Abstract

Today’s patterns of migration move on a continuum from long-term and permanent to increasingly temporary and fluid. In this context, it is central to understand immigrants’ intentions with respect to naturalization and remigration, not least because these intentions summarize the respondent’s attitude towards the migration experience. Using data from the Migration-Mobility Survey, this chapter tests in a multinomial logistic regression the effect of four sets of factors (demographics, transnational ties, feasibility, and integration) on four types of intentions: naturalization, settlement, remigration, and naturalization and remigration in conjunction. The results show that 34% of the recently arrived migrants in Switzerland express naturalization intentions, 34% settlement intentions and 26% remigration intentions. Although the first two types are largely explained by social integration, remigration intentions are determined by a weak labour market and social integration. However, the relationship between the level of integration and immigrants’ intentions is more complex because for 6% of the sample, both remigration and naturalization present an option. Finally, the chapter emphasizes how a high educational attainment fosters the migrant’s agency to choose whatever migratory trajectory they desire to follow, despite the more restrictive migration regime that Switzerland has introduced for non-EU/EFTA nationals.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

As presented Chap. 1 on the Migration-Mobility Nexus, migration patterns and regimes have undergone considerable transformations in recent decades in Europe, particularly in Switzerland. Today’s patterns of migration move on a continuum from long-term and permanent to increasingly more temporary and fluid. The situation is in part due to the establishment of the dual admission regime, with free movement of people applicable to the nationals of the EU/EFTA member states but with other rules for controlling the entry, admission and stays of third-country nationals. However, the increasingly international labour market has also given rise to a new, highly mobile class of young professionals and students – the so-called Eurostars (Favell 2008) –, that profit from these new opportunities. However, the country of destination has few means to prevent their re-emigration (Ette et al. 2016).

Although it is today central to study (highly) mobile immigrants, it is also important to consider other (less mobile) groups of migrants. This point applies in particular to “highly skilled migrants, who live permanently in their host countries” (Harvey 2009). For instance, 64% of EU15 movers were returning migrants (Favell and Recchi 2009). Although this number appears quite high, it suggests that among EU15 migrants, one of three settled more permanently in the host society. Swiss statistics draw a similar picture.Footnote 1 Of the immigrants who arrived in Switzerland in 1998, the proportion of those who had left the country after 17 years is 49%. This proportion is extremely high (over 80%) for American citizens, intermediate for EU citizens (62% for Germans and French, 54% for Italians and 34% for Portuguese), and lowest (less than 10%) for those from countries of former Yugoslavia and Sri Lanka.

Studying less-mobile groups is of further importance because foreign nationals who remain in the destination country might eventually apply for and receive citizenship, thus giving them the opportunity to contribute much more sustainably to the destination country’s society. When considering the same immigrant cohort of 1998 in Switzerland as mentioned above, 42% of the stayers had obtained Swiss citizenship after 17 years of residence.Footnote 2 Again, there are important variations in naturalization patterns, depending upon the country of origin. Immigrants from non-EU/EFTA countries were much more likely to be naturalized than were other nationals: While for example less than 10% of Portuguese nationals obtained Swiss citizenship, one third of individuals from the main immigrant countries (France, Germany, Italy) and two-thirds of immigrants from India were naturalized.

The Swiss legislation proposes two different naturalization regimes. Foreigners who have resided for 12 years in Switzerland can apply for ordinary naturalization,Footnote 3 whereas foreign spouses of Swiss nationals can apply for facilitated naturalization after 3 years of marriage, provided they have lived in Switzerland for a total of 5 years.Footnote 4 In 2016, on average, 78% of all 43,000 naturalizations fell into the first regime and 22% into the second regime (Loretan and Wanner 2017).

As emphasized by van Dalen and Henkens (2013, p. 1), “In the current era of globalization, understanding the decisions behind international migration is of increasing importance”. Research on future migratory projects – be it remigration, settlement or naturalization – will rely on either the revealed-preferences approach or the stated-preference approach. While the former focusses on actual behaviour, the latter, primarily used by social demographers, geographers and psychologists, privileges the understanding of the intentions to migrate or to settle.

Research has in fact shown that intentions can constitute a good predictor of future behaviour (e.g., De Jong 2000; van Dalen and Henkens 2008; Armitage and Conner 2001). However, some authors claim that emigration intentions do not qualify as a good predictor. In fact, social, economic and political constraints can prevent the actual return (Snel et al. 2015), and short-term stays can be prolonged or long-term stays can be interrupted (Engler et al. 2015), as shown by the “myth of return” of many former guest workers (Snel et al. 2015).

Nevertheless, the principal aim of the stated-preference approach is not necessarily to measure future migration behaviour. The approach shows the position of migrants on the continuum of remigration-settlement-naturalization intentions and therefore summarizes the respondent’s attitude towards the migration experience. Not least, immigrants’ intentions can affect behaviour such as investments in social contacts and skills (de Haas and Fokkema 2011; Carling and Pettersen 2014). Nevertheless, and in contrast to remigration intentions, the decision to naturalize is not only a rational individual choice but also subject to the destination country’s legal provisions and administrative practices.

Thus, this chapter aims at understanding the factors that trigger remigration and/or naturalization intentions in a high-income country setting. Using data from the Migration-Mobility Survey, we consider four types of intentions: naturalization intentions, settlement intentions (neither naturalization nor remigration intentions), remigration intentions, and naturalization and remigration intentions in conjunction. Although settlement and remigration intentions are often studied, naturalization intentions are les considered in the international literature. To the author’s knowledge, no paper has thus far investigated migratory projects in which both naturalization and remigration intentions are held in conjunction. Finally, we test in a multinomial logistic regression the effect of several explanatory factors that can be categorized into four groups – demographics, transnationalities, feasibility and preparedness, and integration in the host country – on the four types of intentions.

Section 12.2 presents the framework of this chapter by discussing the conceptual and theoretical considerations, the factors that were found in other studies to be determinant in explaining naturalization or remigration intentions, the main research question of the paper and the hypotheses. We then describe in Sect. 12.3 the data and methods that we used in this article. Section 12.4 presents and discusses the results of the descriptive findings and the regression analysis. A conclusion completes the chapter.

