Abstract

Background: Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is a common condition. Some of the most widely prescribed medications are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), based on the hypothesized role of serotonin in the production of PMS symptoms. PMS sufferers, especially those experiencing mild to moderate symptoms, are often reluctant to take this form of medication and instead buy over-the-counter preparations to treat their symptoms, for which the evidence base with regard to efficacy is limited. Hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) influences the serotonergic system. As such, this widely available herbal remedy deserves attention as a PMS treatment.

Objective: To investigate the effectiveness of Hypericum perforatum on symptoms of PMS.

Study design: This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study was conducted between November 2005 and June 2007.

Setting: Institute of Psychological Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK.

Participants: 36 women aged 18–45 years with regular menstrual cycles (25–35 days), who were prospectively diagnosed with mild PMS.

Intervention: Women who remained eligible after three screening cycles (n = 36) underwent a two-cycle placebo run-in phase. They were then randomly assigned to receive Hypericum perforatum tablets 900 mg/day (standardized to 0.18% hypericin; 3.38% hyperforin) or identical placebo tablets for two menstrual cycles. After a placebo-treated washout cycle, the women crossed over to receive placebo or Hypericum perforatum for two additional cycles.

Main outcome measures: Symptoms were rated daily throughout the trial using the Daily Symptom Report. Secondary outcome measures were the State Anxiety Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory, Aggression Questionnaire and Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Plasma hormone (follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH], luteinizing hormone [LH], estradiol, progesterone, prolactin and testosterone) and cytokine (interleukin [IL]-1β, IL-6, IL-8, interferon [IFN]-γ and tumour necrosis factor [TNF]-α) levels were measured in the follicular and luteal phases during Hypericum perforatum and placebo treatment.

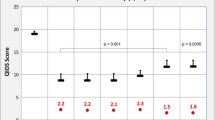

Results: Hypericum perforatum was statistically superior to placebo in improving physical and behavioural symptoms of PMS (p < 0.05). There were no significant effects of Hypericum perforatum compared with placebo treatment for mood- and pain-related PMS symptoms (p > 0.05). Plasma hormone (FSH, LH, estradiol, progesterone, prolactin and testosterone) and cytokine (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IFNγ and TNFα) levels, and weekly reports of anxiety, depression, aggression and impulsivity, also did not differ significantly during the Hypericum perforatum and placebo cycles (p > 0.05).

Conclusion: Daily treatment with Hypericum perforatum was more effective than placebo treatment for the most common physical and behavioural symptoms associated with PMS. As proinflammatory cytokine levels did not differ significantly between Hypericum perforatum and placebo treatment, these beneficial effects are unlikely to be produced through this mechanism of action alone. Further work is needed to determine whether pain- and mood-related PMS symptoms benefit from longer treatment duration.

Trial registration number (International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register) ISRCTN31487459

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Freeman EW. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: definitions and diagnosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003 Aug; 28Suppl. 3: 25–37

Halbreich U, Backstrom T, Eriksson E, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for premenstrual syndrome and guidelines for their quantification for research studies. Gynecol Endocrinol 2007 Mar; 23(3): 123–30

Reed SC, Levin FR, Evans SM. Changes in mood, cognitive performance and appetite in the late luteal and follicular phases of the menstrual cycle in women with and without PMDD (premenstrual dysphoric disorder). Horm Behav 2008 Jun; 54(1): 185–93

Borenstein JE, Dean BB, Yonkers KA, et al. Using the daily record of severity of problems as a screening instrument for premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 2007 May; 109(5): 1068–75

Johnson SR. Premenstrual syndrome, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and beyond: a clinical primer for practitioners. Obstet Gynecol 2004 Oct; 104(4): 845–59

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; Department of Health and Human Services, 1994

Steiner M, Wilkins A. Diagnosis and assessment of premenstrual dysphoria. Psychiatr Ann 1996 Sep; 26(9): 571–5

