Summary

Abstract

Escitalopram (Cipralex®), a new highly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), is the active S-enantiomer of RS-citalopram. It is effective in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and may have a faster onset of therapeutic effect than citalopram. It has also been shown to lead to improvements in measures of QOL. Escitalopram is generally well tolerated, with nausea being the most common adverse event associated with its use.

Modelled pharmacoeconomic analyses found escitalopram to have a costeffectiveness and cost-utility advantage over other SSRIs, including generic citalopram and fluoxetine and branded sertraline, and also over the serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine extended-release (XR). These studies used a decision-analytic approach with a 6-month time horizon and were performed in Western Europe (year of costing 2000 or 2001). Cost-effectiveness ratios for escitalopram, in terms of cost per successfully treated patient over 6 months, ranged from €871 to €2598 in different countries, based on direct costs and remission rates, and were consistently lower (i.e. more favourable) than the ratios for comparators (€970 to €3472). Outcomes similarly favoured escitalopram when indirect costs (represented by those associated with sick leave and loss of productivity) were included. The results of comparisons with citalopram, fluoxetine and sertraline were not markedly affected by changes to assumptions in sensitivity analyses, although comparisons with venlafaxine XR were sensitive to changes in the remission rate.

The mean number of QALYs gained during the 6-month period was similar for all drugs evaluated, but direct costs were lower with escitalopram, leading to lower cost-utility ratios than for comparators. Incremental analyses performed in two of the studies confirmed the cost-effectiveness and cost-utility advantage of escitalopram.

A prospective, 8-week comparative pharmacoeconomic analysis found that escitalopram achieved similar efficacy to venlafaxine XR, but was associated with 40% lower direct costs (€85 vs €142 per patient over 8 weeks; 2001 costs), although this difference did not reach statistical significance.

In both the modelled and prospective analyses, the differences in overall direct costs were mainly due to lower secondary care costs (in particular those related to hospitalisation) with escitalopram. In the prospective analysis, escitalopram had lower estimated drug acquisition costs than venlafaxine XR.

Conclusion: Escitalopram, the S-enantiomer of RS-citalopram and a highly selective SSRI, is an effective antidepressant in patients with MDD, has a favourable tolerability profile, and, on the basis of available data, appears to have a rapid onset of therapeutic effect. Modelled pharmacoeconomic analyses from Western Europe suggest that it may be a cost-effective alternative to generic citalopram, generic fluoxetine and sertraline. Although the available data are less conclusive in comparison with venlafaxine XR, escitalopram is at least as cost effective as the SNRI based on a prospective study, and potentially more cost effective based on modelled analyses. Overall, clinical and pharmacoeconomic data support the use of escitalopram as first-line therapy in patients with MDD.

Overview of Depression

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common condition with a lifetime prevalence of at least 5%. A chronic, recurrent illness, it is associated with significant disability, impaired health-related QOL and increased mortality, and is at least as debilitating as other chronic conditions such as diabetes mellitus and heart disease. However, it is often underdiagnosed and undertreated.

MDD imposes a significant economic burden on society. The total annual cost of depression in the UK was estimated to be £3.5 billion for 1990 (the most recent year for which this cost has been published). Most studies have shown that direct healthcare costs account for less than a third of the total costs associated with MDD. Within this, drugs account for only 2–11% of direct costs. Indirect costs account for the greater proportion of overall costs; they are harder to calculate, but in the UK have been estimated to be 7-fold greater than the direct costs of MDD.

Clinical Profile of Escitalopram in Depression

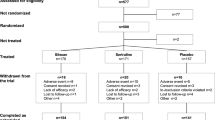

The antidepressant activity of escitalopram has been demonstrated in randomised, Escitalopram in double-blind comparative trials in patients with moderate to severe MDD. Depression Approximately half of these studies were reported as full papers and half as abstracts/posters.

Antidepressant activity was observed in patients treated with escitalopram 10–20 mg/day for 8 weeks, with significant improvements in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) scores compared with placebo being seen from as early as 1–2 weeks after starting treatment. At the end of 8 weeks, 49–64% of patients treated with escitalopram 10–20 mg/day had responded (≥50% decrease in MADRS score from baseline), compared with 28–48% of those receiving placebo (p < 0.05). Significant improvements were also seen for secondary efficacy parameters which included scores for the Clinical Global Impressions Improvement and Severity scales.

