Abstract

Background

Osteoporosis is a common cause of disability and death in elderly men and women. Until 2007, Australian Government-subsidized use of oral bisphosphonates, raloxifene and calcitriol (1α,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol) was limited to secondary prevention (requiring x-ray evidence of previous low-trauma fracture). The cost to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme was substantial (164 million Australian dollars in 2005/6).

Objective

To examine the dispensed prescriptions for oral bisphosphonates, raloxifene, calcitriol and two calcium products for the secondary prevention of osteoporosis (after previous low-trauma fracture) in the Australian population.

Methods

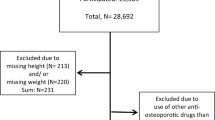

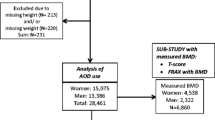

We analysed government data on prescriptions for oral bisphosphonates, raloxifene, calcitriol and two calcium products from 1995 to 2006, and by sex and age from 2002 to 2006. Prescription counts were converted to defined daily doses (DDD)/1000 population/day. This standardized drug utilization method used census population data, and adjusts for the effects of aging in the Australian population.

Results

Total bisphosphonate use increased 460% from 2.19 to 12.26 DDD/1000 population/day between June 2000 and June 2006. The proportion of total bisphosphonate use in June 2006 was 75.1% alendronate, 24.6% risedronate and 0.3% etidronate. Raloxifene use in June 2006 was 1.32 DDD/1000 population/day. The weekly forms of alendronate and risedronate, introduced in 2001 and 2003, respectively, were quickly adopted. Bisphosphonate use peaked at age 80–89 years in females and 85–94 years in males, with 3-fold higher use in females than in males.

Conclusions

Pharmaceutical intervention for osteoporosis in Australia is increasing with most use in the elderly, the population at greatest risk of fracture. However, fracture prevalence in this population is considerably higher than prescribing of effective anti-osteoporosis medications, representing a missed opportunity for the quality use of medicines.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Pharmaceutical Benefits Pricing Authority. Pharmaceutical Benefits Pricing Authority annual report for the year ended 30 June 2008. Canberra ACT): Department of Health and Ageing, 2008

Osteoporosis Australia. The burden of brittle bones: epidemiology, costs and burden of osteoporosis in Australia — 2007. Sydney NSW): Osteoporosis Australia and International Osteoporosis Foundation, 2008

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National health survey 2004-05. Canberra ACT): ABS, 2006

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population by age and sex, Australian states and territories, Jun 2002 to Jun 2007 (Catalogue Number) 3201.0. 2007 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/MF/3201.0 [Accessed 2008 May 4]

Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Australian Statistics on Medicines 2006. Canberra ACT): Department of Health and Ageing, 2008

World Health Organization. World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC index with DDDs, 2005. Oslo: WHO, 2005

Berger JO. Statistical decision theory and Bayesian analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1985

Sterne JA, Davey Smith G. Sifting the evidence: what’s wrong with significance tests? BMJ 2001 Jan 27; 322(7280): 226–31

Reginster JY, Malaise O, Neuprez A, et al. Intermittent bisphosphonate therapy in postmenopausal osteoporosis: progress to date. Drugs Aging 2007; 24(5): 351–9

McGowan B, Bennett K, Barry M, et al. The utilisation and expenditure of medicines for the prophylaxis and treatment of osteoporosis. Ir Med J 2008 Feb; 101(2): 38–41

Rocha O, Lunet N, Costa L, et al. Osteoporosis treatment in Portugal: trends and geographical variation. Acta Med Port 2006 Sep–Oct; 19(5): 373–80

Truter I, Serfontein JH. A survey of the treatment of female patients with osteoporosis using drug utilization consumption parameters. J Clin Pharm Ther 1999 Jun; 24(3): 209–17

Stafford RS, Drieling RL, Hersh AL. National trends in osteoporosis visits and osteoporosis treatment, 1988-2003. Arch Intern Med 2004 Jul 26; 164(14): 1525–30

Nguyen ND, Frost SA, Center JR, et al. Development of prognostic nomograms for individualizing 5-year and 10-year fracture risks. Osteoporos Int 2008 Oct; 19(10): 1431–44