Ussher JM. Processes of appraisal and coping in the development and maintenance of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Community Appl Soc Psychol 2002 Sep–Oct; 12(5): 309–22

Steiner M, Born L. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. CNS Drugs 2000 Apr; 13(4): 287–304

Steiner M, Pearlstein T. Premenstrual dysphoria and the serotonin system: pathophysiology and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61Suppl. 12: 17–21

Ussher JM. The ongoing silencing of women in families: an analysis and rethinking of premenstrual syndrome and therapy. J Fam Ther 2003 Nov; 25(4): 388–405

Ainscough CE. Premenstrual emotional changes: a prospective study of symptomatology in normal women. J Psychosom Res 1990; 34(1): 35–45

Gallant SJ, Popiel DA, Hoffman DM, et al. Using daily ratings to confirm premenstrual syndrome/late luteal phase dysphoric disorder: part II. What makes a ‘real’ difference? Psychosom Med 1992 Mar–Apr; 54(2): 167–81

Ussher JM. The role of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the subjectification of women. J Med Humanit 2003 Jun; 24(1–2): 131–46

Bancroft J, Williamson L, Warner P, et al. Perimenstrual complaints in women complaining of PMS, menorrhagia, and dysmenorrhea: toward a dismantling of the premenstrual syndrome. Psychosom Med 1993 Mar–Apr; 55(2): 133–45

Morse CA, Dennerstein L, Varnavides K, et al. Menstrual cycle symptoms: comparison of a non-clinical sample with a patient group. J Affect Disord 1988 Jan–Feb; 14(1): 41–50

Dimmock PW, Wyatt KM, Jones PW, et al. Efficacy of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review. Lancet 2000 Sep; 356(9236): 1131–6

Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, O’Brien PM. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002; (4): CD001396

Connolly M. Premenstrual syndrome: an update on definitions, diagnosis and management. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2001; 7(6): 469–77

Bendich A. The potential for dietary supplements to reduce premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms. J Am Coll Nutr 2000 Feb; 19(1): 3–12

Canning S, Waterman M, Dye L. Dietary supplements and herbal remedies for premenstrual syndrome (PMS): a systematic research review of the evidence for their efficacy. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2006 Nov; 24(4): 363–78

Domoney CL, Vashisht A, Studd JW. Premenstrual syndrome and the use of alternative therapies. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003 Nov; 997: 330–40

Eriksson E, Endicott J, Andersch B. New perspectives on the treatment of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Arch Womens Ment Health 2002; 4(4): 111–9

Blake F, Salkovskis P, Gath D, et al. Cognitive therapy for premenstrual syndrome: a controlled trial. J Psychosom Res 1998 Oct; 45(4): 307–18

Hunter M, Ussher J, Cariss M, et al. A randomised comparison of psychological (cognitive behaviour therapy), medical (fluoxetine) and combined treatment for women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2002 Sep; 23: 193–9

Kirkby RJ. Changes in premenstrual symptoms and irrational thinking following cognitive-behavioral coping skills training. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994 Oct; 62(5): 1026–32

Morse CA, Dennerstein L, Farrell E, et al. A comparison of hormone therapy, coping skills training, and relaxation for the relief of premenstrual syndrome. J Behav Med 1991 Oct; 14(5): 469–89

Goodale IL, Domar AD, Benson H. Alleviation of premenstrual syndrome symptoms with the relaxation response. Obstet Gynecol 1990 Apr; 74(4): 649–55

Anson O. Exploring the bio-psycho-social approach to premenstrual experiences. Soc Sci Med 1999 Jul; 49(1): 67–80

Keye Jr WR, Trunnell EP. A biopsychosocial model of premenstrual syndrome. Int J Fertil 1986 Sep–Oct; 31(4): 259–62

Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ. Models for the development and expression of symptoms in premenstrual syndrome. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1989 Mar; 12(1): 53–68

