Abstract

This paper addresses some coordinate structure types in Turkish, a head-final language. It proposes a constraint for head-final languages such that, even in word-order free head-final languages, the predicate must be clause-final: clauses must strictly represent the head-final property of the language. This constraint is parametrized, such that it is (near-)absolute for some head-final languages (e.g. Japanese), but limited to embedded clauses in others (e.g. Turkish). The predictions made by this constraint are borne out in Turkish: This constraint is illustrated for scrambling, for Yes/No questions, and for coordinate structures with identical predicates, showing that the ellipsis of that predicate obeys this parametrized constraint. This has immediate consequences for the directionality of such ellipsis: While both forward and backward ellipsis are possible in Turkish root clauses, only backward ellipsis is allowed in embedded clauses. Additional facts in coordinate structure with predicate ellipsis are shown to follow from this constraint, as well.

The present paper is related to Kornfilt (2000), a web publication, and to Kornfilt (2010), a non-refereed Festschrift publication. I propose here a different solution to the asymmetries between forward and backward ellipsis than in Kornfilt (2000); while the solution in the present paper is similar to that in Kornfilt (2010), neither the discussions nor the papers are identical. (Another somewhat related paper is Kornfilt (2012), where the focus is on “suspended affixation” in coordinate structures, whereby certain affixes are “shared” by conjuncts in a coordination.) I would like to thank Sumru Özsoy for her patience and trust in waiting for the present paper. Thanks are further due to two anonymous reviewers for their feedback, based on an abstract of this paper, and to two additional anonymous reviewers for their comments on a draft of this paper. I would like to also thank the following native speakers who shared their intuitions with me: Çiğdem Balım, Akgül Baylav, Cemal Beşkardeş, Demir Dinç, Jak Kornfilt, Alp Otman, and Ayşe Yazgan. I am particularly grateful to Cem Bozşahin for alerting me to his judgements, which differ from mine in two respects. The second difference led to the discovery of an interesting dialect split which is mentioned in this paper. All shortcomings of this study are my responsibility entirely. The abbreviations used in the glosses are as follows: 1.pl: first person plural; 1.sg: first person singular; 2.sg: second person singular; 3.sg: third person singular; acc: accusative; anom: action nominalization; fnom: factive nominalization; gen: genitive; neg: negation; prprog: present progressive; pst: past; q: yes/no question particle; subjunct: (root) subjunctive; vblconj: verbal conjunction particle.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

Gürer and Göksel (this volume) study the interplay between identical verb ellipsis and word order in Turkish, as well. Their main general claim is that the various possible and impossible instances of ellipsis cannot be explained by word order facts alone, but rather by information-structural considerations, with the latter being sufficient as explanations of all the relevant facts. Related to this claim is their suggestion that phonologcial phrasing patterns, “induced” by information-structural considerations, “interplay” with word order restrictions and “save” the structures that have been noted as unacceptable in the literature (and which are characterized as such in this article). That approach can be made compatible with the one I suggest in this article, especially given that I view the constraint that I propose not as a purely syntactic one, but rather one that applies at the level of PF. Thus, the constraint proposed here would hold for information-structurally unmarked utterances; utterances that are marked, leading to certain phonological phrasings, would not fall under the domain of the constraint, which is a “phonological” one in any case. The view that the application of the constraint to coordinate structures and to certain phenomena of predicate ellipsis (as well as to phenomena other than ellipsis) is a “phonological” one is thus compatible with the general view in the Gürer and Göksel article that underlines the importance of phonological phrasing for ellipsis, without making it necessary to subscribe to that paper’s claim that word order-based constraints are irrelevant for such ellipsis.

- 2.

A similar claim is made in Göksel and Özsoy (2000) for the treatment of focus, such that focus in Turkish is viewed as operating on strings rather than on structures.

- 3.

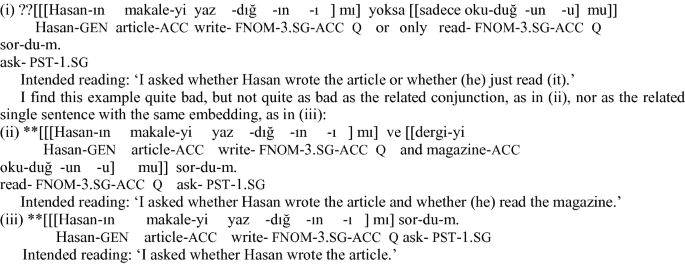

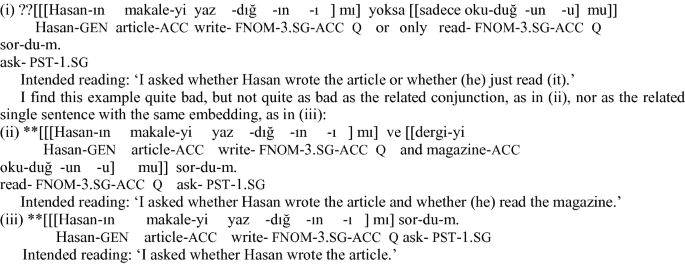

An anonymous referee, while (implicitly) accepting the reported judgment of (4b) as ill-formed, offers a disjunction of nominalized embedded clauses with each conjunct an embedded question, ending with the Yes/No question marker, and asks whether the example is grammatical or not, and if it is, what this would mean for the PFC. The example corresponds to the following one (I am building on the existing (4b), for the sake of simplicity):