A meta-analysis found that, compared with placebo, escitalopram led to a statistically significant greater reduction in MADRS score (p < 0.01) from week 1, whereas it reached significance compared with placebo only at week 6 for citalopram.

MADRS scores continued to improve with longer-term (up to 1 year) treatment. After 36 weeks of treatment, escitalopram reduced the risk of relapse by 44% relative to placebo (p = 0.013).

Escitalopram 10–20 mg/day was at least as effective as citalopram 20–40 mg/day based on the preliminary results of a 24-week comparative study and a meta-analysis of studies of 8 weeks’ duration that included both escitalopram and citalopram arms. Response rates were 55.5% and 50.8% for escitalopram and citalopram in the latter analysis (p = 0.01), and escitalopram produced a significantly greater reduction in MADRS score from baseline than citalopram at week 1 (p = 0.02) as well as week 8 (p = 0.03). In one of the 8-week trials, time to response was 8.1 days faster with escitalopram than with citalopram (p < 0.05).

Escitalopram 10–20 mg/day had similar efficacy to venlafaxine extended-release (XR) 75–150 mg/day based on the preliminary results of an 8-week study. For those patients achieving response or remission, the mean times to response and remission were shorter with escitalopram by 4.6 (p < 0.05) and 6.6 days (p < 0.001). In a second study using fixed dosages, escitalopram 20 mg/day was as effective as venlafaxine 225 mg/day in the total patient population; in a subgroup of patients with severe MDD, escitalopram led to significantly greater reductions in MADRS scores than venlafaxine XR (p < 0.05).

Escitalopram was generally well tolerated in clinical trials, including during long-term treatment of up to 1 year, with most adverse events being mild and transient. The type of adverse events reported were similar to those recognised for citalopram. Nausea was the most common adverse event associated with escitalopram, occurring in >10% of patients. Other adverse events with a higher incidence than seen in placebo-treated patients included increased sweating, insomnia, somnolence, dizziness, diarrhoea, constipation, decreased appetite, fatigue and sexual dysfunction (all <10%).

Preliminary data from one trial suggested that escitalopram 10–20 mg/day may be associated with significantly less nausea, constipation and sweating (p = 0.02) and less marked discontinuation-emergent signs and symptoms (p < 0.01) than venlafaxine XR 75–150 mg/day.

Escitalopram 10–20 mg/day significantly improved social functioning and QOL compared with placebo, and produced similar improvements in QOL to those seen with venlafaxine XR 75–150 mg/day in patients with moderate to severe MDD.

Pharmacoeconomic Analyses of Escitalopram

One prospective pharmacoeconomic analysis has been performed comparing escitalopram with venlafaxine XR. Five modelled analyses have compared escitalopram with citalopram, fluoxetine, venlafaxine XR and (in one study) sertraline. All studies evaluated cost effectiveness and several included an assessment of cost utility. The modelled analyses also estimated the effect of escitalopram on overall healthcare budgets for the treatment of depression. All analyses were performed in Western Europe. All studies evaluated direct healthcare costs; several also assessed indirect costs, as represented by the costs of sick-leave and associated lost production.

The prospective pharmacoeconomic analysis was performed in parallel with a multinational clinical trial comparing escitalopram 10–20 mg/day with venlafaxine XR 75–150 mg/day. Both antidepressants improved MADRS scores and QOL measures to a similar extent during the 8-week study. Escitalopram was associated with 40% lower direct healthcare costs than venlafaxine XR €85 vs €142 per patient over 8 weeks; 2001 costs); however, this did not reach statistical significance. The difference in direct costs was largely due to fewer escitalopram than venlafaxine-recipients requiring hospitalisation (0 vs 4 patients) and lower drug acquisition costs with escitalopram. Multivariate analysis showed that, when adjusted to cost drivers at baseline, direct costs were significantly lower with escitalopram than venlafaxine XR (coefficient = -0.57, p = 0.03). Indirect costs per patient were similar for both groups (€680 for escitalopram and €689 for venlafaxine XR). There was no statistically significant difference between the two treatment groups in terms of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios based on direct costs and QOL outcomes.

