Abstract

Introduction

A new combination vaccine, diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis (DTaP)-hepatitis B (HepB)-inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) [DTaP-HepB-IPV], recently became available for use in the US primary infant-vaccination series. Our objectives were to estimate its effects on immunization-coverage rates, vaccination activities, and health-system costs in US dollars (2003 values).

Methods

A model was developed and applied to medical records of 775 children born in mid-2001 who received primary care at 32 private pediatrics centers. DTaP-HepB-IPV use was predicted by applying decision rules to selectively substitute it for component vaccines, in compliance with the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ minimum age and time interval criteria. The model considered effects of DTaP-HepB-IPV on use of HepB at age <6 weeks, and HepB, HepB-Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), Hib, DTaP, and IPV at age 6 weeks to 2 years.

Results

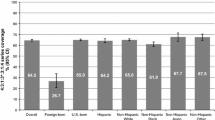

At 2 years of age, DTaP-HepB-IPV would increase the proportion of children receiving three or more doses of DTaP (95.6% vs 96.4%; p = 0.02), HepB (91.7% vs 95.2%; p < 0.001), IPV (90.7% vs 96.3%; p < 0.001), and each of these vaccines (86.2% vs 94.6%; p < 0.001), compared with those receiving each component in singular or combination vaccinations other than DTaP-HepB-IPV. Coverage rates would also be increased for recommended doses of all three component vaccines at ages 1 and 1½ years. At 2 years of age, the use of DTaP-HepB-IPV would also reduce the number of injections (17.3 vs 14.6; p < 0.001), vaccination visits (6.8 vs 6.6; p = 0.006), and administration costs ($US240 vs $US203; p = 0.004), compared with those receiving each component in singular or combination vaccinations other than DTaP-HepB-IPV.

Conclusion

DTaP-HepB-IPV use is estimated to improve immunization coverage rates while reducing the number of vaccine injections, vaccination visits, and costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The use of trade names is for product identification purposes only and does not imply endorsement.

References

Offit PA, Quarles J, Gerber MA, et al. Addressing parents’ concerns: do multiple vaccines overwhelm or weaken the infant’s immune system? Pediatrics 2002; 109: 124–9

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notice to readers: FDA licensure of diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis adsorbed, hepatitis B (recombinant), and poliovirus vaccine combined, (PEDIARIX™) for use in infants. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003; 52(10): 203–4

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended childhood and adolescent immunization schedule. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003; 52: Q1–4

Cooper A, Yusuf H, Rodewald L, et al. Attitudes, practices, and preferences of pediatricians regarding initiation of hepatitis B immunization at birth. Pediatrics 2001; 108: E98

Meyerhoff AS, Weniger BG, Jacobs RJ. Economic value to parents of reducing the pain and emotional distress of childhood vaccine injections. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2001; 20: S57–62

Lieu TA, Black SB, Ray T, et al. The hidden costs of infant vaccination. Vaccine 2001; 19: 33–41

Ad Hoc Working Group for the Development of Standards for Pediatric Practices. Standards for pediatric immunization practices. JAMA 1993; 269: 1817–22

Melman ST, Chawla T, Kaplan JM, et al. Multiple immunizations. Arch Fam Med 1994; 3: 615–8

Madlon-Kay D, Harper P. Too many shots? Parent, nurse and physician attitudes toward multiple simultaneous childhood vaccinations. Arch Fam Med 1994; 3: 610–3

Zimmerman RK, Bradford BJ, Janosky JE, et al. Barriers to measles and pertussis immunization: the knowledge and attitudes of Pennsylvania primary care physicians. Am J Prev Med 1997; 13: 89–97

Freed GL, Bordley WC, Clark SJ, et al. Reactions of pediatricians to a new Centers for Disease Control recommendation for universal immunization of infants with hepatitis B vaccine. Pediatrics 1993; 91: 699–702

Woodin KA, Rodewald LE, Humiston SG, et al. Physician and parent opinions: are children becoming pincushions from immunizations? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995; 149: 845–9

Meyerhoff AS, Jacobs RJ. Do too many shots due lead to missed vaccination opportunities? Prev Med 2005; 41: 540–44

Lieu TA, Shinefield HR, Ray P, et al. Would better adherence to guidelines improve childhood immunization rates? Pediatrics 1996; 98: 1062–8

