Abstract

Depression is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide, contributing to high medical expenditures, poor clinical outcomes, low productivity, and compromised quality of life. Efficacious treatments are available for the treatment of depression across a broad age range (children/adolescents to elderly). Care management initiatives that include these promising interventions ameliorate the impact of the disorder among patients receiving mental health services in primary care and behavioral healthcare settings. Part I of this two-part article series provides the reader with an overview of issues related to improving the treatment of depression. The approaches used to treat depression and strategies employed to evaluate treatment success are critical. Disease management is one strategy used for improving depression treatment that benefits the consumer and yields positive results for providers and payors.

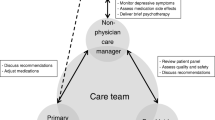

The most effective strategies are those with multiple components, including patient education, coordination of care between primary care and mental health specialists, and ongoing evaluation and feedback. Although the benefits of such interventions are profound in producing improvements in depressive symptoms, social and emotional functioning, and overall satisfaction, there have been few healthcare systems that have successfully integrated such programs into routine care. Despite indirect advantages to providers and payors, the costs of implementing such programs may present a larger barrier to system-wide adoption of disease management for depression. Certainly, the potential for healthcare cost reductions needs to be systematically examined, particularly the extent to which certain patient groups (the most interesting being those with the highest healthcare costs or catastrophic outcomes of their depression) will benefit from disease management programs. Subpopulations (e.g. children, adolescent and older adults) have associated extant barriers that impede progress with implementing disease management support services and programs.

Part II provides an overview of quality improvement strategies demonstrated to be effective in improving depression treatment and discusses examples of programs implemented in various care settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Murray CJ, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from disease, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Boston (MA): Harvard School of Public Health on behalf of the World Health Organization and the World Bank, 1996

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Dernier O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003 Jun 18; 289(23): 3095–105

National Institute of Mental Health. The numbers count: mental disorders in America [online]. Available from URL: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/numbers.cfm [Accessed 2004 July 12]

Miniño AM, Arias E, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Smith BL. Deaths: final data for 2000. National Vital Statistics Reports, 50 (15). Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics, 2002

Lin EH, Katon WJ, Von Korff M, et al. Relapse of depression in primary care: rate and clinical predictors. Arch Fam Med 1998; 7: 443–9

Kramer TL, Daniels AS, Zieman GL, et al. Psychiatric practice variations in the diagnosis and treatment of major depression. Psychiatr Serv 2000; 51(3): 336–40

Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC. Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States: prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. J Gen Intern Med 2000; 15: 284–92

National Center for Health Statistics. Health United States, 2002 with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics, 2002

Oss ME, Jardine E, Pesare MJ. OPEN MINDS yearbook of managed behavioral health & employee assistance program market share in the United States, 2002–2003. (PA): Behavioral Health Industry News, 2002

Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64(12): 1465–75

Simon GE, VonKorff M, Barlow W. Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depresssion. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995 Oct; 52(10): 850–6

Kupfer DJ, Frank E. Comorbidity in depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2003; 108 Suppl. 418: 57–60

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Depression in primary care: vol. II. Treatment of major depression clinical practice guideline, No. 5. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1993. AHCPR Publication No. 93-0551

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37 Suppl. 10: 63S–83S

Armstrong EP. Antidepressant treatment patterns and success rates in a managed care organization. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2003; 11(3): 173–80

Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC. Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States: prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. J Gen Intern Med 2000 May; 15: 284–92

Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001 Jan; 58: 55–61

Wu P, Hoven CW, Cohen P, et al. Factors associated with use of mental health services for depression by children and adolescents. Psychiatr Serv 2001 Feb; 52: 189–95

Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50: 85–94

Fortney J, Rost K, Zhang M. A joint choice model of the decision to seek depression treatment and choice of provider sector. Med Care 1998; 36: 307–20

Charbonneau A, Rosen AK, Ash AS, et al. Measuring the quality of depression care in a large integrated health system. Med Care 2003; 41(5): 669–80

