Abstract

Depression is under-detected, but is treatable and relapses can be prevented. Living with depression, whether acute or chronic, has consequences for quality of life, premature end of life, and productive life. Thoughtful and strategic quality improvement (QI) programs offer one avenue for improving the treatment of depression. Part I of this two-part series addresses improving the treatment of depression and employing disease management as a strategy to accomplish that aim. This article, part II, provides an overview of other QI initiatives that demonstrated treatment effectiveness for depression, including several used in managed care practice.

Currently, the majority of QI programs for depression target adult patients; therefore, there are future challenges ahead as managed care attempts to address the needs of special populations, such as adolescents and older adults. Public education, professional education, and population-based interventions are also considerations as part of successful treatment. Although consumer-based interventions are typically more expensive, they may ultimately yield the best results for improving depression care for the consumer and payors based on available research. The success of a consumer-centric approach is highly reliant on the person’s engagement with QI programs, the treating clinician’s appreciation and support of such depression programs, and managed care’s response to solving quality problems using continuous monitoring, evaluation, feedback, system enhancements, and training. Models of collaboration between consumers and medical and behavioral health systems offer the most promising approaches to care improvements for patients with depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

National Center for Health Statistics. Health United States, 2002 with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville (MD): Centers for Disease Control, 2002

Oss ME, Jardine E, Pesare MJ. OPEN MINDS yearbook of managed behavioral health & employee assistance program market share in the United States, 2002–2003. Gettysburg (PA): Behavioral Health Industry News, 2003

US Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: a report of the surgeon general. Rockville (MD): US Department of Mental Health, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental, 1999

Leatherman S, McCarthy D. Quality of health care in the United States: a chartbook. New York: Commonwealth Fund, 2002 Apr

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999 Dec; 56(12): 1109–15

Simon GE, VonKorff M, Barlow W. Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995 Oct; 52(10): 850–6

Adams K, Corrigan J, editors. Priority areas for national action: transforming health care quality. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2003

National Committee for Quality Assurance. NCQA Memorandum: 2003 MCO Accreditation — Benchmarks and Thresholds, 2003 Feb 7

Shortell SM, O’Brien JL, Carman JM, et al. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement/total quality management. Health Serv Res 1995; 30(2): 377–401

Brody DS. Improving the management of depression in primary care: recent accomplishments and ongoing challenges. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2003; 11(1): 21–31

Delgado PL. Approaches to the enhancement of patient adherence to antidepressant medication treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61 Suppl. 2: 6–9

Frank E. Enhancing patient outcomes: treatment adherence. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 58 Suppl. 1: 11–4

Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000; 283(2): 212–20

Aubert RE, Fulop G, Xia F, et al. Evaluation of a depression health management program to improve outcomes in first or recurrent episode depression. Am J Manag Care 2003; 9(5): 374–80

Elliot J, Egherman L. Improving antidepressant medication management and medication adherence for adults. National Association for Healthcare Quality 28th Annual Educational Conference; 2003 Sep 6–9; Phoenix (AZ)

Lin EH, VonKorff M, Russo J, et al. Can depression treatment in primary care reduce disability? A stepped care approach. Arch Fam Med 2000; 9(10): 1052–8

Mischoulon D, McColl-Vuolo R, Howarth S. Management of major depression in the primary care setting. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics 2001; 70(2): 103–7

Peveler R, George C, Kinmouth AL, et al. Effect of antidepressant drug counseling and information leaflets on adherence to drug treatment in primary care: randomized controlled trial. BMJ 1999; 319(7210): 612–5

Roberts K, Cockerham TR, Waugh WJ. An innovative approach to managing depression: focus on HEDIS standards. J Healthcare Qual 2002 Nov–Dec; 24(6): 11–7

Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, et al. Improving depression outcomes in community primary care practice: a randomized trial of the QuEST intervention. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16(3): 143–9

Un\:utzer J, Rubenstein L, Katon W. Two-year effects of quality improvement programs on medication management for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001 Oct; 58(10): 935–42

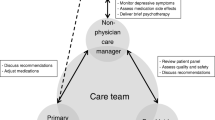

Rubenstein LV, Parker L, Meredith LS. Understanding team-based quality improvement for depression in primary care. Health Serv Res 2002 Aug; 37(4): 1009–29

Schoenbaum M, Uniitzer J, Sherbourne CD, et al. Cost-effectiveness of practice-initiated quality improvement for depression. JAMA 2001; 286(11): 1325–30

Simon GE, VonKorff M, Rugger C, et al. Randomised trial of monitoring, feedback, and management of care by telephone to improve treatment of depression in primary care. BMJ 2000; 320(7234): 550–4

Tai-Seale M, Croghan TW, Obenchain R. Determinants of antidepressant treatment compliance: implications for policy. Med Care Res Rev 2000; 57(4): 491–512

Tutty S, Simon G, Ludman E. Telephone counseling as an adjunct to antidepressant treatment in the primary care system: a pilot study. Eff Clin Pract 2000; 3(4): 170–8

Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Duan N, et al. Long-term effectiveness of disseminating quality improvement for depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58(7): 696–703

Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression: results of a group-level randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61(4): 378–86

