Abstract

The year 2015 saw the adoption of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the Paris Agreement. These landmark UN agreements both characterise and present the opportunity for developing integrated responses and coherence to the challenges bridging development, humanitarian, climate and disaster risk reduction areas. This chapter will provide examples of experiences and best practices from the international arena that identify how approaches to SDGs, Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) and Management (DRM), and Climate Change Adaptation (CCA) are juxtaposed, and the policy instruments currently in place that address SDG, DRR and CCA activities and actions. The text will consider opportunities for developing a concept of resilience that integrates SDG, DRR and CCA frameworks in response to global challenges, thereby constituting a development continuum instead of a series of independent and isolated phenomena. It will also identify and characterise opportunities for synergies across the different domains for community and sector vulnerability at local, national and international scales through integrated reporting across agreements.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

The year 2015 signalled a rare yet significantdevelopment in evolving global responses to global challenges, resulting in the adoption of a series of UN agreements, including the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR), the 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement (Murray et al., 2017; UN, 2015; UNFCCC, 2015; UNISDR, 2015b).Allthree agreements were, in part, evolutions from previous instruments and signalled recognition that responses to change needed to alter from a reactive and reduction focus to one that builds resilience before, during and after change (Tozier de la Poterie & Baudoin, 2015). Research over the past decades has identified global challenges arising from mankind’s developmentpathways that are increasingly impacting and superseding earth’s natural systems, and are unsustainable (ICSU & ISSC, 2010; Mizutori, 2019). As a result, countries are faced with the growing challenge of managing increasing risks from climate change and climate variability, addressing increasing frequency and intensity of extreme events, and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (Handmer et al., 2019; OECD, 2020).

The three agreements differ in structure, legal context and implementation mechanisms but share a common timeline running to 2030, as well as many parallels, particularly in the sense of their overall objectives (Dazé et al., 2018; Kelman, 2017a; UNFCCC, 2017). None of the frameworks engage with the full range of riskdrivers of global environmental change, yet their interconnectedness provides an urgent basis for coherent implementation in keeping with the expectations and aspirations of modern world societies (Handmer et al., 2019; Ochs et al., 2020; OECD, 2020; UNISDR, 2015a; Paterson & Guida, this volume). The 2030 Agenda and the SDGs outline targets for a holistic plan of action for people, planet, prosperity, peace and partnerships to which the Paris Agreement and Sendai Framework pose specific drivers of change, as well as pressures that challenge the future achievement of these goals. However, even though they address pressures that are at variance with each other in time and space, ultimately, all of these agendas are about protecting the future of humanity on our planet, building resilience for individuals and communities at all scales and localities, and proactively mitigating their risk (Benzie et al., 2018; Challinor et al., 2018; Murphy, 2019; Murray et al., 2017).

A coherent response to and implementation of the three agendas are necessary because, for instance, extreme events are a fact of life in many areas of the world, but their frequency and magnitude can be increased by climate change, as can unsustainable practices that are the focus of the Sustainable Development Goals, thus acting as risk multipliers and altering the vulnerability and exposure profile of societies. Although it was recognised from the onset that these frameworks crossed existing policy areas and institutional arrangements (Dazé et al., 2018), coherence in their implementation has largely not materialised because of:

-

Institutional arrangements—there are a wide range of organisations responsible for managing hazard exposures and reducing vulnerability that often miss potential synergies and duplicate efforts (OECD, 2020).

-

Scales and spheres of concern—while the Paris Agreement addresses a largely global driver (climate change) that requires action starting from a national context, the Sendai Framework addresses more local impacts originating from short-term, high-magnitude, man-made disasters and naturalhazards that usually originate from elsewhere. The Sustainable Development Goals are more outcome-focused on protecting the planet and the peace and prosperity of mankind whatever the source of disturbance, man-made or natural (PLACARD, 2019; UNDP et al., 2013; UNISDR, 2015a).

