Abstract

New weapons are needed in the fight against tuberculosis, both antibacterial drugs and a vaccine. If one new antituberculosis drug is developed it will encounter emerging resistance; at least two are needed, to be used in combination only. This is a complicated and difficult goal. In contrast, an effective new vaccine would have multiple antigenic targets within the bacterium, making the emergence of resistance to the vaccine unlikely. This is a simpler goal to achieve, and recent research indicates that it may be within reach.

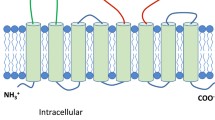

A diverse range of protein antigens can give encouragingly high levels of protective immunity in animal models when administered with adjuvants or as DNA vaccines. Accelerated arrest of bacterial multiplication, followed by sustained decline in bacterial numbers, are key parameters of protection; the vaccine must target antigens produced by actively multiplying bacteria as well as growth-inhibited bacteria. Consistent with this, the protective antigens have been found among secreted and stress proteins (for example Ag85, ESAT-6, hsp65, hsp70). Species-specific antigens are not required, so these remain available for diagnostic tests. Adoptive transfer of protection from vaccinated or infected mice into naive mice by transfer of purified T cells and clones shows that protection is expressed by antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells that produce interferon-γ and lyse infected macrophages. These cells are produced in response to endogenous antigen. DNA vaccination appears to be superior to recombinant mycobacterial or viral vectors for this purpose.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dolin PJ, Raviglione MC, Kochi A. Global tuberculosis incidence and mortality during 1990–2000. Bull World Health Organ 1994; 72: 213–20

Collins FM. Antituberculous immunity —new solutions to an old problem. Rev Infect Dis 91; 13: 940-50

Abou-Zeid C, Smith I, Grange JM, et al. The secreted antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and their relationship to those recognized by the available antibodies. J Gen Microbiol 1988; 134: 531–8

Andersen P, Askgaard D, Ljungqvist L, et al. Proteins released from Mycobacterium tuberculosis during growth. Infect Immun 1991; 59: 1905–10

Orme IM, Andersen P, Boom WH. T-cell response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 1993; 167: 1481–97

Young DB, Kaufmann SHE, Hermans PWM, et al. Mycobacterial protein antigens — a compilation. Mol Microbiol 92; 6: 133-45

Pal PG, Horwitz MA. Immunization with extracellular proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces cell-mediated immune responses and substantial protective immunity in a guinea pig model of pulmonary tuberculosis. Infect Immun 1992; 60: 4781–92

Lowrie DB, Silva CL, Colston MJ, et al. Protection against tuberculosis by a plasmid DNA vaccine. Vaccine 1997; 15: 834–6

Huygen K, Content J, Denis O, et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a tuberculosis DNA vaccine. Nat Med 1996; 2: 893–8

Balasubramanian V, Wiegeshaus EH, Smith DW. Mycobacterial infection in guinea pigs. Immunobiology 1994; 191: 395–401

Wiegeshaus EH, Harding G, McMurray D, et al. Aco-operative evaluation of test systems used to assay tuberculosis vaccines. Bull World Health Organ 1971; 45: 543–50

Lecoeur H, Lagrange PH, Truffot C, et al. Microbial persistence and tuberculosis hypersensitivity after chemotherapy of the mouse experimental tuberculosis. Ann Immun 1981; 132D: 237–48

de Wit D, Wootton M, Dhillon J, et al. The bacterial DNA content of mouse organs in the Cornell model of dormant tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis 1995; 76: 555–62

Walsh GP, Tan EV, de la Cruz EC, et al. The Philippine cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) provides a new non-human primate model of tuberculosis that resembles human disease. Nat Med 1996; 2: 430–6

Dannenberg AM, Sugimoto M. Liquefaction of caseous foci in tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1976; 113: 257–9

Converse PJ, Dannenberg AM, Estep JE, et al. Cavitary tuberculosis produced in rabbits by aerosolized virulent tubercle bacilli. Infect Immun 1996; 64: 4776–87

D’Arcy Hart P, Sutherland I. BCG and vole bacillus vaccines in the prevention of tuberculosis in adolescence and early adult life: final report to the Medical Research Council. BMJ 1977; 2: 293–5

Springett VH, Sutherland I. BCG vaccination of schoolchildren in England and Wales. Thorax 1990; 45: 83–8

Rodrigues LC, Diwan VK, Wheeler JG. Protective effect of BCG against tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis: a meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 1993; 22: 1154–8

