Abstract

After attention has been involuntarily captured by a distractor, how is it reoriented toward a target? One possibility is that attention to the distractor passively fades over time, allowing the target to become attended. Another possibility is that the captured location is actively suppressed so that attention can be directed toward the target location. The present study investigated this issue with event-related potentials (ERPs), focusing on the N2pc component (a neural measure of attentional deployment) and the Pd component (a neural measure of attentional suppression). Observers identified a color-defined target in a search array, which was preceded by a task-irrelevant cue array. When the cue array contained an item that matched the target color, this item captured attention (as measured both behaviorally and with the N2pc component). This capture of attention was followed by active suppression (indexed by the Pd component), and this was then followed by a reorienting of attention toward the target in the search array (indexed by the N2pc component). These findings indicate that the involuntary capture of attention by a distractor is followed by an active suppression process that presumably facilitates the subsequent voluntary orienting of attention to the target.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Attention can be voluntarily deployed toward relevant information or involuntarily captured by an irrelevant item. Much is known about the mechanisms by which attention is voluntarily or involuntarily allocated, but little is known about how the brain recovers after being involuntarily captured by an irrelevant item so that attention can be reoriented to relevant information. One possibility is that attention passively fades after being involuntarily captured by a distractor. Another possibility is that an active suppression process is applied to disengage attention from the distractor, especially if attention is needed for a concurrent or upcoming target.

The present study assesses the processes that occur during the transition from attentional capture by a distractor to attentional reorienting toward a target. This issue is difficult to study behaviorally because it involves the processes that intervene between the orienting of attention to one stimulus and the reorienting of attention to another stimulus, and we therefore recorded event-related potentials (ERPs) to provide a continuous measure of attention over this time period. We focused on the N2pc and Pd components. The N2pc component is a well-characterized index of the covert deployment of visual attention (Luck & Hillyard, 1994a, 1994b; for a review, see Luck, 2012). This component is observed at lateral occipital-temporal scalp sites as a more negative voltage at scalp sites contralateral to an attended item, relative to ipsilateral scalp sites, and it typically begins 150–225 ms after stimulus onset. In contrast, the Pd component appears to reflect active attentional suppression (Hickey, Di Lollo, & McDonald, 2009; Kiss, Grubert, Petersen, & Eimer, 2012; Sawaki, Geng, & Luck, 2012; Sawaki & Luck, 2010, 2011). This component is observed at lateral occipital-temporal scalp sites as a more positive voltage at contralateral scalp sites relative to ipsilateral scalp sites, relative to the position of a to-be-suppressed item in a display. It begins 100–400 ms after stimulus onset, depending on the stimuli and task. Using these components, previous studies have investigated the mechanisms by which attention is captured by distractors (indexed by N2pc) and the mechanisms by which the actual capture of attention is prevented by active suppression control in some situations (indexed by Pd). The present study asks a previously unexplored question: How does the brain recover from the involuntarily capture of attention once it has occurred?

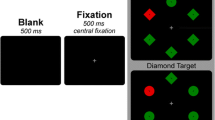

The present study used a cuing capture paradigm in which a cue array containing task-irrelevant circles was presented prior to a search array containing a search target (see Fig. 1). One of the circles in the cue array could have the same color as the search target, leading to attention capture by this target-color cue. If attention simply fades away passively after being captured by the target-color cue, followed by orienting of attention to the target, an N2pc component should be observed for the target-color cue, and then another N2pc component should be observed for the search target. If, however, an active suppression process is applied after attention is captured by the target-color cue, a Pd component should be observed after the N2pc to the target-color cue and before the N2pc to the search target.

Example stimulus displays. The cue array consisted of four colored circles on 80 % of trials and four gray circles on 20 % of trials. Observers searched for an object of a predefined target color in the search array and reported whether this object contained a top gap or a bottom gap. They were told to ignore the cue array. When the cue array contained four colors, one matched the color of the subsequent target, but the location of this target-color cue was nonpredictive of the location of the target

Method

Participants

The participants were 12 neurologically normal volunteers (8 female, 4 male) between 18 and 30 years old who were paid for their participation. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and provided informed consent.

