Abstract

Previous studies, such as those by Kornell and Bjork (Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14:219–224, 2007) and Karpicke, Butler, and Roediger (Memory, 17:471–479, 2009), have surveyed college students’ use of various study strategies, including self-testing and rereading. These studies have documented that some students do use self-testing (but largely for monitoring memory) and rereading, but the researchers did not assess whether individual differences in strategy use were related to student achievement. Thus, we surveyed 324 undergraduates about their study habits as well as their college grade point average (GPA). Importantly, the survey included questions about self-testing, scheduling one’s study, and a checklist of strategies commonly used by students or recommended by cognitive research. Use of self-testing and rereading were both positively associated with GPA. Scheduling of study time was also an important factor: Low performers were more likely to engage in late-night studying than were high performers; massing (vs. spacing) of study was associated with the use of fewer study strategies overall; and all students—but especially low performers—were driven by impending deadlines. Thus, self-testing, rereading, and scheduling of study play important roles in real-world student achievement.

Similar content being viewed by others

When college students study for their classes, what strategies do they use? Some study strategies—such as rereading text materials and cramming for tests—are commonly endorsed by students (e.g., Karpicke, Butler, & Roediger, 2009; Taraban, Maki, & Rynearson, 1999), even though they may not always yield durable learning. Other strategies—like self-testing—have been demonstrated to be quite effective (Roediger & Butler, 2011), but are mentioned less frequently when students report their strategies (e.g., Karpicke et al., 2009). Of course, not all students report using the same strategies—individual differences exist between students with regard to their study habits. Are these individual differences in study habits related to student achievement? If so, what differences exist between the study habits of high achievers and low achievers? A main goal of the present study was to answer these two questions, focusing on when students schedule their study as well as which strategies they use to learn course content. Our target strategies included those that appear popular with students or that cognitive research has indicated could promote student performance, such as self-testing, asking questions, and rereading. We will first provide a brief review of studies that have investigated these specific strategies, followed by an overview of the present study and its contribution to understanding strategy use and student achievement.

Two large-scale studies have surveyed students about their regular use of specific, concrete study strategies and their rationale for using them. One survey was administered by Kornell and Bjork (2007), who sought to describe what students do to manage their real-world study. A group of 472 introductory psychology students at UCLA responded to forced choice questions regarding topics such as how they decide what to study next and whether they typically read class materials more than once. Kornell and Bjork’s questionnaire and the percentages of students endorsing various scheduling practices and strategies are presented in Table 1. Results relevant to our present aims included that the majority of students (59%) prioritize for study whatever is due soonest, and that the majority of students use quizzes to evaluate how well they have learned course content (68%).

Another survey focused more narrowly on a particular strategy—self-testing—that an abundance of research has shown can boost student learning (for a recent review, see Roediger & Butler, 2011). In particular, Karpicke et al. (2009) had 177 undergraduates free-report and then rank-order the strategies that they used when studying. These reports were followed by a forced choice question regarding their preferences for rereading versus self-testing. In the free reports, self-testing and other retrieval-type activities (e.g., using flashcards) were commonly reported, but the strategy most frequently reported (by 83.6% of students) was rereading notes or textbooks. For the forced choice question, rereading was again the most popular choice, and retrieval practice became similarly popular only when it was accompanied by the possibility of rereading (allowing for restudy after practice testing). Students’ explanations revealed that most students self-test for the feedback about what they do or do not know rather than as a means to enhance learning. These results were consistent with the general conclusions of Kornell and Bjork (2007), as well as with the recent conclusions of McCabe (2011), who found that students often fail to understand that certain activities—such as testing (vs. restudying) or spacing study (vs. massing study)—are likely to enhance learning.

Although these studies reported valuable information about the prevalence of self-testing and students’ rationale for its use, self-testing is just one of many strategies that students use. Thus, a goal of the present study was (a) to assess a wider range of commonly used study strategies (in addition to those surveyed by Kornell & Bjork, 2007), such as underlining while reading and making outlines or diagrams, as well as (b) to assess how students schedule their study, such as when they study during the day and whether they space or mass their practice.