Colditz GA, Berkey CS, Mosteller F, et al. The efficacy of bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination of newborns and infants in the prevention of tuberculosis: meta-analyses of the published literature. Pediatrics 1995; 96: 29–35

Smith PG. BCG vaccination. In: Davies PDO, editor. Clinical tuberculosis. London: Chapman and Hall, 1994: 297–310

Bloom BR, Fine PEM. The BCG experience: implications for future vaccines against tuberculosis. In: Bloom BR, editor. Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, protection, and control. Washington (DC): American Society for Microbiology, 1994: 531–57

Fine PEM. Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccines: a rough guide. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 20: 11–4

Comstock GW. Field trials of tuberculosis vaccines: how could we have done them better? Controlled Clin Trials 1994; 15: 247–76

Stanford JL, Rook GAW. Environmental mycobacteria and immunization with BCG. In: Easmon CSF, Jeljaszewicz J, editors. Medical microbiology volume 2: immunization against bacterial disease. London: Academic Press, 1983: 43–69

Palmer CE, Long MW. Effects of infection with atypical mycobacteria on BCG vaccination and tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1966; 94: 553–68

Edwards KL, Goodrich JM, Muller D, et al. Infection with Mycobacterium avium intracellulare and the protective effects of Bacille Calmette-Guerin. J Infect Dis 1982; 145: 733–41

Orme IM, Collins FM. Efficacy of Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination in mice undergoing prior pulmonary infection with atypical mycobacteria. Infect Immun 1984; 44: 28–32

Herbert D, Paramasivan CN, Prabhakar R. Protective response in guinea-pigs exposed to Mycobacterium avium intracellulare, M. scrofulaceum, BCG and South Indian isolates of M. tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res 1994; 99: 1–7

Kamala T, Paramasivan CN, Herbert D, et al. Immune response and modulation of immune response induced in the guinea-pigs by Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) and M. fortuitum complex isolates from different sources in the South Indian BCG trial area. Indian J Med Res 1996; 103: 201–11

Cheng SH, Walker KB, Lowrie DB, et al. Monocyte anti-mycobacterial activity before and after Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination in Chingleput, India, and London, United Kingdom. Infect Immun 1993; 61: 4501–3

Jacobs WR, Tuckman M, Bloom BR. Introduction of foreign DNA into mycobacteria using a shuttle plasmid. Nature 1987; 327: 532–5

Raz E, Tighe H, Sato Y, et al. Preferential induction of a Th-1 immune response and inhibition of specific IgE antibody formation by plasmid DNA immunization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93: 5141–5

Rook GAW, Hernandezpando R. T cell helper types and endocrines in the regulation of tissue-damaging mechanisms in tuberculosis. Immunobiology 1994; 191: 478–92

Stanford JL, Stanford CA. Immunotherapy of tuberculosis with Mycobacterium vaccae NCTC 11659. Immunobiology 1994; 191: 555–63

Onyebujoh PC, Abdulmumini T, Robinson S, et al. Immunotherapy with Mycobacterium vaccae as an addition to chemotherapy for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis under difficult conditions in Africa. Respir Med 1995; 89: 199–207

Cirillo JD, Stover CK, Bloom BR, et al. Bacterial vaccine vectors and Bacillus Calmette-Guerin. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 20: 1001–9

Collins FM. The immune response to mycobacterial infection: development of new vaccines. Vet Microbiol 1994; 40: 95–110

Lagrange PH. Cell-mediated immunity and delayed-type hypersensitivity. In: Kubica GP, Wayne LG, editors. The mycobacteria: a sourcebook. New York: Marcel Dekker,Inc., 1984; 681–720

Reiner NE. Altered cell signaling and mononuclear phagocyte deactivation during intracellular infection. Immunol Today 1994; 15: 374–81

Kaye PM. Costimulation and the regulation of antimicrobial immunity. Immunol Today 1995; 16: 423–7

Maes HH, Causse JE, Maes RE. Mycobacterial infections: are the observed enigmas and paradoxes explained by immunosuppression and immunodeficiency? Med Hypotheses 1996; 46: 163–71

Matsuo K, Yamaguchi R, Yamazaki A, et al. Establishment of a foreign antigen secretion system in mycobacteria. Infect Immun 1990; 58: 4049–54

Honda M, Matsuo K, Nakasone T, et al. Protective immune responses induced by secretion of a chimeric soluble protein from a recombinant Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin vector candidate vaccine for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in small animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92: 10693–7

Matsumoto S, Tamaki M, Yukitake H, et al. A stable Escherichia coli-mycobacteria shuttle vector pSO246 in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1996; 135: 237–43