2 Remigration and Naturalization Intentions

A similar version of the literature review on remigration intentions will be published in Steiner (2018).

When studying stated migration preferences, divergent concepts are applied: the intention, the plans, the willingness, and the wish. The operationalization of each of these concepts is crucial to avoid misunderstanding when interpreting the results. For instance, the psychological and behavioural consequences of a “wish” are quite different from those of a “plan” (Kley 2011). Moreover, expressing a wish, desire or the willingness to move involves far less consideration of feasibility than expressing intentions to move, making plans, or having expectations (Lu 2011). Steiner (2018) showed for example that remigration intentions are explained by wishful thinking or a feeling of longing to live elsewhere. Planning an emigration in contrast is the result of concrete events, facts and opportunity differentials between the resident country and possible future destination country. Due to data availability, we will focus on the consideration and intentions to remigrate and/or naturalize rather than on the plan.

2.1 Conceptual and Theoretical Considerations

Although the literature on remigration intentions has considerably increased in recent years, naturalization intentions are rarely studied. Moreover, remigration and naturalization intentions are mostly considered separately. Two exceptions can however be mentioned: Leibold (2006) and Massey and Akresh (2006). The lack of literature is a paradox because remigration and naturalization can be seen as the opposite cornerstones of integration into the receiving society. Massey and Akresh (2006) showed for example that the plan to become a citizen and out-migration intentions are negatively correlated.

In line with neo-classical migration theory, which understands the decision to migrate as a rational individual choice, economically successful migrants settle permanently in the destination country, whereas emigration is a sign of “failed migration” (Constant and Massey 2002). This line of thought can also be applied to socio-cultural integration or the classical immigrant assimilation theory and to emigration, in which well-integrated migrants settle permanently in the host country.Footnote 5 Socio-cultural integration refers to the “identification with the home country, social contacts with native citizens, participation in social institutions of the host country and speaking the language” (Snel et al. 2015) and is often approximated by the length of stay in the literature. Thus, the longer migrants stay, the more they become integrated into receiving societies, the more difficult it becomes to return, and the more they are inclined to settle (e.g., van Baalen and Müller 2009), even to naturalize. Thus, return migration is conceptualized as a cause and/or a consequence of “integration failure”, or as de Haas and Fokkema (2011) stated, “While ‘winners’ settle, ‘losers’ return”.

Nevertheless, this explanation falls short for three reasons. First, remigration or return migration can also be the result of a “success” of the migration project, as was proposed by the New Economics of Migration. In fact, initial migration being conceptualized as a strategy to improve the economic situation of the household in the origin country (Stark 1991), emigration, and particularly return migration, is an indicator of economic success (de Haas and Fokkema 2011). Even more so, in today’s dynamic global market for human capital, the increased mobility of the highly skilled might be explained by a specific career step and thus an anticipated short duration of stay. As shown by Massey and Akresh (2006), “The bearers of skills, education, and abilities seek to maximize earnings in the short term while retaining little commitment to any particular society or national labour market over the longer term”. Thus, the two theoretical approaches are not mutually exclusive or contradictory (Constant and Massey 2002), even less so in the context of high-income countries, such as Switzerland. Hence, the actual remigration results in either a “success”, that is, the achievements of one’s aspirations in the host country, or a “failure” to achieve these aspirations (Borjas and Bratsberg 1996).

Second, the absence of socio-cultural integration as defined above might not always be a factor that explains remigration intentions. In fact, there might be cases of non-integrated ethnic minorities who intend to remain in the country of destination. Moreover, the integration is not necessarily dependent upon the length of stay but rather on the pace of integration. Finally, structural integration and socio-cultural integration do not always go hand-in-hand, thus making it difficult to decide whether the overall migration is a “success” or a “failure”.

Third, although remigration and naturalization intentions appear to be opposite outcomes of the migration trajectory, they might be held in conjunction. Acquiring Swiss citizenship when holding citizenship from a country outside of the EU/EFTA for example provides access to the European labour market and thus furthers mobility. In addition, holding both passports (that of the origin country citizenship and the Swiss one) guarantees the possibility of re-entering Switzerland and thus allows a more transnational lifestyle between both countries, even more so after retirement. Finally, and because we are not measuring behaviour but “only” intentions, undecided individuals who are neither satisfied nor dissatisfied with their life might declare fostering remigration and naturalization intentions as possible future options.

2.2 Determinants

What follows is a separate discussion of determinants of remigration and naturalization intentions.

Remigration Intentions

Although most studies find that the absence of structural integration is more important in explaining remigration intentions than are socio-cultural factors, some studies find the opposite (de Haas et al. 2015; Carling and Pettersen 2014). Thus, developing a “one-fits it all” explanation or theory for remigration intentions (Snel et al. 2015) is unlikely because remigration intentions diverge according to the migrant’s profile, the contexts in which migration occurs and thus opportunities in both origin and destination country, and initial migration intentions (Güngör and Tansel 2008; Soon 2008; de Haas and Fokkema 2011).

Also, although most studies consider migrants altogether, some scholars focus on one specific type of migrant, referring either to the profile (e.g., highly skilled migrants) or to the stage in their life course (e.g., students and workers). Those studies demonstrate that the determinants influencing remigration intentions differ considerably according to the type of migrant or reason of migration; a business migrant or a student for example does not have the same migratory projects as a family migrant (Mak 1997). Thus, age, which is correlated with reason for immigration (student, work, and family), also presents an important role because it is negatively correlated with the intention to migrate (Coulter et al. 2011; Ette et al. 2016). Nevertheless, Waldorf (1995), analysing return intentions of guest-workers in Germany, noted an increase in the probability of intending to return in the period prior to retirement.

Gender differentials in migratory behaviour are well documented. In particular, concerning labour migration, women are more willing to follow their partner when emigrating than the other way around (Vandenbrande et al. 2006); the literature findings on international migratory intentions are often not conclusive (van Dalen and Henkens 2013). The family situation has been shown to be an important factor, in which singles and childless individuals are more likely to have emigration intentions due to their independence and higher flexibility. However, Waldorf (1995) emphasizes the importance of the spouse’s place of residence.

