emotions, beliefs, and behavior, was work motivation as it was the most frequently mentioned factor. Based on the qualitative data, more attention should be paid to teachers’ motivation during teacher education.

7 Conclusions, Discussion, and Limitations

The aims of this study were to meet three needs which seemed to be missing from the research in teachers’ PI, i.e., to develop a scale measuring TPI that takes into consideration as many factors/concepts as possible, to search for possible differences between TPI according to their personal characteristics, and to search for possible teacher groups with different PI. Apart from the quantitative data analyses, the latter aim was also examined using semi-structured interviews in order to deeper examine how teachers conceptualize themselves at work and locate possible differences among teachers with different PI.

The developed scale consists of five factors, two of them with two dimensions; motivation was split into intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, while task orientation was split into constructivist and traditional perceptions. The other three factors were self-efficacy, professional commitment, and future perspective. The structure of the developed scale remains to be tested for possible confirmation in different samples and in different cultures. Since the developed TPI scale refers to primary teachers who teach many different subjects (generalists), several special scales may be developed measuring the TPI in specific school subjects, e.g., mathematics, science etc. The present scale may provide the basis for such scales.

The differences between male and female teachers can somehow be explained, as well as the differences among teachers with and teachers without graduate qualifications. The relation, however, between teachers’ personal characteristics and their PI needs further examination. Similarly, the three groups, characterized as teachers with negative PI (group I), teachers with positive PI (group II), and uncommitted teachers (group III), would also need to be confirmed. The characteristics of each group need further investigation, particularly with regard to possible influence that they may exercise in the educational process. The three groups evolved in this study would need to be confirmed for mathematics teachers and other secondary school subject teachers. Considerable differences were recorded mainly among group II and the other two groups. These differences were more intensive regarding work motivation, professional commitment, and future perspective. On the contrary, the differences that appeared among the group I and group III in the quantitative part were missing in the qualitative analysis. This can be attributed to the methodological weakness of Cluster analysis, which is one of the limitations of this study. Furthermore, when self-reporting instruments are used, there is always the risk that respondents provide “politically correct” answers. Although the respondents were guaranteed anonymity, this factor cannot be ruled out entirely. Even though such instruments make it practical to collect data for large-scale studies and offer the possibility of generalized findings, they necessarily sacrifice much of the complexity that can be inferred from qualitative methods. It must be acknowledged that although the developed scale outlines the professional image of teachers, it must be supplemented by qualitative data in order to fully record their PI.

Another direction for further research concerns the examination of possible ways to enhance these ideas through pre-and-in-service educational programs or through special interventions. Teacher education programs may concentrate on developing positive PI, while teacher mentors may consider ways to help teachers change their negative PI or their “uncommitted” approach, two groups which comprise 66% of the teachers in the current sample. In addition, self-recognition of one’s own professional profile may work as a motive reconsideration of his self-beliefs (Alsup, 2006). Our interviews seem to indicate that this possibility is a realistic promise, particularly if we accept the view that PI is in a process of continual restructuring.

References

Adler, J., Ball, D. L., Krainer, K., Lin, F., & Jowotna, J. (2005). Reflections on an emerging field: Researching mathematics teacher education. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 60(3), 359–381.

Akkerman, S. F., & Meijer, P. C. (2011). A dialogical approach to conceptualize teacher identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(2), 308–319.

Alsup, J. (2006). Teacher identity discourses: Negotiating personal and professional spaces. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ball, S. J. (1972). Self and identity in the context of deviance: The case of criminal abortion. In R. Scott & J. Douglas (Eds.), Theoretical perspectives on deviance (pp. 158–186). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28(2), 117–148.

Beauchamp, C., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 175–189.

Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Τeacher Εducation, 20(2), 107–128.

Billig, M., Condor, S., Edwards, D., Gane, M., Middleton, D., & Radley, A. (1988). Ideological dilemmas: A social psychology of everyday thinking. London: Sage.

Bogler, R., & Somech, A. (2004). Influence of teacher empowerment on teachers’ organizational commitment, professional commitment and organizational citizenship behavior in schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(3), 277–289.

Bryman, A. (2006). Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qualitative Research, 6(1), 97–113.

Bullough, R. V. (2009). Seeking eudaimonia: The emotions in learning to teach and to mentor. In P. A. Schutz & M. Zembylas (Eds.), Advances in teacher emotion research: The impact on teachers’ lives (pp. 33–53). New York, NY: Springer.

Canrinus, E. T., Helms-Lorenz, M., Beijaard, D., Buitink, J., & Hofman, A. (2012). Self-efficacy, job satisfaction, motivation, and commitment: exploring the relationships between indicators of teachers’ professional identity. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 27(1), 115–132.

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Steca, P., & Malone, P. S. (2006). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of job satisfaction and students’ academic achievement: A study at the school level. Journal of School Psychology, 44(6), 473–490.

Chan, W. Y., Lau, S., Nie, Y., Lim, S., & Hogan, D. (2008). Organizational and personal predictors of teacher commitment: The mediating role of teacher efficacy and identification with school. American Educational Research Journal, 45(3), 597–630.

Charalambous, C. Y., Philippou, G. N., & Kyriakides, L. (2008). Tracing the development of preservice teachers’ efficacy beliefs in teaching mathematics during fieldwork. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 67(2), 125–142.

Day, C. (2002). School reform and transitions in teacher professionalism and identity. International Journal of Educational Research, 37(8), 677–692.

Day, C., Elliot, B., & Kington, A. (2005). Reform, standards and teacher identity: Challenges of sustaining commitment. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(5), 563–577.