The modelled pharmacoeconomic analyses were performed in Finland, Norway, Sweden, Belgium and the UK (year of costing 2000 or 2001). All used similar methodology, were based on a two-path decision analytic model with a 6-month time horizon, and evaluated cost effectiveness, cost utility (except the Norwegian study) and the potential effect of escitalopram on overall healthcare budgets for the treatment of depression.

In all of the modelled analyses, escitalopram was more cost effective from the healthcare provider perspective than generic citalopram, generic fluoxetine, venlafaxine XR and sertraline (assessed in the UK study only) in the treatment of MDD. Cost-effectiveness ratios based on direct healthcare costs per successfully-treated patient (MADRS score ≤12) over 6 months ranged from €871 to €2598. In each country the ratio was lower (i.e. more favourable) for escitalopram than for the comparators (range for comparators: €970–€3472). This was largely due to lower secondary care costs for escitalopram. Limitations of the analyses included a lack of direct comparative clinical trial data between escitalopram and most of the comparator agents. In the three studies in which indirect costs were evaluated, escitalopram was also more cost effective from the societal perspective. In general, the results were supported by sensitivity analyses, although the outcome against venlafaxine XR was sensitive to changes in the escitalopram remission rate at the lower boundary of probabilities tested.

Incremental analyses performed in the UK and Belgian studies confirmed the comparative cost-effectiveness advantage associated with escitalopram. In addition, although all of the evaluated drugs were considered to result in similar QALYs gained, escitalopram was associated with lower direct healthcare costs, resulting in a cost-utility advantage for escitalopram over the comparators for the 6-month study period.

Assuming a scenario in which only patients receiving branded citalopram are switched to escitalopram, the 2004 total healthcare budgets for the treatment of depression in Finland, Norway, Sweden and the UK were estimated to be reduced by 2.4–4.4%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Use of tradenames is for identification purposes only and does not imply endorsement.

References

Isaac M. Where are we going with SSRIs? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1999 Jul; 9 Suppl. 3: S101–6

Ballenger JC, Davidson JRT, Lecrubier Y, et al. Consensus statement on the primary care management of depression from the Internation Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60 Suppl. 7: 54–61

Baldwin DS. Unmet needs in the pharmacological management of depression. Hum Psychopharmacol 2001; 16 Suppl. 2: S93–9

MacGillivray S, Arroll B, Hatcher S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors compared with tricyclic antidepressants in depression treated in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2003 May 10; 326 (7397): 1014–7

Keller MB, Hirschfeld RMA, Demyttenaere K, et al. Optimizing outcomes in depression: focus on antidepressant compliance. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2002 Nov; 17 (6: 265–71

Le Pen C, Levy E, Ravily V, et al. The cost of treatment dropout in depression. A cost-benefit analysis of fluoxetine vs. tricyclics. J Affect Disord 1994 May; 31 (1): 1–18

Henry JA, Alexander CA, Setter EK. Relative mortality from overdose of antidepressants. BMJ 1995 Jan 28; 310 (6874): 221–4

Anderson IM, Tomenson BM. Treatment discontinuation with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors compared with tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis. BMJ 1995 Jun 3; 310 (6992): 1433–8

Eccles M, Freemantle N, Mason J. North of England evidencebased guideline development project: summary version of guidelines for the choice of antidepressants for depression in primary care. Fam Pract 1999 Apr; 16 (2): 103–11

Skaer TL, Sclar DA, Robison LM, et al. Trend in the use of antidepressant pharmacotherapy and diagnosis of depression in the US: an assessment of office-based visits 1990 to 1998. CNS Drugs 2000 Dec; 14 (6: 473–81

Keller MB. Citalopram therapy for depression: a review of 10 years of European experience and data from U.S. clinical trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2000 Dec; 61 (12): 896–908

H. Lundbeck A/S. Cipralex: summary of product characteristics [online]. Available from URL: http://www.cipralex.com [Accessed 2003 Jun 10]

Burke WJ. Escitalopram. Expert Opinion Investig Drugs 2002 Oct; 11 (10): 1477–86

Thase ME. Long-term nature of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60 Suppl. 14: 3–9

