Abstract

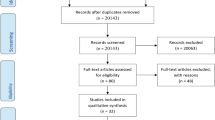

An international literature search was conducted to identify studies published since 1995 examining the effects of diabetes self-management education (DSME) in community settings. Of the 24 publications identified, eight were examined to provide a discussion of intervention methods, the use by study authors of behavioral theories and models to explain cognitive and psychosocial processes, the employment of community partnerships and collaborations to enhance patient and community ownership of DSME, and the effects of DSME on intermediate- and short-term outcomes. Reported intermediate outcomes established that researchers are now beginning to recognize the complexity of diabetes.

Interventions across publications included the use of lay health educators, family members in learning sessions, exercise classes in the community, support groups, and cooking demonstrations. Only two of eight studies identified a behavioral theory to explain cognitive and psychosocial processes. The lead agencies in all eight studies were medical universities or diabetes clinics that worked closely with community partners to deliver DSME in community settings. Community partners included diabetes centers, local churches, residential centers, and work sites. Studies in this review examined the effect of DSME on intermediate outcomes that included exercise, self-care behaviors, dietary habits, clinical service usage, self-esteem, social support, diabetes knowledge, and health beliefs, with one or more studies finding improvements in dietary habits, exercise, and diabetes knowledge. Short-term outcomes such as fasting glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), body mass index, weight, blood pressure, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and impaired glucose tolerance were also examined.

In at least one study, DSME favorably affected HbA1c, cholesterol, body mass index, blood pressure, and fasting glucose. Studies discussed in this review demonstrated the effectiveness of a single DMSE intervention delivered in community settings. DSME has proven effective in improving both intermediate- and short-term outcomes. This review also revealed opportunities to improve the effectiveness of DSME studies in community settings.

Future DSME studies should give more attention to identifying appropriate behavioral theories or models that help explain the mediating effects of cognitive and psychological processes on diabetes self-management. DSME studies in the future should continue to improve study designs to strengthen the credibility of research findings, use both qualitative and quantitative methods to capture intervention effects; and engage community members and partners in developing, implementing, and evaluating DSME interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

King H, Aubert RE, Herman WH. Global burden of diabetes, 1995–2025: prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care 1998; 21: 1414–31.

de Vegt F, Dekker J, Jager A, et al. Relation of impaired fasting and postload glucose with incident type 2 diabetes in a Dutch population. JAMA 2001; 285: 2109–13.

Narayan KM, Gregg EW, Fagot-Campagna A, et al. Diabetes: a common, growing, serious, costly, and potentially preventable public health problem. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2000; 50 Suppl. 2: S77–84.

World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. Diabetes mellitus in Europe: a problem at all ages in all countries: a model for prevention and self care (Meeting proceedings). G Ital Diabetol 1990; 10: 12–4.

World Health Organization (European Region) and the International Diabetes Education (Europe). The Lisbon Statement. Diabet Med 1997; 14: 517–8.

Amos AF, McCarty DJ, Zimmet P, et al. The rising global burden of diabetes and its complications: estimates and projections to the year 2010. Diabet Med 1997; 14 Suppl. 5: S1–S85.

Frank V. Is diabetes a public health disorder? Diabetes Care 1994; 17: 22–7.

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 393–403.

Feudtner C. A disease in motion: diabetes history and the new paradigm of transmuted disease. Perspect Biol Med 1996; 39: 157–70.

Gilmer TP, O’Connor PJ, Manning WG, et al. The cost to health plans of poor glycemic control. Diabetes Care 1997; 20: 1847–53.

Herman WH, Brandie M, Zhang P, et al. Costs associated with the primary prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 36–47.

Safran MA, Vinicor F. The war against diabetes: how will we know if we are winning? Diabetes Care 1999; 22: 508–16.

Gifford S, Zimmet P. A community approach to diabetes education in Australia: the Region 8 (Victoria) Diabetes Education and Control Program. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1986; 2: 105–12.

Fisher L, Weihs KL. Can addressing family relationships improve outcomes in chronic disease? Report of the National Working Group on family-based interventions in chronic disease. J Fam Pract 2000; 49: 561–6.

Herman WH, Thompson TJ, Visscher W, et al. Diabetes mellitus and its complications in an African American community: Project DIRECT. J Natl Med Assoc 1998; 90: 147–56.

Hiss RG, Anderson RM, Hess GE, et al. Community diabetes care: a 10-year perspective. Diabetes Care 1994; 17: 1124–34.

World Health Organization. Health systems: improving performance. Geneva: WHO, Geneva, 2000.

