Abstract

This Chapter concerns public perceptions about who should have access to scarce antiviral drugs and vaccines in a flu pandemic. Two methods of public engagement are compared and evaluated; namely a survey, and a deliberative forum. In undertaking public engagement, researchers and policy makers may be motivated by the desire to build policy which is acceptable and workable in the community, that is instrumental goals are foremost. With instrumental goals in mind, there are a number of ways to collect community views but they may provide quite different answers as shown in the two examples described here. In the chapter we explore, the relationship between choice of method of engagement and (i) the findings of the engagement exercise, and (ii) the acceptability and applicability of these findings in a policy context.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Limited resources linked to unlimited demand for health care means that ranking of competing demands, with associated funding decisions, is essential in any health care system. Such decisions may have social and political consequences: the former will impact the community directly and the latter will ensure that political attention is focussed on the area. Both may be used to justify the collection of community views with respect to allocation of scarce resources in a pandemic. However, some might argue that allocation of scarce resources in this scenario should be based solely on expert evaluation of evidence. That is, evidence should be used to prioritise the needs of sub-groups in the population and to evaluate the efficacy of specific health resources in addressing those needs. The objectives in resource allocation in a pandemic might include (i) maximising community benefit, (ii) equitable allocation of resources, (iii) protection of vulnerable groups, and (iv) fulfilment of obligations for reciprocity towards those who might put themselves at risk to provide care. Examining these objectives, it appears likely that interpretations of benefit, equity and the bounds of reciprocity will differ across the citizenry and that it will be important to consider community opinion and values in making these decisions.

In doing so we would address instrumental goals (Abelson et al. 2007): we would focus on collecting community views in order to build policy that better reflects community preferences and values and is therefore more acceptable and workable. However, community views might be elicited for other reasons such as to support democratic or process oriented goals (Abelson et al. 2007). This orientation, which values citizen involvement in decision-making for its own sake, emerges from a number of areas including deliberative democratic theory (Smith and Wales 2000), the rise of literate active citizen groups and the increased demands for public accountability for public funding. In this case the focus is on democratic decision-making, fair and transparent process and participant empowerment. Alternatively capacity building goals (Abelson et al. 2007) may focus attention on improving community health literacy and enhancing the ability for citizens to engage in debate in areas of complex health policy.

Surveys are a widely used method for meeting instrumental goals: to elicit public views to inform policy decision-making or to provide public commentary or response on past decisions. A legitimate concern in gauging community views in this way is that the level of knowledge in the community about some of the more complex areas of healthcare planning and policy may be low. This may be particularly the case with emerging health technologies, new health threats or complex health policy areas. This methodological weakness may also apply to qualitative methods such as focus groups or interviews. The concern is that the community perspective, accessed through any of these methods, prior to a projected health emergency such as a pandemic, or before a new technology is rolled out, may change when the emergency occurs or technology is used and there is more interest in and access to information. In addition, policymakers might question the validity of citizen-driven decisions when the citizens have limited access to information to adequately inform those decisions. For this reason, deliberative process has been proposed as an anticipatory tool which can gauge the views of the community in policy areas that may generate future issues but where there is little current public debate (Warren 2009). Deliberative methods involve prolonged engagement with community members and provision of detailed information which the participants may draw upon in their decision-making. However, these methods also suffer from drawbacks, in particular with respect to how representative the views presented in small forums are of the population at large. These issues may limit the acceptability of deliberative methods to policymakers seeking to use community views to inform policy decisions.

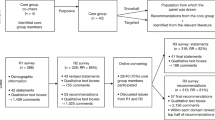

Which method should a policy maker use in collecting community views to inform policy and how will the choice of method affect the findings? Very few studies compare different methods for gauging public perspectives on a single issue. This chapter uses a case study to examine the relationship between the choice of goals and methods and the resultant outcomes. We compared community views in South Australia on the allocation of scarce resources in a pandemic using two different methods: first, a cross-sectional survey of nearly 2000 citizens using computer assisted telephone interviews; and second a deliberative inclusive forum which used stratified random sampling to select a small number of citizens. The first method offered a snapshot of community views in a policy area which, at the time before the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, was not topical and on which the general public was not well informed. The second method allowed for engagement with citizens in an informed deliberative process, also prior to the 2009 pandemic.