Most important, the relationship between students’ reported use of these strategies and their overall grades was investigated. In the studies by Kornell and Bjork (2007) and Karpicke et al. (2009), some strategies were more popular than others, but not all students endorsed using the same ones. Neither study examined whether these individual differences in strategy use were related to student achievement. Of course, individual differences in the use of study strategies are interesting from the perspective of how students regulate their learning, but the use of these strategies will matter most if they are related to student achievement. Thus, when students are partitioned by grade point average (GPA), will different patterns of study strategies emerge?

Theories of self-regulated learning (SRL) claim that learners use a variety of strategies to achieve their learning goals, and that the quality of strategy use should be related to performance (e.g., Winne & Hadwin, 1998; for a general review, see Dunlosky & Metcalfe, 2009). Certainly, strategies such as self-testing improve performance in the laboratory and when administered in the classroom (McDaniel, Agarwal, Huelser, McDermott, & Roediger, 2011; McDaniel & Callender, 2008). Nevertheless, it is not evident whether this aspect of SRL theory largely pertains to more controlled settings (e.g., in the lab or when administered by a teacher) or is more broadly applicable to settings in which students are responsible for regulating their learning. Indeed, for several reasons, a relationship between strategy use and achievement level is not guaranteed. First, the effectiveness of laboratory-tested strategies may not be as robust when these strategies are applied in the real world of student achievement, in which numerous courses (spanning different contents and cognitive abilities) contribute to students’ GPA. In fact, in a popular survey of learning strategies (i.e., the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire), the question most relevant to self-testing (#55, “I ask myself questions to make sure I understand the material…”) was not statistically correlated with course grades (Pintrich, Smith, Garcia, & McKeachie, 1991). Moreover, the performance benefits of some strategies are often largest after longer retention intervals (e.g., Roediger & Karpicke, 2006), and hence their contributions to exam performance may be limited by many students’ propensity to cram the night before tests (Taraban et al., 1999). Second, even if recommended strategies are an effective means of improving GPA, it is possible that successful students achieve their success in spite of (1) using the same pattern of strategies as low performers or (2) using even poorer strategy options. In the former case, perhaps high and low performers choose the same strategies, but high performers use them more adeptly. In the latter case, perhaps other factors—such as intelligence, prior experience, or degree of motivation—overpower the differential use of study strategies in determining GPA.

Given that the relationship between strategy endorsement and GPA is uncertain, our primary goal was to estimate the relationship between strategy use and GPA, with a specific focus on students’ use of self-testing and how students schedule their study time. To do so, we administered an expanded version of Kornell and Bjork’s (2007) survey. Additional questions were essential for accomplishing our most critical aims (see Table 1): First, three questions (8–10) addressed how students scheduled their study time. The first two were relevant to when during the day students studied and what time they believed would be most effective. Afternoon and evening studying would better match college students’ peak diurnal rhythms (May, Hasher, & Stoltzfus, 1993), and hence might be related to GPA. Question 10 concerned whether students spaced or massed their studying, and given the literature on the superiority of spaced practice (over massed; Cepeda, Pashler, Vul, Wixted, & Rohrer, 2006), we expected a consistent relationship between GPA and spacing (vs. massing) study. Second, a checklist of popular study strategies (Question 12) was included, because the original survey by Kornell and Bjork largely concerned why students used a particular strategy (e.g., self-testing), so the addition of this checklist was vital for estimating the relationship between strategy use and GPA.

Method

Participants

A group of 324 participants (72% female, 28% male) were recruited from the KSU participant pool, which mainly consists of students enrolled in introductory psychology courses. Introductory psychology enrollment included 78% freshmen, 15% sophomores, 4% juniors, and 2% seniors during the semesters the survey was administered. Given that introductory psychology is a popular course that is required by many programs across KSU, this pool includes a diverse population of students cutting across colleges and majors. Students received credit in their courses for participation.

Procedure

The survey described above (see Table 1) was administered to these 324 students. They were instructed to fill out the survey, which typically took less than 10 min to complete.

