Abstract

The discovery of rapid synthesis of complex organic solids in the late stages of stellar evolution has led to a new realization that carbonaceous compounds can be a major significant component of interstellar dust. Signatures of aromatic and aliphatic solids are seen in interstellar clouds as well as the diffuse interstellar medium. Similar features are also seen in the integrated spectrum of galaxies. This has raised the possibilities that many of the unidentified astronomical phenomena such as the diffuse interstellar bands, the 217 nm feature, the extended red emission, the 21 and 30 μm emission features, could also arise from complex organics. In this paper, we discuss the possible chemical structures of these organic solids and the relationships between circumsmtellar and interstellar dust with the organics found in meteorites, asteroids, comets and planetary satellites. The possibility that all these organics share a common origin is discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

1. Introduction

While the existence of dark clouds in the Milky Way has been suspected of due to intervening obscuring masses in space (Barnard, 1919), the confirmation of the presence of interstellar dust only came after the observation of selective extinction of star light (Ö pik, 1931). Since micron-size solid particles preferentially absorb and scatter blue light more than red light, their presence can be inferred by their effect on the colors of background stars. Many stars on the galactic plane appear redder in color than expected from their respective spectral types based on their photospheric spectra. The degree of extinction can be quantified by the difference between the observed and expected intrinsic colors of the stars and the amount of extinction as a function of wavelength is known as the extinction curve. Based on the shapes of the extinction curves in different directions, early speculations on the chemical makeup of interstellar solids include metals (e.g., iron), ice, graphite, and diamond, etc. The first spectroscopic feature detected was the 217 nm UV feature, leading to the suggestion of graphite as the carrier of the feature. The real breakthrough in the study of the chemical nature of interstellar dust only came after the development of infrared spectroscopy, where amorphous silicates are identified as a major ingredient of interstellar solid particles due to their absorption features at 9.7 and 18 μm. Nowadays, interstellar dust can be observed as the result of absorption, scattering, self absorption, and emission of radiation with both imaging and spectroscopic studies. Figure 1 shows a direct 5.8 μm imaging of dust emission in the Eagle Nebula obtained with the Infrared Array Camera of the Spitzer Space Telescope.

Solid-state particles are not confined to clouds in the interstellar medium. Now dust is found in circumstellar environments (both young and old stars), interplanetary space, diffuse galactic medium, external galaxies, and intergalactic space. Spectral energy distribution of active galaxies show that fluxes emitted by the solid-state component accounts for a significant fraction of the total energy output of galaxies (Fig. 2). Submillimeter-wave photometry has detected dust emission in quasars of z ~ 6, showing that solids were already present in the very early Universe (Leipski et al., 2010).

A typical spectral energy distributions (SED) of starburst galaxies consists of two major components: an optical component (peaking at ~0.4 μm) due to photoionized gas and an infrared component (peaking at ~100 μm) due to dust. The narrow features are atomic lines and the broad features between 5 and 20 μm marked as AIB are due to aromatic compounds. Figure adapted from Groves et al. (2008).

For the past century, the studies of interstellar dust have been focussed on answering these questions:

-

composition: what is the exact chemical composition of solids in the different environments? This in principle can be addressed by spectroscopy

-

distribution: how are these grains distributed in space? This question is most effectively answered by wide-field imaging

-

abundance: what is the dust to gas ratio and how much of the specific heavy elements are tied up in the solid state?

-

effects: what are the radiative interactions between dust and gas?

-

synthesis: how do these solids condense from the gasphase atoms and molecules?

With the discovery of circumstellar and interplanetary dust, questions on interstellar dust can be broadened to include their relationship between the circumstellar, interstellar, and Solar System solid particles. Do they share similar chemical compositions, or more significantly, do they have a common origin? These are the questions that we will address in this paper.

2. Spectroscopic Identification of Solids

In a solid, rotational motions are not possible and the vibrational-rotational transitions seen in gas-phase molecular spectra are replaced by a broad, continuous band at the vibrational frequencies. A crystalline solid has a highly ordered lattice structure, with constant bond lengths and angles between atoms. Due to the symmetry of the structure, only a few of the possible lattice vibrational modes are optically active. Therefore, crystalline solids have only a few sharp features in the infrared. In contrast to crystalline solids, amorphous solids have their atoms arranged in a disordered manner. While the bond lengths in amorphous solids are nearly the same, the bond angles can have large variations. This lesser degree of symmetry results in most modes being optically active. The variation of bond lengths and angles also mean that there is a wider range of vibrational frequencies, leading to broader features (Kwok, 2007). By comparing the absorption spectra of terrestrial minerals to observed astronomical spectra, we can identify the chemical composition of solids in space. The best known example is the identification of amorphous silicates through their Si–O stretching mode at 9.7 μm and the Si–O–Si bending mode at 18 μm (Kwok et al., 1997). Crystalline silicates (olivines and pyroxenes) as well as several refractory oxides have been similarly identified (Jäger et al., 1998).