Stimuli and procedure

The stimuli were presented on a video monitor with a black background (luminance: 0.39 cd/m2) and a continuously visible gray fixation cross (0.3° × 0.3°) at a distance of 70 cm (see Fig. 1). At the beginning of each block of trials, one member of a set of four colors (red, u′ = .46, v′ = . 50; green, u′ = .14, v′ = .55; blue, u′ = .19, v′ = .23; yellow, u′ = .26, v′ = .53) was designated as the target color. The red-target, green-target, blue-target, and yellow-target blocks occurred in random order.

Each trial began with a blank intertrial interval (1,500–1,700 ms, rectangular distribution), followed by a 100-ms cue array. Each cue array consisted of four filled circles (1.6° × 1.6°, centered 2.5° above or below the horizontal meridian and 2.5° to the left or right of the vertical meridian). On 80 % of the trials, the color of each circle was selected randomly without replacement from the set of four colors (a color never repeated within a given display). On the remaining 20 % of the trials, all four circles were gray. The colored-circle and gray-circle trials occurred in random order. All stimuli were matched for luminance (18 cd/m2).

After a blank delay period (200 ms), a search array was presented for 100 ms (stimulus onset asynchrony [SOA] = 300 ms). It should be noted that prior experiments using this general approach have found capture effects with this 300-ms SOA (Lamy & Egeth, 2003), and no inhibition of return would be expected at this SOA because the cues were not purely exogenous (Henderickx, Maetens, & Soetens, 2012). Each search array consisted of four outlined squares (1.9° × 1.9°, centered 2.5° above or below the horizontal meridian and 2.5° to the left or right of the vertical meridian). Two squares had a gap (missing side) on the top, and the other two squares had a gap on the bottom; except for this constraint, the location of each gap was selected at random on every trial. The color of each square was selected randomly without replacement from the set of four colors. Participants were instructed to report the location of the target square’s gap (top or bottom) by pressing one of two spatially corresponding buttons on a game pad with the right-index and middle fingers as quickly and accurately as possible.

The combination of cues and targets led to five types of trials, each with equal probability (320 trials each): same-quadrant trials (target-color cue and target in the same quadrant), vertical-quadrant trials (target-color cue and target directly across the horizontal meridian), horizontal-quadrant trials (target-color cue and target directly across the vertical meridian), diagonal-quadrant trials (target-color cue and target in diagonally opposed positions), and neutral trials (cue circles were gray).

Each participant performed 80 practice trials, followed by 20 blocks of 80 trials during which ERPs were recorded. Participants were explicitly instructed that circles in the cue array were task irrelevant and did not predict a location of the target on the search array. They were required to maintain central fixation throughout each trial, verified with electrooculogram (EOG) recordings (see details below and online supplementary materials).

Recording and analysis

The electroencephalogram (EEG) and EOG were recorded at 1024 Hz with an antialiasing filter at 208 Hz (half-power cutoff) using our standard methods (Sawaki & Luck, 2010). The EEG signals were referenced offline to the average of the left and right mastoids, and bipolar vertical and horizontal EOG derivations were computed for the EOG signals. All signals were bandpass-filtered offline (Butterworth filter, half-power bandwidth of 0.1–30 Hz, roll-off of 12 dB/octave) and then down-sampled to 256 Hz. Averaged ERP waveforms were computed with an 800-ms epoch, beginning 100 ms before cue array onset. The waveforms were collapsed across stimulus colors and locations to eliminate sensory confounds related to these factors. Trials were automatically excluded if they contained an incorrect response or if the reaction time (RT) was shorter than 100 ms or longer than 1,100 ms (< 0.9 % of trials). A combination of artifact rejection and artifact correction (via independent component analysis) was used to eliminate eye blinks. Trials were also excluded if the postcorrection EEG exceeded ±100 μV in any channel, if the vertical or horizontal EOG exceeded ±80 μV, or if a step function applied to the horizontal EOG exceeded 15 μV (see Luck, 2005, p. 161). One participant was replaced because of excessive artifacts. For more details, see online supplementary materials.