Even though GPA was self-reported (Question 11, Table 1), it was expected to be highly related to actual GPA, with any systematic inaccuracy working against the hypothesis that strategy use would be related to GPA. Namely, Bahrick, Hall, and Dunlosky (1993) investigated the accuracy of self-reported and actual grades, and they found that students with higher GPAs made accurate reports, whereas the largest discrepancies occurred for the poorest-performing students, who typically overestimated performance. Any overestimates of GPA from the poorer students in the present study would attenuate strategy–GPA relationships, and hence would work against the expectations from SRL theory.

Results

Our focal analyses involved comparing GPA to strategy use (and most notably, the use of self-testing strategies). However, below we first report the overall responses to the strategy questionnaire (a) to evaluate whether our survey results replicated those of Kornell and Bjork (2007), (b) to discuss our new results concerning how students schedule their study (Questions 8–10, Table 1), and (c) to highlight possible individual differences in strategy use (Question 12).

Response proportions

The first seven questions were identical to those used by Kornell and Bjork (2007), and Table 1 shows a side-by-side comparison of the response percentages at UCLA and those of the present study. Most striking is the similarity between the two sets of responses. The median difference between the responses is only 6 percentage points, and the rank orders of the percentages of responses are nearly identical across the two sites. Highlights include that most students reported using self-testing (Question 6) as a metacognitive tool to evaluate their progress and not as a means to boost performance, although self-testing can serve this dual purpose. Also, most students reported scheduling practice by focusing on whatever was due the soonest (Question 2), although individual differences in scheduling did arise, with some students (13%) developing plans on how to schedule time. Two apparent differences between the sites are that more students in the present study endorsed that they use self-testing because they learn more (Question 6), and more claimed that a teacher taught them how to study (Question 1). Given the few differences across sites, however, we caution against any interpretation of these apparent differences and instead emphasize the consistency in student responding.

Results from the new questions (8–10) provided further information about how students schedule study. Concerning time-of-day schedules, most students reported studying in the evening (and 20% report studying late at night), and fewer than 15% reported studying during the afternoon or earlier, even though 42% of the students indicated that studying was most effective in the afternoon or morning. More important, students were about evenly split (Question 10) with respect to whether they reported spacing or massing their studying. Those who reported massing their study also were more likely to report cramming (Question 12)—gamma correlation = .75—which provides a cross-validation of responses to these related questions.

Finally, as is evident from responses to students’ regular use of strategies (Question 12), substantial individual differences occurred in reported strategy use. For example, many—but not all—students reported self-testing (71%) or rereading (66%) during study, which was consistent with the popularity of these strategies found by Karpicke et al. (2009). Other strategies, such as asking questions or verbally participating during class, were endorsed less frequently and might indicate neglect of valuable strategies, if such strategies are indeed associated with higher achievement. Thus, we now turn to our main question: Were any of these individual differences in strategy use or scheduling related to GPA?

Relationship between GPA and strategy use

To evaluate whether various strategies from the checklist (Question 12) were related to GPA, we computed a Goodman–Kruskal gamma correlation between whether students endorsed using a given strategy (0, 1) and their reported GPA (where each was assigned the midpoint grade within the category chosen in Question 11).

GPA and Self-testing

As is reported in Fig. 1, self-testing was best reflected by two strategies in Question 12: “test yourself with questions or practice problems” and “use flashcards.” Endorsing the general strategy of testing oneself was significantly related to GPA (gamma = .28, p = .001), whereas using flashcards was not (gamma = −.03, p = .76). This discrepancy between self-testing and flashcards was unexpected and will be addressed in the Discussion section.

Percentages of students reporting regular use of self-testing and flashcards (in the Question 12 strategy checklist, Table 1), displayed as a function of GPA level. Respondents could select as many strategies as desired

Both Kornell and Bjork (2007) and the present survey found that students reported using self-testing for different means (Question 6). Are these differences in how self-testing is used related to student achievement? One possibility is that students who endorse using self-testing as a metacognitive tool (vs. a learning strategy) benefit most from its use, because the metacognitive feedback from self-testing is presumably used to allocate further study time. Although possible, responses to why students tested themselves (Question 6) were not related to GPA. As is shown in Fig. 2, the most common reason for self-testing—endorsed by 50%–60% of students at all GPA levels—was to determine how well information had been learned.

