Abstract

Virtual water is the water used or contaminated to produce a good or a service. With the large increase of export of agricultural produce during the last decades the amount of virtual water export has grown as well. Increased water contamination and water extraction for export from relative dry areas affects local ecosystems and communities. Simultaneously, the increased virtual water trade has weakened the local control over water resources by local communities, to the expense of multinational agribusiness and retailer companies. This repatterning of water control is fomented by numerous national governments, and at the same time contested by local communities. Partly as reaction to the critics on water depletion, agribusiness and retailers have created a number of water stewardship standards. Notwithstanding the possibilities for local communities to articulate their demands with these standards, until now most water stewardship standards have had little – or even negative – effects.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Virtual water represents the water used and contaminated to produce a product or service. Virtual water can be seen as “embedded” in products. It is an indicator of the amount of fresh water that evaporated or was contaminated during the production and transport of a product. Though the concept has been framed recently (e.g., Allan 1998), obviously, the practice of “virtual water trade” is as old as people have engaged in trade relations. Ancient empires as the Roman traded and transported large volumes of food throughout their territory and thereby, implicitly, conveyed huge quantities of virtual water across geographical scales (Dermody et al. 2014). Nevertheless, traditionally, even in the Roman Empire, food and water security were strongly location-fixed. Local communities and societies aiming for food security, therefore, needed to work on their local water security and availability, with local supply matching local demands (Vos 2010). With the huge expansion of global food trade throughout the last centuries and especially, over the last decades, this relationship between local water availability and food supply to the population of that same geographical location has been challenged profoundly: expansion of the global food trade implies virtual water export, it disconnects the place where water and food are produced from the place where it is consumed (Roth and Warner 2008; Sojamo et al. 2012).

First theories on virtual water (Allan 1998) presented it consequently as a potential solution to water scarcity, as these predicted that global market forces would direct virtual water flows from relatively wet to relatively dry regions. It would make use of regions” comparative advantages (water abundance) and solve other regions” disadvantages (lack of water to produce food). Evidence shows, however, that many water-poor countries like India, China, Kazakhstan and Tanzania are now net exporters, whereas water-rich countries like the Netherlands, UK, and Switzerland are net importers of virtual water (Hoekstra and Chapagain 2008; Ramirez-Vallejo and Rogers 2010). Clearly, the direction of virtual water flows is not primarily determined by water availability (Allan 2003). Recent critiques also point out the dangers of thinking in terms of “virtual water,” as the concept is an abstraction and thus conceals how economic power relationships and real water politics influence real livelihoods (Roth and Warner 2008).

One main drawback of the virtual water concept is that virtual water volumes do not express the social, environmental nor economic value of the water to local communities. For example: one cubic meter of soil water to produce pasture in the Netherlands for dairy and then export cheese, cannot be compared easily with one cubic meter of groundwater in the desert of Ica in Peru used to grow export asparagus. In the last case local communities rely on this water and do not have alternative ways to guarantee access to water for their survival and livelihoods, while in the Netherlands the cubic meter has very different social, environmental, and economic value, and is politically also contested but in very different ways. Nevertheless the concept of virtual water flow can be used to draw attention to an increasing use of water resources in regions where water is scarce. In that case the virtual water used for export agriculture is an indicator for social, political, and environmental risks. It can also be used to highlight the connectedness between producers and consumers of different regions in the world at different scales.

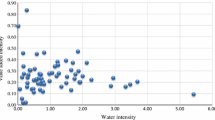

Some authors have suggested to add a water scarcity factor to include impact into the water footprint analysis: the so-called “stress-weighted water footprint” (e.g., Ridoutt and Pfitser 2010; Kounina et al. 2013). Examples of impact-based indicators of water footprints are those indicators that relate water use to water availability. Three examples are presented by Berger et al. (2014: 4523):

-

Risk of Freshwater Depletion (RFD): which defined by the Effective Water Consumption (WC) multiplied by Water Depletion Index (WDI). The WDI is an indicator of the irrigation water consumption related to the available water for irrigation in a river basin.

-

Consumption-to-availability (CTA), which relates annual water consumption with annual water availability.

-

Withdrawal-to-availability (WTA), which relates annual water withdrawal with annual water availability.

However, relative water scarcity is not a direct and universal indicator of ecological damage nor directly related to local economic opportunity costs of annual water use. For example, geographic and temporal scale effects make it difficult to assess social and ecological effects from comparing annual consumption (or withdrawal) and water availability. For example, water availability might be unequally distributed with a water basin, within the year, and among years. This makes that on the one hand water scarcity might be felt in certain places and periods when annual averages do no indicate any water scarcity problems. On the other hand transfer and storage of water can alleviate water scarcity. Moreover, other important local circumstances like cultural value of water and unequal distribution of benefits and costs of the use of the water are not included in the virtual water impact indicator.

