Abstract

Accurate reports of mediation analyses are critical to the assessment of inferences related to causality, since these inferences are consequential for both the evaluation of previous research (e.g., meta-analyses) and the progression of future research. However, upon reexamination, approximately 15 % of published articles in psychology contain at least one incorrect statistical conclusion (Bakker & Wicherts, Behavior Research Methods, 43, 666–678 2011), disparities that beget the question of inaccuracy in mediation reports. To quantify this question of inaccuracy, articles reporting standard use of single-mediator models in three high-impact journals in personality and social psychology during 2011 were examined. More than 24 % of the 156 models coded failed an equivalence test (i.e., ab = c – c′), suggesting that one or more regression coefficients in mediation analyses are frequently misreported. The authors cite common sources of errors, provide recommendations for enhanced accuracy in reports of single-mediator models, and discuss implications for alternative methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

The mediation model continues to be one of the most prevalent statistical approaches in the areas of personality and social psychology (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007; Rucker, Preacher, Tormala, & Petty, 2011; Smith, 2012). The prevalence of mediation analysis is fueled by an emphasis on detecting the psychological processes through which independent variables affect dependent variables. For example, dual-process models of impression formation and stereotyping (e.g., Bodenhausen, Macrae, & Sherman, 1999; Fiske, Lin, & Neuberg, 1999) often distinguish between cognitive and affective mechanisms and examine the potency of such constructs as mediators of the relationship between variables such as stereotype activation and discrimination (e.g., Dovidio et al., 2004).

Consequently, accurate statistical reports in general are critical to the validity of research conclusions, the evaluation of previous research (e.g., meta-analyses), and the progression of future research. Accurate statistical reports in mediation analyses are additionally critical given their ubiquity and the emphasis placed on such analyses in supporting inferences of causality.

A test of equivalency

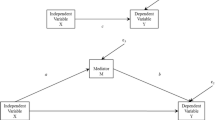

Although a variety of approaches offer the opportunity to provide evidence for causal inferences (see Hayes, 2009), researchers consistently rely on a single approach—namely, a set of analyses recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986). The Baron and Kenny method suggests that researchers estimate three regression equations to infer causality in single-mediator models (see Fig. 1): (1) regression of the mediator variable (M) on the independent variable (X; path a); (2) regression of the dependent variable (Y) on the independent variable (X; path c); and (3) simultaneous regression of the dependent variable (Y) on both the independent variable (X; path c′) and the mediator variable (M; path b). Importantly, complete mediation is argued to occur when paths a, b, and c are statistically significant and the reevaluation of path c with the mediator included in the model (i.e., c′) is reduced to nonsignificance.

Researchers are usually interested in the drop of the effect of the independent variable when the mediator is in the model (i.e., c – c′), as well as the test of the indirect effect (i.e., ab). Conveniently, in single-mediator models, ab = c – c′ for both standardized and unstandardized coefficients (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, 1998; MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993).Footnote 1 This test of equivalency, then, provides researchers with a simple and convenient check of the accuracy of single-mediator reports.

Sources of error

Errors in the accuracy of statistical reports have been well-documented. For instance, upon reexamination, approximately 15 % of published articles in psychology contain at least one incorrect statistical conclusion (Bakker & Wicherts, 2011; Berle & Starcevic, 2007; Wicherts, Bakker, & Molenaar, 2011). Yet to our knowledge, no research has studied the accuracy of mediation reports, an empirical absence of even more intrigue to social scientists when one considers the multitude of reasons that published reports of basic mediation analyses may be in error.

A discrepancy between ab and c – c′ (i.e., failed equivalence test) may occur for at least eight reasons: (1) using inconsistent rules to round coefficients; (2) reporting a mix of unstandardized and standardized coefficients; (3) failure to report missing data;Footnote 2 (4) failure to report the statistical control of other variables (i.e., covariates) in some models but not others; (5) failure to report the use of multiple mediators; (6) misreporting incorrect positive or negative signs of coefficients; (7) misreporting the b path coefficient using the single-predictor model whereby the dependent variable is regressed only onto the mediator (evidenced by incorrect degrees of freedom); and (8) failing to appropriately assign regression coefficients (e.g., confusing c for c′). More generally, inconsistencies may result from a typographical error, misreading the output of a statistical software program, application of incorrect rules, or a lack of knowledge. Beyond these common errors, researchers may inadvertently omit path coefficients from their reports. Given the nature of these errors and the inability to correct for (most of) them, the present investigation focused solely on analyses that clearly report coefficient values for all four necessary paths.

