Abstract

Background: Pioglitazone has been approved in Europe for oral combination therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Along with other agents of the thiazolidinedione class, it has a novel intracellular mechanism of action. Clinical trials with pioglitazone have confirmed a strong product profile in terms of control of blood glucose and lipids. However, the drug acquisition cost for pioglitazone is greater than standard medications for type 2 diabetes. Long-term data regarding the cost effectiveness of pioglitazone-based combination therapy are not available.

Objective: To evaluate, using a decision analysis model, the cost effectiveness of pioglitazone-based combination therapy compared with relevant alternative medications for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in Germany.

Methods: This study compared the clinical effects and costs of pioglitazone 30mg added to metformin in patients who failed metformin monotherapy and pioglitazone added to a sulphonylurea in patients who failed sulphonylurea monotherapy, with the most relevant treatment alternatives. A published and validated Markov model was adapted to reflect the management of type 2 diabetes. This simulated the number of severe complications occurring and the mean life expectancy of a diabetic cohort, which was based on the overweight group of the UK Prospective Diabetes Study at year 6 of follow-up. Drug treatment costs, other costs for general management of type 2 diabetes and the costs of complications were combined to compute overall lifetime treatment costs from the perspective of the German statutory healthcare system in 2002.

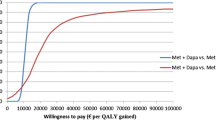

Results: Combination therapy with pioglitazone/metformin was associated with a higher life expectancy (15.2 years) relative to sulphonylurea/metformin (14.9 years) or acarbose/metformin (14.7 years). Likewise, pioglitazone/sulphonylurea (15.5 years) was superior to metformin/sulphonylurea (14.9 years) and acarbose/sulphonylurea (14.8 years). Undiscounted incremental cost-effectiveness ratios in comparison to the next best strategy were €20 002 per life-year gained (LYG) for pioglitazone/metformin versus sulphonylurea/metformin, and €8707 per LYG for pioglitazone/sulphonylurea versus metformin/sulphonylurea. After discounting costs and life expectancy at 5% per year, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was €47 636 per LYG for pioglitazone/metformin versus sulphonylurea/metformin, and €19 745 per LYG for pioglitazone/sulphonylurea versus metformin/ sulphonylurea.

Conclusions: In this model, with its underlying assumptions and data, combination therapy with pioglitazone increased life expectancy in overweight type 2 diabetes patients at acceptable cost compared with other well established medications in Germany. These findings should be re-evaluated as soon as additional evidence becomes available from the currently ongoing long-term clinical and economic studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The use of trade names is for product identification purposes only and does not imply endorsement.

Calculation method of HbA1c drift over time: cohort average HbA1C in year t = cohort HbA1C at baseline — treatment effect on HbA1C + (annual treatment-independent increase in HbA1C × t number of years). The annual treatmentindependent increase in HbA1C is 0.2 % in the second year after treatment start, and the HbA1C drift decreases continuously over time to 0.05 % after 10 years.

References

World Health Organization. Diabetes mellitus fact sheet no. 138. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002

Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type diabetes (UKPDS 34): UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet 1998; 352 (9131): 854–65

Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000; 321 (7258): 405–12

UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study 24: a 6-year, randomized, controlled trial comparing sulfonylurea, insulin, and metformin therapy in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes that could not be controlled with diet therapy. Ann Intern Med; 1998 Feb 1; 128 (3): 165–75

Koopmanschap M. Coping with type II diabetes: the patient’s perspective. Diabetologia 2002; 45 (7): S18–22

Gillies PS and Dunn CJ. Pioglitazone. Drugs 2000; 60 (2): 333–43

Kipnes MS, Krosnick A, Rendell MS, et al. Pioglitazone hydrochloride in combination with sulfonylurea therapy improves glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Med 2001; 111 (1): 10–7