In general, transnational ties affect migrants’ intentions to leave the host country. Family encouragement and support in the home country is positively related to intentions to repatriate (Güngör and Tansel 2008; Tharenou and Caulfield 2010). Van Dalen and Henkens (2013) confirmed these results by analysing the role of the presence of a partner in the country of origin as a factor intervening in return intentions. Several studies even found that family and relationship ties in the country of origin play a more important role in return decisions than economic factors do (Harvey 2011).

The social, economic and legal conditions in the migrant’s origin country, approximated by the migrant’s citizenship, also have an effect (Massey and Akresh 2006). According to Carling and Pettersen (2014), the national origin contributes strongly to explaining differences in return intentions, even after controlling for other background variables. One explanation might be the differing “access” to onward mobility. In fact, whereas return migration is generally an option for voluntary migrants, onward migration might be limited due to the absence of bilateral or multilateral international agreements on the movement and settlement of persons. Thus, for onward migration, the migration policy of the anticipated destination country – which can provide specific conditions for sub-groups defined according to their education or profession for example – might strongly constrain the individual’s capability to move and therefore structure further movements. Thus and concerning the labour market, remigration (return and onward migration) for successful and highly qualified migrants might be easier, not least because of their better access and exposure to information. Finally, Ette et al. (2016) found a significantly positive relationship between migrants’ rights provided by the current country of residence and permanent settlement intentions. Newcomers who are provided permanent settlement rights or a transparent process towards a secure legal status invest more in the integration process, subsequently extending the intended duration of stay.

Another set of factors that plays an important role is the feasibility of and the preparedness to move (Tharenou and Caulfield 2010). This point primarily refers to the prior migration setting before leaving the country of origin. Previous trips abroad increase the likelihood to leave the destination country (Massey and Akresh 2006; de Haas and Fokkema 2011). Cassarino (2004) argued that the returnee’s preparedness refers to a voluntary act that must be supported by the gathering of sufficient tangible (e.g., financial capital) and intangible resources (contacts, relationships, skills, and acquaintances). Such resources can have been brought by the migrant prior to leaving his/her country of origin (e.g., social capital), can be mobilized during the initial migration experience, or can refer to information about post-return conditions in the country of origin. Moreover, social capital has an influence on migratory intentions (Cassarino 2004), in which highly skilled occupations often require spatial flexibility (van Ham et al. 2001). Several studies also showed a positive correlation between educational level and migration intentions, arguing that higher levels of education increase employment opportunities and access to information (Coulter et al. 2011; Sapeha 2017; Ette et al. 2016), thereby decreasing the relative cost of migration.

An important set of factors constitutes the migrant’s embeddedness in and satisfaction with the host country. Therefore, expatriates who are less embedded in the destination country in their career and community have fewer barriers to return and lower costs arising from doing so (Tharenou and Caulfield 2010). Although duration of residence does not automatically determine a higher propensity to settle (di Belgiojoso and Ortensi 2013), a crucial role is played by other factors. Factors that actually have a negative effect on the migrant’s intentions to remigrate include living with a partner of the host country (Pungas et al. 2012), having school-aged children (e.g. Khoo and Mak 2000; Massey and Akresh 2006), owning a family business in the current country of residence (de Haas and Fokkema 2011), being integrated into a social network (van Dalen and Henkens 2007, 2013) and speaking the local language of the host country (Steiner and Velling 1992; Dustmann 1999; Ette et al. 2016).

Similarly, migration intentions are also closely linked to satisfaction with life in the country of residence (Mara and Landesmann 2013; Ivlevs 2015; Hercog and Siddiqui 2014), although one must consider that those factors particularly depend upon the comparative advantage of the possible destination country and the residence country. Thus, according to Pungas et al. (2012), over-education in the labour market, and therefore job dissatisfaction, is associated with an elevated willingness to return. However, not only job and career situation and prospects (Sapeha 2017) but also housing situation (Waldorf 1995), personal life and family satisfaction (Khoo and Mak 2000; Jensen and Pedersen 2007), the subjective well-being associated with the stay (Steiner and Velling 1992), or an experience of racism and discrimination (Steinmann 2018; de Haas et al. 2015) are important factors for remigration intentions.

Naturalization Intentions

As mentioned, the literature on naturalization intentions is much smaller than the one on remigration intentions. Existing studies suggest however that the intention to naturalize is primarily triggered by legal considerations, social and cultural integration and emotional identification with the host country society and less by structural integration (Hochman 2011; Leibold 2006).

In fact, the decision to naturalize is not only a rational individual choice but also subject to formal conditions. Reaching a naturalization decision is a complex process, involving not only the foreigner but also the origin and destination country’s legal provisions (e.g., duration of residence) and their administrative practices (Özcan and Institut 2002; Wanner and Steiner 2012).

Mehrländer showed in the German context, for example, that EU citizens (Italians and Greek) present lower naturalization intentions than do Turkish citizens (Mehrländer et al. 1996, cited by Leibold 2006). The main reasons for the interest of Turkish nationals are legal advantages (right of residence, right to vote and freedom of travel in the EU), personal roots in Germany and a lowered level of attachment to the country of origin. Among the arguments against naturalization frequently mentioned, one can find the obligation to abandon one’s own nationality, legal disadvantages in Turkey, the loss of right to return and an already secure right of residence in Germany (Sauer and Goldberg 2001; Mehrländer et al. 1996, both cited by Leibold 2006).

Diehl (2002) showed that a plan to acquire the German passport among Turkish citizens is largely explained by emotional identification with Germany, German as a lingua franca among friends, being born in Germany and low religiosity. Language skills, increased duration of residence, social networks or marrying members of the receiving society increase the immigrants’ naturalization intentions (Diehl and Blohm 2008, cited by Hochman 2011; Leibold 2006; Zimmermann et al. 2009). In addition, discrimination and negative attitudes towards individuals with a migration background hindered intentions to naturalize (Portes and Curtis 1987; Hochman 2011).