Of course, other sources of error may emerge, but these examples illustrate the opportunity for error in mediation and, consequently, the need to quantify the accuracy of such reports. When the equivalence test is failed, authors who present a flawed analysis have failed to make a valid case for either the presence or absence of a relationship, and any conclusion concerning whether or not the proposed mediator is a mechanism by which the independent variable affects the dependent variable may be inaccurate. Thus, a failed equivalence test error (e.g., a .03 difference between ab and c – c′) is not trivial; the discrepancy is signaling an error, and researchers may be either overstating a meditational mechanism or failing to detect one. Whether that error stems from the mediation model itself or inaccurate/insufficient reporting of the analysis, the adverse implications for the research findings—findings that are often in direct reference to causality—are the same.

Overview

The purpose of the present investigation is to offer insight into the prevalence and potential severity of inaccuracies in mediation analysis. We use as our criterion the discrepancy between ab and c – c′ in single-mediator models, given the widespread reliance on such models and the simplicity of the equivalency test. Moreover, we have no reason to suspect that misreports of mediation analyses are unique to particular research areas. Thus, we intentionally focused our content analysis on three high-impact journals within the domain of personality and social psychology, given the widespread use of the Baron and Kenny (1986) method to test mediation within these outlets (MacKinnon et al., 2007; Rucker et al., 2011; Smith, 2012). Finally, our hope is that this content analysis—by providing empirical evidence of the frequency and severity of inaccurate statistical reporting in mediation models—will offer greater insight into the means by which mediation reports can be more accurate.

Method

Procedure

As was noted, our goal was to quantify the current prevalence of mediation (in)accuracies. We therefore sought to identify journals within a domain where the use of the Baron and Kenny (1986) approach to mediation is widespread—personality and social psychology (see MacKinnon et al., 2007). Additionally, given our interest in understanding existing rates of discrepancy, we restricted our survey to journals within the calendar year of 2011. Consequently, we restricted our analysis to the flagship empirical journals of personality and social psychology published in 2011: Journal of Experimental Social Psychology (JESP), Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (JPSP), and Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin (PSPB).

From our survey of the journal issues, we identified 87 articles (34, 28, and 25 in JESP, JPSP, and PSPB, respectively) with at least one mediation analysis that met the following criteria: (1) reported regression coefficients either all standardized or all unstandardized; (2) clear assignment of the four path coefficients;Footnote 3 (3) no reported accounts of unequal missing data for any of the variables; (4) no other variables reported in the analysis beyond the independent, single-mediator, and dependent variables; and (5) employment of single-level linear and multiple regressions. An additional 30 articles were not coded due to incomplete reports (e.g., lacking one or more path coefficients), lack of clarity in path assignments, or simply containing too many inconsistencies to make a definitive assessment. Thus, we were quite conservative in determining the eligibility of models from our initial survey, making sure to examine only standard, single-mediator models.

Because some articles contained more than one analysis, this procedure yielded 156 mediation models for our analyses. For each model, we recorded the coefficients and calculated ab and c – c′. We then determined the magnitude of the discrepancy between ab and c – c′ for each model by calculating the absolute value of their difference, |ab – (c – c′)| (see the Table 1).

Criterion of error

The rounding of coefficients is likely to be a common source of small ab and c – c′ discrepancies. For instance, some ab and c – c′ discrepancies could be due to rounding up coefficients to the nearest one-hundredth (e.g., rounding up .345 to .35) and not others (e.g., .344). However, we note that even when a large indirect path (i.e., ab) is rounded up, rounding does not result in much difference from c – c′. For instance, if an a path of .635 were rounded to .64 and a b path of .755 were rounded to .76, the product would increase only by .007 (from .479 to .486). In fact, even if two coefficients of .98 were both rounded up to .99, the product would increase by .02 (from .96 to .98). Of course, as the coefficients become smaller, the influence of rounding becomes less probable as an explanation for an ab and c – c′ discrepancy. Thus, we find it difficult not to attribute an ab and c – c′ discrepancy greater than .02 to something other than rounding.Footnote 4