Kramer TL, Daniels AS, Zieman GL, et al. Psychiatric practice variations in the diagnosis and treatment of major depression. Psychiatr Serv 2000; 51(3): 336–40

Simon GE, VonKorff M. Recognition, management, and outcomes of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med 1995; 4: 99–105

Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, et al. The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Serve Res 2001; 36 (6 Pt 1): 987–1007

Mischoulon D, McColl-Vuolo R, Howarth S, et al. Management of major depression in the primary care setting. Psychother Psychosom 2001 Mar–Apr; 70(20): 103–7

Book J. Diagnosis of anxiety and depression: point-of-system entry — a managed behavioral health organization perspective. Managed Care Suppl 2004 Feb; 13(2): 20–2

Woolf SH. Practice guidelines: a new reality in medicine, III. Impact on patient care. Arch Intern Med 1993; 153(26): 2646–55

Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, et al. Getting research findings into practice: closing the gap between research and practice. An overview of systemic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. BMJ 1998; 317: 465–8

Brody DS. Improving the management of depression in primary care: recent accomplishments and ongoing challenges. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2003; 11(1): 21–31

Lin EH, Simon GE, Katzelnick DJ, et al. Does physician education on depression management improve treatment in primary care? J Gen Intern Med 2001 Sep; 16(9): 614–9

Thompson C, Kinmonth AL, Stevens L, et al. Effects of a clinical-practice guideline and practice-based education on detection and outcome of depression in primary care: Hampshire Depression Project randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000 Jan 15; 355(9199): 185–91

Rubenstein LV, Parker LE, Meredith LS, et al. Understanding team-based quality improvement for depression in primary care. Health Serv Res 2002; 37(4): 1009–29

Badamgarav E, Weingarten SR, Henning JM, et al. Effectiveness of disease management programs in depression: a systematic review. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160: 2080–90

Brody DS. Improving the management of depression in primary care: recent accomplishments and ongoing challenges. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2003; 11(1): 21–31

Gilbody SM, Whitty PA, Grimshaw JG, et al. Educational and organisational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care. JAMA 2003; 289: 3145–51

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q 1996; 74(4): 511–43

Wagner EH. Managed care and chronic illness: health services research needs. Health Serv Res 1997 Dec; 32(5): 702–14

Hunkeler EM, Meresman JF, Hargreaves WA, et al. Efficacy of nurse telehealth care and peer support in augmenting treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med 2000 Aug; 9: 700–8

Simon GE, VonKorff M, Rutter C, et al. Randomised trial of monitoring, feedback, and management of care by telephone to improve treatment of depression in primary care. BMJ 2000; 320: 550–4

Tutty S, Simon G, Ludman E. Telephone counseling as an adjunct to antidepressant treatment in the primary care system: a pilot study. Eff Clin Pract 2000; 4: 170–8

Disease Management Association of America. Definition of disease management [online]. Available from URL: http://www.dmaa.org/definition.html [Accessed 2004 Jul 15]

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 1995; 273(13): 1026–31

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve depression treatment guidelines. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58 Suppl. 1: 20–3

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56(12): 1109–15

Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, et al. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist: a measure of primary symptom dimensions. In: Pichot P, editor. Psychological measurements in psychopharmacology: problems in pharmacopsychiatry. Basel: Kargerman, 1974: 79–110

Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, et al. Improving depression outcomes in community primary care practice: a randomized trial of the QuEST intervention. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 143–9

Myers JK, Weissman MM. Use of a self-report symptom scale to detect depression in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry 1980; 137: 1081–4

Aubert RE, Fulop G, Xia F, et al. Evaluation of a depression health management program to improve outcomes in first or recurrent episode depression. Am J Manag Care 2003; 9: 374–80

Peveler R, George C, Kinmonth AL, et al. Effect of antidepressant drug counseling and information leaflets on adherence to drug treatment in primary care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 1999 Sep; 319: 612–9

Finley PR, Rens HR, Pont JT, et al. Impact of a collaborative care model on depression in a primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy 2003 Sep; 23(9): 1175–85

Pyne JM, Rost KM, Zhang M, et al. The cost-effectiveness of a primary care depression intervention. J Gen Intern Med 2003; 18(6): 432–41

