Abstract

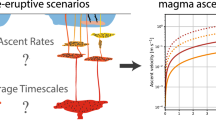

One of the key issues in utilizing precursor signals of volcanic eruption is to reliably interpret geophysical and geochemical data in terms of magma movement towards the surface. An important first step is to identify where the magma is stored prior to ascent. This can be studied through phase-equilibrium experiments designed to replicate the phase assemblage and compositions of natural pyroclasts or by measuring volatiles in melt inclusions from previous eruptions. The second crucial step is to characterize the magmatic conditions and processes that will guide the eruption style. This may be addressed through controlled dynamic decompression or deformation experiments to examine the different rates that govern the kinetics of syn-eruptive degassing, crystallization, and strain. Comparing the compositional and textural characteristics of these experimental products with the natural samples can be used to retrieve magma ascent conditions. These experimental simulations allow interpretation of direct observations and in situ measurements of syn-eruptive processes leading to more accurate forecasting of future eruptive scenarios.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Linking Geophysical and Geochemical Warning Signals to Magmatic Processes

A key objective in volcanology is to forecast eruptions, i.e. to establish when, where, and how an eruption will occur and what magnitude it will be. The prerequisite of such forecasting is to (i) detect reliable precursory signals of magma ascent to subsurface and (ii) anticipate the eruption style in order to inform the crisis management strategy. To reach these objectives, the intensification of the geophysical and geochemical signals associated with an unrest episode has to be interpreted in terms of magma movements. This is a far from trivial task because (i) seismicity has to distinguish signals related to magma movements from those of rock fracturing and/or gas percolation (see Chapter “Volcano Seismology: detecting unrest in wiggly lines”), (ii) ground deformation has to precisely track magma motion towards the surface (see Chapter “Volcano geodesy and multiparameter investigations”), and (iii) the flux and the speciation of emitted gas at the surface has to be interpreted in terms of magma ascent and degassing (see Chapter “Volcanic gases and low temperature volcanic fluids”). For any of these monitoring signals, their interpretation in terms of impending eruption requires knowing at what depth beneath the volcano magma is stored (magma storage conditions) and how it progresses toward the surface (magma ascent conditions). A pertinent approach to investigate the conditions of magma storage and ascent consists of comparing petrological and textural studies of previously erupted products to the results of experimental simulations carried out under realistic magma conditions. During the last decades the development of powerful analytical and experimental tools has led to great advances in this type of investigation. Of course, this is an a posteriori approach (using previously erupted products) that relies on considering past eruptive behaviour of a given volcanic system as a guide to future activity. For this reason, it is necessary to understand the fundamental magmatic processes at any particular volcano and in the long term, build up a record that links the pre-eruptive signals with eruptive products. In this way we can successfully use the warning signals to forecast or even start to predict the timing and style of an imminent eruption.

2 Magma Storage

How and where magma is stored before an eruption are enduring and complex questions, particularly given the range of hypotheses covering single versus multiple storage regions or dyke feeder systems. Key parameters in interpreting the precursory geophysical and geochemical signals are the depth of storage and the volatile content dissolved in the magma, as the exsolution of these provides an important driving force for explosive eruptions. Magma consists principally of phenocrysts (crystals larger than 50–100 µm) coexisting with a silicate melt containing dissolved volatile species (e.g. H2O, CO2, S species, F, Cl, etc.…). To assess the magma storage conditions, one has to determine the parameters (i.e. the pressure, temperature, redox state, volatile content) that govern equilibrium between melt and the phenocrysts. This is accomplished by comparing the phase assemblage and compositions of the natural products to those obtained by phase-equilibrium experiments where all these parameters are controlled.