N2pc and Pd amplitudes were measured as the difference between electrode sites contralateral and ipsilateral to either the target-color cue or the search target. Both components were measured at the PO7 and PO8 electrode sites, where they were largest in previous studies, as well as in the present study. Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and t-tests were used for statistical tests, and p-values were adjusted when appropriate with the Greenhouse–Geisser corrections to the degrees of freedom.

Results

Behavioral results

Mean RT and mean hit rate are shown for each trial type in Fig. 2. RT was shortest on same-quadrant trials, intermediate on neutral trials, and slowest on the vertical-, horizontal-, and diagonal-quadrant trials. The effect of trial type was significant in a one-way ANOVA, F(4, 44) = 36.3, p < .001, and follow-up t tests indicated that RT was significantly shorter for same-quadrant trials than for each of the other trial types (p ≤ .001 for all cases).

Behavioral results. Reaction time (a) and hit rate (b) for each trial type. Error bars represent 95 % within-subjects confidence intervals (Loftus & Masson, 1994)

A complementary but somewhat weaker pattern was observed for hit rate. The main effect of trial type was again significant, F(4, 44) = 4.7, p = .007, and follow-up t-tests indicated that hit rate was significantly higher for same-quadrant trials than for vertical-quadrant trials (p = .047) and horizontal-quadrant trials (p = .019). These RT and accuracy effects indicate that the target-color cue captured attention.

ERP results

Figure 3 shows the ERP waveforms from the same-quadrant, vertical-quadrant, and neutral trials. Separate waveforms are shown for contralateral and ipsilateral sites, relative to the visual hemifield of the target-color cue (and also relative to the target, which was in the same hemifield as the target-color cue on these trials). Contralateral-minus-ipsilateral difference waves are shown in Fig. 3d, making it easier to see the N2pc and Pd components.

Grand average ERPs, time-locked to the onset of the cue array for same-quadrant trials (a), vertical-quadrant trials (b), and neutral trials (c), averaged over the PO7 and PO8 electrode sites. Separate waveforms are shown for contralateral versus ipsilateral electrode hemispheres, relative to the side of the target-color cue (which was also contralateral to the side of the target on these trials). Grand average difference waveforms are also shown (d), obtained by subtracting the ipsilateral waveforms from the contralateral waveforms. The gray areas indicate the period of the cue array and the search array

On both the same-quadrant and vertical-quadrant trials, the N2pc component can be seen as a negative deflection in the contralateral-minus-ipsilateral difference waves, beginning approximately 150 ms after the onset of the cue array. A Pd component can also be seen as a positive deflection, beginning approximately 400 ms after the onset of the cue array (i.e., 100 ms after the onset of the search array). Following the Pd, another N2pc component was observed, beginning approximately 480 ms from the onset of the cue array (i.e., 180 ms from the onset of the search array).

For the neutral trials, only the target-elicited N2pc component was present, beginning at approximately 450 ms from the onset of the cue array (i.e., 150 ms after the onset of the search array). On horizontal-quadrant and diagonal-quadrant trials, the cue-elicited Pd and target-elicited N2pc were the same polarity and, therefore, could not be isolated from each other. Consequently, these data were ambiguous and are not presented here (but are presented in Fig. S1 in the online supplementary materials).

To assess the statistical significance of these effects, the voltage was measured from the contralateral-minus-ipsilateral difference waves for the cue N2pc (175–225 ms postcue), the cue Pd (400–450 ms postcue), and the target N2pc (200–300 ms posttarget) and was analyzed with one-sample t-tests and one-way ANOVAs. All statistical results were confirmed with nonparametric permutation tests that do not depend on precisely defined measurement windows (see the online supplementary materials).