Sherman SE, Chapman A, Garcia D, et al. Improving recognition of depression in primary care: a study of evidence-based quality improvement. Jt Comm J Qual Saf 2004; 30(2): 80–8

Broday H, Draper BM, Millar J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of different models of care for nursing home residents with dementia complicated by depression or psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64(1): 63–72

Solberg LI, Fischer LR, Wei F, et al. A CQI intervention to change the care of depression: a controlled study. Eff Clin Pract 2003; 4(6): 239–49

Brown JB, Shye D, McFarland BH, et al. Controlled trails of CQI and academic detailing to implement a clinical practice guideline for depression. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 2000 Jan; 26(1): 39–54

Capoccia KL, Boudreau DM, Blough DK, et al. Randomized trial of pharmacist interventions to improve depression care and outcomes in primary care. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2004; 61(4): 364–32

Finley PR, Rens HR, Pont JT, et al. Impact of a collaborative care model on depression in a primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy 2003 Sep; 23(9): 1175–85

Brook O, van Hout H, Nieuwenhuyse H, et al. Impact of coaching by community pharmacists on drug attitude of depressive primary care patients and acceptability to patiens; a randomized controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2003; 139(1): 1–9

Wasson J, Gaudette C, Whaley F, et al. Telephone care as a substitute for routine clinic follow-up. JAMA 1992 Apr; 267(13): 1788–93

Datto CJ, Thompson R, Horowitz D, et al. The pilot study of a telephone disease management program for depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003; 25(3): 169–77

Hunkeler EM, Meresman JF, Hargreaves WA, et al. Efficacy or nurse telehealth care and peer support in augmenting treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med 2000; 9(8): 700–8

Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF. Delivering interventions for depression by using the internet: randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2004; 328(7434): 265

Clarke G, Reid E, Eubanks D, et al. Overcoming depression on the Internet (ODIN): a randomized controlled trial of an Internet depression skills intervention program. J Med Internet Res 2002; 4(3): E14

Von Korff M, Katon W, Rutter C, et al. Effect on disability outcomes of a depression relapse prevention program. Psychosom Med 2004; 65(6): 938–43

Jorm AF, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, et al. Providing information about the effectiveness of treatment options to depressed people in the community: a randomized controlled trial of effects on mental health literacy, help-seeking and symptoms. Psychol Med 2003 Aug; 33(6): 1071–9

Patten SB. Prevention of depressive symptoms through the use of distance technologies. Psychiatr Serv 2003; 54(3): 396–8

Mundt JC, Glarke GN, Burroughs D, et al. Effectiveness of antidepressant pharmacotherapy: the impact of medication compliance and patient education. Depress Anxiety 2001; 13(1): 1–10

Jacob KS, Bhugra D, Mann AH. A randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention for depression among Asian women in primary care in the United Kingdom. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2002; 48(2): 139–48

Sherill JT, Frank E, Geary M, et al. Psychoeducational workshops for elderly patients with recurrent major depression and their families. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48(1): 7–81

Mahoney DF, Tarlow BJ, Jones RN. Effects of an automated telephone support system on caregiver burden and anxiety: findings from the REACH for TLC intervention study. Gerontologist 2003 Aug; 43(4): 556–67

Eisdorfer C, Czaja SJ, Loewenstein DA, et al. The effect of a family therapy and technology-based intervention on caregiver depression. Gerontologist 2003 Aug; 43(4): 521–31

Greist JH, Osgood-Hynes DJ, Baer L, et al. Technology-based advances in the management of depression: focus on the COPE™ program. Dis Manag Health Outcomes 2000; 7: 193–200

Keystone Health Plan Central. Recruitment flyer. Camp Hill (PA): Keystone Health Plan Central, 2003

Gilbody SD, Whitty P, Grimshaw J, et al. Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care: a systematic review. JAMA 2003; 289(23): 3145–51

Fihn SD, McDonell MB, Diehr P, et al. Effects of sustained audit/feedback on self-reported health status of primary care patients. Am J Med 2004; 116(4): 241–8

Rollman BL, Hanusa BH, Lowe HJ, et al. A randomized trial using computerized decision support to improve treatment of major depression in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2002; 17(7): 493–501

Worrall G, Angel J, Chaulk P, et al. Effectiveness of an educational strategy to improve family physicians’ detection and management of depression: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 1999; 161(1): 37–40

Gask L, Dowrick C, Dixon C, et al. A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention for GPs in the assessment and management of depression. Psychol Med 2004; 34(1): 63–72

Baker R, Reddish S, Robertson N, et al. Randomised controlled trial of tailored strategies to implement guidelines for the management of patients with depression in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2001; 51(470): 737–41

Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Duan N, et al. Long-term effectiveness of disseminating quality improvement for depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001 Jul; 58(7): 696–703

Stimmel GL. Maximizing treatment outcome in depression: strategies to overcome social stigma and noncompliance. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2001; 9: 179–86

Acknowledgments

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beaudin, C.L., Kramer, T.L. Evaluation and Treatment of Depression in Managed Care (Part II). Dis-Manage-Health-Outcomes 13, 307–316 (2005). https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200513050-00003

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200513050-00003