Ussher JM, Hunter M, Cariss M. A women-centred psychological intervention for premenstrual symptoms, drawing on cognitive-behavioural and narrative therapy. Clin Psychol Psychother 2002; 9(5): 319–31

Walker AF. Theory and methodology in premenstrual syndrome research. Soc Sci Med 1995 Sep; 41(6): 793–800

Bäckström T, Carstensen H. Estrogen and progesterone in plasma in relation to premenstrual tension. J Steroid Biochem 1974 May; 5(3): 257–60

Horrobin DF. The role of essential fatty acids and prostaglandins in the premenstrual syndrome. J Reprod Med 1983 Jul; 28(7): 465–8

Shamberger RJ. Calcium, magnesium, and other elements in the red blood cells and hair of normals and patients with premenstrual syndrome. Biol Trace Elem Res 2003 Aug; 94(2): 123–9

Thys-Jacobs S, Alvir MJ. Calcium-regulating hormones across the menstrual cycle: evidence of a secondary hyperparathyroidism in women with PMS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995 Jul; 80(7): 2227–32

Abraham GE, Lubran MM. Serum and red cell magnesium levels in patients with premenstrual tension. Am J Clin Nutr 1981 Nov; 34(11): 2364–6

Brush MG, Watson SJ, Horrobin DF, et al. Abnormal essential fatty acid levels in plasma of women with premenstrual syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1984 Oct; 150(4): 363–6

Carroll BJ, Steiner M. The psychobiology of premenstrual dysphoria: the role of prolactin. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1978 Apr; 3(2): 171–80

Halbreich U. Premenstrual dysphoric disorders: a diversified cluster of vulnerability traits to depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997 Mar; 95(3): 169–76

Rapkin AJ. The role of serotonin in premenstrual syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1992 Sep; 35(3): 629–36

Ashby CR, Carr LA, Cook CL, et al. Alteration of platelet serotonergic mechanisms and monoamine oxidase activity on premenstrual syndrome. Biol Psychiatry 1988 Jun; 24(2): 225–33

Rapkin AJ, Edelmuth E, Chang LC, et al. Whole-blood serotonin in premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 1987 Oct; 70(4): 533–7

Rasgon N, McGuire M, Tanavoli S, et al. Neuroendocrine response to an intravenous L-tryptophan challenge in women with premenstrual syndrome. Fertil Steril 2000 Jan; 73(1): 144–9

Taylor DL, Mathew RJ, Ho BT, et al. Serotonin levels and platelet uptake during premenstrual tension. Neuropsychobiology 1984; 12(1): 16–8

Cleare AJ, Bond AJ. The effects of tryptophan depletion and enhancement on subjective and behavioural aggression in normal subjects. Psychopharmacology 1995 Mar; 118(1): 72–81

Ho HP, Olsson M, Westberg L, et al. The serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine reduces sex steroid-related aggression in female rats: an animal model of premenstrual irritability? Neuropsychopharmacology 2001 May; 24(5): 502–10

Hirschfeld RM. History and evolution of the monoamine hypothesis of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61Suppl. 6: 4–6

Kahn RS, van Praag HM, Wetzler S, et al. Serotonin and anxiety revisited. Biol Psychiatry 1988 Jan; 23(2): 189–208

Russo S, Kema IP, Haagsma EB, et al. Irritability rather than depression during interferon treatment is linked to increased tryptophan catabolism. Psychosom Med 2005 Sep–Oct; 67(5): 773–7

Bonaccorso S, Marino V, Puzella A, et al. Increased depressive ratings in patients with hepatitis C receiving interferon-alpha-based immunotherapy are related to interferon-alpha-induced changes in the serotonergic system. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002 Feb; 22(1): 86–90

Gemma C, Imeri L, De Simoni MG, et al. Interleukin-1 induces changes in sleep, brain temperature, and serotonergic metabolism. Am J Physiol 1997 Feb; 272 (2 Pt 2): R601–6