The danger of not realising synergies and coherence across the three frameworks is to risk systemic and cascading impacts that will have a long-lasting negative effect on the livelihoods and wellbeing of people, economies and countries, undermining sustainable development. Although international opinion has emphasised incorporating both climate change action and disaster risk reduction needs into development mechanisms, in practice, national-to-localimplementation has remained largely sectoral and topic-focused. Building coherence across the three frameworks needs to overcome a range of challenges, as outlined below:

-

As each framework has its own institutional arrangement that has established a thematic expertise over time, the question is how to balance autonomy with integration that could lead to greater effectiveness in building resilience across societies.

-

Moreover, as each framework has built up its own independent knowledge base, challenges surround how to establish data management that allows for interrogation across disciplines and topics, as well as resolution for more informed policymaking, thereby building adaptive capacity for greater resilience across climate and disasterrisk and enabling sustainable development.

Overcoming these challenges requires a coherence of approache that will build partnerships and place the assessment of climate change and disaster risk reduction within a wider context of outcomes for sustainable development, framed by the goals and targets set out by the Sustainable Development Goals. This context recognises that the Sustainable Development Goals, climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction as drivers of change represent a set of aspirational human rights around societal choices for what constitutes future sustainability. Coherence provides an opportunity to merge technical information that assesses risk from changes identified under each agenda with strategic and operational approaches to climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction in sustainable development. This can be done horizontally across sectors, vertically at different levels of government, and, generally, through collaboration across stakeholder groups (Handmer et al., 2019; Murphy, 2019; OECD, 2020).

Such an approach recognises that exposure to risks increasingly has interdependencies and cascading effects within and across multiple sectors that cannot be addressed through any one of the agreements (GIZ, 2017; Kelman, 2017a). How this might be achieved is a sensitive issue because each agenda has its own procedural and technical requirements, especially in the context of measuring and reporting progress. Coherence should not be seen as a replacement for some areas of monitoring under each agenda but, rather, an opportunity for monitoring, reporting, verifying and evaluating their implementation across agendas for holistic, evidence-based, politicaldecision-making (Murphy, 2019; Ochs et al., 2020; OECD, 2020).

Resilience as an Integrating Concept

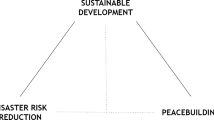

None of the agendas address the full spectrum of challenges that global changes present and, to a degree, each agenda has a focus on describing the elements that constitute risk through a particular lens, using different time frames, scales, sectors and hazards (Paterson & Guida, this volume). A way to take a unifying approach across the three agendas is through a focus that centres on outcomes, and moves from describing risk to describing resilience to risk, whatever its source; resilience is a concept common to all three agreements and is seen increasingly in other agreements and nationalstrategies (Handmer et al., 2019). Resilience recognises societies’ choices to address constituent elements that increase their exposure and vulnerability to change over short- and long-term horizons (Fig. 2.1), and provides a conceptual approach that engages with the full spectrum of shocks, stresses, disturbances and risk drivers to better reflect the range of risks that might affect a system (Carr, 2019; Lovell et al., 2016; Peters et al., 2016). Taken together, under the construct of the Sustainable Development Goals, the different approaches of climate change and frameworks make for a more complete ‘resilience agenda’ that spans the development, humanitarian, climate and disaster risk reduction arenas (Dovers & Handmer, 1992; Handmer et al., 2019; Opitz-stapleton et al., 2019; UNFCCC, 2017; UNISDR, 2017a). Alignment across the three Agendas provides the opportunity to realise development that is resilient not only to current but to future risk.

