Abstract

Objective

To investigate the effect of a heart failure disease management program for patients ≥18 years of age enrolled in a commercial health plan.

Background

Disease management provides a framework for managing the chronic illness of large populations. Evaluating the comparative benefits of disease management program participation remains a central challenge for researchers, clinicians, and administrators. A growing consensus in the field of disease management is that more rigorous methodologies are required to assess program outcomes. However, many heart failure disease management programs have been evaluated by the use of non-experimental designs (pre-/post-methodologies), or matching and stratification methods that have been used with limited success.

Methods

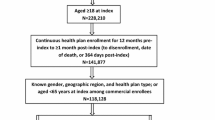

To investigate the program effects of a heart failure care support program, we conducted a matched-cohort study on 521 participants using propensity scores. This methodology constructed matched samples of treated and control pairs for a wide range of observed characteristics and may reduce the bias in estimates of treatment effects to provide a relatively more accurate assessment of program outcomes. Administrative claims provided the source data for evaluating rates of hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and physician office visits. The study also included selected clinical indicators from administrative claims data to estimate the effects of program enrollment.

Results

Participants exhibited significantly fewer cardiac-related inpatient admissions and bed days compared with those for matched cohorts. A greater proportion of participants received cardiography testing and pneumococcal and influenza immunizations compared with matched cohorts. Participants experienced less use of medical services overall, suggesting that there were beneficial effects with monitoring and education for this group.

Conclusions

This study documents the beneficial outcomes of participation in a commercially delivered heart failure care support program. In those cases where controlled randomized clinical trials cannot be performed because of ethical, cost, or feasibility issues, the use of propensity scores provides an alternative for estimating treatment effects based on observational data.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Trends monitoring in chronic care. United States: RWJ, 1997

American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics — 2003 update. Dallas (TX): American Heart Association, 2002

American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics — 2004 update. Dallas (TX): American Heart Association, 2003

Ho KK, Pinsky JL, Kannel WB, et al. The epidemiology of heart failure: the Framingham Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993; 22 (4 Suppl. A): 6A–13A

Eriksson H. Heart failure: a growing public health problem. J Intern Med 1995; 237(2): 135–41

Adams KF, Zannad F. Clinical definition of advanced heart failure. Am Heart J 1998; 135 (6 Pt 2 Suppl): S204–15

Massie BM, Shah NB. Evolving trends in the epidemiologic factors of heart failure: rationale for preventive strategies and comprehensive disease management. Am Heart J 1997; 133(6): 703–12

Ghali JK, Cooper R, Ford E. Trends in hospitalization rates for heart failure in the United States, 1973–1986: evidence for increasing population prevalence. Arch Intern Med 1990; 150(4): 769–73

Graves EJ. National hospital discharge survey: annual summary, 1993. Vital Health Stat 13 1995; 121: 1–63

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cerebrovascular disease mortality and Medicare hospitalization: United States, 1980–1990. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1992; 41(26): 477–80

Simons WR, Haim M, Rizzo J, et al. Effect of improved disease management strategies on hospital length of stay in the treatment of congestive heart failure. Clin Ther 1996; 18(4): 726–46

O’Connell JB, Bristow MR. Economic impact of heart failure in the United States: time for a different approach. J Heart Lung Transplant 1994; 13(4): S107–12

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about heart failure in older adults [online]. Available from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/od/oc/media/fact/f990305.htm [Accessed 2003 Jan 10]

NCQA News. NCQA announces intention to certify disease management programs [online]. Available from URL: http://www.ncqa.org/Pages/communications/news/disease_management.htm [Accessed 2003 Jan 10]

Konstam M, Dracup K, Baker D, et al. Heart failure: evaluation and care of patients with left-ventricular systolic dysfunction. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 11. AHCPR Publication No. 94-0612. Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1994

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of heart failure. Circulation 1995; 92(9): 2764–84

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Major drug class [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/ndc/index.htm [Accessed 2003 Jan 10]

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies of causal effect. Biometrika 1983; 76: 41–55

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. J Am Stat Assoc 1984; 79: 516–24

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am Stat 1985; 39: 33–8

Rubin DB, Thomas N. Matching using estimated propensity scores: relating theory to practice. Biometrics 1996; 52: 249–64

Dehejia RH, Wahba S. Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Rev Econ Stat 2002; 84(1): 151–61

