Abstract

In the past, between the sixth century BCE and the ninth century CE, the Zapotec people managed rainwater in Monte Albán, in the state of Oaxaca, south of Mexico, through terraces, canals, dams, and wells. Water was a keystone of their worldview and ritual practice. Today, this knowledge is in oblivion. Rapid but irregular urbanization threatens the remnants of these water control systems, still hidden on this archaeological hill site. Our ongoing interdisciplinary project, Parque Monte Albán, has centered on the water that flows down the hill and offers new strategies to increase the value and quality of water by revitalizing and redesigning ancient hydraulic technology. In the short and long term, our solutions can restore the natural environment, improve the quality of urban living, and help protect archaeological heritage.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

The UNESCO World Heritage Site Yuanyang rice terraces in Yunnan, China, Wikimedia, Yulin Jia, released under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license

Introduction

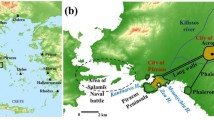

Monte Albán is an archaeological site in the south of Mexico, posed at the top of one of the three hills in the vicinity of Oaxaca City (shown in Fig. 1). The three-hundred- meter-long ceremonial plaza; dozens of temples, palaces, and residential areas; hundreds of tombs and artificial terraces visible on the slopes below; splendid ceramic effigy vessels; fine engraved stelae; and masterly worked jewelry have earned its status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In the last few decades, after twelve hundred years of decline, Monte Albán has faced a second round of rapid and uncontrolled urbanization, marked by a new informal city springing up primarily on its southern and eastern sides. Fences have been installed to protect the archaeological heritage of Monte Albán, but they have not stopped people from building houses and reaching the top. Lamentably, this unplanned urbanization has been unable to guarantee even basic necessities to the new settlers.

The natural environment is also under serious threat. Deforestation is causing unstoppable erosion. Without trees, rainwater is not held in their root systems, and instead runoff on the hill is exponentially increased, raising the number of flood events. New houses, streets, and infrastructure obstruct the runoff water that could otherwise flow into streams or come out of springs as it moves to reach Río Atoyac, the main river at the base of the valley. Moreover, the new inhabitants contaminate the water with their waste. Furthermore, climate change has caused this area to suffer ever heavier storms and harsher droughts. Residents who have settled at the very top of the hill are more vulnerable than others, since urban services cannot reach them or are simply unavailable because of the greater concentration of archaeological remains.

Our work explores solutions to these problems of water, heritage, and urban life in Monte Albán. Our aim is to recover the flow of water and improve the quality of life of the new informal city by using archaeological knowledge, cultural values, and social participation. We build on earlier projects conducted from 2012 to 2014 that studied the condition of the Río Atoyac and confirmed its deterioration–caused mainly by pollution and disposed sewage from Oaxaca City (Visión del Río Atoyac, Oaxaca 2012; Duurzaam Stedelijk Waterbeheer Oaxaca 2013–2014). These studies proposed several pathways to end contamination of the water. However, short terms in office of local authorities and lack of funding have obliged us to focus on smaller subprojects and segments of the larger project designed to rehabilitate the river. We find it useful to draw on the concept of acupuncture to develop strategies for more effective water management, envisioning that small pinpoints of improvement can help heal the overall body of the landscape and its arteries of water. One of the areas where it is viable to apply this healing acupuncture is the hill of Monte Albán and the streams and waters running from it to the Río Atoyac.

The stunning archaeological setting and great cultural and historical value of Monte Albán invited us to look closely at and learn from the ways that the site’s ancient inhabitants, the Zapotec people, controlled rain and groundwater. This past culture of respect for water, rain, and lightning inspired us to bring back, or to remember, that culture through archaeological research. Thus, our design project Parque Monte Albán was born.

From the moment of contact, Europeans began the massive destruction and alteration of indigenous water control systems. Revealing how these systems worked, and in some cases critically assessing them, as well as recovering this knowledge and improving it with modern urban and hydrological expertise and technology, allows us to address current water problems. Solutions for contemporary challenges can be found in local knowledge rather than in importing foreign technologies, or, even worse, by imposing them–as it happened five hundred years ago. We investigated the technology Zapotec people used to manage water along with the ways in which they valued water culturally. While conducting our work, we proposed a range of subprojects to improve urban life, actively involving local people to develop strategies so that awareness of the vulnerable archaeological heritage of Monte Albán and the crucial role of water there could be developed.