Kenny CJ, Pierce M, McGerty S. A survey of diabetes care in general practice in Northern Ireland. Ulster Med J 2002; 71: 10–6.

Triomphe A. The socio-economic cost of diabetes complications in France. Diabet Med 1991; 8: S30–2.

Lacroix A. Diabetes mellitus: the different costs to the patient [abstract]. Patient Education 2000. International Congress on Treatment of Chronic Disease; 1994 Jun 1, Geneva.

Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 977–86.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UK-PDS) Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes. BMJ 1998; 317: 703–13.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study. VIII study design progress and performance: a multi-center study. Diabetologia 1991; 34: 877–90.

Wake N, Hisashige A, Katayma T, et al. Cost-effectiveness of intensive insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes: a 10-year follow-up of the Kumanoto study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2000; 48: 201–10.

Ohkubo Y, Kishikawa H, Araki E. Intensive insulin therapy prevents the progression of diabetic microvascular complications in Japanese patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: a randomized prospective 6-year study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1995; 28: 103–17.

American Diabetes Association. Clinical practice recommendations: 1997. Diabetes Care 1997; 20 Suppl. 1: S5–S70.

Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 1997; 20: 1183–97.

The Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2001; 24 Suppl.: S5-S20.

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group data collection checklist. Aberdeen: University of Aberdeen, 1998.

Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, et al. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA 2002; 288: 2469–75.

Glasgow RE, Anderson RM. In diabetes care, moving from compliance to adherence is not enough: something entirely different is needed. Diabetes Care 1999; 22: 2090–2.

Funnell MM, Anderson RM, Arnold MS, et al. Empowerment: an idea whose time has come in diabetes education. Diabetes Educ 1991; 17: 37–41.

Corbin J, Strauss A. Unending work and care: managing chronic illness at home. San Fancisco (CA): Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1988.

Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Venkat Naryan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 561–87.

American Diabetes Association. Nutrition recommendations and principles for people with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2001; 24 Suppl. 1: S44–7.

Kolbe J. The influence of socioeconomic and psychological factors on patient adherence to self-management strategies: lessons learned in asthma. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2002; 10: 551–70.

Task Force to Revise the National Standards. The American Diabetes Association. national standard for diabetes self-management education programs. Diabetes Educ 1995; 21: 189–93.

Padgett D, Mumford E, Hynes M, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of educational and psychosocial interventions on management of diabetes mellitus. J Clin Epidemiol 1988; 41: 1007–30.

American Association of Diabetes Educators. Diabetes educational and behavioral research summit. Diabetes Educ 1999; 25 Suppl.: 1–3.

Clement S. Diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care 1995; 18:1204–14.

Brown SA. Meta-analysis of diabetes patient education research: variations in intervention effects across studies. Res Nurs Health 1992; 15: 409–19.

Brody GH Jack Jr L, Murry VM, Landers-Potts M, et al. Heuristic model linking contextual processes to self-management in African American adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ 2001; 27: 685–93.

Spiegel JM, Bonet Mariano B, Yassi A, et al. Developing ecosystem health indicators in Centro Habana: a community-based approach. Ecosystem Health 2001; 7: 15–26.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 1999; 89: 1322–7.

Rabin C, Amir S, Nardi R, et al. Compliance and control: issues in group training for diabetics. Health Soc Work 1986; 11: 141–51.

Nurymberg K, Kreitler S, Weissler K. The cognitive orientation of compliance in short- and long-term type 2 diabetic patients. Patient Educ Couns 1996; 29: 25–39.

Price MJ. Qualitative analysis of the patient-provider interactions: the patient’s perceptive. Diabetes Educ 1989; 15: 144–8.

Jack L, Liburd L, Vinicor F, et al. Influence of the environmental context on diabetes self-management: a rationale for developing a new research paradigm in diabetes education. Diabetes Educ 1999; 25: 775–90.

Levin-Zamir D, Peterburg Y. Health literacy in health systems: perspectives on patient self-management in Israel. Health Promot Internation 2001; 16: 87–94.

Anderson R, Funnell M, Carlson A, et al. Facilitating self-care through empowerment. In: Snoek F, Skinner T, editors. Psychology in diabetes care. Chichester County: John Wiley & Sons, 1999: 221–47.

Clark N, Becker M, Janz N, et al. Self-management of chronic disease by older adults: a review and questions for research. J Aging Health 1991; 3: 3–16.

International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Diabetes Health Economics. Diabetes health economics: facts, figures, and forecasts. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation, 1997.