This difficulty aside, we elected to use a conservative criterion, one that removed any influence of inconsistencies in rounding of path coefficients. Specifically, for each reported model, we calculated a rounding interval for the product of ab and difference of c and c′. Intervals were calculated by first adding and subtracting .01 (and .001 when three decimals were reported) to each of the four reported path coefficients. After we calculated all four combinations of ab and all four combinations of c – c′, we found the smallest and greatest values of the products and differences to represent the possible intervals. When we found no overlap between the ab and c – c′ rounding intervals, we deemed the report as containing at least one error.

Results

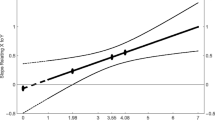

Of the 156 single-mediator models coded from 87 separate articles, the overall absolute discrepancy in the mean equivalence test value was .04 (SD = .09), 95 % CI: [.02, .05]. Figure 2 displays a histogram of the equivalence test results. Additionally, when we restricted our definition of an error to an absence of overlap in the ab and c – c′ rounding intervals, a total of 38 models (24.36 %) were defined as having at least one error. These models reached an equivalence test mean of .14 (SD = .14), 95 % CI: [.09, .18]. A total of 27 out of the 87 articles (31.03 %) included at least one model with an apparent error (20 articles included one model in error, 5 articles included two models in error, and 2 articles included four models in error). Importantly, analyses within articles were based on independent data (i.e., separate studies/samples).

Finally, to offer insight into the primary source of error, we examined |ab| and |c – c′| for each of the 38 mediation models in which there was an apparent error. Among these models, 25 (65.79 %) of the models reported |c – c′| greater than |ab|. This finding suggests that these equivalency errors stem from either an inflated |c – c′| or an understated |ab|. As is displayed in Fig. 3, the distance of a point from the equivalence diagonal indicates the magnitude of the |c – c′| – |ab| difference. When |ab| was greater than |c – c′|, the error points tended to fall relatively close to the equivalence diagonal, but when |c – c′| was greater than |ab|, the error points tended to fall relatively further from the equivalence diagonal.

Discussion

Our intent was to offer an empirical test of the accuracy of statistical reporting in mediation analyses, given their prevalence in personality and social psychology (MacKinnon et al., 2007) and the significance of mediation results for inferences of causality. We provided a tempered content analysis by focusing on a straightforward equivalency test for the most basic mediation analysis presented in three high-impact journals in personality and social psychology, using highly conservative criteria. Yet in spite of these conservative restrictions, our analysis suggests a significant problem in the reporting of mediation analyses. Indeed, we observed a robust discrepancy evidenced most clearly by the frequency by which the |ab| and |c – c′| discrepancy differed from zero and the fact that the |c – c′| calculation was frequently greater than the |ab| calculation in models that failed the equivalence test. Obviously, we believe these inaccuracies call into question the legitimacy of any findings where such discrepancy exists.

Implications

As has been noted, we believe these inaccuracies may result from a host of reasons independent of the analysis itself (e.g., failed or misreported statistics). Similar to Simmons, Nelson, and Simonsohn (2011), then, we do not suggest that such errors are the by-product of malicious intent. However, given the robustness of the discrepancies in our analysis, coupled with an absence of insight into the potential source of error when such models are published (as in the 156 models in our content analysis), it is difficult to ask readers to refrain from discrediting the legitimacy of the analysis, as well as any inferences that stem from the analysis.

Among the mediation criteria detailed by Baron and Kenny (1986), the drop in significance from c to c′ is often the most difficult criterion to meet; this criterion requires the researcher to identify a variable that not only significantly predicts the dependent variable, but also predicts enough unique variance to suppress the formerly significant variance of the initial predictor. Thus, one of our most concerning findings was that errors were driven by a potentially inflated c – c′ statistic. Again, we believe that this discrepancy may be driven by errors in statistical reporting and, thus, believe that the best solution to increased accuracy is (1) ensuring that the proper statistics are reported and (2) verifying these statistics by conducting an equivalence test that at least reveals some overlap between the ab and c – c′ intervals. On the other hand, our response is not blind to the possibility that a researcher’s desire to find statistical significance can implicitly augment the likelihood of committing such errors (see Dawson, Gilovich, & Regan, 2002; Edwards & Smith, 1996; Koehler, 1993; Rosenthal, 1978; Rossi, 1987).