One-sample t-tests indicated that the N2pc following the cue array was significantly greater than zero for both same-quadrant trials, t(11) = −3.2, p = .009, and vertical-quadrant trials, t(11) = −3.6, p = .004. The permutation test was also significant for both same-quadrant trials (p = .043) and vertical-quadrant trials (p = .004; Fig. S2-A). A one-way ANOVA indicated that the N2pc was not significantly different between these trial types, F(1, 11) = 0.2. Thus, the target-color cue elicited an N2pc, reflecting the allocation of attention to its location. Because there was no unique lateralized item on neutral trials, there was no way to assess the N2pc component on those trials.

The Pd component (400–450 ms postcue) was also significantly greater than zero for both same-quadrant trials, t(11) = 3.6, p = .004, and vertical-quadrant trials, t(11) = 4.4, p = .001, with no difference between them, F(1, 11) = 0.4. These effects were confirmed by the permutation tests [same-quadrant trials, p = .038; vertical-quadrant trials, p = .005; Fig. S2-B]. Because the Pd effect began approximately 90 ms after search array onset, it is very unlikely that it could have been a response to the target within the search array. Consistent with this, no significant Pd was observed contralateral to the target when it was preceded by a neutral cue, t(11) = −0.2. Moreover, the difference in Pd amplitude between neutral trials, same-quadrant trials, and vertical-quadrant trials was significant in a one-way ANOVA, F(2, 22) = 7.7, p = .006. In addition, a Pd was also observed contralateral to the target-color cue when the search target was in the opposite field (see Fig. S1 in the online supplementary materials). Thus, the Pd reflected suppression of the target-color cue location and was not a response to the target itself.

The N2pc following the search array was significantly greater than zero for same-quadrant trials, t(11) = −5.6, p < .001, vertical-quadrant trials, t(11) = −4.7, p = .001, and neutral trials, t(11) = −4.0, p = .002. Permutation tests were also significant (p < .001 for all cases; Fig. S2-C). Thus, attention was shifted back to the target location once the search display appeared. The N2pc was numerically larger on same- and vertical-quadrant trials than on neutral trials, but this effect did not reach significance in a one-way ANOVA, F(2, 22) = 3.3, p = .0558.

To assess the onset and peak latencies of the target N2pc for same- and vertical-quadrant trials, we used a jackknife-based procedure (Miller, Patterson, & Ulrich, 1998). N2pc onset was defined as the latency at which the N2pc (measured from the contralateral-minus-ipsilateral difference wave) reached 50 % of the peak amplitude of the waveform (Kiesel, Miller, Jolicoeur, & Brisson, 2008). N2pc onset latency was 493 ms for same-quadrant trials and 499 ms for vertical-quadrant trials. N2pc peak latency was 554 ms for same-quadrant trials and 591 ms for vertical-quadrant trials. The latency values were entered into in a t-test, with the t score corrected according to the formula provided by Ulrich and Miller (2001). This analysis indicated that latency difference between these conditions was marginally significant [onset latency, corrected t(11) = −1.4, p = .096; peak latency, corrected t(11) = −1.0, p = .176]. This trend of shorter N2pc latency in the same-quadrant trials is consistent with the behavioral finding (i.e., shorter RT in the same-quadrant trials). Note that N2pc latency for neutral trials cannot be directly compared with that for same- and vertical-quadrant trials, because the overlapping Pd for the same-quadrant and vertical-quadrant trials likely distorted the apparent N2pc onset and peak latencies (Luck, 2005).