2.1 Decoding Natural Pyroclasts

Phenocrysts. Mineral compositions are sensitive to various intensive (pressure, temperature, ƒO2) and extensive (host liquid composition and volatile content) variables. In some cases, the compositions can be used as geothermobarometers (or hygro/oxy/chemo-meters) to retrieve first-order parameters of crystallization. For instance, we can calculate crystallization temperature from the composition of orthopyroxene-clinopyroxene pairs (e.g. Lindsley and Andersen 1983) or amphibole-plagioclase pairs (e.g. Holland and Blundy 1994), temperature and oxygen fugacity from Fe–Ti oxide pairs (e.g. Ghiorso and Evans 2008) or pressure from amphibole composition (e.g. Ridolfi and Renzulli 2012). Such calculations require two main criteria: (i) the thermobarometers must have been calibrated experimentally for conditions and compositions relevant to those of the target samples and (ii) the analysed phenocrysts must be identified as part of the phenocryst assemblage in chemical equilibrium with the melt in the reservoir under pre-eruptive conditions. This can achieved by comparison with experiments that simulate a range of variables. Establishing different ‘equilibrium’ events also becomes crucial as magma mixing (and associated reheating prior to eruption or further crystallization outside the storage zone) very often blur the pre-intrusion/eruption equilibrium conditions. Moreover, many eruptions involve the entrainment of crystals that did not grow from the erupted magma and are consequently out of equilibrium with the melt in which they occur. These are often termed xenocrysts or antecrysts and increasingly recognised as important aspects of magma’s crystal cargo (e.g. Streck 2008; Kilgour et al 2013). The processes of mixing, reheating, and potentially decompression recorded in these crystals, may be used to provide timescales of reservoir dynamics, such as residence times between the last magma recharge and eruption (e.g. Saunders et al. 2012). Indeed, the compositional zoning of some phenocrysts witness cycles of recharge events prior to the final eruption (e.g. Druitt et al. 2012). Diffusion chronometry provides a means to infer the crystal residence time in the reservoir prior to eruption (e.g. Costa and Morgan 2010), but again requires experimental calibration of the rates involved under various conditions.

Glass inclusions. Glass (or “melt”) inclusions are aliquots of melt that are trapped in crystals, usually during stages of rapid crystal growth (Fig. 1a). If trapped in phenocrysts crystallizing in the magma chamber, these inclusions will be the only witness of the composition of the melt in equilibrium with the phenocrysts prior to eruption, provided that they remained sealed after entrapment (no volatile leak, no crystallization or post-entrapment interaction with the host mineral). Indeed, after leaving the storage region, the melt initially surrounding the phenocrysts is likely to degas and crystallize microlites upon ascent, therefore deviating significantly from its pre-eruptive composition and character. The two main objectives of studying glass inclusions in phenocrysts are (i) mineral-melt thermobarometry (clinopyroxene-melt or plagioclase-melt; e.g., Putirka 2008; Water and Lange 2015) and (ii) pre-eruption volatile contents and speciation that can be converted into gas saturation pressure using experimentally-derived volatile solubility laws and which represent an end-member in the calculations of the volcanic degassing budget (dissolved vs. released gases). This latter approach requires that the magma be demonstrably volatile-saturated at the time of melt inclusion entrapment, for example by looking at relationships between dissolved volatile contents and trace elements in inclusions (Blundy and Cashman 2008). If the magma was not saturated, the calculated pressure generally represents a minimum depth prior to volatile volatile-saturated, the calculated pressure generally represents a minimum pressure estimate. As an example, the glass inclusions in phenocrysts from pyroclasts of the last eruption of Morne aux Diables, Dominica, have been analysed by ion microprobe. The data show about 6 to 8 wt% dissolved H2O, up to 3000 ppm CO2, together with some chlorine and fluorine. Available H2O–CO2 solubility models based on experiments for comparable compositions (e.g. Tamic et al. 2001) indicate melt entrapment during phenocryst crystallization at pressures as high as 400–500 MPa (depth of <22 km) for sample DC139 and shallower depth for sample DC08 although it is also possible this magma originally contained even more CO2 than is recorded by any of the analysed melt inclusions. (Figure 1b). Small vesicles in the inclusions of Fig. 1a suggest there was exsolution of volatiles during ascent. The possible disequilibrium between such vesicles and melt produced during very rapid ascent is discussed in Chapter “Magma degassing: the diffusive fractionation model and beyond”.