Kong DQ, Kunimoto DY. Secretion of human interleukin 2 by recombinant Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect Immun 1995; 63: 799–803

Norman E, Dellagostin OA, McFadden J, et al. Gene replacement by homologous recombination in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Mol Microbiol 1995; 16: 755–60

Kameoka M, Nishino Y, Matsuo K. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte response in mice induced by a recombinant BCG vaccination which produces an extracellular alpha antigen that fused with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope immunodominant domain in the V3 loop. Vaccine 1994; 12: 153–8

Langermann S, Palaszynski SR, Burlein JE, et al. Protective humoral response against pneumococcal infection in mice elicited by recombinant Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccines expressing pneumococcal surface protein A. J Exp Med 1994; 180: 2277–86

Wada N, Ohara N, Kameoka M, et al. Long-lasting immune response induced by recombinant Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) secretion system. Scand J Immunol 1996; 43: 202–9

Falcone V, Bassey E, Jacobs W, et al. The immunogenicity of recombinant Mycobacterium smegmatis bearing BCG genes. Microbiology 1995; 141: 1239–45

Baumgart KW, McKenzie KR, Radford AJ, et al. Immunogenicity and protection studies with recombinant mycobacteria and vaccinia vectors coexpressing the 18-kilodalton protein of Mycobacterium leprae. Infect Immun 1996; 64: 2274–81

Mahairas GG, Sabo PJ, Hickey MJ, et al. Molecular analysis of genetic differences between Mycobacterium bovis BCG and virulent M. bovis. J Bacteriol 1996; 178: 1274–82

Harboe M, Oettinger T, Wiker HG, et al. Evidence for occurrence of the ESAT-6 protein in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and virulent Mycobacterium bovis and for its absence in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect Immun 1996; 64: 16–22

Brewer TF, Colditz GA. Relationship between bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) strains and the efficacy of BCG vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 20: 126–35

Sula L, Radkovsky J. Protective effects of M. microti vaccine against tuberculosis. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol 1976; 20: 1–6

Lyons J, Sinos C, Destree A, et al. Expression of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae proteins by vaccinia virus. Infect Immun 1990; 58: 4089–98

Symons JA, Alcami A, Smith GL. Vaccinia virus encodes a soluble type I interferon receptor of novel structure and broad species specificity. Cell 1995; 81: 551–60

Smith GL. Vaccinia virus glycoproteins and immune evasion. The sixteenth Fleming Lecture. J Gen Virol 1993; 74: 1725–40

Thole JER, Keulen WJ, et al. Characterisation, sequence determination, and immunogenicity of a 64-kilodalton protein of Mycobacterium bovis BCG expressed in Escherichia coli K-12. Infect Immun 1987; 55: 1466–75

Wiegeshaus EH, Smith DW. Evaluation of the protective potency of new tuberculosis vaccines. Rev Infect Dis 1989; 11: S484–90

Guile H, Fray LM, Gormley EP, et al. Responses of bovine T cells to fractionated lysate and culture filtrate proteins of Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 1995; 48: 183–90

Fifis T, Costopoulos C, Radford AJ, et al. Purification and characterization of major antigens from a Mycobacterium bovis culture filtrate. Infect Immun 1991; 59: 800–7

Wiker HG, Nagai S, Harboe M, et al. A family of cross-reacting proteins secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol 1992; 36: 307–19

Nagai S, Wiker HG, Harboe M, et al. Isolation and partial characterization of major protein antigens in the culture fluid of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun 1991; 59: 372–82

Andersen P, Askgaard D, Ljungqvist L, et al. T-cell proliferative response to antigens secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun 91; 59: 1558–63

Collins FM, Lamb JR, Young DB. Biological activity of protein antigens isolated from Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture filtrate. Infect Immun 1988; 56: 1260–6

Boesen H, Jensen BN, Wilcke T, et al. Human T-cell responses to secreted antigen fractions of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun 1995; 63: 1491–7

Lee BY, Horwitz MA. Identification of macrophage and stress-induced proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Invest 1995; 96: 245–9

Monahan IM, Banerjee DK, Jacobs WR, et al. Gene expression of Mycobacterium bovis BCG during interaction with macrophages. Third International Conference on the Pathogenesis of Mycobacterial Diseases; 1996 June 27–30: Stockholm, Sweden, 1996: 43

Andersen P. Effective vaccination of mice against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection with a soluble mixture of secreted mycobacterial proteins. Infect Immun 1994; 62: 2536–44