By continuing to both investigate the history of control of the water at the site and to learn more about both effective and failing strategies, we can elicit ideas and actions to prevent floods and provide freshwater to current occupants of the site. Moreover, there is an urgency to change how these problems are viewed. Rather than considering the new houses on the ancient site as an illegal invasion, we have to consider the deep social problem–which is rooted in economic marginalization and social rejection–behind it. This project conceives of long-term solutions as well as, more importantly, solutions that can be sustained and maintained by society: by those who live daily with the current problems of water, heritage destruction, and social exclusion. Rather than perceiving local people as the “enemies” that cause these issues, we see them as the best allies possible in the effort to protect the site. The same goes for rain: We should stop seeing it as the hostile party. Rainwater is good fortune today, as it was for the ancient Zapotecs, a blessing and benefit to society.

Monte Albán and Water

Monte Albán was founded in five hundred BCE, the earliest urban center in Middle America. At its height, from 450 to 600 CE, it had more than two thousand terraces inhabited by nearly thirty thousand people (Blanton 1978, p. 30). With temple pyramids surrounding its large plaza, Monte Albán is also considered the most important religious center of its time. It sat at the core of the Mesoamerican cultural region and was visited by thousands of people from the surrounding areas and far away alike (Joyce 2004). Monte Albán’s main deity, for its more than one thousand years of active use, was Cociyo, the deity of water and rain whose name literally means lightning in the Zapotec language (Cruz 1946). Cociyo was responsible for breaking the clouds with his “serpent of fire”—lightning—and bringing rain to the agricultural communities that depended on him to grow maize. Cociyo is most frequently represented by the shape of effigy vessels that are found interred in tombs. Most of these are now in private and museum collections (Marcus and Flannery 1994; Sellen 2002; Urcid 2009). Cociyo also appears engraved on stelae, as his name was apparently one of the names used by rulers and authorities (Urcid 2001; Jansen and Oudijk 1998). This historical reverence for the god of thunder and lightning at Monte Alban, in combination with the carefully engineered systems, stands in stark contrast to the disrespectful attitudes toward water today, a time when people pollute and obstruct watercourses.

Although the religious side of water seems well understood, scholars have overlooked the water control systems at Monte Albán. A prominent interpretation is that the site is a hill with no water. Scholars who have studied the evolution of the site, from its foundation to its decline, have suggested that Monte Albán was created as a neutral “disembedded” capital for a confederation which used the site to defend itself from enemies and launch military attacks to control the region (Blanton et al. 1999, p. 65). This new center was strategically established on marginal, sinuous, and unproductive soil, without natural sources of water, and at a distance of more than four kilometers from the main river, Río Atoyac (Blanton 1978, p. 36; Flannery and Marcus 1983, p. 81; Wolf 1959, p. 97). This image of a “hill with no water” contradicts what our present project has shown on maps and has already been asserted: the presence of multiple streams and runoffs. In 2014, we were able to prove that ancient water control technology existed in some of these streams. Indeed, the Monte Albán site accords with the Mesoamerican concept of altepetl: the sacred hill that is a source of sustenance and, in particular, of water (Rojas 2017).

Preliminary Results of the Zapotec Water Technology Study

In 2014, we conducted a brief non-intrusive survey of Monte Albán (Rojas 2015). The aim was twofold: to locate water and to seek out ancient water management technology. We first mapped some of the streams from their origin and traced them into the city, inspecting conditions (we gauged level of pollution, the presence of obstruction, and, where redirection had taken place, whether water still ran) along with potential for being included in the improvement project. We targeted densely urban areas including Mexicapam, Chapultepec, and Montoya on the eastern side of Monte Albán, since financial support for this project came from Oaxaca City, of which these areas were a part. To identify the ancient technology that had managed the watercourse downhill, we surveyed several streams for evidence of human intervention.

Using satellite imagery and geographic information systems (GIS), we verified the existence of four streams on the eastern side (streams A, B, C, and D) which we had previously identified as originating at the top of Monte Albán, continuing down into the city (where they are obstructed by garbage, houses, and streets), and eventually flowing into concrete outfall structures (shown in Fig. 2). Stream C originates at the top of the hill, where it is fed by rainwater. Water then percolates into the ground, surfacing farther down, beneath the main road (at the Carretera Monte Albán), in the form of a spring. Here, neighbors have built a well, sheltering it from inclement weather with a cage; water comes through a hose out of the well to flow freely along the street (shown in Fig. 3). This spring, located only 1.5 km from the main plaza, confirms that the hill provides freshwater.

