Abstract

The loop diuretics furosemide and bumetanide are used widely for the management of fluid overload in both acute and chronic disease states. To date, most pharmacokinetic studies in neonates have been conducted with furosemide and little is known about bumetanide. The aim of this article was to review the published data on the pharmacology of furosemide and bumetanide in neonates and infants in order to provide a critical analysis of the literature, and a useful tool for physicians. The bibliographic search was performed electronically using PubMed and EMBASE databases as search engines and March 2011 was the cutoff point.

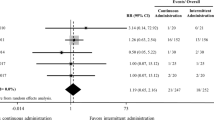

The half-life (t1/2) of both furosemide and bumetanide is considerably longer in neonates than in adults and consequently the clearance (CL) of these drugs is reduced at birth. In healthy volunteers, plasma t1/2 of furosemide ranges from 33 to 100 minutes, whereas in neonates it ranges from 8 to 27 hours. The volume of distribution (Vd) of furosemide undergoes little variation during neonate maturation. The dose of furosemide, administered by intermittent intravenous infusion, is 1mg/kg and may increase to a maximum of 2mg/kg every 24 hours in premature infants and every 12 hours in full-term infants. Comparison of continuous infusion versus intermittent infusion of furosemide showed that the diuresis is more controlled with fewer hemodynamic and electrolytic variations during continuous infusion. The appropriate infusion rate of furosemide ranges from 0.1 to 0.2mg/kg/h and when the diuresis is <1mL/kg/h the infusion rate may be increased to 0.4mg/kg/h. Treatment with theophylline before administration of furosemide results in a significant increase of urine flow rate. Bumetanide is more potent than furosemide and its dose after intermittent intravenous infusion ranges from 0.005 to 0.1mg/kg every 24 hours. The t1/2 of bumetanide in neonates ranges from 1.74 to 7.0 hours. Up to now, no data are available on the continuous infusion of bumetanide.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is used for a variety of indications including sepsis, persistent pulmonary hypertension, meconium aspiration syndrome, cardiac defects and congenital diaphragmatic hernia. There are two studies of furosemide in neonates undergoing ECMO and only one on the pharmacokinetics of bumetanide under ECMO. When ECMO was conducted for 72 hours, the total amount of furosemide administered was 7.0mg/kg, and the urine production in the 3 days of treatment was about 6mL/kg/h, which is the target value. The t1/2 of bumetanide in neonates during ECMO was extremely variable. CL, t1/2, and Vd were 0.63mL/min/kg, 13.2 hours, and 0.45L/kg, respectively. Furosemide may be administered by inhalation and inhibits the bronco-constrictive effect of exercise, cold air ventilation and antigen challenge. However, inhaled furosemide is not active in infants with viral bronchiolitis and its effect on broncho-pulmonary dysplasia is still uncertain. Furosemide does not significantly increase the risk of failure of patent ductus arteriosus closure when indomethacin or ibuprofen have been co-administered. Infants with low birth weight treated long-term with furosemide are at risk for the development of intrarenal calcification. Furosemide therapy above 10mg/kg bodyweight cumulative dose had a 48-fold increased risk of nephrocalcinosis. The use of furosemide in combination with indomethacin increased the incidence of acute renal failure. The maturation of the kidney governs the pharmacokinetics of furosemide and bumetanide in the infant. CL and t1/2 are influenced by development, and this must be taken into consideration when planning a dosage regimen with these drugs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Aperia A, Broberger O, Elinder G, et al. Postnatal development of renal function in pre-term and full-term infants. Acta Paediatr Scand 1981; 70: 183–7.

Arant Jr BS. Developmental patterns of renal functional maturation compared in the human neonate. J Pediatr 1978; 92: 705–12.

Eades SK, Christensen ML. The clinical pharmacology of loop diuretics in the pediatric patient. Pediatr Nephrol 1998; 12: 603–16.

Faa G, Gerosa C, Fanni D, et al. Marked interindividual variability in renal maturation of preterm infants: lessons from autopsy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2010; 23 Suppl. 3: 129–33

Leake RD, Trygstad CW, Oh W. Inulin clearance in the newborn infant: relationship to gestational and postnatal age. Pediatr Res 1976; 10: 759–62.