Einhorn D, Rendell M, Rosenzweig J, et al. Pioglitazone hydrochloride in combination with metformin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, placebo-controlled study: the Pioglitazone 027 Study Group. Clin Ther 2000; 22 (12): 1395–409

Weinstein MC, O’Brien B, Hornberger J, et al. Principles of good practice for decision analytic modeling in health-care evaluation: report of the ISPOR Task Force on Good Research Practices - Modeling Studies. Value Health 2003; 6 (1): 9–17

Gozzoli V, Palmer Al, Brandt A, et al. Increased clinical and economic advantages using PROSIT (proteinuria screening and intervention) in type 2 diabetic patients. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2000; 125 (39): 1154–9

Gozzoli V, Palmer AJ, Brandt A, et al. Economic and clinical impact of alternative disease management strategies for secondary prevention in type 2 diabetes in the Swiss setting. Swiss Med Wkly 2001; 131 (21–22): 303–10

Palmer AJ, Weiss C, Sendi PP, et al. The cost-effectiveness of different management strategies for type I diabetes: a Swiss perspective. Diabetologia 2000; 43 (1): 13–26

Palmer Al, Weiss C, Brandt A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of intensive therapy for type 1 diabetes changes depending on risk factors and level of existing complications [abstract]. Med Decis Making 1997; 17 (4): 528

Hunt L. Pioglitazone the answer to managing type 2 DM in Europe? Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes News 2001; 343: 7–9

Brunetti P, Lucioni C, Schramm W. Terapia combinata con pioglitazone (Actos) net diabete di tipo 2 in Italia: valutazione farmacoeconomica. In: Pharmacoeconomic issues in type II diabetes. Milan: Adis International, 2002: 1–26

Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russel LB, et al. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996

Palmer Al, Neeser K, Paschen B, et al. Economic implications of the Total Ischaemic Burden Bisoprolol Study (TIBBS) follow-up. J Med Economics 1998; 1: 263–80

Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complica tions in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet 1998; 352 (9131): 837–53

Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. BMJ 1998; 317 (7160): 703–13

Efficacy of atenolol and captopril in reducing risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 39. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. BMJ 1998; 317 (7160): 713–20

UKPDS 28: a randomized trial of efficacy of early addition of metformin in sulfonylurea-treated type 2 diabetes. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Diabetes Care 1998; 21 (1): 87–92

Matthews DR, Cull CA, Stratton IM, et al. UKPDS 26: sulphonylurea failure in non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients over six years. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Diabet Med 1998; 15 (4): 297–303

Stevens RJ, Kothari V, Adler AI, et al. The UKPDS risk engine: a model for the risk of coronary heart disease in type II diabetes (UKPDS 56). Clin Sci (Lond) 2001; 101 (6): 671–9

Turner RC, Millns H, Neil HA, et al. Risk factors for coronary artery disease in non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS: 23). BMJ 1998; 316 (7134): 823–8

Turner RC, Cull CA, Frighi V, et al. Glycemic control with diet, sulfonylurea, metformin, or insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: progressive requirement for multiple thera pies (UKPDS 49). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. JAMA 1999; 281 (21): 2005–12

Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy. Heart Outcomes Preven tion Evaluation Study Investigators. Lancet 2000; 355 (9200): 253–9

Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, et al. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy: the Collaborative Study Group [published erratum appears in N Engl J Med 1993 Jan 13; 330 (2): 152]. N Engl J Med 1993; 329 (20): 1456–62

Assmann G, Schulte H, Cullen P. New and classical risk factors: the Munster Heart Study (PROCAM). Fur J Med Res 1997; 2 (6: 237–42)

Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BE. Long-term incidence of lowerextremity amputations in a diabetic population. Arch Fam Med 1996; 5 (7): 391–8

Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, et al. The Wisconsin Epidemiclogic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy. XV: the long-term incidence of macular edema. Ophthalmology 1995; 102 (1): 7–16