Pandemic Influenza as a Case Study

The importance of planning for a pandemic was reinforced by the emergence in 2009 of a novel influenza A (subtype H1N1) virus. National plans (Department of Health and Ageing 2008a), developed in response to an emergent virulent Avian Influenza A (H5N1) and the 2003 SARS outbreak, were implemented during the first wave of the 2009 pandemic. Prior to 2009, the Australian Commonwealth Government as part of its pandemic planning had stockpiled nearly 9 million courses of antiviral drugs (Department of Health and Ageing 2009a) which fortunately proved an effective treatment for pandemic-strain H1N1 viral infections. In addition, a specific vaccine against a candidate strain of H5N1 was developed (Department of Health and Ageing 2008b) and an agreement to develop and produce pandemic viral vaccines as required was contracted with a private company (Department of Health and Ageing 2009a). Therefore with the emergence of the novel H1N1 sub-type in March–April of 2009, the Australian Prime Minister was able to reassure the Australian public that it was “the best prepared country in the world to deal with the threat of swine flu” (The Daily Telegraph 2009). Ultimately Australia was the first country to develop, test and deliver a pandemic vaccine (Greenberg et al. 2009; Nolan et al. 2010).

Despite this preparation, gaps in pandemic planning persisted, some of which became apparent during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. The mildness of the virus caught policymakers by surprise and in Australia a new ‘protect’ phase (Department of Health and Ageing 2009b) was devised to cater to this turn of events. Planning had been primarily carried out with little consultation with stakeholders, such as healthcare personnel, who were involved in implementing the plans, or the public, who were impacted by the plans in their daily lives. Some key issues had been only sketched out. In particular, the groups allocated as priority for access to antiviral drugs and vaccine in pandemic had only notionally been described (Department of Health and Ageing 2008a). Even now it is not clear how decisions about allocation of scarce resources will be made should such resources be in short supply in a severe pandemic. Some of the gaps exposed in the 2009 pandemic were foreshadowed by the findings of the deliberative forums described later in the chapter.

Telephone Survey

A detailed description of the methods used for the telephone survey has been published elsewhere (Marshall et al. 2009). This was a cross-sectional study using a computer assisted telephone survey of 1975 citizens (participation rate 67.2 %) aged 18–94 with a mean age of 53 years. The participants were randomly selected from the South Australian electronic white pages telephone listings and the interviews conducted in April–May, 2007. This survey was part of the Health Monitor program through HealthSA. The survey was 15 min long and consisted of 36 questions.

The study was conducted to assess both knowledge of pandemic influenza (PI) and community attitudes towards the proposed implementation of strategies such as home isolation and vaccination to prevent spread of infection. Open-ended questions were asked where possible. The survey data were weighted to the age, gender, and geographical area profile of the population of South Australia and the probability of selection within a household. Participants were asked the meaning of ‘pandemic influenza’ and following this question a comment to explain PI was included:

An influenza pandemic occurs when a new influenza virus appears and the human population has no or poor immunity to the new virus. This causes a rapid spread of the virus to people around the world and has the potential to cause large numbers of deaths and serious illness.

No other information was provided. Two of the questions posed to the participants were:

If supplies of the vaccine were limited who would you consider a priority for vaccination?

Do you believe enough is being done to prepare for a pandemic?

Participants were not provided with any prompts and the responses were self nominated. Data was analysed using Stata with routines specifically designed to analyse clustered weighted survey data (Stata 2005). Statistical tests were 2-tailed with a significance level of 5 %. The study was approved by the Children, Youth and Women’s Health Service research ethics committee.

Deliberative Forum

A deliberative forum, in the style of a citizens’ jury, was convened in Adelaide, over one day, in February 2008. The forum deliberated on the question:

Who should be given the scarce antiviral drugs and vaccine in an influenza pandemic?

A detailed description of the methods used in this research have been published elsewhere (Rogers et al. 2009; Braunack-Mayer et al. 2010).

The research was guided by a reference group of policymakers and academics from communicable disease control, epidemiology, health promotion, public health economics, health ethics and public policymaking. Participants were recruited by the same market research company as for the survey, from a database of citizens, recruited through an annual face-to-face community survey.Footnote 1 Potential forum members (N = 14) were selected using random sampling stratified with respect to gender, age, employment and household income. Withdrawal of five of the participants, at late notice, meant that the forum, with 9 participants, was older and more female than anticipated. All participants attended a pre-forum evening dinner and received an honorarium of $100 and travel expenses.