Percentages of students selecting each response option for the reasons one might self-test (Question 6, Table 1), displayed as a function of GPA. Respondents could select only one reason that best represented their habits

GPA and Scheduling

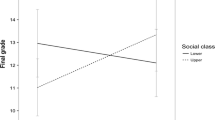

Relevant to scheduling, we examined the responses from Questions 2 (“How do you decide what to study next”), 8 and 9 (time-of-day schedules), 10 (pattern of spacing vs. massing study), and the checklist strategy (Question 12) pertaining to cramming. For the first three questions (2, 8, and 9), we plotted the numbers of students endorsing each response option as a function of GPA. Figure 3 includes values for Question 2, and Fig. 4 includes values for Questions 8 (left panel) and 9 (right panel) pertaining to time-of-day scheduling. Figure 3 shows that although many students are heavily influenced by impending deadlines (what’s due soonest/overdue) when deciding what to study next, this scheduling practice is especially true for low performers. By contrast, although relatively few students overall (13%) schedule their study ahead of time, high performers are more likely to do so. Regarding time of day, Fig. 4 shows similar rates of beliefs about effective study times for students at all GPAs (right panel), but somewhat different patterns of actual studying (left panel) in which the lowest performers are most likely to engage in late-night studying.

Percentages of students selecting each response option for how they decide what to study next (Question 2, Table 1), as a function of GPA. Respondents could select only one answer that best represented their habits

Percentages of students endorsing morning, afternoon, evening, or late-night study times, as a function of GPA. The left panel shows the time of day studying was typically done (Question 8, Table 1), and the right panel shows the time of day that respondents believed is (or would be) most effective for study (Question 9). For each question, respondents could select only one time of day that best represented their habits or beliefs

Regarding how study was scheduled (Questions 10 and 12 about cramming), we correlated the students’ responses to these questions with GPA. Although the correlations were in the expected direction, quite surprisingly, they were not statistically significant for either Question 10 (about spacing study: gamma = .12, p = .15) or 12 (about cramming: gamma = −.16, p = .08). Thus, students who report scheduling practice across sessions (which should be the more effective strategy) did not appear to reap a clear benefit in terms of GPA.

Regression analysis for strategies in Question 12

The strategies from the checklist in Question 12 were only weakly intercorrelated (rs ranged from −.23 to .24), and an exploratory factor analysis did not yield any reliable or interpretable underlying factors. Thus, each strategy was treated as a separate variable rather than being combined with others. Given that the response format was identical for all strategies in Question 12, we evaluated their contributions to GPA by conducting a single regression analysis, which would hold the familywise error rate to .05. The regression analysis was consistent with the conclusions drawn above. The significant standardized regression coefficients were as follows: test yourself (β = .18, p = .003), reread chapters and notes (β = .12, p = .035), make outlines (β = −.12, p = .045,) study with friends (β = −.11, p = .044), and, approaching significance, cramming (β = −.11, p = .064). None of the remaining strategies significantly predicted GPA.

Discussion

Data from this survey replicated the major outcomes of Kornell and Bjork (2007) and Karpicke et al. (2009): College students reported using a self-testing strategy (Fig. 2) largely for monitoring their learning progress, and also reported the use of a variety of other strategies, such as rereading and not studying what they already know. Consistent with expectations from SRL theory, the present study also revealed that some of these strategies are related to college students’ GPAs. Perhaps most impressively, the use of a self-testing strategy—which boosts performance when administered by an experimenter or teacher (Roediger & Butler, 2011)—is also related to student success when used spontaneously for academic learning. As is shown in Fig. 1, almost all of the most successful students (GPA > 3.6) reported using this strategy, and its reported use declined with GPA.

