Abstract

One of the most commonly diagnosed types of cancer at an older age is colorectal cancer (CRC). The median age at which CRC is diagnosed nowadays is 69 years. Due to the aging of the population and the fact that individuals between 80–89 years exhibit the highest risk of being diagnosed with CRC, the median age at diagnosis will further increase in the near future. An important feature of elderly cancer patients is the fact that they often present with comorbidity. Among patients with CRC, the prevalence of comorbidity has been increasing over the last decades. Among patients aged 80–89 years old the prevelance of comorbidity increased from almost 60% in 1995–1998 to 80% in 2007–2010. Also tumor location shows a relation with age. With the exception of appendiceal tumours, older age is related to a more proximal tumor location within the large bowel. Older patients are less often diagnosed with node positive disease, as wel as synchronous distant metastases. Also socio-economic status of patients with CRC shows a strong relation with age. Of patients younger than 55 years, 18% of the patients is of a low socio-economic status, while this amounts to 42% among patients aged 80 or above. Five-year elative survival of patients with CRC decreases by age, from 66% for patients younger than 45 years old, to 55% for patients older than 75 years. Survival has been improving recently also for elderly patients. This, together with the increase in incidence, will lead to an increased prevalence of elderly with CRC. This development will increasingly ask for investments in clinicalresearch and infrastructure with a special attention for the elderly patient with CRC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

In the forthcoming decennia the number of elderly will rise in the Western society, not only because the first postwar baby boomers have meanwhile reached the age of 65 but also because life expectancy continues to rise. The average life expectancy at birth in Europe is estimated to reach 89 years for women and 84.5 years for men in 2050 [1]. Since the risk of most of types of malignancies increases by age, the number of elderly patients with cancer consequently will increase as well. However, not only demographics are responsible but also lifestyle-related factors such as the increased prevalence of smoking among women and the changing patterns in sun exposure contribute to the expected increase in the number of patients with cancer. Last but not least, the ongoing drop in mortality of “competing” diseases such as cardiovascular diseases may as well partly be responsible for a further increase in the number of elderly patients who develop cancer. One of the most common types of cancer at older age is colorectal cancer. Between 65 and 85 years of age, it is the most common cancer together with lung and prostate cancer, while among individuals over the age of 85, colorectal cancer is most frequent together with skin and breast cancer [2]. Of all male patients with colon cancer, 91 % is over the age of 55, while 30 % is between 75 and 84 years old, and 7 % is 85 years or older at time of diagnosis. Among women even 13 % is aged 85 or older. Only non-melanoma cancer and cancer of the stomach and bladder are characterized by a higher proportion of patients aged 85 or more at time of diagnosis.

Incidence

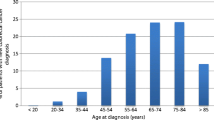

In Fig. 1.1 the age-specific incidence of colorectal cancer is depicted per 100.000 inhabitants of the same age group, separately for males and females [2]. As an example specific for the Western population, the figures from the Netherlands in 2010 are used. The age-specific incidence is higher among males than among females, at all ages. Although the median age at which colorectal cancer nowadays is diagnosed is about 69 years, in Fig. 1.1 it can be seen that the highest risk of being diagnosed with colorectal cancer is between 80 and 84 years for males and between 85 and 89 years for females. This means that with an aging population – hence growing proportions of people aged 80–89 years – the median age at which colorectal cancer is diagnosed will shift toward an even higher age in the near future.

Age-specific incidence of CRC (Source: Eindhoven Cancer Registry [4])

In the longstanding Eindhoven Cancer Registry in the Netherlands [3], trends over a longer period of time can be studied. When comparing the proportions of certain age groups over time with respect to age at diagnosis of colorectal cancer, it can be noted that the proportion of patients diagnosed below the age of 55 was 17 % in the period 1981–1985, which dropped to 10 % in 2005–2010. On the other hand, the proportion of patients diagnosed aged 75–79 increased from 14 to 17 % between 1981 and 1985 and 2005–2010, the proportion aged 80–84 increased from 9 to 12 %, and the proportion over 85 years of age increased from 5 to 8 %. This means that the total proportion of patients older than 75 has increased from 28 % in the beginning of the 1980s to 37 % in most recent years.