Information Modules

Evidence concerning the efficacy and effectiveness of antiviral drugs and vaccines in the event of an influenza pandemic was collected from a systematic review of the peer-reviewed and grey literature. Information modules were prepared in simple language in relevant areas such as evidence for safety, effectiveness and efficacy of vaccines and antiviral drugs, and the ethical and logistical issues associated with provision of vaccine and antiviral drugs at a population level in a pandemic.

Forum Process and Structure

Participants were seated around a single rectangular table. Specialist experts sat at the table when delivering information, otherwise they sat at the back of the room. Material was recorded on an electronic whiteboard and deliberations were recorded using immediate transcription with backup voice recording.

The day, which was guided by an independent facilitator, allowed the jury to interact with specialist witnesses. The forum worked as individuals, small groups and as a whole to deliberate the question and deliver their verdict. Forum members were advised that they were seen as experts in relation to their own experience and as citizen representatives.

Assumptions Made by the Forum

The jurors were told that there were initial reserves of antiviral drugs and vaccines (when made available) to treat only 10 % of the population or provide preventive prophylaxis for 5 %. The forum understood that antiviral drugs would initially be provided to ill persons and their contacts in an effort to contain the pandemic. It was assumed that the period of containment had passed rapidly so that a significant drug stockpile remained. It was assumed that the vaccine would not be available for 3–6 months after the recognition of a new pandemic virus. The forum also assumed that unlike the first wave of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza, the virus would be highly virulent and cause large numbers of cases and a high clinical case-fatality rate.

Findings from the forum included flip chart and electronic whiteboard recordings from small group and summary sessions and the anonymised transcripts from the deliberation. Evaluation of the forum was carried out through a telephone survey of all participants which asked them about their views on process and outcomes. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Adelaide.

Findings

Survey

The South Australian survey respondents were asked for their opinion on whom should be immunised first using the scarce vaccine supplies in a pandemic. Of the respondents canvassed by the telephone survey, most placed children (49.7 %; CI: 47.0–52.3) or the elderly (23.3 %; CI: 21.2–25.7) at the top of the priority list (see Table 12.1).

A gender difference in this response was observed (χ2 = 25.1 P < .001) with men more supportive of emergency service workers (i.e. ambulance, emergency management, fire and rescue services) receiving priority for vaccination (63.0 %; 95 % CI: 56.1, 69.4) than women (37.0 %; 95 % CI: 30.6, 43.8). Women were more likely to consider vulnerable groups such as children, the elderly, or sick people as priorities for vaccination (53.9 %; 95 % CI: 50.9, 56.9) than were men (46.1 %; 95 % CI: 43.1, 49.1).

Vaccine and antiviral drug production workers, workers in essential services such as electricity or water supply and the military did not feature in the list compiled from survey respondents. Health care workers such as hospital workers and doctors, made the top of the priority list for 10.7 % of the survey respondents.

Less than a third 32 % (95 % CI: 29.5, 34.6) of the survey participants believed that enough was being done to prepare for a pandemic with nearly half 44.7 % (95 % CI: 42.1, 47.4) unsure.

Deliberative Forum

The initial list of potential recipients identified by the forum was broad and eclectic and included groups providing services in high demand in a pandemic such as health care workers and funeral organisations, groups that were essential to the continued maintenance of societal function such as water and electricity workers and vulnerable populations such as asylum seekers and prisoners. Several participants included people aged 2–30 years for a number of reasons: they were seen as an important conduit for influenza transmission, as important for the survival of society and as a vulnerable population group.

The constraints of the limited stockpiles were quickly reached and the forum discarded specific vulnerable groups from their final list (see Table 12.2) in favour of groups that would be necessary to maintain medical services, vaccine and antiviral drug development and production, and essential services. They removed groups such as the clergy and funeral organisations whose roles might potentially be covered by others in the population but included the military because of their multi-skilled workforce trained in disaster and emergency response.

In prioritising the list, the forum participants focussed on preservation of society in a time of crisis. Although the questions were posed separately, most of the participants did not distinguish between antiviral drugs and vaccine and felt distribution patterns should be similar for both.