We documented canals and small reservoirs nearby of approximately thirty centimeters width in another stream (in Stream D), excavated from the bedrock. These bodies of water are similar to those found at another Zapotec site, Hierve el Agua (Doolittle 1989; Kirby 1973). Both sites prove that the surface has been modified by human hand to control and obtain water (shown in Fig. 4).

We also surveyed within the protected zone of Monte Albán, a terrain which is much less disturbed by recent human intervention. We walked the north and west sides of the hill, where other studies had previously found water management features (Neely 1967, 1972; Neely and O’Brien 1973; O’Brien et al. 1980). There, along approximately four hundred meters of what we called the north and south streams, we found thirty-four features that would have been placed there to manipulate the flow of water, that is to say, to stop, hold, drain, or divert water to adjacent terraces. The associated ceramic material, though small in sample size, dated to circa 500 BCE to 200 CE (Epoch 1 and Epoch 2 or the Danibaan and Niza phases) (Caso et al. 1967, pp. 24–25, 219 [Figs. 127, 185, 186c]).

Many of these features were wells that inhabitants had excavated in the course of the stream, either using the natural banks of the stream as walls or building walls from stones or a wattle-and-daub mixture (shown in Fig. 5b, d).

a Canal and reservoir in stream north; b circular well in stream south; c wall that intersects stream north; d stepped well next to wall and inside stream north; e large reservoir at the end of streams north and south; released under a Creative Commons—Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license

Canals, which were probably constructed to bring in water, were connected to some wells at the upstream edge (shown in Fig. 5a). Other wells had walled, V-shaped steps (at the point facing upstream). Some of these were cut from the bedrock, while others were made from stones and slabs in order to spread water over the terraced fields next to the stream.

A long wall of more than fifteen meters in length and 0.6 m in height crossed through one of the streams from north to south (shown in Fig. 5c). At the point at which this outstanding feature intersected with the stream–inside the stream gorge–there lays another V-shaped stepped feature made of modeled stones and slabs (shown in Fig. 5d). This formation seemed to be a sort of dam and a well; at its lowest point, it was of more than one meter in depth, and seems in its entirety to have functioned to spread water to terraces immediately.

Another feature worth noting was almost at the base of the hill: A large reservoir that seemed to be excavated into the bedrock was also modeled into a stepped shape (shown in Fig. 5e). It was at least two meters deep (making it similar to other reservoirs reported by O’Brien et al. 1980). This feature collected the water coming from both north and south streams, and it is probably connected to the so-called defensive wall some scholars have mentioned to be very close to this area (Blanton et al. 1999). The reservoir indicates that this presumed wall is more likely to have been a water management feature than a work used for military protection.

These archaeological features demonstrate that Zapotec people developed technology to control running waters on the hill, probably already in use since the site’s foundation. According to previous studies, water was stopped, retained, deviated, channelized, drained, and transferred to terraces for agricultural and possibly domestic purposes. These are the features that have inspired us to emphasize water flow in our initiatives for the Parque Monte Albán project. In fact, we will try to recover and rebuild some of these works.

Thinking of Solutions

During fieldwork in the urban areas of Mexicapam, Chapultepec, and Montoya, we were able to see that today’s inhabitants use water inefficiently. Rather than keeping the streams clean and sourcing their water from them, families throw garbage, sewage, and soapy water into the streams. They in addition buy water from companies that send tanker trucks to fill large containers (called tinacos) which are on top of or next to their houses (Fig. 6).

Overall, neighborhoods in this area are informal, marginalized, and lack urban services, including light, electricity, gas, and sanitary water. Most of the houses near the fence that protects the archaeological site have neither a supply of freshwater nor drain pipes. As their status is illegal, inhabitants have to also build their houses with perishable and fragile materials on steep slopes (Fig. 7). These factors make living there a constant risk. Even the maps clearly show the lack of open and green areas; our walks, however, revealed directly that there were no public places where people residents can sit, enjoy the shade of trees, exercise, or simply walk safely away—on sidewalks, for example—from passing vehicles. This stands in contrast to the Historic Center of Oaxaca City and its Zócalo. Public lighting is also lacking, which makes these places dark and at risk to crime–a fact which was confirmed by the Comunidad Segura (2014) report, prepared by a civic organization that measures crime rates statistically in Oaxaca City, noting the Monte Albán neighborhoods as most dangerous.