3. Organic Solids on Earth

Organic matter on Earth is dominated by products of life. The total biomass in the biosphere is about 2000 Gt. Fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and gas, representing remnants of living matter in the past, add up to ~4 000 Gt. The largest amount of organic matter is actually in the form of kerogen (15 000000 Gt) (Falkowski et al., 2000). Kerogen is a solid sedimentary, insoluble, organic material found in the Earth upper crust. Its chemical structure is represented by random arrays of aromatic rings linked by long, aliphatic chains. The infrared spectrum of kerogen is characterized by C-H stretches of the methyl and methylene groups at 3.4 μm, strong plateaus at 8 and 12 μm, and various aromatic features due to C-H and C-C stretching and bending modes (Papoular, 2001).

There are also other artificial forms of organic solids produced by human activities. The most common example is soot, which is a product of combustion. Soot particles are spheroids of sizes 10–30 nm consisting of C and H atoms in mixed sp2/sp3 hybridizations. The exact chemical composition of soot is dependent on the mix of precursor gas and the density and temperature of the flame.

4. Synthesis of Organic Solids in the Late Stages of Stellar Evolution

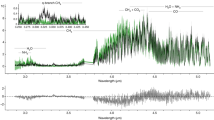

It is interesting to note that the conditions of stellar winds of asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars are similar to those for soot formation. In a carbon-rich AGB star, molecules such as C2, C3, CN, HCN, HC3N, HC5N, and C2H2 are formed in the stellar wind. Over 60 different kinds of molecules have been detected through their rotational or vibrational transitions in the circumstellar regions of AGB stars (Ziurys, 2006). Observations of AGB stars and their descendents proto-planetary nebulae and planetary nebulae have revealed the gradual formation of diacetylene (C4H2), triacetylene (C6H2), and benzene (C66). Emission features arising from the stretching and bending modes of aromatic (at 3.3, 6.2, 7.7, 8.6, 11.3 μm, collectively known as the aromatic infrared bands, or AIB) and aliphatic (3.4 and 6.9 μm) structures also emerge during this phase (Fig. 3). The infrared spectra of proto-planetary nebulae display broad emission plateaus at 8 and 12 μm, which probably originate from a collection of different in-plane and out-of-plane bending modes of aliphatic groups attached to aromatic rings (Kwok et al., 2001). There is evidence that the chemical structure becoming more aromatic as the star evolves from proto-planetary nebulae to planetary nebulae, probably as the result of photochemistry. The combination of the AIBs and emission plateaus suggests that the carrier is a kerogen-like organic solid (Guillois et al., 1996).

ISO SWS01 spectra of the young planetary nebula IRAS 21282+5050 and the proto-planetary nebula IRAS 07134+1005, showing various aromatic C-H and C-C stretching and bending modes at 3.3, 6.2, 7.7, 8.6, and 11.3 μ m. The PPN spectra are characterized by the 12.1, 12.4, 13.3 μ m out-of-plane bending mode features from small aromatic units. The sharp rise to 20 μ m in the spectrum of IRAS 07134+1005 is due to the unidentified 21 μ m feature.

The most significant fact in the detection of complex organics in the late stages of stellar evolution is the rapid speed of synthesis. The dynamical time of stellar winds in AGB stars is ~103 yr. The evolution age of proto-planetary nebulae is ~103 years and the lifetimes of planetary nebulae is about 20 000 to 40 000 yr. The detection of the aromatic and aliphatic compounds during these phases of stellar evolution shows that complex organic solids can be rapidly synthesized under low-density conditions (Kwok, 2004).