If forced to choose between preserving society in the long run and saving the most lives the forum indicated that it would choose to preserve society. In particular, the forum wished to uphold the Australian life style and ensure personal independent living through continued access to essential services.

The South Australian forum participants were aware of the potential in a severe influenza pandemic for loss of essential services such as sewage, water and power and that health services would be under severe stress. The potential impact on society of such circumstances became apparent in the deliberative process. The forum participants were also aware of the value of vaccine development and continued production of antiviral drugs. Their response was to prioritise workers in these areas. The most surprising choice of the forum was to include the military in the priority list. However, this is explicable in the light of the forum’s aim to support and preserve society in potentially catastrophic conditions, and when it is placed in the context of Australian experiences with the role of the Australian military. In recent years, the Australian military has been involved in a number of humanitarian and international policing roles including the public health and medical response to the 2004 Aceh Tsunami (Pearce et al. 2006), a policing role in the 2003 Australian-led Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (Hegarty 2001) and nation building in East Timor (Blaxland 2002). The forum saw the military as a flexible resource, able to provide an effective response in a time of extreme stress.

Discussion

These two studies suggest that asking the community their views on an issue of allocation of scarce resources with different methods may provide very different answers to the same question. It is clear that the forum participants placed greater importance on the preservation of society and societal functions and expressed less concern about protection of specific vulnerable groups. In contrast, the survey participants emphasised vulnerable populations, particularly the elderly and the young. In this discussion we will examine how the characteristics of the two methods might have affected findings in each case. We will also explore how the choice of method might impact the acceptability and applicability of the findings in the policy context. Finally, we will compare the findings from the studies described in this paper with similar studies carried out elsewhere.

Method Characteristics Which Affected Participant Decision-Making

Level of Understanding

Although we do not know how much consideration individual survey participants gave to the question, we do know that the level of knowledge of pandemic influenza shown by many of the survey respondents was low. It would therefore be reasonable to suppose that the decision-making of this group, as a group, was less informed than in the forum and, for many survey participants, was based on the minimal information provided during the survey. The forum clearly had an advantage over the survey in terms of resources available to support decision-making since participants had access to written and verbal information, were able to actively question expert witnesses in real time and had access to material resources such as whiteboards to assist collective decision-making.

Opportunity to Consider the Options

The survey participants lacked not only the information available to the forum participants but also the opportunity to discuss their opinions with others, to weigh the advantages and disadvantages of different choices, and to engage in a structured decision-making process. A structured decision-making process and transcription of the deliberation with subsequent analysis, such as occurred in the deliberative forum, permits documentation of the decision-making process and the underlying reasons for the decisions. The underlying reasons for the participants’ choices were not explored in the survey but the attitudes described may reflect Australian public health messages about which population subgroups would benefit most from the seasonal influenza vaccination (Fiore and Neuzil 2009). It is possible that these messages influenced survey participants in their choices. Alternatively the choice may reflect consideration of and concern for vulnerable groups in society more generally.

Timing of Community Involvement

Given that political context and timing may be important influences on public response, it is worth noting that the two data collection processes described were held in the same state of Australia during a similar time period when interest in pandemic influenza was low and the level of transparency of government decision-making in the area could be considered low to moderate. That is, the data collection in both cases occurred early in the decision-making process at a ‘stage when value judgments might be important’ (Rowe and Frewer 2000, 14). This may influence the response in that survey participants may perceive the question to be of little interest and not applicable personally to them. Such a response may change if the question was asked during a severe pandemic. In contrast, in the deliberative forum the participants were guided through the events which would unfold in a pandemic and therefore were more immersed in the scenario. It is still possible that they did not perceive that they would be personally affected but it is much less likely and the responses from the participants in the forum suggested that they did see themselves to be at risk. For example, participants in discussing whether scarce antiviral drugs should be reserved for essential services, related their judgment back to their own personal risk in the circumstances.

-

Participant 1: Not so much. I wouldn’t pick the essential services people because they are at risk, I would pick them because without power, water what have you, society wouldn’t function.

-

Participant 2: We would be at more risk. They are the things that make our living go on in sickness and health.