Von Korff M, Katon W, Bush T, et al. Treatment costs, cost offset and cost-effectiveness of collaborative management of depression. Psychosom Med 1998; 60: 143–9

HEDIS. The health plan employer data and information set [online]. Available from URL: http://www.ncqa.org/Communications/Publications/index.htm. [Accessed 2005 Jun 3]

Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson D, et al. Childhood and adolescent depression: a review of the past 10 years, Part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35: 1427–39

Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53: 339–48

Emslie GJ, Rush AJ, Weinberg WA, et al. Recurrence of major depressive disorder in hospitalized children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36(6): 785–92

Kovacs M. Presentation and course of major depressive disorder during childhood and later years of the life span. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35(6): 705–15

Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, et al. Major depression in community adolescents: age at onset episode duration and time to recurrence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33: 809–18

Robins LN, McEvoy L. Conduct problems as predictors of substance abuse. In: Robins LN, Ruths M, editors. Straight and devious pathways from childhood to adulthood. Cambridge (England): University Press, 1990: 182–204

Martin G, Rozanes P, Pearce C, et al. Adolescent suicide, depression, and family dysfunction. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 92(5): 336–44

Weissman MM, Wok S, Goldstein RB, et al. Depressed adolescents grown up. JAMA 1999; 281(18): 1707–13

US Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: a report of the Surgeon General — executive summary. Rockville (MD): US DHHS, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, NIH & NIMH, 1999

Kramer T, Garralda ME. Psychiatric disorders in adolescents in primary care. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173: 508–13

Chang G, Warner V, Weissman JJ. Physicians’ recognition of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. Am J Dis Child 1988; 142: 736–9

Halpern-Felsher BL, Ozer EM, Millstein SG, et al. Preventive services in a health maintenance organization: how well do pediatricians screen and educate adolescent patients? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000 Feb; 154(2): 173–9

Bartlett JA, Schleifer SJ, Johnson RL, et al. Depression in inner city adolescents attending an adolescent medicine clinic. J Adolesc Health 1991; 12: 316–8

Klein JD, McNulty M, Flatau CN. Adolescents’ access to care: teenagers’ self-reported use of services and perceived access to confidential care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1998; 152(7): 676–82

Asarnow JR, Jaycox LH, Anderson M. Depression among youth in primary care models for delivering mental health services. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2002; 11: 477–97

Zuckerbrot R. Adolescent depression in primary care: to screen or not to screen? Report on Emotional and Behavioral Disorders in Youth, 2003 Spring

Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1977; 1: 385–401

Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Core Version 2.1 interviewer’s manual. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1997

Clarke G, DeBar LL, Ludman E, et al. STEADY project intervention manual and workbook: collaborative care, cognitive behavioral program for depressed youth. Portland (OR): Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, 2000

Clarke GN, DeBar LL, Lynch F, et al. A randomized effectiveness trial of brief cognitive-behavioral therapy for depressed adolescents receiving anti-depressant medication [poster]. NCDEU (New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit) Annual Meeting sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health. Kaiser Permanente’s Center for Health Research; 2002 Jun 10–13; Boca Raton (FL).

Hamilton M. Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000

Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Simon G, et al. Depressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older: a 4-year prospective study. JAMA 1997 May 28; 277(20): 1618–23

Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Rosenheck RA. Depressive symptoms and health costs in older medical patients. Am J Psychiatry 1999 Mar; 156(3): 477–9

Luber MP, Meyers BS, Williams-Russo PG, et al. Depression and service utilization in elderly primary care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001 Spring; 9(2): 169–76

Bula CJ, Wietlisbach V, Burnand B, et al. Depressive symptoms as a predictor of 6-month outcomes and services utilization in elderly medical inpatients. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161: 2609–15

Barry KL, Fleming MF, Manwell LB, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with current and lifetime depression in older adult primary care patients. Fam Med 1998; 30(5): 366–71

Williams SJ, Seidman RL, Drew JA, et al. Identifying depressive symptoms among elderly Medicare HMO enrollees. HMO Pract 1995 Dec; 9(4): 168–73