Horwitz MA, Lee BWE, Dillon BJ, et al. Protective immunity against tuberculosis induced by vaccination with major extracellular proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92: 1530–4

Andersen P. The T cell response to secreted antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunobiology 1994; 191: 537–47

Sorensen AL, Nagai S, Houen G, et al. Purification and characterization of a low-molecular-mass T-cell antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun 1995; 63: 1710–7

Andersen P, Andersen AB, Sorensen AL, et al. Recall of long-lived immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. J Immunol 1995; 154: 3359–72

Haslov K, Andersen A, Nagai S, et al. Guinea pig cellular immune responses to proteins secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun 1995; 63: 804–10

Roche PW, Triccas JA, Avery DT, et al. Differential T cell responses to mycobacteria-secreted proteins distinguish vaccination with bacille Calmette-Guerin from infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 1994; 170: 1326–30

Havlir DV, Wallis RS, Boom WH, et al. Human immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens. Infect Immun 91; 59: 665-70

Oftung F, Mustafa AS, Husson R, et al. Human T cell clones recognise two abundant Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein antigens expressed in Escherichia coli. J Immunol 1987; 138: 927–31

Barnes PF, Mehra V, Rivoire B, et al. Immunoreactivity of a 10-KdA antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol 92; 148: 1835–40

Mehra V, Bloom BR, Bajardi AC, et al. A major T-cell antigen of Mycobacterium leprae is a 10-kD heat-shock cognate protein. J Exp Med 92; 175: 275–84

Mendezsamperio P, Gonzalezgarcia L, Pinedafragoso PR, et al. Specificity of T cells in human resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Cell Immunol 1995; 162: 194–201

Lee BY, Hefta SA, Brennan PJ. Characterization of the major membrane protein of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun 92; 60: 2066-74

Young RA. Stress proteins and immunology. Annu Rev Immunol 1990; 8: 401–20

Kaufmann SHE. Heat shock proteins and the immune response. Immunol Today 1990; 11: 129–36

Mehra V, Gong JH, Iyer D, et al. Immune response to recombinant mycobacterial proteins in patients with tuberculosis infection and disease. J Infect Dis 1996; 174: 431–4

Yuan Y, Crane DD, Barry CE. Stationary phase-associated protein expression in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: function of the mycobacterial alpha-crystallin homolog. J Bacteriol 1996; 178: 4484–92

Tantimavanich S, Nagai S, Nomaguchi H, et al. Immunological properties of ribosomal proteins from Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect Immun 1993; 61: 4005–7

Youmans AS, Youmans GP. Immunogenic activity of a ribosomal fraction obtained from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol 1965; 89: 1291–8

Silva CL, Lowrie DB. A single mycobacterial protein (hsp65) expressed by a transgenic antigen-presenting cell vaccinates mice against tuberculosis. Immunology 1994; 82: 244–8

Tascon RE, Colston MJ, Ragno S, et al. Vaccination against tuberculosis by DNA injection. Nat Med 1996; 2: 888–92

Silva CL, Silva MF, Pietro RCLR, et al. Characterization of T cells that confer a high degree of protective immunity against tuberculosis in mice after vaccination with tumor cells expressing mycobacterial hsp65. Infect Immun 1996; 64: 2400–7

Young RA, Elliott TJ. Stress proteins, infection, and immune surveillance. Cell 1989; 59: 5–8

Nomoto K, Yoshikai Y. Heat-shock proteins and immunopathology —regulatory role of heat-shock protein-specific T-cells. Springer Semin Immunopathol 1991; 13: 63–80

Dicesare S, Poccia F, Mastino A, et al. Surface expressed heat-shock proteins by stressed or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected lymphoid cells represent the target for antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Immunology 1992; 76: 341–3

Murray PJ, Young RA. Stress and immunological recognition in host-pathogen interactions. J Bacteriol 1992; 174: 4193–6

Denagel DC, Pierce SK. Heat shock proteins in immune responses. Crit Rev Immunol 1993; 13: 71–81

Silva CL, Silva MF, Pietro RCLR, et al. Protection against tuberculosis by passive transfer with T-cell clones recognizing mycobacterial heat-shock protein 65. Immunology 1994; 83: 341–6

Silva CL, Pietro RLR, Januario A, et al. Protection against tuberculosis by bone marrow cells expressing mycobacterial hsp65. Immunology 1995; 86: 519–24

Orme IM. The kinetics of emergence and loss of mediator T lymphocytes acquired in response to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol 1987; 138: 293–8