Method Characteristics Which Affected Acceptability to Policymakers

Representativeness

Both methods of community engagement described in this chapter randomly selected participants to fill categories so that the groups reflected population demographics. However a forum of nine people is obviously not statistically representative whereas the survey did include sufficient randomly selected participants to fulfil this criterion. The forum could be considered to be ‘logically’ representative in that one can use some process of logical deduction to draw conclusions from the forum. If we use the analogy of decision-making in the courts, and are willing to accept a court decision made by a jury of 12 members of the community as binding, we could argue that the forum is ‘representative’ but we would also have to accept that another jury or another forum may make a different decision. Unlike a court jury or the survey findings, the deliberative forum provided a rationale for their decision and therefore, as ‘observers’ we are able to examine that decision-making and decide if we think the rationale is acceptable and therefore representative of our own possible decision under similar circumstances. The findings of the deliberative forum described in this exercise were not widely broadcast but, if this did occur, public discussion could be elicited through print and on-line media such that the ‘representative’ nature of the findings could be tested in the public arena.

Smith and Wales (2000) suggest that when community involvement is limited to such a small number, inclusiveness and not representativeness should be the criteria of analysis, since such a small sample could never “accurately mirror all the standpoints and views present in the wider community” (Smith and Wales 2000, 56). That is, the participants are not chosen to represent categories of society but rather so that the forum might be inclusive of a range of experience and perspective to be found in the community (Street et al. 2014).

Generalisability

Similarly if we are willing to accept a court decision made by a jury of 12 members of the community as binding and, through this, generalisable to other situations, then we can similarly regard our forum as generalisable. However, if we treat the deliberative forum as a data collection and analysis exercise that merely informs policymaking, then generalisability is a more difficult issue. The best that we can say is that a deliberative forum tells us about how an informed and engaged public might interpret and make decisions about a particular issue. Thus, if the methods adopted with the forum were used in a publicity campaign aimed at the general population, then public acceptance of the allocation choices would possibly be similar. Without such a campaign the outcomes of the forum may be of little value since an uninformed public could allocate the resources differently. The survey on the other hand could be considered to be generalisable to the South Australian population as a whole at least at the collection time point.

Transparency and Rigour

Both forum and survey were conducted independent of external influence from a sponsoring organisation, although in the case of the forum, representatives of the funding partners (South Australian Department of Health) sat on the reference group. Participants in both had full control over their choices as to who should be considered a priority for receiving scarce drug supplies in a pandemic.

Transparency in community engagement, as described by Rowe and Frewer (2000), should be such that the broader public can judge the independence and validity of the engagement process. Transparency, in this context, was low for both methods, since details about the participation process, and the subsequent findings in each case, were not revealed, except in the academic literature following a peer review process and journal publication. The peer review process does permit explicit judgment of independence and validity and in this context both methods could be considered to have high transparency. Dissemination without peer review is generally discouraged in academic circles, but this approach runs contrary to deliberative democratic theory which suggests that details about the forums should be publicised at all steps in the process. Suppression of details about the forum, until a publication had passed muster at peer review, was endorsed by the policy partners but it could be criticised, in that, such an approach prevents broader public engagement and debate which might be expected to ensue if engagement exercises were more broadly advertised.

Cost

A costing for the two methods (2008 figures) is shown in Tables 12.3a and 12.3b. Costs will vary depending on the facilities available to the researchers and the level of amenities used but the deliberative forum was clearly considerably more expensive than the survey. However, if the evidence collected for the forum had been otherwise available (for example, already collated for another purpose) the cost would be similar to that of a survey.

Theoretical Frameworks

The two methods used in this example are drawn from very different theoretical frameworks. Surveys arise from a positivist understanding of the world where social phenomena can be measured and categorised and where meanings are not problematic. Surveys can provide useful descriptive data which cannot be efficiently collected by any other method. Deliberative forums, in contrast emerge from deliberative democratic theory which contends the transformative nature of informed debate and argument in decision-making. In this framework, new meanings may be constructed in the space between the evidence presented and the experience of the citizen participants. However, the deliberative forum described in this chapter took place in a team project negotiated between academic researchers and policymakers. Some members of the team approached the project from a constructivist framework with capacity building and/or democratic empowerment goals foremost whereas some worked from a positivist framework and focussed solely on instrumental goals. The constraints of time and money meant that not all these goals could be met: choices were made which compromised democratic process in order to deliver outcomes which would be most useful for policymaking.

