Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the use of antidepressants through use of mutually exclusive disease indications using a managed care database.

Design and setting

A claims database from a 225 000 member managed care organisation was used for the study. A hierarchy of mutually exclusive antidepressant indications was developed: ‘Depression’, ‘Other Approved Indication’, ‘Mental Health’, ‘Surrogate Diagnosis’, ‘Other Uses’, ‘Chronic Disease’, and a residual ‘Unclassified’ hierarchical indication group.

Main outcome measures and results

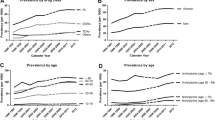

Patients in the Depression and Other Approved Indication hierarchical groups likely received the antidepressant drugs primarily for these indications and frequently received selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Use of antidepressants in the Mental Health Disorders hierarchical group may have been for a related disease. The patients in the Surrogate Diagnosis, Other Uses, Chronic Diseases, and Unclassified hierarchical groups were significantly older than those patients in the Depression group and tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) use was more frequent than the SSRIs. The patients in the Unclassified diagnosis group may represent antidepressant use that is not adequately documented or not indicated. The Surrogate Diagnosis and Chronic Diseases hierarchical groups total healthcare costs were significantly higher than those observed in patients with a Depression diagnosis.

Conclusions

Use of mutually exclusive hierarchical diagnosis groups proved to be a useful strategy for assessing antidepressant drug use. SSRI use was more common in the Depression and Other Approved Indication hierarchical groups. Patients in the Surrogate Diagnosis, Other Uses, Chronic Diseases, and Unclassified hierarchical groups used TCAs more frequently.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rupp A, Narrow W, Rigueur D, et al. Epidemiology and costs of depression: a hidden burden. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 1997; 2: 134–40

Hirschfeld RMA, Keller MB, Panico S, et al. The national depressive and manic-depressive association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 1997; 277: 333–40

Cambell LK, Robison LM, Skaer TL, et al. Depression. Interventions and their effectiveness. Dibs Manage Health Outcomes 1997; 2: 223–37

Fairman KA. ’The doctor told me to cut the pills in half’: practical considerations in using claims databases for outcomes research. Drug Benefit Trends 1997; 9: 30–6

Anderson IM. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability. J Affect Disord 2000; 58: 19–36

Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, Jefferson JW, et al. Prescribing patterns of antidepressant medications for depression in a HMO. Hosp Formul 1996; 31: 374–88

Anderson IM. SSRIs versus tricyclic antidepressants in depressed inpatients: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability. Depress Anxiety 1998; 7 Suppl. 1: 11–7

Simon GE, Von Korff M, Heiligenstein JH, et al. Initial antidepressant choice in primary care. Effectiveness and cost of fluoxetine vs tricyclic antidepressants. JAMA 1996; 275: 1897–902

Streator SE, Moss JT. Identification of off-label antidepressant use and costs in a network model HMO. Drug Benefit Trends 1997; 9: 42–56

Valdez C, Grier D. Determining the most economical SSRI for a Medicare risk contract. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1999; 56: 23–4

Hutchins DS, Klein EG, Signa WF, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor utilization patterns: consistency across research designs. Clin Ther 1998; 20: 797–805

Gevirtz F, Way K, Young CH, et al. SSRI-to-SSRI switching and associated dosing characteristics. J Managed Care Pharm 1999; 5: 138–43

Browne RA, Melfi CA, Croghan TW, et al. Data analysis issues to consider when conducting research using physician-reported antidepressant claims. Drug Benefit Trends 1998; 10: 33–42

Broadhead WE, Larson DB, Yarnall KSH, et al. Tricyclic antidepressant prescribing for nonpsychiatric disorders. J Fam Pract 1991; 33: 24–32

Wells BG, Jann MW, Marken P, et al. APhA special report. Therapeutic options in the treatment of depression. Am Pharm Assoc Special Report 1994: 1-20

McCoombs JS, Nichol MB, Stimmel GL. The role of SSRI antidepressants for treating depressed patients in the California Medicaid (Medi-Cal) program. Value Health 1999; 2: 269–80

Russell JM, Berndt ER, Miceli R, et al. Course and cost of treatment for depression with fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline. Am J Managed Care 1999; 5: 597–606

Thompson D, Buesching D, Gregor KJ, et al. Patterns of antidepressant use and their relation to costs of care. Am J Managed Care 1996; 2: 1239–46

Hartman T, Watanabe MD. Pharmacotherapy of depression: focused considerations for primary care. J Am Pharm Assoc 1996; NS36: 521–33