Harman JS, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, et al. The effect of patient and visit characteristics on diagnosis of depression in primary care [abstract]. J Fam Pract 2001; 50(12): 1068

Unutzer J, Simon G, Belin TR, et al. Care for depression in HMO patients aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000 Aug; 48(8): 871–8

Williams JW, Barrett J, Oxman T, et al. Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: a randomized controlled trial in older adults. JAMA 2000 Sep 27; 284(12): 1519–26

Callahan CM, Dittus RS, Tierney WM. Primary care physicians’ medical decision making for late-life depression. J Gen Intern Med 1996 Apr; 11: 218–25

Whooley MA, Stone B, Soghikian K. Randomized trial of case-findings for depression in elderly primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2000 May; 15: 293–300

Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, et al. The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID): history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49: 624–9

Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, Felker B, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care depression treatment in Veterans’ Affairs primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2003 Jan; 18(1): 9–16

Speer DC, Schneider MG. Mental health needs of older adults and primary care: opportunity for interdisciplinary geriatric team practice. Clin Psychol Sci Prac 2003 Spring; 10(1): 85–101

Wells KB, Golding JM, Burnam MA. Chronic medical conditions in a sample of the general population with anxiety, affective, and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146(11): 1440–6

Kramer TL, Booth BM, Han X, et al. Service utilization and outcomes in medically ill veterans with posttraumatic stress and depressive disorders. J Trauma Stress 2003 Jun; 16(3): 211–9

Grippo AJ, Johnson AK. Biological mechanisms in the relationship between depression and heart disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2002; 26(8): 941–62

Abramson J, Berger A, Krumholz HM, et al. Depression and risk of heart failure among older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Arch Intern Med 2001 Jul 23; 161(14): 1725–30

Jonas BS, Franks P, Ingram DD. Are symptoms of anxiety and depression risk factors for hypertension? Longitudinal evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Arch Fam Med 1997 Jan–Feb; 6(1): 43–9

Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, et al. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2001 Jun; 24(6): 1069–78

Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med 2000 Nov 27; 160(21): 3278–85

Gavard JA, Lustman PJ, Clouse RE. Prevalence of depression in adults with diabetes: an epidemiological evaluation. Diabetes Care 1993 Aug; 16(8): 1167–78

Eaton WW, Armenian H, Gallo J, et al. Depression and risk for onset of type II diabetes: a prospective population-based study. Diabetes Care 1996 Oct; 19(10): 1097–102

Hanninen JA, Takala JK, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi SM. Depression in subjects with type 2 diabetes: predictive factors and relation to quality of life. Diabetes Care 1999; 22: 997–8

Gary TL, Crum RM, Cooper-Patrick L, et al. Depressive symptoms and metabolic control in African-Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2000; 23: 23–9

Egede LE, Zheng D, Simpson K. Comorbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002; 25(3): 464–70

Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, et al. Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care 2000 Jul; 23(7): 934–42

Piette JD, Richardson C, Valenstein M. Addressing the needs of patients with multiple chronic illnesses: the case of diabetes and depression. Am J Managed Care 2004; 10 (2 Pt 2): 152–62

Bunker SJ, Colquhoun DM, Esler MD, et al. “Stress” and coronary heart disease: psychosocial risk factors. Med J Aust 2003; 178: 272–6

Shiotani I, Sato H, Kinjo K, et al. Depressive symptoms predict 12-month prognosis in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Risk 2002; 9(3): 153–60

Cohen HW, Madhavan S, Alderman MH. History of treatment for depression: risk factor for myocardial infarction in hypertensive patients. Psychosom Med 2001; 63(2): 203–9

Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, et al. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) randomized trial. JAMA 2003; 289(23): 3106–16

Van den Brink RH, van Meile JP, Honig A, et al. Treatment of depression after myocardial infarction and the effects on cardiac prognosis and quality of life: rationale and outline of the Myocardial Infarction and Depression-Intervention Trial (MIND-IT). Am Heart J 2002; 144(2): 219–25