Kshirsagar AV, Joy MS, Hogan SL, et al. Effect of ACE inhibitors in diabetic and nondiabetic chronic renal disease: a systematic overview of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Am J Kidney Dis 2000; 35 (4): 695–707

Molyneaux LM, Constantino MI, McGill M, et al. Better glycaemic control and risk reduction of diabetic complications in type 2 diabetes: comparison with the DCCT. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1998; 42 (2): 77–83

The absence of a glycemic threshold for the development of long-term complications: the perspective of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes 1996; 45 (10): 1289–98

Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, et al. Probability of stroke: a risk profile from the Framingham Study. Stroke 1991; 22 (3): 312–8

Anderson KM, Odell PM, Wilson PW, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. Am Heart J 1991; 121 (1 Pt 2): 293–8

Neeser K, Weiss C, Weber C. Background information regarding the IMIB ‘TOM Diabetes’ disease model. Basel: Institute for Medical Informatics and Biostatistics (IMIB), 2003

NSW Health. MERGE - Method for Evaluating Research Guideline Evidence. State health publication no. (CEB) 96 - 204 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/public health [Accessed 2002 Feb 26]

U.K. prospective diabetes study 16. Overview of 6 years’ therapy of type II diabetes: a progressive disease. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Diabetes 1995; 44 (11): 1249–58

Piehlmeier W, Renner R, Schramm W, et al. Screening of diabetic patients for microalbuminuria in primary care: the PROSIT-Project. Proteinuria screening and intervention. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 1999; 107 (4): 244–51

National Cholesterol Education Program: second report of the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel II). Circulation 1994; 89 (3): 1333–445

Assmann G, Schulte H, von Eckardstein A. Hypertriglyceridemia and elevated lipoprotein(a) are risk factors for major coronary events in middle-aged men. Am J Cardiol 1996; 77 (14): 1179–84

Nakamura T, Ushiyama C, Osada S, et al. Pioglitazone reduces urinary podocyte excretion in type 2 diabetes patients with microalbuminuria. Metabolism 2001; 50 (10): 1193–6

Nakamura T, Ushiyama C, Shimada N, et al. Comparative effects of pioglitazone, glibenclamide, and voglibose on urinary endothelin-1 and albumin excretion in diabetes patients. J Diabetes Complications 2000; 14 (5): 250–4

Perez A, Cichy S, Glazer B. Progression of microalbuminuria during a long-term open-label (OL) trial of pioglitazone (PIO) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Abstract no. 450. Diabetes 2002; 51 Suppl. 2: AI11

Imano E, Kanda T, Nakatani Y, et al. Effect of troglitazone on microalbuminuria in patients with incipient diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care 1998; 21 (12): 2135–9

Isshiki K, Haneda M, Koya D, et al. Kidney disease and insulin resistance: clinical impact of thiazolidinedione compounds for kidney disease [in Japanese]. Nippon Rinsho 2000; 58 (2): 440–5

Isshiki K, Haneda M, Koya D, et al. Thiazolidinedione compounds ameliorate glomerular dysfunction independent of their insulin-sensitizing action in diabetic rats. Diabetes 2000; 49 (6: 1022–32

Miura Y, Kato Y, Yanamoto N, et al. Troglitazone improved diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes [abstract]. Diabetes 2000; 49: A19

Yoshimoto T, Naruse M, Nishikawa M, et al. Antihypertensive and vasculo- and renoprotective effects of pioglitazone in genetically obese diabetic rats. Am J Physiol 1997; 272 (6 Pt 1): E989–96

Day C. Thiazolidinediones: a new class of antidiabetic drugs. Diabet Med 1999; 16 (3): 179–92

Egan J, Rubin C, Mathisen A. Combination therapy with pioglitazone to metformin inpatients with type 2 diabetes [abstract]. Diabetes 1999; Suppl. 1; 48: A117

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the use of pioglitazone for type 2 diabetes mellitus: Technology Appraisal Guidance No 21 - March 2001. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2001