Concerning structural integration, results are contradictory. Although home ownership is often found to increase naturalization intentions (Diehl and Blohm 2003; Portes and Curtis 1987), Massey and Akresh (2006) showed in the United States (US) that those with high earnings and property ownership are actually less likely to intend to naturalize. Although several authors (Portes and Curtis 1987; Yang 1994) find that higher education increases naturalization intentions, Massey and Akresh (2006) do not find significant differences between educational groups. One reason why structural integration might be more weakly associated with naturalization integration could be the fact that “similar conditions govern[…] the rights and obligations of legal permanent foreign residents and naturalized individuals” (Hochman 2011). Thus, due to the relative comfort achieved in connection with permanent residency status, naturalization is not expected to yield a higher utility for labour market integration (Hochman 2011).

Finally, results concerning family characteristics are somewhat inconclusive. Although the respondents’ marital status in Hochman’s analyses (2011) had no significant effect, Massey and Akresh (2006) showed that married individuals have a lower propensity to intend to naturalize.

2.3 Research Question and Hypotheses

This chapter aims at understanding the factors that trigger remigration and/or naturalization intentions in a high-income country setting. Based on the literature, four hypotheses guide our research.

-

[H1]

Remigration intentions are largely explained by weak structural integration.

-

[H2]

Based on the assimilation and integration theories, migrant’s embeddedness in and satisfaction with the host country are the most decisive factors explaining naturalization intentions.

-

[H3]

Based on the first two hypotheses, and very generally, remigration and naturalization intentions are explained by the same factors but with opposing effects. Moreover, the migrant’s citizenship, and thus the social, legal and economic conditions in the country of origin, explain differences in emigration and naturalization intentions. We expect that EU/EFTA migrants foster higher remigration intentions, whereas third-country nationals from non-industrialized countries intend rather to naturalize.

-

[H4]

Finally, remigration and naturalization intentions are primarily held in conjunction by third-country nationals who would like to “secure” their access to the European labour market and thus to further mobility.

3 Methods and Data

The analyses are based on the Migration-Mobility Survey 2016 (see Chap. 2). In contrast with other surveys conducted in Switzerland, it focusses on relatively recently arrived immigrants, with a duration of residence of up to 10 years, and thus captures the attitudes towards the migration experience based on a short(er) duration of residence in the destination country. Moreover, and most importantly for our study, it includes information on both remigration and naturalization intentions, two dimensions that are rarely covered in general population surveys or even in specific immigrant surveys.

Consequently, our dependent variable is the immigrants’ intentions, based on the following questions (see Table 12.1). “How many more years would you like to stay in Switzerland?” If the response fell between 1–20 years, “How often have you considered emigrating from Switzerland in the last three months?” Concerning naturalization intentions, we consider the following question: “Do you intend to apply for the Swiss nationality in the future?” In addition, because the question on naturalization intentions was asked to the whole sample, we obtain a fourth category of people fostering both types of intentions. Table 12.1 summarizes the construction of our indicator and the four response categories.

The analyses are conducted including the entire sample, 5973 individuals, corresponding to 458,969 weighted observations. In addition to descriptive analyses of the sample and immigrants’ intentions by origin, using a multiple correspondence analysis, we run a multinomial logistic regression (see Chap. 7 for model specifications). Based on the availability of a discrete dependant variable that represents four outcomes that do not have a natural ordering, we estimate the effect of different explanatory factors on immigrants’ remigration intentions, naturalization intentions or remigration and naturalization intentions. The base outcome is settlement intentions (that is, not having any intentions), and the estimated coefficients were transformed to relative risk ratios.Footnote 6

Based on the literature and data availability, the following explanatory variables were categorized into four groups of factors. First, basic demographics include age (continuous, 24–64 years), gender, origin (11 groups of the survey: Germany, Austria, France, Italy, United Kingdom (UK), Spain, Portugal, US/Canada, India, South America and West Africa), having (or not having) children and the reasons for immigration. For the latter, a cluster analysisFootnote 7 categorized the individuals into five groups based on the reasons for immigration they had declared. We thus distinguish between individuals who primarily came for professional reasons, for educational reasons, to accompany the family, to start a family, or for lifestyle reasons/to gain new experiences/for the social network. Second, transnational ties considers partner’s place of residence (Switzerland, abroad or not having a partner) and friends’ place of residence (Switzerland, abroad, both in Switzerland and abroad). Third, feasibility and preparedness are composed of number of prior international moves (continuous, from 0 to 20 times), holding (or not holding) tertiary education, and income (puts money aside vs. spends all income or more). Fourth, embeddedness in and satisfaction with the host country is composed of satisfaction with the decision to move to Switzerland (or not satisfied), duration of residence (continuous, from 0 to 10 years), experiences (or not experiences) of racism/discrimination in Switzerland and improved (or not improved) labour market situation compared with before migrating to Switzerland.

4 Results

4.1 Immigrants’ Intentions

Most of the recently arrived migrants in Switzerland do not express any intentions to remigrate (see Table 12.2). In fact, 34% would even like to naturalize, whereas 35% have no intentions to leave Switzerland or to naturalize. One of four migrants (26%) intends to remigrate and 6% declare fostering both remigration and naturalization intentions.

When asked for the reasons for not wishing to acquire Swiss citizenship, almost one-half of the participants declared that they do not want to give up their current citizenship, 36% do not see any benefit in doing so, and 20% do not want to go through the process, which is too expensive, complicated and long (see Table 12.3). When asked for the reasons they intend to apply for Swiss citizenship in the future, more than one-half of the participants (56%) declared that they feel that they belong in Switzerland, 43% said that their spouse or partner and/or close family members are Swiss, and 32% believe that doing so will give them better professional opportunities.

Surprisingly, men more frequently foster naturalization intentions than women, whereas the opposite applies concerning remigration intentions. No important variations can be observed concerning mean age at immigration over the four categories, although migrants who intend to settle were slightly older at immigration with respect to the mean observed for the total sample; individuals who would like to naturalize and remigrate were the youngest at immigration. Moreover, the educational level appears to affect settlement and remigration intentions, in which tertiary-educated individuals more frequently intent to remigrate and less frequently intent to settle.