Outcomes

Influence in the Policy Sphere

The deliberative forums took place while pandemic plans were still undergoing review, thereby allowing feedback of the outcomes to policymakers: policymakers sat on the steering committee; the findings were provided to the state Pandemic Influenza Health Steering Committee on a regular basis; and a summary of the findings were submitted to the Pandemic Influenza Sub-committee of the Coalition of Australian Governments (COAG). No explicit effort was made to feedback the findings of the survey to policymakers but the findings were reported at the annual National Immunisation Conference (as were the findings of the deliberative forum) which is attended by policymakers working in the infectious disease area. However, we do not know what effect, if any, the findings of the forum or the survey had on policy development.

Comparing the Two Methods with Other Data Collection Exercises

In comparing the outcomes from these two methods with the limited number of community engagement exercises on the same question in other countries, research method appears to be a major contributor to differences in the findings. The choices made by the deliberative forum are similar to those made by participants in another deliberative engagement exercise, the Public Engagement Pilot Project on Pandemic Influenza (PEPPPI) project (HHS USA 2005), which was staged in four states in the United States (see Table 12.4). Participants in the PEPPPI project supported the goal of ‘assuring the functioning of society as first priority in provision of vaccine’, followed by ‘reducing the individual death and hospitalization due to influenza’. The other possible options: ‘prioritise young people’, ‘use a lottery system’ or a ‘first come first served’ approach had little support. A similar exercise in Canada (Pan-Canadian Public Health Network 2007) on the allocation of antiviral stockpiles also supported the goal of “keeping society functioning” over “minimize serious illness and death”. Support for “minimize government’s role” with highest priority given to health care workers was not because they were at greater risk (although for some participants this was a factor) but because they played an important role in “keeping society functioning and containing the spread”. This is similar to the findings of the forum described in this chapter.

Participants in a large survey in Ireland (Irish Council of Bioethics 2006), ranked health care workers as first priority (Table 12.1) which on the surface seems to be more similar to the finding of the deliberative forum than the South Australian survey. Second choice was the elderly and children. However, when the Irish citizens were asked the reason for their choice most chose “treat everyone equally as possible” (43 %) over “give priority to sick and frail” (27 %) or “save the most lives” (23 %) (Irish Council of Bioethics 2006). Only 5 % of the Irish respondents selected “preserve essential services” as their top priority. This suggests their choice of health care workers was to permit continued treatment of all, including the survey participants themselves, rather than preservation of the structure of society. This places the outcomes of the Irish survey more in keeping with the South Australian survey, which also did not envisage that a pandemic might pose a threat to social function, in contrast to both the PEPPPI project and the South Australian forum which did.

What Did the Findings Add to the Policymaking Process?

The South Australian forum priorities fit closely with Australian Government priorities listed in the Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza (AHMPPI) (Department of Health and Ageing 2008a) for a severe pandemic: the AHMPPI would prioritise pre- and post prophylaxis for health care workers and some other occupational groups but also includes ‘treatment of cases as clinically appropriate’. This might include the survey participants’ choice of the young or the elderly if these groups were found to be particularly vulnerable to a specific strain but the plan does not include these groups without such a proviso. In a severe pandemic the AHMPPI contains provision for ‘the need to maintain functioning of critical infrastructure’ which fits closely with the choices of the South Australian forum.

A study by Uscher-Pines et al. (2006) which looked at national preparedness plans around the globe found that essential service workers and health care workers were the second and third most prioritised groups with the armed forces seventh and vaccine manufacturers tenth. The most prioritised group in national preparedness plans is high risk individuals, who did not feature on the lists from either the South Australian survey or the deliberative forum. The highest priority groups in the South Australian survey, the elderly and children, are fourth and fifth of the most prioritised groups globally.

Both methods are important for policymakers since the survey provided an indication of the degree of understanding in the population and the way in which a variably informed public may view decisions about resource allocation in a pandemic. In contrast, the forum provided informed community perspectives and highlighted areas in which citizens can contribute to our understanding of the values which citizens may hold in a situation of resource allocation in an emergency. It is noteworthy that a well-informed public, as represented by the forum, might be more likely to accept resource allocation as described in the AHMPPI, compared to a public who have been shielded from discussion about worst case scenarios. In this case study of pandemic planning in a pre-pandemic era, both of these methods proved valuable by providing insight into community understanding and values for decision-making about scarce antiviral drugs and vaccine. Using a variety of methods to engage the public may help to shape more effective and efficient policy and practice.