Our survey focused on high-impact journals in personality and social psychology because, as was stated, the employment of mediation analyses is highly prevalent in this domain (MacKinnon et al., 2007). However, there is no reason to conclude that other subfields of psychology are immune to the problems we have highlighted here. Indeed, we have no reason to suspect that the prevalence of the ab and c – c′ discrepancy is different in other subfields of psychology (e.g., clinical, health, developmental, cognitive psychology). We also have no reason to suspect that the error rate would decrease for previous years or for journals of lesser impact.

Recommendations

Baron and Kenny’s (1986) recommendations have clearly served as a useful guide to mediation analysis. However, we believe that accuracy and clarity in the reporting of mediation analyses can be improved by either implementing several changes to reports of the traditional Baron and Kenny approach or adopting an alternative approach to mediation that relies more on the strength of the indirect effect (i.e., ab), rather than the weakness of the initial effect (i.e., c).

When the traditional Baron and Kenny’s (1986) approach is used, we strongly urge researchers to report all regression coefficients, making certain to uniformly report standardized or unstandardized coefficients. As was noted, we found several reports in which this information was simply incomplete (especially when mediation was reported absent any figure). Researchers should also provide the degrees of freedom for their tests of the various path coefficients. This will enable readers to detect whether or not the regression models were conducted properly (e.g., the tests of the b and c′ paths should have one less degree of freedom than the tests of the a and c paths) and determine whether or not coefficients have been properly assigned to their respective paths. Finally, of course, we recommend the employment of the convenient equivalence test. Researchers will be better positioned to detect their errors when the ab – (c – c′) equivalence test is failed (i.e., when it is not equal to zero).

Of course, the Baron and Kenny (1986) approach is not the only means by which causal inferences can be supported; researchers have made strong cases for the employment of moderation designs (e.g., Spencer, Zanna, & Fong, 2005) and other alternative methods of testing mediation (Hayes, 2009; MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000; MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; Rucker et al., 2011; Shrout & Bolger, 2002; Zhao, Lynch, & Chen, 2010). Within this tradition, we believe that there is a new approach to mediation analysis that may greatly reduce the frequency of the errors that we have highlighted here. As was noted, this new approach places greater emphasis on the indirect effect (ab) rather than on the initial effect (c) and, consequently, any potential c – c′ discrepancy. For instance, a particularly useful software application—PROCESS (Hayes, 2012)—permits researchers to test over 70 unique mediation models, including mediated moderation and moderated mediation. PROCESS employs a bootstrapping procedure and estimates indirect effects by calculating 95 % confidence intervals for each indirect effect, with mediation models deemed significant when the indirect effect confidence intervals do not include zero (see Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Thus, the utilization of PROCESS benefits researchers, reviewers, and readers alike by providing a simpler rule for signaling significant mediation. Importantly, PROCESS is accompanied by a user’s manual, as well as an organized and straightforward output. Furthermore, PROCESS employs error messages when specific models are configured incorrectly. We believe that these features will aid researchers in conducting accurate mediation analyses and will reduce the likelihood of error.

This alternative approach aside, we still contend that reporting each of the four coefficients in a single-mediator model remains the critical component to the evaluation of any mediation analysis. Indeed, the reporting of these paths will be useful to meta-analyses that may require knowledge about the relationships between variables that are not central to the causal hypothesis (relationships which the bootstrapping/CI approach does not require to be reported). Moreover, regardless of the approach, we recommend that researchers always report the necessary information to enable replication of mediation analyses.

Conclusion

Given the prevalence of mediation analyses, the emphasis placed on these analyses in inferring causality, and the implications of these inferences for both the evaluation of previous research and the progression of future research, it is critical that statistical reports of such analyses be accurate. Although our findings suggest considerable error in the current means by which mediation is reported, we believe that our suggested amendments to the current practices of reporting mediation using the Baron and Kenny (1986) method can dramatically reduce such error. Furthermore, we are encouraged by new advances in mediation analysis, although our hope is that the present findings emphasize the need for greater accuracy in the reporting of mediation analysis—regardless of the analytic tool employed.