The reason for immigrating to Switzerland influences immigrants’ intentions. The highest share of immigrants came for professional reasons to Switzerland. Their distribution across the three categories – settlement, naturalization and remigration – is the most similar (30%–35%), indicating a relatively homogeneous group of migrant workers. Nevertheless, they present the highest share of remigration intentions and the lowest share of naturalization intentions. Rather similar to this first group are migrants who declare having immigrated for educational reasons or to accompany the family. Additionally and unsurprisingly, almost one-half of all individuals who came to Switzerland to start a family foster naturalization intentions, whereas only 20% declare remigration intentions. Finally, lifestyle migrants present the lowest shares of remigration intentions (16%) and thus the highest share of individuals who would like to settle (with or without naturalization intentions).

Family status does not play an important role. Migrants with children (57% of the total sample) slightly more frequently present naturalization and settlement intentions and slightly less frequently remigration intentions than do those with no children. Although these distributions indicate that children render an international movement somewhat more challenging, the presence of a child in this particular population, in which 60% hold a tertiary degree, definitely does not present a barrier to remigration.

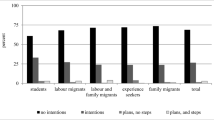

One further result considers the differing strategies based on the origin. In general, whereas EU/EFTA migrants show remigration intentions more frequently than non-EU/EFTA citizens, the latter more frequently have naturalization intentions and remigration and naturalization intentions, thus supporting – at first sight – some of our research hypotheses (see Table 12.2). Figure 12.1 plots the results of multiple correspondence analyses, entering the origin group variable and an extension of the four types of intentions, thus distinguishing for remigration intentions the destination, that is, onward or return migration. Among the individuals who expressed an intention to remigrate, 65% wish to return to their country of origin.

The different intentions are nicely delimited in the four partitions of Fig. 12.1, and we detect origin-specific strategies. Germans, Portuguese and Austrians foster primarily settlement intentions. The last two are situated the furthest away from naturalization intentions. This point might be explained by the fact that the Portuguese declare having a very strong feeling of attachment to their home country – a feeling that might also explain their relative closeness to return migration in the graph – and Austria does not allow for dual citizenship.

Naturalization intentions are very strong among individuals from France, Italy and from the two non-industrialized non-EU/EFTA regions, that is, West Africa and South America. Compared with the other EU/EFTA origin groups, French citizens are in fact the only group that feels more strongly attachedFootnote 8 to Switzerland than to their country of origin. Individuals from South America often declare fostering naturalization and onward migration intentions, confirming that holding both in conjunction might be a strategy to access the European labour market for migrants from outside the EU/EFTA area.

Concerning remigration intentions, whereas the Spanish are associated with return migration, British citizens are situated halfway between return and onward migration intentions. Indians are somewhere in between naturalization, settlement and return. Finally, US citizens and Canadians are, on the one hand, associated with onward migration intentions, intentions that are most likely due to their high level of qualification and thus to their professional mobility. On the other hand, this group is also clearly associated with naturalization and return intentions. This result might be explained by a certain discontent by US citizens with their home country and/or the taxes they must pay in their origin country, even when living abroad.

4.2 Determinants

Table 12.4 presents the results of the relative risk ratios of the multinomial regression. Remigration intentions are largely expressed by migrants who came for work- or study-related reasons. Thus, considering the effect of unemployment and being a househusband/wife on remigration intentions, we find support for our first hypothesis. Remigration intentions are explained by weak integration on the labour market. Nevertheless, social integration also appears to be decisive because the absence of friends and the partner triggers remigration intentions. The fact that no or weak satisfaction with the migration to Switzerland compared with being satisfied is associated with the highest relative risk ratios for remigration intentions further supports these results. In any case, when not being well integrated, the qualification level might then act as a facilitator for remigration; a tertiary degree provides easier access to other countries’ labour markets and thus to mobility.

US/Canadian and UK citizens, who are often involved in expat migratory strategies, show the highest risk ratios to intend to emigrate. The results concerning the link between lowered remigration intentions and origin are less clear; West Africans, Indians and Portuguese present the lowest risk ratios to intend to leave Switzerland. The former is the one group of the sample that originates from less developed countries in which they do not want or cannot return. It is also the group that declares most often having been subject to discrimination (52% of all West Africans declare having experienced situations of prejudice or discrimination in Switzerland in the last 24 months), explaining the lowered remigration intentions when having experienced discrimination.

Naturalization intentions are largely expressed by migrants who came to Switzerland to start a family or for lifestyle reasons and are thus involved in more-permanent migratory strategies. Thus, confirming our second hypothesis, these intentions are found largely explained by social integration (presence of friends and the partner in Switzerland), increasing duration of residence, general satisfaction with the migration experience and absence of discrimination. The last might be explained by either dissatisfaction with the current residence country’s society and/or the presentiment that the outcome of the naturalization procedure might also be influenced by the same anti-immigrant feelings.

Because the migratory strategy is more permanent, even unemployment does not hinder naturalization intentions. Finally and due to the restrictive migratory policy in place for non-EU/EFTA countries that control migrants’ entry, admission and stay, citizens from non-industrialized, non-EU/EFTA countries, that is South America and West Africa, had to overcome the highest barriers to migrate to Switzerland and thus present the highest relative risk ratios to foster naturalization intentions compared with settlement intentions.

Thus, related to our third hypothesis, several factors explain remigration intentions and naturalization intentions but in opposing directions. Naturalization intentions are lowered, and remigration intentions significantly increased for most origin groups compared with the West Africans (Austria, France, UK, Spain and US/Canada) when the partner lives abroad compared with him/her residing in Switzerland, when friends live abroad compared with them residing in Switzerland, and when dissatisfied with the migration to Switzerland. Finally, naturalization intentions are increased, and remigration intentions lowered for lifestyle migrants compared with individuals who arrived for professional reasons.