Egan J, Rubin C, Mathisen A. Adding pioglitazone to metformin therapy improves the lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes [abstract]. Diabetes 1999; Suppl. 1; 48: A106

Actos: prescribing information 2002. Indianapolis (IN): Eli Lilly, 2002

Rosskamp R. Safety aspects of oral hypoglycaemic agents. Diabetologia 1996; 39 (12): 1668–72

Schneider R, Egan J, Houser V. Combination therapy with pioglitazone and sulfonylurea in patients with type 2 diabetes [abstract]. Diabetes 1999; Suppl. 1; 48: A106

De Fronzo RA, Goodman AM. Efficacy of metformin in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: the multicenter metformin study group. N Engl J Med 1995; 333 (9): 541–9

Misbin RI, Green L, et al. Lactic acidosis in patients with diabetes treated with metformin. N Engl J Med 1998; 338 (4): 265–6

Hermann LS, Schersten B, Bitzen PO, et al. Therapeutic comparison of metformin and sulfonylurea, alone and in various combinations: a double-blind controlled study. Diabetes Care 1994; 17 (10): 1100–9

Chiasson JL, Josse RG, Hunt JA, et al. The efficacy of acarbose in the treatment of patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: a multicenter controlled clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1994; 121 (12): 928–35

Holman RR, Cull CA, Turner RC. A randomized double-blind trial of acarbose in type 2 diabetes shows improved glycemic control over 3 years (U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study 44). Diabetes Care 1999; 22 (6: 960–4

Mathisen A, Egan J, Schneider R. The effect of combination therapy with pioglitazone and sulfonylurea on the lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes [abstract]. Diabetes 1999; Suppl. 1; 48: A106

Costa B, Pinol C. Acarbose in ambulatory treatment of noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus associated to imminent sulfonylurea failure: a randomised-multicenric trial in primary health-care. Diabetes and Acarbose Research Group. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1997; 38 (1): 33–40

Todesursachenstatistik far das Jahr 1998: sterbefalle nach todesursachen in Deutschland 1999. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland, 1999

Johansen K. Efficacy of metformin in the treatment of NIDDM: meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 1999; 22 (1): 33–7

Schwabe U, Paffrath D. Arzneiverordnungs-report 2001. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2001

Köhler A, Hess R. K#x00F6;lner Kommentar zum EBM 2002. K#x00F6;ln: Demscher Arzte-Verlag, 2002

Wezel H, Liebold R. Handkommentar zum einheitlichen hewertungsmassstab für ärztliche leistungen (EBM) 2001. Sankt Augustin: Asgard-Verlag, 2001

Banz K, Dinkel R, Hanefeld M, et al. Evaluation of the potential clinical and economic effects of bodyweight stabilisation with acarbose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a decision analytical approach. Pharmacoeconomics 1998; 13 (4): 449–59

Statistisches Bundesamt. Gesundheitsbericht für Deutschland 1998 (7.8). Stuttgart: Metzler Poeschel, 1998: 410–13

Krankenhausdiagnosestatistik: diagnosedaten der krankenhauspatienten von 1997. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland, 1999

Laaser U, Breckenkamp J, Niermann U. Cost-effectivenessanalysis of medical interventions in patients with stroke in Germany under special consideration of ‘stroke units’. Gesundh ökon Qual Manag 1999; 4: 176–83

Dahmen HG. Diabetic foot syndrome and its risks: amputation, handicap, high-cost sequelae [in German]. Gesundheitswesen 1997; 59 (10): 566–8

Statistisches Bundesamt. Gesundheitsbericht far Deutschland 1998 (5.23). Stuttgart: Metzler Poeschel, 1998: 254–8

Schadlich PK, Brecht JG, Brunetti M, et al. Cost effectiveness of ramipril in patients with non-diabetic nephropathy and hypertension: economic evaluation of Ramipril Efficacy in Nephropathy (REIN) Study for Germany from the perspective of statutory health insurance. Pharmacoeconomics 2001; 19 (5 Pt 1): 497–512