Blandford L, Dans PE, Ober JD, et al. Analyzing variations in medication compliance related to individual drug, drug class, and prescribing physician. J Managed Care Pharm 1999; 5: 47–51

Moss JT. Editorial comment concerning manuscript Data analysis issues to consider when conducting research using physician-reported antidepressant claims. Drug Benefit Trends 1998; May: 37

Rost K, Smith GR, Matthews DB, et al. The deliberate misdiagnosis of major depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med 1994; 3: 333–7

Jencks SF. Recognition of mental disorder in primary care. JAMA 1985; 253: 1903–7

Lloyd SS, Rissing JP. Physician coding errors in patient records. JAMA 1985; 254: 1330–6

Jencks SJ. Accuracy in recorded diagnoses. JAMA 1992; 267: 2238–9

Bright RA, Avorn J, Everitt DE. Medicaid data as a resource for epidemiologic studies: strengths and limitations. J Clin Epidemiol 1989; 42: 937–45

Hsia DC, Krushat WM, Fagan AB, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic coding for Medicare patients under the prospective payment system. N Engl J Med 1988; 318: 352–5

Motheral BR, Fairman KA. The use of claims databases for outcomes research: rationale, challenges, and strategies. Clin Ther 1997; 19: 346–66

Strom BL, Carson JL. Use of automated databases for pharmacoepidemiology research. Epidemiol Rev 1990; 12: 87–107

Garnick DW, Hendricks AM, Comstock CB. Measuring quality of care: fundamental information from administrative datasets. Int J Quality Health Care 1994; 6: 163–77

Lohr KN. Use of insurance claims data in measuring quality of care. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1990; 6: 263–71

Tierney WM, McDonald CJ. Practice databases and their uses in clinical research. Stat Med 1991; 10: 541–57

Davey PG. Cost management in community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections. Am J Med 1995; 99 Suppl. 6B: 20S–23S

Armstrong EP, Manuchehri F. Ambulatory care databases for managed care organizations. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1997; 54: 1973–83

Beto JA, Geraci MC, Marshall PA, et al. Pharmacy computer prescription databases: methodologic issues of access and confidentiality. Ann Pharmacother 1992; 26: 686–91

Selby JV. Linking automated databases for research in managed care settings. Ann Intern Med 1997; 127: 719–24

Lewis NJW, Patwell JT, Briesacher BA. The role of insurance claims databases in drug therapy outcomes research. Pharmacoeconomics 1993; 4: 323–30

McDonald CJ, Overhage M, Dexter P, et al. A framework for capturing clinical data sets from computerized sources. Ann Intern Med 1997; 127: 675–82

Arnold RG, Kotsanos JG, Motheral B, et al. Panel 3: methodological issues in conducting pharmacoeconomic evaluations — retrospective and claims database studies. Value Health 1999; 2: 82–7

Weiner JP, Parente ST, Garnick DW, et al. Variation in officebased quality. A claims-based profile of care provided to medicare patients with diabetes. JAMA 1995; 273: 1503–8

Iezzoni LI. Assessing quality using administrative data. Ann Intern Med 1997; 127: 666–74

Glauber HS, Brown JB. Use of health maintenance organization data bases to study pharmacy resource usage in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 1992; 15: 870–6

Else BA, Armstrong EP, Cox ER. Data sources for pharmacoeconomic and health services research. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1997; 54: 2601–8

Ray WA. Policy and program analysis using administrative databases. Ann Intern Med 1997; 127: 712–8

Quam L, Ellis LBM, Venus P, et al. Using claims data for epidemiologic research. The concordance of claims-based criteria with the medical record and patient survey for identifying a hypertensive population. Med Care 1993; 131: 498–507

Palmer RH. Process-based measures of quality: the need for detailed clinical data in large health care databases. Ann Intern Med 1997; 127: 733–8

Larson LN, Bjornson DC. Interface between pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics in managed care pharmacy. J Managed Care Pharm 1996; 2: 282–9

Weiner JP, Powe NR, Steinwachs DM, et al. Applying insurance claims data to assess quality of care: a compilation of potential indicators. QRB Q Rev Bull 1990; 16: 424–38

Piecoro LT, Wang LS, Dixon WS, et al. Creating a computerized database from administrative claims data. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 1999; 56: 1326–9

Acknowledgements

The research project was funded by a research grant from Eli Lilly.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Armstrong, E.P. Analysis of Antidepressant Use Through Hierarchical Disease Analysis. Dis-Manage-Health-Outcomes 9, 255–267 (2001). https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200109050-00003

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200109050-00003