Mirochnick MH, Miceli JJ, Kramer PA, et al. Furosemide pharmacokinetics in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr 1988; 112: 653–7.

Mirochnick MH, Miceli JJ, Kramer PA, et al. Renal response to furosemide in very low birth weight infants during chronic administration. Dev Pharmacol Ther 1990; 15: 1–7.

Schoemaker RC, van der Vorst MM, van Heel IR, et al. Pediatric Pharmacology Network. Development of an optimal furosemide infusion strategy in infants with modeling and simulation. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2002; 72: 383–90.

Sulyok E, Varga F, Györy E, et al. On the mechanisms of renal sodium handling in newborn infants. Biol Neonate 1980; 37: 75–9.

Witte MK, Stork JE, Blumer JL. Diuretic therapeutics in the pediatric patient. Am J Cardiol 1986; 57: 44A–53A

Baliga R, Lewy JE. Pathogenesis and treatment of edema. Pediatr Clin North Am 1987; 34: 639–48.

Chennavasin P, Seiwell R, Brater DC, et al. Pharmacodynamic analysis of the furosemide-probenecid interaction in man. Kidney Int 1979; 16: 187–95.

Sjöström PA, Kron BG, Odlind BG. Determinants of furosemide delivery to its site of action. Clin Nephrol 1995; 43 Suppl. 1: S38–41

Ponto LL, Schoenwald RD. Furosemide (frusemide): a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic review (part I). Clin Pharmacokinet 1990; 18: 381–408.

Brater DC. Clinical pharmacology of loop diuretics. Drugs 1991; 41 Suppl. 3: 14–22

Tuck S, Morselli P, Broquaire M, et al. Plasma and urinary kinetics of furosemide in newborn infants. J Pediatr 1983; 103: 481–5.

Aranda JV, Perez J, Sitar DS, et al. Pharmacokinetic disposition and protein binding of furosemide in newborn infants. J Pediatr 1978; 93: 507–11.

Aranda JV, Lambert C, Perez J, et al. Metabolism and renal elimination of furosemide in the newborn infant. J Pediatr 1982; 101: 777–81.

Peterson RG, Simmons MA, Rumack BH, et al. Pharmacology of furosemide in the premature newborn infant. J Pediatr 1980; 97: 139–43.

Sullivan JE, Witte MK, Yamashita TS, et al. Pharmacokinetics of bumetanide in critically ill infants. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1996; 60: 405–13.

Sullivan JE, Witte MK, Yamashita TS, et al. Analysis of the variability in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of bumetanide in critically ill infants. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1996; 60: 414–23.

Vert P, Broquaire M, Legagneur M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of furosemide in neonates. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1982; 22: 39–45.

Wells TG, Fasules JW, Taylor BJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of bumetanide in neonates treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr 1992; 12: 974–80.

Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Benet LZ. Furosemide pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in health and disease: an update. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 1989; 17: 1–46.

Young TE, Mangum B. Antimicrobials. In: Neofax: a manual of drugs used in neonatal care. 23rd ed. Montvale (NJ): Thomson Reuters, 2010: 1–99

Lopez-Samblas AM, Adams JA, Goldberg RN, et al. The pharmacokinetics of bumetanide in the newborn infant. Biol Neonate 1997; 72: 265–72.

Brater DC. Determinants of the overall response to furosemide: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Fed Proc 1983; 42: 1711–3.

Tuzel IH. Comparison of adverse reactions to bumetanide and furosemide. J Clin Pharmacol 1981; 21: 615–9.

Ramsay LE, McInnes GT, Hettiarachchi J, et al. Bumetanide and frusemide: a comparison of dose-response curves in healthy men. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1978; 5: 243–7.

Asbury MJ, Gatenby PB, O’Sullivan S, et al. Bumetanide: potent new ‘loop’ diuretic. BMJ 1972; 1:211–3

Turmen T, Thom P, Louridas AT, et al. Protein binding and bilirubin displacing properties of bumetanide and furosemide. J Clin Pharmacol 1982; 22: 551–6.