The lesser degree of ill-formedness of the disjunction example may be due to a structural difference between disjunctions on the one hand, and embedded conjunctions or straightforward embeddings, on the other. I strongly suspect that in embedded disjunctions as in (i), we have an instance of “insubordination”, blocking the disjunction from being properly embedded and thus enabling it (at least at the level of a double question mark) to carry a matrix marker such as the Q-particle. Further research will show whether this hunch is on the right track.

- 4.

I use the general term of “ellipsis” or “Coordinate Ellipsis” (CE) as a descriptive, analysis-neutral term, while using terminology such as Right Node Raising (RNR), Forward Gapping and Backward Gapping (all of them instances of ellipsis) when I refer to a specific analysis.

- 5.

In such a structure, the “mother node”, i.e. the highest node of the coordinate structure, is not predicate-final; this is a problem for this approach (in addition to all the other problems mentioned in the text). The new analysis I propose in Sect. 6 does not face this problem, as the first conjunct in “forward Gapping” utterances is the phrasal head of the entire coordinate structure and thus determines the properties and syntactic features of the entire coordination. This is why the predicate of that first conjunct counts as the syntactic right edge of the entire coordination.

- 6.

In that work, another motivation was proposed: that there are no mirror-image rules in syntax. However, the status of this proposal is unclear, as I don’t know of any independent evidence in its favor. Therefore, I reject that motivation.

- 7.

In the article by Gürer and Göksel (this volume), different structures are proposed for forward and backward predicate ellipsis, as well.

- 8.

An anonymous referee finds (21) marginal; s/he states that this example would be well-formed only if the matrix verb is followed by a long pause. I don’t agree with this judgment; for my native consultants as well as for myself, the example is fine, as long as it is uttered with the low and flat pitch contour on the post-verbal embedded clause, i.e. with the intonational contour which is typical for post-verbal constituents in general.

- 9.

Constraints akin to this are proposed in Kuno (1973), although they are regarded as competence contraints and not performance constraints. It is possible, however, to have constraints of competence which are nevertheless motivated by performance factors.

- 10.

This is how the PFC would work in Turkish, where it is limited to internal positions. In Japanese, where it is not limited in this way, there shouldn’t be post-verbal coordinate structures anyway.

- 11.

Cem Bozşahin (personal communication) informs me that he accepts examples of this sort. For me, they are very bad, and the same is true for my native consultants. As a matter of fact, examples like (24), where the Case on the embedded nominalized clause and on the scrambled constituent is the same, are judged to be even worse than scrambling of this sort in general. Similar judgements have been reported elsewhere, too (e.g. Kennelly 1992; Kural 1997). There seems to be a dialect split here. For the purposes of the present study, I shall seek to account for the intuitions of speakers such as myself and the native consultants I have worked with.

- 12.

Such facts were, to my knowledge, first observed in Kornfilt (2000).

- 13.

An anonymous reviewer raises the question of when agreement “happens”, i.e. whether in narrow syntax or at PF, i.e. post-syntactically. I think that the facts presented in this study can be accounted for either way, but that the latter would be more in the spirit of the approach taken here. The reviewer further raises the question of whether the agreement facts reported here are computed in a linear way at PF, or in syntax, in a structural way. S/he reports that for her/him, a version of (31), but with the subjects and objects flipped, would be ill-formed, thus supporting a structural rather than linear approach. Given that the “flipped” version of (31) is fine for me and for a couple of other native speakers I was able to ask, this is a moot question. However, I believe that it is possible to account for the reviewer’s intuitions in a linear approach to agreement, as well.

- 14.

At the same time, the winner based on the hierarchy has to be closer to the surviving verb. Thus, if the subjects in (31) were to be flipped, the result would be ill-formed either with first person plural agreement (due to the first person subject being further removed from the surviving verb), or with second person plural (because the second person is lower on the hierarchy than the first person).

- 15.

Such adjunction is what we find in postverbal scrambling constructions in Turkish; cf., among others, Kornfilt (1998), Kural (1997). The difference between such constructions and the structure proposed here for coordinate constructions is that in postverbal scrambling, the adjunctions are transformational, i.e. the results of movement (=copy-and-deletion), while in the instances discussed here, we are dealing with adjunction in the phrase-structural component.

- 16.

Exclusion: B excludes A if no segment of B dominates A. (Chomsky 1986).

- 17.

Dominance: A is dominated by B only if A is dominated by every segment of B (Chomsky 1986).

- 18.