Jean-Philippe A. Cost-effectiveness of diabetes education. Pharmacoeconomics 1995; 8 Suppl. 1: 68–71.

Selby JV, Ray D, Zhang D, et al. Excess costs of medical care for patients with diabetes in a managed care population. Diabetes Care 1997; 20: 1396–402.

Gotler RS, Flocke SA, Goodwin MA, et al. Facilitating participatory decision-making: what happens in real-world community practice? Med Care 2000; 38: 1200–9.

Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Butler PM, et al. Patient empowerment: results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 1995; 18: 943–9.

Vinicor F. The public health burden of diabetes and the reality of limits. Diabetes Care 1998; 21 Suppl. 3: S15–8.

Glasgow RE, Osteen VL. Evaluating diabetes education: are we measuring the right outcomes? Diabetes Care 1992; 15: 1423–32.

Cagan ER, Hubinsky T, Goodman A, et al. Partnering with communities to improve health: the New York City Turning Point experience. J Urban Health 2001; 78: 176–80.

Mur-Veeman I, Eijkelberg I, Spreeuwenberg C. How to manage the implementation of shared care: a discussion of the role of power, culture and structure care arrangements. J Manag Med 2001; 15: 142–55.

Gittelsohn J, Harris S, Whitehead S. Developing diabetes interventions in an Ojibwa-Cree community in Northern Ontario: linking qualitative and quantitative data. Chronic Dis Can 1995; 16: 157–63.

Gamm LD. Advancing community health through community health partnerships. J Healthc Manag 1998; 43: 51–67.

Voyle JA, Simmons D. Community development through partnerships: promoting health in an urban indigenous community in New Zealand. Soc Sci Med 1999; 49: 1035–50.

Babacan H, Gopalkrishnan N. Community work partnerships in a global context. Community Dev J 2001; 36: 3–17.

Ansari Z, Carson N, Serraglio A, et al. The Victorian Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions study: reducing demand on hospital services in Victoria. Aust Health Rev 2002; 25: 71–7.

Community Health Improvement Partners. From the board room to the community room: a health improvement collaboration that’s working. J Qual Improve 1998; 24: 549–64.

Krein SL, Klamerus ML. Michigan Diabetes Outreach Networks: a public health approach to strengthening diabetes care. J Community Health 2000; 25: 495–511.

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the development of a national programme for diabetes mellitus. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1991.

Simmons D, Voyle J, Swinburn B, et al. Community-based approaches for the primary prevention of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 1997; 14: 519–26.

Engelgau MM, Narayan KM, Geiss LS, et al. A project to reduce the burden of diabetes in the African-American community: Project DIRECT. J Natl Med Assoc 1998; 90: 605–13.

Brown SA, Upchurch SL, Garcia AA, Boston SA, Hanis CL Symptom-related self-care of Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes: preliminary findings of the Starr County Diabetes Education Study. Diabetes Educ 1998; 24: 331–9.

Elshaw EB, Young EA, Saunders MJ, et al. Utilizing a 24-hour dietary recall and culturally specific diabetes education in Mexican Americans with diabetes. Diabetes Educ 1994; 20: 228–35.

Wang CY, Abbott L, Goodbody, et al. Development of a community-based diabetes management program for Pacific Islanders. Diabetes Educ 1999; 25: 738–46.

Brown SA. Studies of educational interventions and outcomes in diabetic adults: a meta-analysis revisited. Patient Educ Couns 1990; 16: 189–215.

Norris SL, Nichols PJ, Caspersen CJ, et al. Increasing diabetes self-management education in community settings: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2002; 22(4 Suppl.): 39–66.

Sorensen G, Emmons K, Hunt MK, et al. Implications of the results of community intervention trials. Annu Rev Public Health 1998; 19: 379–416.

Chowdhury AM, Helman C, Greenhalgh T. Food beliefs and practices among British Bangladeshis with diabetes: implications for health education. Anthropology Med 2000; 7: 209–26.

Brisco VJ, Pickert JW. Evaluation of a program to promote diabetes care via existing agencies in African-American communities. ABNF J 1999 Sep/Oct; 12: 111–15.

Davidson MR. Diabetes management: improving care in HMO and community settings. Dis Manag 1997 Aug; 10: 86–90.

Hanley AJG, Harissis SB, Barnie A, et al. The Sandy Lake Health and Diabetes Project: design, methods and lessons learned. Chronic Dis Can 1995; 16: 149–56.