Melt inclusion (MI) volatile contents from the Morne aux Diables complex (MAD), northern Dominica, as determined by ion-microprobe measurements. a Close up of inclusions shows they were either slightly vesiculated, during capture (fluid-saturated) or became so during ascent. The right hand crystal contains a very large melt inclusion around the bright oxide inclusions that has vesiculated more extensively, possibly due to cracks developing and exposing the melt to the full decompression effect during eruption. In b the maximum amount of H2O and CO2 that can be dissolved in a melt at any given depth follows pressure dependent isopleths that can be determined experimentally (in this case from Tamic et al. 2001). This represents the minimum pressure (depth of entrapment of a MI). These trends are controlled by the lower solubility of CO2 compared to H2O, such that there is a rapid drop in CO2 before H2O starts to be lost (coloured arrows)

Complexity of open-systems. An eruption is often triggered by the injection of new magma into the reservoir, which reheats, mingles, and mixes with the resident magma. Upon ascent to the surface, the two batches may interact to varying degrees and can further crystallize and cool. Therefore, imprudent use of geothermobarometers may yield large pressure and temperature ranges that cannot be easily reconciled with a single/specific episode of equilibrium crystallization. In order to retrieve the storage conditions of the resident magma, i.e. prior to deep magma mixing or before possible modification within the volcanic conduit, a detailed petrological study is necessary to identify precisely the different stages of perturbation and their characteristics in terms of phase assemblage and chemical composition. Experimental petrology is one of the tools that helps to unravel the various magmatic processes at work and their relative impact on magma chemistry and magmatic evolution.

2.2 Phase-Equilibrium Experiments

Phase-equilibrium experiments use natural (or analogue) products as starting material that are subjected to high-pressure (HP) and high-temperature (HT) in various devices under controlled conditions of pressure, temperature, oxygen fugacity, and volatile content. Such experiments are powerful tools to simulate realistic magmatic conditions for the crustal reservoirs that feed volcanic systems. Experimental equipment ranges from cold-seal pressure vessels, internally-heated pressure vessels, and piston-cylinder apparatus, depending on the investigated conditions. The principle is to reproduce the natural assemblage, proportion, and chemical compositions of the phenocrysts and equilibrium coexisting melt in the magma storage region. This is then compared with the natural samples in order to retrieve the pre-eruptive crystallization conditions (Fig. 2).

Phase equilibrium experiments for the Tungurahua 2006 andesite, showing a mineral stability fields as a function of temperature and H2O content at 200 MPa and oxidizing conditions (fO2 = NNO + 0.8 log unit). SEM images of the experimental charges are shown in b for 1000 °C and H2O saturation (~6.1 wt% H2O dissolved in melt), c 975 °C and ~5.7 wt% H2O, and d 975 °C and 5.2 wt% H2O. Note the drastic increase of crystal content with cooling or dehydration; gl for glass (L for silicate liquid), ol for olivine, cpx for clinopyroxene, opx for orthopyroxene, pl for plagioclase, amph for amphibole, mag for magnetite, and ilm for ilmenite

The first prerequisite for such an approach is a detailed petrological and mineralogical study of the erupted samples in order to identify the magmatic processes potentially perturbing equilibrium crystallization in the reservoir. Indeed, the relevance of the experimental study relies on accurate petrological knowledge that dictates the choice of the starting material and run procedure (Pichavant et al. 2007). The second prerequisite is the appropriate choice of the volatile species (H2O, CO2, sulphur, etc.) and contents to be added to the starting material. These dissolved volatiles can impact crystallization (sequence, mineral stability fields, and phase compositions; Scaillet and Pichavant 2003; Riker et al. 2015). Where volatile measurements on melt inclusions are available, these can be used, although it is possible that the melt inclusions may no longer be representative of the initial volatile content (e.g. due to possible leakage or recrystallization). Consequently, volatile species and contents become experimental parameters that have to be varied within a range that is first inferred from the study of the glass inclusions (when available), and/or based on previous work carried out on similar bulk rock compositions. It should be remembered that entrapment of melt inclusions requires crystallisation to occur and magmas may undergo substantial volatile loss (degassing) prior to any crystallisation. For instance, Blundy et al. (2010) speculate that many magmas had original CO2 contents significantly higher than those recorded by any melt inclusions.