Gemma C, Imeri L, Opp MR. Serotonergic activation stimulates the pituitary-adrenal axis and alters interleukin-1 (IL-1) mRNA expression in rat brain. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003 Oct; 28(7): 875–84

Linthorst AC, Flachskamm C, Holsboer F, et al. Local administration of recombinant human interleukin-1 beta in the rat hippocampus increases serotonergic neurotransmission, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis activity, and body temperature. Endocrinology 1994 Aug; 135(2): 520–32

O’Brien SM, Scott LV, Dinan TG. Cytokines: abnormalities in major depression and implications for pharmacological treatment. Hum Psychopharmacol 2004 Aug; 19(6): 397–403

Pousset F, Fournier J, Legoux P, et al. Effect of serotonin on cytokine mRNA expression in rat hippocampal astrocytes. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1996 May; 38(1): 54–62

Silverman DH, Imam K, Karnovsky ML. Muramyl peptide/ serotonin receptors in brain-derived preparations. Pept Res 1989 Sep–Oct; 2(5): 338–44

Gorai I, Taguchi Y, Chaki O, et al. Serum soluble inter-leukin-6 receptor and biochemical markers of bone metabolism show significant variations during the menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998 Feb; 83(2): 326–32

Vrieze A, Postma DS, Kerstjens HA. Perimenstrual asthma: a syndrome without known cause or cure. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003 Aug; 112(2): 271–82

Cannon JG, Dinarello CA. Increased plasma interleukin-1 activity in women after ovulation. Science 1985 Mar; 227(4691): 1247–9

Polan ML, Kuo A, Loukides J, et al. Cultured human luteal peripheral monocytes secrete increased levels of interleukin-1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1990 Feb; 70(2): 480–4

Konecna L, Yan MS, Miller LE, et al. Modulation of IL-6 production during the menstrual cycle in vivo and in vitro. Brain Behav Immun 2000 Mar; 14(1): 49–61

Maes M, Meltzer H, Bosmans E, et al. Increased plasma concentrations of interleukin-6, soluble interleukin-6 receptor, soluble interleukin-2 receptor and transferrin receptor in major depression. J Affect Disord 1995 Aug; 34(4): 301–9

Schlatter J, Ortuno F, Cervera-Enguix S. Differences in interleukins’ patterns between dysthymia and major depression. Eur Psychiatry 2001 Aug; 16(5): 317–9

Connor TJ, Song C, Leonard BE, et al. An assessment of the effects of central interleukin-1 beta, -2, -6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha administration on some behavioural, neurochemical, endocrine and immune parameters in the rat. Neuroscience 1998 Jun; 84(3): 923–33

Kronfol Z, Remick DG. Cytokines and the brain: implications for clinical psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 2000 May; 157(5): 683–94

Martelletti P, Granata M, Giacovazzo M. Serum interleukin-1 beta is increased in cluster headache. Cephalalgia 1993 Oct; 13(5): 343–5

Kapas L, Krueger JM. Tumor necrosis factor-beta induces sleep, fever, and anorexia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 1992 Sep; 263 (3 Pt 2): 703–7

Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, Lin HM, et al. IL-6 and its circadian secretion in humans. Neuroimmunomodulation 2005 May; 12(3): 131–40

Reichenberg A, Yirmiya R, Schuld A, et al. Cytokine-associated emotional and cognitive disturbances in humans. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001 May; 58(5): 445–52

Menkes DB, MacDonald JA. Interferons, serotonin and neurotoxicity. Psychol Med 2000 Mar; 30(2): 259–68

Maes M. The immunoregulatory effects of antidepressants. Hum Psychopharmacol 2001 Jan; 16(1): 95–103

Sluzewska A, Rybakowski JK, Laciak M, et al. Interleukin-6 serum levels in depressed patients before and after treatment with fluoxetine. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1995 Jul; 762: 474–6