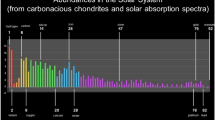

5. Organic Solids in the Solar System

In spite of the common perception that Solar System objects consist primarily of metals, minerals, and ices, in fact complex organics are widely present in the Solar System. Laboratory analysis of carbonaceous meteorites have shown that the majority of organic matter in these objects is in the form of insoluble macromolecular organic matter (IOM). Gas chromatography has characterized IOM as predominantly aromatic with aliphatic functional groups (Kerridge, 1999). X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy of interplanetary dust particles (IDP) has revealed similar structures in IDPs (Flynn et al., 2003). Rather than just “dirty snow balls”, comets are now found to have organic refractory materials consisting of H, C, N, O in the nucleus. Samples of Comet Wild 2 returned by the STARDUST mission have also found organic contents similar to IOM (Sandford et al., 2006). Although there is no good spectroscopic observations or sample return from asteroids, the red colors of asteroids are also suggestive of organic substance on the surface (Cruikshank et al., 1998). In planetary satellites, the Cassini-Huygens mission has found tholins-like materials in the atmosphere and on the surface of Titan (Nguyen et al., 2007). The amount of carbon in the form of methane in the Titan atmosphere is estimated to be 360 000 Gt, while the amount of carbon in liquid form (ethane and methane) in lakes is 16 000–160000 Gt. However, the greatest amount is in organic solids contained in sand dunes, with an inventory of 160000–640000 Gt (Lorenz et al., 2008). This is much larger than the total sum of organics on Earth (Section 3).

6. Organic Solids as Carriers of Unidentified Phenomena

Almost a century after discovery, the origin of the diffuse interstellar bands (DIB) is still not known (Sarre, 2006). This class of over 300 interstellar absorption bands seen in the spectra of background stars have too broad a profile to be due to atomic lines, and are most likely of molecular or solid-state origin. The 217 nm feature, a prominent absorption feature in the extinction curve, was first found in 1965 but its carrier is still not identified. The fact that the 217 nm feature can be seen in galaxies as distant as z > 2 (Eíiasdóttir et al., 2009) suggests that its carrier is synthesized in the early Universe. The extended red emission (ERE) is a broad (Δλ ~ 80 nm) band in the visible seen in the circumstellar, diffuse interstellar, and galactic haloes in emission. The ERE is probably the result of photoluminescence but the carrier is not known (Smith and Witt, 2002). More recently, the 21 and 30 μ m emission features are found in proto-planetary nebulae and planetary nebulae, with the 30 μ m feature emitting up to 20% of the total flux of these objects (Hrivnak et al., 2000).

The ERE, 21, and 30 μ m features are known to be associated with carbon-rich objects and it is reasonable to assume that their carriers are carbon based. The large number of DIBs also suggests an organic nature of the carrier as only carbon atoms have the rich chemistry needed to create the large variety of features (Snow and McCall, 2006). The idea of organic solids as a component of the interstellar dust and as potential carrier of these phenomena was discussed by Papoular et al. (1996). The most likely reason why we have been unable to identify the origin of these phenomena is because their carriers have no natural counterparts in the terrestrial environment and the solution of these mysteries may rely on the artificial production of new kinds of organic compounds.

7. Amorphous Organic Solids

It is commonly believed in the astronomical community that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) molecules are responsible for the emission of the AIBs. PAH molecules are pure ring molecules made up of C and H. Their vibrational bands are well determined in the laboratory. Since they are simple molecules, their vibrational bands are sharp and the peak wavelengths well defined. These properties are greatly different from the observed profiles in astronomical spectra. In order to fit the observed spectra, proponents of the PAH hypothesis have to appeal to a complex mixture of PAHs of different sizes, structures (compact, linear, or branched) and charged states (neutrals, positive and negative ions). Since PAH molecules require UV photons to be excited, they cannot explain the wide presence of AIBs in reflection nebulae and proto-planetary nebulae where there is no UV background radiation. In order to account for these facts, the PAH hypothesis has to be revised to include larger sizes and other ionization states.

In spite of their well-known rotational and vibrational frequencies, not a single PAH molecule has yet been identified in space. A more plausible explanation to the AIBs is that they are emitted by complex organic solids of disorganized structure. These solids have natural broad emission profiles, and the features often sit on even broader emission plateaus of several microns in width. The observed spectral properties of AIBs are much closer to those of quenched carbonaceous composites, coal, kerogen, petroleum fractions, and other amorphous organic solids. In order for these organic particles to radiate efficiently in the near infrared, they probably have to be of nanometer size. Studies of nanometer-size solids with mixed sp2/sp3 structures should be further pursued in the laboratory.