Hirschfield RMA. Clinical importance of long-term antidepressant treatment. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 179 Suppl. 42: S4–8

Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al. The functioning and wellbeing of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989 Aug 18; 262 (7): 914–9

Zheng D, Macera CA, Croft JB, et al. Major depression and allcause mortality among white adults in the United States. Ann Epidemiol 1997 Apr; 7 (3): 213–8

Doris A, Ebmeier K, Shajahan P. Depressive illness. Lancet 1999 Oct; 354 (9187): 1369–75

Bremner JD, Vythilingam M, Ng CK, et al. Regional brain metabolic correlates of alpha-methylparatyrosine-induced depressive symptoms: implication for the neural circuitry of depression. JAMA 2003 Jun 18; 289 (23): 3125–34

Nutt DJ. The neuropharmacology of serotonin and noradrenaline in depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2002 Jun; 17 Suppl. 1: S1–S12

Chamey DS. Monoamine dysfunction and the pathophysiology and treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59 Suppl. 14: 11–4

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comor-bidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003 Jun; 289 (23): 3095–105

Lépine J-P, Gastpar M, Mendlewicz J, et al. Depression in the community: the first pan-European study DEPRES (Depression Research in European Society). Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1997 Jan; 12 (1): 19–29

Angst J. Comorbidity of mood disorders: a longitudinal pro-spective study. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168 Suppl. 30: 31–7

Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA 1996; 276 (4): 293–9

Ayuso-Mateos JL, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Dowrick C, et al. Depressive disorders in Europe: prevalence figures from the ODIN study. Br J Psychiatry 2001 Oct; 179: 308–16

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12 month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994 Jan; 5 (1): 8–19

Ohayon MM, Priest RG, Guilleminault C, et al. The prevalence of depressive disorders in the United Kingdom. Biol Psychiatry 1999 Feb; 45 (3): 300–7

Peveler R, Carson A, Rodin G. Depression in medical patients. BMJ 2002 Jul 20; 325 (7356: 149–52

Angst J, Angst F, Stassen HH. Suicide risk in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60 Suppl. 2: 57–62

Penninx BWJH, Geerlings SW, Deeg DJH, et al. Minor and major depression and the risk of death in older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999 Oct; 56 (10): 889–95

Mody SH, Edell WS, Durkin MB, et al. The impact of depres-sion on health-related quality of life [abstract no. PMH27]. Value Health 2000; 3 (2): 87

Patrick D, LIDO Group. Quality of life correlates of major depression in six countries [abstract no. S-224-4 plus oral presentation]. 12th World Congress of Psychiatry; 2002 Aug 24; Yokohama, 219

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Linzer M, et al. Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders. Results from the PRIME-MD Study. JAMA 1995 Nov; 274 (19): 1511–7

Conti DJ, Burton WN. The cost of depression in the workplace. Behav Healthe Tomorrow 1995; 4 (4): 25–7

Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, et al. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA 1990 Nov 21; 264 (19): 2524–8

Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997 May; 349 (9064): 1498–504

World Health Organisation. The global burden of disease [online]. Available from URL: http://who.int/msa/mnh/ems/dalys/ table.htm [Accessed 2003 Jun 6]

Berio P, D’Ilario D, Ruffo P, et al. Depression: cost-of-illness studies in the international literature, a review. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2000 Mar 1; 3 (1): 3–10

Kind P, Sorensen J. The costs of depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1993 Jan; 7: 191–5

Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, et al. The economic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatry 1993 Nov; 54 (11): 405–18

Kiejna A, Czech M, Falma T, et al. Cost of the first, second and subsequent episode of depression in Poland [abstract]. Value Health 2001; 4 (6): 416

Jonsson B, Bebbington PE. What price depression? The cost of depression and the cost-effectiveness of pharmacological treatment. Br J Psychiatry 1994 May; 164 (5): 665–73

West R. Depression. London: Office of Health Economics, 1992

Henry JA, Rivas CA. Constraints on antidepressant prescribing and principles of cost-effective antidepressant use. Part 1: depression and its treatment. Pharmacoeconomics 1997 May; 11 (5): 419–43