Van Gool AR, Fekkes D, Kruit WH, et al. Serum amino acids, biopterin and neopterin during long-term immunotherapy with interferon-alpha in high-risk melanoma patients. Psychiatry Res 2003 Jul; 119(1–2): 125–32

Calapai G, Crupi A, Firenzuoli F, et al. Serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine involvement in the anti-depressant action of hypericum perforatum. Pharmacopsychiatry 2001 Mar; 34(2): 45–9

Muller WE, Singer A, Wonnemann M, et al. Hyperforin represents the neurotransmitter reuptake inhibiting constituent of hypericum extract. Pharmacopsychiatry 1998 Jun; 31Suppl. 1: 16–21

Teufel-Mayer R, Gleitz J. Effects of long-term administration of hypericum extracts on the affinity and density of the central serotonergic 5-HT1 A and 5-HT2 A receptors. Pharmacopsychiatry 1997 Sep; 30Suppl. 2: 113–6

Fiebich BL, Hollig A, Lieb K. Inhibition of substance P-induced cytokine synthesis by St. John’s wort extracts. Pharmacopsychiatry 2001 Jul; 34Suppl. 1: S26–8

Thiele B, Brink I, Ploch M. Modulation of cytokine expression by hypericum extract. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1994 Oct; 7Suppl. 1: S60–2

Clement K, Covertson CR, Johnson MJ, et al. St John’s wort and the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a systematic review. Holist Nurs Pract 2006 Jul–Aug; 20(4): 197–203

Gaster B, Holroyd J. St John’s wort for depression: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2000 Jan; 160(2): 152–8

Kim HL, Streltzer J, Goebert D. St John’s wort for depression: a meta-analysis of well-defined clinical trials. J Nerv Ment Dis 1999 Sep; 187(9): 532–8

Williams Jr JW, Mulrow CD, Chiquette E, et al. A systematic review of newer pharmacotherapies for depression in adults: evidence report summary. Ann Intern Med 2000 May; 132(9): 743–56

Agha-Hosseini M, Kashani L, Aleyaseen A, et al. Crocus sativus L. (saffron) in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: a double-blind, randomised and placebo-controlled trial. BJOG 2008 Mar; 115(4): 515–9

Hicks SM, Walker AF, Gallagher J, et al. The significance of “nonsignificance” in randomized controlled studies: a discussion inspired by a double-blinded study on St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum L.) for premenstrual symptoms. J Altern Complement Med 2004 Dec; 10(6): 925–32

Steiner M, Steinberg S, Stewart D, et al. Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. N Engl J Med 1995 Jun; 332(23): 1529–34

Pakgohar M, Mehran A, Salehi MS, et al. Comparison of hypericum perforatum and placebo in treatment of physical symptoms of premenstrual syndrome [in Persian]. HAYAT J Tehran Fac Nurs Midwifery 2004; 10(22): 99

Pakgohar M, Ahmadi M, Surmaghi MH, et al. Effect of Hypericum perforatum L. for treatment of premenstrual syndrome [in Persian]. J Med Plants 2005 Sep; 4(15): 33–42

Bennett Jr DA, Phun L, Polk JF, et al. Neuropharmacology of St. John’s wort (Hypericum). Ann Pharmacother 1998 Nov;32(11): 1201–8

Miller AL. St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): clinical effects on depression and other conditions. Altern Med Rev 1998 Feb; 3(1): 18–26

Montgomery S, Hubener W, Gregoleit H. Efficacy and tolerability of St John’s wort extract compared with placebo in patients with a mild to moderate depressive disorder. Phytomedicine 2000; 7Suppl. 2: 107

Shelton RC, Keller MB, Gelenberg A, et al. Effectiveness of St John’s wort in major depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001 Apr; 285(15): 1978–86

Freeman EW, DeRubeis RJ, Rickels K. Reliability and validity of a daily diary for premenstrual syndrome. Psychiatry Res 1996 Nov; 65(2): 97–106