Using Participatory Methods for Policymaking

The deliberative forum described in this study differed from citizens’ jury models which focus on capacity building or democratic goals: the citizens were not involved in the development of the materials or the selection of the witnesses; the forum was smaller and there was a tight time frame. These modifications were in response to our instrumental goals which focussed on the best way to collect views about allocation of scarce pharmaceuticals in a pandemic such that these views reflected an informed public opinion which might be used to inform policymaking. Within a limited budget, we wished to gauge community perspectives on a number of different aspects of the Australian Pandemic Influenza Management plan and were therefore constrained with respect to time and funding available to explore each area.

In addition, although our evaluation suggested that individuals participating in the forum felt empowered by their participation, our primary objective in conducting the exercise was not to fulfil the democratic goals of empowerment and citizen participation but rather the instrumental goals of health technology assessment and informing policy (Abelson et al. 2007). Both the survey and the forum fulfil the objective of community consultation but provide different information about community perspectives. This clear difference in outcomes raises concerns about the danger in policy development of ‘cherry-picking’ preferred results through the selection of methods which will provide those results.

It is worth noting that, although we presented the participants in our forum with a comprehensive summary of the relevant information from the published literature, some information available to policymakers may not be in the public realm and therefore the information used in deliberative methods may be incomplete. This may impact on the quality of the decision-making. Similarly some information will be dependent on the nature of the pandemic virus and therefore information can never be complete in a pre-pandemic period and as has been shown with the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, uncertainty may persist well into the pandemic period (Roxon 2009).

Conclusion

These studies support the view that although surveys may elicit wide acceptance from the public and policymakers because of high representativeness, the quality of the decisions elicited is compromised by the inability of most citizens to access crucial information which would be readily available to a government decision-maker. Deliberative forums potentially provide higher quality information about decision-making but may struggle for acceptance by policymakers and politicians because of the small number of participants, with concerns about generalisability of the results. Our work would support the contention of Rowe and Frewer (2000) that a combination of several methods with different strengths can provide a more complete picture of community views and therefore a solid base on which to build effective policy.

Notes

- 1.

Participants in the South Australian Health Omnibus Survey (HOS) are aged over 15 and are selected using a random pattern of street addresses across a random pattern of suburbs and are weighted by age, gender and geographic location to accurately reflect the South Australian population. First contact is by letter with an opt-out clause. The HOS had a 70 % participation rate.

References

Abelson, J., M. Giacomini, P. Lehoux, and F. Gauvin. 2007. Bringing ‘the public’ into health technology assessment and coverage policy decisions: From principles to practice. Health Policy 82(1): 37–50.

Blaxland, J. 2002. Information-Era Manoeuvre: The Australian-Led Mission to East Timor. Journal of Information Warfare 1(3): 94–106.

Braunack-Mayer, A.J., J.M. Street, W.A. Rogers, et al. 2010. Including the public in pandemic planning: A deliberative approach. BMC Public Health 10: 501.

Department of Health and Ageing. 2008a. Australian health management plan for pandemic influenza. Canberra: Australian Government.

Department of Health and Ageing. 2008b. Media release: Securing the nation against potential threats. Canberra:Australian Government.

Department of Health and Ageing. 2009a. Media release: Federal government adds more antivirals to National Medicines Stockpile. Canberra: Australian Government.

Department of Health and Ageing. 2009b. New pandemic phase protect, Canberra: Australian Government. 17th June. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/healthemergency/publishing.nsf/Content/news-170609. Accessed 12 Apr 2010.

Fiore, A.E., and K.M. Neuzil. 2009. Influenza a(H1N1) monovalent vaccines for children. The Journal of the American Medical Association 303(1): 73–74.

Greenberg, M.E., M.H. Lai, et al. 2009. Response to a monovalent 2009 influenza a (H1N1) vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 361: 2405–2413.