While each agenda has its own set of objectives and aligned indicators, the sustainability of each depends on the successful implementation of the others. Otherwise, this could potentially lead to conflictory and contradictory outcomes. The application of a resilience lens provides a means of connecting all three agendas that have measures relating to resilient development. (Source: Adapted from Peters et al. (2016), Alcántara-ayala et al. (2017), OECD (2020). Image: Hester Whyte)

‘Measuring’ Resilience

Synergies in monitoring and reporting provide opportunities for coherence through the interconnections between addressing climate change and disaster risk reduction, and achieving sustainable development (GIZ, 2017; UNFCCC, 2017). However, exploiting synergies is not without its own challenges:

-

The Paris Agreement, although not without global ambition, is primarily implemented at nationalscales and focusses on one driver of change, whereas the Sustainable Development Goals and Sendai Framework include other drivers of change and scales leading to different monitoring and reporting requirements (Table 2.1).

-

Although there are synergies between indicators for the Sustainable Development Goals and Sendai Framework, and the Sustainable Development Goals have one goal specifically addressing climate change, this intersection is absent between the Sendai Framework and the Paris Agreement, even though climate change will have significant impacts on the frequency and intensity of some disaster events.

In practical terms, this means that reporting under one framework cannot be assumed to cover the requirements of the other two frameworks, further supporting the notion that, while reporting requirements under all three agendas focus on input and output metrics, a focus on outcome metrics that address mankind’s resilience to change offers opportunity for coherence across the frameworks.

All three agendas include aspects that track across the other agendas (Fig. 2.1) with indicators to monitor progress towards defined targets at regional, national and local levels that address elements of ‘resilience’, and which encourage a shift from input and output indicators to outcome-based indicators (Adaptation Committee, 2018; UNDP, 2019; UNECE, 2020). Resilience as a core theme that unifies concepts across all three agendas provides an opportunity to develop solutions that address global challenges in the short to longer term, on local and internationalscales, and balances environmental, social and economic considerations. Achieving such coherency across agendas requires inconsistencies and contradictions to be identified between them, as well as synergies, and this, in turn, requires targets and indicators that measure progress and contribute to multiple outcomes (UNFCCC, 2017).

In practice, each agenda has progressed along largely siloed lines which makes little sense given the short window of opportunity for tackling the interlinked challenges of climate change, ecosystem degradation, inequality and other social, economic and politicalchallenges (GIZ, 2018), thereby missing opportunities for coherence building. Studies that have compared and contrasted indicators between the agendas have tended to focus on how indicators from one agenda can contribute to achieving targets from other agendas (e.g. Adaptation Committee, 2018). This has led to calls for greater development of metrics that allow for alignment of indicators across the three agendas (UNISDR, 2017a), requiring collaboration to collect relevant data and information, and shared national indicators (Adaptation Committee, 2018; Peters et al., 2016). Using the concept of resilience as a unifying characteristic provides an opportunity to fulfil technical objectives under each agenda whilst developing coherence in outcomes that contribute to sustainable development through country commitments under each agenda. Strategies for achieving the SDGs, Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) and National DRR strategies.

Bhamra (2015) proposes a set of economic, social, environmental and governance indicators for resilience, but these are not directly aligned to the architecture of the three agendas. Peters et al. (2016) have recognised that there is variance in the way that resilience is addressed in each agenda (Table 2.2). ODI (2016) and Schipper and Langston (2015) have assessed resilience in the context of resilient development and recommended exactly how each of the goals, targets and indicators across the agendas relates to one another and how they should be mapped, including points of coalescence and difference.

Developing Synergies Among Indicators

To date, synergies across the three agendas in the context of resilience have identified resilience-related indicators from one agenda that can be aligned with those in the other two agendas (Alcántara-ayala et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2016), but there is no common indicator set based on indicators shared across all three agendas. However, opportunities that connect the Sustainable Development Goals with the Sendai Framework (Fig. 2.2) and/or the Paris Agreement (Table 2.3) could lead to outcomes addressing the complex and interconnected social, economic and environmental elements that challenge resilience to societal and planetary risks (Lenton, 2020; Rockström et al., 2009).