Lieu TA, Davis RL, Capra AM, et al. Variation in clinician recommendations for multiple injections during adoption of inactivated polio vaccine. Pediatrics 2001; 107: e49

Sabnis SS, Pomeranz AJ, Lye PS, et al. Do missed opportunities stay missed? A 6-month follow up of missed vaccine opportunities in Inner City Milwaukee children. Pediatrics 1998; 10: 1–4

Taylor JA, Darden PM, Brooks DA, et al. Practitioner policies and beliefs and practice immunization rates: a study from pediatric research in office settings and the National Medical Association. Pediatrics 2002; 109: 294–300

Tanaka M, Vitek CR, Pascual FB, et al. Trends in pertussis among infants in the United States, 1980–1999. JAMA 2003; 290: 2968–75

Weinstein MC, Fineberg HV. Clinical decision analysis. Philadelphia (PA): WB Saunders Company, 1980

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines for Children Program. VFC program data [online]. Available from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nip/vfc/data.htm [Accessed 2000 Mar 21]

Fleming GV. Vaccine administration fee survey. In: Child health care update. Elk Grove (IL): The American Academy of Pediatrics, 1995; 11–6

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine price list [online]. Available from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nip/vfc/cdc_vac_price_list.htm. [Accessed 2003 Mar 19]

Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. New York: Wiley & Sons, 1981

Plotkin SA, Murdin A, Vidor E. Inactivated polio vaccine. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, editors. Vaccines. Philadelphia (PA): WB Saunders Company, 1999

Mahoney FJ, Kane M. Hepatitis B vaccine. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, editors. Vaccines. Philadelphia (PA): WB Saunders Company, 1999

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated vaccination coverage with individual vaccines by state and immunization action plan area: US, National Immunization Survey, Q1/2002–Q4/2002 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nip/coverage/NIS/01.htm [Accessed 2003 Oct 14]

US Census Bureau. Statistical abstract of the United States: 2000. 120th ed. Women who have had a child in the last year by age and labor force status: 1980 to 1998. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau, 2000

Zhou W, Pool V, Iskander JK. Surveillance for safety after immunization: vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS): United States, 1991–2001. MMWR Surveill Summ 2003; 52(1): 1–24

Pediarix™ diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis adsorbed, hepatitis B (Recombinant) and inactivated poliovirus vaccine combined [prescribing information]. Rixensart, Belgium: GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, 2003 Aug

Meyerhoff AS, Weniger BJ, Jacobs RJ. Economic value to parents of reducing the pain and emotional distress of childhood vaccine injections. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2001; 20: (11 Suppl.): S57–62

Haddix AC, Shaffer PA. Cost-effectiveness analysis. In: Haddix AC, Teutsch SM, Shaffer PA, et al., editors. Prevention effectiveness. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996

Smith PJ, Chu SY, Barker LE. Children who received no vaccine doses: who are they and where do they live? Pediatrics 2004; 114: 187–95

Yusuf HR, Daniels D, Smith P, et al. Association between administration of hepatitis B vaccine at birth and completion of the hepatitis B and 4: 3: 1: 3 vaccine series. JAMA 2000; 284: 978–83

Thomas AR, Fiore AE, Corwith HL, et al. Hepatitis B vaccine coverage among infants born to women without prenatal screening for hepatitis B virus infection: effects of the Joint Statement on Thimerosal Vaccines. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004; 23: 313–8

Geber A. April 9, 2002. Daptacel clinical review. Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/cber/review/dtapave051402r.pdf [Accessed 2004 Oct 22]

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored through an unrestricted research grant from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). GSK exercised no control or influence in either the study’s methods or this manuscript.

Allen Meyerhoff and R. Jake Jacobs have each received honoraria from GSK for meeting attendance and David Greenberg has received honoraria from GSK for meeting attendance and investigator fees for participation in GSK clinical trials. No author owns or has owned any GSK stock.

We thank Tracey Craddock for her work in organizing participating centers and their patients, Kurt Luedke for developing the software to implement the model, and GSK for their unrestricted research grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meyerhoff, A.S., Greenberg, D.P. & Jake Jacobs, R. Predicted Effects of a New Combination Vaccine on Childhood Immunization Coverage Rates and Vaccination Activities. Dis-Manage-Health-Outcomes 13, 317–326 (2005). https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200513050-00004

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200513050-00004