Gender

The male–female ratio is showing a U-curve when compared between the respective age groups. Among patients younger than 55 years, 45 % of the patients is female (source: Eindhoven Cancer Registry). This drops to 40 % at the age of 65–69 years, but then steadily increases up to 48 % females among patients aged 75–79, 56 % among patients aged 80–84, and above the age of 85 even 65 % is female. Although the risk of colorectal cancer within the older age groups remains higher among men as we learned from Fig. 1.1, women at older age outnumber men, thanks to their higher life expectancy. This U-shaped male–female ratio remained rather constant within the last three decades.

Comorbidity

An important feature of older cancer patients is the fact that they are more likely to present with comorbidity. In Fig. 1.2, the prevalence of various types of comorbidity at the time of diagnosis among patients with colorectal cancer is presented by age (source: Eindhoven Cancer Registry). Hypertension, cardiac disease, and previous malignancies (excluding basal cell carcinoma of the skin) are the most frequent comorbid diseases. A large increase for all types of comorbidity with increasing age can be noted, the age-related increase being largest for cardiac disease. The prevalence of comorbidity keeps increasing up to the patient category aged 80–89 years, thereafter the prevalence slightly decreases, which may in part be explained by some underreporting or by a selection of fitter patients who lived long enough to develop cancer. Also striking is the high proportion of patients with previous malignancies – up to 22 % of patients aged 80–89 already had a previous diagnosis of cancer. From Fig. 1.3 it becomes clear that the prevalence of comorbidity is increasing over time, across all age groups. Of patients aged 70–79, 57 % suffered from comorbidity in 1995–1998, which rose to 72 % in 2007–2010. For patients aged 80–89, almost 80 % had comorbidity in the most recent period. Also after adjustment for age, the increase in prevalence of comorbidity among patients with colorectal cancer remained significant. Looking at the various types of comorbidity, there was, for example, no increase in COPD, but there were large increases on the other hand for diet- and physical activity-related comorbidity such as hypertension, cardiac disease, and diabetes. The prevalence of diabetes, for example, rose from 9 to 18 % among patients with colon cancer. In view of the effects of comorbid diseases such as diabetes on treatment and outcome, it is of high importance to address this issue in research and policy in terms of both prevention and management of colorectal cancer.

Age-specific prevalence of comorbidity among patients with CRC, according to comorbid condition (Source: Eindhoven Cancer Registry [4])

Age-specific prevalence of comorbidity among patients with CRC, according to period of diagnosis (Source: Eindhoven Cancer Registry [4])

Anatomical Subsite

The distribution of tumors within the colorectum shows a strong relation with age. With respect to tumors located in the appendix, there is a clear preponderance for younger patients below the age of 55: 38 % of all patients who are diagnosed with an appendiceal tumor – which is a relatively uncommon tumor – is younger than 55 years (source: Eindhoven Cancer Registry). Two percent of all patients with colorectal cancer at this age has an appendiceal tumor, compared with 0.2 % of patients over the age of 85.

Nine percent of patients younger than 55 has a tumor located in the coecum, which becomes a more frequent tumor location with increasing age: of patients older than 85, 17 % has a coecum tumor. The same pattern can be observed in the colon ascendens, where 5 % of younger patients has their tumor located, compared to 12 % of the oldest patients. More distal, the pattern starts to change; in the colonic sigmoid, there is a U-shaped relation with age: somewhat less common in the youngest or oldest patients, but most common for patients 65–75 years old. Among patients younger than 55 years, 38 % has a tumor located in the rectum, while among patients over the age of 85, 24 % has rectal cancer. In general, with the exception of appendiceal tumors, older age is related to a more proximal tumor location. Remarkably, this relation is strengthening over time: for example, the proportion of patients under 55 years with a rectal tumor has increased over time, while in 1981–1985, 28 % of young patients was diagnosed with rectal cancer, this has now increased to 42 %. When choosing screening or diagnostic tools, this may be of importance, for example, sigmoidoscopy is more likely to miss tumors among older patients.

Stage at Diagnosis

Postoperative T stage is related to age to a certain degree: of patients who underwent resection younger than 55 years old, 9 % is diagnosed with pT1, while for patients aged 85 years or older, this is 7 % (source: Eindhoven Cancer Registry). This proportion drops from 19 to 15 % for pT2 and increases from 54 to 61 % for pT3. Interestingly the proportion of pT4 does not change with age: it comprises about 9 % at all ages. Also pTx remains constant over the age categories, at about 3 %. Concerning pN stage, the proportion with pN0 disease increases by age from 42 % among patients younger than 55–50 % among patients aged 80 or older. In this respect, it is of importance that the number of lymph nodes evaluated by the pathologist decreases by age. Finally, the proportion of patients with a positive M stage (including patients not operated on) decreases by age: from 25 % among patients younger than 55–13 % among patients aged 85 or older. This goes together with an age-related increase in the proportion with an unknown M stage. Probably, diagnostic procedures are used more sparingly among patients with a more limited life expectancy due to age and/or comorbidity.