It is clear that an approach involving the combination of petrological study of the natural products and phase-equilibrium experiments can help to retrieve the storage conditions of magmas of a wide range of compositions. This is a prerequisite step for the interpretation of unrest signals and construction of eruptive scenarios.

3 Magma Ascent

During ascent in the volcanic conduit the silicate melt around the phenocrysts degasses by exsolving its dissolved volatiles as gas bubbles. This may lower the liquidus triggering the crystallization of microlites (i.e. crystals smaller than about 50–100 µm). The residual melt is transformed both chemically, by degassing and differentiation as microlites crystallize and physically, by an increase in melt viscosity and a change from a single liquid phase to a three-phase suspension (i.e. liquid, gas bubble, and microcrystals). Both types of transformations have drastic effects on the bulk magma flow conditions (rheology) that control ascent rate and the ductile versus brittle behaviour of the magma.

The rate of magma decompression/ascent is the key parameter that controls the kinetics of degassing and crystallization, and ultimately, the eruptive style. In silicic to intermediate systems, slow ascent rates typical of effusive eruptions such as lava flow or dome growth, i.e. cm/s to mm/s (Gardner and Rutherford 2000) yield timescales long enough for extensive degassing and crystallization. In contrast, the high ascent rates prevalent during paroxysmal Strombolian or Plinian eruptions (i.e. of the order of m/s; Gardnerand and Rutherford 2000) are able to generate physico-chemical disequilibria of both degassing and crystallization processes, driving gas overpressures that may be released explosively.

3.1 Textures of Natural Pyroclasts

Decompression-induced degassing of the magma creates gas bubbles, the number density of which has been demonstrated to correlate with the decompression rate simulated by experiments (Mourtada-Bonnefoi and Laporte 2004; Mangan et al. 2004). The growing bubbles can rapidly coalesce and form gas escape channels. In this case, the bubble number densities in the erupted/quenched pyroclasts may no longer be representative of the initial ascent rates under which nucleation was triggered. The timescale of outgassing by magma foam collapse varies from a couple of hours to about 1000 h for magmas having bulk viscosities of ~104 to 105.5 Pa.s, respectively (Martel and Iacono-Marziano 2015). This restricts the use of the degassing process to simulations of rapid magma ascent rates such as those during Plinian events. To investigate longer transit times in the conduit, one requires information from magmatic processes with timescales longer than degassing. Microlite crystallization is one of those processes, because diffusion in the melt, that controls crystal growth, occurs on timescales ranging from hours in mafic melts, to days in silicic melts. Microlite number density, volume proportion, size and shape have all been used as markers of the undercooling (liquidus temperature minus magma temperature) that drives crystallization (e.g. Hammer et al. 1999); the higher the undercooling, the more numerous, smaller, and irregularly-shaped the crystals. With decompression (and dehydration of the melt), liquidus temperature increases (as does undercooling), so that it becomes possible to infer the depth of crystallization in the conduit by relating the textural characteristics of the microlites to undercooling and pressure (Fig. 3). This approach has been used by Melnik et al. (2011) to constrain both magma flow and reservoir shape for the 1980–86 dome-forming eruptions of Mount St. Helens (USA). Such modelling requires an accurate determination of the dependence of undercooling on pressure, which can be achieved through decompression experiments (e.g. Riker et al. 2015).