Interestingly, we find three cases in which the direction of the relative risk ratios is the same, thus contradicting our third hypothesis. First, experiencing discrimination lowers not only naturalization intentions but also remigration intentions. Second, and consistent with most studies on the relationship between educational level and both types of intentions, holding a tertiary degree of education (compared with Secondary I and II degrees) increases the intention to naturalize and remigrate, a result that emphasizes how high educational attainment fosters the migrant’s agency. Third, being unemployed at the moment of the survey (compared with employed) increases both types of intentions.

We now turn to the last outcome, that is, the conjunction of naturalization and remigration intentions. First and in contrast to the first two outcomes, the partner’s and friends’ places of residence do not have a significant effect, whereas the number of prior international moves slightly does. These results might point to a strategy of international mobility in which Swiss citizenship acts as a facilitator. The fact that third-country nationals, except for Indians, present the highest relative risk ratios would then confirm this impression and our fourth hypothesis. Nevertheless, because most of the participants must wait several years to apply for Swiss citizenship, it is not certain that we can interpret these intentions as being strategic. More realistically, they are most likely an expression of the immigrant not being certain about the future, in which both remigration and naturalization continue to present actual options.

Finally, we note two final results. Surprisingly, whether they have children does not influence immigrants’ intentions. Although when migrants have children, the relative risk ratios point towards an increase in naturalization intentions, conjunction of naturalization and remigration intensions, and a decrease in remigration intentions, none of the ratios are statistically significant. Additionally, income does not yield a significant effect on any of the three outcomes.

5 Conclusion

In this article, we aimed at obtaining insights into the factors explaining immigrants’ intentions. Very generally, we found that most of the recently arrived migrants in Switzerland do not express any intentions to remigrate (69%); of these, 34% would even like to naturalize, most likely reflecting a rather positive impression of their migration experience. This result corresponds to other findings, in which 60% of immigrants intend to stay permanently (Geurts and Lubbers 2017, for immigrants in the Netherlands; Tezcan 2018, for Mexicans in the US).

In their article, Massey and Akresh (2006) view “emigration as a dynamic decision rooted in the migrant’s objective circumstances and psychological orientation to the host country”. In fact, studying an immigrant’s intentions somehow summarizes the migrant’s experiences in the destination country and thus might affect his/her investment in the integration process. We were in fact able to unfold two different strategies. First, immigrants who are involved in a more permanent migratory strategy, and thus have expressed naturalization intentions, are often family or lifestyle migrants who are socially well integrated, have a higher duration of residence and are satisfied with their migration experience. Unemployment even fosters naturalization intentions, most likely because of the more long-term intentions of the stay.

Second, remigration intentions are largely expressed by immigrants who came for work or study reasons to Switzerland. Thus, weak labour market integration (unemployed or staying at home) causes remigration intentions. Primarily citizens from the US/Canada or the UK express remigration intentions; these groups are likely most often involved in highly mobile expat migratory trajectories. Nevertheless, social integration and satisfaction with the stay are also important determinants.

However, the relationship between the level of integration and immigrants’ intentions is more complex. In fact, 6% of the sample declared fostering naturalization and remigration intentions in conjunction. Although one could argue that this outcome presents a strategy of international mobility in which Swiss citizenship acts as a facilitator, it is not certain that we can interpret these intentions as being strategic. More realistically, they might be an expression of the immigrant not being certain about the future, in which both remigration and naturalization continue to present an option.

Finally, we would like to emphasize the role of education. In fact, holding a tertiary degree increases all types of intentions by not only increasing the likelihood of obtaining Swiss citizenship but also facilitating access to mobility. This result emphasizes how high educational attainment fosters the migrant’s agency to choose whatever migratory trajectory they desire to follow despite the more restrictive migration regime that Switzerland has introduced for non-EU/EFTA nationals.

Unfortunately, several determinants identified in the literature could not be considered in this research primarily due to data unavailability. We were, for instance, unable to integrate factors such as psychological resources (van Dalen and Henkens 2013; Canache et al. 2013; Cai et al. 2014) or societal dimensions (e.g., the political climate towards foreigners (Reitz 1998; Bommes 2012; Ette et al. 2016)).

Also, we also would like to emphasize the dynamic nature of immigrants’ intentions. In fact, whatever mechanism triggers or hinders them, they can be altered during the migratory path. For example, sudden life course changes can trigger or hinder remigration intentions, such as starting a new job or having a baby (Kley 2011). In addition, Leibold (2006), citing different studies, mentions financial motives and the education of children as reasons for postponing the emigration decision. Thus, even though they might constitute a good predictor for future behaviour, they should not be taken as a definitive decision that will certainly be translated into reality.

Notes

- 1.

See Migration-Mobility Indicators of the nccr – on the move, Remigration, http://nccr-onthemove.ch/knowledge-transfer/migration-mobility-indicators/how-many-migrants-settle-in-switzerland/. Accessed 6 March 2018.

- 2.

See Migration-Mobility Indicators of the nccr – on the move, Naturalization, http://nccr-onthemove.ch/knowledge-transfer/migration-mobility-indicators/how-many-migrants-get-naturalized-over-time/. Accessed 6 March 2018.

- 3.

Ordinary naturalization criteria were modified as of January 1, 2018, lowering for example the duration of residence to 10 years.

- 4.

Information from https://www.sem.admin.ch/sem/en/home/themen/buergerrecht/einbuergerung/erleichterte_einbuergerung.html. Accessed 2 February 2018.

- 5.

The causal relationship is however not clear. Are the well-integrated predominantly settling down, or do the settled-down integrate better?

- 6.

RRR are the ratio of relative risks for the outcome versus base category (settlement intentions) for each given covariate compared with a reference category. A relative risk of 2 means twice the risk, a risk of 0.5 implies half the risk.

- 7.

We applied the K-means method, a partitioning method that iterates between computing K cluster centroids by minimizing the within cluster variance and updating cluster memberships (Hastie et al. 2009).

- 8.

Attachment is measured through the two questions of the Migration-Mobility Survey: “On a scale from 0 (no feeling of attachment) to 7 (strong feeling of attachment), to what extent do you have a feeling of attachment to Switzerland/to your country of origin?”