Szucs TD, Smala AM, Fischer T. Costs of intensive insulin therapy in type 1 diabetes mellitus: experiences from the DCCT study [in German]. Fortschr Med 1998; 116 (31): 34–8

Statistisches Bundesamt. Gesundheitsbericht far Deutschland 1998 (6.13). Stuttgart: Metzler Poeschel, 1998: 341–5

Resource utilization and costs of care in the diabetes control and complications trial: the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Diabetes Care 1995; 18 (11): 1468–78

Rote liste 2003. Aulendorf Wartt: Editio Cantor Verlag für Medizin and Naturwissenschaften, 2003

Health expenditure for social security (OECD health data 1995–2000). Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2002

Tengs TO, Adams ME, Pliskin JS, et al. Five-hundred lifesaving interventions and their cost-effectiveness. Risk Anal 1995; 15 (3): 369–90

Kunz R, Oxman AD. The unpredictability paradox: review of empirical comparisons of randomised and non-randomised clinical trials. BMJ 1998; 317 (7167): 1185–90

German recommendations for health care economic evaluation studies. Revised version of the Hannover consensus: Hannover Consensus Group [in German]. Med Klin 2000; 95 (1): 52–5

Goldman L, Garber AM, Grover SA, et al. 27th Bethesda Conference: matching the intensity of risk factor management with the hazard for coronary disease events. Task Force 6: cost effectiveness of assessment and management of risk factors. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996; 27 (5): 1020–30

Liebl A, Neiss A, Spannheimer A, et al. Complications, comorbidity, and blood glucose control in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Germany: results from the CODE-2 study. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2002; 110 (1): 10–6

Turner RC. The U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study. A review. Diabetes Care 1998; 21 Suppl. 3: C35–38

Eastman RC, Javitt JC, Herman WH, et al. Model of complications of NIDDM. I: model construction and assumptions. Diabetes Care 1997; 20 (5): 725–34

Brown JB, Russell A, Chan W, et al. The global diabetes model: user friendly version 3.0. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2000; 50 Suppl. 3: S15–46

Brown JB, Palmer AJ, Bisgaard P, et al. The Mt. Hood challenge: cross-testing two diabetes simulation models. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2000; 50 Suppl. 3: S57–64

Coyle D, Palmer AJ, Tam R. Economic evaluation of pioglitazone hydrochloride in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Canada. Pharmacoeconomics 2002; 20 Suppl. 1: 31–42

Henriksson F. Applications of economic models in healthcare: the introduction of pioglitazone in Sweden. Pharmacoeconomics 2002; 20 Suppl. 1: 43–53

Robins JM. A new approach to causal inference in mortality studies with sustained exposure period: application to control of the healthy worker survivor effect. Mathematical Modelling 1986; 7: 1393–512

Cole SR, Heman MA. Fallibility in estimating direct effects. Int J Epidemiol 2002; 31 (1): 163–5

Heman MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Werler MM, et al. Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: an application to birth defects epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 155 (2): 176–84

Liao JK. Beyond lipid lowering: the role of statins in vascular protection 1. Int J Cardiol 2002; 86 (1): 5–18

Acknowledgements

Funding for the study was provided by Takeda Pharma (Aachen, Germany) to IMIB (Basel, Switzerland). The institutional authors had full and independent control over the contents of the manuscript. Dr Georg Lübben is an employee of Takeda Pharma (Aachen, Germany). Dr Uwe Siebert and his institutions did not receive any funding for this collaboration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neeser, K., Lübben, G., Siebert, U. et al. Cost Effectiveness of Combination Therapy with Pioglitazone for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus from a German Statutory Healthcare Perspective. PharmacoEconomics 22, 321–341 (2004). https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200422050-00006

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200422050-00006