The impact indicators are (explicitly or implicitly) claimed to be “universal” and therefore allow for comparison (“benchmarking”) among all places of the globe. However, the “impact indicators” do not take into account local history, justice nor ecological values. The indicators are not defined by local stakeholders or deprived groups, thus impeding those stakeholders to include evaluation criteria that would include their views and suite their needs and interests (see also Boelens and Vos 2012; Vos and Boelens 2014).

International trade of “luxury” products like fresh vegetables, fruits, and flowers doubled during the past decade, while also the export of for example biofuel crop production is booming. In dry and semi-arid regions, these high-water-consuming crops have in common that they compete for water and land with local communities, deplete and degenerate local ecosystems, worsen local and national food sovereignty, and alter existing modes of production and income distribution. For example, Peru increased tenfold its export of fruits and vegetables from the dry desert coast from 2001 to 2015 (Fig. 1). Ecuador tripled its flower export from the fragile—drought prone—Andean hill slopes North of Quito in the same period, and is now the third flower exporting country in the world (Fig. 2). Multinational and national companies have also acquired land and water rights to start large-scale production of sugarcane for biofuels in the desert North Coast of Peru showing sharp increase of export since 2008 (Fig. 3).

Export of fruits and vegetables from Peru (http://comtrade.un.org/db/)

Flower export from Ecuador (http://comtrade.un.org/db/)

Ethanol export for biofuels from Peru (USDA 2014)

Increased virtual water use by water-intensive crops in dry and semi-arid regions by agro-export companies increases the environmental consequences of depletion of surface and groundwater resources. Many river basins are “closing” (in closing river basins the river does no longer reach the sea in most part of the year) and groundwater tables are falling. In the North of Mexico, the Coast of Peru, the West of India, and many other parts of the world water tables drop with several meters per year. The dwindling water resources affect local communities and ecosystems (Hoogesteger and Wester 2015). Surface and ground water contamination by fertilizers and agrochemicals further affects local communities and ecosystems. Water supply to urban areas is also affected (see Oré et al. 2009; Woodhouse 2012; Yacoub et al. 2015). In all cases the poor suffer most from deteriorating water resources.

Political consequences of virtual water export by agribusiness companies are associated with the increase of control over water resources by the private sector companies, and consequently decrease of control by local communities and local and national governments. Many studies express how, more than ever before and regionally often in explosive trends, companies obtain water rights in legal and illegal ways, supported by Free Trade Agreements (Solanes and Jouravlev 2007). This supports water grabbing, affecting many smallholders in Africa, Asia, and Latin America (see, e.g., Mehta et al. 2012; Smaller and Mann 2009; Sultana and Loftus 2012; Venot and Clement 2013; Zoomers and Kaag 2013).

Multinational agribusiness and retailers react to the critiques, for instance, by developing water stewardship certification (Vos and Boelens 2014). Consumers in the North are increasingly aware of, and concerned about, their ecological footprint. Their pressure has led multinational companies to engage in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) mechanisms and claim “carbon-neutrality,” “ecological” production, or “fair trade.” Major agro-export companies use labels such as GlobalGAP and BRC, to certify product quality and the environmental sustainability of the production processes, as required by international supermarket chains (Fulponi 2007).

Recently, water has become “certifiable” as well. For example, the Alliance for Water Stewardship initiative by the WWF and other international organizations develops standards certifying that extracted water comes from sustainable sources (AWS 2011). For example, the widely used GlobalGAP scheme, but also the Rainforest Alliance, IFOAM, MPS-ABC flower industry certificate, and the standards of the multi-stakeholder “round tables” of the Better Cotton Initiative (BCI), Better Sugarcane Initiative (BSI), Round Table on Responsible Soy (RTRS) and the Roundtable on Sustainable Biofuels (RSB) include water criteria (Vos and Boelens 2014). These standards can potentially protect ecosystems and water users” communities against “water mining” and contamination by agro-export companies. However, it is worrisome that the social and environmental norms are set and monitored nearly exclusively by labeling entities from the North, without space for the voices and demands of local water users” collectives (see Bond 2008). Indeed, as we have detailed elsewhere (Vos and Boelens 2014), current certification practices bear the risk of exclusion, and reinforcement of existing social inequity. Important questions also remain about what certification schemes mean for the possibilities of (heterogeneous) smallholders to participate in international trade chains, which demand uniform production conditions and product qualities. Next is the question whether such schemes allow for monitoring and compensation of off-farm impacts of farm-based water extraction and pollution practices. Standards mainly focus on the farm level and not on the watershed nor community; and standards reinforce local inequalities by favoring and legitimizing presumably “efficient” water use technology like drip irrigation (mainly used by big land owners) and formal water rights (excluding communities with customary water rights). Discussion also continues on whether standards are effective to mobilize consumer power and actually hold companies accountable (Blowfield and Dolan 2008).