However, the area does have an abundance of water. And water is the principal axis of this project: Wherever there is water, there is also probably a suitable location for natural, urban, and heritage intervention. Our strategy for improvement focuses precisely on such sources of water, not only to defend them but also to use them as a trigger for improvements in domains like environmental recovery, heritage protection, and reconstruction of social bonds. Indeed, we propose to build parks featuring water.

Our proposal for the design of these parks has five parameters. Healthier water is the principal axis. Thoughtfully incorporating the technology of the ancient Zapotecs, improved by modern hydraulic expertise, the parks, as we envision them, will feature healthy and clean streams and will allow rainwater to infiltrate into the subsurface soil and aquifers. Local people will be able to collect water from streams or rainwater reservoirs. Greener areas will help make those streams healthy: The aim here is to generate more vegetation so as to stabilize the banks of the streams and enhance the absorption of rainwater. With the help of specialists, we will plant species appropriate for the type of soil and elevation on site. The parks will constitute living archaeology that incorporates Zapotec technologies of water management such as those we find in our survey and other researchers have reported. Wherever possible, we will revitalize the Monte Albán water management system that is in place and make it visible in the parks. We hope in this way to raise awareness of the cultural value of the site.

Along with these living connections to the past, the parks will have smart connections to the present. Sites will be well connected to roadways that make it easy to get to the archaeological site, the riverside of Río Atoyac, or even the historical center of Oaxaca City. The goal here is to enhance paths so as to allow safe transit for walking, running, and cycling.

Having transformed unattractive spaces into green, dignified, equipped places, we expect residents to appropriate them and start turning them into public areas with social appeal: areas that light up the community and are unattractive to criminals. This greater access to sports and recreation will improve families’ lives.

We believe that the only way to make this project succeed is to sustain it from the very bottom, that is, with the participation and social engagement of the people who day by day suffer from floods and scarcity of water, live next to or even on top of the archaeological heritage site, and experience urban, economic, and social exclusion. Their participation in finding solutions to the challenges of living on this hill: Developing concepts, making decisions, and even building will ensure that the projects not only materialized but also are maintained in the future. The parks themselves can help foster this engagement, as a new form of education: a new way of learning about the ecological, hydrological, and archaeological importance of this area. These green, hydrological, and public spaces can become a living solution for a variety of intertwined problems.

The Natural, Urban, and Social Environment

In order to sketch a plan for parks that deploys old and new technology to help water, people, and heritage, it is necessary to build on a wide range of information from different disciplines. We have already looked at the geographic features of the area (Proyecto Parque del Agua Monte Albán 2016). Moreover, we have built on others’ documentation of flora and fauna and have consulted expert botanists on how to restore the ecology of the area. We have mapped the type of soils, ground altitude, land tenure (communitarian, state-controlled or ejido, and private property), and the use of land (habitational, commercial, agricultural, as well as for urban development such as schools, sports or recreational areas, public buildings, churches, and the like) in order to understand the overlapping of spaces and the possibility of finding free ones. In this regard, we have considered other issues: population size, political division (according to varying jurisdictions of municipality, agency, and neighborhood), standing legislation regarding urban settlement, and the system of roadways. The final variables in the plan were current management of archaeological sites, the existence of archaeological remains in the area, and other cultural traits such as local traditions and festivities.

A critical layer in this matrix of information has been the hydrological features of the landscape at Monte Albán. It has been thoroughly studied by Deltares, a Dutch agency specializing in the research for developing water technology (Duurzaam Stedelijk Waterbeheer Oaxaca 2013–2014). Besides revealing the high number of water sources that pour down from the hill, Deltares has studied the features of the surface, its elevation, the Río Atoyac, and the great aquifer underneath the Great Valleys of Oaxaca, where Monte Albán sits. It has identified four different zones on the hill, documenting the problems in each and proposing solutions. The water originates in the upper area where it runs quickly down steep slopes and erodes soil. To halt erosion, Deltares proposes reforesting the slopes and building barriers such as terraces or dams. Urban obstacles block the streams and runoff on the two intermediate areas, in the high and low piedmonts. In addition to restoring vegetation and slowing down the flow water from steep slopes with terraces and walls, the proposed solution would allow water to flow cleanly through side canals and build wells to help rainwater infiltrate to the groundwater. The last area is closest to the valley’s bottom; it is also closest to the Río Atoyac. Here, the problem is flooding into urban areas. The solution is to allow water to follow its course to the river and drain into it.