Correlation between Sendai Framework global targets and SDG global targets through common indicators. (Source: Adapted from: https://www.preventionweb.net/sendai-framework/sendai-framework-monitor/common-indicators)

All three agendas include common ground that contributes towards building the resilience of people, economies and natural resources. Disaster risk reduction cuts across different aspects and sectors of development. There are 25 targets related to disaster risk reduction in 10 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, firmly establishing the role of disaster risk reduction as a core developmentstrategy with connections to resilience (PreventionWeb, 2019; UNISDR, 2015a). Equally synergies exist between climate action and the SDGs for resilience (UNDESA, 2019). For example, energy transitions envisaged in SDG 7, sustainable industrialisation under SDG 9, sustainable food production systems and resilient agricultural practices under SDG 2, and changing patterns of consumption and production in line with SDG 12 can all contribute towards resilience. However, in the case of climate adaptation, synergies with other agendas have tended to be oriented towards specific sectors.

Literature has emphasised the potential benefits of synergies in developing Monitoring and Evaluation frameworks in order to enhance societal and environmental resilience to change. Perhaps because of the stronger institutional structures addressing climate change, coordinated through the UNFCCC processes, many of these have been undertaken under the umbrella of climate change adaptation (Dzebo et al., 2017; GIZ, 2017; OECD, 2020; UNFCCC, 2017). In this context, resilience complements adaptation, in the sense that it invokes processes that secure flexibility in societal response, not only to current changes, but also to future changes, and as a way to embed these terms in wider notions of interconnected social, economic and environmentaldevelopment expectations/aspirations (see Nelson, 2011; Osbahr, 2007; UNEP, 2017; Vasseur & Jones, 2015). Whereas the Sustainable Development Goals and the Sendai Framework have indicator sets, the Paris Agreement does not. Measuring resilience is conceptually difficult as it is relative to the nature of the shock and the desired societal outcome (Levine, 2014; Nelson, 2011). However, a review of literature reveals a set of indicators from the Sustainable Development Goals and Sendai Framework that link adaptation to change and address vulnerabilities in order to strengthen resilience (Table 2.4), thus leading to outcomes that demonstrate capacity to adapt to stresses and changes, and to transform to more sustainable futures.

Tools for Revealing Links Across Agendas

In order for resilience to be an integrating measure across all three agendas, reflecting the goals and objectives of each of them individually, as well as collectively, tools are required to enable the analysis needed to support and realise the conceptual evaluation that has been described here. To date, tools have been developed that provide a degree of analysis and evaluation across pairs of agendas. For instance, the Sendai Monitor Framework tracks implementation of the Sendai Frameworktargets with related SDG Goals and Targets (see https://sdg.iisd.org/news/unisdr-launches-online-tool-to-track-progress-on-achieving-sendai-framework-sdgs/ and UNISDR (2017b); Poljanšek et al. (2019)); and both the SCAN tool (Gonzales-Zuñiga, 2018) and the NDC-SDG Connections tool (Dzebo et al., 2019) identify links between climate mitigationactions and the Sustainable Development Goals. There are currently no specific tools that identify links between climate change adaptation and the Sustainable Development Goals. The majority of the tools available visualise connections between agendas based on academic and grey literature, and do not afford a facility for an interactive and iterative interrogation of the linkages that allow practitioners to explore ‘what-if’ questions around how actions and/or changes in policy/management decisions in one agenda might affect another agenda. Interlinkages across the Sustainable Development Goals and their targets have been recognised (ICSU, 2017; Le Blanc, 2015; Miola et al., 2019) and recently, tools have been developed that allow for interactive engagement between stakeholders in order to ask ‘what-if’ questions on how progress in one area of development affects other areas (Weitz et al., 2018). This approach has been further developed to include additional elements other than the Sustainable Development Goals in the analysis, such as specific policy instruments (Le Tissier et al., 2020). This tool, for instance, (https://knowsdgs.jrc.ec.europa.eu/enablingsdgs) could be used to explore how the resilience elements within the three agendas connect and interlink with each other.