Tregonning PB, Simmons D, Fleming C. A community diabetes educator course for the unemployed in South Auckland, New Zealand. Diabetes Educ 2001; 27: 94–100.

Coffman S. Community partnerships for parent-to-parent support. Diabetes Educ 2001; 27: 36–40.

Herbert CP. Community-based research as a tool for empowerment: the Haida Gwaii Diabetes Project example. Can J Public Health 1996; 87(2): 109–12.

Berg GD, Wadhwa S. Diabetes disease management in a community-based setting. Manag Care 2002 Jun; 11 (6): 42–50.

Naryan KM, Hoskin M, Kozak D, et al. Randomized clinical trial of lifestyle interventions in Pima Indians: a pilot study. Diabet Med 1998; 15: 66–72.

Hawthorne K. Effect of culturally appropriate health education on glycemic control and knowledge of diabetes in British Pakistani women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Health Educ Res 2001; 16: 373–81.

Mau MK, Glanz K, Severino R, et al. Mediators of lifestyle behavior change in Native Hawaiians: initial findings from the native Hawaiian Diabetes Intervention Program. Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 1770–5.

Heffernan C, Herbert C, Grams GD. The Haida Gwaii Diabetes Project: planned response activity outcomes. Health Soc Care Community 1999; 7: 379–86.

Daniel M, Green LW, Marion SA, et al. Effectiveness of community-directed diabetes prevention and control in a rural Aboriginal population in British Columbia, Canada. Soc Sci Med 1999; 48: 815–32.

Simmons D, Fleming C, Voyle J, et al. A pilot urban church-based programme to reduce risk factors for diabetes among western Samoans in New Zealand. Diabet Med 1998; 15: 136–42.

Lowe JM, Bowen K. Evaluation of a diabetes education program in Newcastle, NSW. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1997; 38: 91–9.

Leonard B, Leonard C, Wilson R. Zuni diabetes project. Public Health Rep 1996; 101: 282–8.

Brown SA, Hanis CL. A community-based, culturally sensitive education and group-support interventions for Mexican Americans with NIDDM: a pilot study of efficacy. Diabetes Educ 1995; 21: 203–10.

Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ. Socioeconomic status differences in recreational physical activity levels and real and perceived access to a supportive physical environment. Prev Med 2002; 35: 601–11.

Eyler AA, Matson-Koffman D, Vest JR, et al. Environmental, policy, and cultural factors related to physical activity in a diverse sample of women: The Women’s Cardiovascular Health Network Project: summary and discussion. Women Health 2002; 36: 123–34.

Toljamo M, Hentinen M. Adherence to self-care and social support. J Clin Nurs 2001; 10: 618–27.

Cheadle A, Psaty BM, Curry S, et al. Can measures of the grocery store environment be used to track community-level dietary changes? Prev Med 1993; 22: 361–72.

Jack Jr L, Liburd L, Tirzah S, Airhihenbuwa CO. Moving public health intervention into the community: will that be enough? Ann Intern Med. In press.

Krieger N, Zierler S. What explains the public’s health? A call for epidemiologic theory. Epidemiology 1996; 7: 107–9.

Krieger N, Zierler S. The need for epidemiologic theory. Epidemiology 1997; 8: 212–4.

Rychetnik L, Frommer M, Hawe P, et al. Criteria for evaluating evidence on public health interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002; 56: 119–27.

Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Prentice-Hall, 1986.

Ajzen I. Attitudes, personality and behavior. Buckingham: Open University, 1992.

Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health promotion planning: an educational and environmental approach. Mountain View (CA): Mayfield Publishing Company, 1999.

Rosenstock IM, Stretcher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ Q 1988; 15: 175–83.

Airhihenbuwa CO, King G, Spencer T. The global contexts of health behavior research: implications for medicine and health. Ann Behav Sci Med Educ 2001; 7: 69–75.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol 1982; 37: 122–47.

DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research: strategies for improving public health. New York: Jossey-Bass, 2002.

Goodman RM, Liburd LC, Green-Phillips A. The formation of a complex community program for diabetes control: lessons learned from a case study of project DIRECT. J Public Health Manag Pract 2001; 7: 19–29.

Krumeich A, Weijts W, Reddy P, et al. The benefits of anthropological approaches for health promotion research and practice. Health Educ Res 2001; 16: 121–30.

Acknowledgements

The author did not use any sources of funding to prepare this manuscript and does not have any potential conflict of interest relevant to its contents.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jack, L. Diabetes Self-Management Education Research. Dis-Manage-Health-Outcomes 11, 415–428 (2003). https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200311070-00002

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200311070-00002