The Politics of Virtual Water Control

Many national governments develop new policies, including Free Trade Agreements and subsidies, to augment agricultural export. In different countries of the world, like Chile, Peru Ecuador, Mexico, Ghana, Senegal, Ethiopia, and Malaysia the development of roads, ports, airports, and/or irrigation systems is especially geared towards the agro-export sector. For example, the Peruvian Majes, Chavimochic and Olmos projects have invested more than 4000 million dollars of public resources in infrastructure to irrigate 225,000 ha, allocated mainly to a tiny minority of large (inter)national agribusinesses (Oré et al. 2009). Agribusiness companies also obtain water rights buying land with water rights from indebted smallholders, pressuring water authorities to grant new water rights for these arid lands, or (illegally) drilling deep tube wells. For example, in Piura, in the Peruvian dry North Coast, two large companies obtained water rights for 20,000 hectares of ethanol-oriented sugarcane production, part of which was exported. Simultaneously, local water user groups are denied water rights to expand their irrigated areas (Urteaga 2013).

In general, at an unprecedented scale, the “dis-embedding” of natural resources from public and common property rights frameworks (Boelens and Seemann 2014; de Vos et al. 2006), and their individualization and/or privatization and commoditization is a key mechanism allowing foreign agro-export companies to acquire the land- and water rights they need for profitable production (Achterhuis et al. 2010; Boelens and Vos 2012; Mehta et al. 2012; Swyngedouw 2005). The common strategy of transnational agribusiness enterprises is to maximize economic returns on investment by carefully identifying where they can obtain the cheapest and most timely supply of inputs (Smaller and Mann 2009). These “techno-institutional empires” (van der Ploeg 2008, 2010) therefore tend to invade territories to acquire low-costs resources, while permissive environmental and social legislation, combined with large subsidies, favor such strategies. The resulting repatterning of hydrosocial territories (Boelens et al. 2016) and its respective property relations also implies a thorough restructuring of labor relations and livelihoods to enable this accumulation process to occur (Zwarteveen and Boelens 2014; Swyngedouw 2005). While many people find employment in the new agro-export production sector—which may provide relatively stable incomes—the labor conditions (especially for women, as important employees) are often poor and insecure. When resources are depleted, when operations become less profitable, or when laborers are more organized, production moves to other regions.

Local and Multi-scalar Reactions

The growth of virtual water exports and the increased production of water-intensive crops by agro-businesses have important implications for how and where water is governed. Contestations over water resources that seem only local, sometimes “transnationalise” to become part of international debates over “fair” production. Reactions and resistance do not just include on-the-ground protests. To be successful, affected local actors need to forge multi-actor alliances that work on multi-scalar levels, thus creating civil society networks that are internally complementary while connecting the local, national, and global struggles for water justice. Examples exist in the mining sector [e.g., Bogaert (2015) for Morocco; Bebbington et al. (2010) for Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador; Ochoa (2006) and Stoltenborg and Boelens (2016) for Mexico; Urkidi (2010) for Chile]. Compared to mobilizations against mining sector extraction, so far, grassroots actions against water-extractive agribusiness exports have been limited at best, largely because of strong and deeply asymmetrical dependency ties within the sector (Vos and Boelens 2014). Local protests by water users” communities against water extraction by agribusiness have been documented in Ethiopia, Senegal, Tunisia, Mexico, Chile, Peru and Ecuador (Vos and Hinojosa 2016). In Spain the “New Water Culture” movement has had large influence in the change in national water policies, abandoning the National Hydrological Plan to bring water from the Ebro in the North of Spain to the South of Spain for export agriculture (Swyngedouw 2013, 2014).

Globalizing water extraction and virtual water exports deeply change existing labor-and property relations, weakening reaction capacity and generating new patterns of political control over water resources. Generally, at local scales, local collectives do devise strategies to cope with this repatterning of their livelihoods (Boelens 2015; van der Ploeg 2008). Increasingly, however, they now also aim to articulate their demands with international producer-consumer networks, fair trade and CSR initiatives at higher scales. Through such multi-actor networks they may complement their actions with advocacy and policy actors and strive to balance negotiation power, in order to defend their water and food sovereignty.