In the space science community, tholins (Sagan and Khare, 1979) are the most discussed organic compounds in asteroids and Titan. Tholins are refractory organic materials formed by UV photolysis of reduced gas mixtures under cold plasma conditions. They share some commonality with HCN polymers (Matthews and Minard, 2006) in that they are both complex organic solids rich in N. What tholins, HCN polymers, and kerogen-like materials seen in proto-planetary nebulae have in common is that they are all amorphous carbonaceous compounds. If one applies energy to a mixture of organic molecules, amorphous organic structures similar to tholins or tar are the most likely products. It is therefore not surprising that nature is able to make amorphous organic solids with ease.

The origin of organic solids in the Solar System is still under debate. Many in the space science community take the position that these organics were made after the formation of the Solar System. The tholins-like materials on the surface of Titan is believed to have condensed from organic aerosols in the atmosphere, which in turn are formed from organic gas molecules through chemical reactions in the atmosphere. However, comets are formed in the coldest regions of the Solar System and are not expected to have undergone significant thermal or chemical processing until they venture into the inner Solar System. The detection of D and 15N enrichment in the organics collected from Wild 2 by STARDUST suggests that some particles may be of presolar origin (Sandford et al., 2006). Isotopic measurements of IDPs have shown evidence for deuterium enrichment, with D/H values as high as 50 times the Solar System values being found (Messenger, 2000). These results suggest that these IDPs contain remnants of interstellar materials which survived the formation of the Solar System. The elevated ratios of 15N/14N and D/H in organic globules in the Tagish Lake meteorite provides additional evidence that interstellar organics are present in the Solar System (Nakamura-Messenger et al., 2006). All these pieces of evidence suggest that at least some of the organics current present in the Solar System are remnants of interstellar materials inherited from our parent molecular cloud.

Organic solids are seen in interstellar clouds (e.g., molecular clouds surrounding sites of star formation) and diffuse interstellar medium. Do these organics form in situ from gas-phase molecules? Since all we have is a snap-shot of the chemical make-up of these clouds at the present time, there is no information on how these compounds are formed. The only concrete evidence of the formation of organic solids is in the circumstellar environment, where we know, e.g., in the late stages of stellar evolution, complex organics are synthesized on thousand year, or even hundred year, time scales.

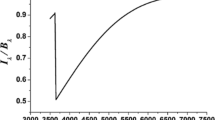

The most dramatic demonstration of the ease of condensation of organic dust can be found novae. Figure 4 shows that dust condensation took place within period of less than one month (Lynch et al., 2008). The AIB features are detected in the classical nova V705 Cas, with detected features at 3.28, 3.4, 8.1, 8.7, and 11.4 μm, where the 8.1 and 11.3 μm features are attributed by the observers as shifted 7.7 and 11.3 μm features respectively (Evans et al., 1997). When the first infrared spectrum was taken at day 157 after outburst, the 8.2 μ m feature is already present. Figure 5 shows the profiles of the 3.3, 3.4, 8.2, and 11.4 μ m features at 253 and 320 days after outburst. The signatures of organic dust is unmistakable.

IRTF SpeX spectra of V2362 Cyg on 2006 November 30 and 2006 Dec 21, showing a dramatic change from an ionized gas spectrum to a dust dominated spectrum in less than a month. The dust component has a color temperature of 1410±15 K. Figure adapted from Lynch et al. (2008).

Profiles of the 3.3 and 3.4 μ m features (left) and the 8.2 μm and 11.4 μ m features (right) of Nova V705 Cas at two different epochs (253 and 320 days after outburst, shown as solid and broken lines respectively). These detections show that organic solids can condense easily from the gas phase in the circumstellar envirnoment. Figure adapted from Evans et al. (2005).

Given the fact that organic solids are formed in large quantities in the late stages of stellar evolution, and almost every star with initial mass less than 8 M⊙ go through the AGB-PPN-PN evolution, one may speculate on whether the synthesis and ejection of organics by evolved stars can supply the organics seen in the interstellar medium. We know that inorganic grains such as SiC of AGB origin have been found in meteorites (Zinner, 1998), so there is evidence that stellar grains can survive the journey through the interstellar medium to have arrived in the Solar System. Could the stellar organics make the same journey? Instead of organic synthesis taking place separately and independently in circumstellar, interstellar, and Solar System, could they all share the same common origin?