Robertson A, Karp W. Albumin binding of bumetanide. Dev Pharmacol Ther 1986; 9: 241–8.

Ross BS, Pollak A, Oh W. The pharmacologic effects of furosemide therapy in the low-birth-weight infant. J Pediatr 1978; 92: 149–52.

Woo WC, Dupont C, Collinge J, et al. Effects of furosemide in the newborn. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1978; 23: 266–71.

Rane A, Villeneuve JP, Stone WJ, et al. Plasma binding and disposition of furosemide in the nephrotic syndrome and in uremia. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1978; 24: 199–207.

Rupp W. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of Lasix. Scott Med J 1974; 19 Suppl. 1: 5–13

Beermann B, Dalén E, Lindström B, et al. On the fate of furosemide in man. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1975; 9: 51–61.

Beermann B, Dalén E, Lindström B. Elimination of furosemide in healthy subjects and in those with renal failure. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1977; 22: 70–8.

Calesnick B, Christensen JA, Richter M. Absorption and excretion of furosemide-S35 in human subjects. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1966; 123: 17–22.

Hook JB, Williamson HE. Influence of probenecid and alterations in acid-base balance of the saluretic activity of furosemide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1965; 149: 404–8.

Prandota J, Houin G. Kinetics of urinary furosemide elimination in infants. Dev Pharmacol Ther 1984; 7: 273–84.

Ward A, Heel RC. Bumetanide: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use. Drugs 1984; 28: 426–64.

Bahrami KR, Van Meurs KP. ECMO for neonatal respiratory failure. Semin Perinatol 2005; 29: 15–23.

van der Vorst MM, Wildschut E, Houmes RJ, et al. Evaluation of furosemide regimens in neonates treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care 2006; 10: 1–8.

van der Vorst MM, Kist-van Holthe JE, den Hartigh J, et al. Absence of tolerance and toxicity to high-dose continuous intravenous furosemide in haemodynamically unstable infants after cardiac surgery. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007; 64: 796–803.

Lochan SR, Adeniyi-Jones S, Assadi FK, et al. Coadministration of theophylline enhances diuretic response to furosemide in infants during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Pediatr 1998; 133: 86–9.

Erley CM, Duda SH, Schlepckow S, et al. Adenosine antagonist theophylline prevents the reduction of glomerular filtration rate after contrast media application. Kidney Int 1994; 45: 1425–31.

Kugelman A, Durand M, Garg M. Pulmonary effect of inhaled furosemide in ventilated infants with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics 1997; 99: 71–5.

Bar A, Srugo I, Amirav I, et al. Inhaled furosemide in hospitalized infants with viral bronchiolitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Pediatr Pulmonol 2008; 43: 261–7.

Pai VB, Nahata MC. Aerosolized furosemide in the treatment of acute respiratory distress and possible bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm neonates. Ann Pharmacother 2000; 34: 386–92.

Rastogi A, Luayon M, Ajayi OA, et al. Nebulized furosemide in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr 1994; 125 (6 Pt 1): 976–9

Prabhu VG, Keszler M, Dhanireddy R. Pulmonary function changes after nebulised and intravenous frusemide in ventilated premature infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1997; 77: F32–5

Ohki Y, Nako Y, Koizumi T, et al. The effect of aerosolized furosemide in infants with chronic lung disease. Acta Paediatr 1997; 86: 656–60.

Gulbis BE, Spencer AP. Efficacy and safety of a furosemide continuous infusion following cardiac surgery. Ann Pharmacother 2006; 40: 1797–803.

Luciani GB, Nichani S, Chang AC, et al. Continuous versus intermittent furosemide infusion in critically ill infants after open heart operations. Ann Thorac Surg 1997; 64: 1133–9.