Flynn JAL, Goldstein MM, Triebold KJ, et al. Major histocompatibility complex class I restricted T cells are necessary for protection against M. tuberculosis in mice. Infect Agent Dis 1993; 2: 259–62

Kaufmann SHE, Flesch IEA, Munk ME, et al. Cell-mediated immunity to mycobacteria — a double-sided sword. Rheumatol Int 1989; 9: 181–6

Cooper AM, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, et al. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gama gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med 1993; 178: 2243–7

Flynn JL, Chan J, Triebold KJ, et al. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med 1993; 178: 2249–54

Gupta LK, Bhatnagar S, Ram GC, et al. Role of cytotoxic lymphocytes in immunity against bovine tuberculosis. Med Sci Res 1995; 23: 535–8

Kaufmann SHE. Immunity to intracellular bacteria. Annu Rev Immunol 1993; 11: 129–63

Flynn JL, Goldstein MM, Triebold KJ, et al. Major histocompatibility complex class-I-restricted T-cells are required for resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992; 89: 12013–7

Tsukaguchi K, Balaji KN, Boom WH.. CD4(+) alpha beta T cell and gamma delta T cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis —similarities and differences in Ag recognition, cytotoxic effector function, and cytokine production. J Immunol 1995; 154: 1786–96

Boom WH. The role of T-cell subsets in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect Agents Disease Rev Issues Comment 1996; 5: 73–81

Wofffe JA, Ludtke JJ, Acsadi G, et al. Long-term persistence of plasmid DNA and foreign gene expression in mouse muscle. Hum Mol Genet 1992; 1: 363–9

Lefford MJ, McGregor DD. Immunological memory in tuberculosis. I. Influence of persisting viable organisms. Cell Immunol 1974; 14: 417–28

Griffin JP, Orme IM. Evolution of CD4 T-cell subsets following infection of naive and memory immune mice with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun 1994; 62: 1683–90

Sander B, Skansen Saphir U, Damm O, et al. Sequential production of Th1 and Th2 cytokines in response to live bacillus Calmette-Guerin. Immunology 1995; 86: 512–8

Yamamura M, Wang XH, Ohmen JD, et al. Cytokine patterns of immunologically mediated tissue damage. J Immunol 1992; 149: 1470–5

HernandezPando R, Orozcoe H, Sampieri A, et al. Correlation between the kinetics of Th1/Th2 cells and pathology in a murine model of experimental pulmonary tuberculosis. Immunology 1996; 89: 26–33

Rook GAW, Onyebujoh P, Stanford JL. TH1/TH2 switching and loss of CD4+ T-cells in chronic infections — an immunoendocrinological hypothesis not exclusive to HIV. Immunol Today 1993; 14: 568–9

Seder RA, Paul WE. Acquisition of lymphokine-producing phenotype by CD4+ T cells. Annu Rev Immunol 1994; 12: 635–73

Croft M, Carter L, Swain SL, et al. Generation of polarized antigen-specific CD8 effector populations: reciprocal action of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-12 in promoting type 2 versus type 1 cytokine profiles. J Exp Med 1994; 180: 1715–28

Kamala T, Paramasivan CN, Herbert D, et al. Isolation and identification of environmental mycobacteria in the Mycobacterium bovis BCG trial area of South India. Appl Environ Microbiol 1994; 60: 2180–3

Hernandez Pando R, Pavon L, Arriaga K, et al. Pathogenesis of tuberculosis in mice exposed to low and high doses of an environmental mycobacterial saprophyte before infection. Infect Immunol 1997; 65: 3317

Johnston SA, Tang DC. Gene gun transfection of animal cells and genetic immunization. Methods Cell Biol 1994; 43: 353–65

Haynes JR, Fuller DH, Eisenbraun MD, et al. Accell® particle-mediated DNA immunization elicits humoral, cytotoxic, and protective immune responses. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir 1994; 10: S43–55

Davis HL, Michel ML, Mancini M, et al. Direct gene transfer in skeletal muscle: plasmid DNA-based immunization against the hepatitis B virus surface antigen. Vaccine 1994; 12: 1503–9

Babiuk LA, Lewis PJ, Cox G, et al. DNA immunization with bovine herpesvirus-1 genes. Ann NY Acad Sci 1995; 772: 47–63

Hassett DE, Whitton JL. DNA immunization. Trends Microbiol 1996; 4: 307–12

Kumar V, Sercarz E. Genetic vaccination: the advantages of going naked. Nat Med 1996; 2: 857