A major issue is the degree to which these benefits of self-testing will generalize to different kinds of tests (e.g., multiple choice, free recall, or essay), different course contents (e.g., biology, psychology, or philosophy), students with differing abilities, and so forth. Current evidence suggests that self-testing has widespread benefits across different kinds of tests, materials, and student abilities. For instance, self-testing by recalling the target information boosts performance on subsequent recall and multiple-choice tests of the target information, and it also boosts performance on tests of comprehension (for reviews, see Roediger & Butler, 2011; Roediger & Karpicke, 2006; and Table S1 from Rawson & Dunlosky, 2011). Nevertheless, it undoubtedly will not be useful for some courses, and if so, our present results may underestimate the power of self-testing, because the composite GPA would reflect courses in which testing would (and would not) matter. On the basis of this rationale and the positive evidence from the present study, future research should examine self-testing and grades for specific classes that vary in the degrees to which they afford self-testing as a potentially effective strategy.

Reported use of rereading was also related to GPA, which might be viewed as surprising, given that rereading does not always improve performance in the laboratory (e.g., Callender & McDaniel, 2009). When used correctly, however, it can boost retention and performance (e.g., Rawson & Kintsch, 2005), and the present rereading–GPA relationship may in part arise from students who read (a lot) versus those who do not read. In contrast to rereading, other reported strategies that presumably are effective did not predict GPA. In particular, the reported use of outlines and collaborative learning demonstrated slightly negative relationships, and the use of diagrams and highlighting were not significantly related to GPA. These outcomes are provocative, because many students believe that these strategies are beneficial when in fact they will not always boost learning. For instance, although studying with friends may have some benefits, students may not always collaborate appropriately when studying together. Also, highlighting by a textbook publisher or instructor can improve performance, but students’ use of highlighting has been shown to yield mixed results, depending on the skill of the user (e.g., Bell & Limber, 2010; Fowler & Barker, 1974). Thus, at least some of these strategies may actually be relatively inert when used by typical students. Based on the present study, however, it would be premature to conclude that these strategies hold absolutely no benefits for student success, because the survey did not measure how often a given student used each strategy and how well the strategies were used. Even self-testing (which was related to GPA) can be used ineffectively, such as when students test themselves by evaluating their familiarity with a concept without trying to recall it from memory (cf. Dunlosky, Rawson, & Middleton, 2005). An exciting avenue for future research will be to develop methods that allow researchers to describe students’ study behavior at a more fine-grained level, such as how often they use self-testing and exactly how they use it to monitor learning.

Although self-testing predicted GPA, the use of flashcards—a popular form of self-testing—unexpectedly did not. In fact, these two strategies were unrelated in the present study (r = .02, p = .68) and might be perceived as different by students. Among students who reported regular use of flashcards, approximately 30% did not report self-testing, which suggests that many flashcard users do not use them to self-test. Flashcards may often be used nonoptimally in vivo, such as when students mindlessly read flashcards without generating responses. Even when they are used appropriately, flashcards may be best suited to committing factual information to memory and not equally effective for studying all types of materials. In contrast, self-testing could also include answering complex questions or solving practice problems, which might encourage deeper processing and yield larger payoffs in performance across many types of materials and courses.

Even those strategies that best predicted GPA were only weakly predictive, which might suggest that students’ strategy choices have little consequence for their grades. Are other factors—such as motivation, interest, intelligence, environment, or competing demands—simply more important? Although possible, several reasons exist for why the correlations observed in the present study are expected to be small, even if some strategies are effective over a wide range of students, tests, and content (e.g., self-testing; Roediger & Butler, 2011). First, different students might have had different courses in mind (e.g., calculus vs. philosophy) when responding to the survey, which would create variability in responding and could obscure strategy–GPA correlations. Future research might overcome this limitation with test–retest methods, longitudinal follow-ups, or more context-specific questions. Second, any strategy could be used well or poorly. This variability in how well strategies are used would obscure how valuable they might be if used ideally. And, third, the present survey asked students to report whether they did or did not use a given strategy regularly (binary responses), rather than how much or how often a strategy was used. Future research will benefit from measuring the degree of usage (a continuous response scale), which might enhance the ability of study strategies to account for variance in performance.