Reiter PD, Makhlouf R, Stiles AD. Comparison of 6-hour infusion versus bolus furosemide in premature infants. Pharmacotherapy 1998; 18: 63–8.

van der Vorst MM, den Hartigh J, Wildschut E, et al. An exploratory study with an adaptive continuous intravenous furosemide regimen in neonates treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care 2007; 11: R111

van der Vorst MM, Ruys-Dudok van Heel I, Kist-van Holthe JE, et al. Continuous intravenous furosemide in haemodynamically unstable children after cardiac surgery. Intensive Care Med 2001; 27: 711–5.

Lee BS, Byun SY, Chung ML, et al. Effect of furosemide on ductal closure and renal function in indomethacin-treated preterm infants during the early neonatal period. Neonatology 2010; 98: 191–9.

Chevalier RL. Developmental renal physiology of the low birth weight preterm newborn. J Urol 1996; 156: 714–9.

Sulyok E, Varga F, Németh M, et al. Furosemide-induced alterations in the electrolyte status, the function of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, and the urinary excretion of prostaglandins in newborn infants. Pediatr Res 1980; 14: 765–8.

Friedman Z, Demers LM, Marks KH, et al. Urinary excretion of prostaglandin E following the administration of furosemide and indomethacin to sick low-birth-weight infants. J Pediatr 1978; 93: 512–5.

Brion LP, Campbell DE. Furosemide for symptomatic patent ductus arteriosus in indomethacin-treated infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001; (3):CD001148

Andriessen P, Struis NC, Niemarkt H, et al. Furosemide in preterm infants treated with indomethacin for patent ductus arteriosus. Acta Paediatr 2009; 98: 797–803.

Green TP, Thompson TR, Johnson DE, et al. Furosemide promotes patent ductus arteriosus in premature infants with the respiratory-distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 1983 31; 308: 743–8.

Chotigeat U, Jirapapa K, Layangkool T. A comparison of oral ibuprofen and intravenous indomethacin for closure of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants. J Med Assoc Thai 2003; 86 Suppl. 3: S563–9

Borradori C, Fawer CL, Buclin T, et al. Risk factors of sensorineural hearing loss in preterm infants. Biol Neonate 1997; 71: 1–10.

Rybak LP. Pathophysiology of furosemide ototoxicity. J Otolaryngol 1982; 11: 127–33.

Gimpel C, Krause A, Franck P, et al. Exposure to furosemide as the strongest risk factor for nephrocalcinosis in preterm infants. Pediatr Int 2010; 52: 51–6.

Downing GJ, Egelhoff JC, Daily DK, et al. Furosemide-related renal calcifications in the premature infant: a longitudinal ultrasonographic study. Pediatr Radiol 1991; 21: 563–5.

Kenney IJ, Aiken CG, Lenney W. Frusemide-induced nephrocalcinosis in very low birth weight infants. Pediatr Radiol 1988; 18: 323–5.

Myracle MR, McGahan JP, Goetzman BW, et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of renal calcification in infants on chronic furosemide therapy. J Clin Ultrasound 1986; 14: 281–7.

Pearse DM, Kaude JV, Williams JL, et al. Sonographic diagnosis of furosemide-induced nephrocalcinosis in newborn infants. J Ultrasound Med 1984; 3: 553–6.

Hufnagle KG, Khan SN, Penn D, et al. Renal calcifications: a complication of long-term furosemide therapy in preterm infants. Pediatrics 1982; 70: 360–3.

Kahle KT, Staley KJ. The bumetanide-sensitive Na-K-2Cl cotransporter NKCC1 as a potential target of a novel mechanism-based treatment strategy for neonatal seizures. Neurosurg Focus 2008; 25: E22

Borgia F, De Pasquale L, Cacace C, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn: be aware of hypercalcaemia. J Paediatr Child Health 2006; 42: 316–8.

Ghirri P, Bottone U, Coccoli L, et al. Symptomatic hypercalcemia in the first months of life: calcium-regulating hormones and treatment. J Endocrinol Invest 1999; 22: 349–53.