Socioeconomic Status

There is a strong relation between socioeconomic status (SES) and age at diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Of patients diagnosed below the age of 55, 18 % is of low SES, while this amounts up to 42 % of patients aged 85 or older (source: Eindhoven Cancer Registry). Of the older group of patients, not surprisingly, a large proportion does not live independent anymore; 6 % of patients aged 75–79, 12 % of patients aged 80–84, and 23 % of patients over the age of 85 is residing in a nursing home or is otherwise institutionalized at time of colorectal cancer diagnosis.

Survival

The relative survival of patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer is decreasing by age; however, the age-related decrease is not dramatically high. One-year relative survival of patients with colon cancer is 86 % for patients younger than 45 years, 82 % for patients aged 45–54 years, 82 % for 55–64 years, 79 % for 65–74 years, and 69 % for patients older than 75 years [2]. The 5-year relative survival rates of the corresponding age groups are, respectively, 66, 60, 60, 59, and 55 %. For patients with rectal cancer, 1-year relative survival rates are 91 % for patients younger than 45 years, 89 % for patients aged 45–54 years, 88 % for 55–64 years, 84 % for 65–74 years, and 73 % for patients older than 75 years. The figures for 5-year survival of rectal cancer are 66, 65, 64, 62, and 52 % for the different age groups, respectively. In the last three decades, survival of rectal cancer has improved more than survival of colon cancer, thanks to positive developments in the treatment of rectal cancer, which will be addressed in other chapters in this book. Although several studies did not show improved survival rates for elderly with colorectal cancer, more recent studies do show a survival improvement also for the elderly, albeit smaller than among younger patients. Also elderly patients therefore seem to benefit from the developments in management of colorectal cancer.

Prevalence

The prevalence of colorectal cancer (meaning the sum of all patients with a colorectal cancer alive at a certain moment after diagnosis) is increasing due to the rise in incidence and the improved survival. This means that the weight that these patients put on the health system in terms of follow-up or treatment-related morbidity is growing. Within only 5 years, the 10-years prevalence (the number of patients alive who have had a diagnosis of colorectal cancer in the past 10 years) has risen in the Netherlands with almost 10,000 patients: from 50,417 patients in 2007 to 60,155 patients in 2011 [2]. This means a 20 % increase within only 5 years. This development is not expected to slow down in the forthcoming years; projections estimate a further increase in prevalence to over 90,000 patients in 2020 (so doubled within 14 years), a situation which is representative for Western Europe [4].

Conclusion

The number of elderly patients with colorectal cancer will continue in the forthcoming years. It is and will remain one of the most frequent cancers at high age. The median age at diagnosis will increase as well, which will go together with a higher prevalence of comorbidity. Besides this age-related increase in comorbidity, comorbidity itself is becoming more and more prevalent among patients with colorectal cancer probably related to lifestyle. Thanks to improvements in survival, recently also for elderly patients with colorectal cancer, the prevalence of cancer has been increasing. All of these developments will increasingly ask for investments in clinical research and infrastructure with a special attention for the elderly patient with colorectal cancer.

References

EUROSTAT. Available from http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Accessed on June 1, 2012.

The Netherlands Cancer Registry. Available from http://www.cijfersoverkanker.nl. Accessed on June 1, 2012.

Eindhoven Cancer Registry. Comprehensive Cancer Centre South. Available from www.ikz.nl. Accessed on June 1, 2012.

Dutch Cancer Society. Cancer in the Netherlands until 2020. Trends and prognoses. Amsterdam; 2011.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer-Verlag London

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lemmens, V.E.P.P. (2013). The Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer in Older Patients. In: Papamichael, D., Audisio, R. (eds) Management of Colorectal Cancers in Older People. Springer, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-85729-984-0_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-85729-984-0_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, London

Print ISBN: 978-0-85729-983-3

Online ISBN: 978-0-85729-984-0

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)