Abstract

Uveitis, or intraocular inflammation, remains an ongoing challenge to ophthalmologists and patients alike. In most patients, uveitis is limited to the anterior ocular structures and is readily managed with topical steroids. The inflammatory process can extend behind the lens to involve the pars plana, the vitreous cavity, the choroid and the retina. These intermediate and posterior uveitides are relatively rare but contribute disproportionately to visual morbidity and present serious diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties.

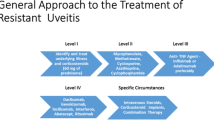

Systemic steroids constitute the first line of treatment for most sight-threatening uveitides. Their long term use is limited by universal and debilitating adverse effects. Second-line, steroid-sparing agents allow a reduction in steroid dosage. Cyclosporin and azathioprine are the main steroid-sparing agents currently in use. However, these compounds are limited by a narrow therapeutic window and significant adverse effects.

This paper offers a brief discussion of some of the immune mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of uveitis and reviews categories of investigational compounds.

Inhibitors of T cell function: tacrolimus (previously FK506), licensed for use in liver transplantation, and sirolimus (rapamycin) are macrolide antibiotics. Sirolimus is a functional cytokine antagonist and in vitro studies suggest it could be up to 100 times more potent than cyclosporin. Drug synergy between sirolimus and cyclosporin has been demonstrated, resulting in immunosuppression at lower drug doses and with fewer adverse effects.

Nucleotide synthesis inhibitors: mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and leflunomide. Human lymphocytes are only able to synthesise nucleic acids de novo. Having no alternative or ‘salvage’ pathway, they are exquisitely sensitive to interference with the de novo nucleotide synthesis enzymatic pathway. MMF is a purine synthesis inhibitor. Compared to other purine inhibitors, early data suggest that MMF is more efficacious and less toxic than azathioprine. Leflunomide is an inhibitor of pyrimidine synthesis.

Monoclonal surface receptor antibodies and immunoadhesins: the IL-2 receptor is essential for clonal expansion of activated T cells; this has led to the development of anti-IL-2 receptor antibodies. Daclizumab is a genetically engineered humanised IgG1 monoclonal antibody. In conjunction with cyclosporin, it significantly reduces renal allograft rejection rates and is also showing promise in the treatment of T cell mediated autoimmune disorders. The mechanism of action of monoclonal antibodies to other pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL-12 and data from animal and human uveitis trials are also discussed. Finally, new avenues of research in immunopharmaco-modulation are mentioned.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bloch-Michel E, Nussenblatt RB. International Uveitis Study Group recommendation for the evaluation of intraocular inflammatory disease. Am J Ophthalmol 1987; 103: 234–5

Tran VT, Auer C, Guex-Croisier, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of uveitis in Switzerland. Int Ophthalmol 1994–95; 18 (5): 293–8

Baarsma GS. The epidemiology and genetics of endogenous uveitis. Curr Eye Res 1992; 11 Suppl. : 1–9

Suttorp-Van Schulten MSA, Rothova A. The possible impact of uvetis in blindness: a literature survey. Br J Ophthalmol 1996; 80: 844–8

Nussenblatt RB. The natural course of uveitis. Int Ophthalmol 1990; 141: 303–8

Rothova A, Buitenhuis HJ, Meenken C, et al. Uveitis and systemic disase. Br J Ophthalmol 1992; 76: 137–41

Dev S, McCallum RM, Jaffe GJ. Methotrexate treatment for sarcoid-associated panuveitis. Ophthalmology 1999; 106 (1): 111–8

Shetty AK, Zganjar BE, Ellis Jr GS, et al. Low-dose methotrex atein the treatment of severe juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and sarcoid iritis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1999; 36 (3): 125–8

Sullu Y, Oge I, Erkan D, et al. Cyclosporin-A therapy in severe uveitis of Behçet’s disease. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 1998 Feb; 76 (1): 96–9

Greenwood AT, Stanford MR, Graham EM. The role of azathioprine in the management of retinal vasculitis. Eye 1998; 12 Pt 5: 783–8

Jiang LQ, Jorquera M, Streilein JW. Subretinal space and vitreous cavity as immunologically privileged sites for retinal allografts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1993; 34: 3347–5