Relationships between effective undercooling (ΔTeff; in green) and microlite textural characteristics in a H2O-saturated rhyolitic melt (modified after Mollard et al. 2012). Plagioclase microlites crystallized at 150 MPa after an isothermal quasi-instantaneous decompression from 200 MPa, i.e. ΔTeff = 50 °C, are represented by scarce large tabular crystals. With decreasing pressure and increasing ΔTeff, microlites become more numerous, but smaller in size, and they show more complex shapes ranging from skeletal (hollow) to dendritic

3.2 Dynamic Experiments

Dynamic experiments, such as decompression, deformation or shock-wave experiments, are valuable tools to investigate degassing, crystallization, strain, mixing, or fragmentation of a magma. They provide information on the physics, chemistry, and kinetics of syn-eruptive magmatic processes, which can be used in turn to decode natural pyroclast formation in order to better identify geophysical and geochemical precursory signals of an eruption. Shock-wave experiments dedicated to the fragmentation process are covered in Chapter “From unrest to eruption: Conditions for phreatic versus magmatic activity”; the discussion below concentrates on decompression and deformation experiments.

Decompression experiments performed at elevated pressure (HP) and temperature (HT) have proved useful in accurately simulating magma ascent in volcanic conduits (e.g. Hammer and Rutherford 2002). In particular, experimental decompression rates can cover the most of the perceived range of magma ascent rates during volcanic eruptions. For instance, Plinian ascent rates of the order of m/s can be simulated experimentally by decompression durations from seconds to hours whereas the slow ascent rates recorded for dome eruptions can be reproduced by decompression durations of several days or weeks. More generally, decompression experiments can simulate different natural eruptive scenarios depending on the applied decompression rate, final pressure, and dwell time at final pressure. In basaltic H2O- and CO2-bearing magmas, experimental decompression in the duration range of <1–10 h has provided information on degassing processes leading to either regular or paroxysmal Strombolian eruptions (Chapter 15 “Magma degassing: the diffusive fractionation model and beyond”). In silicic melts, decompression pathways and durations from ten seconds to forty days have been investigated experimentally to evaluate the lifetime of rhyolitic foams as a function of bulk viscosity (Martel and Iacono-Marziano 2015). Deformation experiments performed in vessels equipped with torsion or coaxial deformation modules have shown that the lifetime of such magmatic foams is drastically reduced when a differential stress field prevails, because it enhances bubble coalescence (e.g. Okumura et al. 2009). The recent implementation of HP-HT devices that allow magma deformation at pressure coupled with in situ measurements of permeability, represents a considerable step forward for investigating the explosive-effusive transition of volcanic eruptions in the laboratory under realistic conditions (Kushnir et al. 2017).

Figure 4 illustrates how timescales of degassing and crystallization during decompression can be used to decipher eruption style. Magmas from both, Plinian and dome-forming eruptions (dome, block-and-ash flows, surges), degas during ascent. However, gases in dome-forming magmas escape from the melt (leading to dense pyroclasts) whereas Plinian foams have no time to collapse through gas escape (leading to pumiceous pyroclasts) which suggests Plinian ascent durations are limited to a couple of hours (Martel and Iacono-Marziano 2015). Furthermore, in contrast to Plinian magmas, dome-forming magmas have time to crystallize during ascent. At Mt. Pelée, the moderately-explosive block-and-ash flows in 1929–1932 may have degassed and crystallized continuously during an ascent lasting more than 3–6 days, so that little gas overpressure remains at dome level. In contrast, the devastating surges in 1902 may have resulted from rapid ascent (i.e. <3 days) that did not allow crystallization in the conduit, followed by extensive microlite crystallization at dome level (due to large effective undercooling). The exsolving gas and high overpressurization resulting from this extensive crystallization may have triggered the violent surges (Martel 2012).

Deciphering eruption explosivity from decompression-induced degassing and crystallization experiments (see text) [Photograph of Redoubt is from R. Clucas (USGS), Mt. Pelée is from Lacroix (1904), and Merapi comes from the website: gunungmerapi.weebly.com]

This application of decompression experiments highlights the possibility of forecasting the style of an eruption provided the magma ascent rate towards the surface can be determined by some remote means (seismology, gravity, geodesy, gas discharge).