Siegrist CA, Lambert PH. DNA vaccines: what can we expect? Infect Agents Dis Rev Issues Comment 1996; 5: 55–9

Robertson JS. The potential of DNA vaccines. J Biotechnol Healthcare 1996; 3: 239–47

Krieg AM. An innate immune defense mechanism based on the recognition of CpG motifs in microbial DNA. J Lab Clin Med 1996; 128: 128–33

Halpern MD, Kurlander RJ, Pisetsky DS. Bacterial DNA induces murine interferon-gamma production by stimulation of interleukin-12 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Cell Immunol 1996; 167: 72–8

Haslov K, Andersen AB, Ljungqvist L, et al. Comparison of the immunological activity of 5 defined antigens from Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 7 inbred guinea pig strains. Scand J Immunol 1990; 31: 503–14

Zhu X, Venkataprasad N, Thangaraj H, et al. Nucleic acid vaccination for protection against M. tuberculosis. Third International Conference on the Pathogenesis of Mycobacterial Infections; 1996 Jun 27–30: Stockholm, Sweden, 1996: 25

Andersen AB. Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins —structure, function, and immunological relevance. Dan Med Bull 1994; 41: 205–15

Andersen AB, Brennan P. Proteins and antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In: Bloom BR, editor. Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, protection, and control. Washington DC: American Society for Microbiology, 1994: 307–32

Russell WR, Pollock JM, Butcher PD, et al. The detection of M. bovis antigens expressed inside macrophages. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Mycobacterium bovis entitled ‘Tuberculosis in wildlife and domestic animals’; Dunedin: University of Otago Press, 1996: 135–8

Lim EM, Rauzier J, Timm J, et al. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA sequences encoding exported proteins by using phoA gene fusions. J Bacteriol 1995; 177: 59–65

Barry MA, Lai WC, Johnston SA. Protection against mycoplasma infection using expression-library immunization. Nature 1995; 377: 632–5

Cole ST. Why sequence the genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis? Tuber Lung Dis 1996; 77: 486–90

Anderton SM, van der Zee R, Noordzij A, et al. Differential mycobacterial 65-kDa heat shock protein T cell epitope recognition after adjuvant arthritis-inducing or protective immunization protocols. J Immunol 1994; 152: 3656–64

van Eden W, Anderton SM, van der Zee R, et al. Specific immunity as a critical factor in the control of autoimmune arthritis: the example of hsp60 as an ancillary and protective autoantigen. Scand J Rheumatol 1995; 101: 141–5

Prakken ABJ, van Eden W, Rijkers GT, et al. Autoreactivity to human heat-shock protein 60 predicts disease remission in oligoarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1996; 39: 1826–32

Billingham MEJ, Carney S, Butler R, et al. A mycobacterial 65-kD heat shock protein induces antigen-specific suppression of adjuvant arthritis, but is not itself arthritogenic. J Exp Med 90; 171: 339-44

Cohen IR. Autoimmunity to chaperonins in the pathogenesis of arthritis and diabetes. Annu Rev Immunol 1991; 9: 567–89

Cohen IR, Elias D. Immunity to 60 kDa heat shock protein in autoimmune diabetes. Diabetes Nutr Metab 1996; 9: 229–32

Anderton SM, Van Eden W. T-lymphocyte recognition of hsp 60 in experimental arthritis. In: Van Eden W, Young DB, editors. Stress proteins in medicine. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc., 1996: 73–91

Kingston AE, Hicks CA, Colston MJ, et al. A71-kD heat shock protein (hsp) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis has modulatory effects on experimental rat arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol 1996; 103: 77–82

Birk OS, Douek DC, Elias D, et al. A role of Hsp60 in autoimmune diabetes: analysis in a transgenic model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93: 1032–7

Adams E, Basten A, Rodda S, et al. Human T-cell clones to the 70-kilodalton heat shock protein of Mycobacterium leprae define mycobacterium-specific epitopes rather than shared epitopes. Infect Immun 1997; 65: 1061–70

Ragno S, Colston MJ, Lowrie DB, et al. Protection of rats from adjuvant arthritis by immunization with naked DNA encoding for mycobacterial heat shock protein 65. Arthritis Rheum 1997; 40: 277–83

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lowrie, D.B., Silva, C.L. & Tascon, R.E. Progress Towards a New Tuberculosis Vaccine. BioDrugs 10, 201–213 (1998). https://doi.org/10.2165/00063030-199810030-00004

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00063030-199810030-00004