Conclusion

The adoption of the UN agreements of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its SDGs, and the Paris Agreement created an opportunity to build coherence between overlapping policyagendas that significantly affect the future of humanity. Although each addresses aspects for the future security and wellbeing of humanity – mankind’s ability to adapt to shocks that will materialise over varying scales in time and space – together, they provide a framing for resilience to risk, provided they can be implemented in support of each other (Kelman, 2017b). Each agenda recognises resilience as an integral feature for its implementation and success, and provides a means of building linkages and coordination to increase their effectiveness individually and collectively. This recognition is leading to the development of tools that could use shared targets and indicators across the three agendas and allow for alignment of policy and management processes in practice, thereby avoiding siloed approaches that have previously characterised the domains of climate change, disaster risk reduction and sustainabledevelopment.

References

Adaptation Committee. (2018). Expert Meeting on National Adaptation Goals/Indicators and Their Relationship with the Sustainable Development Goals and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. Available at: https://unfccc.int/node/180267. Accessed 7 Sep 2021.

Alcántara-ayala, I., Murray, V., Daniels, P., & Mcbean, G. (2017). Advancing Culture of Living with Landslides. Advancing Culture of Living with Landslides. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59469-9

Benzie, M., Adams, K. M., Roberts, E., Magnan, A. K., Persson, Å., Nadin, R., … Kirbyshire, A. (2018). Meeting the Global Challenge of Adaptation by Addressing Transboundary Climate Risk. SEI Briefs (April), 1–10. Available at: https://www.sei.org/publications/transboundary-climate-risk/. Accessed 9 May 2021.

Bhamra, A. S. (2015). Resilience Framework for Measuring Development. 1–4.

Carr, E. R. (2019). Properties and Projects: Reconciling Resilience and Transformation for Adaptation and Development. World Development, 122, 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.05.011

Challinor, A. J., Adger, W. N., Benton, T. G., Conway, D., Joshi, M., & Frame, D. (2018). Transmission of Climate Risks Across Sectors and Borders. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 376(2121). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2017.0301

Dazé, A., Terton, A., & Maass, M. (2018). Alignment to Advance Climate-Resilient Development. Retrieved from NAP Global Network website: http://napglobalnetwork.org/themes/ndc-nap-linkages/. Accessed 9 May 2021.

Dovers, S. R., & Handmer, J. W. (1992). Uncertainty, Sustainability and Change. Global Environmental Change, 2(4), 262–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/0959-3780(92)90044-8

Dzebo, A., Brandi, C., Janetschek, H., Savvidou, G., Adams, K., Chan, S., … SEI. (2017). Exploring Connections Between the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from Stockholm Environment Institute website: http://unfccc.int/focus/ndc_registry/items/9433.php. Accessed 9 May 2021.

Dzebo, A., Janetschek, H., Brandi, C., & Iacobuta, G. (2019). Connections Between the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda. Stockholm Environment Institute.

GIZ. (2017). Climate Change Policy Brief: Synergies in Monitoring the Implementation of the Paris Agreement, the SDGs and the Sendai Framework. Available at: http://www.adaptationcommunity.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/giz2017-en-cc-policy-brief-synergies-PA_SDG_SF.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2021.

GIZ. (2018). Connecting the Dots: Elements for a Joined-Up Implementation of the 2030 Agenda and Paris Agreement. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

Gonzales-Zuñiga, S. (2018). SCAN-Tool for Linking Climate Action and the SDGs the SDG Climate Action Nexus (SCAN) Tool: Mitigation Actions. NewClimate Institute.

Handmer, J., Stevance, A.-S., Rickards, L., & Nalau, J. (2019). Policy Brief: Achieving Risk Reduction Across Sendai, Paris and the SDGs. International Science Council.

ICSU. (2017). A Guide to SDG Interactions: From Science to Implementation. https://doi.org/10.24948/2017.01

ICSU & ISSC. (2010). Earth System Science for Global Sustainability. The Grand Challenges. International Council for Science (ICSU).