All the data from these studies has been analyzed using a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats approach (see other examples of SWOT analysis in urban planning in Prestamburgo et al. 2016). To put this approach into practice, it was necessary to use these variables and set some criteria by which we could assign proper places to design and build the parks. First, we determined to establish limits and define a target area. We selected the area of five hundred meters around the protected site and decided to treat it as a buffer zone. Within this area, we searched for sources of water, such as a stream, the presence of runoff, or a spring, and an absence of urban infrastructure such as a house, buildings, road, or power and water supply. We preferred locations with trees—which meant there was a likelihood of running water nearby—or barren sites that would have room to replant vegetation. Given these considerations, we looked at the maps to find free spaces to site, design, and eventually build the parks. Next, we considered several additional variables: the presence of roads, commercial centers, population density, and the land as either private or communal property. Areas with low urban density, low population, and flexible land use, soft urban tissue, were identified as suited for locating the parks. Figure 8 shows the graphical results of the SWOT analysis, along with our proposals for park sites.

Social participation has been a key component of this research process. From the beginning, in this bottom-up project, we have invited the people who live along Río Atoyac to share ideas, problems, and needs with us. To date, in three separate meetings, local people have participated in talks and workshops with experts on water, urbanism, and archaeology. Local people have worked with authorities from neighborhood, agency, municipal, and state entities, to voice their views on how to solve water issues and to map out new strategies. These workshops have been very fruitful in creating a connection between all stakeholders. However, our main concern has been to center the people living on Monte Albán and, particularly, on the site itself in all our discussions and decisions.

Designing Solutions

From the beginning of this water and urban space study, we realized that it was no longer possible to create an ideal buffer park: a green zone with no construction around Monte Albán due to the dense urbanism and effective absence of free space on the eastern side of the site. Moreover, such an effort would be extremely costly and time consuming. Our acupuncture strategies, in which delimited projects modify a small space and improve its hydrological features, create slightly better conditions while being cost-effective. These may be as large as a planting three trees—or two, or, even, one—at a street corner, adding greenery along a sidewalk, or building small canals that could permit the flow of water. These small projects embrace out guiding principles: healthier water, greener areas, living archaeology, smart connections, social appeal, social engagement, and new form of education. In the long term, if placed well, in key spots, we expect them, in their turn, to trigger larger transformations. Our vision of them all together is as a green dotted line or strand of pearls.

To date, we have proposed eight of our acupuncture projects. Each one imagines new green space, revitalizes some part of the Zapotec water control systems, and adds urban and recreational infrastructure. We describe two of the more advanced projects below.

Ojito de Agua

The uniqueness of the Ojito de Agua site, and its great value, relies on the existence of a natural spring (shown in Fig. 3). The particular acupuncture strategy to be applied begins with respecting the water in the spring, the well that collects it, and the surface path that remains without concrete cover. One other particularity of this site is the presence of washtubs which people of Mexicapam neighborhood use for laundry. We propose making minor repairs to dramatically improve how the area looks and works. In particular, we would raise the washtubs, reinforce them with local materials–which could make them more comfortable to use– and add stones to the river bed to strengthen and protect them. We also propose adding entirely new elements to the site. The smallest of these would be benches, streetlights, and more plants (such as agaves and bougainvillea). More broadly, new terraces in the walls could prevent them from eroding, while also enclosing the spring; structures with a stepped shape, like those found in archaeological record, could keep the water on course while broadening its flow. A green floor and new reservoirs made from pots, following the historical model, can help water infiltrate into the ground. It may be possible to construct a canal along the nearby street, visible to the inhabitants (Fig. 9). These embellishments can also work to prevent crimes in the area, a principal concern of inhabitants and passersby.

La Crucecita

The value of the La Crucecita site lies in its social use. It is a space that has already been appropriated by the residents of Chapultepec: Every May 3, they use it to celebrate the Holy Cross Festival, a Catholic festivity that probably has roots in the precolonial period. The proposal to modify this area into a green space for families and to meet social and communal needs was an idea that raised strong enthusiasm among inhabitants. In this case, as with the other acupuncture projects, there is no need to make massive changes. Although it can already be seen that some erosion challenges will have to be met, the main aim here will be to reforest the area and put in place urban infrastructure to improve the atmosphere for the recreational, cultural, and religious activities already being held. This acupuncture intervention is also a great opportunity to connect the city and the archaeological park.