Nair S, Nair SG, Borade A, et al. Hypercalcemia and metastatic calcification in a neonate with subcutaneous fat necrosis. Indian J Pediatr 2009; 76:1155–7

Poca MA, Sahuquillo J. Short-term medical management of hydrocephalus. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2005; 6: 1525–38.

Shinnar S, Gammon K, Bergman Jr EW, et al. Management of hydrocephalus in infancy: use of acetazolamide and furosemide to avoid cerebrospinal fluid shunts. J Pediatr 1985; 107 (1): 31–7.

Prandota J. Clinical pharmacology of furosemide in children: a supplement. Am J Ther 2001; 8:275–89

Horinek D, Cihar M, Tichy M. Current methods in the treatment of post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus in infants. Bratisl Lek Listy 2003; 104: 347–51.

Whitelaw A, Kennedy CR, Brion LP. Diuretic therapy for newborn infants with posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001; (2): CD002270

Kennedy CR, Ayers S, Campbell MJ, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of acetazolamide and furosemide in posthemorrhagic ventricular dilation in infancy: follow-up at 1 year. Pediatrics 2001; 108: 597–607.

Libenson MH, Kaye EM, Rosman NP, et al. Acetazolamide and furosemide for posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus of the newborn. Pediatr Neurol 1999; 20: 185–91.

Gaskill SJ, Marlin AE, Rivera S. The subcutaneous ventricular reservoir: an effective treatment for posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus. Childs Nerv Syst 1988; 4: 291–5.

Pacifici GM, Rane A. Distribution of UDP-glucuronyltransferase in different human foetal tissues. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1982; 13: 732–5.

Pacifici GM, Sawe J, Kager L, et al. Morphine glucuronidation in human fetal and adult liver. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1982; 22: 553–8.

Cappiello M, Giuliani L, Rane A, et al. 5′-Diphosphoglucuronic acid (UDPGA) in the human fetal liver, kidney and placenta. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokin 2000; 25: 161–3.

Burg M, Stoner L, Cardinal J, et al. Furosemide effect on isolated perfused tubules. Am J Physiol 1973; 225: 119–24.

Martin SJ, Danziger LH. Continuous infusion of loop diuretics in the critically ill: a review of the literature. Crit Care Med 1994; 22: 1323–9.

Pivac N, Rumboldt Z, Sardelić S, et al. Diuretic effects of furosemide infusion versus bolus injection in congestive heart failure. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res 1998; 18: 121–8.

Schuller D, Lynch JP, Fine D. Protocol-guided diuretic management: comparison of furosemide by continuous infusion and intermittent bolus. Crit Care Med 1997; 25: 1969–75.

Ad N, Suyderhoud JP, Kim YD, et al. Benefits of prophylactic continuous infusion of furosemide after the maze procedure for atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002; 123: 232–6.

Mojtahedzadeh M, Salehifar E, Vazin A, et al. Comparison of hemodynamic and biochemical effects of furosemide by continuous infusion and intermittent bolus in critically ill patients. J Infus Nurs 2004; 27: 255–61.

Klinge JM, Scharf J, Hofbeck M, et al. Intermittent administration of furosemide versus continuous infusion in the postoperative management of children following open heart surgery. Intensive Care Med 1997; 23: 693–7.

Singh NC, Kissoon N, al Mofada S, et al. Comparison of continuous versus intermittent furosemide administration in postoperative pediatric cardiac patients. Crit Care Med 1992; 20: 17–21.

Bartlett RH, Gazzaniga AB, Jefferies MR, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) cardiopulmonary support in infancy. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs 1976; 22: 80–93.

Kim ES, Stolar CJ. ECMO in the newborn. Am J Perinatol 2000; 17: 345–56.

Buck ML. Pharmacokinetic changes during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: implications for drug therapy of neonates. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003; 42: 403–17.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the Ministry of the University and Scientific and Technologic Research (Rome, Italy).

The author has no potential conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pacifici, G.M. Clinical Pharmacology of the Loop Diuretics Furosemide and Bumetanide in Neonates and Infants. Pediatr Drugs 14, 233–246 (2012). https://doi.org/10.2165/11596620-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11596620-000000000-00000