References

Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471–499. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601164939.

Bommes, M. (2012). Welfare systems and migrant minorities: The cultural dimension of social policies and its discriminatory potential. In C. Boswell & G. D’Amato (Eds.), Immigration and social systems: Collected essays of Michael Bommes (pp. 83–106). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Borjas, G. J., & Bratsberg, B. (1996). Who leaves? The outmigration of the foreign-born. Review of Economics and Statistics, 78(1), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.3386/w4913.

Cai, R., Esipova, N., Oppenheimer, M., & Feng, S. (2014). International migration desires related to subjective well-being. IZA Journal of Migration, 3(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-9039-3-8.

Canache, D., Hayes, M., Mondak, J. J., & Wals, S. C. (2013). Openness, extraversion and the intention to emigrate. Journal of Research in Personality, 47(4), 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.02.008.

Carling, J., & Pettersen, S. V. (2014). Return migration intentions in the integration–transnationalism matrix. International Migration, 52(6), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12161.

Cassarino, J.-P. (2004). Theorising return migration: The conceptual approach to return migrants revisited. International Journal on Multicultural Studies, 6(2), 253–279.

Constant, A., & Massey, D. S. (2002). Return migration by German guestworkers: Neoclassical versus new economic theories. International Migration, 40(4), 5–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00204.

Coulter, R., van Ham, M., & Feijten, P. (2011). A longitudinal analysis of moving desires, expectations and actual moving behavior. Environment and Planning A, 43(11), 2742–2760. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44105.

de Haas, H., & Fokkema, T. (2011). The effects of integration and transnational ties on return migration intentions. Demographic Research, 25, 755–782.

de Haas, H., Fokkema, T., & Fihri, M. F. (2015). Return migration as failure or success? The determinants of return migration intentions among Moroccan migrants in Europe. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 16(2), 415–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-014-0344-6.

De Jong, G. F. (2000). Expectations, gender, and norms in migration decision-making. Population Studies, 54(3), 307–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/713779089.

di Belgiojoso, E. B., & Ortensi, L. E. (2013). Should I stay or should I go? The case of Italy. Rivista Italiana di Economia, Demografia e Statistica, 67(3/4), 31–38.

Diehl, C. (2002). Wer wird Deutsche/r und warum?: Bestimmungsfaktoren der Einbürgerung türkisch-und italienischstämmiger junger Erwachsener. Zeitschrift für Bevölkerungswissenschaft, 27(3), 285–312.

Diehl, C., & Blohm, M. (2003). Rights or identity? Naturalization processes among “labor migrants” in Germany. International Migration Review, 37(1), 133–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2003.tb00132.x.

Diehl, C., & Blohm, M. (2008). Die Entscheidung zur Einbürgerung: Optionen, Anreize und identifikative Aspekte. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 60(4), 437–464.

Dustmann, C. (1999). Temporary migration, human capital, and language fluency of migrants. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 101(2), 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9442.00158.

Engler, M., Erlinghagen, M., Ette, A., Sauer, L., Scheller, F., Schneider, J., et al. (2015). International Mobil. Motive, Rahmenbedingungen und Folgen der Aus- und Rückwanderung deutscher Staatsbürger. (Vol. 2015-01). Berlin und Wiesbaden: Forschungsbereich beim Sachverständigenrat deutscher Stiftungen für Integration und Migration (SVR), Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung (BiB), Lehrstuhl für Empirische Sozialforschung an der Universität Duisburg-Essen.

Ette, A., Heß, B., & Sauer, L. (2016). Tackling Germany’s demographic skills shortage: Permanent settlement intentions of the recent wave of labour migrants from non-European countries. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 17(2), 429–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0424-2.

Favell, A. (2008). Eurostars and eurocities. Free movement and mobility in an integrating Europe (Studies in Urban and Social Change). Malden: Blackwell.

Favell, A., & Recchi, E. (2009). Pioneers of European integration: An introduction. In E. Recchi & A. Favell (Eds.), Pioneers of European integration: Citizenship and mobility in the EU (pp. 1–25). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Geurts, N., & Lubbers, M. (2017). Dynamics in intention to stay and changes in language proficiency of recent migrants in the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(7), 1045–1060. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1245608.

Güngör, N. D., & Tansel, A. (2008). Brain drain from Turkey: An investigation of students’ return intentions. Applied Economics, 40(23), 3069–3087. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840600993999.

Harvey, W. S. (2009). British and Indian scientists in Boston considering returning to their home countries. Population, Space and Place, 15(6), 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.526.

Harvey, W. S. (2011). Immigration and emigration decisions among highly skilled British expatriates in Vancouver. In K. Nicolopoulou, M. Karatas-Özkan, A. Tatli, & J. Taylor (Eds.), Global knowledge work: Diversity and relational perspectives (pp. 33–56). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., & Friedman, J. (2009). The elements of statistical learning: Data mining, inference, and prediction (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Hercog, M., & Siddiqui, M. Z. (2014). Experiences in the host countries and return plans: The case study of highly skilled Indians in Europe. In G. Tejada, U. Bhattacharya, B. Khadria, & C. Kuptsch (Eds.), Indian skilled migration and development. To Europe and back (pp. 213–235). New Delhi: Springer.

Hochman, O. (2011). Determinants of positive naturalisation intentions among Germany’s labour migrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37(9), 1403–1421. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2011.623615.

Ivlevs, A. (2015). Happy moves? Assessing the link between life satisfaction and emigration intentions. Kyklos, 68(3), 335–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12086.

Jensen, P., & Pedersen, P. J. (2007). To stay or not to stay? Out-migration of immigrants from Denmark. International Migration, 45(5), 87–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2007.00428.x.

Khoo, S. -E., & Mak, A. (2000). Permanent settlement or return migration: The role of career and family factors. Paper presented at the 10th Biennial Conference of the Australian Population Association, Melbourne, 28 November to 1 December.

Kley, S. (2011). Explaining the stages of migration within a life-course framework. European Sociology Review, 27(4), 469–486. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcq020.