Health and Human Services (HHS USA). 2005. Citizen voices on pandemic flu choices: A report of the public engagement pilot project on Pandemic Influenza. ppc.unl.edu/documents/PEPPPI_FINAL REPORT _DEC_ 2005 .pdf. Accessed 6 Sept 2011.

Hegarty, D. 2001. Monitoring peace in Solomon Islands. SSGM Working Paper 01/4. In State Society and Governance in Melanesia Project. RSPAS, Canberra: Australian National University.

Irish Council of Bioethics. 2006. Ethical Dilemmas in a Pandemic: Results of the ICB/TNS MRBI Survey. In Proceedings of the Irish Council for bioethics conference. Dublin. www.bioethics.ie/uploads/docs/PandemicProceedings.pdf. Accessed 6 Sept 2011.

Marshall, H., P. Ryan, D. Roberton, J. Street, and M. Watson. 2009. Pandemic influenza: Community preparedness? American Journal of Public Health 99(S2): S365–S371.

Nolan, T., J. McVernon, M. Skeljo, et al. 2010. Immunogenicity of a monovalent influenza a (H1N1) 2009 vaccine in infants and children – A randomized trial. The Journal of the American Medical Association 303(1): 73–74.

Pan-Canadian Public Health Network. June 2007. Annex 3.7-Report on citizen and stakeholder deliberative dialogues on the use of antivirals for prophylaxis. Pan-Canadian public health network council report and policy recommendations on the use of antivirals for prophylaxis during an influenza pandemic. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/2008/prapip-uappi/index-eng.php. Accessed 6 Sept 2011.

Pearce, A., P. Mark, N. Gray, and C. Curry. 2006. Responding to the Boxing Day tsunami disaster in Aceh, Indonesia: Western and South Australian contributions. Emergency Medicine Australasia 18: 86–92.

Rogers, W., J.M. Street, A.J. Braunack-Mayer, J.E. Hiller, and the FluViews Team. 2009. Pandemic influenza communication: Views from a deliberative forum. Health Expectations 12(3): 331–342.

Rowe, G., and L.J. Frewer. 2000. Public participation methods: A framework for evaluation. Science, Technology and Human Value 25(1): 3–29.

Roxon, N. 2009. Transcript of press conference with Hon. Nicola Roxon MP, Australian Minister for Health and Ageing, 22 July. http://www.rcna.org.au/LiteratureRetrieve.aspx?ID=50173&A=SearchResult&SearchID=1273333&ObjectID=50173&ObjectType=6. Accessed 11 Apr 2010.

Smith, G., and C. Wales. 2000. Citizens’ juries and deliberative democracy. Political Studies 48: 51–65.

StataCorp. 2005. Stata statistical software: Release 9. College Station: StataCorp LP.

Street, J., K. Duszynski, S. Krawczyk, and A. Braunack-Mayer. 2014. The use of citizens’ juries in health policy decision-making: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine 109: 1–9.

The Daily Telegraph, 11 June 2009. WHO points to Australian cases over swine flu pandemic. http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/classmate/who-points-to-australian-cases-over-swine-flu-pandemic/story-e6frewti-1225732672797. Accessed 6 Sept 2011.

Uscher-Pines, L., S.B. Omer, D.J. Barnett, et al. 2006. Priority setting for pandemic influenza: An analysis of national preparedness plans. PLoS Medicine 3(10): e436.

Warren, M.E. 2009. Two trust based uses of minipublics in democracy. In Democracy and the deliberative society conference. University of York.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge additional members of the FluViews team: Janet Hiller, Rod Givney, Christine Andrews, Peng Bi, Ann Koehler and Heather Petty. Our partner in this research was the South Australian Department of Health, whose support we appreciate. Funding was provided by the Australian Research Council via its Linkage Grant program (LP 0775341).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Street, J.M., Marshall, H., Braunack-Mayer, A.J., Rogers, W.A., Ryan, P., FluViews Team. (2016). Seeking Community Views on Allocation of Scarce Resources in a Pandemic in Australia: Two Methods, Two Answers. In: Dodds, S., Ankeny, R. (eds) Big Picture Bioethics: Developing Democratic Policy in Contested Domains. The International Library of Ethics, Law and Technology, vol 16. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32240-7_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32240-7_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-32239-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-32240-7

eBook Packages: Religion and PhilosophyPhilosophy and Religion (R0)