A unique aspect of the present study was the investigation of students’ time management. Differences in scheduling did arise between the highest and lowest achievers, with the lower achievers focusing (a) more on impending deadlines, (b) more on studying late at night, and (c) almost never on planning their study time. Reports of spacing study (vs. cramming) were not significantly related to GPA, even though spaced (vs. massed) practice is known to have a major impact on retention (Cepeda et al., 2006). Although this outcome is surprising, cramming the night (and immediately) before an exam might support relatively good exam performance, even though students who use this strategy might remember little of the content even a short time after the exam. Furthermore, scheduling study sessions in a spaced manner may afford the use of other strategies, which themselves improve student success. Although these ideas are speculative, post-hoc analyses indicated that the reported use of spacing (vs. cramming) was significantly related to the use of more study strategies overall (r = .15, p < .009; combined Question 12 reports) and, in particular, was related to the use of self-testing (r = .11, p = .05) and rereading (r = .15, p = .007). These relationships are small, but they do suggest that spacing may support the use of more effective strategies.

In summary, low performers were especially likely to base their study decisions on impending deadlines rather than planning, and they were also more likely to engage in late-night studying. Although spacing (vs. massing) study was not significantly related to GPA, spacing was associated with the use of more study strategies overall. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, self-testing was a relatively popular strategy and was significantly related to student achievement.

References

Bahrick, H. P., Hall, L. K., & Dunlosky, J. (1993). Reconstructive processing of memory content for high versus low test scores and grades. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 7, 1–10.

Bell, K. E., & Limber, J. E. (2010). Reading skill, textbook marking, and course performance. Literacy Research and Instruction, 49, 56–67.

Callender, A. A., & McDaniel, M. A. (2009). The limited benefits of rereading educational texts. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34, 30–41.

Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 354–380.

Dunlosky, J., & Metcalfe, J. (2009). Metacognition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., & Middleton, E. (2005). What constrains the accuracy of metacomprehension judgments? Testing the transfer-appropriate-monitoring and accessibility hypotheses. Journal of Memory and Language, 52, 551–565.

Fowler, R. L., & Barker, A. S. (1974). Effectiveness of highlighting for retention of text material. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59, 358–364.

Karpicke, J. D., Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L., III. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in student learning: Do students practice retrieval when they study on their own? Memory, 17, 471–479.

Kornell, N., & Bjork, R. A. (2007). The promise and perils of self-regulated study. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14, 219–224.

May, C. P., Hasher, L., & Stoltzfus, E. R. (1993). Optimal time of day and the magnitude of age differences in memory. Psychological Science, 4, 326–330.

McCabe, J. (2011). Metacognitive awareness of learning strategies in undergraduates. Memory & Cognition, 39, 462–476. doi:10.3758/s13421-010-0035-2

McDaniel, M. A., Agarwal, P. K., Huelser, B. J., McDermott, K. B., & Roediger, H. L., III. (2011). Test-enhanced learning in a middle school science classroom: The effects of quiz frequency and placement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103, 399–414.

McDaniel, M. A., & Callender, A. A. (2008). Cognition, memory, and education. In H. L. Roediger (Ed.), Learning and memory: A comprehensive reference. Vol. 2: Cognitive psychology of memory (pp. 235–244). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier.

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J. (1991). A manual for the use of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) (Rep. No. 91-B-004). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

Rawson, K. A., & Dunlosky, J. (2011). Optimizing schedules of retrieval practice for durable and efficient learning: How much is enough? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 140, 283–302. doi:10.1037/a0023956

Rawson, K. A., & Kintsch, W. (2005). Rereading effects depend on time of test. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 70–80.

Roediger, H. L., III, & Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15, 20–27.

Roediger, H. L., III, & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-enhanced learning. Psychological Science, 17, 249–255.

Taraban, R., Maki, W. S., & Rynearson, K. (1999). Measuring study time distributions: Implications for designing computer-based courses. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 31, 263–269.

Winne, P. H., & Hadwin, A. F. (1998). Studying as self-regulated learning. In D. J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A. C. Graesser (Eds.), Metacognition in educational theory and practice (pp. 277–304). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Author note

Many thanks to Katherine Rawson for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. This research was supported by a James S. McDonnell Foundation 21st Century Science Initiative in Bridging Brain, Mind and Behavior Collaborative Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hartwig, M.K., Dunlosky, J. Study strategies of college students: Are self-testing and scheduling related to achievement?. Psychon Bull Rev 19, 126–134 (2012). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-011-0181-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-011-0181-y