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that, when attention is captured by an item that is task irrelevant but shares a target feature, attention can reorient fairly rapidly when a target is subsequently presented (Folk, Remington, & Johnston, 1992; Folk, Remington, & Wright, 1994; Lamy & Egeth, 2003; Lamy, Leber, & Egeth, 2004). The present behavioral findings are consistent with this. Specifically, the target in the search array was detected more rapidly when it was preceded by a target-color cue in the same quadrant (as compared with the neutral trials), indicating that the cue captured attention. However, target detection was slowed by only about 15 ms when the cue and target appeared in different quadrants (as compared with the neutral trials), indicating that attention could be reoriented rapidly after being captured by the target-color cue. The ERPs provide a continuous measure of processing in the period between the onset of the cue and the response to the target, making it possible to understand how this rapid reorienting occurred.

Specifically, the target-color cue led to an N2pc, reflecting the capture of attention by this item (Eimer & Kiss, 2008), but this N2pc was followed by a Pd, which appears to reflect a squashing of attentional priority (see especially Sawaki et al., 2012). Thus, the attentional priority at the location of the target-color cue had been reduced via the Pd mechanism by the time the search array was presented, making it possible to rapidly generate an N2pc to the target whether it appeared in the same quadrant as the preceding target-color cue (i.e., on a same-quadrant trial) or in a different quadrant (i.e., on a vertical-quadrant trial). The priority must not have completely returned to a neutral state, however, because a shorter RT and N2pc were observed when the target appeared in the same quadrant as the target-color cue rather than in a different quadrant. This may reflect an incomplete termination of attention or some parallel mechanism of attention that is not terminated in this manner.

These results do not appear to reflect a passive decay of attention after capture by the target-color distractor. If attention had passively decayed, the ERPs on trials with a target-color distractor should have been just like the ERPs on neutral trials once the N2pc ended. However, a large Pd was present beginning 400 ms after the onset of the cue array when this array contained a target-color distractor. Several previous studies have now established that this Pd effect reflects an active suppression mechanism that is under top-down control (Hickey et al., 2009; Kiss et al., 2012; Sawaki et al., 2012; Sawaki & Luck, 2010, 2011). The present study adds to this growing literature by showing that this active suppression mechanism is also involved in the transition from attentional capture by a distractor to attentional reorienting toward a target.

Although the Pd occurred slightly after the onset of the search array, the initial portion of the Pd was the same irrespective of the location of the search target (see Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, the process reflected by the Pd was presumably applied to the location of the target-color cue, not to the target. The onset latency of the Pd component varies over a broad range (ca. 100–400 ms), depending on the stimuli and task, and the observed Pd in the present study was relatively late within the range. Given that the Pd occurred very close to the onset time of the target array, which was the same on each trial, it is possible that the Pd was entrained to the anticipated onset time of the target array. Additional research is necessary to determine the factors that control the timing of this process.

It should be emphasized that target N2pc for neutral trials cannot be directly compared with those for same- and vertical-quadrant trials. Any differences in target N2pc could be a result of the overlapping Pd (Luck, 2005). For this reason, the pattern of target N2pc between neutral trials and same-/vertical-quadrant trials also cannot be directly compared with the pattern of RTs between these trials.

It should be noted that several studies have examined ERPs in similar contingent capture paradigms (Eimer & Kiss, 2008, 2010; Eimer, Kiss, Press, & Sauter, 2009; Leblanc, Prime, & Jolicoeur, 2008; Lien, Ruthruff, Goodin, & Remington, 2008), and some evidence of a Pd was observed in the postcue portion of the waveforms in all of them. However, the Pd was not fully investigated in these studies, because they were conducted before the Pd had been identified as a distinct ERP component and/or because an active suppression process was not the main interest in these studies. Consequently, the paradigms and analyses were not optimal for testing the Pd in these studies. Thus, the present finding appears to be quite general, and the present study provides new insights into the mechanisms by which the brain recovers from involuntary capture of attention.

References

Eimer, M., & Kiss, M. (2008). Involuntary attentional capture is determined by task set: Evidence from event-related brain potentials. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20, 1423–1433.

Eimer, M., & Kiss, M. (2010). Top-down search strategies determine attentional capture in visual search: Behavioral and electrophysiological evidence. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 72, 951–962.