One peculiarity of the area is its undulating terrain. One task to be dealt with is to level these, restoring the historic defined terraces with green and permeable blocks to prevent erosion. This will add not only more space but beauty to the area, and it will be useful, as we will also add streetlights and urban furniture made from local materials. The terraces could include canals to bring water down the hill; an added wall could help control the water flow and allow local people to collect it for local use. This technology is similar to that of archaeological features found uphill.

One key element of the site is the large cross around which the people gather. Here, they are welcomed ceremonially, receive food, hold religious services, dance, and hold games. We propose to add a playground for children nearby whose floor should be made of some form of permeable cobblestone so that rainwater does not run off but filters into the subsoil. In some areas, these could be of local brick–which would result in a level surface. Trees such as pine, ocote, would cast shade to protect the children from the direct and often intense sunlight (Fig. 10).

Conclusion

Water can be the factor that triggers solving heritage problems at Monte Albán, at the same time resolving quality of living problems as well as those of water itself—addressing both consumption and harvesting needs. Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies (Neely 1967, 1972; Neely and O’Brien 1973; O’Brien et al. 1980; Sansores 1992) which lamentably have been neglected. We believe that this technology which has been documented in archaeological research may, to a certain extent, be revitalized. At the very least, it will be worthwhile to critically investigate and learn from it, since once—for more than a thousand years—it proved to be useful to a city of thirty thousand people.

Today, finding sustainable strategies to combat worldwide water crises is a crucial task (Millennium Development Goals of the United Nations 2014; World Water Council 2014). If we take no action, freshwater resources will soon become scarce while cities and their massive demands for energy will continue to bleed natural resources from the landscape. Climate change itself will only worsen the problem of flooding. Monte Albán constitutes a unique opportunity to learn from worldviews and water control technologies that deeply respected water. This case study offers an innovative methodology which may also be applied to solve water problems in regions and sites worldwide to achieve engineering and urban designs that are uniquely local and inspired by archaeological knowledge.

The acupuncture projects we have presented are low-cost strategies for bringing an urgently needed healing process to the urban environment. This model of working might be replicated in other urban areas where water, heritage, and unchecked development collide.

In the long term, our study also seeks to improve the connection between the archaeological site and the Historic Center of Oaxaca City, which is itself a UNESCO World Heritage Site because of its sixteenth-century Spanish architecture, gastronomy, and living culture. We ultimately expect to enhance synergy between the archaeological and contemporary parts of the city and, in this way, to soften the barriers between the formal and informal cities, that is, to integrate marginal areas into the formal city.

Finally, we hope that by once again learning ancient techniques of water management, we might recover and remember the respect ancient people had for water. We hope that the inspiration we get from the archaeology of ancient Zapotec peoples can be transmitted to people living in the present. This work is our attempt to honor the ancestors who built a magnificent city in the past and to bring a part of their memory to the present, to live among their heirs, who hopefully will defend it with a sense of pride.

References

Blanton RE (1978) Monte Albán: settlement patterns at the ancient Zapotec capital. Academic Press, New York

Blanton R, Feinman G, Kowalewski S, Nicholas Linda (1999) Ancient Oaxaca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Caso A, Bernal I, Acosta J (1967) La cerámica de Monte Albán. INAH, Mexico City.

Comunidad Segura (2014) Report of the Oaxacan organization affiliated to the safe community model (World Health Organization, Stockholm, Sweden). http://www.oaxacacomunidadsegura.org.mx/blog/?p=310. Accessed 30 November 2016

Cruz W (1946) Oaxaca recóndita. Linotipográficos Beatriz Silva, Mexico City

Doolittle WE (1989) Pocitos and registros: comments on water control features at Hierve el Agua, Oaxaca. American Antiquity 54(4):841–847

Duurzaam Stedelijk Waterbeheer Oaxaca (2013–2014) Project developed by Dutch agencies Deltares, Arcadis, and MAP Urban strategies, funded by the Oaxacan State government, the municipality of Oaxaca and Partners voor Water. Document in MAP Urban strategies’s archive