8. Conclusions

Astronomical spectroscopic observations have unequivocally detected the presence of inorganic minerals such as amorphous silicates in circumstellar, interstellar, and galactic environments. These oxygen-based solids no doubt play an important role in the chemical makeup of the solid-state component of our own and other galaxies. We propose that carbon-based grains are equally, if not more prevalent, in the Universe. Recent astronomical and Solar System observations have shown that complex organic matter is widely present in the planetary, stellar, interstellar, and galactic environments. We now have evidence that organics of aromatic and aliphatic structures are being made efficiently and on a large scale by stars. These organic stellar materials are ejected into the interstellar medium, and may have reached the early Solar System. Bombardment by comets and asteroids during the early age of the Earth might have brought some of these primordial organics to Earth (Kwok, 2009).

The exact chemical structures of these organic solids are not known. They are most likely of amorphous structure with a mixed sp2/sp3 hybridization. It is possible that there exist yet unknown forms of organic solid that are responsible for the unexplained phenomena such as the 217 nm feature, the DIB, the ERE, and the 21 and 30 μ m features. Further laboratory studies are needed for us to make further progress in these puzzles.

References

Barnard, E. E., On the dark markings of the sky, with a catalogue of 182 such objects, Astrophys. J., 49, 1–24, 1919.

Cruikshank, D. P., T. L. Roush, M. J. Bartholomew, T. R. Geballe, Y. J. Pendleton, S. M. White, J. F Bell, J. K. Davies, T. C. Owen, C. De Bergh, D. J. Tholen, M. P. Bernstein, R. H. Brown, K. A. Tryka, and C. M. Dalle Ore, The composition of centaur 5145 pholus, Icarus, 135, 389–407, 1998.

Elíasdóttir, Á., J. P. U. Fynbo, J. Hjorth, C. Ledoux, D. J. Watson, A. C. Andersen, D. Malesani, P. M. Vreeswijk, J. X. Prochaska, J. Sollerman, and A. O. Jaunsen, Dust extinction in high-z galaxies with gamma-ray burst afterglow spectroscopy: The 2175Å feature at z = 2.45, Astrophys. J., 697, 1725–1740, 2009.

Evans, A., T. R. Geballe, J. M. C. Rawlings, S. P. S. Eyres, and J. K. Davies, Infrared spectroscopy of Nova Cassiopeiae 1993. II—evolution of the dust, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc, 292, 192, 1997.

Evans, A., V. H. Tyne, O. Smith, T. R. Geballe, J. M. C. Rawlings, and S. P. S. Eyres, Infrared spectroscopy of Nova Cassiopeiae 1993—IV. A closer look at the dust, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc, 360, 1483–1492, 2005.

Falkowski, P., R. J. Scholes, E. Boyle, J. Canadell, D. Canfield, J. Elser, N. Gruber, K. Hibbard, P. Högberg, S. Linder, F. T. Mackenzie, B. Moore, T. Pedersen, Y. Rosenthal, S. Seitzinger, V. Smetacek, and W. Steffen, The global carbon cycle: A test of our knowledge of earth as a system, Science, 290, 291–296, 2000.

Flynn, G. J., L. P. Keller, M. Feser, S. Wirick, and C. Jacobsen, The origin of organic matter in the solar system: Evidence from the interplanetary dust particles, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 67, 4791–4806, 2003.

Groves, B., M. A. Dopita, R. S. Sutherland, L. J. Kewley, J. Fischera, C. Leitherer, B. Brandl, and W. Van Breugel, Modeling the pan-spectral energy distribution of starburst galaxies. Iv. The controlling parameters of the starburst sed, Astrophys. J. Suppl., 176, 438–456, 2008.

Guillois, O., I. Nenner, R. Papoular, and C. Reynaud, Coal models for the infrared emission spectra of proto-planetary nebulae, Astrophys. J., 464, 810, 1996.

Hrivnak, B. J., K. Volk, and S. Kwok, 2–45 micron infrared spectroscopy of carbon-rich proto-planetary nebulae, Astrophys. J., 535,275–292,2000.

Jäger, C., F. J. Molster, J. Dorschner, T. Henning, H. Mutschke, and L. Waters, Steps toward interstellar silicate mineralogy—IV The crystalline revolution, Astron. Astrophys., 339, 904–916, 1998.

Kerridge, J. F., Formation and processing of organics in the early solar system, Space Sci. Rev., 90, 275–288, 1999.

Kwok, S., The synthesis of organic and inorganic compounds in evolved stars, Nature, 430, 985–991, 2004.

Kwok, S., Physics and Chemistry of the Interstellar Medium, University Science Books, Sausalito, 2007.