Creed F, Morgan R, Fiddler M, et al. Depression and anxiety impair health-related quality of life and are associated with increased costs in general medical inpatients. Psychosomatics 2002; 43 (4): 302–9

Sheehan DV. Establishing the real cost of depression. Manag Care 2002 Aug; 11 (8 Suppl.): 7–10; discussion 21–5

Simon GE, Katzelnick DJ. Depression, use of medical services and cost-offset effects. J Psychosom Res 1997 Apr; 42 (4): 333–44

Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, Greist III, et al. Effect of primary care treatment of depression on service use by patients with high medical expenditures. Psychiatr Serv 1997 Jan; 48 (1): 59–64

Russell JM, Patterson J, Baker AM. Depression in the workplace: epidemiology, economics and effects of treatment. Dis Manag Health Outcomes 1998 Sep; 4 (3): 135–42

Stewart WIT, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al. Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA 2003 Jun; 289 (23): 3135–44

Hirschfeld RMA, Keller MB, Panico S, et al. The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 1997; 277 (4): 333–40

Donoghue J, Taylor DM. Suboptimal use of antidepressants in the treatment of depression. CNS Drugs 2000 May; 13 (5): 365–83

Davidson JRT, Meltzer-Brody SE. The underrecognition and undertreatment of depression: what is the breadth and depth of the problem? J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60 Suppl. 7: 4–9

Revicki DA, Simon GE, Chan K, et al. Depression, healthrelated quality of life, and medical cost outcomes of receiving recommended levels of antidepressant treatment. J Fam Pract 1998 Dec; 47 (6): 446–52

McCombs IS, Nichol MB, Stimmel GL. The role of SSRI antidepressants for treating depressed patients in the California Medicaid (Medi-Cal) Program. Value Health 1999; 2 (4): 269–80

Komstein SG, Schneider RK. Clinical features of treatmentresistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62 Suppl. 16: 18–25

Baker CB, Woods SW. Cost of treatment failure for major depression: direct costs of continued treatment. Adm Policy Ment Dec Health 2001 Mar; 28 (4): 263–77

Ozminkowski RJ, Russell JM, Crown WH, et al. The cost consequences of continued treatment-resistance in depression [abstract no. PMH23]. Value Health 2002; 5 (3): 235

Gilsenan AW, Hopkins IS, Sherrill BH, et al. Prevalence and costs of treatment-resistant depression in a Canadian claims database [abstract]. Value Health 2002; 5 (3): 231–2

Corey-Lisle P, Claxton A, Birnbaum H, et al. Identification and one-year costs of treatment-resistant depression in a claims data analysis [abstract]. Value Health 2001; 4 (6): 458

Crown WH, Finkelstein S, Berndt ER, et al. The impact of treatment-resistant depression on health care utilization and costs. J Clin Psychiatry 2002 Nov; 63 (11): 963–71

Waugh J, Goa K. Escitalopram: a review of its use in the management of major depressive and anxiety disorders. CNS Drugs 2003; 17 (5): 343–62

Burke WJ, Gergel I, Bose A. Fixed-dose trial of the single isomer SSRI escitalopram in depressed outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 2002 Apr; 63 (4): 331–6

Wade A, Lemming OM, Bang Hedegaard K. Escitalopram 10 mg/day is effective and well tolerated in a placebo-controlled study in depression in primary care. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2002 May; 17 (3): 95–102

Gorman JM, Korotzer A, Su G. Efficacy comparison of escitalopram and citalopram in the treatment of major depressive disorder: pooled analysis of placebo-controlled trials. CNS Spectrums 2002; 7 Suppl. 1: 40–4

Lepola UM, Loft H, Reines EH. Escitalopram (10–20 mg/day) is effective and well tolerated in a placebo-controlled study in depression in primary care. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2003 Jul; 18 (4): 211–7

Auquier P, Robitail S, Llorca P-M, et al. Comparison of escitalopram and citalopram efficacy: a meta-analysis. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. In press

Colonna L, Reines EH, Andersen HF. Escitalopram is well tolerated and more efficacious than citalopram in long-term treatment of moderately depressed patients [abstract]. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2002; 6 (4): 243–4 plus poster presented at the 3rd International Forum on Mood and Anxiety Disorders; 2003 Nov 27–30; Monte Carlo