Jansen M, Oudijk M, Kröfges Peter (1998) The shadow of monte Albán: politics and historiography in postclassic Oaxaca, Mexico. CNWS, Leiden

Joyce A (2004) Sacred space and social relation in the valley of Oaxaca. In: Hendon Julia A, Joyce Rosemary A (eds) Mesoamerican archaeology. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, pp 192–216

Kirby AVT (1973) The use of land and water resources in the past and present valley of Oaxaca, Mexico, memoirs of the museum of anthropology, number 5, vol 1. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Marcus J, Flannery K (1994) Ancient Zapotec ritual and religion: an application of the direct historical approach. In: Renfrew Colin, Zubrow Ezra B (eds) The ancient mind: elements of cognitive archaeology. University of Cambridge Press, Cambridge, pp 55–74

Millennium Development Goals of United Nations (2014) http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals. Accessed 10 Oct 2014

Neely JA (1967) Organización hidráulica y sistemas de irrigación pre-históricos en el Valle de Oaxaca. Boletín del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia 27: 15–17

Neely JA (1972) Prehistoric domestic water supplies and irrigation systems at monte Albán, Oaxaca, Mexico. Paper presented at the 37th annual meeting of the society for American archaeology, Instituto Welte archive: 1–15

Neely JA, O’Brien MJ (1973) Irrigation and settlement nucleations at Monte Albán: a test of models. Paper presented at the 38th annual meeting of the society for American archaeology, Instituto Welte archive: 1–19

O’Brien MJ, Lewarch DE, Mason RD, Neely JA (1980) Functional analysis of water control features at monte Albán, Oaxaca, Mexico. World Archaeology 11(3):342–355

Prestamburgo S, Premru T, Secondo G (2016) Urban environment and natura. A methodological proposal for spaces’ reconnection in an ecosystem function. Sustainability 8(407):1–13

Proyecto Parque del Agua Monte Albán (2016) Memoria del proyecto Parque Metropolitano Ecológico del Agua, Área Monte Albán. Descriptive memory and studies done for the after mentioned project elaborated by MAP Urban Strategies and Arquinistas, manuscript in State Government of Oaxaca and authors’ archives

Rojas A (2015) Informe del recorrido en escurrimientos, arroyos y manantiales de Monte Albán (Verano 2014). Report in INAH, Mexico City, archive

Rojas A (2017) El agua en el cerro del Rayo: Nueva evidencia sobre la presencia y manejo del agua en Monte Albán. Revista Española de Antropología Americana 47: 15-42.

Sansores FJ (1992) El control del agua en Monte Albán, nuevas evidencias. Cuadernos de Arquitectura Mesoamericana 18:19–28

Sellen A (2002) Storm-God Impersonators from Ancient Oaxaca. Ancient Oaxaca 13:3–19

Urcid J (2001) Zapotec hieroglyphic writing. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington D.C

Urcid J (2009) Personajes enmascarados. El rayo, el trueno y la lluvia en Oaxaca. Arqueología Mexicana 16(96):30–34

Visión del Río Atoyac, Oaxaca (2012) Project developed by Dutch agencies MAP Urban strategies, Urhan and Deltares, funded by the government of the municipality of Oaxaca City. Portfolio in MAP Urban Strategies’s archive

Wolf E (1959) Sons of the shaking earth. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

World Water Council (2014) http://www.worldwatercouncil.org. Accessed 10 Oct 2014

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Deltares, in the Netherlands, and Arquinistas, in Mexico, for their work and support in the development of the project “Parque del Agua Monte Alban”. Our gratitude to the faculty of Archaeology of Leiden University, for the facilities given to make the archaeological survey in Monte Alban possible, as well as to Svenja Kerkhof, Nienke Verstraaten, Philippa Jorissen, and Tom Lovett for participating and involving in this project. Thanks to Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, in particular Dirección de la Zona Arqueològica de Monte Albàn and Coordinación Nacional de Arqueología, for conceding the permits required to conduct survey in Monte Alban. Our gratitude to Ana Osante for her skills in making maps and Sarah Kellar for the English revision of this text. This contribution was made possible by the support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 800253.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rojas, A., Beccan Dávila, N. (2020). Studying Ancient Water Management in Monte Albán, Mexico, to Solve Water Issues, Improve Urban Living, and Protect Heritage in the Present. In: Hein, C. (eds) Adaptive Strategies for Water Heritage. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00268-8_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00268-8_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-00267-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-00268-8

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)