Eimer, M., Kiss, M., Press, C., & Sauter, D. (2009). The roles of feature-specific task set and bottom-up salience in attentional capture: An ERP study. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 35, 1316–1328.

Folk, C. L., Remington, R. W., & Johnston, J. C. (1992). Involuntary covert orienting is contingent on attentional control settings. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 18, 1030–1044.

Folk, C. L., Remington, R. W., & Wright, J. H. (1994). The structure of attentional control: Contingent attentional capture by apparent motion, abrupt onset, and color. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 20, 317–329.

Henderickx, D., Maetens, K., & Soetens, E. (2012). The involvement of bottom-up saliency processing in endogenous inhibition of return. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 74, 285–299.

Hickey, C., Di Lollo, V., & McDonald, J. J. (2009). Electrophysiological Indices of Target and Distractor Processing in Visual Search. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 21, 760–775.

Kiesel, A., Miller, J., Jolicoeur, P., & Brisson, B. (2008). Measurement of ERP latency differences: A comparison of single-participant and jackknife-based scoring methods. Psychophysiology, 45, 250–274.

Kiss, M., Grubert, A., Petersen, A., & Eimer, M. (2012). Attentional capture by salient distractors during visual search is determined by temporal task demands. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24, 749–759.

Lamy, D., & Egeth, H. E. (2003). Attentional capture in singleton-detection and feature-search modes. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 29, 1003–1020.

Lamy, D., Leber, A., & Egeth, H. E. (2004). Effects of task relevance and stimulus-driven salience in feature-search mode. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 30, 1019–1031.

Leblanc, E., Prime, D. J., & Jolicoeur, P. (2008). Tracking the location of visuospatial attention in a contingent capture paradigm. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20, 657–671.

Lien, M., Ruthruff, E., Goodin, Z., & Remington, R. W. (2008). Contingent attentional capture by top-down control settings: Converging evidence from event-related potentials. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 34, 509–530.

Loftus, G. R., & Masson, M. E. J. (1994). Using confidence intervals in within-subject designs. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 1, 476–490.

Luck, S. J. (2005). An Introduction to the Event-Related Potential Technique. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Luck, S. J. (2012). Electrophysiological correlates of the focusing of attention within complex visual scenes: N2pc and related ERP components. In S. J. Luck & E. S. Kappenman (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of ERP Components. New York: Oxford University Press.

Luck, S. J., & Hillyard, S. A. (1994a). Electrophysiological correlates of feature analysis during visual search. Psychophysiology, 31, 291–308.

Luck, S. J., & Hillyard, S. A. (1994b). Spatial filtering during visual search: Evidence from human electrophysiology. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 20, 1000–1014.

Miller, J., Patterson, T., & Ulrich, R. (1998). Jackknife-based method for measuring LRP onset latency differences. Psychophysiology, 35, 99–115.

Sawaki, R., Geng, J. J., & Luck, S. J. (2012). A common neural mechanism for preventing and terminating the allocation of attention. Journal of Neuroscience, 32, 10725–10736.

Sawaki, R., & Luck, S. J. (2010). Capture versus suppression of attention by salient singletons: Electrophysiological evidence for an automatic attend-to-me signal. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 72, 1455–1470.

Sawaki, R., & Luck, S. J. (2011). Active suppression of distractors that match the contents of visual working memory. Visual Cognition, 19, 956–972.

Ulrich, R., & Miller, J. (2001). Using the jackknife-based scoring method for measuring LRP onset effects in factorial designs. Psychophysiology, 38, 816–827.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by Grant R01MH076226 to S.J.L. from the National Institute of Mental Health and by a postdoctoral fellowship to R.S. from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Risa Sawaki, University of California Davis, Center for Mind and Brain, 267 Cousteau Place, Davis, CA 95618, USA. E-mail: rsawaki@ucdavis.edu

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 186 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sawaki, R., Luck, S.J. Active suppression after involuntary capture of attention. Psychon Bull Rev 20, 296–301 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-012-0353-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-012-0353-4