Kwok, S., Delivery of complex organic compounds from planetary nebulae to the solar system, Int. J. Astrobiol., 8, 161–167, 2009.

Kwok, S., K. Volk, and W. P. Bidelman, Classification and identification of IRAS sources with low-resolution spectra, Astrophys. J. Suppl., 112, 557, 1997.

Kwok, S., K. Volk, and P. Bernath, On the origin of infrared plateau features in proto-planetary nebulae, Astrophys. J., 554, L87–L90, 2001.

Leipski, C., K. Meisenheimer, U. Klaas, F. Walter, M. Nielbock, O. Krause, H. Dannerbauer, F. Bertoldi, M.-A. Besel, G. De Rosa, X. Fan, M. Haas, D. Hutsemekers, C. Jean, D. Lemke, H.-W. Rix, and M. Stickel, Herschel-PACS far-infrared photometry of two z>4 quasars, Astron. Astrophys., 518, L34, 2010.

Lorenz, R. D., K. L. Mitchell, R. L. Kirk, A. G. Hayes, O. Aharonson, H. A. Zebker, P. Paillou, J. Radebaugh, J. I. Lunine, M. A. Janssen, S. D. Wall, R. M. Lopes, B. Stiles, S. Ostro, G. Mitri, and E. R. Stofan, Titan's inventory of organic surface materials, Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, 02206, 2008.

Lynch, D. K. et al., Nova V2362 Cygni (Nova Cygni 2006): Spitzer,SWIFT, and ground-based spectral evolution, Astron. J., 136, 1815– 1827, 2008.

Matthews, C. N. and R. D. Minard, Hydrogen cyanide polymers, comets and the origin of life, Faraday Discuss., 133, 393–401, 2006.

Messenger, S., Identification of molecular-cloud material in interplanetary dust particles, Nature, 404, 968–971, 2000.

Nakamura-Messenger, K., S. Messenger, L. P. Keller, S. J. Clemett, and M. E. Zolensky, Organic globules in the Tagish Lake meteorite: Remnants of the protosolar disk, Science, 314, 1439–1442, 2006.

Nguyen, M.-J., F. Raulin, P. Coll, S. Derenne, C. Szopa, G. Cernogora, G. Isral, and J.-M. Bernard, Carbon isotopic enrichment in titan's tholins? Implications for titan's aerosols, Planet. Space Sci., 55, 2010–2014, 2007.

Öpik, E., On the physical interpretation of color-excess in early type stars, Harvard College Observatory Circular, 359, 1–17, 1931.

Papoular, R., The use of kerogen data in understanding the properties and evolution of interstellar carbonaceous dust, Astron. Astrophys., 378, 597–607, 2001.

Papoular, R., J. Conard, O. Guillois, I. Nenner, C. Reynaud, and J.-N. Rouzaud, A comparison of solid-state carbonaceous models of cosmic dust, Astron. Astrophys., 315, 222–236, 1996.

Sagan, C. and B. N. Khare, Tholins: Organic chemistry of interstellar grains and gas, Nature, 277, 102–107, 1979.

Sandford, S. A. et al., Organics captured from comet 81p/Wild 2 by the stardust spacecraft, Science, 314, 1720–1724, 2006.

Sarre, P. J., The diffuse interstellar bands: A major problem in astronomical spectroscopy, J. Mol. Spectrosc, 238, 1–10, 2006.

Smith, T. L. and A. N. Witt, The photophysics of the carrier of extended red emission, Astrophys. J., 565, 304–318, 2002.

Snow, T. P. and B. J. McCall, Diffuse atomic and molecular clouds, Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys., 44, 367–414, 2006.

Zinner, E., Stellar nucleosynthesis and the isotopic composition of presolar grains from primitive meteorites, Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci., 26,147– 188, 1998.

Ziurys, L. M., The chemistry in circumstellar envelopes of evolved stars: Following the origin of the elements to the origin of life, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 103, 12274–12279, 2006.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the SOC of the session on “Cosmic Dust: Its Formation and Evolution” in the 7th Annual Meeting of the Asia Oceania Geosciences Society in Hyderabad for its invitation to speak in the session. This work was supported by a grant to SK from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. HKU 7020/08P).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwok, S. Amorphous organic solids as a component of interstellar dust. Earth Planet Sp 63, 1021–1026 (2011). https://doi.org/10.5047/eps.2011.11.013

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5047/eps.2011.11.013