Chan CC, Natteson DM, Li Q, et al. Apoptosis in patients with posterior uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1997; 115 (2): 1559–67

Mosman TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, et al. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol 1986 Apr; 136 (7): 2348–57

Cherwinski HM, Schumacher JH, Brown KD, et al. Two types of mouse helper T cell clone. III. Further differences in lymphokine synthesis between Th1 and Th2 clones revealed by RNA hybridization, functionally monospecific bioassays, and monclonal antibodies. J Exp Med 1987; 166 (5): 1229–44

Constant SL, Bottomley K. Induction of Thl and Th2 CD4+ T cell responses: the alternative approach. Annu Rev Immunol 1997; 15: 297–322

Nussenblatt RB, Mittal KM, Ryan S, et al. Birdshot retinochoroidopathy associated with HLA-A29 antigen and immune responsiveness to retinal S-antigen. Am J Ophthalmol 1982; 94: 147–58

Baarsma GS, Priem HA, Kijlstra A. Association of birdshot retinochoroidopathy and HLA-A29 antigen. Curr Eye Res 1990; 9 Suppl. : 63–8

Kapasi K, Chui B, Inman RD. HLA-B27/microbial mimicry: an in vivo analysis. Immunology 1992 Nov; 77 (3): 456–61

Lahesmaa R, Skurnik M, Toivanen P. Molecular mimicry: any role in the pathogenesis of spondyloarthropathies? Immunol Res 1993; 12 (2): 193–208

Kahan BD, Flechner SM, Lorber MI, et al. Complications of cyclosporin therapy. World J Surg 1986; 10: 348–60

Cockburn I. Assessment of the risks of malignancy and lymphomas in patients using Sandimmune. Transplant Proc 1987; 19: 1804–7

Hrelia P, Murelli L, Scotti M, et al. Organospecific activation of azathioprine in mice: role of liver metabolism in mutation induction. Carcinogenesis 1988; 9: 1011–5

Dick AD, Isaacs JD. Immunomodulation of autoimmune responses with monoclonal antibodies and immunoadhesins: treatment of ocular inflammatory disease in the next millenium. Br J Ophthalmol 1999; 83: 1230–4

Kino T, Hatanaka H, Hashimoto M, et al. FK 506, a novel immunosuppressant isaolated form Streptomyces. I. Fermentation isolation: physico-chemical and biological characteristics. J Antibiot 1987; 40: 1249–55

Fung J, Abu-Elmagd K, Jain A, et al. A randomized trial of primary liver transplantation under immunosuppression with FK506 vs cyclsosporin. Transplant Proc 1991; 23: 2977–83

Clipstone NA, Crabtree GR. Identification of calcineurin as a key signalling enzyme in T lymphocyte activation. Nature 1992; 357: 695–7

O’Keefe SJ, Tamura J, Kincaid RL, et al. FK-506- and CSA-sensitive activation of the interleukin-2 promoter by calcineurin. Nature 1992 Jun; 357 (6380): 692–4

Sigal NH, Dumont FJ. Cyclosporin A, FK-506 and rapamycin: pharmacologic probes of lymphocyte signal transduction. Annu Rev Immunol 1992; 10: 519–60

Tocci MJ, Matkovich DA, Collier KA, et al. The immunosuppressant FK 506 selectively inhibits expression of early T cell activation genes. J Immunol 1989; 143: 718–26

Venkataraman R, Jain A, Warty VS, et al. Pharmocokinetics of FK506 in transplantation: preclinical and clinical studies. Transplant Proc 1990; 22: 52–6

Christains U, Braum F, Sattler M, et al. Interactions of FK506 and cyclosporin metabolism. Transplant Proc 1991; 23: 2794–6

Stevens C, Lempert N, Freed BM. The effects of immunosuppressive agents on in vitro production of human immunoglobulins. Transplantation 1991; 51: 1240–4

Sawada S, Suzuki G, Kawase Y, et al. Novel immunosuppressive agent, FK506: in vitro effects on the cloned T cell activation. J Immunol 1987; 139: 1797–803

Inamura N, Nakahara K, Kino T, et al. Prolongation of skin allograft survival in rats by a novel immunosuppressive agent, FK506. Transplantation 1988; 45: 206–9