Rourke SB, Halman MH, Bassel C. Neurocognitive complaints in HIV-infection and their relationship to depressive symptoms and neuropsychological functioning. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1999; 21(6): 737–56

Chwastiak L, Ehde DM, Gibbons LE, et al. Depressive symptoms and severity of illness in multiple sclerosis: epidemiologic study of a large community sample. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(11): 1862–8

Blotcky AD, Cohen DG, Conatser C, et al. Psychosocial characteristics of adolescents who refuse cancer treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol 1985; 53: 729–31

Gilbar O, DeNour AK. Adjustment to illness and dropout of chemotherapy. J Psychosom Res 1989; 33: 1–5

Hopwood P, Stephens RJ. Depression in patients with lung cancer: prevalence and risk factors derived from quality-of-life data. J Clin Oncol 2000 Feb; 18(4): 893–903

Finkelstein FO, Watnick S, Finkelstein SH, et al. The treatment of depression in patients maintained on dialysis. J Psychosom Res 2002; 53: 957–60

Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58(1): 55–61

Centers for Disease Control. Mental Health: a report of the surgeon general [online]. Available from URL: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth/home/html [Accessed 2005 Jun 3]

Lin EH, Von Korff M, Katon W, et al. The role of the primary care physician in patients’ adherence to antidepressant therapy. Med Care 1995; 33: 67–74

Telford R, Hutchinson A, Jones R, et al. Obstacles to effective treatment of depression: a general practice perspective. Fam Pract 2002 Feb; 19(1): 45–52

Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, Rost K, et al. Treating depression in staff-model versus network-model managed care organizations. J Gen Intern Med 1999 Jan; 14(1): 39–48

Rundall TG, Shortell SM, Wang MC, et al. As good as it gets? Chronic care management in nine leading US physician organizations. BMJ 2003; 325(7370): 958–61

Worrall G, Angel J, Chaulk P, et al. Effectiveness of an educational strategy to improve family physician’s detection and management of depression: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 1999; 161: 37–40

Katzelnick DJ, Simon GE, Pearson SD, et al. Randomized trial of a depression management program in high utilizers of medical care. Arch Fam Med 2000; 9: 345–51

Banerjee S, Shamash K, Macdonald AJ, et al. Randomised controlled trial of effect of intervention by psychogeriatric team on depression in frail elderly people at home. BMJ 1996; 313: 1058–61

Simon GE, Katon WJ, Von Korff M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158(10): 1638–44

Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Duan N, et al. Long-term effectiveness of disseminating quality improvement for depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001 Jul; 58(7): 696–703

Lin EHB, Simon GE, Katon WJ, et al. Can enhanced acute-phase treatment of depression improve long-term outcomes? A report of randomized trials in primary care. Am J Psychiatry 1999 Apr; 156(4): 643–5

Schoenbaum M, Kelleher K, Lave JR, et al. Exploratory evidence on the market for effective depression care in Pittsburgh. Psychiatr Serv 2004; 55(4): 392–5

Frank RG, Huskamp HA, Pincus HA. Aligning incentives in the treatment of depression in primary care with evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Serv 2003 May; 54(5): 682–7

Thompson D, Hylan TR, McMullen W, et al. Predictors of a medical-offset effect among patients receiving antidepressant therapy. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155(6): 824–7

Schoenbaum M, Unutzer J, McCaffrey D, et al. The effects of primary care depression treatment on patients’ clinical status and employment. Health Serv Res 2002; 37(5): 1145–58

Rubenstein LV, Jackson-Triche M, Unutzer J, et al. Evidence-based care for depression in managed primary care practices. Health Aff 1999 Sep–Oct; 18(5): 89–105

Leatherman S, Berwick D, Iles D, et al. The business case for quality: case studies and an analysis. Health Aff 2003 Mar–Apr; 22(2): 17–30

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grant (K23 MH01882-01A1, Kramer).

The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kramer, T.L., Beaudin, C.L. & Thrush, C.R. Evaluation and Treatment of Depression (Part I). Dis-Manage-Health-Outcomes 13, 295–306 (2005). https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200513050-00002

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200513050-00002