Kamel HK. Male osteoporosis: new trends in diagnosis and therapy. Drugs Aging 2005; 22(9): 741–8

Eisman J, Clapham S, Kehoe L. Osteoporosis prevalence and levels of treatment in primary care: the Australian BoneCare Study. J Bone Miner Res 2004 Dec; 19(12): 1969–75

Kelly AM, Clooney M, Kerr D, et al. When continuity of care breaks down: a systems failure in identification of osteoporosis risk in older patients treated for minimal trauma fractures. Med J Aust 2008 Apr 7; 188(7): 389–91

Perreault S, Dragomir A, Blais L, et al. Population-based study of the effectiveness of bone-specific drugs in reducing the risk of osteoporotic fracture. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2008 Mar; 17(3): 248–59

Perreault S, Dragomir A, Desgagne A, et al. Trends and determinants of antiresorptive drug use for osteoporosis among elderly women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005 Oct; 14(10): 685–95

Center JR, Bliuc D, Nguyen TV, et al. Risk of subsequent fracture after low-trauma fracture in men and women. JAMA 2007 Jan 24; 297(4): 387–94

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Arthritis and osteoporosis in Australia 2008. Arthritis series no. 8. Canberra ACT): AIHW, 2008

Ewald DP, Eisman JA, Ewald BD, et al. Population rates of bone densitometry use in Australia, 2001-2005, by sex and rural versus urban location. Med J Aust 2009 Feb 2; 190(3): 126–8

Main P, Robinson M. Changes in utilisation of hormone replacement therapy in Australia following publication of the findings of the Women’s Health Initiative. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2008 Sep; 17(9): 861–8

Farley JF, Blalock SJ, Cline RR. Effect of the Women’s Health Initiative on prescription anti-osteoporosis medication utilization. Osteoporos Int 2008 Nov; 19(11): 1603–12

Udell JA, Fischer MA, Brookhart MA, et al. Effect of the Women’s Health Initiative on osteoporosis therapy and expenditure in Medicaid. J Bone Miner Res 2006 May; 21(5): 765–71

Pasco JA, Sanders KM, Henry MJ, et al. Calcium intakes among Australian women: Geelong Osteoporosis Study. Aust N Z J Med 2000 Feb; 30(1): 21–7

Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Schedule of pharmaceutical benefits. Canberra ACT): Department of Health and Ageing, 2007

Abbott T. PBS extension to benefit osteoporosis patients. Media release by Minster for Health and Ageing — Tony Abbott MHR. 18 December 2006. ABB162/06. Department of Health and Ageing, 2006 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ministers/publishing.nsf/Content/B11DB3F4D60C73B5CA257247007F8915/$File/abb162.pdf [Accessed 2009 May 22]

Berecki-Gisolf J, Hockey R, Dobson A. Adherence to bisphosphonate treatment by elderly women. Menopause 2008 Sep–Oct; 15(5): 984–90

Roughead EE, Ramsay E, Priess K, et al. Medication adherence, first episode duration, overall duration and time without therapy: the example of bisphosphonates. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2008 Dec 29; 18(1): 69–75

Teede HJ, Jayasuriya IA, Gilfillan CP. Fracture prevention strategies in patients presenting to Australian hospitals with minimal-trauma fractures: a major treatment gap. Intern Med J 2007 Oct; 37(10): 674–9

Acknowledgements

This study was funded from existing salaries. Samantha Hollingworth, Inong Gunanti and Lisa Nissen have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study. Emma Duncan has received speaker fees from Sanofi-Aventis/Procter and Gamble, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis and Servier; has acted as a consultant to Amgen and Merck Sharp & Dohme; and has received travel assistance from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Sanofi-Aventis, Aventis and Servier to attend meetings. The data in these graphs were produced by the DUSC, Pharmaceutical Benefits Branch, Pharmaceutical Benefits Division, Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing. The authors are grateful to Dr Rob Ware for his statistical advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hollingworth, S.A., Gunanti, I., Nissen, L.M. et al. Secondary Prevention of Osteoporosis in Australia. Drugs Aging 27, 255–264 (2010). https://doi.org/10.2165/11318400-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11318400-000000000-00000