Neylan JF, Sullivan EM, Steinwald B, et al. Assessment of the frequency and costs of posttransplantion hospitalizations in patients receiving tacrolimus versus cyclosporine. Am J Kidney Dis 1998; 32 (5): 770–7

Ni M, Chan CC, Nussenblatt RB, et al. FR900506 (FK506) and 15-deoxyspergualin (15-DSG) modulate the kinetics of infiltrating cells in eyes with experimental autoimmune uveitis. Autoimmunity 1990; 8: 43–51

Kawashima H, Fujino Y, Mochizuki M. Effects of a new immunosuppressive agent, FK506, on experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis in rats. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci 1988; 29 (8): 1265–71

Fujino Y, Okamura A, Nussenblatt RB, et al. Cyclosporin-induced specific unresponsiveness to retinal soluble antigen in experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1988; 46: 234–48

Fujino Y, Mochizuki M, Chan CC, et al. FK506 treatment of S-antigen induced uvetis in primates. Curr Eye Res 1991; 7: 679–90

Hikita N, Lopez JS, Chan CC, et al. Use of topical FK506 in a corneal graft rejection model in Lewis rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1997; 38 (5): 901–9

Reis A, Reinhard T, Sundmacher R, et al. A comparative investigation of FK506 and cyclosporine A in murine corneal transplantation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1998; 236 (10): 785–9

Mochizuki M, Masuda K, Sakane T, et al. A clinical trial of FK506 in refractory uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1993; 115: 763–9

Ishioka M, Ohno S, Nakamura S, et al. FK506 treatment of noninfectious uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1994; 118: 723–9

Kilmartin DJ, Forrester JV, Dick AD. Tacrolimus (FK506) in failed cyclosporin A therapy in endogenous posterior uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 1998 Jun; 6 (2): 101–9

Seghal SN, Baker H, Vezina C. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. II. Fermentation, isolation and characterization. J Antibiot 1975; 28: 727–32

Chang JY, Seghal SN. Pharmacology of rapamycin: a new immunosuppressive agent. Br JRheumatol 1991; 30 Suppl. 2: 62–5

Seghal SN, Bansbach CC. An in vitro immunological profile of rapamycin. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1993; 685: 58–67

Luo H, Chen H, Daloze P, et al. Effects of rapamycin on human HLA-unrestricted cell-killing. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1992; 65: 60–4

Terada N, Lucas JJ, Szepesi A, et al. Rapamycin blocks cell-cycle progression of activated T cells prior to events characteristic of the middle to late G1 phase of the cycle. J Cell Physiol 1993; 154: 7–15

Kimball PM, Kerman RH, Kahan BD. Production of synergistic, but non-identical mechanisms of immunosuppression by rapamycin and cyclosporin. Transplantation 1991; 49: 486–90

Dumont FJ, Staruch MJ, Koprak SL, et al. Distinct mechanisms of suppression of murine T-cell activation by the related macrolides FK506 and rapamycin. J Immunol 1990; 144: 251–8

Almond PS, Moss A, Nakleh RF, et al. Rapamycin, immunosuppressive and tolerogenic effects in a porcine real allograft model. Transplantation 1993; 56: 275–81

Fryer J, Yatscoff RW, Pascoe EA, et al. The relationship of blood concentrations of rapamycin and cyclosporine to suppression of allograft rejection in a rabbit heterotopic heart transplant model. Transplantation 1993; 55: 340–5

Murgia MG, Jordan S, Kahan BD. The side-effect profile of sirolimus: a phase I study in quiescent cyclospron-prednisonetreated renal transplant patients. Kidney Int 1996; 49: 209–16

Ferron GM, Mishina EV, Zimmerman JJ, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of sirolimus in kidney transplant patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1997 Apr; 61 (4): 416–28

Sedrani R, Cottens S, Kallen J, et al. Chemical modifications of rapamycin: the discovery of SDZ RAD. Transplant Proc 1998; 30: 2192–4

Roberge FG, Chan CC, de Smet MD, et al. Treatment of autoimmune neuroretinitis in the rat with rapamycin, an inhibitor of lymphocyte growth factor signal transduction. Curr Eye Res 1993; 12: 197–203