4 Future Directions

The combination of equilibrium and dynamic experiments can simulate many of the conditions relevant to magma eruption, because realistic pressures, temperatures and rates of decompression or shear are now accessible in the laboratory. The one parameter that remains impossible to simulate is an extended timescale. Experiments last typically a maximum of weeks, or occasionally months. In practical terms, this leads to small crystal sizes compared with nature, occasional difficulties in establishing equilibrium, or very short diffusion profiles for controlled ‘disequilibrium’ experiments. However, as new analytical techniques are developed we can start to make nanoscale measurements that allow us to measure profiles developed on laboratory timescale, providing access to ever faster natural processes (Saunders et al. 2014; Lloyd et al. 2014).

Development of in situ observation or measurement techniques represents a major step forward in the understanding of the magmatic processes linked to volcanic eruptions. It is becoming possible to make in situ observations using cameras coupled to HP-HT vessels equipped with transparent windows (e.g. Gondé et al. 2011) or 4D in situ X-ray tomography (e.g. Pistone et al. 2015). HP-HT vessels coupled with in situ analytical techniques are already capable of measuring the volatile species either dissolved in the melt under pressure by in situ spectroscopy techniques (Raman or Infrared) or exsolved as vapour. Laboratory simulation of magma degassing and crystallization with these new in situ approaches will allow the identification of potential geophysical and geochemical signals that may be used as unrest precursors.

References

Blundy JD, Cashman KV (2008) Petrologic reconstruction of magmatic system variables and processes. Miner Inclusions Volcanic Proc 69:179–239

Blundy JD, Cashman KV, Rust AC, Witham F (2010) A case for CO2-rich arc magmas. Earth Planet Sci Lett 290(3–4):289–301

Costa F, Morgan D (2010) Time constraints from chemical equilibration in magmatic crystals. In Dosseto A, Turner SP, Van Orman JA (eds) Timescales of magmatic processes: from core to atmosphere. Wiley-Blackwell, pp 125–159

Druitt TH, Costa F, Deloule E, Dungan M, Scaillet B (2012) Decadal to monthly timescales of magma transfer and reservoir growth at a caldera volcano. Nature 482:77–80

Ghiorso MS, Evans BW (2008) Thermodynamics of rhombohedral oxide solid solutions and a revision of the Fe-Ti Two-oxide geothermometer and oxygen-barometer. Am J Sci 308:957–1039

Gondé C, Martel C, Pichavant M, Bureau H (2011) In situ bubble vesiculation in silicic magmas. American Mineralogy 96:111–124

Hammer JE, Cashman KV, Hoblitt RP, Newman S (1999) Degassing and microlite crystallization during pre-climactic events of the 1991 eruption of Mt. Pinatubo Philippines. Bull Volcanol 60:355–380

Hammer JE, Rutherford MJ (2002) An experimental study of the kinetics of decompression-induced crystallization in silicic melts. J Geophys Res 107(ECV8):1–23

Holland T, Blundy JD (1994) Non-ideal interactions in calcic amphiboles and their bearing on amphibole-plagioclase thermometry. Contrib Miner Petrol 116(4):433–447

Kilgour GN, Blundy JD, Cashman KV, Mader HM (2013) Small volume andesite magmas and melt-mush interactions at Ruapehu, New Zealand: evidence from melt inclusions. Contrib Minerology Petrol 166(2):371–392

Kushnir ARL, Martel C, Champallier R, Arbaret L (2017) In situ confirmation of permeability development in shearing bubble-bearing melts and implications for volcanic outgassing. Earth Planet Sci lett 458:315–326

Lacroix A (1904) La Montagne Pelée et ses éruptions. Masson Paris, p 662

Lindsley DH, Andersen DJ (1983) A two-pyroxene thermometer. J Geophys Res 88(S02):001. doi:10.1029/JB088iS02p0A887

Lloyd AS, Ruprecht P, Hauri EH, Rose W, Gonnerman HM, Plank T (2014) NanoSIMS results from olivine-hosted melt embayments: magma ascent rate during explosive basaltic eruptions. J Volcanol Geoth Res 283:1–18

Mangan MT, Sisson TW, Hankins WB (2004) Decompression experiments identify kinetic controls on explosive silicic eruptions. Geophys Res Lett 31:L08605. doi:10.1029/2004GL019509