Montgomery SA, Huusom AKT, Bothmer J. Escitalopram is a new and highly efficacious SSRI in the treatment of major depressive disorder [abstract no. P.1.206]. Fur Neuropsychopharmacol 2002; 12 Suppl. 3: S224

Ninan PT, Ventura, D, Wang, J. Escitalopram is effective and well-tolerated in the treatment of severe depression [abstract no. NR486 plus poster]. American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; 2003 May 17–23; San Francisco

Bielski R, Ventura D, Chang C, et al. Double-blind comparison of escitalopram and venlafaxine XR in the treatment of major depressive disorder [abstract no. P.1.207]. European Neuro psychopharmacol 2003; 13 Suppl. 4: S262 plus poster presented at the 16th Congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology; 2003 Sep 20–24; Prague

Wade A, Despiegel N, Reines E. Depression in primary care patients: improvement during long-term escitalopram treatment [abstract no. P.1.156]. Fur Neuropsychopharmacol 2002; 12 Suppl. 3: 232

Rapaport MIL, Bose A, Zheng H. Escitalopram prevents relapse of depressive episodes [abstract no. P01.12]. Fur Psychiatry 2002; 17 Suppl. 1: 97

Wade A, Despiegel N, Glesner LE. Depression in primary care patients: escitalopram is safe and well tolerated in long-term treatment [abstract no. P.3.E.035]. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2002 Jun; 5 Suppl. 1: S146 plus poster presented at the 23rd ECNP Congress; 2002 Oct 5–9; Barcelona

H. Lundbeck A/S. Data on file. Copenhagen, Paris: H. Lundbeck A/S,2003

Gergel I, Hakkarainen H, Zornberg G. Escitalopram is a well tolerated SSRI [abstract no. NR333]. American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; 2002 May 18–23; Philadelphia

Hirschfield RMA, Montgomery SA, Keller MB, et al. Social functioning in depression: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 2000 Apr; 61 (4): 268–75

Sapin C, Le Lay A, Llorca P-M, et al. Assessing health-related quality of life in clinical trials of patients with major depres-sive disorder [abstract plus poster]. 6th Annual European Con gress of the International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research; 2003 Nov 9–11; Barcelona

Fernandez J, Montgomery SA, Frangois C. Economic evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of escitalopram versus venlafaxine XR in major depressive disorder. Paris: Lundbeck A/S, 2003. (Data on file)

EuroQol Group. EQ-5D self-report questionnaire [online]. Available from URL: http://www.eurogol.org [Accessed 2003 Aug 7]

Frangois C, Sintonen H, Toumi M. Introduction of escitalopram, a new SSRI in Finland: comparison of cost-effectiveness between the other SSRIs and SNRI for the treatment of depres sion and estimation of the budgetary impact. J Med Econ 2002; 5: 91–107

Frangois C, Henriksson F, Toumi M, et al. A Swedish pharmacoeconomic evaluation of escitalopram, a new SSRI: comparison of cost-effectiveness between escitalopram, citalo pram, fluoxetine and venlafaxine [abstract]. Value Health 2002; 5 (3): 230 plus poster presented at the ISPOR Seventh Annual International Meeting; 2002 May 19–22; Arlington (VA)

Wade A, McCrone, P, Anderson I, et al. Cost-effectiveness of escitalopram, a new SSRI, in the treatment of major depressive disorder in the UK [abstract plus poster]. 1st Asia-Pacific Conference for Pharmacoeconomic and Outcomes Research; 2003 Sep 1–3; Kobe

Demyttenaere K, Rachidi S, Van Dijck P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of escitalopram compared to brand and generic SSRI (citalopram and fluoxetine), and venlafaxine in the treatment of depression in Belgium. Paris: Lundbeck A/S, 2003. (Data on file)

Montgomery SA, Fernandez JL, Frangois C. Treatment of depression: escitalopram has similar efficacy but lower costs compared to venlafaxine XR [abstract no. PMH42]. Value Health 2003; 6 (3): 358 plus poster presented at the ISPOR Eighth Annual Meeting; 2003 May 18–21; Arlington (VA)