Domestic water use. Water for domestic purposes includes drinking water, use for public services, commercial service (such as hotels), and homes. There is huge variation in water use per person. Territory size shows the proportion of all water used for domestic purposes that was used there. Source www.worldmapper.org. Published with kind permission of © Copyright Benjamin D. Hennig (Worldmapper Project)

Agricultural water use. Between 1987 and 2003, on average 2.4 trillion m3 of water were used for agricultural purposes a year. Agricultural water includes that for irrigation and for livestock rearing. Territory size shows the proportion of all water used for agricultural purposes that was used there, 1987–2003. Source www.worldmapper.org. Published with kind permission of © Copyright Benjamin D. Hennig (Worldmapper Project)

References

Achterhuis, H., Boelens, R., & Zwarteveen, M. (2010). Water property relations and modern policy regimes: Neoliberal utopia and the disempowerment of collective action. In R. Boelens, D. Getches, & A. Guevara-Gil (Eds.), Out of the mainstream. Water rights, politics and identity (pp. 27–55). London and Washington DC: Earthscan.

Allan, J. A. (1998). Virtual water: A strategic resource. Global solutions to regional deficits. Ground Water, 26(4), 545–546.

Allan, J. A. (2003). Virtual water. The water, food, and trade nexus: Useful concept or misleading metaphor? Water International, 28(1), 106–113.

AWS. (2011). The Alliance for Water Stewardship water roundtable process. Final draft, April 20, 2011. London: Alliance for Water Stewardship.

Bebbington, A., Humphreys, D., & Bury, J. (2010). Federating and defending: Water, territory and extraction in the Andes. In R. Boelens, D. Getches, & A. Guevara (Eds.), Out of the mainstream: Water rights, politics and identity (pp. 307–327). London: Earthscan.

Berger, M., van der Ent, R., Eisner, S., Bach, V., & Finkbeiner, M. (2014). Water accounting and vulnerability evaluation (WAVE): Considering atmospheric evaporation recycling and the risk of freshwater depletion in water footprinting. Environmental Science & Technology, 48(8), 4521–4528.

Blowfield, M., & Dolan, C. (2008). Stewards of virtue? The ethical dilemma of CSR in African agriculture. Development and Change, 39(1), 1–23.

Boelens, R. (2015). Water, power and identity. The cultural politics of water in the Andes. London and Washington DC: Earthscan, Routledge.

Boelens, R., Hoogesteger, J., Swyngedouw, E., Vos, J., & Wester, P. (2016). Hydrosocial territories: A political ecology perspective. Water International, 41(1), 1–14.

Boelens, R., & Seemann, M. (2014). Forced engagements. Water security and local rights formalization in Yanque, Colca Valley, Peru. Human Organization, 73(1), 1–12.

Boelens, R., & Vos, J. (2012). The danger of naturalizing water policy concepts. Water productivity and efficiency discourses from field irrigation to virtual water trade. Agricultural Water Management, 108, 16–26.

Bogaert, K. (2015). The revolt of small towns: the meaning of Morocco”s history and the geography of social protests. Review of African Political Economy, 42(143), 124–140.

Bond, P. (2008). Social movements and corporate social responsibility in South Africa. Development and Change, 39(6), 1037–1052.

de Vos, H., Boelens, R., & Bustamante, R. (2006). Formal law and local water control in the Andean region: A fiercely contested field. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 22(1), 37–48.

Dermody, B. J., et al. (2014). A virtual water network of the Roman world. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 18, 5025–5040.

Fulponi, L. (2007). The globalization of private standards and the agri-food system. In J. Swinnen (Ed.), Global supply chains, standards and the poor (pp. 5–18). Wallingford: CABI Publications.

Hoekstra, A., & Chapagain, A. (2008). Globalization of water: Sharing the planet”s freshwater resources. Blackwell Publishing.

Hoogesteger, J., & Wester, P. (2015). Intensive groundwater use and (in)equity: Processes and governance challenges. Environmental Science & Policy, 51, 117–124.

Kounina, A., Margni, M., Bayart, J., Boulay, M., Berger, Bulle, C., et al. (2013). Review of methods addressing freshwater use in life cycle inventory and impact assessment. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 18(3), 707–721.

Mehta, L., Veldwisch, G. J., & Franco, J. (2012). Introduction to the special issue: Water grabbing? Focus on the (re)appropriation of finite water resources. Water Alternatives, 5(2), 193–207.

Ochoa, E. (2006). Canadian mining operations in Mexico. In L. North, et al. (Eds.), Community rights and corporate responsibility: Canadian mining and oil companies in Latin America (pp. 143–160). Toronto: Between the Lines.