Kelman, I. (2017a). Linking Disaster Risk Reduction, Climate Change, and the Sustainable Development Goals. https://doi.org/10.1145/3132847.3132886

Kelman, I. (2017b). Linking Disaster Risk Reduction, Climate Change, and the Sustainable Development Goals. Disaster Prevention and Management, 26(3), 254–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-02-2017-0043

Le Blanc, D. (2015). Towards Integration at Last? The Sustainable Development Goals as a Network of Targets. Sustainable Development, 23(3), 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1582

Le Tissier, M., Whyte, H., & Stevance, A. (2020). Identifying Interactions for SDG Implementation in Ireland. GlobalGoals2020, 1–20. Available at: https://globalgoalsproject.eu/globalgoals2020/. Accessed 9 May 2021.

Lenton, T. M. (2020). Tipping Positive Change. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 375, 20190123. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0123

Levine, S. (2014). Assessing Resilience: Why Quantification Misses the Point. Overseas Development Institute.

Lovell, E., Bahadur, A., Tanner, T., & Morsi, H. (2016). Resilience – The Big Picture: Top Themes and Trends. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.2415.5767

Makinen, K., Prutsch, A., Karali, E., Leitner, M., Voller, S., Lyytimaki, J., … Vanneuville, W. (2018). Indicators for Adaptation to Climate Change at National Level – Lessons from Emerging Practice in Europe. https://doi.org/10.25424/CMCC/CLIMATE

Miola, A., Borchardt, S., Neher, F., & Buscaglia, D. (2019). Interlinkages and Policy Coherence for the Sustainable Development Goals Implementation: An Operational Method to Identify Trade-Offs and Co-Benefits in a Systemic Way. https://doi.org/10.2760/472928

Mizutori, M. (2019). From Risk to Resilience: Pathways for Sustainable Development. Progress in Disaster Science, 2, 100011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2019.100011

Murphy, D. (2019). Alignment of Country Efforts Under the 2030 Agenda, Paris Agreement and Sendai Framework. NAP Global Network.

Murray, V., Maini, R., Clarke, L., & Eltinay, N. (2017). Coherence Between the Sendai Framework, the SDGs, the Climate Agreement, New Urban Agenda and World Humanitarian Summit, and the Role of Science in Their Implementation. Retrieved from International Council for Science & Integrated Research on Disaster Risks website: https://council.science/cms/2017/05/DRR-policy-brief-5-coherence.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2021.

Nelson, D. R. (2011). Adaptation and Resilience: Responding to a Changing Climate. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 2(1), 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.91

Ochs, A., Indriunaite, L., & Engstroem, S. (2020). Towards Policy Coherence: An Assessment of Tools Linking the Climate, Environment and Sustainable Development Agendas. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

ODI. (2016). Analysis of Resilience Measurement Frameworks and Approaches. Retrieved from Overseas Development Institute website: https://www.fsnnetwork.org/sites/default/files/analysis_of_resilience_measurement_frameworks_and_approaches.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2021.

OECD. (2020). Common Ground Between the Paris Agreement and the Sendai Framework: Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction.

Opitz-stapleton, S., Nadin, R., Kellett, J., Calderone, M., Quevedo, A., Peters, K., & Mayhew, L. (2019). Risk-Informed Development from Crisis to Resilience. United Nations Development Programme.

Osbahr, H. (2007). Building Resilience: Adaptation Mechanisms and Mainstreaming for the Poor. In Human Development Report Occasional Paper. Retrieved from Background Paper for UNDP Human Development Report website: http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2007-2008/papers/Osbahr_Henny.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2021.

Peters, K., Langston, L., Tanner, T., & Bahadur, A. (2016). ‘Resilience’ Across the Post-2015 Frameworks: Towards Coherence? Retrieved from Overseas Development Institute website: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/11085.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2021.