Frangois C, Toumi M, Aakhus A-M, et al. A pharmacoeconomic evaluation of escitalopram, a new selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Fur J Health Econ 2003; 4: 12–9

Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depression (revision). American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry 2000 Apr; 157 (4 Suppl.): 1-45

Donoghue J, Hylan TR. Antidepressant use in clinical practice: efficacy v. effectiveness. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 179 Suppl. 42: S9–S17

Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, Deakin JFW. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 1993 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol 2000 Mar; 14 (1): 3–20

Robert P, Montgomery SA. Citalopram in doses of 20–60 mg is effective in depression relapse prevention: a placebo-controlled 6 month study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1995 Mar; 10 Suppl. 1: 29–35

Montgomery SA, Rasmussen JG, Tanghoj P. A 24-week study of 20 mg citalopram, 40 mg citalopram, and placebo in the prevention of relapse of major depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1993 Fall; 8 (3): 181–8

Entsuah AR, Rudolph RL, Hackett D, et al. Efficacy of venlafaxine and placebo during long-term treatment of depression: a pooled analysis of relapse rates. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1996 Jun; 11 (2): 137–45

Sapin C, Fantino B, Nowicki, M-L, et al. The value of healthrelated quality of life in primary care patients with major depressive disorder [abstract no. 1347]. 10th Annual Conference of the International Society for Quality of Life Research; 2003 Nov 12–15; Prague

Bank of England Monetary and Financial Statistics Division. Exchange rate data: annual average exchange rates 2001 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.bankofengland.co.uk [Accessed 2003 Sep 17]

Freeman H, Arikian S, Lenox-Smith A. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of antidepressants for major depressive disorder in the United Kingdom. Pharmacoeconomics 2000 Aug; 18 (2): 143–8

Doyle JJ, Casciano J, Arikian S, et al. A multinational pharmacoeconomic evaluation of acute major depressive disorder (MDD): a comparison of cost-effectiveness between venlafaxine, SSRIs and TCAs [abstract]. Value Health 2001; 4 (1): 16–31

Harlow SD, Linet MS. Agreement between questionnaire data and medical records: the evidence for accuracy of recall. J Epidemiol 1989 Feb; 129 (2): 233–48

Revicki DA, Irwin D, Reblando J, et al. The accuracy of selfreported disability days. Med Care 1994 Apr; 32 (4): 401–4

Kielhorn A, Graf von der Schulenburg J-M. The health economics handbook. 2nd ed. Chester: Adis International, 2000

Drummond MF, O’Brien BJ, Stoddart GL, et al. Collection and analysis of data. Modelling studies: approaches and issues. In: Drummond ME, O’Brien BJ, Stoddart GL, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997: 242–7

Simon G, Wagner E, Vonkorff M, et al. Cost-effectiveness comparisons using “real world” randomized trials: the case of new antidepressant drugs. J Clin Epidemiol 1995 Mar; 48 (3): 363–73

Henry JA, Rivas CA. Constraints on antidepressant prescribing and principles of cost-effective antidepressant use. Part 2: costeffectiveness analyses. Pharmacoeconomics 1997 Jun; 11 (6): 515–37

Frank L, Revicki DA, Sorensen SV, et al. The economics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in depression: a critical review. CNS Drugs 2001 Jan; 15 (1): 59–83

Williams JW, Mulrow CD, Chiquette E, et al. A systematic review of newer pharmacotherapies for depression in adults: evidence report summary. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132: 743–56

Panzarino Jr PJ, Nash DB. Cost-effective treatment of depression with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Am J Manag Care 2001 Feb; 7 (2): 173–84

Russell JM, Berndt ER, Miceli R, et al. Course and cost of treatment for depression with fluoxetine, paroxetine, and ser-traline. Am J Manag Care 1999 May; 5 (5): 597–606

Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. Dual-action Effexor XR, fastest growing antidepressant market [media release]. 2002 Sep 18

Keller MB. The long-term treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60 Suppl. 17: 41–5

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Croom, K.F., Plosker, G.L. Escitalopram. Pharmacoeconomic 21, 1185–1209 (2003). https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200321160-00004

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200321160-00004