Knight R, Ferrasso M, Serino F, et al. Low-dose rapamycin potentiates the effect of subtherapeutic doses of cyclosporin to prolong renal allograft survival in the mongrel canine model. Transplantation 1993; 55: 947–9

Martin DF, DeBarge LR, Nussenblatt RB, et al. Synergistic effect of rapamycin and cyclosporin A on the inhibition of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis. J Immunol 1995; 154: 922–7

Ikeda E, Hikita N, Eto K, et al. Tacrolimus-rapamycin combination therapy for experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis. Jpn J Ophthalmol 1997; 41: 396–402

Allison AC, Eugui EM. Mycophenolate mofetil, a rationally designed immunosuppressive drug. Clin Transplant 1993; 7: 96–112

Ransom JT. Mechanism of action of mycophenolate mofetil. Ther Drug Monit 1995; 17: 681–4

Allison AC, Kowalski WJ, Muller CD, et al. Mycophenolic acid and brequinar, inhibitors of purine and pyrimidine synthesis, block the glycosylation of adhesion molecules. Transplant Proc 1993; 25: 67–70

Gosio B. Ricerche batteriologiche e chimiche sulle alterazioni del mais. Riv d’Igiene Sanita Pubblica Ann 1896; 7: 825–68

Aisberg C, Black OF. Contribution to the study of maize deterioration. US Dept of Agriculture, Bureau of Plant Industry Bulletin 1913; 270: 7–48

Eugui EM, Mirkovich A, Allison AC. Lymphocyte-selective anti-proliferative and immunosuppressive effects of mycophenolic acid in mice. Scand J Immunol 1991; 33: 175–83

Eugui EM, Almquist S, Muller CD, et al. Lymphocyte-selective cytostatic and immunosuppressive effects of mycophenolic acid in vitro: role of deoxyguanosine depletion. Scand J Immunol 1991; 33: 161–3

Lee WA, Gu L, Mikssztal AL, et al. Bioavailability improvement of mycophenolic acid through aminoester derivitization. Pharm Res 1990; 7: 161–6

Allison AC, Eugui EM. Immunosuppressive and other effects of mycophenolic acid and an ester prodrug, mycophenolate mofetil. Immunol Rev 1993; 136: 5–28

Sollinger HW, US Renal Transplant Mycophenolate Mofetil Study Group. Mycophenolate mofetil for the prevention of acute rejection in primary cadaveric renal allograft recipients. Transplantation 1995; 60: 225–32

European Mycophenolate Mofetil Cooperative Study Group. Placebo-controlled study of mycophenolate mofetil combined with cyclosporine and cortiscosteroids for prevention of acute rejection. Lancet 1995; 345: 1321–5

Hood KA, Zarembski DG. Mycophenolate mofetil: a unique immunosuppressive agent. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1997; 54 (1): 285–94

Kobashigawa JA, Renlund DG, Olsen SL, et al. Initial results of RS-61443 for refractory cardiac rejection. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 19: 203

Epinette WW, Parker CM, Jones EL, et al. Mycophenolic acid for psoriasis: a review of pharmacology, long-term efficacy, and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987; 17: 962–71

Bohm M, Beissert S, Schwartz T, et al. Bullous pemphigoid treated with mycophenolate mofetil [letter]. Lancet 1997; 349: 541

Enk AH, Knop J. Treatment of pemphigus vulgaris with mycophenolate mofetil [letter]. Lancet 1997; 350: 494

Goldblum R. Therapy of rheumatoid arthritis with mycophenolate mofetil. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1993: 11 Suppl. 8: SI 17–9

Zimmer-Molsberger G, Knauf W, Thiel E. Mycophenolate mofetil for severe autoimmune haemolytic anemia [letter]. Lancet 1997; 350: 1003–4

Lipsky JJ. Mycophenolate mofetil. Lancet 1996; 348: 1357–9

Chanaud NP, Vistica BP, Eugui E, et al. Inhibition of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis by mycophenolate mofetil, an inhibitor of purine metabolism. Exp EyeRes1995; 61: 429–34

Kilmartin DJ, Forrester JV, Dick AD. Rescue therapy with mycophenolate mofetil in refractory uveitis. Lancet 1998; 352: 35–6

Larkin G, Lightman S. Mycophenolate mofetil: a useful immunosuppressive in inflammatory eye disease. Ophthalmology 1999 Feb; 106 (2): 370–4