Rich MW. Heart failure in the elderly: strategies to optimize outpatient control and reduce hospitalizations. Am J Geriatr Cardiol 2003; 12(1): 19–27

Young JB, Pratt CM. Hemodynamic and hormonal alterations in patients with heart failure: toward a contemporary definition of heart failure. Semin Nephrol 1994; 14(5): 427–40

Rich M, Vinson JM, Sperry JC, et al. Prevention of readmission in elderly patients with congestive heart failure: results of a prospective, randomized pilot study. J Gen Intern Med 1993; 8(11): 585–90

Ghali JK, Kadakia S, Cooper R, et al. Precipitating factors leading to decompensation of heart failure: traits among urban blacks. Arch Intern Med 1988; 148(9): 2013–6

Gooding J, Jette AM. Hospital readmissions among the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 1985; 33(9): 595–601

Gupta SC. Congestive heart failure in the elderly: the therapeutic challenge of atypical presentations. Postgrad Med 1991; 90(7): 83–7

Riegel B, Carlson B, Kopp Z, et al. Effect of a standardized nurse case-management telephone intervention on resource use in patients with chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(6): 705–12

Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, et al. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1995; 333(18): 1190–5

Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning for hospitalized elderly: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1994; 120(12): 999–1006

Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 1999; 281(7): 613–20

Knox D, Mischke L. Implementing a congestive heart failure disease management program to decrease length of stay and cost. J Cardiovasc Nurs 1999; 14(1): 55–74

McAlister FA, Lawson FM, Teo KK, et al. A systematic review of randomized trials of disease management programs in heart failure. Am J Med 2001; 110(5): 378–84

Philbin EF, Rocco TA, Lindenmuth NW, et al. The results of a randomized trial of a quality improvement intervention in the care of patients with heart failure. Am J Med 2000; 109(6): 501–3

Riegel B, Carlson B, Glaser D, et al. Which patients with heart failure respond best to multidisciplinary disease management? J Card Fail 2000; 6(4): 290–9

Frigoletto FD, Lieberman E, Lang JM, et al. A clinical trial of active management of labor. N Engl J Med 1995; 333(12): 745–50

Gunn PA, Thamilarasan M, Watnabe J, et al. Aspirin use and all-cause mortality among patients being evaluated for known or suspected coronary artery disease: a propensity analysis. JAMA 2001; 286(10): 1187–94

Peterson JG, Tool EJ, Roe MT, et al. Prognostic importance of concomitant heparin with eptifibatide in acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol 2001; 87(5): 532–6

Connors AF, Speroff T, Dawson NV, et al. The effectiveness of right heart catheterization in the initial care of critically ill patients. JAMA 1996; 276(11): 889–97

Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Williams, 1988: 138

Foster ME. Propensity score matching: an illustrative analysis of dose response. Med Care 2003; 41(10): 1183–92

Berg GD, Johnson A, Fleegler E. Clinical and utilization outcomes for a pediatric and adolescent telephonic asthma care support program. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2003; 11(7): 737–43

Berg GD, Wadhwa S, Johnson A. A matched-cohort study of health services utilization and financial outcomes for a heart failure disease-management program in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52: 1–7

Riegel B, Carlson B, Glaser D, et al. Which patients with heart failure respond best to multidisciplinary disease management? J Card Fail 2000; 6(4): 290–9

Whellan DJ, Gaulden L, Gattis WA, et al. The benefit of implementing a heart failure disease management program. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161(18): 2223–8

Hershberger RE, Ni H, Nauman DJ, et al. Prospective evaluation of an outpatient heart failure management program. J Card Fail 2001; 7(1): 64–74

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Kim Byrwa, Director of Health Promotions/Disease Management at Anthem, who coordinated the acquisition of data, established meeting schedules, and managed Anthem staff review and critique of the manuscript. Contact information: www.KimByrwa@anthem.com.

Alan Johnson, Gregory Berg, and Edward Fleeger are employees of McKesson Corporation in Broomfield, Colorado, USA, whose disease management program is being evaluated in the study. Jeanne Lehn was an employee of Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield in Mason, Ohio, USA, at the time of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, A., Berg, G., Fleegler, E. et al. Clinical and Utilization Outcomes for a Heart Failure Care Support Program. Dis-Manage-Health-Outcomes 13, 327–335 (2005). https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200513050-00005

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200513050-00005