Hamilton JA, Parry BL, Alagna S, et al. Premenstrual mood changes: a guide to evaluation and treatment. Psychiatr Ann 1984 Jun; 14(6): 426–35

NIMH Workshop on Pre-menstrual Syndrome. Co-sponsored by the Centre for Studies of Affective Disorders and the Psychobiological Processes and Behavioral Medicine Section. Rockville (MD): 1983 Apr: 14-15

Frye GM, Silverman SD. Is it premenstrual syndrome? Keys to focused diagnosis, therapies for multiple symptoms. Postgrad Med 2000 May; 107(5): 151–9

Lampe L. Antidepressants: not just for depression. Aust Prescr 2005 Aug; 28(4): 91–3

Pearlstein TB. Hormones and depression: what are the facts about premenstrual syndrome, menopause, and hormone replacement therapy? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995 Aug; 173(2): 646–53

Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Frischer M, et al. Prescribing patterns in premenstrual syndrome. BMC Womens Health 2002 Jun; 2(4): 1–8

Landen M, Eriksson E. How does premenstrual dysphoric disorder relate to depression and anxiety disorders? Depress Anxiety 2003; 17(3): 122–9

Quah-Smith JI, Tang WM, Russell J. Laser acupuncture for mild to moderate depression in a primary care setting: a randomised controlled trial. Acupunct Med 2005 Sep; 23(3): 103–11

Nielson A, Williams T. Depression in ambulatory medical patients, prevalence by self-report questionnaire and recognition by non-psychiatric physicians. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980; 37: 999–1004

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961 Jun; 4: 561–71

Sheenan-Dare RA, Henderson MJ, Cotterill JA. Anxiety and depression in patients with chronic urticaria and generalised pruritus. Br J Dermatol 1990; 123(6): 769–74

Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: STAI (Form Y). Palo Alto (CA): Consulting Psychologists Press, 1983

Pocock SJ. Clinical trials: a practical approach. Chichester: John Wiley, 1983

Chisholm G, Jung SO, Cumming CE, et al. Premenstrual anxiety and depression: comparison of objective psychological tests with retrospective questionnaire. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1990 Jan; 81(1): 52–7

Halbreich U. The etiology, biology, and evolving pathology of premenstrual syndromes. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003 Aug; 28Suppl. 3: 55–99

Warner P, Bancroft J. Factors related to self-reporting of the pre-menstrual syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 1990 Aug; 157: 249–60

Hartlage SA, Arduino KE. Toward the content validity of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: do anger and irritability more than depressed mood represent treatment-seekers’ experience? Psychol Rep 2002 Feb; 90(1): 189–202

Buss AH, Perry M. The Aggression Questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol 1992 Sep; 63(3): 452–9

Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol 1995 Nov; 51(6): 768–74

Bryant M, Cassidy A, Hill C, et al. Effect of consumption of soy isoflavones on behavioural, somatic and affective symptoms in women with premenstrual syndrome. Br J Nutr 2005 May; 93(5): 731–9

Freeman EW, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ, et al. Differential response to antidepressants in women with premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999 Oct; 56(10): 932–9

FitzGerald SP, Lamont JV, McConnell RI, et al. Development of a high-throughput automated analyzer using biochip array technology. Clin Chem 2005 Jul; 51(7): 1165–76

Hildesheim A, Ryan RL, Rinehart E, et al. Simultaneous measurement of several cytokines using small volumes of biospecimens. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2002 Nov; 11(11): 1477–84

Stevinson C, Ernst E. A pilot study of Hypericum perforatum for the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. BJOG 2000 Jul; 107(7): 870–6

Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL. Essentials of behavioral research: methods and data analysis. 2nd ed. Singapore: McGraw-Hill, 1999

Machin D, Campbell MJ. Statistical tables for the design of clinical trials. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1987