Siemasko KF, Chong AS, Williams JW, et al. Regulation of B-cell function by the immunosuppressive agent leflunomide. Transplantation 1961; 61: 635–42

Bartlett RR, Anagnostopulos H, Zielinski T, et al. Effects of leflunomide on immune reponses and models of inflammation. Springer Semin Immunopathol 1993; 14: 381–94

Lindner JK, Zantl N. Synergism of the malononitrilamides 279 and 715 with cyclosporine A in the induction of long-term cardiac allograft survival. Transpl Int 1998; 11 Suppl. 1: 303–9S

Strand V, Cohen S, Schiff M, et al. Treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis with leflunomide compared with placebo and methotrexate. Leflunomide Rheumatoid Arthritis Investigators Group. Arch Intern Med 1999 Nov 22; 159 (21): 2542–50

Leflunomide approved for rheumatoid arthritis; other drugs nearing approval. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1998 Nov 1; 55 (21): 2225–6

Robertson SM, Lang LS. Leflunomide: inhibition of S-antigen induced autoimmune uveitis in Lewis rats. Agents Actions 1994; 42: 167–72

Taniguchi T, Minami Y. The IL-2/IL-2 receptor system: a current overview. Cell 1993; 73: 5–8

Neuhaus B, Keck H, Bechstein WO, et al. Quadruple induction immuosuppression after liver transplantation with IL-2 receptor antibody (BT 563) is equally effective and better tolerated than ATG induction therapy. Transplant Proc 1993; 25: 587–9

Kirkman RL, Shapiro ME, Carpenter CB, et al. A randomized prospective trial of anti-TAC monoclonal antibody in human renal transplantation. Transplantation 1991; 51: 107–13

Hakimi J, Mould D, Waldmann TA, et al. Development of Zenapax: a humanized anti-tac antibody. In: Harris WJ, Adair JR, editors. Antibody therapeutics. New York (NY): CRC Press, 1997: 277–300

Vincenti F, Kirkman R, Light S, et al. Interleukin-2 receptor blockade with daclizumab to prevent acute rejection in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 1998; 338: 161–5

Guex-Crosier Y, Raber J, Chan C-C, et al. Humanized antibodies against the α-chain of the IL-2 receptor and against the ß-chain shared by the IL-2 and IL-15 receptors in a monkey uveitis model of autiommune diseases. J Immunol 1997; 158: 452–8

Nussenblatt RB, Fortin E, Schiffman R, et al. Treatment of noninfectious intermediate and posterior uveitis with the humanized anti-Tac mAb: A phase I/II clinical trial. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999; 96: 7462–6

Dick AD, McMenamin PG, Korner H, et al. Inhibition of tumour necrosis factor activity minimizes target organ damage in experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis despite quantitatively normal activated T cell traffic to the retina. Eur J Immunol 1996; 26: 1018–25

Yoko H, Kato K, Kezuka T, et al. Prevention of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis by monoclonal antibody to interleukin-12. Eur J Immunol 1997; 27: 641–6

Singh VK, Kalra HK, Yamaki K, et al. Suppression of experimental autoimmune uveitis in rats by the oral administration of the uveitopathogenic S-antigen fragment or a cross-reactive homologous peptide. Cell Immunol 1992 Jan; 139 (1); 81–90

Nussenblatt RB, Gery I, Weiner HL, et al. Treatment of uveitis by oral administration of retinal antigens: results of a phase I/II randomized masked trial. Am J Ophthalmol 1997; 123 (5): 583–92

Thurau SR, Diedrichs-Mohring M, Fricke H, et al. Oral tolerance with an HLA-peptide mimicking retinal autoantigen as a treatment of autoimmune uveitis. Immunol Lett 1999 Jun 1; 68 (2-3): 205–12

Dick AD, Kreutzer B, Laliotou B, et al. Effects of mycophenolate mofetil on nasal mucosal tolerance induction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1998; 39 (5): 835–40

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salzmann, J., Lightman, S. The Potential of Newer Immunomodulating Drugs in the Treatment of Uveitis. BioDrugs 13, 397–408 (2000). https://doi.org/10.2165/00063030-200013060-00003

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00063030-200013060-00003