PLACARD. (2019). Paris Agreement Through a DRR Lens. PLAtform for Climate Adaptation and Risk reDuction.

Poljanšek, K., Marin-Ferrer, M., Vernaccini, L., Marzi, S., & Messina, L. (2019). Review of the Sendai Framework Monitor and Sustainable Development Goals Indicators for Inclusion in the INFORM Global Risk Index, EUR 29753 EN. https://doi.org/10.2760/54937

PreventionWeb. (2019). Integrated Monitoring of the Global Targets of the Sendai Framework and the Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: https://www.preventionweb.net/sendai-framework/sendai-framework-monitor//common-indicators. Accessed 8 May 2021.

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin, F. S., Lambin, E. F., … Foley, J. A. (2009). A Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Nature, 461, 472–475.

Schipper, E. L. F., & Langston, L. (2015). A Comparative Overview of Resilience Measurement Frameworks: Analysing Indicators and Approaches. https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048526819-003

Tozier de la Poterie, A., & Baudoin, M. A. (2015). From Yokohama to Sendai: Approaches to Participation in International Disaster Risk Reduction Frameworks. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 6(2), 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-015-0053-6

UN. (2015). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from United Nations website: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/7891Transforming%20Our%20World.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2021.

UNDESA. (2019). Global Conference on Strengthening Synergies Between the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from United Nations website: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/25256WEB_version.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2021.

UNDP. (2019). Summary of Main Findings from SDG Mainstreaming, Acceleration and Policy Support Mission Reports. United Nations Development Programme.

UNDP, UNEP, UN_ESCAP, UNFCCC, UNISDR, & WMO. (2013). TST Issues Brief: Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/2301TST%20Issue%20Brief_CC&DRR_Final_4_Nov_final%20final.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2021.

UNECE. (2020). Towards Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in the UNECE Region. A Statistical Portrait of Progress and Challenges. United Nations.

UNEP. (2017). The Adaptation Gap Report 2017. Retrieved from United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Nairobi, Kenya website: https://www.unenvironment.org/resources/adaptation-gap-report-2017. Accessed 9 May 2021.

UNFCCC. (2015). Adoption of the Paris Agreement. Available at: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2021.

UNFCCC. (2017). Opportunities and Options for Integrating Climate Change Adaptation with the Sustainable Development Goals and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Fccc/Tp/2017/3, GE.17-1846 (October), 1–29. Available at: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2017/tp/03.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2021.

UNISDR. (2015a). Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A Reflection Paper Prepared by the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction.

UNISDR. (2015b). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Available at: https://doi.org/A/CONF.224/CRP.1. Accessed 9 May 2021.

UNISDR. (2017a). Coherence Between the Sendai Framework, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Climate Change. Available at: https://www.unisdr.org/files/globalplatform/592361be6e1b3Issue_Brief_-_Global_Platform_Plenary_on_Coherence_30.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2021.

UNISDR. (2017b). Technical Guidance for Monitoring and Reporting on Progress in Achieving the Global Targets of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction: Collection of Technical Notes on Data and Methodology. United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction Secretariat (UNISDR).

Vasseur, L., & Jones, M. (2015). Adaptation and Resilience in the Face of Climate Change: Protecting the Conditions of Emergence Through Good Governance. Retrieved from Brief for GSDR 2015 website: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/6579124-Vasseur-Adaptation%20and%20resilience%20in%20the%20face%20of%20climate%20change.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2021.

Weitz, N., Carlsen, H., Nilsson, M., & Skånberg, K. (2018). Towards Systemic and Contextual Priority Setting for Implementing the 2030 Agenda. Sustainability Science, 13(2), 531–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0470-0

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Le Tissier, M., Whyte, H. (2022). Why Does Making Connections Through Resilience Indicators Matter?. In: Flood, S., Jerez Columbié, Y., Le Tissier, M., O’Dwyer, B. (eds) Creating Resilient Futures. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80791-7_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80791-7_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-80790-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-80791-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)