Denessen, E. (1999). Attitudes towards education: Content and student orientedness in the Netherlands (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Radboud University Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Dinham, S., & Scott, C. (1998). A three domain model of teacher and school executive career satisfaction. Journal of Educational Administration, 36(4), 362–378.

Evans, L. (2001). Delving deeper into morale, job satisfaction and motivation among education professionals: Re-examining the leadership dimension. Educational Management & Administration, 29(3), 291–306.

Frade, C., & Gómez-Chacón, I. M. (2009). Researching identity and affect in mathematics education. In M. Tzekaki, M. Kaldrimidou & C. Sakonidis (Eds.), Proceedings of the 33rd Conference of the IGPME (Vol. 1, p. 376). Thessaloniki, Greece: PME.

Gee, J. P. (1990). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses. London, England: Falmer Press.

Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., & Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3), 255–274.

Hermans, H. J. M. (1996). Voicing the self: From information processing to dialogical interchange. Psychological Bulletin, 119(1), 31–50.

Hoy, W., & Spero, R. B. (2005). Changes in teacher efficacy during the early years of teaching: A comparison of four measures. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(4), 343–356.

Huberman, A. M., Grounauer, M., & Marti, J. (1993). The lives of teachers. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Johnson, B., & Turner, L. A. (2003). Data collection strategies in mixed methods research. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (pp. 297–319). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kagan, D. M. (1992). Implication of research on teacher belief. Educational Psychologist, 27(10), 65–90.

Kelchtermans, G. (1993). Getting the story, understanding the lives. From career stories to teachers’ professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 9(6), 443–456.

Kelchtermans, G. (2005). Teachers’ emotions in educational reforms: Self-understanding, vulnerable commitment and micropolitical literacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(8), 995–1006.

Kelchtermans, G. (2009). Who I am in how I teach is the message: Self-understanding, vulnerability and reflection. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 15(2), 257–272.

Kelchtermans, G., & Vandenberghe, R. (1994). Teachers’ professional development: A biographical perspective. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 26(1), 45–62.

Knowles, J. G. (1992). Models for understanding pre-service and beginning teachers’ biographies: Illustration from case studies. In I. F. Goodson (Ed.), Studying teachers’ lives (pp. 99–152). London, England: Routledge.

Krzywacki, H. & Hannula, M. S. (2010). Tension between present and ideal state of teacher identity in the core of professional development. In C. Frade & L. Meira (Eds.), Proceedings of the 34th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education. Belo Horizonte, Brazil: PME.

Kyriacou, C., & Coulthard, M. (2000). Undergraduates’ views of teaching as a career choice. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 26(2), 117–126.

Lamote, C., & Engels, N. (2010). The development of student teachers’ professional identity. European Journal of Teacher Education, 33(1), 3–18.

Lasky, S. (2005). A sociocultural approach to understanding teacher identity, agency and professional vulnerability in a context of secondary school reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(8), 899–916.

Latham, A. (1998). Teachers’ satisfaction. Educational Leadership, 55(5), 82–83.

Latham, G. P., & Pinder, C. C. (2005). Work motivation theory and research at the dawn of the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 485–516.

Lee, K., Carswell, J. J., & Allen, N. A. (2000). A meta-analytic review of occupational commitment: Relations with person- and work-related variables. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 799–811.

Loughran, J. (2006). A response to ‘reflecting on the self’. Reflective Practice, 7(1), 43–53.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, M. A. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nias, J. (1989). Primary teachers talking: A study of teaching as work. London, England: Routledge.

Olsen, B. (2010). Teaching for success: Developing your teacher identity in today’s classroom. Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2010). Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: A study of relations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4), 1059–1069.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Procedures and techniques for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Timostsuk, I., & Ugaste, A. (2010). Student teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(8), 1563–1570.

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805.

Tsui, K. T., & Cheng, Y. C. (1999). School organizational health and teacher commitment: A contingency study with multi-level analysis. Educational Research and Evaluation, 5(3), 249–268.

Tyree, A. K. (1996). Conceptualising and measuring commitment to high school teaching. Journal of Educational Research, 89(5), 295–304.

Van Driel, J. H., Bulte, A. M., & Verloop, N. (2005). The conceptions of chemistry teachers about teaching and learning in the context of a curriculum innovation. International Journal of Science Education, 27(3), 303–322.

Van Huizen, P. H. (2000). Becoming a teacher: Development of a professional identity by prospective teachers in the context of university - based teacher education. Doctoral dissertation. Utrecht, The Netherlands: University of Utrecht. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.180544.

Van Veen, K., & Sleegers, P. (2009). Teachers’ emotions in a context of reforms: To a deeper understanding of teachers and reform. In P. A. Schutz & M. Zembylas (Eds.), Advances in teacher emotion research: The impact on teachers’ lives (pp. 253–272). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Weiss, H. M. (2002). Deconstructing job satisfaction: Separating evaluations, beliefs and affective experiences. Human Resource Management Review, 12(2), 173–194.

Zembylas, M., & Papanastasiou, E. (2006). Sources of teacher job satisfaction and dissatisfaction in Cyprus. Compare, 36(2), 229–247.

Zigarelli, M. (1996). An empirical test of conclusions from effective schools research. Journal of Educational Research, 90(2), 103–109.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Karaolis, A., Philippou, G.N. (2019). Teachers’ Professional Identity. In: Hannula, M., Leder, G., Morselli, F., Vollstedt, M., Zhang, Q. (eds) Affect and Mathematics Education . ICME-13 Monographs. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13761-8_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13761-8_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-13760-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-13761-8

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)