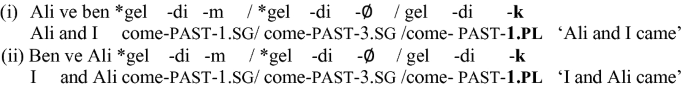

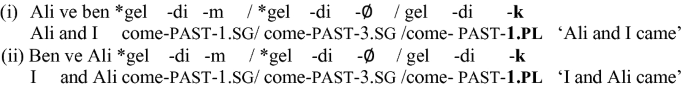

Note that in a dialect or idiolect such as Bozşahin’s, where the surviving verb in backward CE is allowed to agree with its own subject exclusively (thus resulting in acceptance of examples such as (30)), an alternative analysis is available where the highest segment of the adjunction category is not sensitive to the BP for agreement purposes. Note also that the BP’s person features must be accessible to the higher segment, i.e. the XP, in coordination of subjects in simple sentences, where of course there is only one verb which has to agree with its complex subject; e.g.:

The example relevant to the discussion in the text above is the grammaticality of (ii), in contrast with the flipped version of (31), as described in footnote 14 and discussed above. While I find (ii) not as good as (i), it is certainly acceptable. I will thus have to allow XP1 to access the person features of BP, when the BP is a simple DP, rather than a clause, as in all the examples of interest that are discussed in the body of the text.

- 19.

In a head-final language, the B-head of the BP should be on the right.

- 20.

An anonymous reviewer asks what “edge” means in this context. This is a term widely used in recent formal syntactic work, and refers to the specifier or the head of a constituent; here, it refers to the head of XP1, and, given that XP2 is the phrasal head of XP1, also to the head of XP2.

References

Bozşahin, C. 2003. Gapping and word order in Turkish. In Studies in Turkish linguistics: Proceedings of the tenth international conference in Turkish linguistics, ed. A.S. Özsoy, D. Akar, M. Nakipoğlu-Demiralp, E. E. Erguvanlı-Taylan, and A. Aksu-Koç, 95–104. Istanbul: Boğaziçi University Press.

Chomsky, N. 1986. Barriers. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

George, L., and J. Kornfilt. 1977. Infinitival double passives. In Proceedings of NELS VII, J. Kegl, D. Nash, and A. Zaenen, 65–79. Cambridge, Mass.: GLSA.

Göksel, A., and A.S. Özsoy. 2000. Is there a focus position in Turkish? In Studies on Turkish and Turkic languages: Proceedings of the ninth international conference on Turkish linguistics, ed. A. Göksel and C. Kerslake, 219–228. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Hankamer, J. 1971. Constraints on deletion in syntax. Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University.

Hankamer, J. 1972. On the nonexistence of mirror image rules in syntax. In Syntax and semantics, ed. J. Kimball, vol. 1, 199–212. New York and London: Seminar Press.

Huang, J. 1982. Logical relations in Chinese and the theory of grammar. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Kennelly, S. 1992. Turkish subordination: [-Tense, -CP, +Case]. In Modern studies in Turkish: Proceedings of the 6th international conference on Turkish linguistics, 55–75. Eskişehir: Eskişehir University.

Kornfilt, J. 1997. NP-movement and ‘restructuring’. In Current issues in comparative grammar, ed. R. Freidin, 121–147. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Kornfilt, J. 1998. On rightward movement in Turkish. In The Mainz meeting: Proceedings of the seventh international conference on Turkish linguistics, ed. L. Johanson, É.Á. Csató, V. Locke, A. Menz, and D. Winterling, 107–123. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Kornfilt, J. 2000. Directionality of identical verb deletion in Turkish. In An electronic Festschrift for Jorge Hankamer, ed. S. Chung and J. McCloskey. http://ling.ucsc.edu/Jorge/kornfilt.html.

Kornfilt, J. 2010. Remarks on some word order facts and Turkish coordination with identical verb ellipsis, In Trans-Turkic studies: Festschrift in honour of Marcel Erdal, ed. M. Kappler, M. Kirchner, and P. Zieme, 187–221. Istanbul: Pandora.

Kornfilt, J. 2012. Revisiting ‘suspended affixation’ and other coordinate mysteries. In Functional heads: The cartography of syntactic structures, ed. Laura Brugé, Anna Cardinaletti, Giuliana Giusti, Nicola Munaro, and Cecilia Poletto, 181–196. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kuno, S. 1973. Constraints on internal clauses and sentential subjects. Linguistic Inquiry 4 (3): 363–385.

Kural, M. 1997. Postverbal constituents in Turkish and the linear correspondence axiom. Linguistic Inquiry 28: 498–519.

Lees, R.B. 1968. The grammar of English nominalizations. The Hague: Mouton.

Munn, A. 1993. Topics in the syntax and semantics of coordinate structures. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maryland.

Munn, A. 1996. First conjunct agreement without government: A reply to Aoun, Benmamoun and Sportiche; ms.: Michigan State University.

Ross, J.R. 1967. Constraints on variables in syntax. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kornfilt, J. (2019). How to Derive the Directionality of Verb Ellipsis in Turkish Coordination from General Word Order. In: Özsoy, A. (eds) Word Order in Turkish. Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, vol 97. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11385-8_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11385-8_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-11384-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-11385-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)