Leibold, J. (2006). Immigranten zwischen Einbürgerung und Abwanderung. Eine empirische Studie zur bindenden Wirkung von Sozialintegration. Göttingen: Georg-August-Universität.

Loretan, A., & Wanner, P. (2017). The determinants of naturalization in Switzerland between 2010 and 2012. NCCR On the move Working Paper, 13.

Lu, M. (2011). Analyzing migration decisionmaking: Relationships between residential satisfaction, mobility intentions, and moving behavior. Environment and Planning A, 30(8), 1473–1495. https://doi.org/10.1068/a301473.

Mak, A. S. (1997). Skilled Hong Kong immigrants’ intention to repatriate. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 6(2), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/011719689700600202.

Mara, I., & Landesmann, M. (2013). Do I stay because I am happy or am I happy because I stay? Life satisfaction in migration, and the decision to stay permanently, return and out-migrate. Norface Migration Discussion Paper, 2013-08.

Massey, D. S., & Akresh, I. R. (2006). Immigrant intentions and mobility in a global economy: The attitudes and behavior of recently arrived US immigrants. Social Science Quarterly, 87(5), 954–971. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2006.00410.x.

Mehrländer, U., Ascheberg, C., & Ueltzhöffer, J. (1996). Repräsentativuntersuchung ‘95: Situation der ausländischen Arbeitnehmer und ihrer Familienangehörigen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Berlin: Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Sozialordnung.

Özcan, V., & Institut, S. (2002). Einbürgerungsverhalten von Ausländern: beeinflussende Faktoren auf der Angebots- und Nachfrageseite. Neuchâtel: Swiss Forum for Migration and Population Studies.

Portes, A., & Curtis, J. W. (1987). Changing flags: Naturalization and its determinants among Mexican immigrants. International Migration Review, 21(2), 352–371. https://doi.org/10.2307/2546320.

Pungas, E., Toomet, O., Tammaru, T., & Anniste, K. (2012). Are better educated migrants returning? Evidence from multi-dimensional education data. Norface Migration Discussion Paper, 2012-18.

Reitz, J. G. (1998). Warmth of the welcome: The social causes of economic success for immigrants in different nations and cities. Boulder: Westview Press.

Sapeha, H. (2017). Migrants’ intention to move or stay in their initial destination. International Migration, 55(3), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12304.

Sauer, M., & Goldberg, A. (2001). Die Lebenssituation und Partizipation türkischer Migranten in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Ergebnisse der zweiten Mehrthemenbefragung. Münster/Hamburg/London: Lit.

Snel, E., Faber, M., & Engbersen, G. (2015). To stay or return? Explaining return intentions of Central and Eastern European labour migrants. Central and Eastern European Migration Review, 4(2), 5–24.

Soon, J.-J. (2008). The determinants of international students’ return intention. University of Otago. Economics Discussion Papers, 0806.

Stark, O. (1991). The migration of labour. Cambridge: Basel Blackwell.

Steiner, I. (2018) Settlement or mobility? Immigrants’ re-migration decision-making process in a high-income country setting. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 20(1), 223–245.

Steiner, V., & Velling, J. (1992). Re-migration behaviour and expected duration of stay of guest-workers in Germany. ZEW Discussion Papers, 92–14.

Steinmann, J.-P. (2018). One-way or return? Explaining group-specific return intentions of recently arrived Polish and Turkish immigrants in Germany. Migration Studies. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnx073.

Tezcan, T. (2018). ‘I (do not) know what to do’: How ties, identities and home states influence Mexican-born immigrants’ return migration intentions. Migration and Development, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2018.1457427.

Tharenou, P., & Caulfield, N. (2010). Will I stay or will I go? Explaining repatriation by self-initiated expatriates. Academy of Management Journal, 53(5), 1009–1028. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2010.54533183.

van Baalen, B., & Müller, T. (2009). Return intentions of temporary migrants: The case of Germany. Paper presented at the Second Conference of Transnationality of Migrants, Louvain, 23–24 January. http://www.cepr.org/meets/wkcn/2/2395/papers/MuellerFinal.pdf. Accessed 5 Jan 2015.

van Dalen, H. P., & Henkens, K. (2007). Longing for the good life: Understanding emigration from a high-income country. Population and Development Review, 33(1), 37–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2007.00158.x.

van Dalen, H. P., & Henkens, K. (2008). Emigration intentions: mere words or true plans? Explaining international migration intentions and behavior. Discussion Paper CentER, 2008-60.

van Dalen, H. P., & Henkens, K. (2013). Explaining emigration intentions and behaviour in the Netherlands, 2005–10. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 67(2), 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2012.725135.

van Ham, M., Mulder, C. H., & Hooimeijer, P. (2001). Spatial flexibility in job mobility: Macrolevel opportunities and microlevel restrictions. Environment and Planning A, 33(5), 921–940. https://doi.org/10.1068/a33164.

Vandenbrande, T., Coppin, L., van der Halle, P., Ester, P., Fourage, D., Fasang, A., et al. (2006). Mobility in Europe. Analysis of the 2005 Eurobarometer survey on geographical and labour market mobility. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Waldorf, B. (1995). Determinants of international return migration intentions. The Professional Geographer, 47(2), 125–136.

Wanner, P., & Steiner, I. (2012). La naturalisation en Suisse. Evolution 1992–2010 (Documentation sur la politique migratoire). Berne: Commission fédéral pour les questions de migration (CFM).

Yang, P. Q. (1994). Explaining immigrant naturalization. International Migration Review, 28(3), 449–477. https://doi.org/10.2307/2546816.

Zimmermann, K. F., Constant, A. F., & Gataullina, L. (2009). Naturalization proclivities, ethnicity and integration. International Journal of Manpower, 30(1/2), 70–82. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720910948401.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Steiner, I. (2019). Immigrants’ Intentions – Leaning Towards Remigration or Naturalization?. In: Steiner, I., Wanner, P. (eds) Migrants and Expats: The Swiss Migration and Mobility Nexus. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05671-1_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05671-1_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-05670-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-05671-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)