Pearlstein TB, Stone AB, Lund SA, et al. Comparison of fluoxetine, bupropion, and placebo in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997 Aug; 17(4): 261–6

Carlson NR. Foundations of Physiological Psychology. Boston (MA): Allyn and Bacon, 1988

Dantzer R, Wollman E, Vitkovic L, et al. Cytokines and depression: fortuitous or causative association? Mol Psychiatry 1999 Jul; 4(4): 328–32

Smith RS. The macrophage theory of depression. Med Hypotheses 1991 Aug; 35(4): 298–306

Yonkers KA, O’Brien PMS, Eriksson E. Premenstrual syndrome. Lancet 2008 Apr; 371(9619): 1200–10

Nangia M, Syed W, Doraiswamy PM. Efficacy and safety of St. John’s wort for the treatment of major depression. Public Health Nutr 2000; 3(4A): 487–94

Raffa RB. Screen of receptor and uptake-site activity of hypericin component of St. John’s wort reveals sigma receptor binding. Life Sci 1998 Mar; 62(16): PL265–70

Lester NA, Keel PA, Lipson SF. Symptom fluctuation in bulimia nervosa: relation to menstrual-cycle phase and cortisol levels. Psychol Med 2003; 33(1): 51–60

Price WA, Torem MS, DiMarzio LR. Premenstrual exacerbation of bulimia. Psychosomatics 1987; 28: 378–9

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders — Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, version 2.0). New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1995

Evans SM, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Food “cravings” and the acute effects of alprazolam on food intake in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Appetite 1999 Jun; 32(3): 331–49

Facchinetti F, Borella P, Sances G, et al. Oral magnesium successfully relieves premenstrual mood changes. Obstet Gynecol 1991 Aug; 78(2): 177–81

Freeman EW, Stout AL, Endicott J, et al. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome with a carbohydrate-rich beverage. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2002; 77(3): 253–4

De Souza MC, Walker AF, Robinson PA, et al. A synergistic effect of a daily supplementation for 1 month of 200 mg magnesium plus 50 mg vitamin B6 for the relief of anxiety-related premenstrual symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2000 Mar; 9(2): 131–9

Sayegh R, Schiff I, Wurtman J, et al. The effect of a carbohydrate-rich beverage on mood, appetite, and cognitive function in women with premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 1995 Oct; 86 (4 Pt 1): 520–8

Walker AF, De Souza MC, Vickers MF, et al. Magnesium supplementation alleviates premenstrual symptoms of fluid retention. J Womens Health 1998 Nov;7(9): 1157–65

Freeman EW, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ, et al. A double-blind trial of oral progesterone, alprazolam, and placebo in treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome. JAMA 1995 Jul; 274(1): 51–7

Freeman EW, Sondheimer SJ, Sammel MD, et al. A preliminary study of luteal phase versus symptom-onset dosing with escitalopram for premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005 Jun; 66(6): 769–73

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Lichtwer Pharma AG (Berlin, Germany) for the donation of the supplements and the Rosalind Bolton Bequest for funding the PhD studentship of the corresponding author. The Rosalind Bolton Bequest played no role in the production or submission of this manuscript. Thanks are also due to Biss Hartley for assisting Dr Julie Ayres with clinical interviews and to Uma Ekbote and Sarah Field for technical assistance.

No other sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Authors’ contributions: SC, LD, MW and NS designed the study and interpreted the data. SC collected the data. SC and LD analysed the data. SC wrote the paper. LD, MW, NS and NO made suggestions for revisions. NO supervised the hormone and cytokine assays. JA undertook clinical interviews with each participant. JA and NS were the physicians responsible for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Canning, S., Waterman, M., Orsi, N. et al. The Efficacy of Hypericum perforatum (St John’s Wort) for the Treatment of Premenstrual Syndrome. CNS Drugs 24, 207–225 (2010). https://doi.org/10.2165/11530120-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11530120-000000000-00000