Martel C (2012) Eruption dynamics inferred from microlite crystallization experiments: application to Plinian and dome-forming eruptions of Mt. Pelée (Martinique, Lesser Antilles). J Petrol 53:699–725

Martel C, Iacono-Marziano G (2015) Bubble coalescence, outgassing, and foam collapsing in decompressed rhyolitic melts. Earth Planet Sci Lett 412:173–185

Melnik OE, Blundy JD, Rust AC, Muir DD (2011) Subvolcanic plumbing systems imaged through crystal size distributions. Geology 39(4):403–406

Mollard E, Martel C, Bourdier J-L (2012) Decompression-induced crystallization in hydrated silica-rich melts: Empirical models of experimental plagioclase nucleation and growth kinetics. J Petrol 53:1743–1766

Mourtada-Bonnefoi CC, Laporte D (2004) Kinetics of bubble nucleation in a rhyolitic melt: an experimental study of the effect of ascent rate. Earth Planet Sci Lett 218:521–537

Okumura S, Nakamura M, Takeuchi S, Tsuchiyama A, Nakano T, Uesugi K (2009) Magma deformation may induce non-explosive volcanism via degassing through bubble networks. Earth Planet Sci Lett 281:267–274

Pichavant M, Costa F, Burgisser A, Scaillet B, Martel C, Poussineau S (2007) Equilibration scales in silicic to intermediate magmas—implications for experimental studies. J Petrol 48:1955–1972

Pistone M, Arzilli F, Dobson KJ, Cordonnier B, Reusser E, Ulmer P, Marone F, Whittington AG, Mancini L, Fife JL, Blundy JD (2015) Gas-driven filter pressing in magmas: insights into in-situ melt segregation from crystal mushes. Geology 43:699–702

Putirka KD (2008) Thermometers and barometers for volcanic systems. Rev Mineral Geochim 69:61–120

Ridolfi F, Renzulli A (2012) Calcic amphiboles in calc-alkaline and alkaline magmas: thermobarometric and chemometric empirical equations valid up to 1130 °C and 2.2 GPa. Contrib Mineral Petrol 163:877–895

Riker JM, Blundy JD, Rust AC, Botcharnikov RE, Humphreys MCS (2015) Experimental phase equilibria of a Mount St. Helens rhyodacite: a framework for interpreting crystallization paths in degassing silicic magmas. ContribMineral Petrol 170(6):535–560. doi:10.1007/s00410-015-1160-5

Rutherford MJ, Gardner JE (2000) Rates of magma ascent. In: Sigurdsson H (ed) Encyclopedia of volcanoes. Academic San Diego, California, pp 207–217

Saunders KE, Blundy JD, Dohmen RG, Cashman KV (2012) Linking petrology and seismology at an active volcano. Science 336(6084):1023–1027

Saunders K, Buse B, Kilburn MR, Kearns S, Blundy JD (2014) Nanoscale characterisation of crystal zoning. Chem Geol 364:20–32

Scaillet B, Pichavant M (2003) Experimental constraints on volatile abundances in arc magmas and their implications for degassing processes. In: Oppenheimer C, Pyle D, Barclay J (eds) Volcanic degassing. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 213, 23–52

Streck MJ (2008) Mineral textures and zoning as evidence for open system processes. Rev Mineral Geochem 69:595–622

Tamic N, Behrens H, Holtz F (2001) The solubility of H2O and CO2 in rhyolitic melts in equilibrium with a mixed CO2-H2O fluid phase. Chem Geol 174:333–347

Waters LE, Lange RA (2015) An updated calibration of the plagioclase-liquid hygrometer-thermometer applicable to basalts through rhyolites. Am Miner 100:2172–2184

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Martel, C., Brooker, R.A., Andújar, J., Pichavant, M., Scaillet, B., Blundy, J.D. (2017). Experimental Simulations of Magma Storage and Ascent. In: Gottsmann, J., Neuberg, J., Scheu, B. (eds) Volcanic Unrest . Advances in Volcanology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/11157_2017_20

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/11157_2017_20

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-58411-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-58412-6

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)