Notes

It is important to note that this equivalence test holds for ordinary least squares regression but does not hold for other models, such as logistic regression (i.e., models whereby the criterion variable is dichotomous).

It is important to note that a failed equivalence test due to missing data would occur only when pairwise deletion of cases is employed. When there are missing data and listwise deletion is used (i.e., all cases missing on X, M, or Y are dropped), a failed equivalence test would not be due to missing data. However, when there are missing data and pairwise deletion is used (i.e., cases missing on M can still be used to estimate path c, and cases missing on Y can still be used to estimate path a), then the coefficients are being estimated using different subsets of data, which can result in a failed equivalence test.

Researchers often report the independent relationship between the proposed mediator and the dependent variable. In some cases, the coefficient belonging to the mediator from a simultaneous regression of the dependent variable on both the independent variable and the mediator is not reported (or it is unclear whether the coefficient was reported from a single-predictor regression or a multiple regression). Cases whereby this distinction was unclear were not included in our analyses.

It is worth noting that a misreport of one coefficient is enough to offset ab from c – c′; in such cases, readers are unable to determine, from the report alone, the particular coefficient(s) in error.

References

Bakker, M., & Wicherts, J. M. (2011). The (mis)reporting of statistical results in psychology journals. Behavior Research Methods, 43, 666–678.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Berle, D., & Starcevic, V. (2007). Inconsistencies between reported test statistics and p-values in two psychiatry journals. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 16, 202–207.

Bodenhausen, G. V., Macrae, C. N., & Sherman, J. W. (1999). On the dialectics of discrimination: Dual processes in social stereotyping. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual process theories in social psychology (pp. 271–290). New York: Guilford Press.

Dawson, E., Gilovich, T., & Regan, D. T. (2002). Motivated reasoning and performance on the Wason Selection Task. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1379–1387.

Dovidio, J.F., ten Vergert, M., Stewart, T.L., Gaertner, S.L., Johnson, J.D., Esses, V.M., …& Pearson, A.R. (2004). Perspective and prejudice: Antecedents and mediating mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1537–1549.

Edwards, K., & Smith, E. E. (1996). A disconfirmation bias in the evaluation of arguments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 5–23.

Fiske, S. T., Lin, M., & Neuberg, S. L. (1999). The continuum model: Ten years later. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual process theories in social psychology (pp. 231–254). New York: Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millenium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420.

Hayes, A.F. (2012). PROCESS. [Computer software] Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/spss-sas-and-mplus-macros-and-code.html

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Bolger, N. (1998). Data analysis in social psychology. In D. Gilbert, S. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology Vol. 1 (4th ed., pp. 233–265). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Koehler, J. J. (1993). The influence of prior beliefs on scientific judgments of evidence quality. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 56, 28–55.

MacKinnon, D. P., & Dwyer, J. H. (1993). Estimation of mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review, 17, 144–158.

MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593–614.

MacKinnon, D. P., Krull, J. L., & Lockwood, C. M. (2000). Equivalence of the mediation, confounding, and suppression effect. Prevention Science, 1, 173–181.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7, 83–104.

Rosenthal, R. (1978). How often are our numbers wrong? American Psychologist, 33, 1005–1008.

Rossi, J. S. (1987). How often are our statistics wrong? A statistics class exercise. Teaching of Psychology, 14, 98–101.

Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5, 359–371.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445.

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2011). False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychological Science, 22, 1359–1366.

Smith, E. R. (2012). Editorial. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 1–3.

Spencer, S. J., Zanna, M. P., & Fong, G. T. (2005). Establishing a causal chain: Why experiments are often more effective than mediational analyses in examining psychological processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 845–851.

Wicherts, J. M., Bakker, M., & Molenaar, D. (2011). Willingness to share research data is related to the strength of the evidence and the quality of reporting of statistical results. Public Library of Science ONE, 6, 1–7.

Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 197–206.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Petrocelli, J.V., Clarkson, J.J., Whitmire, M.B. et al. When ab ≠ c – c′: Published errors in the reports of single-mediator models. Behav Res 45, 595–601 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-012-0262-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-012-0262-5