Oré, M. T., Del Castillo, L., Laureano, Orsel, S., & Vos, J. (2009). El agua, ante nuevos desafíos. Actores e iniciativas en Ecuador, Perú y Bolivia. Lima, Perú: IEP; Oxfam International.

Ramirez-Vallejo, J., & Rogers, P. (2010). Failure of the virtual water argument: Possible explanations using the case study of Mexico and NAFTA. In C. Ringler, A. K. Biswas, & S. A. Cline (Eds.), Global change: Impacts on water and food security (Chap. 6). Berlin: Springer.

Ridoutt, B., & Pfitser, S. (2010). A revised approach to water footprinting to make transparent the impacts of consumption and production on global freshwater scarcity. Global Environmental Change, 20, 113–120.

Roth, D., & Warner, J. (2008). Virtual water: Virtuous virtual impact? Agriculture and Human Values, 25, 257–270.

Smaller, C., & Mann, H. (2009). A thirst for distant lands: Foreign investment in agricultural land and water. Winnipeg: IISD.

Sojamo, S., Keulertz, M., Warner, J., & Allan, J. A. (2012). Virtual water hegemony: The role of agribusuness in global water governance. Water International, 37(2), 169–182.

Solanes, M., & Jouravlev, A. (2007). Revisiting privatization, foreign investment, international arbitration, and water. Santiago: UN/ECLAC.

Stoltenborg, D., & Boelens, R. (2016). Disputes over land and water rights in gold mining. The case of Cerro de San Pedro, Mexico. Water International, 41(3), 447–467.

Sultana, F., & Loftus, A. (2012). The right to water: Politics governance and social struggles. Earthscan, Routledge: London and NY.

Swyngedouw, E. (2005). Dispossessing H2O: The contested terrain of water privatization. Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, 16(1), 81–98.

Swyngedouw, E. (2013). Into the sea: Desalination as hydro-social fix in Spain. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 103(2), 261–270.

Swyngedouw, E. (2014). “Not A Drop of Water…”: State, modernity and the production of nature in Spain, 1898–2010. Environment and History, 20, 67–92.

Urkidi, L. (2010). A glocal environmental movement against gold mining: Pascua-Lama in Chile. Ecological Economics, 70, 219–227.

Urteaga, P. (2013). Entre la abundancia y la escasez de agua: discursos, poder y biocombustibles en Piura, Perú (Between water abundance and scarcity: the cultural politics of biofuels in Piura, Northern Peru). Debates en Sociologia, 38, 55–80.

USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, (2014) Peru Biofuels Annual 2014. GAIN Report: Washington.

van der Ploeg, J. D. (2008). The new peasantries. Struggles for autonomy and sustainability in an era of empire and globalization. London: Earthscan.

van der Ploeg, J. D. (2010). The food crisis, industrialized farming and the imperial regime. Journal of Agrarian Change, 10(1), 98–106.

Venot, J. P., & Clement, F. (2013). Justice in development? An analysis of water interventions in the rural South. Natural Resources Forum, 37, 19–30.

Vos, J. (Ed). (2010). Riego campesino en los Andes. Seguridad hídrica y seguridad alimentaria en Ecuador, Perú y Bolivia, IEP, Lima.

Vos, J., & Boelens, R. (2014). Sustainability standards and the water question. Development and Change, 45(2), 1–26.

Vos, J., & Hinojosa, L. (2016). Virtual water trade and the contestation of hydro-social territories. Water International, 41(1), 37–53.

Woodhouse, P. (2012). New investment, old challenges. Land deals and the water constraint in African agriculture. Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(3–4), 777–794.

Yacoub, C., Duarte, B., & Boelens, R. (Eds.). (2015). Despojo del Agua y Ecología Política. Hidroeléctricas, industrias extractivas y agro-exportación en Latino América. Quito: Abya-Yala.

Zoomers, A., & Kaag, M. (Eds.). (2013). Beyond the hype: A critical analysis of the global “land grab”. London: ZED.

Zwarteveen, M., & Boelens, R. (2014). Defining, researching and struggling for water justice: Some conceptual building blocks for research and action. Water International, 39(2), 143–158.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and any changes made are indicated.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work”s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work”s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2016 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Vos, J., Boelens, R. (2016). The Politics and Consequences of Virtual Water Export. In: Jackson, P., Spiess, W., Sultana, F. (eds) Eating, Drinking: Surviving. SpringerBriefs in Global Understanding . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-42468-2_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-42468-2_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-42467-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-42468-2

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)